Therapeutic trials of the n-3 essential fatty acids (EFAs) eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) have yielded promising data for a broad spectrum of psychiatric disorders (Reference Hallahan and GarlandHallahan & Garland, 2005). Moreover, rapid advances in the basic science have confirmed the central role of the n-3 EFAs in a variety of pathophysiological processes, particularly those involving monoaminergic neurotransmission (Reference Sublette, Russ and SmithSublette et al, 2004). Patients with recurrent non-fatal self-harm exhibit affective disturbances and impulsive and violent behaviours that have been repeatedly linked to deficits in monoaminergic (particularly serotonergic) neurotransmission (Reference MannMann, 2003). Self-harm is a major cause of morbidity worldwide and presents a major therapeutic challenge. This single-centre 12-week randomised active placebo-controlled trial is the first of n-3 EFA supplementation in patients with self-harm.

METHODS

Setting

All participants were recruited from the accident and emergency (A&E) Department of Beaumont Hospital, an academic teaching hospital in Dublin, Ireland. Approximately 500 cases of self-harm are treated annually. The study was approved by the hospital ethics committee.

Participants

Consecutive patients (aged 16–64 years) who presented acutely with self-harm by whatever means and had a lifetime history of at least one other episode were candidates for study inclusion and were approached in the A&E department. Exclusion criteria were: current history of addiction, substance misuse, psychosis or eating disorder; currently receiving psychotherapy; known history of dyslipidaemia; any treatment, diet or illness known to interfere with lipid or n-3 EFA metabolism; weight loss >10% over the previous 3 months; taking supplements containing n-3 EFAs or consuming fish more than once per week; changes to, or introduction of, psychotropic medication during the previous 6 weeks; unwillingness to participate in the study or living outside the greater Dublin area. During the course of the study patients continued to receive standard psychiatric care at either primary or specialised level and had changes to their psychotropic medication as prescribed by their treating agency. At the time of screening, all patients were free of intoxicants, had not suffered significant harm as a result of the self-harm act and had mental capacity. In addition to the outcome measures at baseline, participants completed the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–III–R, Axis II version (SCID–II, Reference First, Spitzer and GibbonFirst et al, 1997).

Sample size

Power analysis was carried out using nQuery Advisor, version 4 (Statistical Solutions, MA, USA). Using published data on completed suicide (Reference Zahl and HawtonZahl & Hawton, 2004) and recurrence of self-harm (Reference Kapur, Cooper and HiroehKapur et al, 2004), the number needed to detect a 20% difference (P<0.05) between groups would be approximately 1500 and 100 respectively, which was not feasible. However, to detect a 20% difference (P<0.05) in outcome measures using psychometric instruments (s.d. ranges 2–9), a total population of between 35 and 50 was estimated.

Outcome measures

Changes in the following psychological domains at study end point v. baseline were the outcome measures.

Depression

The 21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Reference Beck, Ward and MendelsonBeck et al, 1961) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1960) were used to assess depression.

Suicidality and aggression

The Overt Aggression Scale, Modified (OAS–M, Reference Coccaro, Harvey and Kupsaw-LawrenceCoccaro et al, 1991) was used. This is a clinician-administered semi-structured interview that was adapted from the OAS (Reference Yudofsky, Silver and JacksonYudofsky et al, 1986) for use with out-patients. It measures type, severity and frequency of aggressive behaviour. The three sub-scales measure aggression, irritability and suicidality on 4-point Likert scales. The instrument has satisfactory psychometric properties and is sensitive to change (Reference Coccaro, Harvey and Kupsaw-LawrenceCoccaro et al, 1991).

Impulsivity

This was assessed with Immediate and Delayed Memory Tasks (IMT/DMT; Reference Dougherty, Marsh and MathiasDougherty et al, 2002), which is a computer-based variant of the Continuous Performance Test (CPT) and is designed to objectively measure attention, memory and impulsivity. The IMT/DMT has satisfactory psychometric properties and is sensitive to change (Reference Dougherty, Marsh and MathiasDougherty et al, 2002).

Daily stresses

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS; Reference Cohen, Kamarck and MermelsteinCohen et al, 1983), a 14-item measure of the degree to which situations in one's life are appraised as stressful, was used to measure stress. Items are rated on a 5-point frequency scale ranging from 0, ‘never’, to 4, ‘very often’, for how often in the past month the person has experienced stress-related feelings and thoughts. A total perceived stress score is obtained by reversing the scoring on the positive items and summing responses across the 14 items. Higher scores indicate more stress. The instrument is widely used and has satisfactory psychometric properties.

