In June 1933, Huddie Ledbetter, prisoner #19469 at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola, received welcome news. Pending the governor’s signature, the Louisiana Board of Pardons had agreed to commute his minimum sentence from six years to three, making him eligible to apply for parole. Ledbetter, forty-four years old, had been fighting for his freedom since he arrived at Angola on February 26, 1930. His intake papers described him as 5′ 7.5″ tall, 171 pounds, with black hair streaked with gray. He had “[g]ood teeth, medium ears, medium nose, black burn scar back of right hand, long cut scar right side of neck, cut scar left shoulder, sore scar right thigh.”1 His full sentence, if served, would run until February 6, 1940. For the first time since his incarceration, freedom seemed to be in sight.

A month later, John Lomax and his eighteen-year-old son, Alan, gathering material for an anthology of American folk music for Macmillan and the Library of Congress (eventually titled American Ballads and Folk Songs), arrived at Angola. The pair had recorded at three prisons in Texas before traveling east to Louisiana. They arrived on Sunday, July 16, 1933 and stayed for four days in hot, muggy weather; it rained both Sunday and Monday. Lomax, a portly, white sixty-five-year-old with a graduate degree from Harvard and a cigar frequently between his teeth, complained that they “found the fountains drier than they are in Texas” because at Angola, “Negro prisoners [were] not allowed to sing as they work,” thus limiting the Lomaxes’ ability to gather material. Yet “[o]ne man … almost made up for the deficiency.”2 At Camp A, they were introduced to “Huddie Ledbetter – called by his companions Lead Belly” who “was unique in knowing a very large number of tunes, all of which he sang effectively while he twanged his twelve-string guitar.” As an added bonus for the Lomaxes, Ledbetter, a seasoned performer, was well-versed in the type of songs they wanted to hear. “Alan and I were looking particularly for the song of the Negro laborer, the words of which sometimes reflect the tragedies of imprisonment, cold, hunger, heat, the injustice of the white man,” John Lomax wrote. “Fortunately for us and, as it turned out, fortunately for him, Lead Belly had been fond of this type of songs.”3 Ledbetter performed seven songs, some of them multiple times, as the Lomaxes recorded. These included “The Western Cowboy,” with a refrain of “cow cow yippie yippie yay”; “Frankie and Albert,” a ballad of love gone wrong; and “Goodnight, Irene,” an edgy waltz with a captivating tune:

Other songs included the up-tempo “Take a Whiff on Me,” a risqué song about cocaine that he said he learned from his father’s brother, Terrell; “You Can’t Lose-a-Me, Cholly,” which the Lomaxes described as a “ragtime strut” for dancing; and “Ella Speed,” another ballad of doomed love. Equipment problems meant that they caught only bits of some songs, including “Angola Blues,” which Ledbetter said he wrote while at the prison. It’s a lament about incarceration and being forced out of bed at 3:30 a.m. to work; about the woman he loved in Shreveport; and about the possibility of release.

The Lomaxes would later claim that the song was “a mélange of stanzas from many different ‘blues.’” But it spoke powerfully to Ledbetter’s situation and frustration, especially the final stanza:

As evidenced by audio archives in the Library of Congress, the recording quality in 1933 was poor.6 Lomax had been working with sound engineers to design and build a machine that would improve the quality of field recording, but it was not yet ready when he and Alan set out that summer. “The whole idea of using a phonograph to preserve authentic folk music was, in 1933 … radically different from the popular notion of recording,” wrote scholars Charles Wolfe and Kip Lornell. “Field recordings are not intended as commercial products, but as attempts at cultural preservation.”7 Setting out in June, the Lomaxes settled for a “cylinder model” dictating machine, “equipped with a spring motor,” from the Dictaphone Corporation.8 A year later, in 1934, they returned to Angola with the new machine, and the fidelity of these recordings makes it easy to imagine the astonishment the Lomaxes must have felt when they first heard Ledbetter’s powerful twelve-string guitar as it drove through the fast-paced tunes, accompanied by a voice that could caress with sweetness, howl in lament, and force the listener to pay attention. When Ledbetter played, he was in total charge, sometimes slapping his guitar in rhythm, sometimes contrasting the rhythmic movement of his feet and hands. In an age before amplifiers, his sound could – and eventually would – fill a concert hall.

In Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly, the Lomaxes claimed that after each song Ledbetter performed, “when Captain Reaux was not about,” he told them that he was eligible for parole and begged them to see if he could be paroled to work for them. Their book, published after the Lomaxes had begun to face criticism for their working arrangement with Ledbetter, alleged that it was Ledbetter who proposed the terms of employment: He would drive their car, cook their meals, wash their clothes, and be their man “as long as I live,” they quoted him as saying. Once he started his “old twelve-string to twanging” in any town in the United States, people would come running. “I’ll make you a lot of money,” they said he told them. “You needn’t give me none, ’cept a few nickels to send my woman.”9 Whether the passage is factual or not, the Lomaxes do seem to have investigated the possibility of getting Ledbetter released to them. In his 1947 autobiography, Adventures of a Ballad Hunter, John Lomax wrote, “He knew so many songs which he sang with restraint and sympathy that, accepting his story in full, I quite resolved to get him out of prison and take him along as a third member of our party.”10 After finishing their work at Angola, father and son drove to Baton Rouge to check the penitentiary records. “Often he had been in trouble with the law,” John Lomax reported in Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly. “Once he had been convicted for murder in Texas and given a thirty-year sentence; also he had been whipped twice in Angola for misconduct.”11 He couldn’t take Ledbetter with him, he told readers. “The picture kept coming to my mind of Alan and myself asleep by the roadside in the swamps of Louisiana and Mississippi with this particular black man on his cot near by, and the prospect did not look attractive.”12 Still, Lomax was intrigued by the performer and especially a song he recorded three times, “Goodnight, Irene.” On July 21, 1933, as he and Alan left Baton Rouge, Lomax wrote about it to his future wife, Ruby Terrill, Dean of Women at the University of Texas in Austin. “He sung us one song which I shall copyright as soon as I get to Washington,” he said, “and try to market in sheet music form.”13

Known as “The Farm,” the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola was then, and remains, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States. It reached its current size by the early 1920s: 18,000 acres (28 square miles) of land, a bit larger than Manhattan, and surrounded on three sides by the Mississippi River.14 Then, as now, Louisiana’s prison population was the racial inverse of the state’s population overall.15 According to the US census, in 1930 Louisiana had a total population of about 2.1 million people. Of these, 63 percent were identified as white, and 37 percent as Black.16 That year, 35 percent of those in Louisiana’s state and federal prisons were white, while 65 percent were Black.17 There were roughly 2,200 people incarcerated at the state penitentiary at Angola at the time of Ledbetter’s arrival, including 80 women. That total grew yearly,18 leading to overcrowding in the segregated, open-plan dormitories. “Beds have grown from one story – so to speak – to two story, and now three story beds are common,” the prison’s general manager reported to the state legislature in 1932.19

The penitentiary was built on the grounds of multiple plantations in West Feliciana Parish, including one named Angola, that had been owned by Isaac Franklin, a notorious domestic slave trafficker.20 His death in 1846 was “national news,” reported historian Joshua Rothman, whose 2021 book estimated Franklin’s worth to be “the modern equivalent of more than $435 million.” Nearly 70 percent of that value “was embodied in 636 people he enslaved. His obituaries never mentioned that fact, framing Franklin’s life as that of a self-made man.”21 With the abolition of slavery in 1865, farmers and plantation22 owners in Louisiana and throughout the South, including Franklin’s widow, Adelicia, found other ways to exploit Black labor. One involved a system known as sharecropping. “Sharecropping was the system of tenure designed for (and partly by) Negro freedmen in the aftermath of the Civil War,” wrote historian Jack Temple Kirby. It was a form of labor that bound entire families to landowners – nearly all of them white – through a form of rental in which the workers owned nothing, and instead were dependent on landowners for everything needed to farm, including “mules, horses, equipment or other capital,” he wrote. The landlord might provide “cabins, water, firewood, and other tangibles,” and in exchange supervised every aspect of the labor, often brutally. “Landlords’ control included extension of vital credit during much of the crop year,” and many “charged usurious interest rates.” Year after year, families might find themselves even farther behind than they had been the previous year, because “at settlement time,” sharecroppers, “especially” Black sharecroppers, “were generally obliged to accept without a question white bosses’ calculations both of commissary charges and cotton and other production,” Kirby wrote. “Share cropping was both a racial and a class system.”23 While itinerant workers could and did move from crop to crop, sharecropping families often became bound to a property because of debt: Attempting to leave without paying would result in criminal charges.24

Southern landowners as well as leaders in a range of non-agricultural industries also relied on the unpaid or low-paid labor of convicted prisoners. After emancipation, this was possible because of a clause in the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, ratified in 1865, that prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude “except as punishment for a crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”25 Prisoners – a majority of whom, after the war’s end, were Black – were forced to do the most dangerous and undesirable work, putting their lives at risk to extract coal, turpentine, lumber, iron ore, and other materials; clear fetid, snake-infested swampland; and labor in sawmills, brickyards, and endless fields of cotton, sugar cane, and corn. A flagrant disregard for the prisoners’ well-being led to extraordinarily high rates of death, disease, and disfigurement. If the work itself didn’t kill them, the absence of safe housing, nutritious food, clean water, or medical care, and the extreme brutality of white overseers might. If more laborers were needed for a particular task, more could be rounded up. As historian Matthew Mancini reported, quoting a gloating southern delegate to the National Prison Association’s 1883 meeting: “Before the war, we owned the negroes …. But these convicts, we don’t own ’em. One dies, get another.”26

