Introduction

Several recent European elections, including the 2019 Danish and Austrian elections, brought losses for radical-right challenger parties, and reinvigorated mainstream parties. Political commentary suggested (see, for example, Duxbury, Reference Duxbury2019), this development was due to mainstream parties’ tougher stances on immigration stemming the loss of voters to radical-right parties. In this narrative, mainstream party accommodation is successful, and thus a means to oppose an electoral threat from challenger parties (see Eatwell and Goodwin, Reference Eatwell and Goodwin2018). Recent research has suggested that this narrative is not entirely accurate, as it fails to grasp the complexity of electoral dynamics on party- and individual-levels (Abou-Chadi and Wagner, Reference Abou-Chadi and Wagner2020; Hadj Abdou et al., Reference Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes2021; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021). It assumes the increased public salience of an issue is driven exclusively by a challenger party and media reporting, while mainstream party accommodative strategies are inconsequential regarding voter attention to the challenger issue.

However, research has indicated that some political parties, such as incumbent parties, are more capable of driving media than less established parties (Schoenbach and Semetko, Reference Schoenbach and Semetko1996; Semetko and Valkenburg, Reference Semetko and Valkenburg2000). Further, literature has shown that party relevance (see Sartori, Reference Sartori2005), is also important for driving media attention on issues (Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann2012). Extended, this research suggests that mainstream party accommodation of challenger issues may play an important role in driving public salience of the challenger issue. In fact, recent literature has suggested that, although nuanced, centre-right accommodation of the radical-right on the issue of immigration drives voters towards the radical right. This is theorized to occur due to the increased salience of the issue (see Hadj Abdou et al., Reference Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes2021).

Our study assesses the relationship between issue salience and challenger-mainstream interactions by examining how individual concern regarding a challenger issue is driven by mainstream reactions to challenger parties. While challenger parties may directly drive an increase in the salience of their owned issues, we argue, in line with existing research on the advantage some parties hold in attracting attention (Semetko and Boomgaarden, Reference Semetko and Boomgaarden2007; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann, de Vreese and Albæk2011; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann2012), that mainstream parties, through policy accommodation of challenger parties, contribute to changes in public salience of challenger issues. This is an effect previously overlooked by the media, politicians, and academics alike, and potentially diametrical to the intention of mainstream parties.

Specifically, we contend that beyond a challenger party’s ability to directly affect the public salience of an issue, a challenger’s impact depends, to a degree, on whether a mainstream party accommodates challenger issues, rather than employs a dismissive strategy (see Meguid, Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008).Footnote 1 We propose a process in which challenger parties increase both the public salience of their owned issues and voters’ positive attitudes towards a challenger party by affecting mainstream party issue positions. Mainstream parties accommodating challenger parties (i.e., positioning themselves close to the position of challengers) garners greater attention for the challenger issue, thus increasing public salienceFootnote 2 of that issue, and potentially influencing public positivity of a challenger party.

From our theory, we derive three hypotheses. First, the more a challenger party discusses an issue, the more salient the issue becomes to the public. Second, when mainstream parties accommodate a challenger party’s issue position, public salience of that issue will be greater. Third, when mainstream parties accommodate a challenger, the public will hold a more positive attitude towards the challenger party.

These hypotheses are tested using party position and issue salience data from the Manifesto Project (MARPOR, Volkens et al., Reference Volkens2021 and individual-level data from the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES, 2018). While challenger parties can exist in multiple different party families, we focus on radical-right parties, as they are quintessential challengers that own a specific issue, immigration.Footnote 3

Radical-right parties have politicized new issues (e.g., immigration) that cross-cut existing cleavages (De Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012). They also have the ability to influence mainstream parties’ behavior, with mainstream parties often accommodating radical-right positions, thus situating themselves closer to the radical-right (Meguid, Reference Meguid2008; van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2010; Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, de Lange and van der Brug2014; Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017). The recent rise of radical-right parties and the growth of the immigration issue in European politics, thus provides us with an ideal case to test our propositions about challenger parties and issues, allowing us to understand the mechanisms by which challenger parties influence the public.Footnote 4

We find that radical-right party emphasis on immigration is associated with greater public salience regarding immigration, and that mainstream accommodation is associated with radical-right party issues being of greater individual concern. When center-right or center-left parties, respectively, in a country hold positions more similar to radical-right parties on immigration, individuals are more likely to view immigration as a most important problem facing the country. While this process appears to be intuitive, and, in fact has been assumed in a substantial amount of literature on the effects of mainstream party accommodation of challenger parties (see Krause et al., Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2019; Meijers and Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020; Hutter and Kriesi, Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021), it has never before been demonstrated. This study, however, seeks to specifically test this commonly spelled out assumption.

Our approach contributes to previous literature on mainstream party strategies and accommodation of challengers, and its effects on voters. By using direct individual measures of issue salience and attitudes towards challenger parties instead of aggregate vote shares, this study provides a clearer perception of the direct effects of mainstream party accommodation. Additionally, our approach allows for controlling for individual characteristics.

