Em um amplo salão, um dos maiores deste concelho, dançavam cerca de 40 pares; e o numero das damas que assistiam ao baile, entre senhoras e meninas, todas mais ou menos elegantemente trajadas, exedia de 50, o que é raríssimo, para não dizer singular, nos bailes das aldêas deste concelho. Succederam-se alternadamente, e ao som da orchestra da distincta musica do extincto 2.° batalhão, as velhas contradanças, as agitadas polkas, as vertiginosas walsas, as cadenciadas varsovianas, e os clássicos mandós indianos.

(In an ample salon, one of the largest in this district, danced about 40 pairs; and the number of ladies who participated in the ball, including matrons and young girls, each one elegantly dressed, exceeded 50—a situation most rare, if not to say singular, at the balls of the villages of this district. At the sound of the orchestra of the distinct music of the former second battalion, there followed one aftenr the other old contradances, frenetic polkas, vertiginous waltzes, swaying varsoviennes, and classic Indian mandos.)

(O Ultramar, 8 May 1884)

Introduction

In 1884, the journal O Ultramar reported from the wedding of the daughter of Senhor Antonio Maria Xavier Rodrigues of Margao, South Goa, noting that, at the ball that followed the ecclesiastical proceedings and that lasted until six in the morning, about 40 couples at any given time were dancing to the music of a live orchestra.Footnote 1 The dances described therein were those prevalent worldwide wherever Europeans had settled and intermingled with other peoples in the course of creating their empires. But, within the gamut of European-derived social dances, from the ‘old’ contradances to the newer, ‘frenetic polkas’ and ‘vertiginous waltzes’, an item stands out by dint of its specificity to Goa: the ‘classic Indian mando’. What kind of a dance is this, and what can it tell us about Goa and its relationship to India on the one hand and Europe on the other?

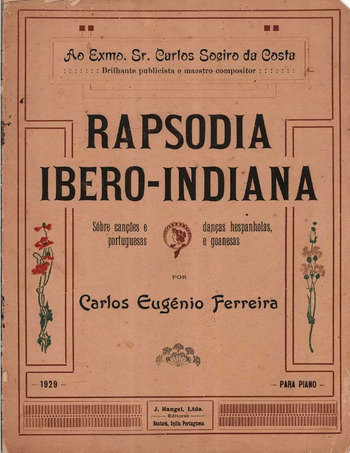

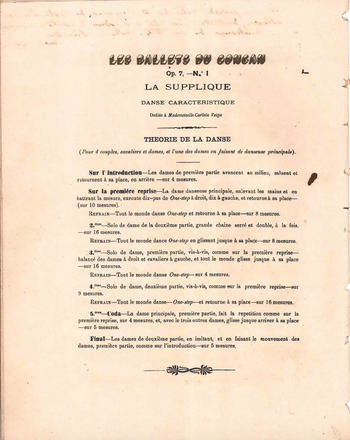

From the 1860s onwards, the word mando started to appear within descriptions of Goa's music-and-dance culture in Portuguese-language ephemera. In these attestations, mando names a music-and-dance genre enjoyed by the Indo-Portuguese elites in specific sociocultural contexts, particularly wedding ceremonies. From 1890 onwards, mando lyrics, composed in a baroque Konkani striated with Sanskritized and Latinate lexis, accompanied by musical scores,Footnote 2 were being published by local presses. By 1902, the mando and associated genres were being idiosyncratically re-elaborated by one Carlos Eugénio Ferreira of Corjuém, North Goa. Through the first quarter of the new century, he produced piano compositions with dance instructions and lyrics in French, Portuguese, and Konkani, including the extravagantly entitled Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana (neo-Latin, ‘Ibero-Indian Rhapsody’) (Figure 1).Footnote 3

Figure 1. Carlos Eugénio Ferreira, Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana, cover.

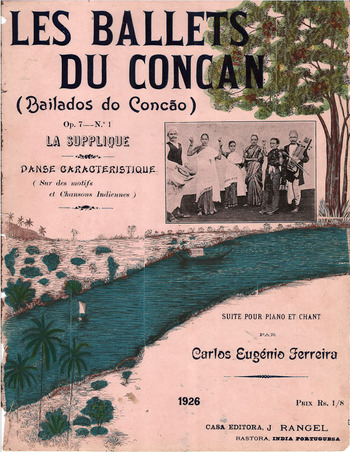

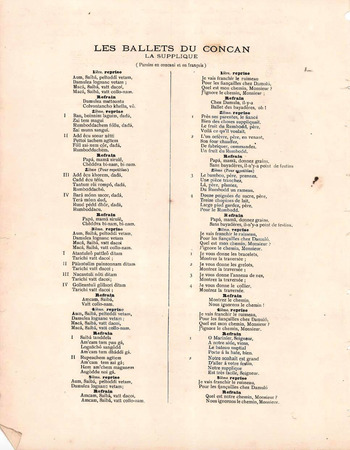

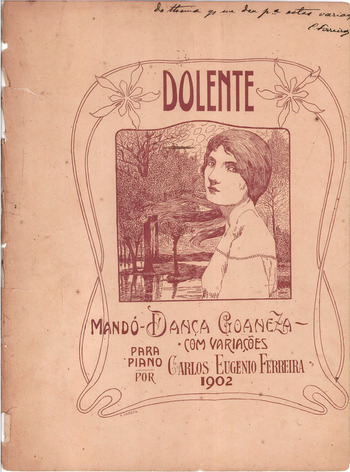

Their scores and librettos were published from Paris and Goa with ornate, art-deco-style covers. One of them, Ballets du Concan (1926) (Figure 2), contained a song, ‘La Supplique’ (French, ‘the Supplication’) (Figure 3), better known in Goa by its first sentence: ‘hanv saiba peltoddi vetam’ (Konkani, ‘Oh sir, please ferry me to the other bank’). In 1973, it entered Indian popular consciousness by supplying a melodic line and chorus to a song in the Bollywood film, Bobby.Footnote 4

Figure 2. Carlos Eugénio Ferreira, Ballets du Concan.

Figure 3. Carlos Eugénio Ferreira, ‘La Supplique: Paroles en concani et français’.

In that memorable song, ‘Na chahoon sona chandi’ (Hindi, ‘I want neither gold nor silver’), the film's eponymous Goan Catholic heroine dresses and dances in a mishmash of signifiers recalling Hindu fisherwomen and dancing girls (bailadeiras in Portuguese; kolvont in Konkani). The film's lasting influence means that even Lisbon's Casa de Goa teaches diasporic Goans to dance to ‘Hanv saiba’ in Bollywood-inspired choreography and costume.Footnote 5 This trajectory of a song considered a typical ‘dekhni’ (a genre from the ‘Dakhan’/‘Deccan’/‘South’ and associated with the Hindu kolvont) joins developments around the mando's performance to reveal how postcolonial cultural negotiations fragment and reassemble the worldview encapsulated in Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana. In contemporary Goa, the mando is still sung socially, in homes and at parties. But its dancing has moved out of the mansions of the Catholic elite to the state-sponsored Mando Festival, which has taken place annually since 1965 in prestigious venues of Nehruvian vintage. The festival showcases musical teams whose ensembles of violins, guitars, and the Goan percussion instrument, the gumott, accompany singing in European tonal harmony; some teams also compete in the dance section. Male participants dress in tuxedoes and tails; their female counterparts in sarongs, blouses, and stoles. Complemented by fans and flourished handkerchiefs, these outfits compound the difficulty in fitting the mando into preconceived notions of a ‘Indian dance’, be it ‘folk’ or ‘classical’.Footnote 6 Yet these very features are consonant with the kinaesthetic and performative principles whereby European contradances and quadrilles were creolized in extra-European spaces.

This article presents the mando as a peninsular Indic quadrille—a creolized music-dance form that attests to a web of people, cultures, and commodities connecting the Atlantic and Indian Oceans through the long timeline of the Portuguese empire and its relationships with other global and regional powers. By analysing the mando through an interdisciplinary, inter-imperial, interoceanic approach, I respond to the ‘plea’ that concludes Sanjay Subrahmanyam's seminal argument for connected histories: ‘that we not only compare from within our boxes, but spend some time and effort to transcend them, not by comparison alone, but by seeking out the at times fragile threads that connected the globe, even as the globe came to be defined as such.’Footnote 7 The mando generates a history that connects Goa Portuguesa with other parts of the world touched by Portuguese expansionism. Subrahmanyam's ‘fragile threads’ are here spun out by creolization as an embodied sociocultural process that stands in complex relation to the graphic record. Accordingly, my analysis draws on nineteenth-century descriptions of the dance, early twentieth-century lyrics, their instrumental accompaniment and notation, the dance steps then and now, outfits worn by mando dancers today, and the contexts for postcolonial performances of mando and descriptions thereof. Infusing the ‘archive’ with the sounds, beats, and moves of the ‘repertoire’,Footnote 8 I shed light on a creolizing process that, by involving the Indian Ocean world, challenges ‘the epistemological hegemony of the Atlantic model’.Footnote 9 In turn, through the mando, I bring creolization as a theory of cultural change to the study of a part of the world to which it not often applied: peninsular India.

