Impact statement

As the global population continues to experience displacement due to conflict, disasters and other crises, addressing the mental health and psychosocial well-being of displaced communities in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) remains a critical and ongoing concern. This review has identified 15 high-quality studies on the key factors impacting the acceptability and accessibility of mental health and psychosocial programmes targeting displaced populations in LMICs, such as stigma, gender, language, literacy and the locational reach of services. The stigma surrounding mental health remains pervasive in many societies, impeding help-seeking behaviours and reinforcing a culture of shame around psychological health. Addressing stigma requires psychoeducative approaches that respect cultural beliefs and promote mental health awareness and acceptance. Similarly, acceptability of programme components can differ by gender; thus, an assessment of gender and other sociocultural factors could be assessed during feasibility phases of programme trials to inform whether any adjustments need to be made to ensure greater equity in participation. Consideration of language and literacy barriers is also crucial for ensuring access to all programme components and optimising engagement in MHPSS services. Furthermore, the physical location of the displaced populations can hinder programme accessibility. In remote or conflict-affected regions, access to mental health and psychosocial support services may be limited, and timing and competing demands may necessitate taking a pragmatic approach to programming. Overall, understanding which factors and delivery mechanisms contribute to the successful implementation of MHPSS programmes, prior to scale-up is crucial for ensuring they are inclusive and effective.

Introduction

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that, by the end of 2022, a total of 108.4 million people were forcibly displaced worldwide. This includes approximately ‘35.3 million refugees, 5.4 million asylum-seekers, 62.5 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 5.2 million other people in need of international protection’ (UNHCR, 2023). The majority of individuals and families are hosted in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly in regions such as Africa, the Middle East and South Asia. The impact of forced displacement on mental health can be significant and long-lasting (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Kvietok, Pauschardt, Freier and Bird2023). Displacement can result in a range of psychological distress symptoms, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems (Patanè et al., Reference Patanè, Ghane, Karyotaki, Cuijpers, Schoonmade, Tarsitani and Sijbrandij2022). This can be due to a variety of factors, including loss of a person’s home and community, exposure to violence and trauma, uncertainty about the future and limited access to basic needs such as food, shelter and healthcare (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Liu, Liang, Ho, Kim, Seong, Bonanno, Hobfoll and Hall2020). Such factors are often compounded due to the stress that displacement places on an individuals’ social support systems, leading to intensified feelings of isolation, loneliness and psychological distress (Miller and Rasmussen, Reference Miller and Rasmussen2017). Children and adolescents can face distinct challenges, such as prolonged separation from caregivers, risk of exploitation and abuse in unfamiliar and unstable environments and disrupted education. This may lead to psychosocial delays and hinder their long-term development and well-being (Bürgin et al., Reference Bürgin, Anagnostopoulos, Vitiello, Sukale, Schmid and Fegert2022). The impact of displacement on mental health is often exacerbated by a lack of adequate support, including access to mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) services, which can be limited in LMICs. Addressing the mental health needs of displaced populations is therefore crucial to improving their quality of life, well-being and long-term prospects (Sheath et al., Reference Sheath, Flahault, Seybold and Saso2020).

To shed light on how MHPSS interventions can be improved to better serve displaced populations and their mental health needs, it is paramount that their delivery systems, particularly the ways in which they are implemented, be considered (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Lasater, Lee, Mallawaarachchi, Joshua, Bassett and Gelsdorf2023). The successful implementation of MHPSS interventions for populations affected by humanitarian crises is often hindered by a plethora of factors encompassing discrimination, stigma and distrust (Perera et al., Reference Perera, Salamanca-Sanabria, Caballero-Bernal, Feldman, Hansen, Bird, Hansen, Dinesen, Wiedemann and Vallières2020; Massazza et al., Reference Massazza, May, Roberts, Tol, Bogdanov, Nadkarni and Fuhr2022). More specifically, in the case of displaced populations, challenges can stem from diverse cultural backgrounds and experiences, as well as the adverse experiences they have been exposed to Im et al. (Reference Im, Rodriguez and Grumbine2021).