Challenger parties, issue entrepreneurship, and issue ownership

Issue entrepreneurship theory posits that parties seek new issues, particularly when they have experienced repeated electoral defeats (Carmines and Stimson, Reference Carmines and Stimson1989). Furthermore, certain conditions, for instance a party’s status as challenger, reinforce a party’s incentives for issue entrepreneurship. For challenger parties, politicizing new issues that cross-cut existing cleavages generates opportunities to form coalitions, avoiding exclusion from government (de Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012; Hobolt and de Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015).

But how do challenger parties increase political contestation over an issue? What is the process through which challenger parties boost public salience of new issues? The existing literature on challenger parties increasing the politicization of a new issue (i.e., working as issue entrepreneurs) indicates that challenger parties will increase discussion of an issue that has previously not been politicized. This will draw public attention to the issue, thus increasing its salience among the public (de Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012; Hobolt and de Vries, Reference Hobolt and De Vries2015; Green-Pedersen and Otjes, Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2019). Following this literature indicating that increased focus on an issue by challenger parties increases the politicization of that issue, and therefore the public salience of that issue, we hypothesize:

H1: The more a challenger party discusses an issue, the more salient that issue will become among the public.

Importantly, while the extant literature has shown that challenger parties can influence public salience of issues through focusing attention on those issues, it has not examined a more indirect mechanism: challenger parties may influence an issue’s public salience by influencing mainstream party positions.

Challenger parties cause electoral threats to mainstream parties by politicizing and establishing ownership of issues previously neglected by mainstream parties (de Vries and Hobolt, Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012; Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2012), thus acting as issue entrepreneurs with (associative) issue ownership. For example, radical-right parties have brought immigration to the political agenda, and they are seen as issue owners (Mudde, Reference Mudde2010). This results in mainstream parties fearing a loss of voters to these challengers (Bischof, Reference Bischof2017).

Mainstream parties may react in three ways to challenger parties and their issues (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008): (1) they can ignore the competition and remain passive; (2) they can accommodate the challenger’s position, moving closer to it; (3) they can take an adversarial stance. While mainstream party reactions are context-dependent, myriad literature suggests that mainstream parties often choose accommodation, particularly for radical-right parties (van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2010; Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, de Lange and van der Brug2014; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Williams and Ishiyama, Reference Williams and Ishiyama2018).

While most studies have focused on the ‘when’ and ‘where’ of mainstream party accommodation (see Green-Pedersen and Mortensen, Reference Green-Pedersen and Mortensen2010; Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016), we are interested in the consequences of mainstream party accommodation of challengers, and specifically, radical-right parties. Some previous studies have, however, assessed the question whether an accommodative strategy might be beneficial for mainstream parties, thereby focusing on vote switching (Spoon and Klüver, Reference Spoon and Klüver2020) or propensity to vote (Hjorth and Larsen, Reference Hjorth and Larsen2020) as dependent variables. Spoon and Klüver (Reference Spoon and Klüver2020) show that despite mainstream parties’ positional shift to the right, voters would rather turn out for “the original”, i.e., the radical-right wing challenger. Focusing on the mainstream left and using a survey experiment in Denmark, Hjorth and Larsen (Reference Hjorth and Larsen2020) show vote switching from former radical-right voters, but losses to parties more on the left, however still resulting in net gains.

Along similar lines, we argue that this accommodation increases the public salience of the challenger issue (immigration in the case of the radical-right) further. Deviating from previous scholarship, we use two different outcomes that, as we argue, can provide additional insights: public concern of immigration issues and positivity towards the radical-right challenger. Unlike vote choice, which requires a complete defection from mainstream parties, these two outcomes enable us to study attitudes that might preempt voting for a radical-right party. Furthermore, these two outcomes of mainstream party accommodation can be distinguished since public concern is rather programmatic, while positivity towards the challenger points more towards an affective closeness to the party.

Due to their status as established parties and contenders to serve in government, mainstream parties more easily garner public attention than challenger parties (Meguid, Reference Meguid2005, Reference Meguid2008; Hopmann et al., Reference Hopmann2012; Meyer and Wagner, Reference Meyer and Wagner2013). Previous studies have shown the central role of mainstream parties in increasing the visibility of challenger issues, and immigration specifically (van der Brug et al., Reference van der Brug, D’Amato, Ruedin and Berkhout2015; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019), particularly of center-right parties (Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup, Reference Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup2008).

Furthermore, a long tradition in political psychology research has shed light on the underlying mechanisms through its study of partisans’ cue-taking (see e.g., Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1980). A rich strand of literature has demonstrated that party cues serve as a heuristic and thus shape citizens’ assessments of policy issues – particularly individuals with less political knowledge or knowledge on the issue (Kam, Reference Kam2005; Bullock, Reference Bullock2011). Partisans’ perceptual gaps, i.e., how they assess a political situation such as the state of the economy, is shaped by elite cues to (Bisgaard and Slothuus, Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018) and even when it comes to ‘highly salient issues with clear ideological connotations’ (Slothuus and Bisgaard, Reference Slothuus and Bisgaard2021). This ties in well with our theoretical argument. Consequently, if parties with the most voters shift their positions on an issue, e.g., immigration, we argue in line with theories on cue-taking that this will shift individual concern regarding immigration. Thus, a mainstream party accommodating the challenger’s position should result in greater public attention for the issue.Footnote 5 Thus, it can be hypothesized:

H2: When mainstream parties accommodate the position of a challenger party on an issue, the challenger issue will be more salient.

