Impact statement

This review article examines the body of scholarly literature on polar ship-based tourism with a focus on what we know to date about the positive and negative impacts polar tourism has had, and has the potential to have, on local, regional and global systems. The article sheds light on available governance mechanisms for polar tourism and the challenges faced by policy-makers and practitioners alike in relation to polar tourism regulation and management. Open questions are explored regarding possible avenues to review and reflect on the development of polar ship-based tourism to date and its potential future sustainability, and the option of ‘degrowth’ is being explored.

Introduction: Why and why now?

Coasts are considered to be the most significant tourism destinations internationally, with coastal tourism growth peaking in the last three decades (Rangel-Buitrago et al., Reference Rangel-Buitrago, Williams, Ergin, Anfuso, Micallef, Pranzini and Rangel-Buitrago2019; Arabadzhyan et al., Reference Arabadzhyan, Figini, García, González, Lam-González and León2021). While globally most coastal tourism destinations attract visitors with their 3S (sun, sea and sand) characteristics, the Polar Regions appeal to tourists with their ‘otherness’ (Frame, Reference Frame2020; Thomas, Reference Thomas2020). Scenery is a major natural tourism asset for coastal tourism in all Köppen climate regions (Stonehouse and Snyder, Reference Stonehouse and Snyder2010; Rangel-Buitrago et al., Reference Rangel-Buitrago, Williams, Ergin, Anfuso, Micallef, Pranzini and Rangel-Buitrago2019), but due to the polar amplification of global warming (Singh et al., Reference Singh, Rasch and Rose2017; Stuecker et al., Reference Stuecker, Bitz, Armour, Proistosescu, Kang, Xie, Kim, McGregor, Zhang and Zhao2018; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Screen, Deser, Cohen, Fyfe, García-Serrano, Jung, Kattsov, Matei and Msadek2019; Cai et al., Reference Cai, Hsu and Liu2021) and the dramatic manifestations of the climate crisis in disappearing glaciers, ice-shelves and sea ice, the Polar Regions exude a sense of environmental impermanence that makes them picture-book last-chance tourism destinations (Eijgelaar et al., Reference Eijgelaar, Thaper and Peeters2010; Hall and Saarinen, Reference Hall, Saarinen, Hall and Saarinen2010; Lemelin et al., Reference Lemelin, Dawson, Stewart, Maher and Lück2010; Vila et al., Reference Vila, Costa, Angulo-Preckler, Sarda and Avila2016; Lemelin and Whipp, Reference Lemelin, Whipp and Timothy2019). In the Polar Regions, marine and coastal tourism mainly consists of cruise activities, undertaken on vessels of differing sizes and with varying levels of ice-strengthening and technological capabilities. Just like coastal tourism in other parts of the world, tourism in both Polar Regions has been growing in terms of numbers, types of activities undertaken and its impacts (Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Dowling and Weeden2017; Huijbens, Reference Huijbens, Finger and Rekvig2022).

The growth and diversification of polar tourism activities is increasingly reflected in a maturing body of scholarly literature with a shifting focus from initially descriptive accounts of tourism activities in the Polar Regions, to an exploration of management and regulation of polar tourism, to a greater number of ecological research on interactions between tourists and polar environments, to conceptual and experimental or observational studies that engage with tourism futures, tourist experiences and motivations (including last-chance tourism), place attachment, ambassadorship, and community attitudes as Arctic tourism development is concerned (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Draper and Johnston2005; Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett and Stewart2015; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Liggett and Dawson2017). With barriers to tourist entry diminishing with technological advancement and as the Polar Regions are warming and ice is retreating (Snyder, Reference Snyder, Snyder and Stonehouse2007; Herber, Reference Herber2007; Haase et al., Reference Haase, Lamers and Amelung2009; Stonehouse and Snyder, Reference Stonehouse and Snyder2010), and with visitor numbers increasing in the Arctic and Antarctic, the concept of sustainability in relation to polar tourism gains significance – both in practice and in scholarship (Lamers, Reference Lamers2009; Lamers and Amelung, Reference Lamers, Amelung, Grenier and Müller2009; Maher et al., Reference Maher, Stewart, Lück, Lück, Maher and Stewart2010; Cajiao et al., Reference Cajiao, Benayas, Tejedo and Leung2021) – in step with a need to understand the actual and potential impacts in relation to polar tourism (New Zealand, 2010; Soutullo and Ríos, Reference Soutullo and Ríos2020; Tejedo et al., Reference Tejedo, Benayas, Cajiao, Leung, De Filippo and Liggett2022).