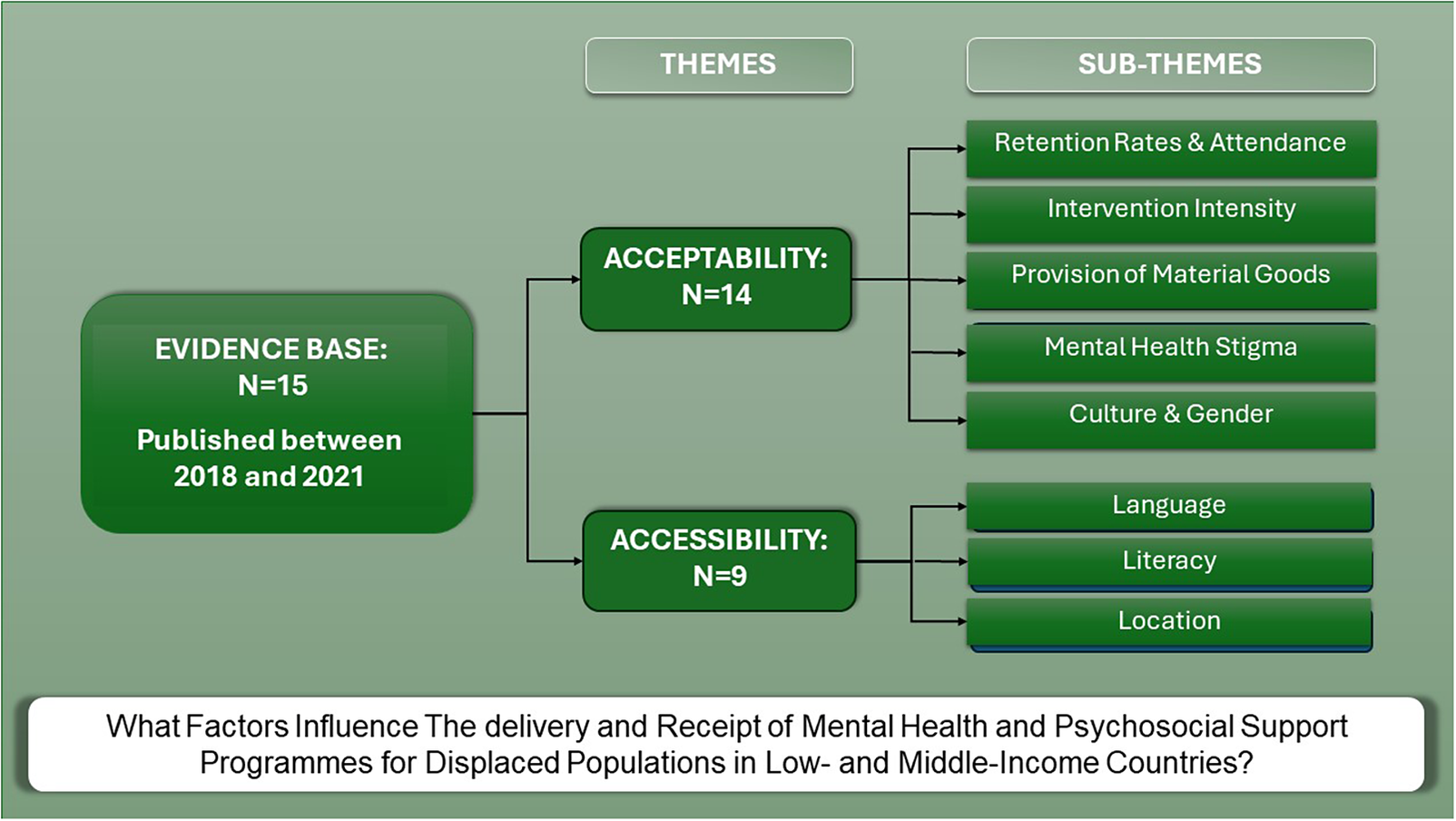

Primary research and systematic reviews in this area largely assume the form of impact evaluations assessing the effectiveness of MHPSS interventions (Uphoff et al., Reference Uphoff, Robertson, Cabieses, Villalón, Purgato, Churchill and Barbui2020). While reviews on the delivery and receipt of such interventions remain far fewer, often reflecting the smaller number of primary studies evaluating implementation, particularly in the global south. Given the paucity of evidence synthesis to date, this systematic review aims to fill this gap by answering the following research question ‘What factors influence the delivery and receipt of MHPSS programmes for displaced populations in LMICs?’ By synthesising data on processes and perspectives, we aim to provide a comprehensive overview of the delivery mechanisms that need to be taken into consideration to ensure successful programme implementation and outcomes.

Methods

This systematic review was described a priori in a research protocol (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Lambert, Chiumento and Dickson2016), and adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidance found in Supplementary S1 (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009).

Search strategy

We searched 12 bibliographic databases across disciplines and specialist databases: Medline, ERIC, PsycINFO, Econlit, Cochrane Library, IDEAS, IBSS, CINHAL, Scopus, ASSIA, Web of Science and Sociological Abstracts. Both published and unpublished studies were comprehensively searched from the websites of relevant organisations. We searched the citations of included studies and relevant systematic reviews. Search strategies were informed by the scoping exercise (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Lambert, Chiumento and Dickson2016) and were developed based on three key concepts (mental health and psychosocial, humanitarian emergencies and study designs). The scoping exercise was instrumental in ensuring we used a comprehensive list of terms for mental health and psychosocial programmes and outcomes that went beyond psychological ‘ill’ health, and terms which could capture implementation data from the perspectives of providers or recipients of MHPSS programmes.

The search was first performed in November 2015 to inform previous reviews on the effectiveness (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix and Dickson2019) and barriers and facilitators of delivering MHPSS programmes for people affected by humanitarian crises (Dickson and Bangpan, Reference Dickson and Bangpan2018). This search was updated and finalised in May 2023 to inform this paper (see Supplementary S1 for the example of database search strategies and a list of websites searched).

Eligibility criteria

To capture evidence that could answer our review question, we included studies published in English from 2013 onwards if they contained qualitative or quantitative data on the delivery and/or receipt of MHPSS programmes for displaced populations affected by humanitarian emergencies in LMICs. To ensure we identified a wide range of interventions, we adhered to the Inter-Agency Standing Committee’s definition of MHPSS and included any programme seeking ‘to protect or promote psychosocial well-being and/or prevent or treat mental disorder’ (Inter-Agency Standing Committee, 2006, p. 11). We defined humanitarian emergencies as natural or man-made emergencies, including both slow-onset and sudden crises, and used the World Bank classification system was used to categorise countries based on their level of economic development (Fantom and Serajuddin, Reference Fantom and Serajuddin2016). We took a broad view of displacement to refer to individuals or groups of people who have been forced to leave their homes due to conflict, violence, persecution, natural disasters or other reasons and are unable to return to their communities of origin. This displacement, which often results in different types of settlement status (e.g., status of an individual or group in relation to their residency or citizenship in a particular place or country), could be temporary or permanent. Thus, to guide this review and operationalise displacement, we screened studies using the United Nations Refugee Agency definitions for refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced populations derived from the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees.

