Introduction

Multiple reports have identified hospitals as potential soft targets for terrorist attacks. Reference De Cauwer, Somville, Sabbe and Mortelmans1–Reference O’Reilly, Brohi, Shapira, Hammond and Cole4 The possibility of a terrorist attack on a hospital is not imaginary. Soft targets are defined as publicly accessible locations, civilian in nature, and usually with limited security measures in place. Reference De Cauwer, Somville, Sabbe and Mortelmans1 The public character and 24/7 accessibility of hospitals, as well as the vast amounts of materials, knowledge, patients, and personnel within, amplify the attraction of such facilities as a potential target for acts of terrorism. A terrorist attack against a hospital may cause a high number of casualties and can tarnish the perception of hospitals as safe havens. Reference De Cauwer, Somville, Sabbe and Mortelmans1,Reference Tin, Hart and GR5–Reference Finucane8

Hospitals may be affected by terrorist attacks in various ways. First, immediate (direct) consequences are related to the integrity and accessibility of hospital services, caused by structural damage to buildings or (medical) infrastructure. Large amounts of highly flammable materials, noxious gases, and radioactive materials held within hospitals can potentially make the effects of an attack worse. Second, there is a risk of injuries or fatalities among patients and personnel. Third, long-term (indirect) consequences may include financial losses to the institution, physical and psychological illness of patients and personnel, anxiety of personnel to return to the workplace, but also fear and lack of trust among patients to come (back) to the hospital. Finally, medical (transportation) devices such as ambulances may be hijacked or stolen from a hospital facility and used to carry out an attack. Reference De Cauwer, Somville, Sabbe and Mortelmans1,Reference Tavares7,Reference Jasani, Alfalasi, Cavaliere, Ciottone and Lawner9

Scientific data on the subject are limited. Medical literature predominantly covers the preparedness of hospitals for terrorist attacks that occur outside of the facility, focusing on injury patterns and surge capacity. Reference De Cauwer, Somville, Sabbe and Mortelmans1,Reference Finucane8 A study on terrorist attacks against health care facilities in general identified 901 attacks in 74 different countries from 1970 through 2018. There were 418 attacks against hospitals, but these attacks were not further specified. Reference Cavaliere, Alfalasi, Jasani, Ciottone and Lawner10 The remaining literature on the vulnerability of hospitals to terrorist attacks predominantly concerns case series, but their methodology is not clearly described. Reference Ganor and Wernli6,Reference Martin11 Therefore, the objective of this study was to identify and characterize all documented terrorist attacks against hospitals reported to the Global Terrorism Database (GTD; University of Maryland; College Park, Maryland USA) from 1970-2019.

Analyzing specific attack types and trends over time may help to improve preparedness for terrorist attacks and in mitigating their impact. Moreover, it may strengthen the foundations of counter-terrorism medicine, a rapidly growing sub-specialty of disaster medicine which aims to consolidate academic data on health care implications caused by terrorism. Reference Court, Edwards, Issa, Voskanyan and Ciottone12

Methods

Database

A database search of the GTD was performed by using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman13 The GTD is an open-source database containing over 200,000 global terrorism incidents that occurred in the period of January 1970 through December 2019. It is maintained by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) at the University of Maryland and is part of the US Department of Homeland Security’s Centers of Excellence (Washington, DC USA). 14

Definitions

The GTD defines a terrorist attack as follows: “the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.” 14 To be considered for inclusion in the GTD, the following three attributes must all be present:

-

1. The incident must be intentional;

-

2. The incident must entail some level of violence or immediate threat of violence; and

-

3. The perpetrators of the incidents must be sub-national actors.

Additionally, to be included in the database, two out of three of the following criteria must be present:

-

1. The act must be aimed at attaining a political, economic, religious, or social goal;

-

2. There must be evidence of an intention to coerce, intimidate, or convey some other message to a larger audience than the immediate victims; and/or

-

3. The action must be outside the context of legitimate warfare activities.

An extensive description of their origin and the data collection methodology can be found in the GTD codebook, which is available on the GTD website. 14,15