I contextualize the mando within longue durée multiscalar interactions across the Portuguese empire as well as within the local world of the Deccan peninsula. These interactions, I argue, triggered certain creolizing processes that resulted in the mando's emergence by the nineteenth century, even as its development during the twentieth century and beyond has been triggered by postcolonial decreolizing impulses.Footnote 10 I track these creolizing and decreolizing vectors on three analytical levels: the mando sung, the mando danced, and the mando remembered. Accordingly, I first demonstrate that the mando sung to instrumental accompaniment reveals the dialectical relationship between Konkani and Portuguese lyric worlds, and between European and Indic musicological principles. Next, I analyse how the mando danced re-enacts certain ‘foundational scenarios’, or repeated performances of the compromises, betrayals, collaboration, and accommodation accompanying colonial encounter.Footnote 11 Finally, I examine how the mando remembered—in song, dance, and description—activates memories of creolization's violent intimacies and the ritualistic erasure of colonial society's inherent complicities. I explain the interdependence of these semiotic levels by showing how the mando benefits from the ludic, mimetic, and structural features of the wider genre: the creolized quadrille.Footnote 12 In the mando's case, these features point to its mythopoetic relationship to dekhnis (such as ‘Hanv saiba’) and the fast-paced dulpods that close mando performances. Drawing on the creolized quadrille suite as a semiotic system, I argue for the mando, dekhni, and dulpod as collectively dramatizing creolization in Portuguese India through a set of scenarios, personages, and emotions that, inspired by Ferreira, I call Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana. I conclude that these embodied, performed histories allow the mando to function as a negotiating tool for postcolonial Goans trying to reconcile their incorporation within India's federal structure since 1961 with the affective pull of a post-imperial, Portuguese-speaking world.

Some methodological clarifications: I am a literary historian working on creolized dance forms as embodied memory practices. From the traumas and violence of slavery and colonialism arose the cultural matrix of the Black Atlantic,Footnote 13 which included dance and music genres that now enjoy global popularity. My interest in investigating their histories alongside histories of creolized social dances of the Western Indian Ocean led me to the mando, whose memorialization occurs within the kinetic and sonic remnants of the transoceanic Portuguese empire, and the frameworks of subject formation that shape Goans through their interpellation within postcolonial India since 1961. While my philological training attracted me to the textural density of mando lyrics, an interest in embodied methodologies necessitated fieldwork conducted at staged and social settings for mando performances in contemporary Goa, especially its Mando Festival.Footnote 14 I articulate Goa's position ‘between empires’,Footnote 15 oceans, and temporalities, through an embodied philological approach that dredges up non-narrative histories of cultural contact in pursuit of the ephemerality of performance and the elusiveness of affect. Furthermore, I acknowledge the mando's memorializing, creolizing topography by including, within the heading for each of the article's nine sections, a phrase from a mando lyric that incarnates lexically and affectively its multilingual world.

Zaitu tempu zalo (‘a long time has passed’): India, Goa, and Portuguese creolization

Between the 1950s and 1970s, the mando was extensively showcased by Goan cultural brokers for local and wider Indian audiences.Footnote 16 Their writings present the mando as a quintessentially Goan product shaped by Goa's long exposure to European cultural influences as well as the tenacity of non-European, local elements, especially the Konkani language: a process succinctly captured by the quote within my section epigraph.Footnote 17 This nativist approach illuminates a particular phase in Goa's reconfiguration of identity within postcolonial India and I will analyse it as such later. But it does not shed much light on the mando's antecedents and innovations, or its similarities with (and divergences from) other dance-music genres across the Portuguese-speaking world. I attribute these gaps to the fact that ‘creole’ and ‘creolization’ are terms hardly ever applied to any aspect of India's history or culture. It is beyond the scope of this article to elaborate a case for ‘creole Indias’, although we will return to and reassess this concept in the conclusion.Footnote 18 Here, I provide a prolegomenon to this task by placing Goa within the space-time of Portuguese creolization, to explicate the mando as a creolized cultural product arising from this history. As an Indic contribution to the phenomenon of creolization, the mando reconfigures creolization as a historical process connecting the Indian and Atlantic Ocean worlds through transoceanic encounters between people of European, African, and Asian heritages. In turn, it imposes on considerations of ‘Indian culture’ two consequences of these encounters: Goa as a nodal point in the movement of elites across the Portuguese empireFootnote 19 and the movement of African and African-influenced cultural practices across the same space.

I situate the mando within cultural, economic, and juridical flows that incorporated Goan lifeways within a transoceanic, inter-imperial network from the beginning of the sixteenth century onwards. The ‘geographical histories’ of encounter are crucial hereFootnote 20: Goa's position on Western India's Konkan coast, facing East Africa across the Arabian Sea, inscribed it early within the Western Indian Ocean space that, thanks to the Portuguese empire's networks on either side of the African continent, was becoming articulated to the Iberian-led catalysis of a transatlantic economy. Vasco da Gama arrived in Calicut on India's Malabar Coast (south of Goa) in 1498. In 1510, the first Portuguese governor of India, Alfonso do Albuquerque, captured Goa from the regnant Muslim Bijapur dynasty and the neighbouring Hindu Vijayanagara kingdom, making it the part of India brought first under the Portuguese Crown's direct control.Footnote 21 Goa thus formalized the eastward expansion of the Portuguese-speaking world that, to the west, had already commenced with Portuguese settlement of Cape Verde in 1462 and Brazil in 1500. Rapidly becoming a strategic hinge between the Indian and Atlantic Ocean worlds commanded by the Portuguese empire, which, at its height, stretched from Macau to Brazil,Footnote 22 Goa, as one-time capital of its East African and Asian territories, played an important role in establishing that empire's long timeline and transoceanic reach. These aspects differentiated the Portuguese from the other European powers with which they competed for control of oceans, territories, and the master-narratives of modernity, especially the British, who would become ultimately their most territorially extensive rival in India.Footnote 23

The British only established themselves as a ruling rather than a mercantile power in India after the Battle of Plassey in 1757—two and a half centuries after the Portuguese conquest of Goa; with Indian independence in 1947, the British were also the first European power to relinquish an imperial possession under the pressure of anti-colonialism. In contrast, although Brazil achieved independence from Portugal in 1822, Portugal's African colonies did so only in the 1970s, while Goa was seized from Portuguese control by India in 1961. Right from the fifteenth century down through the twentieth, then, Portuguese cultural influence was disseminated through mercantile, religious, and juridical channels in Asia, Africa, and the Americas. This transoceanic longue durée of empire led to a distinctive history and culture of creolization.Footnote 24 If creolization indicates the creation of new demographies and cultures through the interaction (voluntary and forced) of peoples brought together in a compacted space,Footnote 25 then Cape Verde, where the Portuguese settled farmers and slaves in an inhospitable, uninhabited archipelago from the late fifteenth century onwards, became the world's first creolized society.Footnote 26 Portuguese colonialism played a key role in creating and sustaining the political, economic, and psychosocial conditions for the creolization process.Footnote 27 Consequently, a pervasive ‘racial and cultural ambiguity and hybridity’ became its characteristic.Footnote 28 Did Portuguese Goa's geographic contiguity to British India imbricate it within ‘the early demise of Creole India’ that British rule purportedly heralded?Footnote 29 Or did it participate unhindered within creolizing processes observable within other parts of the Portuguese empire?

Answers lie in the ‘dense and long temporality’ of ‘the vast, multi-secular contact zone’ of Portuguese colonialism,Footnote 30 which nourished the circulation (and recreolization) of tangible products and intangible practices resulting from creolization. These spiralling flows blurred the distinction between ‘metropole’ and ‘colonies’ and resultant binaries of racialized culture.Footnote 31 Between Portugal, Cape Verde, Brazil, Angola, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Guinea Bissau, people, plants, recipes, furniture, fabric, instruments, melodies, rhythms, and modes of singing and dancing moved to and fro.Footnote 32 The study of these circum-Atlantic material and embodied circulations has deployed and deepened current understanding of creolization.Footnote 33 Research is increasingly focusing on parallel flows within the Indian Ocean: of textiles, relics, prestige objects, theological and political ideas, debt, soundscapes, and rhythms.Footnote 34 However, we await a systematic engagement with theories or evidence of creolization derived from the Indian Ocean space.Footnote 35 Such engagement could galvanize a comprehensive transoceanic history of slavery, colonialism, and modernity by turning attention to the links and divergences between Indian Ocean and Black Atlantic networks. Here, Goa plays an important role. Its music-and-dance culture, leading up to the mando, offers exciting, but underused evidence of how cultural contact, transmission, and production across the Indian Ocean world were impacted by the contact with the Atlantic world that the Portuguese empire and concomitant inter-imperial exchanges facilitated. In the two subsequent sections, accordingly, we shall see how elite cultural forms, including sacred and secular music, became the conduits of transoceanic creolization that deposited in Goa traces of European and African expressive culture. Sedimented in the mando, these traces can be recovered by reading against the grain the proscriptions, prohibitions, and prevarications that characterize the musical scores, conciliar notices, and lexicographic attestations that constitute its archive.

Flautach’ toqui (‘playing the flute …’): the transoceanic creolization of mentalités

Benedict Anderson famously argued that ‘print-capitalism’ forged ‘imagined communities’ across supra-regional spaces in modernity.Footnote 36 In the case of the Portuguese empire, aural resources would appear to have performed this function of defining and consolidating a collective identity vastly dispersed across space and time. The Portuguese language as a source of this shared aurality is enshrined in the concept of lusofonia, now sometimes discredited for its imperial genealogy.Footnote 37 Recognizing the problematic nature of this formulation, but also the importance of sound as a connective force, ethnomusicologist Susana Sardo replaces it with ‘lusosonia’.Footnote 38 While usefully overlaying the spoken with the sung word, her neologism nevertheless retains the imperialist overtones of lusofonia's first element. Sardo's exegesis of ‘lusosonia’ as the ‘sound-trails of Portuguese culture’ also perpetuates an insidious binary between ‘Portuguese’ and ‘non-Portuguese’. In continuing to privilege aurality, furthermore, it leaves us none the wiser about the kinetic dimension that enfolds sound within dance, gesture, and performance; from another angle, it implies a potentially misleading contrast between the colonizer's language, disseminated through writing, and acoustic expression, transmitted through sound. In fact, it is a complex relationship between sound, text, word, and melody that makes possible this prima facie ‘lusosonic’ world. Its ‘sound-trails’ lead us to the creolization of mentalités along a labile interface between expressive culture's sonic, kinetic, and graphic dimensions.Footnote 39 The mando is a product of this deep structural transformation on epistemic and embodied levels.