Two reviewers (MB and KD) piloted the eligibility criteria. A pilot screening exercise was performed by review team members (MB, KD, CN) before independently screening the studies on titles and abstracts. When there was insufficient information, full reports were obtained to assess the eligibility for inclusion. Double screening was conducted in pairs, on all full texts.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

A fit-for-purpose data extraction tool was used to capture key dimensions to answer the review question and provide study context details. Key information included the following: bibliographic details, participant and intervention characteristics, study methods and findings (see Table 1). Piloting and refinement of the tools took place before the commencement of full coding. We used the EPPI-Centre quality appraisal tool, appropriate for qualitative and mixed methods studies of process data (Dickson et al., Reference Dickson, Melendez-Torres, Fletcher, Hinds, Thomas, Stansfield, Murphy, Campbell and Bonell2018; Dickson and Bangpan, Reference Dickson and Bangpan2018), to determine the trustworthiness of the evidence based according to two key dimensions: reliability and usefulness. Criteria to judge reliability are achieved by evaluating efforts to minimise bias and/or increase rigour in the sampling, data collection, and data analysis processes; and takes into account the studies’ ability to demonstrate how findings and conclusions were derived from the collected data, as well as whether the studies’ findings had achieved breadth (i.e., considered the perspectives of multiple participants) or depth (i.e., if the study made insightful and meaningful contributions to existing literature, concepts or theories). Criteria to judge usefulness in answering the review question take into consideration the reflexivity of the primary study authors, namely, through whether they had considered the power relations between themselves and the participants, and if steps were taken to assure participants of their rights and confidentiality. The approach to determining the overall quality of each study according to each dimension is provided in Supplementary S1. To support quality assurance processes, data extraction and quality appraisal were performed by at least two members of the research team, and any discrepancies were discussed and reconciled with a third member of the team.

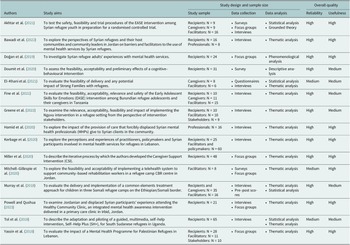

Table 1. Key characteristics of the intervention and context of delivery

Data synthesis

Using an EPPI reviewer, at least two authors extracted key ideas and concepts of each included study pertaining to factors that influenced the delivery of MHPSS interventions. The data analysis was carried out using thematic synthesis (Thomas and Harden, Reference Thomas and Harden2008) and drawing on elements of Noblit and Hare meta-ethnographical approach to synthesis (Noblit and Hare, Reference Noblit and Hare1988). We chose a hybrid approach to support the integration of both qualitative and quantitative data and ensure we were sensitive to negative case examples and contradictory findings within any given theme. This approach was supported by identifying ‘reciprocal translations’, where concepts extracted across studies were similar and could be incorporated into one another to create higher level themes, as well as ‘refutational translations’, where concepts are similar enough to group together but provide ‘negative case examples’ or contradictory findings (Uny et al., Reference Uny, France and Noblit2017). For the former, common themes emerged as a product of the synthesis, whereas in the case of the latter, we explored the reasons for the contradictions as part of the synthesis. We integrated the identified ‘reciprocal translations’ and ‘refutational translations’ using a ‘line of argument’ synthesis, creating an overall narrative of the delivery and receipt of MHPSS interventions for displaced populations (Brookfield et al., Reference Brookfield, Fitzgerald, Selvey and Maher2019). This narrative informed our recommendations for the future design of such interventions.

Results

Search results

We identified 18,557 references, in which 17,488 references were screened on the basis of title and abstract, and 1,343 references were rescreened on the basis of the full-text reports. A total of 15 studies were included in the review (see Figure 1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart).

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flowchart.

Characteristics of studies

An overview of the included studies is provided in table 1 and table 2. Studies were published between 2018 and 2021, with sample sizes ranging between 8 and 85 (see Table 2). The aims of the studies were relatively varied, with a sizeable number examining feasibility, acceptability and accessibility. Study designs utilised across the studies were either of a qualitative (e.g., conducting interviews and focus groups to understand the perceptions and experiences of displaced populations and programme providers) or mixed-methods nature (e.g., also conducted statistical analysis, such as measures of attendance).

Table 2. Aims, methods and overall quality of studies

The studies were centred on displaced populations related to the civil war in a range of countries in South Asia (n = 1), Africa (n = 3) and the Middle East (n = 8), with roughly half the studies pertaining to the civil war in Syria (n = 6) (see Table 1). Barring one exception (El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021), the respective MHPSS implementation sites of each study was situated in neighbouring countries within the same continent. Among the studies, two categories of MHPSS were recurrent (see Table 1). The first was interventions that sought to support and/or educate displaced caregivers and parents (n = 5), such as Early Adolescent Skills for Emotions (EASE), the Strong Families Programme, Caregiver Support Intervention (CSI) and the common elements treatment approach for youth (CETA-youth). These studies investigated caregiver-child dyads. The second was the provision of general mental health services (n = 4). Cultural adaptation of programmes varied across studies, with some drawing on stakeholders prior to implementation to ensure they were sensitive to local contexts, while other studies considered cultural suitability and the need for adaption as part of the programme evaluation (further details are provided in Supplementary S1).