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) represent a call to action to ensure more balanced growth and a better and sustainable future for the planet and humankind. Three SDGs (#8, #12 and #14), which focus on sustainable and inclusive economic growth, responsible production and consumption and promote a sustainable use of the oceans, seas and their resources, respectively, have been singled out by the United Nation World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) as being of particular relevance for the tourism industry. However, none of the initiatives reported on by the UNWTO’s “Tourism for SDGs” platform focusses on the Polar Regions, scholarly research exploring SDGs in relation to polar tourism is in its infancy with academic publications thus far centring on sustainable development in the Arctic more broadly (e.g., Nilsson and Larsen, Reference Nilsson and Larsen2020) or the transfer of knowledge around environmental governance from the Arctic and Antarctic to the third pole, and in particular the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (Shijin et al., Reference Shijin, Wenli and Qiaoxia2023). We acknowledge the importance of the SDGs in relation to tourism development globally and the opportunities to utilise the unexpected and dramatic pause to cruise tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to rethink and redesign cruise operations such that they are in better alignment with the SDGs (Eskafi et al., Reference Eskafi, Taneja and Ulfarsson2022). Polar tourism operators stand to gain from such contemplations although evidence that these have occurred is scarce, and it is beyond the scope of this article to explore these opportunities with the attention to detail they deserve (see, e.g., Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Cajiao, Roldan, Benayas, Herbert, Leung, Tejedo, Dinica and Portella Sampaio2022 for an Antarctic perspective).

In this brief review, we explore how ship-based tourism in the Polar Regions, in specific in the high Arctic and the Antarctic, has developed over the last few decades along with how our understanding of its impacts and governance has evolved over time. We examine to what extent tourism scholarship and governance have kept pace with tourism operations and consider what past and present developments might mean for the future(s) of tourism in the coastal regions of the polar north and south. The paper is based on a review of the peer-reviewed literature accessible through Web of Science, Scopus and the authors’ personal databases. In addition, we compiled a database of published work specifically on tourism impacts that have been either studied or observed in the Polar Regions.

Development and status of polar ship-based tourism

Aside from the brief hiatus during the COVID-19 pandemic, both the Arctic and the Antarctic regions are receiving growing numbers of cruise tourists over the past decade, but growth rates vary between regions and localities. Visitation across destinations in the Arctic differs dramatically by country, with visitation data indicating that, before the COVID-19 pandemic, every year approximately a million cruise passengers visited Alaska, approximately 75,000 journeyed to Svalbard, approximately 25,000 visited Greenland and almost 5,000 went to the Canadian Arctic (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Johnston and Stewart2014; Lasserre and Têtu, Reference Lasserre and Têtu2015; Van Bets et al., Reference Van Bets, Lamers and van Tatenhove2017; Têtu et al., Reference Têtu, Dawson, Lasserre, Lasserre and Faury2019). Some emerging Arctic cruise regions have seen a rapid growth over the last decades (e.g., Greenland), while growth in other more mature Arctic tourism destinations has been fairly steady (e.g., Svalbard, Alaska). The number of Antarctic visitors in the pre-COVID (2018–2019) season was around 75,000, while tourist numbers are expected to rise to 108,000 in the first season without COVID-19 restrictions (International Association on Antarctica Tour Operators [IAATO], 2022).