The Daily Hassles and Uplifts Scale (DHUS; Reference Kanner, Coyne and SchaeferKanner et al, 1981) is a well-validated instrument which consists of a list of 18 items (such as children, parents, spouse, work, time for self and health) that can be sources of strain, stress and hassle. Items were clustered into five domains of sources of stress: family (parents, children, spouse, in-laws and other relatives); self (appearance, time for self and health); roles (work-related stress, relationships with co-workers and household jobs); social–environmental (housing, environment, security and socio-political situation); and financial. Sources of uplift were measured with a similar list of items, with a few modifications. Respondents were asked to indicate whether each item had been a source of pleasure or enjoyment for them during the past week. Items were clustered into the same five domains as above. For the purposes of analysis, total hassles scores were subtracted from total uplifts scores.

Intervention, randomisation and masking

Participants were prescribed four identical capsules of either active agent or placebo (both provided by Epax (formerly Pronova) AS, Lysaker, Norway), to be taken in the morning. Active capsules (EPAX 5500) contained 305 mg EPA and 227 mg DHA (total EPA plus DHA of 532 mg/capsule). The total dose equalled 2128 mg/day of EPA plus DHA. Placebo contained 99% corn oil and a 1% EPA/DHA mixture. This ensured a degree of equality in the incidence of ‘fishy breath’, the most frequent side-effect of taking active treatment. Adherence was encouraged by weekly telephone contact and ascertained from pill count. Participants who did not return or who missed appointments were deemed to be non-adherent. An independent colleague dispensed either active or placebo capsules according to a computer-generated list. The code was only revealed to the researchers once data collection was complete.

Statistical methods

Analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 12.0.1 for Windows) and the last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) method. Significance was set at 0.05 and all tests were two-tailed. Baseline data between groups were compared using the χ2-test for categorical variables and independent t-tests for psychometric tests. A repeated analysis of variance (ANOVA) with baseline rating scores entered as covariates was used to compare changes in psychopathology over time in the two groups. For psychometric data that were dichotomised, the χ2-test was used. Logistic regression was used to assess the independence of sub-scale scores.