While this implies that voters become more attentive to the core issue of radical-right parties when mainstream parties take similar stances on the issue, we ask whether this might also lead to more positivity towards the radical-right party? Research has indicated that rising salience of a challenger issue is associated with a greater vote share for the challenger. For example, Abou-Chadi (Reference Abou-Chadi2016) suggests that mainstream party shifts towards the position of a challenger will increase the challenger’s vote share. This presupposes that accommodation increases the salience of the challenger issue. Similarly, Krause et al. (Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2019) and Meijers and Williams (Reference Meijers and Williams2020) find that mainstream party accommodation of challenger issues leads to challenger parties gaining vote share, and mainstream parties losing vote share. Further, Hutter and Kriesi (Reference Hutter and Kriesi2021) show that radical-right parties benefited from centre-right emphasis and accommodation. Finally, Spoon and Klüver (Reference Spoon and Klüver2020) found greater vote switching to the challenger party as a result of mainstream party accommodation of challengers.

Taken together, this research indicates that increasing salience of a challenger issue appears to produce a greater propensity to vote for the challenger party. These findings may well indicate that increased salience of a challenger issue, which we expect to partly derive from mainstream party accommodation, produces greater positivity towards that party amongst the public.

In fact, it follows that increasing salience of a challenger issue would produce greater positivity towards the challenger party. As salience of an issue increases, the public is more likely to view that issue as a problem (see Jennings and Wlezien, Reference Jennings and Wlezien2011). If an individual views an issue as a problem, they should prefer the party that has established ownership of that issue, which in the case of a challenger issue, is the challenger party. In the words of French radical-right leader Marine Le Pen, voters will ‘simply prefer the original’ (Arzheimer and Carter, Reference Arzheimer and Carter2006; Dahlström and Sundell, Reference Dahlström and Sundell2012).

Thus, we argue that once mainstream parties accommodate challenger party positions, voters will attach more importance to the challenger issue, and will feel greater positive affect towards the ‘original’ party, meaning the issue-owning challenger. Hence, we propose:

H3: When mainstream parties accommodate the position of a challenger party, voters’ positivity towards the challenger party will be greater.

Data and case selection

To test the above hypotheses, we focus on radical-right parties, as quintessential challengers. Radical-right challenger parties are quite united in their politicization of immigration (Ivarsflaten, Reference Ivarsflaten2008) and established associative ownership of the issue (Walgrave et al., Reference Walgrave, Lefevere and Tresch2012, 779; see also Mudde, Reference Mudde2010). Therefore, we examine how mainstream party accommodation of challenger immigration positions influences individual-level immigration salience of the issue and positivity towards challenger parties. In the next section, we discuss our data sources, the operationalization of our variables, and case selection (i.e., countries included).

Individual-level data

This study focuses on two individual-level dependent variables: individual perceptions of the importance of the immigration issue for a country and individual positivity towards a radical-right party. We operationalize these variables using the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems data (CSES, 2018), which provide measures of individual attitudes across many countries.

For individual immigration salience, we use two nearly identical questions, which were asked in modules 2 (2001–2006) and 3 (2006–2011) of the CSES. In module 2, respondents were asked which issue they perceived as most important for their country during the last legislative period. Similarly, respondents in module 3 were asked for the most and second most important issue.Footnote 6 We treat individual concern regarding immigration as dichotomous where 1 indicates a respondent mentioned immigration as a most important issue.

The dependent variable for hypothesis 3 is a voter’s attitude towards a radical-right party. In all CSES modules respondents were asked to provide a degree of positivity towards each radical-right party of interest. This variable ranges from 0 (strongly dislike) to 10 (strongly like).

Party-level data

While the dependent variables are individual-level, the main independent variables of this study are located at the party-level. The independent variable used in testing hypothesis 1 is overall radical-right party discussion of immigration (i.e., immigration salience). Following recent research on mainstream party accommodation (Meijers and Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020), the independent variable for hypotheses 2 and 3 is the distance between the mainstream party position and the radical-right party position on immigration.Footnote 7 Measures of these variables are derived from the Comparative Manifesto Project (MARPOR, Volkens et al., Reference Volkens2021).Footnote 8

Our immigration measures are operationalized using statements regarding a ‘National way of life’ (positive [per601] and negative [per602]) and ‘Multiculturalism’ (positive [per607] and negative [per608]) (Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Vrânceanu and Lachat, Reference Vrânceanu and Lachat2018). For salience, we use the percentage of sentences dedicated to immigration in a manifesto. For a party’s position on immigration, we subtract the log of anti-immigration statements from the log of pro-immigration statements (Lowe et al., Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011),Footnote 9 thus, a lower value indicates a more anti-immigration position. To calculate the distance between a mainstream party immigration position and a radical-right party immigration position, we subtract the radical-right position from the mainstream party position, with higher values indicating greater distance.

Case selection

Our analyses include 15 elections in 8 European countries (Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, and Switzerland) between 2001 and 2011.Footnote 10 These cases allow us to test our proposed mechanism in countries with established radical-right partiesFootnote 11 that serve as challenger parties in these political systems.Footnote 12 Further, the time period is determined by data availability for radical-right parties’ and mainstream parties’ immigration salience and positions across elections, as well as individual positivity towards the challenger parties (used to test hypothesis 3).