Quality of studies

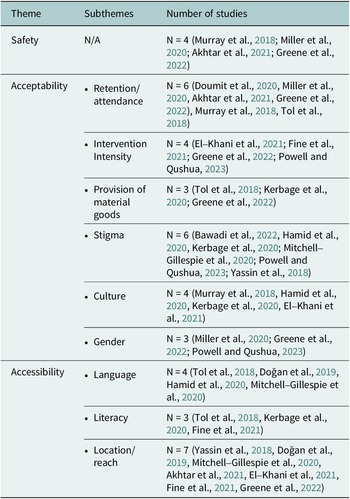

The findings of this review are grounded in a strong evidence base. Overall, study quality was judged to be of high or medium reliability and usefulness, with none of the studies judged to be of low quality on either dimension (see Table 2). More than half of the studies (N = 9) were judged to have met all of the criteria established by the tool (e.g., they took steps to minimise bias and increase rigour in sampling, data collection and analysis, ensured their findings were grounded in the data, achieved breadth and/or depth in their findings and privileged the views of participants). Of the remaining six studies, four scored at least ‘high’ or ‘medium in at least one of the two dimensions and two studies were judged as medium on both dimensions (see Supplementary S1 for a full breakdown of study quality)

Synthesis

An overview of the themes are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Overview of themes and subthemes

Theme 1: Safety

Programme safety was investigated in three studies (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022). Two studies evaluated the feasibility of the EASE intervention; one delivered to Syrian refugees and their caregivers in Jordan (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021) and the other with Burundian refugee adolescents and their caregivers in Tanzania (Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021). The remaining study programme focussed on MHPSS approaches to reduce psychological distress in Congolese refugee women who had experienced intimate partner violence (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022). All three programmes put safety protocols in place to ensure participants were protected from harm. Greene et al. (Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022) took steps to retain the privacy of involvement in the intervention ‘given concerns that this may be unacceptable to their partners and may put women at increased risk of violence’ (pp. 2874–2875). This was achieved by presenting the programme to be about women’s overall health and well-being and selecting community members as facilitators to increase trust. Despite this, ‘some women nevertheless struggled with getting permission from their partners to attend sessions’ (p. 2875). However, overall, no adverse events were made known during the study, and confidentiality was reported as high among both the participants and facilitators. Similarly, no adverse events were reported ‘for children or caregivers’ participating in the Jordan-based EASE programme, ‘including during the screening and assessment phases’. Overall, the trial protocols indicated that ‘appropriate safeguarding of children and identification of those most-at-risk’ (p. 10) were in place. The authors suggested that, this would not have been the case if ‘during the screening, two children were found to be at-risk of suicide’ were not ‘immediately referred to child protection services for appropriate support (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021, p. 10). The safety procedures in the Tanzania-based study by Fine et al. (Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021) also ensured that any participants experiencing significant distress and/or violence during the intervention would receive referrals to specialised services. Of the 24 adverse events reported to the Data Safety Monitoring Board, only one was found to be related to the intervention. This was due to a non-participant who was ‘harassing adolescent participants due to tensions over not receiving the EASE sessions’ (p. 8) rather than participating in the intervention itself. To address this, the authors noted a greater need for privacy by ensuring ‘a discreet yet accessible location’ was chosen for programme delivery, particularly for participants who live ‘in close-residing communities such as a refugee camp’ as well as ‘greater geographical distance between the intervention and control conditions, and the implementation of non-therapeutic structured activities’ for participants who had been screened out (Fine et al. p. 9).

Theme 2: Acceptability

The acceptability of MHPSS programmes was a key theme in 14 of the included studies (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid and Harrison2018; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018; Yassin et al., Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018; Doumit et al., Reference Doumit, Kazandjian and Militello2020; Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020; Kerbage et al., Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Ghalayini, Arnous, Tossyeh, Chen, van den, Koppenol-Gonzalez, Saade and Jordans2020; Mitchell-Gillespie et al., Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020; Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021; El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021; Bawadi et al., Reference Bawadi, Al-Hamdan, Khader and Aldalaykeh2022; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022; Powell and Qushua, Reference Powell and Qushua2023). The six sub-themes included: i) retention rates and attendance, ii) intervention intensity, iii) provision of material goods, iv) the stigma associated with mental health, v) culture and vi) gender.

Retention/attendance

Although many factors can influence programme attendance, such as accessibility and scheduling constraints, attendance rates were mostly used as a proxy for programme acceptability. Five studies collected attendance data to assess programme feasibility and support future implementation strategies (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid and Harrison2018; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018; Doumit et al., Reference Doumit, Kazandjian and Militello2020; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Ghalayini, Arnous, Tossyeh, Chen, van den, Koppenol-Gonzalez, Saade and Jordans2020; Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021). For example, the three-phase evaluation by Miller et al. (Reference Miller, Ghalayini, Arnous, Tossyeh, Chen, van den, Koppenol-Gonzalez, Saade and Jordans2020) reports high engagement with the CSI, with no dropouts, and a total of 85% of adult Syrian refugees ‘completing seven or all eight of the sessions’ (p. 5). In phase 2, the rates remained high but fell slightly, with 75% of women and 73% of men attending at least seven of the nine sessions. Furthermore, ‘11 of the 38 men in Lebanon dropped out of the intervention, as did nine of the 36 women’ (p. 6) compared to the Gaza site where there were no dropouts. The reasons for this attrition were explored via interviews and rectified to ensure higher attendance rates in phase 3. Addressing programme content and delivery mechanisms proved to increase the attendance rates to ‘95% of women and 86% of men completing at least seven of the nine sessions’ (pp. 7–8). High attendance rates were also reported by Akhtar et al. (Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021), with 78.78% of participants attending at least five out of seven EASE sessions’ (p. 7). When evaluating the CETA for children in three Somali refugee camps on the Ethiopian/Somali border, Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid and Harrison2018) found that caregivers were engaged and attended an ‘average of 9.42 sessions out of 13′ (p. 8).

Although favourable satisfaction rates (e.g., a mean rating of 8.54/10.00, SD = 0.13) were reported in the study by Doumit et al. (Reference Doumit, Kazandjian and Militello2020), for ‘unknown reasons’, six Syrian refugees participating in the Lebanon CBT-based programme for ‘were lost to attrition by the second session’ (p. 230). However, an overall retention rate of 77.5% was achieved by the end of the study (N = 31 participants).