Search Strategy and Incident Selection

The full dataset of the GTD was downloaded and searched for terrorist attacks against hospitals. The year 2020 was not yet available at the time of the study. Due to loss of data, incidents from 1993 are not present in the online database. The efforts made to recover these incidents represent only 15% of estimated attacks. 14 A separate file with these recovered incidents has been made available by the GTD and was also searched for attacks on hospitals. A hospital was defined as “an institution that is built, staffed, and equipped for the diagnosis of disease; for the treatment, both medical and surgical, of the sick and the injured; and for their housing during this process.” 16 The following search terms were applied in the database: “hospital,” “emergency department,” “emergency unit,” “trauma center,” “doctor,” and “nurse.” Incidents were included if the aim of the attack was to target the hospital and/or if it took place inside the hospital or on its territory. Incidents in which the hospital was not the target were excluded, as were incidents that were reported twice and attacks on specialized clinics or primary health care centers. Cases in which there was insufficient information to determine whether the hospital was the target were further explored by reviewing grey literature found on search engines such as Google (Google Inc.; Mountain View, California USA). If information remained insufficient, the cases were subsequently excluded. Lastly, incidents coded as “Doubt Terrorism Proper” were also excluded. These are incidents in which there was doubt if they qualify as pure acts of terrorism. 15

Data Extraction

Data collected per incident included temporal factors, location (country, world region), intended target (hospital or specific person), attack and weapon type, successfulness of the attack, the number of casualties and/or hostages, and property damage. The successfulness of attacks is defined by the tangible effects of the attack and whether or not it took place. It is not defined by the (larger) goals of the perpetrators. It was also determined if the hospital was the primary or secondary target of the attack. Primary attacks are incidents in which the hospital is the main and intended target of the attack. Secondary attacks are defined as incidents in which an initial attack takes place elsewhere, followed by a deliberate follow-up attack on the hospital where patients from the initial attack are being treated. Incidents in which the hospital sustained collateral damage from an attack on another target were collected separately.

Data Analysis

Data extraction was done by the main researcher (NU). Each entry was then reviewed manually for inclusion or exclusion based on the incident description. The second author (DB) reviewed each entry, and in case of doubt or discrepancies, a third and fourth reviewer advised on the final decision (ET, AB). Data collection was completed on March 1, 2021. All collected data were exported into Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, Washington USA) and analyzed descriptively. Chi-squared tests were applied to evaluate the trends of incidents over time and the differences per world region, conducted with a significance level of P <.05. This study was approved by the medical-ethical review board of Maastricht University Medical Center (Maastricht, The Netherlands; 2021-2655).

Results

General Results

From 1970-2019, the GTD contained 454 incidents that fulfilled the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The attacks occurred in 61 countries on six continents. The majority of attacks were successful (n = 399; 87.9%). Suicide attacks occurred 50 (11.0%) times, 28 (6.2%) attacks lasted more than 24 hours, and 74 (16.3%) were part of a multiple incident attack.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flowchart.