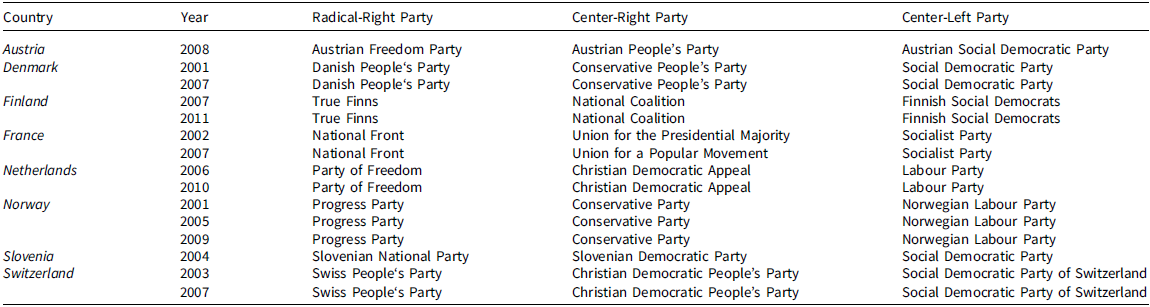

In order to test the above hypotheses, we must determine whether a party is a radical-right party or a mainstream party. We classify the radical-right and mainstream parties in our sample based on MARPOR, ParlGov (Döring and Manow, Reference Döring and Manow2018), and PopuList (Rooduijn et al., Reference Rooduijn, Van Kessel, Froio, Pirro, De Lange, Halikiopoulou, Lewis, Mudde and Taggart2019).Footnote 13 Following research (Meijers and Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020) indicating that electoral strength is necessary for a challenger to establish issue ownership, we focus on the radical-right party with the highest average vote share since 2001, thus, it is possible that a radical-right party does not have the largest vote share in any one given election, but is the largest average vote receiver.Footnote 14 Similarly, we focus on the effect of the largest center-right and center-left parties’ accommodative strategy in a country (Table 1).

Table 1. Countries and elections included in analyses

Analytical strategy

The dependent variable for individual-level concern regarding immigration is dichotomous. If an individual named immigration as a most important problem in their country in an election-year, they were coded with a value of 1; otherwise, they were coded as a 0.Footnote 15 The main independent variable used for radical-right party discussion of the immigration issue (i.e., party immigration salience) is operationalized as the percentage of a radical-right party’s manifesto that is dedicated to immigration. Following previous literature (Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Vrânceanu and Lachat, Reference Vrânceanu and Lachat2018), sections in manifestos concerning immigration are understood to be those sections focused on ‘National way of life’ (positive [per601] and negative [per602]) and ‘Multiculturalism’ (positive [per607] and negative [per608]).

Hypothesis 2 posits that when mainstream parties accommodate a challenger party, the public will view the challenger’s issue as more important. In testing this hypothesis, we include a measure of mainstream party position relative to the radical-right party position in our model. This is operationalized as the difference between a mainstream party’s and a radical-right party’s position. A positive value indicates the mainstream party is more positive towards immigration than the radical-right party.

As stated above, we examine the effects of center-right and center-left mainstream party proximity to the radical-right position. We conducted two separate tests, one with center-right and one with center-left party proximity as the main independent variable. We think this analysis is valuable for a number of reasons. First, center-right and center-left differ in their success of bringing radical-right issues further to the center-stage of the political agenda. Second, as we know from political psychology research, partisans’ cue taking might not only differ depending on the individual level traits (Kam Reference Kam2005; Bullock, Reference Bullock2011) but also on parties’ attributes such as party age, government status, and the ideological clarity of the party’s cues (Brader and Tucker, Reference Brader and Tucker2012). This also applies to so-called ‘out-party cues’ (Goren et al., Reference Goren, Federico and Kittilson2009). Along these lines, Bischof and Wagner (Reference Bischof and Wagner2019) find that radical-right parties’ entry to parliament has a legitimizing effect on more right-wing individuals and a back-lash effect on more left-wing individuals, thus in tandem leading to voters’ polarization. In essence, it is not only possible, but likely that centre-left and centre-right proximity have differing effects, if not in direction, certainly degree, on the public salience of the immigration issues. Thus, it is important to study the effect on mainstream left and right accommodation separately.Footnote 16 Hypothesis 3 argues that when mainstream parties accommodate a challenger party position, the public will be more positive towards the challenger party. The dependent variable for this hypothesis is individual-level positivity towards a radical-right party. The main independent variable used in testing hypothesis 3 is mainstream party position relative to radical-right party position. This is operationalized in the same manner as for the tests of hypothesis 2.

The data in this study are structured to reduce the possibility that mainstream parties are simply ‘riding the wave,’ which posits that it is (electorally) beneficial for parties to ‘jump’ on issues that are already on voters’ minds (Ansolabehere and Iyengar, Reference Ansolabehere and Iyengar1994). In essence, when parties ‘ride the wave,’ they begin focusing on the issues that the public is most concerned with, rather than attempting to focus public attention on a different issue. This should result in increased vote share. Our data are temporally structured, with our main independent variables measured through manifestos, prior to when our main dependent variable is measured through post-election surveys. Further, we measure public issue salience at the individual-level. It is highly unlikely that one individual’s attitude will influence the position of a party on an issue, or the degree to which a party discusses an issue.