In Tol et al.’s (Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018) pilot study of Self-Help Plus (SH+), for South Sudanese refugees in Uganda, they found variation in attendance rates among male and female participants. For example, the attendance in the female group was high, with ‘76% of women (n = 25) missing none or one (out of five) sessions, and a further 25% (n = 8) missed two or three sessions’ (p. 6). The attendance ‘in the male group was mixed with 38% of men (n = 12) missing none or one (out of five) sessions, 31% (n = 10) missed two or three sessions, but 31% (n = 10) missing four sessions’ (p. 6); suggesting there were some gender differences related to acceptability (see section 2.6).

Intervention intensity

Four studies made observations about increasing the intensity and duration of MHPSS interventions. Greene et al. (Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022) noted that ‘participants, facilitators, research staff and members of the community advisory board described the desire for continued delivery of Nguvu sessions’ (p. 2873). Resettled Syrians also expressed a strong desire for continued involvement in an integrated mental health awareness intervention delivered in primary care clinics in Jordan (Powell and Qushua, Reference Powell and Qushua2023), including the need for more information ‘about mental health, addictions and everything’ (p. 168). Caregivers participating in the Strong Families Programme also ‘expressed an interest in continuing to learn family skills and more involvement’ with several suggesting they did not want the programme to end (El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021, p. 14). In the Tanzanian-based EASE study, both adolescents and their caregivers ‘gave positive feedback on the length and frequency of EASE sessions’ but many also found that they ‘would have benefited from more and/or longer sessions (p. 6).

Provision of material goods

There was a misconception among participants in the three studies that they would receive material and financial aid alongside mental health support. Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018) report that ‘the fact that no basic goods or services were provided as part of SH+ delivery was one of the primary challenges… mentioned by all participants’ (p. 9). This was despite repeated attempts to communicate that mental health was the primary aim of the intervention. ‘Similarly, there were expectations across stakeholder groups that they would be provided with material or financial support related to their different roles and participation’ in the study by Greene et al. (Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022). In many cases, participants requested ‘small items (e.g., soap, food) or financial support during Nguvu sessions similar to the compensation they received when completing research interviews’ (p. 2874). Providers of mental health services in the study by Kerbage et al. (Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020) commented that participants ‘want a job, material aids, but we tell them we cannot help them materially but psychologically’ (p. 6). The study authors also noted that providers often ‘complained that Syrians repeatedly asked about material aid in therapeutic settings’ making it difficult for them to communicate the value and need to attend to their mental health (p. 7).

Stigma

Stigma surrounding the need for and use of mental health services was a recurring theme in six studies (Yassin et al., Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018; Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020; Kerbage et al., Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020; Mitchell-Gillespie et al., Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020; Bawadi et al., Reference Bawadi, Al-Hamdan, Khader and Aldalaykeh2022; Powell and Qushua, Reference Powell and Qushua2023). The studies largely concluded that mental health treatment was associated with negative labels such as the term ‘crazy’ within the investigated contexts making engagement with mental health programmes less acceptable amidst displaced populations (Bawadi et al., Reference Bawadi, Al-Hamdan, Khader and Aldalaykeh2022, p. 199; Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020, p. 8; Kerbage et al., Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020, p. 4; Yassin et al., Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018, p. 394). The studies also suggested that MHPSS users would bring shame to, or face rejection from, loved ones and the community due to social stigma. For example, in Yassin et al. (Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018), ‘a few patients reported that family members still did not accept their illness, sometimes criticising them’ (p. 394) and women in the study by Bawadi et al. (Reference Bawadi, Al-Hamdan, Khader and Aldalaykeh2022) were less likely to seek mental health support in case it causes ramifications in their relationships. For example, one participant shared that: ‘If my husband knows I have been visiting the mental health clinic he will divorce me’ (female 22 years).

Mitchell-Gillespie et al. (Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020) reported the perceived likelihood by community-based rehabilitation (CBR) workers that parents of children undergoing CBR would be reluctant to have CBR sessions filmed for fear that they ‘will be published’ or ‘distributed’ (p. 10). While the participants in Kerbage et al. (Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020) ‘did not feel ashamed’ for using mental health services, they had mentally segregated themselves from sufferers of mental illness, regarding their symptoms as ‘a normal and collective reaction to their situation’ (p. 8). Therefore, what appears to be a discrepancy reported by Kerbage et al. (Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020) does not contradict the notion that mental illness was associated with shame and rejection. Given the stigma associated with MHPSS and the possible repercussions of using such services, intervention recipients were generally fearful that they would be found out. In Yassin et al. (Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018), a participant expressed that they did not ‘want anyone to know’ (p. 394) about them receiving treatment, while in Hamid et al. (Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020), it was acknowledged that seeking treatment was ‘often not spoken about’ as people generally ‘do not tell each other that we need help’ (p. 5).

Culture

Culture was another key factor that influenced the acceptability of mental health interventions among displaced populations (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid and Harrison2018; Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020; Kerbage et al., Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020; El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021). Overall, studies showed that recipients engaged better when MHPSS interventions took into account of the cultural context. For example, in El-Khani et al. (Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021), ‘caregivers and facilitators’ deemed the Strong Families intervention to be ‘culturally appropriate’. As one participant reflected “What we learnt (in the intervention) is all in our religion; to respect each other, our families as well and respect the elderly” (p. 13). This led the authors to perceive this as one of the reasons for participants’ ‘engagement and satisfaction’ (p. 13). A similar observation is also noted in Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid and Harrison2018), which discusses how ‘clients’ religious and cultural views’ influenced their ‘level of engagement’ (p. 10).