RESULTS

Participants

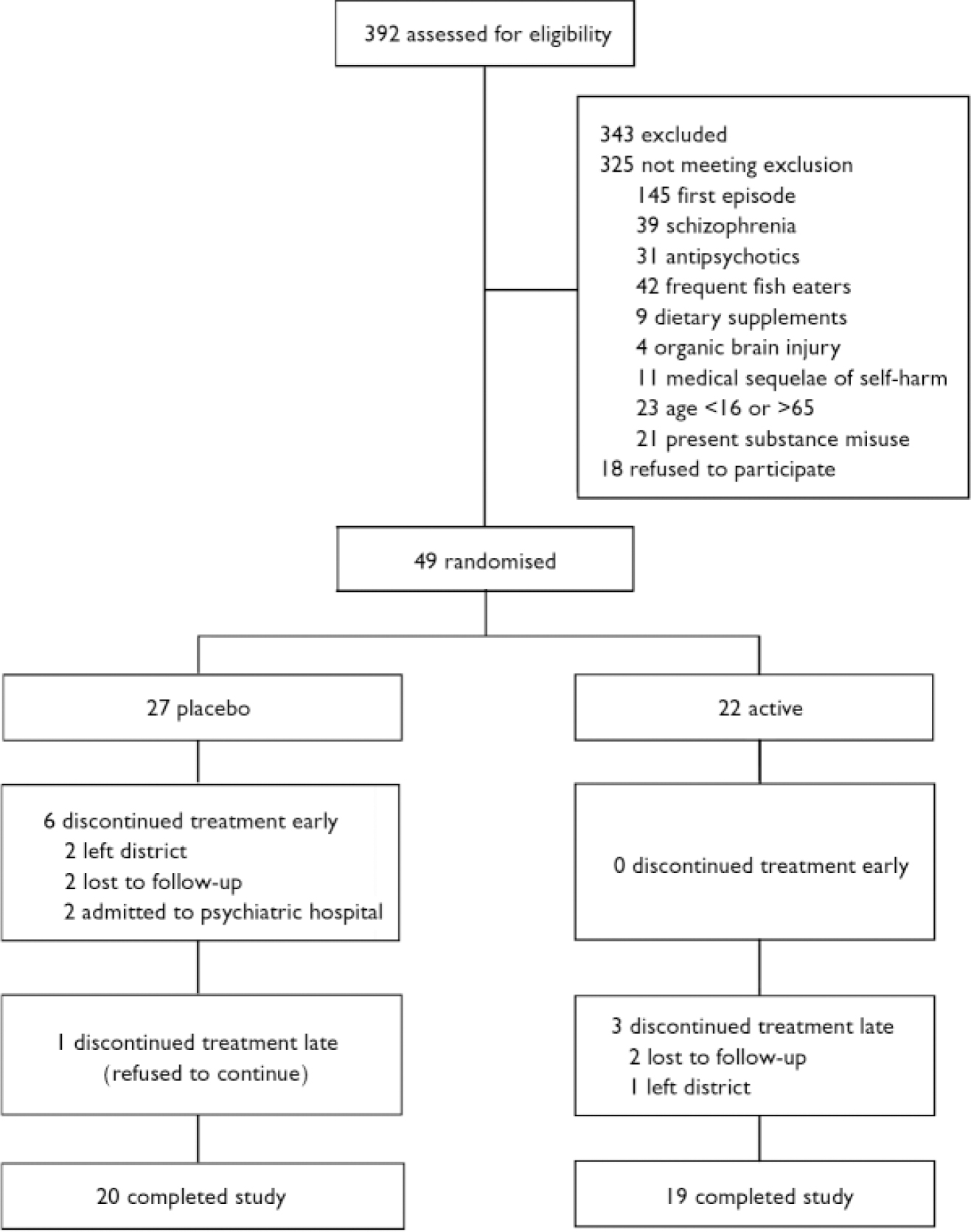

A total of 49 patients entered the study, with 27 randomised to placebo and 22 to n-3 EFA (Fig. 1). No patient withdrew consent during the study period. Baseline socio-demographic characteristics were similar in both groups, except for marital status: more patients were married in the n-3 EFA than the placebo group (Table 1). With the exception of the BDI (mean placebo group score 32.22, mean n-3 EFA group score 38.41, F=2.7, P=0.04), the mean baseline scores for all psychometric instruments were similar for both groups. The mean scores for all psychometric instruments were well in excess of published normative data.

Table 1 Baseline demographic and clinical data

| Variable | n-3 EFA group | Placebo group |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, n | ||

| Male | 7 | 10 |

| Female | 15 | 17 |

| Age, years: mean | 30.5 | 30.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 12 | 21 |