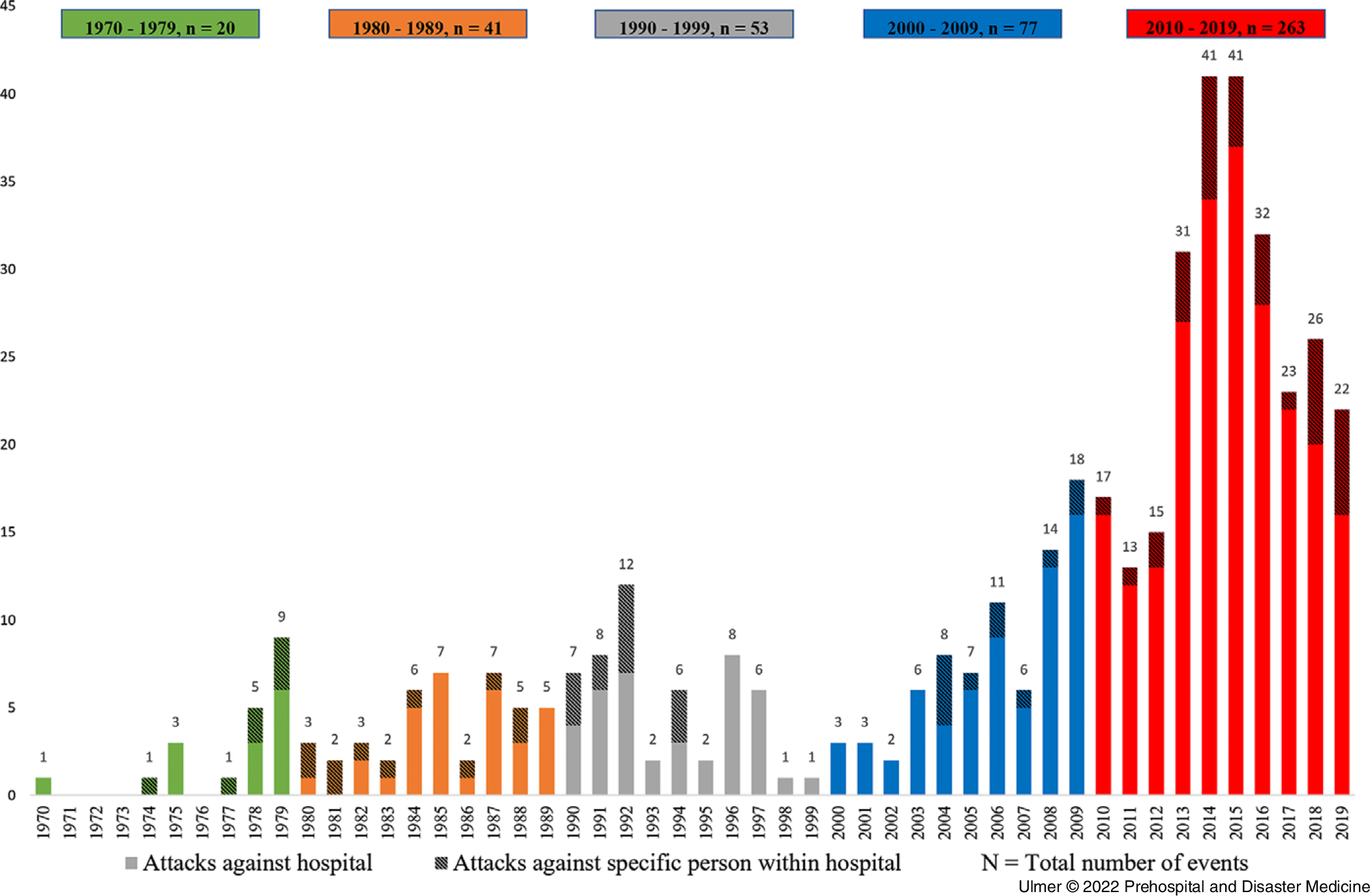

Events per Year

Figure 2 depicts the number of terrorist attacks against hospitals per year. An increasing trend was found from 2008 onwards, followed by a gradual decline from 2015-2019 with numbers still above the average (n = 10 per year) of the investigated time period. The number of incidents peaked in 2014 (n = 41) and 2015 (n = 41). A chi-square test to evaluate the difference in number of attacks per decade showed a significantly different distribution of number of attacks over decades: X 2 = 418.00; P <.001 (Appendix A; available online only). The difference in number of attacks in 1980-1989 compared with 1990-1999 was not significant: X 2 = 1.27; P =.26 (Appendix B; available online only).

Figure 2. Number of World-Wide Terrorist Attacks Against Hospitals per Year, 1970-2019.