This post-war exploitation of southern Black labor was not inevitable. For a period of roughly a decade, from 1867 to 1877, Congress intervened to stop the effort of white southerners to effectively reinstate slavery by imposing draconian laws known as “Black Codes,” and enforcing them through escalating white violence and terror. Congress passed the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which “divided the eleven Confederate states, except Tennessee, into five military districts under commanders empowered to employ the army to protect life and property,” wrote historian Eric Foner. The act “laid out the steps by which new state governments could be created and recognized by Congress – essentially the writing of new constitutions providing for manhood suffrage, their approval by a majority of registered voters, and ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.”27 In 1868, with southern states now under federal control, the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, acknowledging the full citizenship of “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” and their right to “due process of law” and “equal protection of the laws.” In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, acknowledging the right of all male citizens to vote, “regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”28 Black electoral involvement led to Black political leadership. “Sixteen African Americans served in Congress during Reconstruction,” wrote Foner. “[M]ore than 600 [served] in state legislatures, and hundreds more in local offices from sheriff to justice of the peace scattered across the South.” He noted, “Reconstruction governments established the South’s first state-funded public school systems, sought to strengthen the bargaining power of plantation labourers, made taxation more equitable, and outlawed racial discrimination in public transportation and accommodations. They also offered lavish aid to railroads and other enterprises in the hope of creating a ‘New South’ whose economic expansion would benefit Blacks and whites alike.”29

But whites in southern states fought hard to end this era of reform and “redeem” the South from shared governance. By 1877 – when John Lomax was about ten years old, and Wesley Ledbetter (Huddie’s father) was about seventeen – they succeeded, and the last federal troops were withdrawn following a political compromise that put a Republican president in the White House. Southern Democrats quickly moved to regain dominance, revising state constitutions to dismantle the economic, political, and social gains that had been made by Black southerners. By the 1890s, “the full imposition of the new system of white supremacy known as Jim Crow” had taken root.30 Virtually all of the 2,000 Black men who had “served in some kind of elective office” during the Reconstruction era were out of office by 1900, a point by which “Southern states disenfranchised black voters.” The term of the last Black congressman of this era ended in 1901.31 In Louisiana, the president of the 1898 state constitutional convention bragged about its ability to now “protect the purity of the ballot box, and to perpetuate the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon race in Louisiana.” Another speaker crowed, “We met here to establish the supremacy of the white race, and the white race constitutes the Democratic party of this State.”32 (Over the course of the twentieth century, notably, the platforms of the two major parties would significantly shift. As historian David Blight wrote in 2019, “the Republicans have not been the party of Lincoln on race relations for at least 60 years.”33)

The history of Reconstruction and its aftermath is important for two reasons. The first is that it establishes the legal systems that Huddie Ledbetter faced in both Texas and Louisiana. The second is that the South’s prison farms were built on the former plantations. These sites had exploited Black laborers first through enslavement and then through various forms of forced, coercive, and exploitive labor practices. This was the case with the Louisiana State Penitentiary, which took its name from one of those plantations. In 1880, three years after the federal troops left Louisiana, the widow of Isaac Franklin sold properties including Angola to a partnership headed by Tennessean Samuel L. James. Since 1869, James and his associates had enjoyed the exclusive right to manage Louisiana’s state prison system, meaning that they could exploit convict labor for their own benefit and also lease individuals out, for profit, to work on farms, plantations, levees, and other public and private interests. With their purchase of Franklin’s property, and in the absence, now, of federal oversight, they expanded these operations, launching what historian Mark Carleton described as “the most cynical, profit-oriented, and brutal prison regime.”34 Between 1870 and 1901, an estimated 3,000 prisoners leased under the system died.35

By the time Huddie Ledbetter was sentenced to Angola in 1930, convict leasing had been officially outlawed throughout the South, including Louisiana, although not eradicated,36 but the conditions under which the labor of Black men, women, and even children were exploited persisted. In 1901, Louisiana ended its contract with the James estate and resumed control over state prisoners, buying 8,000 acres of land from the family, including Angola and other plantations.37 Gradually, as the state built up its penitentiary’s infrastructure, it acquired additional land. The “profit motive” that had characterized the land’s use under convict leasing endured, noted Mark Carleton, “surviving for many years as the dominant principle in the state’s philosophy of prison management.”38 Over time, more land was purchased, and penitentiary structures were built on the site. In 1917, as a cost-cutting measure, “most of the professional guards” at Angola were fired, and their jobs were given “to ‘trusty’ convicts,” who enjoyed special privileges and carried weapons.39 In 1928, two years before Ledbetter’s incarceration, Louisiana’s prisons came under the authority of Huey P. Long, Jr., Louisiana’s governor from May 1928 to January 1932 (and US Senator from then until he was assassinated in 1935), who “looked upon the penitentiary simply as a state-operated business enterprise” that would, at minimum, be “self-supporting” – although it was not. Frequent flooding at the site and the onset of the Great Depression exacerbated problems.40