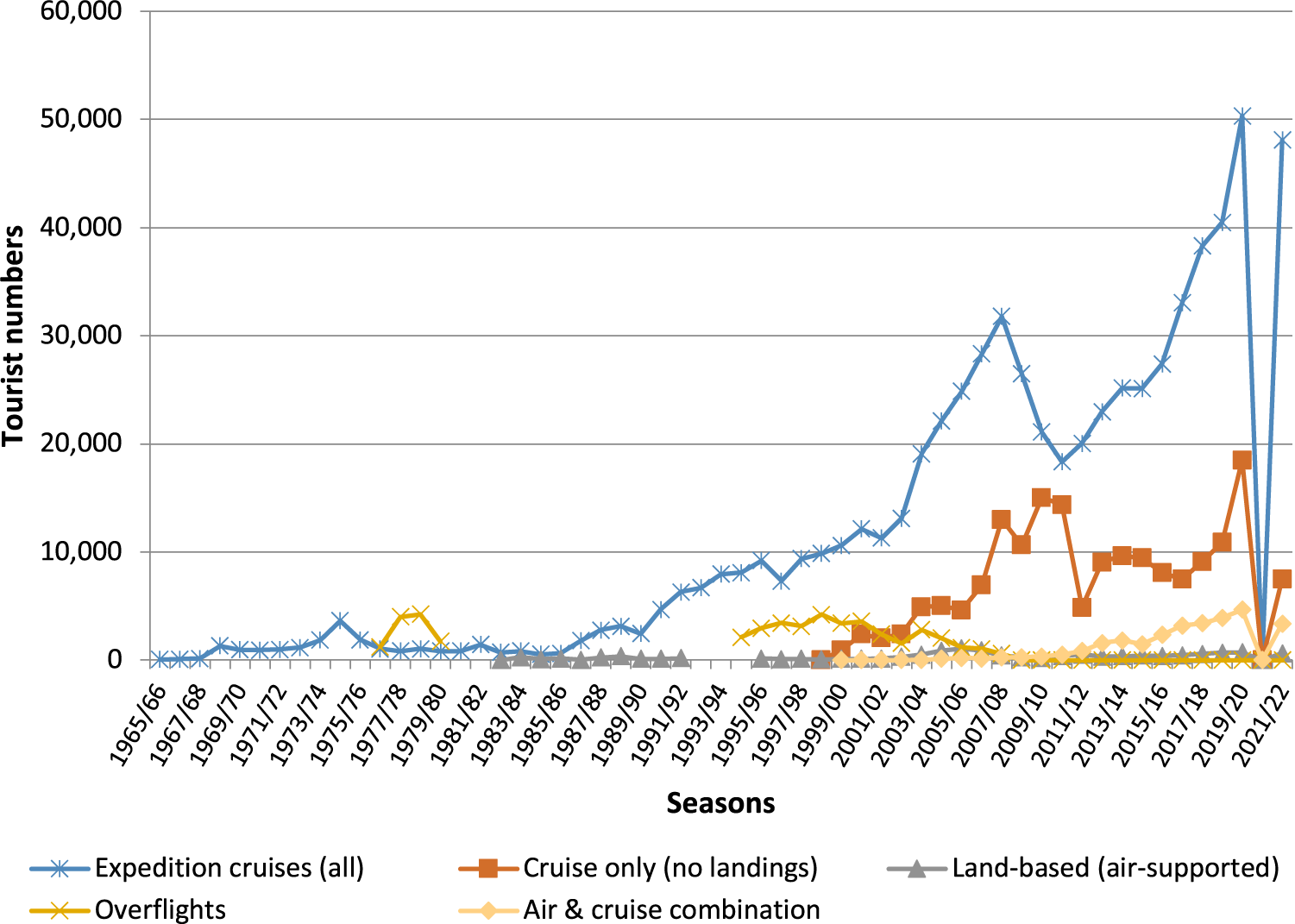

Global shocks, such as the 2007–2008 global financial crisis (GFC) and the recent COVID-19 pandemic, starkly illustrate that polar tourism is not protected from the disruptions created by greater global forces (Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Saarinen and HallIn Press). Energy intensity of cruise trips combined with long-haul air travel (Amelung and Lamers, Reference Amelung and Lamers2007; Farreny et al., Reference Farreny, Oliver-Solà, Lamers, Amelung, Gabarrell, Rieradevall, Boada and Benayas2011), the high price of polar cruise itineraries, the vulnerability of human activities in remote ice-strewn polar waters, as well as the health risks associated with life on board cruise ships, make polar cruise tourism especially susceptible to pressures on global demand via, for example, pandemics, conflict, and economic recession. This is particularly visible in the fluctuations seen in the numbers of Antarctic tourists over the past few decades (Figure 1) and is one of the reasons why our focus in this article is on polar ship-based tourism generally, and cruise tourism more specifically.