The mando's archival entry coincides with Indo-Portuguese patronage of dance-music genres that were being enjoyed worldwide by the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Thanks to Goa's long interpellation within the Portuguese empire, dance styles that waxed and waned in popularity and fashion, and their accompanying music, were continually absorbed into Indo-Portuguese society. This article's opening epigraph describes a nineteenth-century Margao wedding at which guests danced polkas, waltzes, and varsoviennes (a variant of mazurka), all of central European provenance, as well as ‘contradances’, deriving from an earlier internationalization of European courtly dance.Footnote 40 In Goa also circulated dance-music genres specific to the Portuguese-speaking world—fados, modinhas, choros, and maxixes, or particularly popular within it, such as polkas and mazurkas.Footnote 41 This layered kinetic awareness signals more than a minuscule elite's superficial mimicry of ‘Western dances’. By at least the end of the nineteenth century, sheet music for these circum-Atlantic genres was being printed in Goa, suggesting a parity of taste and demand linking it to Brazil, Cape Verde, Angola, Mozambique, and Portugal.Footnote 42 In the early twentieth century, the afore-mentioned Carlos Eugénio Ferreira rendered Goan themes in the tempo of the waltz, maxixe, and foxtrot,Footnote 43 confirming widespread Indo-Portuguese ability to read, compose, and dance to music transmitted through European notation.Footnote 44 ‘Lusosonia’, then, is the tip of an iceberg. Through the channels of Portuguese colonialism circulated an analytical apprehension of musicality and its kinetic expression based on European aesthetic and compositional principles, which structured the relationship between melody and rhythm very differently from their Indic counterparts.

The heuristic of creolization interprets these diverse cultural principles in dynamic interaction rather than imprisoned in binaries.Footnote 45 Indeed, cultural transformation was in process from the moment ‘culture’ embarked in European-manned vessels for destinations ‘ultramar’ (‘overseas’). The arrival of Vasco da Gama on the Malabar coast with trumpeters, organists, and chanters of mass amongst his crew mobilized ab initio ‘instrumental diplomacy’ in the mutually enhancing cause of Iberian Christianity and Portuguese expansionism.Footnote 46 The impact of these novel sounds unfolded through an ad hoc, unpredictable combination of curiosity, resistance, and collaboration from the locals, pragmatism and experimentation on the part of the arrivals, and two-way mimicry.Footnote 47 These responses constitute the uneven calculus of creolization in the longue durée. Because Jesuit priests insisted that mass was most efficaciously delivered to Goan neophytes in polyphony, ‘by the 1540s the practice of polyphony was being cultivated in Goan churches’ and taught widely to Indian boys, while ‘Indian instruments were being used along with the voices and organ’.Footnote 48 The pragmatic deployment of Indic resources to realize European musicality drives the creation of novelty through creolization. But, through a deeper transculturation, ‘tonal harmony’ itself becomes a creolizing force.Footnote 49 The pedagogy of polyphony necessitated, from the medieval European period onwards, an internalization of the ability to read and explicate musical scores. Centuries later in Goa, this musical literacy determined not only how mandos were performed, but the epistemic basis of their conceptualization and composition. Today, mandos continue to be apprehended through musical scores that communicate its compositional reliance on tonal harmony and the European time signature of 6/4.

‘Playing the flute’, as my section epigraph declares,Footnote 50 Goan musicians give breath to musical scores—a melding of Indic and Latin cultures that indexes a deep creolization of mentalités. From this milieu emerged the mando, a secular Indo-Portuguese product distilled from transoceanic history. European notation as a graphic technology of transmission enabled the same sacred music reverberate across the 7,000 miles separating the Se Cathedrals of Old Goa and Bahia.Footnote 51 It rapidly disseminated, across that immense space, verse forms associated with the lyric dimension of sacred music, particularly motets and villancicos, baroque forms well attested in Goa; indeed, the mando's lyrical structure follows the motet.Footnote 52 As notation's liturgical purpose became repurposed for the composition of secular genres, musical scores became the vehicle for the latter's circulation as leisure practices wherever Europeans were establishing plantations, port towns, and comptoirs as the building blocks of empire. However, there was an inevitable gap between European notation and circum-Atlantic creolized performance.Footnote 53 In retrieving embodied practice through graphic conventions, themselves nascent and evolving at the commencement of Iberian expansionism, an important role was played by the improvisation and creative adaptability that motors creolization in both sacred and secular expressive realms. Similar tendencies impacted the transmission of European dances through instruction manuals and lyrics with mnemonic instructions that tied dances to their corresponding music.Footnote 54 The most efficient vector for the transmission of dance—the body—was also the most porous to improvisation. Disembarking dance teachers were eagerly awaited at colonial ports, only to have local kinetic codes re-inflect their movements.Footnote 55 From this dialectic between the codified, the notated, the improvised, and the embodied arises the creolized dance-music genres of the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds, including the mando—a distinct dance form, as well as the songs it was danced to.

Akam Africak aut vetam (‘to Africa I go’): Creole Atlantic in the Indian Ocean archive

Across the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, there, thus, was a simultaneity of encounter leading to cultural change. While Jesuits were teaching polyphony to Goan boys in the late sixteenth century, Dominicans in the Antilles were converting indigenes, setting up missions (and distilleries), and recording enslaved Africans performing percussive dances that had crossed the Atlantic as their embodied heritage.Footnote 56 Certain names of drums, rhythms, and ‘lascivious’ dances began circulating through the archival record: ‘calenda’, ‘chica’, ‘bamboula’, and, in the Luso-world of the Southern Atlantic, ‘lundu(m)’ and ‘batuque’.Footnote 57 Initially, they pop up under the glare of disapprobation within missionary reports. From the seventeenth century onwards, those early accounts were absorbed into the beginnings of discourse about circum-Atlantic ‘oceanic interculture’ that was bringing forth a veritable ‘Creole Atlantic’Footnote 58; they were also recycled within religious edicts and colonial travelogues in the Western Indian Ocean.Footnote 59 In 1606, the Fifth Church Council of Goa prohibited dancing to a local sung genre called the munda because such songs and their corresponding ‘lascivious and dishonest’ (lascivos e deshonestos) dances ‘incited sensuality’ (incite a sensualidade).Footnote 60 Is munda a precursor of mando? Sebastião Dalgado, the early twentieth-century lexicographer of Asian varieties of Portuguese, stated himself unsure of the etymological basis for this possibility.Footnote 61 But more telling is his ascription of an African origin to mando. Moreover, his munda and mando keep similar lexical company. The Fifth Church Council had proscribed munda alongside two other dances: sarabanda and cafrinho.Footnote 62 Three centuries later, Dalgado's Glossario Luso-Asiatico perpetuated this lexical environment through a series of cross-references that link mando, munda, cafrinho, batuque, and, via a citation of the council's triad of prohibited dances, back to the sarabanda.Footnote 63

The inter-referential circularity of these dance-music terms is the archive's testimony to transoceanic creolization operating through regional sub-circuits of cultural change within the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Sarabanda (also zarabanda, sarabande) takes us to one such sub-circuit that constituted an early Iberian imprint on the New World. The histories of dance-music genres such as villancico, sarabanda, fandango, and rumba, enfold transcultural exchanges within the Andalusian contact zone that gained traction in the Spanish Americas to return, recharged with new rhythms and movements, to the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 64 These developments are well documented, particularly in foundational ethnomusicological scholarship from Cuba.Footnote 65 A parallel sub-circuit radiates from cafrinho, which condenses the European impact on the ‘pre-colonial traffic in goods, slaves, and ideas around the Indian Ocean’.Footnote 66 Cafrinho derives from the Arabic word for ‘non-believer’, nowadays usually rendered in English as ‘Kafir’—a word that carries a charged ‘history of relations [between] East Africa and the Indian Ocean, with Swahili- and Arabic-speaking traders, and Portuguese explorers’.Footnote 67 This precolonial, Western Indian Ocean label for ‘non-Islamic Black people’ took on the Portuguese-language diminutive suffix -inho/-inha, to name a new cultural product emerging with the Portuguese advent in the Indian Ocean world. Extant in several spellings in keeping with the fluidity of creole orthographies,Footnote 68 the term circulates through the Western and Eastern Indian Ocean to mark a distinct dance-music genre as manifestation of its creolized culture. It is a felicitous instance of linguistic creolization reflecting how European expansionism restructured the ‘geography (and cosmology) of the connecting tissue of the Indian Ocean’.Footnote 69

This restructuring brings into dialogue creolization occurring on either side of the African continent. The Fifth Church Council's lexical clustering of Goan, Indian Ocean, and circum-Atlantic dances already signals slavery and colonialism's sedimented impress on this transoceanic creolized cultural matrix. To draw the Goan archive into this semantic world-system, a placeholder was needed for the concept of ‘local dance being creolised through this matrix’. In 1606, munda fulfilled this function. By 1917, mando moved into its slot. Dalgado turns to the Fifth Church Council's proscription to link munda, cafrinho, and sarabanda. But the evolving repertoire enables him bring mando into the space earlier occupied by munda. Mando is now a synonym for cafrinho, whose cognates in ‘Moluccan kafrinu’ and ‘Timorese kafrinia’ allow Dalgado to define it as an ‘Oriental’ dance originally practised by Africans (cafres).Footnote 70 He also ascribes an African etymology to mando, which is defined as a dance-music genre of the Christians of Portuguese India.Footnote 71 This perception of a shared Africanity connecting the mando and cafrinha is strengthened by Dalgado's definition of the mando's percussive instrument, the gumott, as batuque, the Portuguese-speaking world's generic term for African drums, the rhythms played on them, and their corresponding dances; the Glossario cites F. N. Xavier's 1847 synonymous use of gumata, mando, and batuque.Footnote 72 A few decades later, A. B. Bragança Pereira's magisterial Etnografia da India Portuguesa not only asserts that the ‘Portuguese introduced into its territories in India the mando’, but declares it ‘probably of African origin’.Footnote 73 Reiterating these transoceanic imaginaries, the Goan-born colonial administrator Fernando Leal even declared the mando ‘a degenerate kind of lundum’, the Afro-Portuguese precursor of creolized couple dances in the Southern Atlantic.Footnote 74