In June 1930, just four months after Ledbetter’s arrival, a state senate committee investigated Governor Long’s claim that Angola was “on a paying basis” – in other words, self-supporting. The committee’s report, released in July, found that the penitentiary’s financial affairs were in “a deplorable condition.” Further, the committee found evidence that forms of convict leasing were still operating. They charged that the current general manager, a Long appointee, had “entered into an illegal contract with John P. Burgin, Inc.,” a Pointe Coupee rice plantation operator, “for the cultivation of some twelve hundred acres of land” despite the prohibition against convict leasing.41 On August 25, 1930, a month after the report’s release, prisoners overseen by a man named Wallace W. Pecue staged an uprising at the rice farm. They locked themselves in a temporary wooden barracks to protest “brutal conditions, bad food, bad housing, long hours, and being obliged to work when ill without medical care.”42 Violence ensued, and, at Pecue’s order, a trusty shot and killed a nineteen-year-old prisoner. Pecue told the press that he found no grounds for the complaints; the men, he said, were just “too lazy to work.”43

The following spring, in April 1931, Governor Long appointed sixty-two-year-old Robert L. Himes, known as “Tighty,”44 to serve as general manager. The governor told the Baton Rouge Morning Advocate that he had “directed Mr. Himes to operate the penitentiary 100 per cent on the basis of efficiency.”45 Under this new leadership, the death rates escalated; between 1931 and 1935 they “were the highest since the days of the old convict-lease system,” according to historian Anthony J. Badger.46 In 1941, reporter Bernard Lewis “B.L.” Krebs investigated Angola on behalf of The Times-Picayune. The article is damning: “The machine politicians promised the taxpayers they would take the penitentiary ‘out of the red’ – and they did,” Krebs wrote. “But they didn’t tell the people of Louisiana that money they were making at the penitentiary … was coming from the blood and sweat and agony of 10,000 officially recorded floggings.” Krebs described thirty convicts whose official cause of death was “sunstroke,” when in fact they were “beaten in cane, rice and vegetable fields with five-foot clubs, redoubled grass ropes, blacksnake whips and in later years with the lashes of the captains.” He wrote of forty more prisoners shot dead, allegedly for trying to escape,47 and of many others who endured as many as sixty strikes of a whip at a time.48

Huddie Ledbetter, as the Lomaxes saw in the files, was among those disciplined. In their book, they were dismissive of what he had endured: “He was whipped twice for impudence,” they wrote, “but on the whole had as easy a time as a man can have at Angola.”49 A closer look at the records shows that it was Captain W.W. Pecue, who had overseen operations at the Burgin rice farm, who conducted both of the whippings. On November 21, 1931, he lashed Ledbetter ten times for “laziness.” On June 27, 1932, it was fifteen lashes for “impudence.” Pecue, born in 1875, was in his late fifties at the time of Ledbetter’s imprisonment. He attended school up to the eighth grade and had worked at Angola at least as far back as 1914.50 The instrument he likely used consisted of two belts of leather, each as thick as the sole of a shoe, roughly four inches wide and five feet long. At times, these straps would be dampened and dragged through sand, to increase the pain. Other prisoners would be ordered to hold the victim down, and his clothing would be pulled to expose a bare back or buttocks. “Three or four blows … could and generally did break the skin,” wrote Krebs. “Few prisoners failed to start screaming at the fifth or sixth blow.”51

That it was Pecue who did the beating offers some insight into Ledbetter’s placement within the prison. Ledbetter’s records state that on May 1, 1930, shortly after his arrival, he was made a “waiter” at Camp F. (Data from the previous year showed that Angola had nine camps, or quarters, labeled A to I. All but Camp D, the women’s camp, were segregated, and each housed between 140 and 225 people. There was also a receiving station and hospital, as well as road crews.)52 It seems likely that sometime after the uprising at the Burgin farm, Ledbetter was assigned to a road-building crew – a chain gang – overseen by Pecue. The 1932 penitentiary report listed four road camps: Pines, in Washington Parish (159 prisoners); Pine Grove, in St. Helena Parish (249 prisoners); Norwood, in East Feliciana Parish (159 prisoners); and Star Hill, in West Feliciana Parish (125 prisoners). “The Star Hill camp was organized in October [1931], after the Pointe Coupee rice crop had been harvested, the old rice camp being transformed and revamped into a road camp,” general manager Himes reported to the state legislature.53 As noted, in November 1931, Ledbetter was whipped for the first time by Pecue, although his change of assignment wasn’t noted in his record until February 8, 1932, when he was reported to be working on “R/C 5” (road crew 5) as a tailor.54 Pecue was overseeing this crew, 127 prisoners, as of April 1932.55 There were three deaths on this road crew in May: On May 14, Allen Julius died of typhoid fever; on May 23, Jeff Burns died of peritonitis, likely from an untreated injury; on May 25, W.O. Barney was shot and killed “while escaping.”56 Ledbetter was likely still with this crew on June 27, 1932, when he was again whipped by Pecue. Less than a month later, July 19, he was reassigned as a “Freemen’s waiter” at Camp A, serving the white camp personnel.