Three studies explicated how and/or why recipients’ religious beliefs impacted their acceptance of MHPSS programmes. In El-Khani et al. (Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021), one participant indicated that the Strong Families intervention aligned well with their Islamic beliefs, which place emphasis on ‘family’ and ‘respect’ for the ‘elderly’ (p. 13). Likewise, in Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Hall, Dorsey, Ugueto, Puffer, Sim, Ismael, Bass, Akiba, Lucid and Harrison2018), participants were sceptical and considered ‘counselling a somewhat foreign form of treatment’ due to their belief that ‘mental health issues came from a higher religious power’ (p. 10). As such, the most common solution was ‘to have the afflicted parties read religious scripture’ (p. 10). Finally, in Hamid et al. (Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020), mental health professionals pinpointed that their understanding of clients’ ‘religious norms and practices’ (p. 4), such as their nuanced comprehension of ‘the male–female relationship in relation to disclosing emotional experiences’ (p. 4), helped them to make appropriate and acceptable decisions for their clients, such as referring male professionals to male clients and vice versa.

Correspondingly, tensions arose when mental health professionals were unable to understand the cultural norms of their clients, which adversely affected professionals’ acceptability of their clients. As illustrated in Kerbage et al. (Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020), Lebanese mental health practitioners equated ‘Syrian culture with behavioural ineptitude’, which prevented them from ‘identifying with the displacement experience’ of their clients (p. 11). Further, these practitioners determined Syrian culture to be an ‘obstacle’ (p. 11) to the effective delivery of mental health services given that Syrian refugees do not have the ‘culture for mental health’ and ‘do not see the need for’ or ‘understand why they should come’ (p. 6) to such services.

Gender

Different responses to programme content and structure along gender lines were highlighted in three studies (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Ghalayini, Arnous, Tossyeh, Chen, van den, Koppenol-Gonzalez, Saade and Jordans2020; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022; Powell and Qushua, Reference Powell and Qushua2023). Miller et al., Reference Miller, Ghalayini, Arnous, Tossyeh, Chen, van den, Koppenol-Gonzalez, Saade and Jordans2020 noted that there was a ‘reluctance among men to try the stress management exercises’ without understanding ‘the science behind them’ (p. 7) compared to women’s enthusiasm. This contrasted with male participants’ willingness to engage in frustration and anger management techniques that they ‘viewed quite positively’ (p. 7). Content on early childhood development was also perceived as ‘irrelevant’ by men, who believed that they ‘had essentially no role to play in the raising of children below the age of 5’, with one man suggesting that, ‘from zero to four there is nothing to talk about.’ (p. 7). This differed from the female participants who ‘requested more ‘quality time’ activities they could engage in with very young children, and to have these available in recorded form like the relaxation exercises’ in addition to ‘a written manual with all of the parenting methods and activities learned in the sessions’ (p. 7). In the strengths-based and solution-focussed MHPSS programme evaluated by Powell and Qushua (Reference Powell and Qushua2023), there were suggestions that gender-separated groups would be preferable. As ‘sometimes there are questions males want to ask but they feel shy and the same with women they want to ask question and they feel shy to ask, so later we ask the questions individually’ (p. 168). Some women also found that exercises could be difficult to engage in due to the religious dress code. One stated, ‘it was a little bit of a problem for the full cover, hijab wearing women’ and another that ‘it stressed me out a little because I had to cover my face the whole time which caused difficulties breathing and seeing’. (p. 168). However, designing programmes according to gender preferences might not always be appropriate. Greene et al. (Reference Greene, Scognamiglio, Likindikoki Samuel, Misinzo, Njau, Bonz, Ventevogel, Mbwambo Jessie and Tol Wietse2022) ‘described the importance of including and involving men’ as their programmed specifically focussed on ‘on efforts to reduce gender-based violence’ (p. 168).

Theme 3: Accessibility

The accessibility of MHPSS programmes to local recipients was a key theme in nine studies (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018; Yassin et al., Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018; Doğan et al., Reference Doğan, Dikeç and Uygun2019; Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020; Kerbage et al., Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020; Mitchell-Gillespie et al., Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020; Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021; El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021). Sub-themes included i) language in which the programme was delivered compared to that of recipients, ii) the lack of literacy of programme recipients and iii) the location of services.

Language

Language can be a significant barrier when delivering MHPSS programmes to displaced populations in LMICs, limiting accessibility. Four studies addressed the important role of language in the delivery of MHPSS interventions, with two considering the perspectives of intervention recipients (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018; Doğan et al., Reference Doğan, Dikeç and Uygun2019) and two considering the perspectives of mental health professionals delivering the intervention (Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020; Mitchell-Gillespie et al., Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020). From these studies, both parties concurred that effective communication in languages understood by MHPSS recipients is essential for the accessibility of programmes. In Doğan et al. (Reference Doğan, Dikeç and Uygun2019), Syrian refugees revealed that their access to mental health services was limited as there was ‘only one Arabic-speaking doctor’, and when the doctor was unavailable, they ‘could not get prescriptions’ (p. 678). The lack of Arabic-speaking staff also meant that they ‘could not make appointments’ and had hindered access to ‘tests, medical imaging and medical reports’ (p. 676). In a similar vein, Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018) revealed a demand for MHPSS materials, including ‘audio-recording(s), illustrated manual(s) and worksheet(s)’, to be available in ‘different languages’ so as to cater to recipients ‘from different ethnic tribes’ (p. 9). The inability to do so would likely lead to the recipient’s discomfort and incompletion of MHPSS programmes, impeding accessibility. Recipients’ perceptions of language as a barrier to accessibility are also supported by CBR workers’ views in Mitchell-Gillespie et al. (Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020). They determined the ‘lack of Arabic interface’ in CBR telehealth services as a major barrier to access, recommending a ‘built-in translation service’ for the accessibility of ‘participants not speaking the same language’ (p. 9). Correspondingly, Hamid et al. (Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020) support the notion of language as a facilitator for accessibility through Syrian mental health professionals’ perception that their proficiency in ‘Syrian dialects’ enabled them to understand their clients’ ‘cultural, religious, political and social contexts’ and provide ‘words of comfort appropriately’ (p. 4).