| Married | 7 | 0 |

| Divorced | 3 | 6* |

| Body mass index | 24.58 | 24.59 |

| Socio-economic group | ||

| I | 0 | 0 |

| II | 1 | 4 |

| III | 9 | 7 |

| IV | 5 | 8 |

| V | 7 | 8 |

| Employed, n (%) | 12 (54.5) | 12 (44.4) |

| Exercise,1 n (%) | 9 (40.9) | 11 (40.7) |

| Alcohol intake2 | ||

| Misuse | 11 | 9 |

| Dependance | 6 | 8 |

| Smoker,3 n (%) | 17 (77.3) | 20 (70.1) |

| Personality disorder, n (%) | 18 (81.8) | 22 (81.5) |

| Borderline | 17 (77.3) | 18 (66.7) |

| Paranoid | 7 (31.8) | 8 (29.6) |

| Psychotropic medication, n (%) | 13 (59.1) | 13 (55.6) |

Effects of n-3 EFA supplementation on psychopathology

Depression

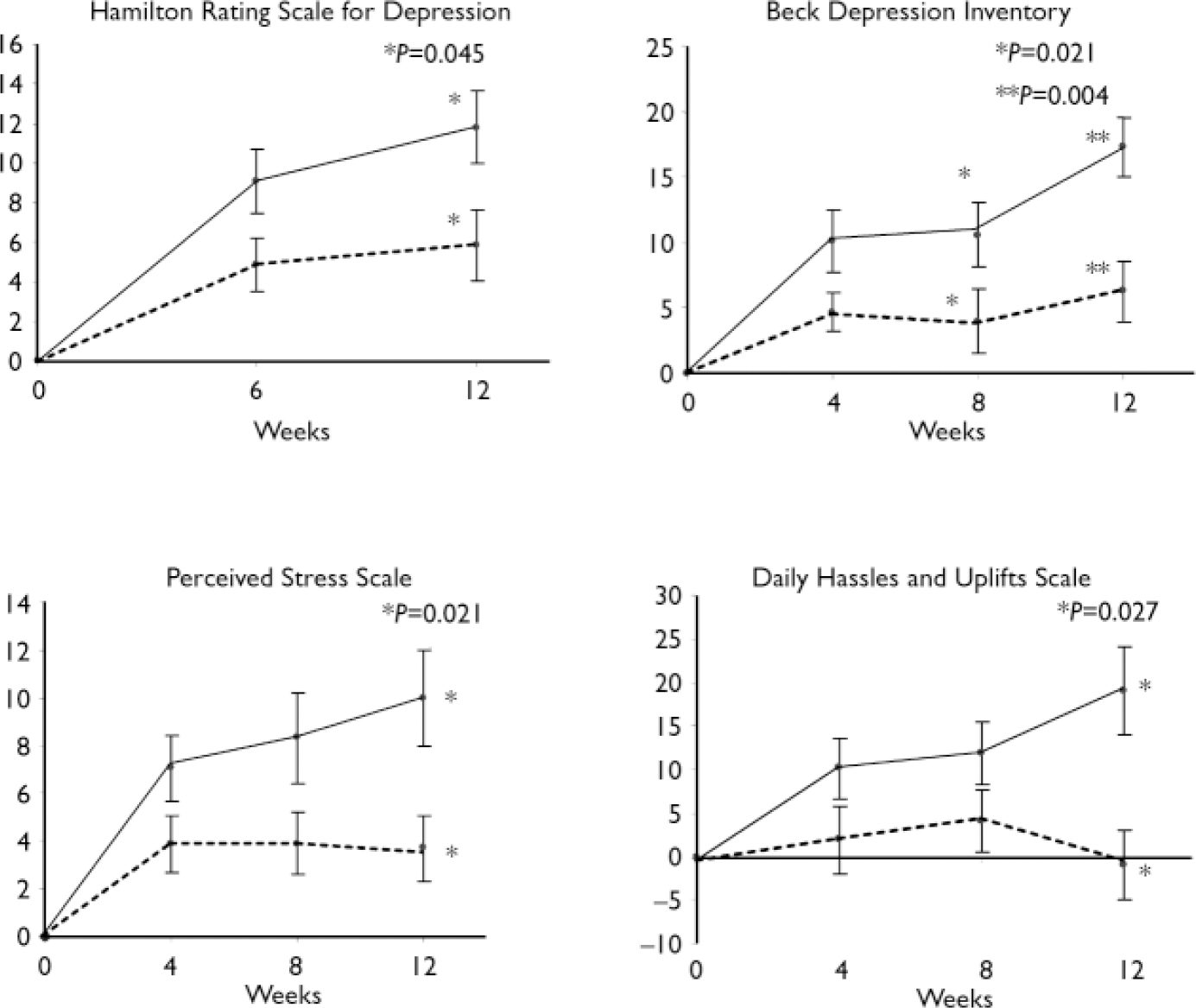

The baseline BDI scores were used as covariates in the subsequent statistical analysis (for all psychometric variables, baseline scores were entered as covariates). Table 2 shows the significant improvements in BDI scores at 12 weeks (P=0.004) in the n-3 EFA group. Moreover, more patients in the n-3 EFA group attained more than 50% (P=0.001) and 70% (P=0.001) reduction (response and remission respectively) in symptoms (Table 3). Similar data were observed for the HRSD. Figure 2 shows the improvements in depression scores at all measurements.