Captain James N. Reaux, the guard at Camp A where the Lomaxes first encountered Ledbetter in 1933 and again in 1934, and in whose presence Ledbetter did not dare speak freely, does not seem to have whipped him, although as Mark Carleton noted, “only ‘official punishments’ were recorded.”57 Reaux was, in fact, particularly brutal. Between 1930 and 1938 he was personally responsible for administering the greatest number of floggings at Angola: a total of 26,500 lashes. On sixty-two occasions, he whipped prisoners thirty-five times or more in a single session, according to Krebs’ analysis of the punishment records.58 The federal census of 1930 lists James N. Reaux as white and fifty-six years old, living with his wife and six children in a home on the penitentiary grounds.59 In 1933 alone, the year the Lomaxes first visited Angola, Captain Reaux’s record of flogging included 184 prisoners, according to Krebs. “They included one flogging of 50 lashes, two of 45 lashes, and one of 40 lashes for escaping; 25 lashes for ‘faking a telegram’; 25 for ‘refusing to go to work,’ and 15 for ‘sleeping after [w]rap-up.’”60

In the summer of 1934, John Lomax wrote to General Manager R.L. Himes: “Will you kindly let me know if Ledbetter, the 12 string Negro guitar player, is still in Angola?” A year had passed since his and Alan’s first visit, and Lomax had a “greatly improved machine”61 and wished to record more songs for the Library of Congress. Himes replied in the affirmative.62

The previous summer’s collecting, while not without its frustrations, had proven successful for Alan and John Lomax. Shortly after leaving Angola, they finally acquired the new recording machine. “The rear of the car was now stuffed with a 315-pound disc-cutting recorder, a vacuum tube amplifier, two 75-pound Edison batteries to power them, a generator for recharging the batteries, piles of aluminum and celluloid blank discs, a mixing board, a loudspeaker, a microphone, and boxes of replacement parts,” Alan Lomax’s biographer, John Szwed, wrote.63 The discs themselves were “twelve inches in diameter” and “hard to find anywhere in the United States.”64

The Lomaxes traveled to New Orleans, where John was briefly hospitalized for what Alan described as “a rather bad attack of malarial fever, which he contracted at the Louisiana state farm about two weeks ago.”65 After his release, Lomax looked up “Bertrand Cohn, a university classmate, who gave us cards to the New Orleans Athletic Club.”66 Cohn, an attorney whose wife’s family owned a lumber mill in the state,67 also “assigned” to the Lomaxes “a plainclothes man who will go with us tomorrow night into the jungles of Negroland where we hope to find some ballads and ballad music devoted to the seamy side of Negro life in the city,” John Lomax wrote.68 He was too ill to go, though, and, not surprisingly, the arrival of a white teenager and a posse of white detectives into the “dives and joints of New Orleans” led to a “constrained silence.” Invariably, Alan Lomax and the others, along with the bartender, “would be the only ones left in the hall.”69

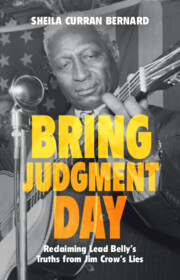

1.1 Camp A, Angola, July 1934. Huddie Ledbetter is in the foreground (no hat, striped shirt, at left and behind man with open shirt). Alan Lomax, photographer. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Lomax Collection, reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsc-00346.

An inability to gain trust from communities in which they wanted to record was part of the reason the Lomaxes were intrigued by the idea of working with Huddie Ledbetter. Some of the people they encountered were well aware that commercial record companies had been recruiting southern blues performers for roughly a decade. In New Orleans, for example, Alan Lomax encountered a “Billy Williams,” whom he described as “calculating” because Williams’ response, when asked to sing secular songs, was to wonder aloud what was in it for him.70 Others were uncomfortable or offended at being asked to sing material they considered “gutbucket” or, in the Lomaxes’ words, “sinful.” Some feared, for good reason, that cooperation with these white men from Washington would put themselves and their families at risk. A few, like “Blue,” a sharecropper they encountered on a plantation in Texas in 1933, bravely stepped forward to record a request for help from the newly inaugurated president, Franklin D. Roosevelt. In an article published the following year, Alan described the song, “Po’ Farmer,” which Blue claimed to have written and insisted that they record before he would agree to sing the song they requested, “Stagolee,” about a murderer. Alan noted Blue’s heightened awareness of the white plantation manager, keeping a close eye on the sharecroppers he’d gathered to sing, at night, for the Lomaxes. He reported “nervous merriment” among those listening, as Blue “sang of the tribulations of the Negro renter in the South, living and working under a system which is sometimes not far different from the peonage of Old Mexico.”71 The reference was to a form of debt bondage outlawed by Congress in 1867 but persistent throughout the South. As historian Pete Daniel noted, “the federal government acknowledged that the labyrinth of local customs and laws which bound men in debt” in the decades that followed “was peonage,” but federal efforts to address the injustice were slow.72 Blue’s song decried conditions that kept workers in rags, hunched over as they picked cotton, and in debt to the landowner’s commissary. Forty years later, in the 1970s, Alan wrote that recording Blue singing “Po’ Farmer” had “totally changed” his life,73 yet its import was minimized in his 1935 article, and the song was not included in American Ballads and Folk Songs. It did receive mention in the book’s introduction: “Only this summer [1933] a Negro on a large cotton plantation we visited, misunderstanding our request for ‘made-up’ songs, composed a satire on the overseer,” the Lomaxes wrote. “This song, ‘Po’ Farmer,’ was greeted with shouts of approval when the author sang it that night at the plantation schoolhouse. It is the type of song that may grow into a genuine ballad.”74