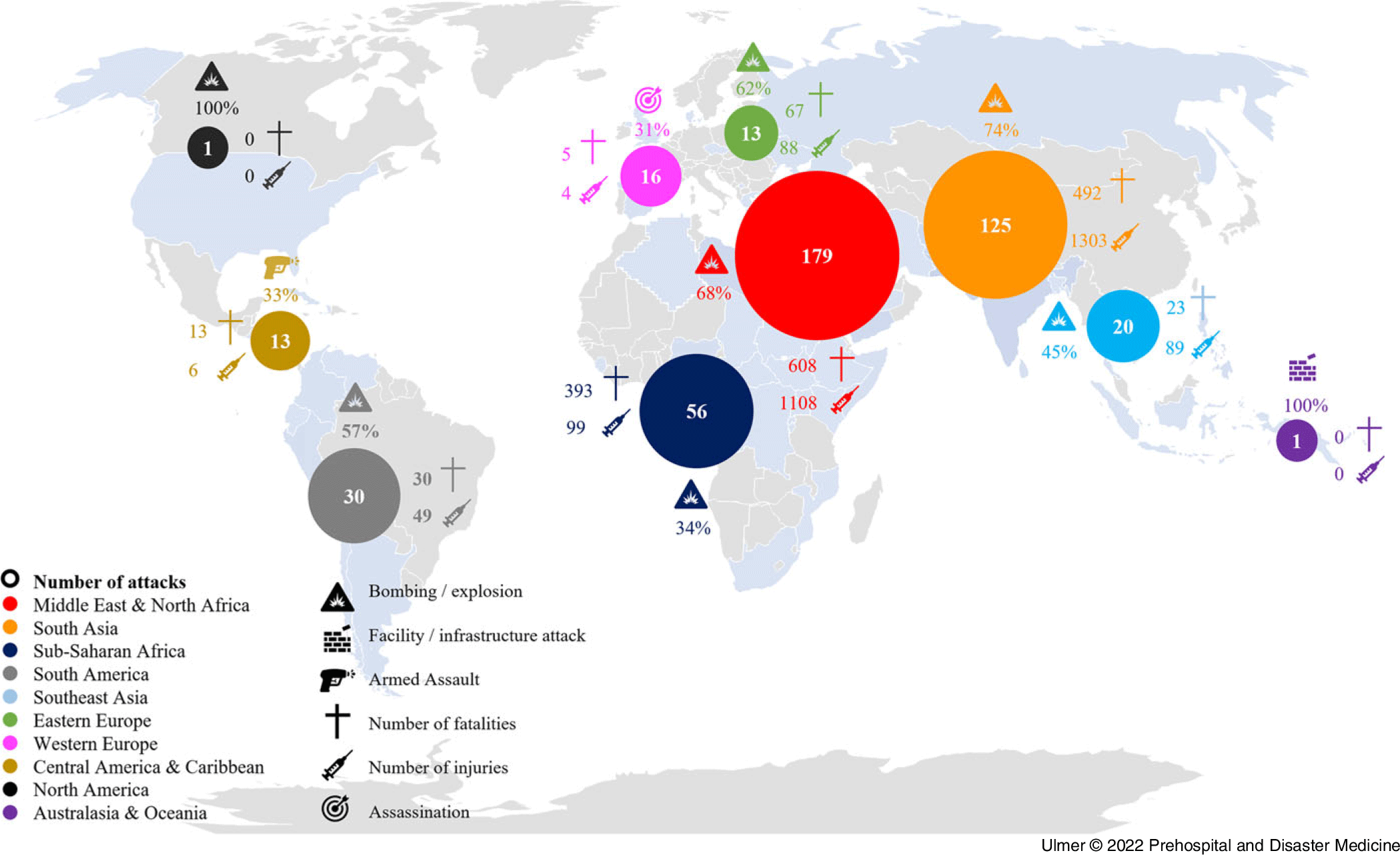

Events per Region

With 179 (39.4%) out of 454 attacks, the most frequently affected region of the world was the “Middle East & North Africa” (Figure 3). “South Asia” ranked second with 125 (27.5%) attacks, followed by “Sub-Saharan Africa” with 56 (12.3%) attacks. The remaining seven world regions comprised 94 (20.7%) of the reported attacks. Iraq (n = 47, 10.4%), Pakistan (n = 46, 10.1%), Yemen (n = 43, 9.5%), and India (n = 33, 7.3%) were the most affected countries. In 2014 and 2015, the years with the most attacks against hospitals, the most frequently hit countries were all situated in the “Middle East & North Africa.” In 2014, Libya experienced eight attacks and Iraq experienced seven. In 2015, twelve attacks were observed in Yemen, nine in Libya, and eight in Syria.