These equivalences between Goan and Creole Atlantic expressive practices are all made by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century colonial administrators. As declared by the mando lyric cited in the section heading above, from Goa to (East) Africa they went (and also came).Footnote 75 The intra-imperial movement of personnel between Mozambique and Goa consolidated precolonial mercantile comings and goings in the Western Indian Ocean.Footnote 76 The tentacular reach of Portuguese imperial bureaucracy set up a chain of relay and rumour across and beyond the eastern and western littorals of Africa, as reflected in Dalgado's yoking of mando to Afro-Atlantic batuque and an eastern African ethnic group. Dances (and the news of dances) being creolized through circum-Atlantic movement were being swirled into the Western Indian Ocean sub-circuit of cultural exchange. The lexical field occupied by munda and then mando demonstrates the Indian Ocean archive's covert memorialization of these transfusions of Africanity through ongoing creolizing processes. These archival traces of Africa lever on a transoceanic plane the circum-Atlantic world's obsession with ‘mumbo jumbo’: garbled vocalization of African percussive rhythms and chants, seen, for instance, in the chorus of ‘Ese rigor a repente’, Gaspar Fernandes's villancico from seventeenth-century Mexico: ‘sarabanda tenge que tenge/sucusumba cucumbe’ (Spanish, ‘sarabanda has what it has: sucusumba cucumbe’).Footnote 77 Through the shadows cast by repertoire across ‘the archive of slavery within and between the Atlantic and Indian Ocean networks’Footnote 78 and the transoceanic echo chamber of phantom rhythms, a common pool of ‘lascivious’ dances emerges. The memory of these dances generates an affective field around the mando within nineteenth-century accounts of elite Goan leisure practices, providing us with tools to interpret it as kinetic practice.

Taja bemfeit tuje dolle (‘even more beauteous, your eyes’): Indic moves in the creole mix

The Fifth Council's munda and Dalgado's mando bracket three centuries of an attempted stabilizing of discourse around purportedly un-Christian dances with shared African-derived traits. But what were these traits? The discursive equivalence granted by the Fifth Church Council to the Andalusian-Antillean sarabanda and the Indian Ocean cafrinho reveals an early blurring of the lines between dances of diverse European and African provenances. Given this ‘pattern and flow of cultural influences in which it is often difficult to tell whether a European or non-European cultural influence is predominant’,Footnote 79 I propose another category altogether: that of creolized dances. Through inter- and transoceanic circulation and the ‘sticky webs of copy and contact’,Footnote 80 they amalgamated, consolidated, and magnified kinetic signatures of various population groups. From West and Central African kinaesthetics came high-affect juxtaposition, body isolations, and polycentrism in response to polyrhythm,Footnote 81 and, from dances circulating within European courts came structures of dynamic interaction between men and women that generated pattern and symmetry through their movement in and out of couples.Footnote 82 By the nineteenth century, the partner hold would develop as the favoured heteronormative dance format emerging from central European urban culture. During the early phase of creolization on the plantation as a crucible for cultural change, however, features common to popular European and non-European dances, including geometric formations of circles and rows, predominated. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, therefore, a spectrum of social dances emerged that exhibited elements from diverse sources drawn into a creolizing spiral. In the case of the mando, this creole mix includes Indic kinetic elements. These elements enable us to recalibrate through a transoceanic gauge cultural processes usually examined as pertinent to either the circum-Atlantic context or a Luso-Asian, Indian Ocean one, but rarely to both.

I extract the mando's kinetic structure from performances I attended during the 2016 Mando Festival in Goa.Footnote 83 These demonstrated the mando as following an open-hold format, in which couples advance, retreat, and circle each other, interchanging positions to create figures within an outer frame maintained by two rows on either side of the stage, comprising men and women, respectively. Reinforcing the frame are rows of male and female singers, and, to one side, the (usually male) musicians. When the music and singing start, men ceremoniously invite women from the opposite row, forming couples that dance simultaneously within the space demarcated by the frame (Figure 4). Once face to face in the centre, they connect with each other through a mirroring technique (i.e. when the gentleman moves backwards, the lady moves forward, and vice versa; each circles the other in opposite directions). The mirroring is conducted on a diagonal axis with rotated torsos that, as with several Afro-Atlantic couple dances, break the body into two planes. On the lower plane, the feet move in small triplet steps, the mincing and shuffled effect exaggerated by the women's sarong-like skirt and stockinged, slipper-clad feet (Figure 5). On the upper plane, connection is generated through interlocked gazes and gender-specific accessories wielded by the hands: a handkerchief for the men and a fan for the women (Figures 6 and 7). The dancing has a slow tempo, but it concludes with a faster segment, during which the handkerchief is rhythmically flourished. At that moment, the singing switches to the quicker-paced dulpods, and the dancing becomes more animated with lateral swings discernible in the women's hip movements. The geometry of the frame is maintained until the end (Figure 8).

Figure 4. Mando dance performance at Kala Academy, Panjim, December 2016. The full video is available in the supplementary material.

Figure 5. ERC project Modern Moves Mando Performance, King's College London, May 2018. The full video is available in the supplementary material.

Figure 6. Connecting through the gaze during a mando dance performance at Kala Academy, Panjim, December 2016. The full video is available in the supplementary material.

Figure 7. Accessories being used at a mando dance performance at Kala Academy, Panjim, December 2016. The full video is available in the supplementary material.

Figure 8. Dulpod performance at Kala Academy, Panjim, December 2016. The full video is available in the supplementary material.

Danced thus, the mando's structure coheres with creolized quadrilles and contradances popular from the eighteenth century onwards wherever Europeans lived, settled, or sojourned, sharing culture with non-Europeans. By the late eighteenth century, the dance known variously as ‘contredanse’, ‘contradança’, and ‘contradanza’ had spread across Europe and its colonies, cutting across social classes as well as linguistic and imperial boundaries; its progressive elaborations resulted in the quadrille. Both kinds of dances generated meaning and pleasure through the dynamic interface between the group, its constituent couples, and the musicians who render that interface audible. As a sign of their popularity, they were profusely creolized through the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds.Footnote 84 The mando's contemporary performances suggest it is a creolized contradance of the cotillion or longways variety,Footnote 85 where men and women are arranged in facing lines; this frame is a variant on the quadrille's idealized quadrilateral, while the male–female rows also recall those of Goan Cunbi dance.Footnote 86 The mando's mandatory pairing with the dulpod, and, as I will demonstrate later, its submerged connection to the dekhni, also reflects the quadrille's development into a multi-part music-dance form. Indeed, this semiotic interdependence between the mando, dulpod, and dekhni conforms to the creolized quadrille's adaptation of the multi-part structure to express a kinetic history of creolization itself. Hence I place the mando amongst other Indian Ocean quadrilles that creolized within a space of shared linguistic, musical, and kinetic material that Mahesh Radhakrishnan calls the ‘bailasphere’.Footnote 87 Referencing the modern Sri Lankan and Mangalorean dances known as baila, derived in turn from baile (Portuguese, ‘dance’), Radhakrishnan's bailasphere includes extant variations of the cafrinho, such as the kafriinha still danced by creole Burgher communities of Sri Lanka,Footnote 88 and the Goan mando.

The dances of the bailasphere share an asymmetrical rhythm: an overlay of binary and ternary patterns with an accent on the fifth and first beats that, together with suspensions and syncopations, indicates an Indian Ocean rhythm substrate.Footnote 89 This rhythm's kinetic manifestations within the quadrille frame are deeply infused with peninsular Indic expressive culture. Heterosexual connection within the frame is managed ‘remotely’: never through interlaced arms or clasped hands through which men and women interchange places or turn around each other, but always through an interplay of gaze, glance, and gesture,Footnote 90 including wrist movements whereby the lady manipulates her fan and the gentleman his handkerchief—accessories also ubiquitous in Iberian expressive culture.Footnote 91 The social inappropriateness of physical contact in an environment shaped by Islamicate and caste-based proscriptions around touch leads not only to the mobilization of Indic performative codes to ensure connection within a call-and-response kinaesthetics shaped through the Creole Atlantic, but also to the structural anachronism of the mando itself. At a time when quadrilles and contradances were being superseded in circum-Atlantic spaces by creolized partner-hold couple dances, signalling democratizing and nucleating social trends, in Goa, a new open-hold group dance appears in the archival records, to perpetuate gestural and affective codes convergent with Indic preferences. Mando lyrics verbalize the dance's permeation by these codes—as exemplified by the emphasis on the beloved's bemfeit (Portuguese, ‘well-formed’, ‘beauteous’) eyes cited in this section's heading.Footnote 92 And, while the lovers’ longing expressed in mando lyrics recalls the Portuguese-speaking world's fondness for saudade (Portuguese, ‘longing’, ‘nostalgia’), it also resonates with the Indic rasa (‘feeling’) of viraha (‘separation’).Footnote 93

Juramentu ditam re sagradu (‘Lady! I pledge my sacred oath’): performing the status quo