While the structuring of the data reduces the likelihood that public opinion is driving party discussion and positions in our data, we still control for the possibility that parties are simply adjusting their positions to ‘ride the wave’ of public opinion. Additionally, to our measure of mainstream parties’ positional proximity to radical-right parties, we include a measure of change in mainstream party position on immigration between the election at time t −1 and the election at time t 0 . This measure picks up change in position, which is a requirement of the ‘riding the wave’ strategy. Thus, a null result for this measure would indicate that the increased public salience of immigration is not systematically driving mainstream parties to change their position on the issue.

Put differently, including both the proximity of mainstream parties’ positions to those of the radical-right party in a given party system allows us to include measures of movement and proximity, i.e., accommodation. Taken in tandem, our results for the proximity measure can be interpreted as the association between mainstream parties’ accommodation and changes in public opinion, while holding the sole change in salience constant.

A mainstream party’s position is measured as the log of pro-immigration statements minus the log of anti-immigration positions. Thus, a smaller value indicates a party holds a more anti-immigration position. For models which include the distance between radical-right and center-right immigration positions, and radical-right and center-left immigration positions, we include a measure of change in center-right position and center-left position, respectively, between two elections. We do not include a measure of mainstream party immigration position change for models that do not include the difference in position between the radical-right and a mainstream party.

All models also include controls for individual left-right self-placement, age, sex, education level, marital status, self-reported income, and urbanity for all respondents. Left-right self-placement is a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being furthest right. Age is measured in years. Sex is dichotomous (1 for males). Education is ordered, ranging from 0 (no education) to 4 (university degree or higher). Marital status is dichotomous (1 if an individual is married). Income is ordered, ranging from 1 (lowest income quintile) to 5. Urbanity is dichotomous (1 for living in a rural community). Additionally, we control for whether respondents live in an Eastern European or non-EU country, and whether the observation comes from CSES module 2.

Finally, we control for party system salience of immigration.Footnote 17 This variable is operationalized as the average immigration salience among all the parties in a system, weighted by party vote share. In tests of hypothesis 1, in which only radical-right party salience is included as a main independent variable, we include a measure of party system immigration salience for all parties in the system that are not the radical-right party. For hypotheses 2 and 3, which include the distance in position between radical-right and center-right, and center-left parties, respectively, the party system immigration salience variable excludes both the radical-right party and the focal center-right or center-left mainstream party identified in Table 1.Footnote 18

As the dependent variable for hypotheses 1 and 2 is dichotomous, the most appropriate approach is logistic regression. The dependent variable for hypothesis 3 approximates a continuous variable, thus we use OLS regression. Our data consist of individuals nested within countries in specific election-years, and we include variables at multiple levels of analysis (individual and party-system). Thus, we use multilevel mixed effects models with random intercepts by country-election.

Findings

We start with discussing the regression analyses that test our hypotheses. Model 1 (Table 2) includes radical-right party immigration salience as the main independent variable and is a direct test of hypothesis 1. The positive and statistically significant coefficient for the main independent variable in models 1 through 3 indicates that when the radical-right party in a country discusses immigration to a greater degree, the likelihood of an individual in that country believing immigration to be a most important problem is greater.Footnote 19 These findings fit with existing literature showing that challenger parties can drive public salience of issues, and specifically that radical-right parties can drive public attitudes on immigration (Green-Pedersen and Otjes, Reference Green-Pedersen and Otjes2019; Grande et al., Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019). The intraclass correlation coefficient for this model is 0.08, indicating the effects of the independent variable and controls are not highly dependent upon the cluster an individual is in.

Table 2. Effects of radical-right salience and mainstream proximity on public immigration salience

***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05.

In order to further present and qualify these findings, we present several figures that dive deeper in the results of models 1 to 3. Figure 1 (drawing in model 1) shows the substantive effects of radical-right party immigration salience on the likelihood that an individual perceives immigration as a most important problem while holding all other variables at their mean or median. The x-axis depicts the percentage of the radical-right party’s manifesto dedicated to immigration. The y-axis displays the likelihood that an individual views immigration as a most important problem. The solid black line indicates the expected likelihood of an individual viewing immigration as a most important problem, while the gray area is the 95% confidence interval. The black tick marks represent the distribution of radical-right party immigration discussion.

Figure 1. Effect of Radical-Right Party Discussion of Immigration on Public Salience. Note: Figure 1 is based on the results of Model 1.

When the emphasis on the immigration issue in a radical-right party’s manifesto is greater, the likelihood that an individual views the issue of immigration as a most important problem is also likely. If a radical-right party does not discuss immigration at all, the expected likelihood of an individual viewing the immigration issue as a most important problem is nearly 0. However, when the radical-right party’s discussion of immigration is 10% (about the sample median), the likelihood of an individual viewing immigration as a most important problem is about 0.10. When radical-right party immigration salience is 40%, the likelihood of an individual viewing immigration as the most important problem is about 0.45.