Figure 3. Infographic on Terrorist Attacks Against Hospitals per World Region, 1970-2019.

Attack Types, Weapon Types, and Property Damage

Bombings were the most frequently identified attack type (n = 270; 59.5%), followed by armed assaults (n = 77; 17.0%; Table 1). The predominant weapon types used to carry out the attacks were explosives (n = 275; 60.6%), which included explosives of unknown types (n = 78; 17.2%), projectiles such as rockets and mortars (n = 59; 13.0%), and vehicles (n = 47; 10.4%). Between world regions, a significant difference was found for the number of bombing/explosion attacks: X Reference Hojman, Rattan, Osgood, Yao and Bugaev2 = 273.10; P <.001 (Appendix C; available online only). Four world regions were not included in this statistical test as the number of attacks in those regions was low (Appendix D; available online only). More than one-half of the attacks (n = 260; 57.3%) sustained property damage to a certain extent, with an estimated value of less than one million American dollars (n = 133).

Table 1. Identified Attack Types for the Top Five Most Affected World Regions

Note: Please refer to Appendix D for data on “other” world regions.

Secondary Attacks and Collateral Damage

The GTD included three incidents where a hospital was the secondary target. The first event occurred in Iraq in 2004 where the primary attack was a bombing at a church. The remaining two secondary attacks took place in Pakistan in 2008 and 2013 where the primary attacks were aimed at a religious procession and a university bus, respectively. For all three incidents, the secondary attacks targeted the emergency department where patients from the primary attacks were being treated. In an additional 32 events, hospitals sustained collateral damage from attacks on other targets.

Casualties and Hostages

In total, 1,631 confirmed fatalities were registered in the GTD. Of these, 199 were perpetrators. A number of 2,746 people were injured, of which four were perpetrators (Table 2). The majority of attacks resulted in five or less people killed (n = 370; 81.5%) or wounded (n = 314; 69.2%), as shown in Table 3. Eleven incidents did not provide any information on the number of casualties, seven of which occurred before 1985. The deadliest year in this analysis was 2018 with 408 registered casualties. The deadliest attack identified occurred in 1994 in Rwanda when an armed assault on hospital patients and staff caused 170 fatalities. Hostages were taken in 41 (9.0%) attacks. The attack with the highest number of hostages occurred in Thailand in 2000 with 750 hostages held inside the hospital; all hostages were safely released.

Table 2. Number of Registered Casualties per World Region during Attacks Against Hospitals, 1970-2019

Table 3. Number of Attacks in which a Certain Number of People (n) Died or were Injured

Persons as Intended Targets

In 78 of the identified attacks against hospitals, a specific person or entity within the hospital was mentioned by the GTD as the intended target. Most attacks were aimed at medical personnel (n = 41; 52.6%), as shown in Table 4. The most common attack types were hostage takings/kidnappings (n = 29; 37.2%) and assassinations (n = 23; 29.5%). Firearms were the most frequently used weapons to execute these attacks (n = 48; 61.5%).

Table 4. Targeted Persons or Entities within the Hospital

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the threat of terrorist attacks against hospitals is real, especially in recent years and in world regions where internal conflicts are more prevalent. From 1970-2019, a total of 454 terrorist attacks against hospitals were identified in 61 countries, most of which occurred in the “Middle East & North Africa” and “South Asia,” but terrorist factions aim against hospitals globally. Bombings and explosions were the most common attack types, but armed assaults were also frequently noted, especially when specific persons were targeted. In total, the attacks resulted in 2,746 people injured and 1,631 fatalities.