Research for American Ballads and Folk Songs, submitted in manuscript form to Macmillan in October 1933,75 meant that John and Alan Lomax had journeyed “in a Ford car more than 15,000 miles”76 through Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Kentucky. Two months later, eager to continue field recording, they submitted a proposal to the Carnegie Corporation, arguing that further collection of African American musical traditions had to be done before it was too late. “The Negro in the South is the target for such complex influences that it is hard to find genuine folk singing,” they wrote. They blamed Black political leadership, religious leaders, “prosperous members of the community,” and “the radio with its flood of jazz, created in tearooms for the benefit of city-dwelling whites” for “killing the best and most genuine Negro folk songs.”77 Their proposal was successful, as was another, more modest request to the Rockefeller Foundation. “In the end,” wrote Lomax biographer Nolan Porterfield, “the Carnegie grant … paid for a substantial part of Lomax’s travel expenses, while the Rockefeller money went for recording accessories and rebuilding the back of a brand-new blue Ford sedan.”78 And so, in July 1934, they were ready to return to Angola.

Despite all of his efforts, Huddie Ledbetter was still incarcerated in July 1934. More than a year had passed since the Board of Pardons approved the commutation of his sentence, but the governor’s signature was still pending. Learning that the Lomaxes would be returning, Ledbetter began to update an appeal he had mailed to Louisiana’s previous governor, Huey Long, in the fall of 1931. Long had apparently found the missive amusing, because it reached the press: “Prisoner Asks His Freedom in Poetic Epistle.”

New Orleans, Oct. 9. – Huddie Ledbetter, serving a sentence of from 6 to 10 years for shooting Dick Ellet at Shreveport, sought his freedom in the following epistle to Gov. Huey P. Long:

The following day, an article about the poem also appeared in The Times-Picayune. It quoted Lawrence A. Sauer, Secretary of the Board of Pardons, who explained that Ledbetter’s poetic appeal “could not be considered because it was not advertised and was irregular in other respects.”80 It is not clear why it took so long, but in May 1933, about two months before the Lomaxes’ first visit, Huddie Ledbetter successfully submitted a formal application, number 6633, for “commutation of sentence.” It was this request that reached the Board of Pardons and was approved.81 By then, it was the signature of fifty-year-old Oscar Kelly “O.K.” Allen, Louisiana’s latest governor, that Ledbetter needed. In the meantime, Ledbetter, as required and in anticipation of the governor’s signature, posted a public notice in The Shreveport Times. It ran on July 18 and July 28, 1933: “I am applying for parole. HUDDIE LEDBETTER.”82

By November 1933, when there was no further action, Ledbetter wrote a note to Governor Allen, enclosing a version of the poem he’d sent to Governor Long. Whether Allen received the letter or not is unclear, because it was the penitentiary’s general manager, R.L. Himes, who responded, noting that, because Ledbetter was a “second termer,” he could “not be reprieved.” Unless his sentence was reduced (commuted), he would not be eligible “to parole” until February 1936, Himes wrote, reminding Ledbetter – as he already knew – that “[t]he only other relief than this is through the Board of Pardons.”83

On December 8, Ledbetter, or someone assisting him, typed a response to Himes, arguing that he was not a second timer. “I am certain you have been misinformed or an error was made in looking up my record. I have never been in prison before anywhere. I have never served a jail sentence anywhere. I have been arrested for fighting once but only got a fine of thirty dollars for it.” He asked Himes to “straighten this up” for him, and then pointed out, correctly, that he had “already made a time cut on the June [Parole] Board but up until this date it hasn’t been signed by the Governor.” Did Himes “think it advisable to try the board again?”84

Ledbetter may have hoped that Louisiana prison officials did not know about his incarceration in Texas under the alias “Walter Boyd,” but they did. Three months after he arrived at Angola, a fellow prisoner informed on him. Following up, an Angola prison captain wrote to the warden in Texas for details. “There is a prisoner in this La. State pen. Angola, La., under an assume name,” the captain typed. “This man is known by another prisoner here to be Walter Boyd. Escaped from Texas Pen. Between 1919 and 1921, But he thinks it was in 1920.” The Louisiana captain asked if Texas had “any record on a party by this name. If so you may come out and look this man over. This prisoner states that Boyte has about 40 or 50 years to do in Texas.” By hand, the captain added: “PS. This man is a Negro, Walter Boyd. He is a great dancer and guitar picker.”85 Texas responded on May 12, 1930: “You are respectfully advised that our prisoner #42738, Walter Boyd is possibly the man that you have. He was received into the Texas Prison System in 1918 with a thirty (30) year sentence for Murder, but was pardoned on Jan. 16, 1925.”86 The letter noted that “Boyd” was not wanted by the Texas institution.