It is not only negative affect that defines the lyrics of mandos. Apart from the categories of utrike (Konkani, ‘separation’) and villap (Konkani, ‘lamentation’) that Goan scholars group these lyrics into, there is a further category of mandos of ekvott (Konkani, ‘union’) that celebrates marriage as the culmination of love.Footnote 94 Marriage is also the focus of several mando lyrics categorized as fobro (Konkani, ‘news’).Footnote 95 Running through mandos in these diverse categories, moreover, is a preoccupation with what rasa theory calls shringara, or female adornment directed towards male appreciation.Footnote 96 These verbal emphases on heterosexual attractiveness leading to the expectation of conjugal union (whether realized, denied, or delayed) corroborate my reading of the mando dance as a creolized quadrille formed on peninsular Indic soil. Like creolized quadrilles in general, it performs as a ‘public secret’Footnote 97—a history of cultural mixing under coercive conditions. That history is remembered in the quadrille's patterned dynamics, which subordinate heterosexual couples to the overarching logic of the group. Dance thereby becomes a balancing act between conflicting and competing groups, between mourning the violence of encounter and celebrating resilience through the birth of newness.Footnote 98 If this danced maintenance (and memory) of creolization as the new status quo is a feature of mando performances, what encounters are remembered and sublimated thereby? Clues here lie in the semiotics of the costumes worn by contemporary mando performers: musicians and singers as well as dancers. The mobilization of Goan sartorial history within the performance of memory is enabled by the folklorization that creolized quadrilles worldwide have undergone in the postcolonial period, bestowing on performers carte blanche to ‘dress up’ in order to recall another temporality.Footnote 99

The mando's agonistic structure as balancing act between opposing groups motivates a distinction between what male and female performers respectively wear. While the men wear formal European attire, the women's outfit, already described earlier in this article, is called pano-baju (Portuguese) or torhop-baz (Konkani).Footnote 100 Comprising a tubular skirt reaching the ankles, a long-sleeved tailored blouse, and a shoulder stole, its decorative elements include vegetal motifs embroidered in gold on the blouse and borders on the skirt running longitudinally down the middle and horizontally along the lower edge. Accessories include elaborately worked gold bangles, necklaces, and earrings; tortoise-shell head combs; filigreed fans in tortoise-shell, mother-of-pearl, or bamboo; and low-heeled, soft slippers. This ensemble recalls neither ‘Western’ nor ‘Indian’ traditional dress, but takes us instead to the sarong and blouse combinations of South-East Asia, as the Goan designer Wendell Rodricks demonstrated.Footnote 101 The embroidery, metalworking, and cutting techniques, as well as the materials used, attest to cultural transfer, exchange, and adaptation in the Indian Ocean world stretching from Japan to Persia, within which the Western Indian littoral was decisively positioned.Footnote 102 The names for these elements encode layers of taste-making—thus the woman's shoe, called a chinelo in Goa, recalls China, while combining elements from the Persian zapat (from Spanish zapato, ‘shoe’) and Mughal slippers; pano is Portuguese for wrapped cloth and is a word used widely throughout Africa, while baz is a Portuguese-influenced Konkani pronunciation of the Persian baju (‘arm’), denoting the characteristic long sleeve, which nevertheless was shortened to three-quarter lengths to show off gold kanknas (Konkani, ‘bangle’, from Sanskrit kangana) ‘similar in spirit to Deccan coastal gold ornaments’.Footnote 103

While the male mando performer's outfit invites straightforward association with the Portuguese colonizer,Footnote 104 that of his female counterpart radiates multiple histories of transoceanic creolization enacted on the woman's body as a conduit of cultural change. By the beginning of the twentieth century, sarong-blouse outfits were firmly associated with women of mixed-race communities throughout the Eastern Indian Ocean.Footnote 105 Goan memory attributes the pano-baju's early twentieth-century popularity to its association with the mestiça wives that Portuguese administrators married in the Malaccas and brought to Goa.Footnote 106 Collective memory also associates the pano-baju with the heydays of the mando as a social dance practised amongst the elite denizens of Indo-Portuguese mansions, even though, in contemporary Goa, it is worn only during mando performances, including those staged for filmed documentation.Footnote 107 Thus, in Goa, this outfit is consistently recalled in conjunction with a danced memory of creolization. It materializes the structure of the dance as a courtship encounter between the colonizer and the colonized subject. This performance of creolization through a ‘primal scene’ staging ‘the scandal of cultural miscegenation’ is common across the circum-Atlantic world.Footnote 108 These ‘foundation scenarios’ assign the role of the colonizer to the man and that of the colonized to the woman, highlighting this role play through appropriate costume.Footnote 109 For instance, in the Angolan Rebita, also an open-format group dance like the mando, the men are dressed exactly like the male mando dancers, while the women wear ‘local’ dress.Footnote 110 Where the mando diverges from this and other examples of danced foundation scenarios is that its ‘local woman’ wears an outfit that asserts creolization through anterior and ongoing transoceanic encounters.

The sumptuous and lustrous materials (brocade, velvet, silk, tortoise-shell, mother-of-pearl, gold) of the pano-baju are metonymic of the elite status enjoyed by the community that the ‘local woman’ represents.Footnote 111 It consolidates the gravitas of the mando sung, which proclaims a message of cultural capital: of socio-economic gain rather than loss as a consequence of the creolization enacted by her courtship dance with the ‘foreign man’. Its motet structure, rendered by voices in intervals of third and sixth parallels,Footnote 112 derives from the centuries-long creolization of mentalités catalysed by the Church that I argued for in an earlier section of this article. Mando lyrics deepen this acoustic alignment with institutional power through Konkani studded with elevated lexis drawn from two high-status languages. From Sanskrit derives a cosmological and planetary vocabulary—surya (‘sun’), noketra (‘stars’), tsondrima (‘moon’), rendered in the prestigious Salcette accent on Konkani. From Latin, channelled through Portuguese, derives a vocabulary calquing liturgy with law—such as the lover's juramentu sagradu (from Portuguese juramento sagrado, ‘sacred oath’) in the section heading above.Footnote 113 The Portuguese phrase is seamlessly incorporated within the sentence through a conjugated Konkani verb (ditam) and the Indic vocative particle re that is integral to the cadence of the lyric's line. This deposition of a specialized Portuguese lexical field into the very syntax of Konkani is a ubiquitous feature of mando lyrics, as the section headings throughout this article demonstrate. The creolization processes that manifest in the mando on multiple levels are again in evidence—not through a linguistic creole, as might be expected,Footnote 114 but through a Konkani fundamentally transformed by the very encounter that the mando's performance of the status quo memorializes.

Polkist fulambai tuka kitea zai? (‘why pursue polka dancers, flower-girl?’): desire's circuit

The mando, like other creolized quadrilles, mobilizes the quadrille's kinetic structure to perform the collective memory of ‘tabooed desire’ and ‘the scandal of cultural miscegenation’.Footnote 115 Its musical composition and linguistic style ratify the creolization of mentalités characterizing Goa under the Portuguese. However, its sartorial allusions to the rich stuffs of transoceanic trade and the classicizing Konkani of mando lyrics contrast sharply with the creolized quadrilles of the Caribbean and Western Indian Ocean islands, typically danced in clothes reminiscent of plantation-era sumptuary codes, to lyrics sung in various Creoles. While the insular creolized quadrille reflects the aspirations of the newly emancipated, then, its peninsular Indic counterpart transmits the retention of power by the Indo-Portuguese elite—mapping onto the difference between the geographical history of islands, which stimulates creolization by encouraging cultural rupture, and the continuing, complicated relationship with hinterlands that littoral and peninsular geographies afford.Footnote 116 These aligned differences crystallize in the mando, allowing us to refine a theory of creolization as the unpredictable generation of culture under conditions of duress. Divergences and overlaps between distinct sites of creolizing processes (for example, plantation versus enclave) and socio-economic axes of cultural transfer (for example, slavery versus mercantilism) can be calibrated through the mando's ludic and kinetic resources,Footnote 117 particularly its relationship with the music-dance genre dulpod, which furnishes the concluding section of a mando performance. Characterized as ‘a song of joy’,Footnote 118 the dulpod's quickened rhythm, rendered graphically as 6/8 rather than the mando's slower 6/4, progressively distends the mando's stateliness. Its onset signals the performance's imminent descent into a world populated by an affectionately stereotyped cast, which completes the dramatis personae of Indo-Portuguese creolization.Footnote 119

The introduction to an influential anthology of dulpods provides an exhaustive list of these characters, including the advogad (‘lawyer’), alfiad (‘tailor’), beatinny (‘devout spinster’), bikari (‘beggar’), firngi (‘white man, Portuguese’), forvoti (‘sawyer’), harvi (‘fisherman’), iscrivaum (‘scrivener’), inglez (‘Englishman’), kolvont (‘temple dancer’), marinheir (‘seaman’), maskany (‘fisherwoman’), mistis (‘mixed-race person’), padri (‘priest’), and render (‘toddy-tapper’), but somewhat mysteriously absent from the editors’ lively litany are the two figures of my section heading above: polkist and fulambai, whose interaction forms the topic of at least one still popular dulpod, ‘Ago fulambai’ (Figure 9).Footnote 120 Addressing a young woman as fulambai (‘flower-girl’), it recounts her obsession with the motty-motte polkist (the ‘expert polka dancer’). The blame is laid at Fulambai's door: ‘Why are you after the expert polka dancers?’ asks the first verse; ‘expert polka dancers are in your heart and soul (kalliz any'm curassaum),’ concludes the penultimate one. Yet it is clearly a mutual attraction: ‘expert polka dancers are winking at you,’ warns the second verse; ‘expert polka dancers are always around you,’ iterate the third and fourth. The chorus and the concluding verse thread these declarations of mutual attraction with the tropical flowers abolim (‘orossandra’) and mogra (‘jasmine’) that Fulambai accessorizes herself with and carries baskets of.Footnote 121 While these flowers, invoked through their Konkani names, bestow on Fulambai an intensely local aspect,Footnote 122 her dialogic relationship with the polkist establishes her as an aspirational figure within the dulpod's world. Whether expert or student, a polka dancer is a catch.Footnote 123 To attract him, Fulambai needs to be able to match his steps: ‘without the polka,’ one dulpod asserts, ‘you cannot get stylish husbands.’Footnote 124

Figure 9. Dulpod dance performance at Kala Academy, Panjim, December 2016. The full video is available in the supplementary material.