Figure 1. The Modern Era of Antarctic Tourism: Number of Antarctic tourists by main mode of transport since 1965. Sources: IAATO statistics (www.iaato.org) and a range of publications for data prior to 1991 (Enzenbacher, Reference Enzenbacher1992, Reference Enzenbacher1994, Reference Enzenbacher2002; Headland, Reference Headland1992, Reference Headland1994, 2005; Reich, Reference Reich1980) [N.B. The 2021/22 data denote forecasted instead of reported numbers.]

In most regions (except Alaska), ship-based tourism is dominated by expedition-cruise vessels, with many of the same vessels operating both in the Arctic and Antarctic (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Liggett, Lamers, Ljubicic, Dawson, Thoman, Haavisto and Carrasco2019). Expedition cruising utilises small vessels (between 20 and 500 passengers), offers shore landings and exploration using rubber boats, extensive interpretation, on-site wilderness experiences, and endeavours to minimise environmental and social impact while ensuring human safety. During expedition cruises, passengers engage in an increasing variety of coastal and marine activities, including hiking, camping, climbing, skiing, kayaking, scuba diving, and citizen science projects (Lamers and Gelter, Reference Lamers and Gelter2012; Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Hoke, Lamers, Liggett, Ljubicic, Mills, Stewart and Thoman2017a,Reference Dawson, Johnston and Stewartb). As the name suggests, one of the hallmark characteristics of expedition cruise tourism is the flexibility operators build into their itineraries to allow for swift changes in activities undertaken or locations visited that consider dynamic weather and sea-ice conditions. Overall, polar cruise tourism is diversifying, with visitation undertaken in increasingly diverse forms, from trips on large cruise ships with thousands of passengers to small vessel yacht excursions (Johnston et al., Reference Johnston, Dawson, De Souza and Stewart2017).

Marine and coastal tourism in the Polar Regions is not exclusively about cruising or yachting, but also includes visits to coastal natural and cultural sites (e.g., World Heritage sites, North Cape) and towns (e.g., Tromsø), and various forms of adventure tourism activities. Particularly in the relatively more urbanised parts of the European Arctic, such activities can be undertaken by car, rail or air. In the Antarctic, around the time of the new millennium, we have also seen the emergence of air-cruise operations, whereby visitors fly to the South Shetland Islands and then join a cruise ship for onward travel to the Antarctic Peninsula. These developments underscore the dynamic and changing nature of mobilities in the polar tourism sector (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Liggett, Lamers, Ljubicic, Dawson, Thoman, Haavisto and Carrasco2019).

Cruise tourism in the Polar Regions is characterised by a strong seasonality. It is typically concentrated in the respective summer months due to unfavourable weather and sea-ice conditions as well as limited opportunities to view wildlife in colder seasons. However, in both Polar Regions, dramatic changes in sea-ice extent and thickness and, in particular, diminishing sea-ice cover in the Arctic and around the Antarctic Peninsula region (see, e.g., Stroeve et al., Reference Stroeve, Barrett, Serreze and Schweiger2014; Meredith et al., Reference Meredith, Stammerjohn, Venables, Ducklow, Martinson, Iannuzzi, Leng, van Wessem, Reijmer and Barrand2017) allow expedition-cruise and yacht operators to move into even higher latitudes and to extend the lengths of their operating season from earlier in the spring into later in the summer (Bender et al., Reference Bender, Crosbie and Lynch2016; Stocker et al., Reference Stocker, Renner and Knol-Kauffman2020).

Polar cruise tourism increasingly mobilises passengers from around the globe. For example, about a decade ago tourism source markets for Arctic and Antarctic expedition cruises were dominated by North American, European and Australasian passengers, but more recently we have witnessed rapid growth in markets from emerging economies, such as China and India. In fact, before the pandemic, China rose to become the second largest source market for Antarctic tourists, after the United States (IAATO, 2022). It has been argued that such changes in visitor profiles might lead to different expectations, aspirations and behaviours by tourists and operators, which represent a cause for concern about a shift in visitors’ cultural and ethical perspectives and associated management implications (Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Bauer and Deng2019).

Polar tourism governance

Marine and coastal tourism in the Polar Regions is governed through complex networks of both state and non-state entities at various levels. In the Arctic, states exercise control over their sovereign territories, which include their territorial waters up to 12 nautical miles from their coastlines and which therefore include those coastal waters and ports that are important arrival and departure points for Arctic cruise tourism activities. Increased vessel activities in the Arctic, by cruise tourism operators and other users, result in growing controversies and debates about who should reap the benefits from, and assume the responsibilities for governance over, waters, such as the Northwest Passage, that will become more and more important for ship traffic (Boylan, Reference Boylan2021).