Importantly, one should be cognizant of the relatively few observations in which radical-right party immigration discussion is greater than 30 (only 5 observations in the dataset). Due to the small number of observations at this level, the confidence interval is extremely large at these levels. This indicates that when radical-right party immigration salience is 40%, the likelihood of an individual viewing immigration as the most important problem may be as low as 0.15 or as high as 0.65. Despite this large confidence interval, however, the lower bound of this confidence interval at high levels of radical-right immigration salience is still greater than the upper bound at the lower level of radical-right immigration salience. Thus, the results reported in Figure 1, combined with the findings reported in Model 1 support hypothesis 1.

Model 2 (Table 2) includes center-right mainstream party proximity to the radical-right party’s position as an additional independent variable. Thus, the model allows us to test hypothesis 2 which posits that mainstream party accommodation is associated with an increased immigration salience. The intraclass correlation coefficient is 0.04, indicating the effects of the independent variables are not driven by the nested structure of the data. The coefficient for center-right party position proximity to the radical-right party position on immigration is negative (the expected direction) and statistically significant. This suggests that when center-right parties position themselves further from the position of radical-right parties on immigration, individuals are less likely to view immigration as a most important problem. This supports hypothesis 2. Importantly, the change in center-right mainstream party immigration position is statistically insignificant. This indicates that mainstream parties are not simply ‘riding the wave,’ and taken with the finding for the measure of center-right proximity to the radical-right immigration position, this suggests that a center-right party taking an immigration position more proximal to the radical-right influences public attitudes towards immigration.

To further examine these results, we plot the marginal effects for the proximity of center-right party position on immigration to the radical-right party (see Figure 2a–2c). We hold all other variables in the model at their means or medians, however, given the important role of radical-right party immigration salience in this model, we plotted the effect of centre-right party proximity to the radical-right while holding radical-right immigration salience at various levels (low, medium, and high).Footnote 20 This allows us to depict how the association between mainstream party accommodation and public salience of immigration plays across different scenarios of how much attention radical-right parties give to the immigration issue. Figure 2a holds radical-right party immigration salience at 1.706 (the lowest in the dataset), Figure 2b holds it at 15 (close to the mean for the data), and Figure 2c holds it at 30. In all cases, radical-right accommodation by the largest center-right party results in a higher likelihood that an individual views immigration as a most important problem. These figures suggest that while radical-right party immigration salience matters for the magnitude of the effect of centre-right party proximity, it does not change the direction or significance of the effect.

Figures 2. (a) Low RRP Salience (1.706); (b) Medium RRP Salience (15); (c) High RRP Salience (30). (a)–(c) Effects of Distance Between Center-Right and Radical-Right Parties on Public Salience (Based on model 2).

Figure 2a, which holds radical-right party salience of the immigration issue at 1.706, shows that when a center-right party holds the exact same position as the radical-right party, the expected likelihood that an individual in that country views immigration as a most important problem (MIP) is about 0.06. This is a low likelihood and the effect decreases rapidly as the largest center-right party in a country moves away from the position of the radical-right party. If the distance between a center-right party and a radical-right party is 2.00, close to the mean for the variable, the likelihood an individual views immigration as a most important problem is about 0.02.

Figure 2b holds radical-right party salience at 15, showing that the likelihood of an individual viewing immigration as a most important problem reaches about 0.39 when there is no distance between the center-right and radical-right parties. Further, when radical-right party immigration salience is greater, the expected effect of center-right mainstream party proximity to radical-right immigration positions becomes more gradual. The center-right’s proximity to the radical-right party becomes less influential on the likelihood that an individual views immigration as a most important problem, although it remains substantively important.

Figure 2c, which holds radical-right party salience at 30, indicates that a center-right party being closer to the radical-right party is associated with a likelihood of an individual perceiving immigration as a most important problem in a country of nearly 0.90. Again, this association become less influential with increasing levels of radical-right party immigration salience, but remains substantively significant.

As with Figure 1, one should be cognizant of the large confidence interval surrounding the point estimates reported in the Figure 2a–2c, particularly when the distance between a centre-right and radical-right party is greater. For example, in Figure 2c when the distance between a centre-right and radical-right party is 0, the confidence interval ranges from about 0.65 to about 0.95.

However, even if one were to assume that the lower bound of the confidence interval were more accurate, these findings suggest that center-right parties play an important role in increasing the salience of radical-right party issues. If center-right parties accommodate radical-right parties on immigration, public salience of the issue is greater. The extent of that effect, however, is influenced by the salience of immigration to the radical-right party. When radical-right parties’ immigration salience is low, a center-right party taking a position similar to the radical-right party on immigration shows a relative increase in public salience of immigration, but public salience of immigration remains low in absolute terms. When radical-right parties make immigration the cornerstone of their appeal, accommodation by center-right parties is associated with relative increases in public salience of immigration, as well as high absolute public salience.

In Model 3 (Table 2), we include the distance between the largest center-left mainstream party and the radical-right party. The intraclass correlation coefficient for this model is 0.05, indicating the effect of the main independent and control variables are not dependent upon the cluster the individuals are grouped in.

The coefficient for center-left proximity to the radical-right’s position is statistically significant and negative (the expected direction). This indicates that when the largest center-left party in a system is closer to the radical-right party’s immigration position in a country, individuals are more likely to view immigration as a most important problem. Taken with the finding in Model 2, this indicates support for hypothesis 2.