Now, more than three years later, Himes responded to Ledbetter’s note from December 8, 1933: “Dear Huddie: It’s unusual for these finger prints to make a mistake. I wish you would try real hard to remember and see if you remember being an inmate of the Texas State Penitentiary in 1918. Let me know about that. You were under the name Walter Boyd at that time.”87 Still Ledbetter persisted, handwriting a note to Himes dated March 2, 1934, “pleading for freedom.” He said his fingerprints had only been taken once, and added, truthfully, that “Governor Pat M Neff pardon me with a full pardon.” He had already been at Angola for four years, he wrote. He asked if Himes would please clear up his record and let him go back to his “happy home.”88 On March 13, Himes sent a brief response: “Last June the Board of Pardons recommended a change in your sentence from 6 to 10 years to 3 to 10 years. The Governor has not signed.” In what must have been a frustrating addition, because this was where the correspondence began, Himes closed by suggesting that Ledbetter “write your letters to the Governor.”89

Huddie Ledbetter was growing desperate. On April 2, 1934, he sent another typed note to Himes, reminding him that the governor “had not signed the recommendation of the Board of Pardons.” He said that he would “appreciate very much” if Himes would let him know “what has been done toward giving me my freedom.” Ledbetter seems to have also been calculating how much of his sentence would be left even without the pardon, if good time credits were awarded. “I have only four months to serve before my time is up,” he told Himes, “and will appreciate anything you can do to help me gain my freedom.” But Himes was done corresponding. Instead, he made a note on the letter: “Do not answer. 3/13/34, suggested he write Governor.”90

Still, Himes decided to investigate Ledbetter’s claim that he had been pardoned in Texas, because the information had apparently not made it into his Louisiana State Penitentiary record, and Himes may not have seen the 1930 correspondence. On June 21, 1934, the same day that Himes wrote to John Lomax to let him know that Ledbetter was still at Camp A, Himes sent an inquiry to the Texas Prison System’s Bureau of Records and Identification.91 In reply, he was informed that “an examination of the records reveals that he [Boyd/Ledbetter] was granted a full pardon on January 21st, 1925 by Governor Pat M. Neff by proclamation #1814 dated January 16th, 1925.”92 Walter Boyd’s Texas Prison System “Certificate of Conduct” noted that he received a “FULL PARDON” (capitalized in the original) and, below that, added the words, “CLEAR RECORD.”93 With this information, Himes or an assistant updated Ledbetter’s Louisiana penitentiary record. A typed version, dated June 27, 1934, noted the punishments at Angola and Ledbetter’s work and camp assignments. It also noted: “He served a term in Texas for murder; was pardoned.” Below that is typed, “D.G.T. [double good time] would have released him June 26, 1934. Fact of his pardon has just been ascertained. In the ordinary course, he will come up July 15th for consideration for discharge August 1st.”94

Ledbetter’s advocacy for himself had paid off. By the summer of 1934, with or without the governor’s signature, and with or without a second visit by the Lomaxes, Ledbetter was due to be released.

John and Alan Lomax returned to Angola on July 1, 1934. Now forty-five, knowing that his release should be imminent but not leaving anything to chance, Ledbetter was once again “ready to sing in his strong, resonant voice; ready to play marvelously his old twelve-string guitar,” the Lomaxes reported in Negro Folk Songs as Sung by Lead Belly.95 Ledbetter began by launching into an astounding performance of “Mister Tom Hughes’ Town,” after which, clearly satisfied, he shouted, “Lord!” He was then recorded, speaking clearly and with none of the dialect ascribed to him later, that the song “has been sung by Huddie Ledbetter, sometimes known as Lead Belly, on the farm at Angola, Louisiana in Camp A, for the Library of Congress in Washington.” Later, following a recording of “The Western Cowboy,” Ledbetter announced: “This song was composed by Huddie Lead Belly, Camp A, under Captain Reaux,” adding that he was from Mooringsport, Louisiana and was the “Twelve-String King.” Twice more during this July visit, Ledbetter made sure that his name accompanied a song, including a lengthy rendition of “Blind Lemon Blues.” When he was done playing, he said, “This song was composed by Huddie Ledbetter in memory of Blind Lemon of Dallas, Texas, with whom he used to work …. The song has been sung by Huddie Ledbetter for the Library of Congress in Washington.” Following “Matchbox Blues,” he said: “This song was played and sung by Huddie Ledbetter, of camp number one, Angola Farm, the state penitentiary of Louisiana … otherwise known as Lead Belly, for the Library of Congress in Washington.” The next song was a driving, fast-paced performance of “Midnight Special,” followed by a few starts and stops on “Goodnight, Irene.” In all, he sang and recorded fourteen songs that day.96