Each of the eight Arctic states has its own ambitions and subsequent policy frameworks for regulating and managing cruise tourism and ensuring the safety of passengers as well as the sustained well-being of coastal ecosystems and communities. These policies are aligned and complemented with standards and stipulations from various intergovernmental organisations and agreements, such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), and the Arctic Council. Alongside UNCLOS which provides and overarching legal framework for operating in the world’s oceans (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Mcgrath-Horn, Riley, Rotar, Singh, Tobin, Urban, Young, Burgess, Foulkes, Jones, Merighi, Murray and Whitacre2017), the most significant international maritime conventions for polar cruise tourism are as follows:

-

• the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) with its focus on safety requirements (Anderson, Reference Anderson2012);

-

• the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) MARPOL 73/78 (Vidas, Reference Vidas2000), with its focus on environmental protection (Palma et al., Reference Palma, Varnajot, Dalen, Basaran, Brunette, Bystrowska, Korablina, Nowicki and Ronge2019); and

-

• the IMO’s Polar Code, with its focus on technical requirements for ships and crew sailing in polar waters (Dalaklis et al., Reference Dalaklis, Baxevani and Siousiouras2018; Deggim, Reference Deggim, Hildebrand, Brigham and Johansson2018; Karahalil et al., Reference Karahalil, Ozsoy and Oktar2020; Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Scott and VanderZwaag2020).

The IMO’s ban of heavy fuel oil (HFO) in the Antarctic, in effect since 2011, is particularly relevant, from an environmental but also an economic perspective, as it requires cruise ships to operate solely on more costly light marine fuel oil while in Antarctic waters (Jabour, Reference Jabour, Tin, Liggett, Maher and Lamers2014; Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Scott and VanderZwaag2020). The seventh session of the IMO’s Pollution Prevention and Response Sub-Committee’s meeting in February 2020 has decided to implement a similar policy for the Arctic and phase out the use of HFOs there from July 2024 onwards (Bai and Chircop, Reference Bai, Chircop, Chircop, Goerlandt, Aporta and Pelot2020; Comer et al., Reference Comer, Osipova, Georgeff and Mao2020).

In an Arctic context, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is also noteworthy as it provides a framework for states to develop national legislation regarding the trade and transport of wildlife, which is relevant in relation to sports and hunting tourism in the North (Chanteloup, Reference Chanteloup2013; Larm et al., Reference Larm, Elmhagen, Granquist, Brundin and Angerbjörn2018).

Aside from the above multilateral agreements and intergovernmental organisations, regional regimes also contribute to, or (especially in the Antarctic) shape, the regulation and management of polar tourism. In the northern Polar Region, the Arctic Council represents such a regional regime. The Arctic Council offers an intergovernmental forum for Arctic states to exchange and coordinate policy-relevant knowledge, scientific assessments and agenda setting for Arctic issues in the international arena (Barry et al., Reference Barry, Daviðsdóttir, Einarsson and Young2020). The Council has worked extensively on marine and maritime issues, as evidenced, for example, by its flagship Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment reports (Arctic Council, 2009), with direct relevance for cruise-ship operators and decision-makers (Gunnarsson, Reference Gunnarsson2021). More specifically, under the auspices of the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment Working Group (PAME), best-practice voluntary guidelines for marine tourism were established in 2015 to strengthen existing mandatory requirements and various voluntary policies/guidance to support sustainable marine tourism in the Arctic (Fries, Reference Fries2016).