We present the substantive results of Model 3 in Figure 3a–3c. As with Figure 2a–2c, these figures show the marginal effects for the proximity of the center-left party’s position on immigration to the radical-right party’s position while holding all variables, except radical-right party salience of the immigration issue, at their means or medians. In Figure 3.1 through to 3.3, radical-right party salience is held at the same levels as it is in Figure 2a–2c. In all cases, radical-right accommodation by the largest center-left party results in a higher likelihood that an individual views immigration as a most important problem. These figures suggest, while radical-right party immigration salience matters for the magnitude of the effect of centre-left party proximity, it does not change the direction or significance of the effect.

Figures 3. (a–c) Effects of Distance Between Center-Left and Radical-Right Parties on Public Salience (Based on model 3).

Figure 3.1 indicates, given low radical-right party immigration salience, that an individual’s likelihood of viewing immigration as a most important problem facing their country is higher if a center-left party holds a position closer to the radical-right party. However, the likelihood of an individual viewing immigration as a most important problem is low, about 0.01.

When radical-right salience of the immigration issue is 15 (Figure 3.2), we find a more pronounced effect of center-left party proximity to the position of the radical-right. When the center-left party holds the same position as the radical-right party on the immigration issue, and immigration is moderately salient to a radical-right party, the likelihood that an individual views immigration as a most important problem facing the country is 0.45.

Figure 3.3 indicates that when center-left proximity to the radical-right position on immigration and radical-right discussion of immigration is high (here: 30%), individual concern for the immigration issue is also quite high with a likelihood of any one individual viewing immigration as a most important issue being about 0.87.

As with previous figures, the confidence intervals in Figure 3.1 through to 3.3 appear quite large, particularly when the distance between centre-left and radical-right position on immigration is close to 0. However, the effects seen in Figure 3a–3c tell a similar story to Figure 2a–2c. When a center-left party is closer to the radical-right party on immigration, public salience of immigration is greater in relative terms. However, when immigration is less salient to a radical-right party, the public salience of immigration, even when a center-left party holds the exact same position as the radical-right party, is small in absolute terms. When the immigration issue is more salient to a radical-right party, and the position of the center-left party is closer to that of the radical-right party, public salience of immigration is relatively greater, and high in absolute terms.

The findings presented in models 2 and 3, and the substantive effects reported in Figures 2a–2c and 3a–3c, support hypothesis 2. Mainstream parties taking positions more similar to radical-right parties are associated with greater public salience of immigration. This suggests that mainstream party accommodation plays an important substantive role in influencing citizen concern, when radical-right party discussion of immigration is at least at moderate levels.

Models 4 and 5 (Table 3) examine the effect of radical-right party immigration salience and mainstream party accommodation of the radical-right immigration position on individual positivity towards the radical-right party, testing hypothesis 3 (center-right party results are reported in Model 4 and center-left party results are reported in Model 5).Footnote 21 Mainstream party proximity to the radical-right immigration position is statistically insignificant in models 4 and 5, while radical-right party salience of immigration is significant in Model 4, but not Model 5.

Table 3. Effects on positivity towards the radical-right party

***P ≤ 0.001; **P ≤ 0.01; *P ≤ 0.05.

This suggests that mainstream party accommodation of the radical-right on immigration does not influence individual positivity towards the party; the null of hypothesis 3 cannot be rejected. The intraclass correlations of 0.02 and 0.03 in models 4 and 5, respectively, indicate that the effect of the independent variables is not dependent on the individuals’ clustering.

Interestingly, change in mainstream party immigration position is statistically significant for both the center-right and the center-left. This suggests a relationship between the change in mainstream party position on immigration and individual positivity towards the radical-right. Of course, due to the data in this study, causality regarding this finding cannot be determined. It is possible, and given extant literature (see Bischof, Reference Bischof2017), some might likely argue, that mainstream parties are moving towards the radical-right because they fear the loss of voters to a radical-right party. However, it is also possible that movement of mainstream parties towards the radical-right is driving positivity towards the radical-right. This relationship should be investigated further at the individual level.

Regarding controls, an individual’s left-right self-placement is statistically significant and positive in models 1 through to 5, indicating that people further to the right are more likely to see immigration as an important issue, and are also more likely to view radical-right parties more positively. Models 1 and 2 indicate a positive association between party-system immigration salience and an individual’s likelihood of viewing immigration as a most important issue. Individuals in non-EU countries are found to be more likely to view immigration as a most important problem in models 1 through to 3, but they are found to only be more positive towards radical-right parties in Model 4, which concerns center-right parties. Individuals who were interviewed in module 2 of the CSES were less likely to view immigration as a most important problem in models 1 through to 3, and were more positive towards radical-right parties only in Model 4.

No other controls were statistically significant in models 1 through to 3, however, all individual-level controls were statistically significant in models 4 and 5. In addition to the left-right self-placement leading to greater positivity towards radical-right parties, men, married individuals, and those living in rural areas were more positive towards radical-right parties, while older, more educated, and higher income individuals were less positive towards radical-right parties.

Discussion

This study sought to understand the vector by which challenger party issue entrepreneurship influences individual concern about that issue, as well as individual positivity towards these parties. We posited that, apart from the direct effect of challenger parties’ politicization on public attitudes, there is an indirect accommodation effect as well. Examining radical-right parties, as they are quintessential challengers that influence mainstream party positions, we find that mainstream accommodation of challenger parties does influence the public salience of challenger issues.