Recently, the GTD was used for a study on terrorist attacks against health care facilities. From 1970 through 2018, 901 attacks were identified in 74 different countries. Forty-six percent (418/901) of these attacks were aimed at hospitals, but these incidents were not further specified. The majority of attacks occurred after 2001, which suggests that terrorist organizations are not only increasing their attacks against health care facilities, but also seem to become more comfortable targeting these types of facilities. Reference Cavaliere, Alfalasi, Jasani, Ciottone and Lawner10 A case study by Ganor and Wernli identified approximately 100 attacks in the period of 1970-2013. Reference Ganor and Wernli6 In comparison, this current study found more than double the number of attacks (n = 265) for the same study period. Direct comparison of the two studies is complicated, as the methodology of this particular study is not clearly described.

There was an increasing trend of terrorist attacks against hospitals from 2008 onwards, with 2014 and 2015 being peak years. The increase of incidents since 2008 may partially be attributed to the changing data collection efforts of the GTD. Consequently, the lower incidence of attacks in the earlier years may – at least in part – be due to under-reporting of data at that time. 15 It could also be hypothesized that the observed rise in terrorism incidents is associated with the United States 9/11 terror attacks in 2001, which is often considered as the start of the “new age” of terrorism. However, this hypothesis remains controversial. Reference De Cauwer, Somville, Sabbe and Mortelmans1,Reference DeLuca, Chai, Goralnick and Erickson17,Reference Smith and Zeigler18 The record number of attacks against hospitals in 2014 and 2015 was associated with the global terrorist violence peak in 2014, during which more than 16,800 attacks took place. This peak was most likely influenced by conflicts in key countries, such as Iraq, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. After 2015, the annual number of terrorist attacks gradually declined but remained above the long-term average. Reference Ritchie, Hassel, Appel and Roser19–Reference Miller21

Terrorism tends to be more common in countries with high levels of internal conflict (civil war, religious unrest). Reference Ritchie, Hassel, Appel and Roser19 This is reflected by the high number of terrorist attacks against hospitals in the “Middle East & North Africa” region as well as “South Asian” countries, where numerous (armed) conflicts took place in recent years. In comparison, western countries (including Europe and the United States) sustained fewer attacks against hospitals. In total, 29 attacks took place in Europe and only one in the United States. Some of these attacks can be linked to ethnical or secessionist conflicts. For example, three attacks were identified in Northern Ireland in 1980 and 1991 (during the Northern Ireland Conflict: 1968-1998). An additional four attacks in Ukraine (2014 - 2016) may have been related to the Donbas War that began in 2014. 22,23

Bombings and explosions were the most frequently identified attack and weapon type. This finding is in line with the analysis of 901 terrorist attacks against health care facilities, of which 53% concerned bombings. Reference Cavaliere, Alfalasi, Jasani, Ciottone and Lawner10 It however contradicts with some other reports, which estimated that suicide attacks and armed assaults were the most frequent attack types. This contradiction may largely be explained by selection bias in the published case series. Reference Ganor and Wernli6,Reference Martin11

Violent incidents against health care facilities, not solely acts of terrorism, are a major and on-going concern. This includes violence against patients, their relatives, and health care personnel. From the 78 attacks against specific persons within hospitals, more than one-half (52.6%) were aimed at medical personnel. Assassinations and hostage takings were the most common attack type. A report by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC; Geneva, Switzerland), focusing on violence against health care in situations of armed conflict, found patients to be slightly more prone to experience violence than health care personnel. Patients were more likely to get killed whereas health care personnel would mostly experience threats. 24,25