Literacy

Like language, illiteracy was also portrayed as a barrier to accessing MHPSS programmes in three studies (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018; Kerbage et al., Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021). This was especially noticeable for programmes involving the use of materials. Fine et al. (Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021) reported that MHPSS materials for the EASE intervention, characterised by ‘graphics and stories’, were generally regarded as ‘easy to understand, and accessible to non-literate participants’ (p. 7). However, there was still feedback about challenges for those with literacy issues, putting forth the need for additional efforts to cater to the lack of literacy among Burundian refugees. Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, Garcia-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van2018) presented a similar issue with the illustrated manual and worksheets used in SH+, whereby intervention facilitators mentioned that participants who ‘were unable to read and write’ had to ‘take their books to their children or neighbours to read it for them’ (p. 9), establishing a connection between illiteracy and reduced accessibility. This connection is elucidated in Kerbage et al. (Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020) in a different manner. Mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, perceived low levels of literacy as an indication that intervention recipients were ‘ignorant’ and ‘not educated’ (p. 5), and were convinced that illiteracy accounted for the latter’s ‘resistance to mental health treatment’ (p. 6). These negative attitudes towards illiteracy insinuate that such services were not friendly or accessible to non-literate individuals.

Location/reach

The theme of location or site of MHPSS delivery was explored in six studies (Akhtar et al. (Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021), Doğan et al., Reference Doğan, Dikeç and Uygun2019, El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021, Fine et al., Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021, Mitchell-Gillespie et al., Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020, Yassin et al., Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018). All studies concurred that location plays a significant role in determining participants’ accessibility to the interventions. Fine et al. (Reference Fine, Malik, Guimond, Nemiro, Temu, Likindikoki, Annan and Tol Wietse2021) found that the appropriate ‘distance and location of sessions’ was one of the factors contributing to the ‘feasibility’ of the EASE (p. 6), while in El-Khani et al. (Reference El-Khani, Haar, Stojanovic and Maalouf2021), location was recognised by a facilitator as having an influence on the reach of the Strong Families intervention. The facilitator thus recommended also implementing the intervention in other reception centres to allow ‘everyone’ to benefit (pp. 13–14). Yassin et al. (Reference Yassin, Taha, Ghantous, Atoui and Forgione2018) affirm a similar notion through an MHPSS provider attributing regular attendance at ‘follow-up appointments’ to the centre’s accessibility and ‘close proximity to the camp’, which meant that ‘travel time and cost were not a challenge’ for recipients (p. 390). Likewise, Mitchell-Gillespie et al. (Reference Mitchell-Gillespie, Hashim, Griffin and AlHeresh2020), CBR workers and managers, recognised that CBR delivered through telehealth would enable ‘more people to use such services’, suggesting that access and reach were confined by physical geographical location (p. 10–11).

In the same way, delivery sites that were situated far away from recipients’ residence impeded access due to their inability to afford transportation costs. EASE participants in Akhtar et al. (Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021) cited ‘financial concerns related to initial cost of transportation to EASE locations’ as one of the ‘greatest barriers to attendance’ (p. 8). Recipients in Doğan et al. (Reference Doğan, Dikeç and Uygun2019) echo similar views, finding taxi rides to the hospital ‘economically challenging’, but were also faced with limited options as ‘public transport is difficult’ (p. 674).

Discussion

Addressing issues related to the acceptability and accessibility of MHPSS programmes is key to their successful delivery and uptake (Dickson and Bangpan, Reference Dickson and Bangpan2018). Evidence on acceptability has provided important insights about how displaced populations are currently engaging with MHPSS programmes in LMICs. Similarly, issues related to accessibility have highlighted important themes about the practical barriers and facilitators to utilising programmes.

Stigma as a result of cultural and gender norms were key factors influencing the acceptability of MHPSS programmes. The stigma associated with needing and receiving help for mental health issues is evidenced across cultures and intersects with gender (Elshamy et al., Reference Elshamy, Hamadeh, Billings and Alyafei2023; Khatib et al., Reference Khatib, Alyafei and Shaikh2023). This review concurs with existing evidence to suggest that both ‘self-stigma’ (e.g., internalised sense of shame or feeling devalued due to mental health issues) and ‘societal stigma’ (e.g., whereby communities may stigmatise individuals with mental health issues) can impede the uptake of services (Bawadi et al., Reference Bawadi, Al-Hamdan, Khader and Aldalaykeh2022; Abo-Rass et al., Reference Abo-Rass, Abu-Kaf, Matzri and Braun-Lewensohn2023). While mental health issues affect both men and women, traditional gender roles may prevent men from seeking help or discussing their emotional struggles as openly as women due to the stigma attached with doing so (Khatib et al., Reference Khatib, Alyafei and Shaikh2023). Cultural and gendered beliefs among displaced communities may stigmatise mental health issues, viewing them as personal failures or signs of weakness (Elshamy et al., Reference Elshamy, Hamadeh, Billings and Alyafei2023). Gender-specific barriers were observed in responses to certain programme components. With men showing reluctance towards activities perceived as ‘less masculine’, while women expressed enthusiasm for activities emphasising quality time and gender-separated groups. Limited understanding and awareness about how displacement can impact mental health can also contribute to further stigma (Abo‐Rass et al., Reference Abo‐Rass, Nakash and Abu‐Kaf2023).