At the same time, Fulambai and her ilk infuse some necessary ‘salt and feni’ into the proceedings.Footnote 125 Whenever they enter the scene in dulpod lyrics, hips move and energetic contradanças and the rambunctious variety of quadrille called the Lanciers are mentioned.Footnote 126 The lyrics thus celebrate not only Fulambai's exposure to European social dances brought into the quotidian space by the polkist, but also her transformation of those dances into something altogether more zam zam (‘vibrant’).Footnote 127 The local flower(-girl)'s transformative agency is enhanced by metonymic contiguity to Konkani, which, in absorbing the European dance terms syntactically, extrudes the creolizing process onto its surface: the word ‘polka’ always appears in dulpods already absorbed into Konkani syntax—either through the construction polkist or in conjunction with ‘waltz’ within the formulaic phrase valsam-polkam.Footnote 128 These European social dances function as signifiers of a particular world within dulpod lyrics, whose contours emerge through oppositional status with Fulambai and her tropical flowers. This opposition is strengthened through the lexical differences between the lyrics of dulpods and mandos. While the mando expresses courtship, love, and fidelity through its elevated lexis, the dulpod evokes daily life, often in a sexually suggestive tone. However, dulpod lyrics conjure up these opposed worlds precisely to suggest their capacity to seep into each other. Weddings, saints’ days, market days, and carnivalsFootnote 129: this festive temporality punctuates the lyrics of several dulpods, offering its dramatis personae sites of encounter, through and in dance. Because the dulpods present lyric fragments, not concluded narratives, these encounters remain of the moment; nowhere do we hear of Fulambai and the polkist settling into a ‘happily ever after’.

These lyrics that memorialize dance as enabling encounter are matched by a dance in which desire becomes a non-teleological circuit: those playing the roles of Fulambai and the polkist advance and retreat towards each other; they circle each other. We note the same libidinal economy of couples interacting within a group that characterizes the mando. Within contemporary performances, dancers segue from mando to dulpod without changing their outfits; the singing style remains the same, as does the rhythm, although the tempo quickens and, as noted earlier, hips indeed move—though only as much as the narrow pano-baju permits. The dulpod thus displaces the mando's courtship between the European man and the elite local woman to a relatively Rabelaisian version, devolved onto the elite local man and non-elite local woman. The opposed social worlds of mando and dulpod lyrics reiterate these different moods of their corresponding dances. Yet, because always contiguous, these dances repeat kinaesthetically the performance of ‘opposites attract’. This pattern of self-similarity and repetition with difference follows the fractal logic that dictates the creolized quadrille's multi-part structure or ‘suite’.Footnote 130 In quadrille traditions and several couple dances that developed from them, suites function as repertoires that memorialize a spectrum of kinetic possibilities resulting from the creolization process. Hence the Tango ‘tanda’, the Antillean quadrille ‘haute taille’, or the Seychellois ‘kamtole’ all enfold within a set sequence, dances of different tempos, postures, affects, and lyrical emphases.Footnote 131 I suggest we consider the mando and the dulpod as comprising an attenuated mando suite in two parts. As constituent parts, the mando and the dulpod present respectively the local and transoceanic dimensions of the foundational scenario of creolization, while the suite as a whole performs these dimensions as complementary and interlocked.

Kolvontancho khellu (‘the dancing girls play’): transoceanic dance, riverine crossings

The mando suite's cultural intelligibility depends on what it includes as much as what is deemed to be outside it. It activates a particular memory of cultural encounter through its constituent parts, the mando and the dulpod, that together signify the dialectical relationship between creolization on transoceanic and local planes. But, in keeping with its underlying fractal logic of reduplicating self-similarity, the entire suite also exists in a parallel dialectic relationship with the dance-music genre dekhni. Structurally separated from the mando suite within contemporary performances but tied to it nevertheless through semiotic interdependence, the dekhni sheds light on how creolization is memorialized as having shaped not just the Indo-Portuguese elite—but also those elements within local society that, from the perspective of that elite, escaped creolization. The creolizing matrix here is understood as Christianity: conversion is the watershed that separated the new from the pre-existent. The figure within which this intimate otherness crystallized is the dancing girl of Hindu temples: the kolvont/bailadeira. Like Fulambai of the dulpods, she is associated with flowers: through her floral accessories and through the names she bears, which reference both the general ‘flower’ as well as specific local varieties. Dekhnis also name what she loves to eat: sweet and sour fruits, spicy vegetable preparations, and the addictive betel nut.Footnote 132 She dances not to court a would-be husband, but for enjoyment—her own and her audience's—and to placate her capricious gods.Footnote 133 Through her earthy sensuality, the dekhni evokes the Hindu-temple culture that had been banished, symbolically and materially, to ‘the other side of the river’ in the course of the conversion of Goan elites to Catholicism.Footnote 134

The metonymy of the kolvont's desirability and the riverine cast of this symbolic topography is best captured by the dekhni ‘Hanv saiba’, contributing to its popularity long before and after its showcasing in the film Bobby. Its lyrics depict the kolvont and her friend pleading with a ferryman to take them to the river's farther bank, where the wedding of one ‘Damulo’ is taking place. In exchange for the crossing, they offer the ferryman their anklets, bracelets, necklaces, and nose rings; each verse focuses on the act of pointing to and taking off these items of jewellery from the corresponding parts of the body, bestowing the lyrics with excellent kinetic and mimetic potential. The ferryman's reiterated refusal is punctuated by a refrain that shifts the scene to Damulo's wedding canopy under which ‘kolvonts play’ (kolvontancho khellu).Footnote 135 The dekhni's interest, thus, is not so much in the success (or otherwise) of the kolvont's crossing, but in her ability to bargain for mobility through the accrued capital that she wears festooned on her body.Footnote 136 At the same time, the repeated reference to dancing girls enjoying themselves at Damulo's wedding emphasizes the kolvont's circulation outside the juridical and aspirational coupledom enacted in the mandos and dulpods.Footnote 137 Nevertheless, while her distance from the world of courtship and matrimony is emphasized by the fact that it is another's wedding she has to attend, her economic dependency on the institution of marriage is signalled by her willingness to invest her own capital to facilitate her ferry ride. The river, which both separates and connects, deepens the ambiguity of the kolvont's social position, but heightens her allure.

The riverine boundary can be read as the River Zuari, which, through the Portuguese New Conquests, demarcated Hindu from Catholic territories in Goa. But the kolvont's allure derives from an earlier ‘flight of the deities’ that was initiated during the Old Conquests.Footnote 138 Indeed, she enters the archive coterminous with the earliest appearances of ‘lascivious dances’ being creolized and censured in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean worlds. The same Fifth Church Council of 1606 that prohibited the munda, sarabanda, and cafrinho, as we saw earlier, also banned groups of moças bailadeiras (‘young dancing girls’).Footnote 139 Despite the Goan Inquisition that the Church Councils heralded, the bailadeira's role within Hindu rites continued, albeit within villages on the periphery of the Old Conquests to which the Hindu gods had fled.Footnote 140 By the time of the New Conquests, her symbolic freight increased through conflation with British obsession with nautch-girls and Indian nationalist discomfort with devadasis.Footnote 141 Meanwhile, by the early twentieth century, troops of such ‘dancing girls’ were crossing back and forth between these ‘discrepant empires’ centred in Goa and Bombay.Footnote 142 Their reinscription into the mythopoetic realm via the dekhni, a genre that Goans acknowledge as a product of elite Christian imaginings of the Hindu other, codifies in performance and lyric that other's symbolic persistence. The kolvont enables the dekhni to sublimate the alienation from a part of the autochthonous self that conversion psychically signifies. Dekhnis such as ‘Hanv saiba’, composed by Indo-Portuguese elites dwelling in the very districts that had become seats of Brahmin Christian culture following the Old Conquests, represent a ritual ‘activation of memory’ that propitiates perceptions of complicity with colonial violence, here crystallized in the Goan Inquisition.Footnote 143

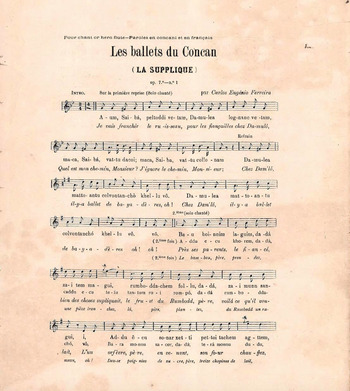

Undoubtedly, versions of ‘dekhni’ as ‘local song of the Deccan’ existed ever since there were proximate ‘non-local’ cultures. But, by the end of the nineteenth century, Indo-Portuguese composers activated collective memory by folklorizing the dekhni,Footnote 144 refashioning lyrical fragments and melodies into compositions set to music arranged in European scores—as Carlos Eugénio Ferreira did with ‘Hanv saiba’ (Figure 10). He composed this piece for his Ballets du Concan, indeed primarily as entertainment for his social group. This group included Indo-Portuguese ladies who posed for photographs dressed up as their Hindu counterparts, draping the nine-yard sari between their legs in the Deccan manner, adorning themselves with gold ornaments that, like the altarpieces of their churches, marshalled Deccan craftsmanship into the service of Indo-Portuguese affective exigencies.Footnote 145 The dekhni performs creolization as mimicry that generates their collective Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana as a self-reflecting hall of mirrors. As song, dance, and dancing girl of the Deccan, the dekhni is an object of desire: for the composer, for those who danced it mimicking the dancing girls, for those who danced with them, and for the mando suite itself. Its auto-orientalizing oneiric realm projects onto the space of social dance: elite Christian imaginings of an intimately other(ed) local Hindu culture. The language and scenarios of dekhni lyrics verbalize this ludic seepage between genres as a mise-en-abyme of creolization that the mando suite manifests. Transoceanic and riverine circuits of desire intersect as the kolvont, wearing saris of seda (Portuguese, ‘silk’), entices the desai (Konkani, ‘village headman’) to ‘wiggle his hips’ even as she ‘bends’ hers to the sounds of the ‘cornet’ (corneticha sadary kolvont/ox'm ox'm morhote).Footnote 146

Figure 10. Carlos Eugénio Ferreira, ‘La Supplique’, opening page of musical score.