The findings of this suggest that hospital preparedness to deal with terrorism should predominantly focus on the prevention of bombing attacks and armed assaults as well as mitigating their impact. The exact implications are beyond the scope of this study, but offered are several general recommendations on target hardening and the mitigation of attacks. The first step is to acknowledge and accept that the threat does exist. The nature of the services provided, the 24/7 accessibility, and the multiple points of entry are only some of the reasons why hospitals will always remain potential soft targets. These aspects cannot be changed easily as it would ultimately alter the welcoming and public nature of hospitals. Nonetheless, it is important that hospitals improve their resilience to such (terrorist) threats, including the ability to maintain and/or restore their capabilities in these situations. One of the fundamental controversies that should be addressed is hospital security, both of the facility and of the individuals present inside. The “rings of protection” could help to determine different centripetal measures of safety, from the outside boundaries of the hospital to the inner critical areas. Restriction of access to specific (sensitive) areas and routine ID-checks can also be helpful to improve security. Reference O’Reilly, Brohi, Shapira, Hammond and Cole4,Reference Tavares7,Reference Tzu and Hesterman26 Furthermore, communication between hospital staff, departments, and authorities should be enhanced, as should the development of adequate facilities and availability of necessary equipment, such as decontamination rooms, radiation detection equipment, and protective clothing. Finally, security and disaster plans should be thoroughly reviewed and adapted. Once updated, they should be tested and routinely trained. Reference De Cauwer, Somville, Sabbe and Mortelmans1,Reference Tavares7,Reference Rogers27

The GTD identifies only three secondary attacks against hospitals. Nevertheless, recommendations are essential to minimize the effects of a potential second hit. Strict security procedures, such as the establishment of a secure perimeter and the restriction of hospital access, may be valuable preventative measures, especially when a hospital responds to an outside terrorist attack. Reference Leppäniemi, Shapira, Hammond and Cole28

Limitations

The GTD is the most comprehensive, up-to-date, open access, and reliable database of terrorist incidents. Reference Smith and Zeigler18 The database, and therefore this study, is subject to several limitations. The completeness of the data, especially in the earlier decades, is questionable. It is acknowledged by the GTD that at least in the first-half of the dataset, particularly in the period from 1970-1989, the number of terrorist incidents probably is under-estimated. 15,Reference Ritchie, Hassel, Appel and Roser19 It may in part explain the lower incidence of attacks against hospitals found in the earlier decades, in particular from 1970-1979.

Furthermore, the GTD relies on media publications for their information. Only high-quality sources are used, creating a possible selection bias. It is acknowledged that access to source materials has varied over time and that the availability of sources was at best when there was a short lag time in data collection. 15

The consequence of changing availability and access to data is that trends over time should be interpreted with caution. 15 Conversely, the GTD is a key source for global data on terrorism incidents and is the best available database of its kind. It is evaluated as the most complete record of terrorist attacks in recent decades. Reference Ritchie, Hassel, Appel and Roser19 Despite its uncertainties, the availability of the GTD’s data provided the opportunity to create an overview of attacks against hospitals over the years.

Another limitation of this study is the heterogeneity of hospitals as the definition of a hospital may differ between countries. This particular definition was chosen to create clear inclusion and exclusion criteria. It is however likely that some cases were missed in the analysis, either because they were not included in the GTD or because there was doubt about if the hospital was the target. In addition, this study specifically focused on terrorist attacks against hospitals and did not include primary care services or specialized health clinics. This may be a topic of future research.

Attempted but unsuccessful attacks are included in the GTD. However, threats, conspiracies, or the planning of attacks are not. Perpetrators had to be physically on their way to execute the attack to be included as an incident. Also, not included by the GTD but of growing importance is the execution of cyberterrorism against soft targets such as hospitals. These attacks have the potential to severely disrupt hospital networks, information systems, and access to medical devices. Reference Argaw, Bempong, Eshaya-Chauvin and Flahault29 Since the eruption of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, it was observed that hospitals appear to be even more prone to become targets of (cyber)terrorism. 30,Reference De Cauwer and Somville31

Conclusion

This analysis of the GTD, which identified 454 terrorist attacks against hospitals over a 50-year period, demonstrates that the threat is real, especially in recent years and in world regions where terrorism is more prevalent. Bombings and assaults are the most common used attack types. The findings of this study may help to create or further improve contingency plans for scenarios wherein a hospital becomes a target of terrorism.

Conflicts of interest

The author(s) declare none

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X22000012