Table 2 Outcome variables for continuous data at study end point (12 weeks)1

| Variable | n-3 EFA group | Placebo group | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-varied mean | Change | 95% CI | Co-varied mean | Change | 95% CI | ||

| Beck Depression Inventory | 17.5 | 17.52 | 12.1-22.9 | 28.9 | 6.1 | 24.0-33.8 | 0.004 |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | 12.2 | 13.93 | 8.5-16.0 | 17.4 | 6.2 | 14.0-20.8 | 0.045 |

| Perceived Stress Scale | 19.9 | 9.65 | 16.4-23.4 | 25.6 | 4.0 | 22.3-28.7 | 0.021 |

| Daily Hassles and Uplifts Scale | 10.1 | 18.91 | 22.9-2.6 | -9.6 | -0.8 | 2.6-21.3 | 0.027 |

| Overt Aggression Scale | 10.3 | 10.57 | 6.7-13.8 | 14.5 | 6.4 | 11.3-17.7 | NS |

| Immediate Memory Task | 36.2 | 1.41 | 32.8-39.6 | 34.7 | 1.9 | 31.5-37.9 | NS |

| Delayed Memory Task | 37.0 | -1.13 | 32.5-40.4 | 32.5 | 3.5 | 28.2-36.5 | NS |

Table 3 Response and remission data

| Variable | n-3 EFA group | Placebo group | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | Absent | Present | ||

| Overt Aggression Scale — Suicidality > 1 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 19 | 0.02 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | |||||

| Response | 9 | 13 | 23 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Remission | 9 | 13 | 23 | 4 | 0.001 |

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | |||||

| Response | 10 | 11 | 14 | 7 | NS |

| Remission | 13 | 9 | 23 | 4 | 0.05 |

| Perceived Stress Scale | |||||

| Response | 13 | 9 | 25 | 2 | 0.006 |

| Remission | 19 | 3 | 25 | 2 | NS |

Suicidal ideation and self-harm

Taking a categorical value of zero to indicate no suicidal ideation and a value of 1 or more to indicate its presence (OAS–M suicidality sub-scale), more participants reported no suicidal ideation in the n-3 EFA group (n=14) than the placebo group (n=8, P=0.018), although the difference in the mean total OAS–M scores did not quite reach significance (P=0.057). Logistic regression indicated that neither the irritability and aggression sub-scales (both of which demonstrated no difference between the two groups) nor the depression scores had any effect on the suicidality sub-scale. There were no completed acts of suicide during the study period. Fourteen patients presented with self-harm episodes, 7 from the placebo and 7 from the n-3 EFA group (P=0.65); none was life threatening.

Fig. 1 Trial CONSORT diagram.

Impulsivity/aggression

No differences were observed at study end point in outcome measures (IMT/DMT, OAS–M total score) (Table 2).

Perception of daily stresses

Participants in the n-3 EFA group demonstrated a greater drop in mean PSS score at 12 weeks compared with those on placebo (P=0.021, Table 2). Significantly more patients attained a 50% drop (‘response’) in the n-3 EFA group at 12 weeks compared with placebo (P=0.006, Table 3). Significance was not reached for a 70% reduction (remission) – as only 5 patients (3 from the n-3 EFA group and 2 from the placebo group) attained this improvement in scores. Participants in the n-3 EFA group demonstrated a greater mean improvement in DHUS score at study end point compared with placebo (P=0.027). Any changes were independent of depression scores (logistic regression). Owing to the method used to calculate one mean DHUS score, response and remission data were not calculated. Figure 2 shows improvements in daily stress scores at all measurements.

Safety, tolerability and adherence

Four patients complained of mild gastric discomfort during the study and 3 of these were in the n-3 EFA group. A further 9 patients (2 placebo and 7 n-3 EFA) described a ‘fish-like taste’ from the capsules or ‘fish-like breath’ after consuming the capsules. No patients discontinued the study because of adverse events. There was a full adherence rate of 75.5% (37 patients). More patients in the n-3 EFA group were adherent: 4 in the n-3 EFA group were not fully adherent, compared with 8 in the placebo group (P=NS).

Fig. 2 Improvement in mean psychometric score during the course of the

study. Self-rated instruments were administered every 4 weeks and

observer-rated instruments every 6 weeks. ![]() , omega-3 essential fatty acid

supplementation; -----, placebo.

, omega-3 essential fatty acid

supplementation; -----, placebo.

Psychotropic medication

Almost two-thirds of patients were taking prescribed psychotropic medication (excluding anti-psychotics at baseline (Table 1). All were on antidepressants, with two-thirds taking prescribed benzodiazepines. During the trial period 5 participants in the placebo group were started on an anti-depressant and 2 had the dose of their anti-depressant increased, compared with 2 and 1 respectively in the n-3 EFA group (P=NS).