Given the negative perceptions that can be associated with mental health, interventions that provide psychoeducation about the importance of and necessity for good mental health and psychosocial well-being could also be beneficial prior to and during implementation. This could also be informed by an understanding of how psychological distress is perceived and articulated across different population groups to support greater cultural and gender sensitivity of programming (Hamid et al., Reference Hamid, Scior and Williams2020). Promoting MHPSS in a positive light may assure local communities that addressing their mental health is an indication of strength rather than a source of shame, thereby reducing the levels of stigma associated with MHPSS services. Greater consideration should also be given to the aims and objectives of MHPSS to decide whether programme components need to be tailored along gendered lines or whether single or mixed sex programming is most appropriate. Targeting the inclusion of men in MHPSS programmes, could also support efforts to reduce any gender disparities in mental health outcomes and enhance family and community dynamics. Our synthesis has also shown that religion can play a fundamental role in how local communities engage with MHPSS programmes. Individuals were much more open to programmes that reflected their religious beliefs. Thus, it would be helpful to assess the extent to which MHPSS programmes reflect the values of the communities they are serving and whether they would benefit from embedding religious beliefs into core programme components to further enhance their receptivity.

The second theme, accessibility, contained three sub-themes: language, literacy and location/reach. For the purposes of this review, literacy referred to the capacity to read and write, whereas language proficiency denoted the ability to communicate effectively in a second language. While there can be overlap, it is important to note that when accessing programmes, individuals with limited literacy could also face challenges in understanding the written materials, including when in their own language. Thus, it is important for programme implementers to bear in mind that displaced populations may be limited by educational levels as well as linguistic, financial and familial constraints. As such, ensuring that the materials and services are made available in the appropriate language and medium (e.g., pictures and diagrams instead of words, audio methods of delivery etc.) for the target population is indispensable for the successful delivery of interventions. Engagement with programme materials at this level could also be coupled with training on sensitive care models to help avoid stereotypes of illiterate participants as “ignorant” and ‘resistant’ to treatment (Kerbage et al., Reference Kerbage, Marranconi, Chamoun, Brunet, Richa and Zaman2020).

MHPSS programmes were often delivered in person and in close proximity to participants’ residence to increase ease of access and time constraints. However, this also raised issues of privacy and safety due to the visibility of programme participation (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Malik, Ghatasheh, Aqel, Habashneh, Dawson, Watts, Jordans, Brown, Sijbrandij, Cuijpers and Bryant2021). Further flexible programming (e.g., offering multiple timeslots or multiple locations) could help in accommodating these concerns, including pressing familial commitments the displaced populations may have. Finally, enabling displaced populations to access the delivery site with ease, through providing transportation services to and from the delivery sites or a transportation stipend, might be another aspect to consider in enhancing the accessibility of the interventions. Delivering services through information and communication technology might also be an option to save travel time and costs. However, this may largely be dependent on the availability of electronic devices and a stable internet connection. Our findings echo ongoing calls for pragmatic programming that considers the wider socioeconomic context of delivery of displaced population (Jannesari et al., Reference Jannesari, Lotito, Turrini, Oram and Barbui2021).

Strengths and limitations

This review builds on previous qualitative and mixed method approaches to produce a robust and transparent approach to evidence synthesis. By synthesising evidence on similar populations and interventions across a diverse set of research objectives, we were able to identify common themes and patterns within a complimentary but varied data set. However, in doing so, we also found that studies using different methods, measures and frameworks to evaluate processes can make it difficult to draw meaningful comparisons between them. Similarly, including data drawn from outcome evaluations ensured that we captured important insights about the safety and feasibility of programmes. However, as noted by Nemiro et al. (Reference Nemiro, Jones, Tulloch and Snider2022), it is important to acknowledge that in less controlled settings, the implementation of MHPSS interventions may differ considerably, potentially resulting in divergent participant experiences compared to those observed within a more tightly controlled environment required for evaluations, such as RCTS.

Although this review has synthesised the perspectives and experiences of displaced populations receiving MHPSS interventions and providers of those programmes, due to lack of resources, we were unable to consult with key stakeholders to explore if this research resonates with their concerns and experiences or consider implications of the findings; future research will benefit from such engagement. Studies conducted in languages other than English and published prior to 2018 could also provide insights not included in this review. Nevertheless, in light of these limitations, we were able to produce a comprehensive synthesis that explores key delivery mechanisms potentially contributing to the success or failure of MHPSS programmes targeting displaced populations.

Conclusion

This review synthesised evidence on the process to gain insight into factors influencing the delivery and receipt of MHPSS programmes for displaced populations in LMICs. Based on our findings, it is recommended that future MHPSS programmes should address issues of accessibility and acceptability that are specific to local contexts to ensure successful uptake and retention of MHPSS programmes. Attention should be paid to designing programmes that account for existing gender and cultural norms to limit stigmatisation associated with mental health and increase the sensitivity and relevance of programme content to target populations. Consideration should also be given to whether programmes can be flexible in timing, location and language, in order to maximise their reach. Future programme design and evaluation would also benefit from stakeholder engagement prior to commencement to ensure that efforts to achieve cultural adaptivity remain a priority.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.56.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2024.56.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, references and/or its Supplementary Materials.

Author contribution

M.B. and K.D. designed the study, developed and wrote the initial draft of protocol. C.N. decided the scope of the updated review on displaced population. K.D. managed the overall project. M.B. and K.D. developed the search strategy. M.B. updated the search. M.B. and C.N. screened title and abstracts. K.D., J.S.K., C.N. and D.M. retrieved the full texts and double screened all studies. K.D., J.S.K., C.N. and D.M. performed data extraction and quality assessment of the included studies. J.S.K., C.N. and D.M. prepared and finalised the data tables. K.D. and J.S.K. planned and conducted the final write-up of the synthesis. J.S.K. wrote the initial draft of the introduction and methods. K.D. and J.S.K. wrote the discussion and conclusions. K.D. led the writing of the remainder of the manuscript with all other authors contributing to its revision and finalisation. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and gave final approval for submission.

Financial support

Oxfam/Feinstein.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Ethics statement

We followed the UCL research ethics framework, and complied with the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Research Ethics Framework to ensure that all potential ethical considerations were identified and addressed.