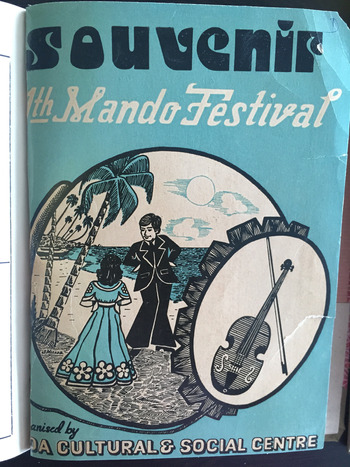

Mannyka atam fel'cidade polleuchem (‘I must now seek felicity’): a strategic forgetting

Just as Portuguese words and a creolized habitus seeped into mando, dulpod, and dekhni lyrics, the boundaries between their corresponding dances and their affect-worlds were also permeable historically. In 1886, António Lopes Mendes depicted a sari-wearing kolvont and seated musicians and singers, captioned dança do mandó em casa das bailadeiras (Portuguese, ‘Mando dance in the house of dancing girls’) and described as mandó rudimentar, à antiga (‘a rudimentary mando of ancient times’).Footnote 147 Conversely, dekhnis were ‘sung in sessions of Mando, after the Mando and among the Dulpods’Footnote 148 and kinetically interpreted through the mando suite's creolizing structure. In 1926, Carlos Eugénio Ferreira presented ‘Hanv saiba’ with an accompanying théorie de la danse par quatre couples, cavaliers et dames (‘dance instructions for four couples comprising men and women’), in French (Figure 11).Footnote 149 This terminology and the choreography he provides are those of the quadrille; moreover, in line with creolization's constant innovations, he instructs the couples to incorporate the recently fashionable one-step into their footwork. Ferreira was not unique in thus interpreting the dekhni: it had been presented as a contradança de honra (Portuguese, ‘contradance of honour’) at an elite wedding in the 1900s, under the direction of Lourenço Henrique Dias, leader of the Banda Nacional de Salcete.Footnote 150 Around the same time, the young Goan writer Floriano Barreto described mando dances descending into a wild denouement ‘reminiscent of popular Hindu Goan music’, starting in an ‘elegant and delicate’ manner, but moving to an ‘unbelievable prestissimo … equal[ling] that of a gallop’ during which ‘all sing in a great chorus replying to the body of singers proper … and the gumott is played upon with impetuousness’; the result is a ‘fear-arousing din, a vigorous orgy of drumming, which is soon mixed with sharp cries and piercing whistles’.Footnote 151

Figure 11. Carlos Eugénio Ferreira, ‘La Supplique: danse characteristique, théorie de la danse’.

Contemporary mando performances seem quite distant from these boundary-breaching exertions. The dance today has a slow tempo and is decorous, as couples execute their dainty steps through postures of restraint. Even considering that these are staged performances that last for a pre-determined and short duration, this mando hardly accords with Barreto's frenetic dancers who, by the close of the evening, are mopping brows, sweating and panting, and reaching out for water. Hence, Susana Sardo considers Barreto's account of the mando evocative of the way in which the dulpod, rather than the mando, is danced.Footnote 152 Her observation appears based on the accelerated section danced to dulpod lyrics that closes mando performances today, and on an assumed strict separation of these genres. However, Barreto's description is concordant with the concept of the mando suite that I have advanced, wherein mando names both the suite and one of its constituent dances. This polysemy, common in transoceanic creolized dances, derives from the fractal logic of creolization that generates segments within dance suites distinct in tempo and mood, yet prone to seeping into each other.Footnote 153 Barreto's contemporary, the satirist Jip (Francisco João da Costa), described dancers moving from o mando bom (‘the good mando’), sung with voz dolente (‘mournful voice’) towards a dança louca (‘the crazy dance’); the mando dolente reappears in Carlos Eugénio Ferreira's oeuvre (Figure 12).Footnote 154 These accounts illuminate how mando was danced at the turn of the century as an improvised social act. Its opposing dimensions, which, following da Costa, we may term dolente and louco, are reflected in Barreto's concluding summary of the mando as a diptych into whose panels condense this opposition.Footnote 155

Figure 12. Carlos Eugénio Ferreira, Dolente: Mandó, dança goaneza, cover

The blurring of mando, dulpod, and dekhni through performance contrasts with their presentation as separate(d) genres within discourse. The archive registers successive attempts to sanitize and domesticate the creolized mando suite through such separation, conscripting the dulpod as mediator between the mando and the dekhni, and consigning the dekhni to the status of the noble mando's itinerant other: ‘Like the monkeys on the trees on the other side of the river, the dekhni can never stay for long in one place.’Footnote 156 This comment, made in 1967 by dekhni editors whose surnames align them with the same elite constituency that ‘created’ the dekhnis at the turn of the century, perpetuates the auto-orientalizing worldview of Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana. Ferreira's capture in writing and notation of ‘Hanv saiba’, and its presentation as the opening dekhni of the 1967 edition on dekhnis, correspond to two political contexts for discursive interventions into the mando's performance: ‘the birth of the republic in Portugal in 1910, followed by a momentous and tumultuous decade when Goans hoped to govern themselves’Footnote 157 and the dramatic incorporation of Goa into postcolonial India in 1961, which loomed as a possibility ever since India's independence from Britain in 1947. Both moments triggered intense renegotiations of identity, status, and affiliation for the Indo-Portuguese elites whose creative and social world the mando represents.Footnote 158 The archive is sedimented by such interventions to mobilize repertoire into politically expedient versions of the self, even as repertoire performs and commemorates earlier processes of self-making in the face of expediency.

These processes enact a strategic forgetting of creolization's routes in search of ‘felicity’—as signalled in the section epigraph.Footnote 159 The ‘birth’ of the dekhni around the 1900s signals readjustment of the semiotic system that I am conceptualizing as the mando suite. Mythopoetic resources that had congealed in foundation scenarios during the Old Conquests period were recycled through mimicry and play to bring forth a newly porous partition between Catholic ‘self’ and Hindu ‘other’. Barreto's account of mando, dating from that period, was translated from Portuguese into English in 1954, for a special issue of the Indian art journal Marg dedicated to Goan art and culture.Footnote 160 The system was shifting again in response to political currents: that year, visas became necessary to cross into Goa from elsewhere in India.Footnote 161 Tellingly, the Goan intellectuals contributing to this issue make Barreto's account available to a wider, English-speaking public while distancing themselves from its Dionysian emphases. Interventionist footnotes and translator's erasures vigorously repudiate the recognition, by Barreto and others of his generation, of a creolized Atlantic genealogy within the mando.Footnote 162 Instead, Goa's creolized culture is reinterpreted through Nehruvian discourses of syncretism, with an emphasis on its statelier elements that could resonate with an autochthonous antiquity seemingly inherited by other regions of India. Such reinterpretation, already foreshadowed in the 1954 Marg issue, progressively repackaged the mando suite as an art dance after India's takeover of Goa in 1961.

‘The Indians have arrived’: transoceanic creolization in the postcolonial present

In 1961, India itself had been independent for only 14 years. It was reorganizing its administrative and cultural structures through an amalgam of the residues of anticolonial resistance to the British empire and the retention of colonial institutions. In this milieu, outliers such as Goa's Indo-Portuguese elites had little room to manoeuvre for the norms and mores that they had inherited from the Estado da India. Goa's transformation from a prized imperial possession of Portugal to a small unit within the federated Indian Republic meant their reinscription within an Anglophone, Hindu-majority public sphere. How was this identity to sit alongside their now ruptured participation within lusofonia? As Maria Aurora Couto recalls in her memoir of life in Goa before and after its incorporation into India: ‘The Indians have arrived, said the Goans. The feeling of confusion and insecurity, intense among Christians, was felt by every Goan, though not everyone will admit to it today.’Footnote 163 Compromises were often the easiest way out to secure ‘felicity’. For instance, Couto's husband was invited by the Indian government to be part of the new civil service for Goa, which, together with the smaller Indo-Portuguese entities of Daman and Diu, constituted a Union Territory for the immediate future. Couto's memoir illuminates the psychosocial instabilities of interpellation within a postcolonial framework that had not devolved from the ‘empire of one's own’; it recalls the Goan elite's prime concern in 1961 being ‘the possibility of survival without radical change’.Footnote 164 The repackaging of the mando as a venerable Indo-Portuguese dance-music genre, on a par with architectural and material legacies of Goa's Christian art, was part of this process of survival.

Already in the 1954 Marg issue, ‘survival’ meant dovetailing Goan cultural processes and products, tangible and intangible, into pan-Indian trajectories of postcolonial self-fashioning.Footnote 165 However, where Bharat Natyam, Kathak, Odissi, and Manipuri dance were being mapped as regional contributions to the reinvention of classical Indian culture, the mando, with its dancing couples, tonal harmony, violins, gumott, sarongs, and suits, sat oddly within the hardening dichotomy between ‘classical’ and ‘folk’ dance through which Indian dances were being classified by postcolonial cultural institutions.Footnote 166 Hence, in the 1954 Marg issue and subsequent discussions during the following decades, mando becomes re-presented as Goa's ballo nobile (Italian, ‘noble ballroom dance’).Footnote 167 This high-status label contrasts with the packaging of creolized quadrille traditions worldwide as ‘folkloric’ and therefore demotic,Footnote 168 but it correlates with the ostensibly puzzling yet, from a South Asian perspective, perfectly explicable category of ‘Brahmin Christian’.Footnote 169 Its relationship to Portuguese imperial culture and the high culture of the Catholic Church fuels mando's postcolonial re-brahminization, which has proceeded through its showcasing as elite, traditional, folkloric, classic, European, and indigenous all at the same time—most evidently through the evolving resources of the annual Mando Festival. However, the price that the genre has paid has been the marginalization of its danced aspect. The mando is de-kineticized: improvisation disappears, the social and spontaneous dimension recedes, and it becomes fossilized as dance; the body's susceptibility to imagined impurity is eliminated as a source of subalternityFootnote 170 and the dance itself purified further into the regulated structure of mando followed by dulpod. The kolvont is cast rigidly outside the mando's ambit—a development aided by her ‘Bollywoodization’ through Bobby.

