Introduction

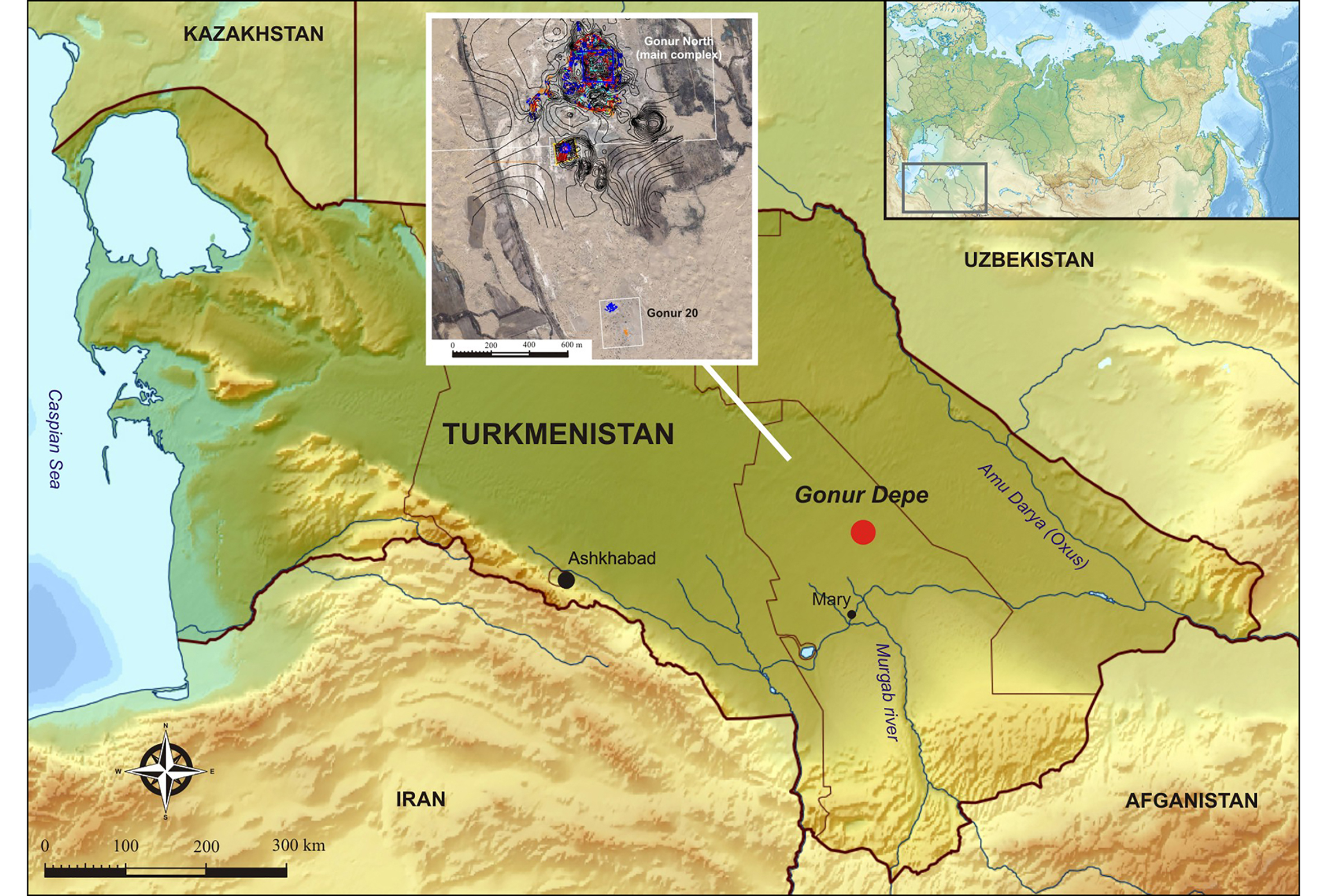

Situated in south-eastern Turkmenistan, in the Karakum Desert on the ancient delta of the Murghab River, Gonur Depe (2300–1500 ВС) is one of the largest and best investigated sites of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (or Oxus Civilisation) (Figure 1). It was discovered in 1972 by Viktor Sarianidi, who directed excavations there until his death.

Figure 1. Location of Gonur Depe and Gonur 20 (© Margiana Archaeological Expedition).

Today, the Margiana archaeological expedition continues its investigation as part of the agreement between the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Ministry of Culture of Turkmenistan. In 2018, an interdisciplinary project began with the aim of reconstructing ancient Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex technologies in the context of cultural interaction among the Bronze Age populations of Eurasia and the natural environmental dynamics of Central Asia. The project involves targeted excavations on the site, namely at the palace, at the north-east periphery of North Gonur as well as at several neighbouring settlements located some distance from the main complex. As part of this study, excavation was undertaken during the spring of 2019 on the satellite settlement Gonur 20; it was here that the first example of Margiana polychrome painting was found. This painting is reported here.