The energy of Ledbetter’s performances is not conveyed by the Lomaxes’ description of them in their book. They wrote: “All that Sunday he sang for us in the rain – a pitiful-looking figure in bedraggled, ragged stripes – while the drizzle formed in drops and ran down his face.”97 The book collapsed the two Angola visits, and this is likely an example of it. During the 1933 visit, it rained during two of the four days they recorded, and it seems clear from correspondence that they did not meet Ledbetter on their first day, a Sunday. In 1934, they did record on a Sunday, and it wasn’t raining. The Lomaxes wrote that “at every pause” during this second visit, Ledbetter was “urging [them] to help him win his freedom.” After “Goodnight, Irene,” the seventh of the fourteen songs they recorded, they said that Ledbetter “sang a petition – a crude version of his own composition – to Governor O.K. Allen to pardon him, telling us that he had once sung a similar song to Governor Pat Neff of Texas.”98 The lyrics echoed the poem he’d sent to Governor Long in 1931, and then revised and tried to get to Governor Allen in 1933:

In the book, John Lomax took credit for suggesting the recording, saying that the “power of his singing, his earnestly repeated appeals, his plight” finally “moved” him to offer to record the plea. This seems unlikely; it’s clear from the lyrics that Ledbetter revised the song in anticipation of the chance to record it. He appealed by name to the white men in charge of his fate – not only the governor, but also the general manager, the warden, and the lieutenant governor. He also made it clear that he had been paying attention to newspaper accounts about Himes releasing prisoners to maintain prison finances and “relieve severe crowding.”99

After additional verses, Ledbetter ended the song with a dramatic flourish:

Had you Governor O.K. Allen, like you got me,

He slowed the pace and stretched out the phrasing:

I’d wake up in de morning,

He then strummed the guitar a few times, calling the listener to attention before finishing:

Let you out on reprieve.100

The Lomaxes reportedly brought the aluminum disc to the governor’s office in Baton Rouge a day later, intent on playing it for him. Governor Allen was in a meeting with Senator Huey Long, John Lomax wrote in the book, and so he left the record with a secretary, “who promised to play it for his chief.”101 Whether this happened or not is unknown; it seems unlikely that the governor’s office had the means to play the disc. Undeterred, Lomax implied cause-and-effect as he jumped to the next sentence: “On August 1, Lead Belly was across the Mississippi River and headed for Shreveport. In a bag he carried a carefully folded document. Governor Allen’s pardon had come.” An asterisk follows this, and small type at the bottom of the page reads, “*General Manager Hymes [sic] has since written to me that Lead Belly’s pardon was due to his ‘good time.’”102 In fact, Himes made it clear that Ledbetter had not been pardoned at all, although the book repeatedly says he was, referring to “Lead Belly’s pardon papers” and the “‘Pardon Songs,’ successful appeals for freedom addressed to Governor Pat Neff of Texas and Governor O.K. Allen of Louisiana.”103

The real story is simpler. About three weeks after the Lomaxes’ second visit to Angola, on July 1, 1934, the governor finally turned his attention to the commutation recommendations. As historian Marianne Fisher-Giorlando wrote, “Ledbetter’s was one of six commutations signed on July 20, 1934, and one of 179 in the whole year, for crimes including murder, manslaughter, shooting at a dwelling, and carnal knowledge – such commutations were common enough to be essentially routine.”104 But thirteen months had passed since the Board of Pardons recommended commutation, and, by the summer of 1934, Ledbetter didn’t need to seek parole. Because of his own successful efforts to correct his record, Ledbetter’s good time allowance alone, under Louisiana Act 311 of 1926105(as Himes noted in his file), could have freed him by June 26, 1934. Ledbetter “was not allowed all of his extra good time, and was [therefore] not discharged until August 1, 1934,” Himes clarified.106 This good time release was provisional, however, a fact that Himes shared with John Lomax in a letter. Should Huddie Ledbetter again be committed to the penitentiary in Louisiana, Himes wrote, Ledbetter “would be required to serve out the balance of 5 years, 6 months, 25 days” before beginning to serve the new sentence.107

Yet, throughout their time together, John Lomax would continue to suggest that he had played a role in Ledbetter’s “pardon.” It made for a good story, one that reflected benevolently on Lomax and, by extension, the judicial system. It also created grounds by which John Lomax could expect gratitude from the performer, and public repetition of the story could assuage criticism that he was exploiting him. In the months to come, however, as John Lomax felt his control over Ledbetter waning, his insistence on taking credit for Ledbetter’s freedom would morph into a gnawing sense of responsibility for a man he had come to dislike, and even fear.

For now, though, it was gratitude that Lomax planned to use to his advantage. On September 24, 1934, less than two months after his release from Angola, Huddie Ledbetter met up with John Lomax at the hotel in Marshall, Texas, ready to spend much of the next three months on the road together, gathering folk songs. However much Lomax might previously have played up his concerns about Ledbetter and his knife, he had no such qualms now. “Ledbetter is here and we are off,” he wrote to Ruby Terrill, now Mrs. John Lomax. “Don’t be uneasy. He thinks I freed him. He will probably be of much help.”108