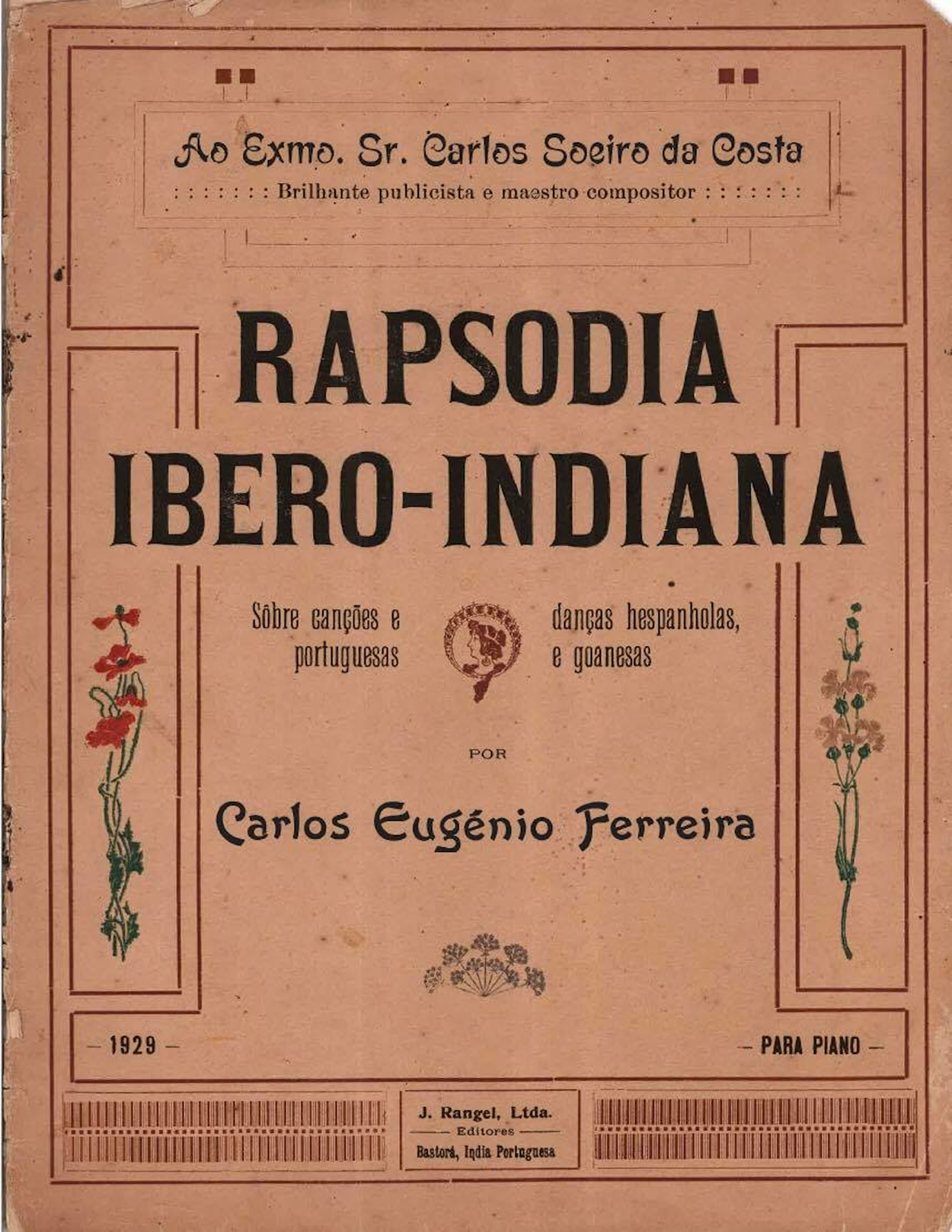

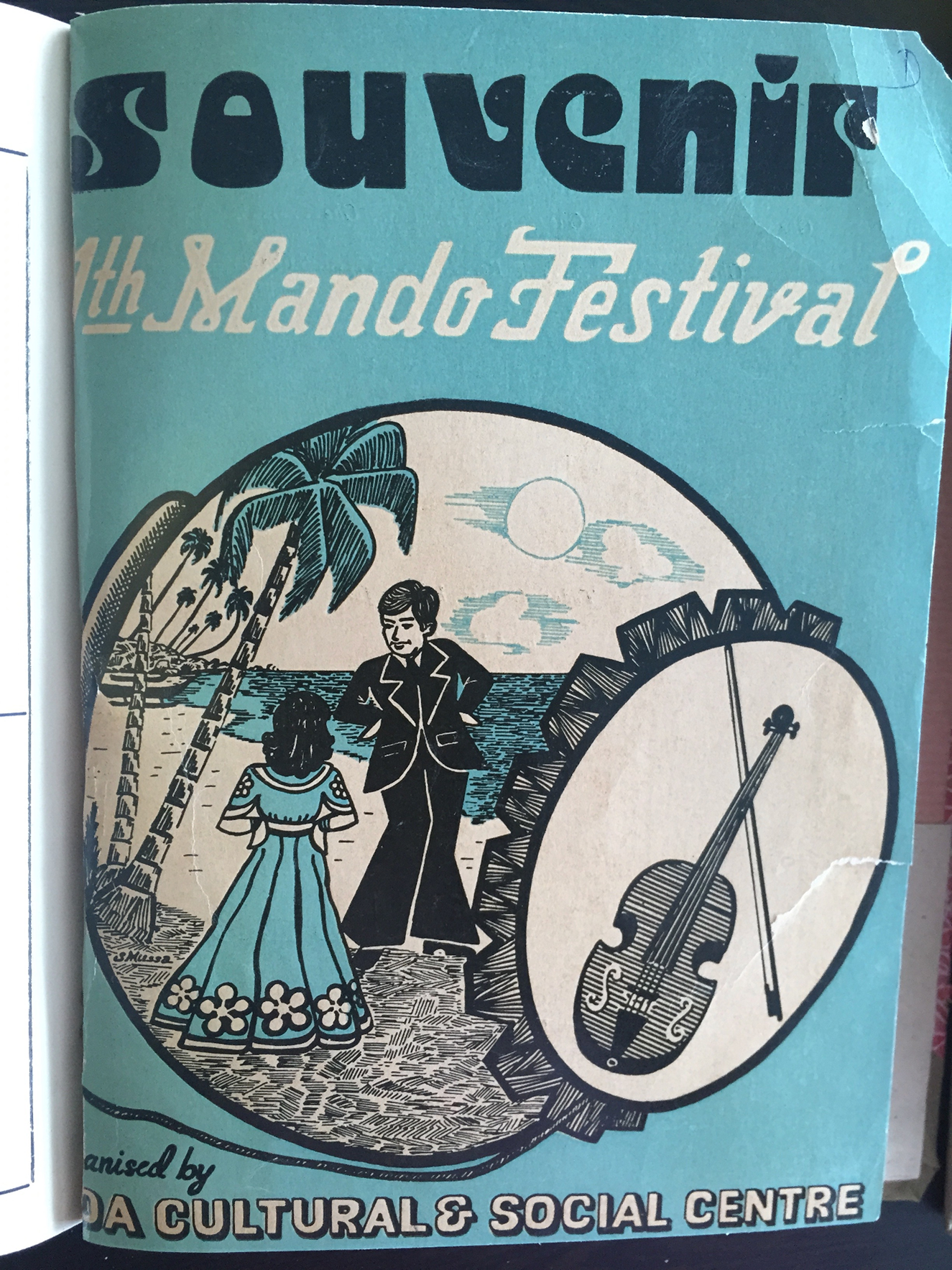

Yet the mando's history of transoceanic creolization also bestows on it two useful bargaining chips within the clamorous marketplace for resources that is postcolonial India: the Konkani language of its lyrics and the beat of the ‘aboriginal drum of Goa’, the gumott.Footnote 171 ‘Throughout the known history of his land,’ declares Lucio Rodrigues in his contribution to the 1954 Marg issue, ‘the Goan has not cared who made the laws of Goa, so long as he could make songs in the language of his people, Konkani. All that he asked for was a gumott, a violin, and company of good cheer.’Footnote 172 While even a synoptic account of the complex language politics around Konkani in Western India is beyond this article's scope,Footnote 173 I want to emphasize the role played by the mando's Konkani lyrics in enabling its Catholic speakers to accrue cultural capital through declaring their ‘passions of the tongue’ at a time when a federal ethnolinguistic politics is taking shape in postcolonial India.Footnote 174 Conjoining the mando's utility as a vehicle for Konkani poetry of the highest calibre is its musical dependence on the gumott—a membranophone percussion instrument made out of clay and the hide of a local monitor lizard.Footnote 175 Used within Hindu-temple drumming and Catholic entertainment alike, a synecdoche for both indigenous fauna and local soil, the gumott bears considerable material and symbolic freight in the postcolonial reception of mando, as borne out by the regular graphic representations of this instrument on the covers of Mando Festival souvenirs (Figure 13).Footnote 176 Moreover, its playing remains outside the notated score (despite the score presenting its overall rhythmic composition as 6/4 and, therefore, through European convention).Footnote 177 On stage in particular, the improvisational technique used by the gumott player contrasts vividly with those of the violinists and guitarists, who follow the sheet music on stands in front of them.Footnote 178

Figure 13. A gumott on the cover of the eleventh Mando Festival Souvenir