Gonur 20, grave 78 and its archaeological context

Gonur 20 is situated around 2km south of the palace-temple complex of Gonur Depe (Figure 1). It represents one of more than twenty small settlements surrounding this proto-urban centre. Two of them—Gonur 20 and 21—were first excavated in 2010 and 2011. The excavations revealed that the settlements differ in layout and, possibly, also in specialisation. Gonur 20 comprised ovens, kilns, residential construction, household zones and more than 70 human and animal tombs (cists, shafts and ground pits). One specific trait of the site is the presence of rare fragments of steppe pottery and buildings not typical of a Margiana oasis. Perhaps this is one of the few examples of evidence for interaction between farmers and mobile cattle breeders in south-eastern Turkmenistan (Sarianidi & Dubova Reference Sarianidi, Dubova and Sarianidi2012).

In spring 2019, excavations of the south-western part of the site were undertaken (excavation area 2); no traces of residential buildings were found. To the west of room 15, eight tombs were discovered (one cist and five shaft tombs, one burial in a sarcophagus—formed by two large jars—and one pit combined with a cist) together with four separate and different features, two commemorative pits containing only pottery and two empty pits (Figure 2). The area to the west of the residential buildings was occupied by ordinary graves containing small assemblages of one to two vessels.

Figure 2. Excavations at Gonur 20 in 2019: general site view; grave numbers are shown in black squares (photograph by A. Fribus).

Only tomb 78 stands out from the others because of its atypical structure (Figure 3). The burial pit had a sub-rectangular form and was divided by a mud-brick wall into two parts. Fragments of several jars were placed on the top of this wall. The eastern part of the tomb contained a small cist with 11 ceramic vessels of various shapes. The western side was occupied by a female skeleton. The woman was laid on her right side in a crouched position, head oriented to the north-west. There were five ceramic vessels positioned to the west of the body, including a rare, large round-bottomed vessel decorated with horizontal red stripes. The assemblage included a stone biconical bead, a metal seal and a bronze hairpin decorated with turquoise and lapis lazuli beads and a miniature limestone human foot. The remnants of a wooden item (perhaps a box cover or plaquette), plastered with lime-sand mortar and covered by the polychrome painting, were found in the south-east part of the pit.

Figure 3. Gonur 20, grave 78, general view (photograph by A. Fribus).

Polychrome painting

The upper part of the item measured 0.22 × 0.17m. The wooden base was partly preserved owing to having been treated with a preservative and possibly due to the nature of the wood. It showed weakly expressed growth rings, which is not typical for species growing in the Murghab Oasis. After the item's wooden base collapsed, most of the images were inverted by the slumping and remained upside down until discovery. The plaquette was removed from the grave as a block using a special temporary conservation technique (Figure 4). It was transferred to the Mary Historical Museum where a conservation team from Russia and Turkmenistan will begin conservation work.

Figure 4. Gonur 20, grave 78, showing the process of the excavation; conservation of the painting fragment was undertaken by Mered Rzakov (Mary History Museum) and Muhametnazar Begliev (photograph by A. Fribus).

As the main part of the painting was upside down and therefore not visible during the excavation, and because it needs very careful cleaning, the full composition is not obvious. Initial examination of several fragments suggests that three coloured dyes were used: black, red and ochre-brown. Some fragments are covered by a schematic representation of an anthropomorphic figure. Its head is represented by a circle, the left hand is bent and rests on the waist, the right hand is extended forward and holds what may be a snake. The human figure is drawn using black paint; there are also circles of red and brown, the meanings of which are as yet unclear (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Gonur 20, grave 78, the polychrome painting in situ (photograph by A. Fribus).

A large series of unique items, made using the combined techniques of mosaic and polychrome painting, is known from Gonur Depe (Sarianidi & Dubova Reference Sarianidi, Dubova, Kolganova, Petrov and Kullanda2013). Several mosaics were found at Togolok 1 and the Large Gonur Necropolis as early as the 1990s (Sarianidi Reference Sarianidi2002). The discovery in 2004 and 2009 of mosaic compositions at the Royal Necropolis can be considered sensational. There they decorated the facades of underground tombs and massive wooden caskets. Among the objects found there were several ornamental motifs as well as unique intricate compositions (pairs of fighting griffins; griffin in the cartouch; snakes swallowing goats; winged dragons fighting with snakes) (Figure 6). Anthropomorphic representations were not preserved, but, taking into account numerous stone inlays in the form of eyes, they were present. Only one portrait mosaic, originating from tomb 3245, is known. While anthropomorphic images are widely present on glyptic art—the motive of the hero and the snake for example is often presented on seals, although its meaning is not always clear—they are very rare on drawings and mosaics from Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex sites (Sarianidi Reference Sarianidi1998).

Figure 6. Samples of mosaic made with mixed techniques at Gonur Depe: а) lateral face of the casket from the hypogeum 3880; b) mosaic composition ‘griffin in the cartouch’ from the hypogeum 3210; c) fragments of the portrait from tomb 3245; d) fragment of the composition ‘pairs of fighting griffins’ from the hypogeum 3210 (photographs © Margiana Archaeological Expedition).

Conclusion

The painting found inside the tomb at Gonur 20 is the first polychrome painting on Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex territory. Comprehensive study of the artefact, including analysis of the technique of image application, the composition and nature of colouring pigments and radiocarbon dating of wood samples, will allow us to reconstruct ancient technologies and provide new data on the objects and themes of Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex art. Once the artefact has been conserved and its composition has been reconstructed, it will provide important new information concerning the interaction between Old World civilisations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Marina Karapetian (Lomonosov Moscow State University) for proofreading the manuscript. The research was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant number: 18-09-40082).