Subgroup analyses

Gender

Covarying for gender demonstrated no difference in any of the outcome parameters. Males had small but significantly higher baseline levels of alcohol intake, aggression (OAS–M) and antisocial personality disorder.

Personality disorder

There were equal proportions of patients with personality disorders in the two groups (>80%, Table 1). Many patients had more than one personality disorder according to SCID–II criteria. The most common personality disorders were borderline personality disorder (n=35) and paranoid personality disorder (n=15). The presence or absence of a personality disorder did not affect any treatment outcome (personality disorder entered as covariate in an ANCOVA). Similarly, excluding participants without personality disorder did not affect the strength of the findings, although caution needs to be exercised in analyses of such small subgroups.

DISCUSSION

Since the mechanisms of action of the n-3 EFAs are poorly understood and they have been reported to improve a wide range of psychopathologies, from type I symptoms in schizophrenia (Reference Peet and HorrobinPeet & Horrobin, 2002) to aggression in healthy people (Reference Hamazaki, Sawazaki and ItomuraHamazaki et al, 2001) we deliberately chose a population (recurrent self-harm) that would manifest a broad spectrum of psychological constructs and behaviours that could be measured for change reasonably quickly over time. Accordingly, our population, although not syndromally homogeneous, had scores on measures of depression, suicidality, aggression, daily stresses and impulsivity that indicated much greater in psychopathology than a healthy population. The high rates of Axis II disorder in the participants and levels of psychotropic prescribing also reflect this.

A principal driving force behind the improved functioning of the n-3 EFA group was the improvements in affect (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that scores were continuing to diverge from those of the placebo group at study end point, suggesting that continued improvement might have occurred with a longer period of supplementation. This is supported by data from clinical trials in which supplementation was for 16 weeks (Reference Hamazaki, Sawazaki and ItomuraHamazaki et al, 1996) or 20 weeks (Reference Gesch, Hammond and HampsonGesch et al, 2002). Although decreases in suicidality and daily stress perception were less dramatic than improvements in depression, they were independent of changes in depression score, indicating several different mechanisms of n-3 EFA action. However, the lack of change in aggression or impulsivity measures suggests a degree of specificity, although there are robust data from randomised controlled trials that n-3 EFAs reduce aggression (Reference Hamazaki, Sawazaki and ItomuraHamazaki et al, 1996; Reference Gesch, Hammond and HampsonGesch et al, 2002). Indeed, Zanarini & Frankenburg (Reference Zanarini and Frankenburg2003) reported a significant change in aggression (OAS–M score) after supplementation for only 4 weeks in people (n=30) with borderline personality disorder. For a discussion on the possible mechanism of action of n-3 EFAs at the molecular level, we refer to our accompanying paper (Reference Garland, Hallahan and McNamaraGarland et al, 2007, this issue).

It is important to stress that treatment as usual was carried out by the patient's treating psychiatrist/general practitioner, and the benefits seen were additional to normal care. The dosage of n-3 EFAs used is comparable to most other supplementation studies in psychiatric populations. The treatment was well tolerated, with only minimal side-effects, and for this population adherence was excellent (Reference SpiritoSpirito, 1996). The inclusion of a small amount of fish oil in the placebo preparation (with attendant ‘fish breath’ effects) made it unlikely that patients would have known which group they were in; this was confirmed at the end of the study (data not shown). Although 14 patients reported episodes of self-harm during the study, it was known a priori that the study was insufficiently powered to detect significant differences between groups.

Our accompanying paper details compositional deficits in a variety of n-3 EFAs in a different population of patients with self-harm (Reference Garland, Hallahan and McNamaraGarland et al, 2007, this issue). Taken together, the data suggest that reversal of an n-3 EFA deficit improves psychological status in such patients. The source of such deficits and the mechanism of improvement with supplementation remain a matter of speculation. Patients undergoing a period of life stress may be expected to consume different diets (Reference Oliver and WardleOliver & Wardle, 1999) and this may apply to fish consumption; alternatively deficits may be engendered by genomic or proteomic differences in metabolic pathways. We will examine this in future studies using blood samples taken from our patients.

Clearly there is now a mandate to proceed with a large-scale multicentre study with the primary end points of recurrence of self-harm and completed suicide, the principal targets of intervention.

Acknowledgements

B. H. received salary support from the Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.