Specifically, our findings suggest that radical-right party immigration salience positively affects individual concern regarding the issue. We also find strong evidence that mainstream accommodation of radical-right party positions is associated with higher levels of public salience. In fact, our results indicate that this accommodation is closely linked to the degree to which individuals are concerned with immigration, especially in cases of moderate or high radical-right party immigration salience. Moreover, we find that the effect is substantively similar for center-left and center-right accommodation of radical-right positions. We find no evidence suggesting that mainstream party accommodation of radical-right party immigration positions influences individual positivity towards radical-right parties.

These findings have important implications for the study of party competition. Myriad literature has demonstrated that mainstream parties adapt their policy profile in the face of challenger parties (see van Spanje, Reference van Spanje2010; Schumacher and van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016; Meijers, Reference Meijers2017; Williams and Ishiyama, Reference Williams and Ishiyama2018, among others) and the evidence regarding accommodation of green party positions is less clear than the research on radical-right parties (see Spoon et al., Reference Spoon, Hobolt and de Vries2014; Abou-Chadi, Reference Abou-Chadi2016). Our findings indicate that the decision of mainstream parties to take positions similar to those of challenger parties has substantial effects on public attitudes, which may well influence voter decisions.

Importantly, our results indicate that public positivity towards radical-right parties does not increase with mainstream accommodation. However, this does not necessarily mean that accommodation does not increase an individual’s propensity to vote for the radical-right. It is possible that increased salience of a challenger party issue does not result in increased absolute positivity towards challenger parties, but greater positivity relative to other parties in the system. In fact, existing research at the aggregate level suggests that increased salience due to accommodation can drive voters away from mainstream parties (Meijers and Williams, Reference Meijers and Williams2020), and towards challenger parties (Krause et al., Reference Krause, Cohen and Abou-Chadi2019).

When the results of this study are taken in tandem with this previous literature showing that increased salience of a challenger party issue decreases votes for mainstream parties and increases votes for challenger parties, it indicates that accommodation of challenger party positions may strengthen the position of challenger parties in a system.

Further, this paper’s findings, together with the findings of Meijers and Williams (Reference Meijers and Williams2020) present evidence that indirect electoral strategies may seem successful for mainstream political parties. That is, mainstream parties may have incentives to take disingenuous positions on issues that they are not very concerned with, but will drive voters away from their largest mainstream competitor towards a challenger party.

For example, Meijers and Williams (Reference Meijers and Williams2020) find that when the salience of European integration increases in the face of a successful radical-right party, center-right parties lose votes, but center-left parties do not. If this finding holds for immigration, this suggests that center-left parties can increase the salience of immigration, not suffer electoral losses, but lead the center-right mainstream party to lose votes. Thus, these indirect electoral strategies do not maximize votes, but rather, drive voters away from a party’s main competitor. This strategy could result in a mainstream party winning the most votes and becoming more likely to form a government while not increasing (or decreasing) its own votes. Put differently, it is a winning strategy of voter retention combined with opponent torpedoing. While this strategy may be enticing to some parties, in the case of the radical-right, it must be noted, this would constitute a de-facto breach of the cordon sanitaire.

Due to the novel venue of this study, there are various additional conditioning factors that future research ought to examine. The effect of mainstream party accommodation on public concern about immigration could depend on the electoral success of the challenger party. Furthermore, current data sources do not provide us with voters’ policy preferences on immigration (we only have voters’ left-right self-placement) which might have an impact on individuals’ concern regarding the issue.

Moving forward, research on the effects of mainstream party responsiveness to challenger parties should expand the issue areas and types of challenger parties examined. It may be beneficial to examine how mainstream party accommodation of green party positions on the environment affect public salience of that issue. Moreover, as data become available through advancements in text-as-data methods, it may prove useful to examine more closely the role of media in relaying messages.

The findings regarding mainstream party accommodation and challenger party positivity should be explored in greater detail. Future research should examine the effect of mainstream party accommodation of challenger positions on changes in public positivity towards challenger parties relative to public positivity of mainstream parties. This study found that mainstream party accommodation of challenger party positions is not associated with greater positivity towards the challenger party. However, it is possible that when mainstream parties accommodate a challenger party, public positivity towards a radical-right party relative to public positivity towards a mainstream party is greater. Alternatively, future research could assess whether mainstream parties might benefit from their accommodation in terms of voters’ positivity towards the mainstream party.

Finally, while beyond the scope of this study, it may be fruitful to examine how mainstream party accommodation influences vote-choice at the individual level. It is possible that mainstream accommodation of challenger positions drives individuals to vote for the challenger, even if it does not increase positivity towards the challenger party.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773922000297.

The replication data for this article is available on HarvardDataverse under the following doi: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/D0YLVR.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the editors and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and guidance. We are grateful to Vicente Valentim, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Arndt Leininger for their help and feedback on previous versions of this paper. Additionally, our paper was greatly improved by feedback from participants and discussants at 2019 EPSA Conference as well as at the workshop ‘Public opinion and how it matters’ at the European University Institute organized by Julian Garritzmann and Mirjam Dageförde.