Governmental regulation of Antarctic cruise tourism is organised differently because of the absence of exclusive territorial sovereignty in the Antarctic (Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Saarinen and HallIn Press). In addition to the applicability of international maritime regulation, such as via UNCLOS, responsibility for the regulation of human activities in the Antarctic is assumed by a collection of states that have decision-making rights in the Antarctic Treaty System, which is the principal governance arrangement for the area south of 60° S Lat.Footnote 1 and is formally dedicated to governing the Antarctic in the interest of humankind, prioritising the maintenance of peace and scientific cooperation in the region (see the 1959 Antarctic Treaty). Human activities in the Antarctic, including tourism operations, are addressed in the most recent addition to the Antarctic Treaty System, the Protocol on Environmental Protection (hereafter the Protocol), which entered into force in 1998. Of greatest relevance to tour operators are the Protocol’s waste management requirements and the need for environmental impact assessments preceding tourism activities in the Antarctic Treaty area for anyone residing in a signatory state to the Protocol. The limited applicability of any international agreement, including those under the umbrella of the Antarctic Treaty System, or UNCLOS and MARPOL, which we referred to earlier, to signatory states and anyone under their jurisdiction, remains problematic and is, for example, accentuated by the limited reach of jurisdiction in the high seas to flag states, with the majority of polar cruise vessels registered in states that are not Antarctic Treaty signatories (Swanson et al., Reference Swanson, Liggett and Roldan2015; Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Scott and VanderZwaag2020). However, the former is but one of the concerns that scholars have raised regarding the Protocol (Kriwoken and Rootes, Reference Kriwoken and Rootes2000; Hemmings and Roura, Reference Hemmings and Roura2003; Brooks et al., Reference Brooks, Jabour and Bergstrom2018; Hughes et al., Reference Hughes, Constable, Frenot, López-Martínez, McIvor, Njåstad, Terauds, Liggett, Roldan, Wilmotte and Xavier2018; Carey, Reference Carey2020).

Indeed, ensuring the consistent implementation of Protocol stipulations across different national jurisdictions (Dodds et al., Reference Dodds, Hemmings and Roberts2017; Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Scott and VanderZwaag2020) remains a challenge, much like expanding the suite of binding regulatory mechanisms to respond to emerging issues, for example, in relation to diversification of tourism activities in the Antarctic, the expansion of operations to a greater number of sites, or the growth in numbers in general due to a seeming lack of urgency by the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Parties to do so and the mechanics of consensus-based decision making at Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings (Snyder, Reference Snyder, Snyder and Stonehouse2007; Huber, Reference Huber, Berkman, Lang, Walton and Young2011; Verbitsky, Reference Verbitsky2013; Liggett and Stewart, Reference Liggett, Stewart, Scott and VanderZwaag2020; Molenaar, Reference Molenaar2021).

The perception that Antarctic tourism does not urgently require top-down regulatory action is, at least in part, thought to relate to the fact that the Antarctic cruise tourism sector itself is playing an important role in self-regulating (Haase et al., Reference Haase, Lamers and Amelung2009). In 1991, the IAATO was founded, and in 2003, Arctic tour operators followed suit and founded the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO). Both, IAATO and AECO, have since developed a suite of binding and non-binding mechanisms that are aligned with these organisations’ overarching goals of ensuring sustainable, environmentally responsible and safe tourism operations in the Arctic and Antarctic (Splettstoesser, Reference Splettstoesser2000; Landau and Splettstoesser, Reference Landau and Splettstoesser2008; Haase et al., Reference Haase, Lamers and Amelung2009; Van Bets et al., Reference Van Bets, Lamers and van Tatenhove2017).

Polar tourism impacts

The growth and diversification of polar tourism is also cause for increasing concerns about various impacts tourism can have on polar environments and communities. Impact is a neutral term that can have positive connotations (e.g., economic benefits reaped or and improved knowledge through citizen science) or negative ones where it relates to environmental pressures leading to, for example, habitat destruction and pollution (Erize, Reference Erize1987; Hall, Reference Hall1992; Hall and Johnston, Reference Hall, Johnston, Hall and Johnston1995; Mason, Reference Mason and Mason2017; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Espiner, Liggett and Taylor2017). Tourism impacts across the two Polar Regions vary in terms of their nature, permanence, intensity, and scale.

Presently, there is no consensus on conceptual and methodological approaches to define and assess transitory and cumulative impacts in Antarctica (Roura and Hemmings, Reference Roura and Hemmings2011; (Bastmeijer and Gilbert, Reference Bastmeijer and Gilbert2019). For the purposes of this article, we distinguish between impacts by their permanence, that is, their duration of existence. Transitory impacts refer to those that emerge and dissipate in a short time period; they usually disappear with the removal of the impacting factor (New Zealand, 1997 WP35 ATCM XXI). In contrast, some impacts are long-lasting and can interact with other elements in space and time, producing cumulative, or synergistic, effects (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1999; Roura and Hemmings, Reference Roura and Hemmings2011).

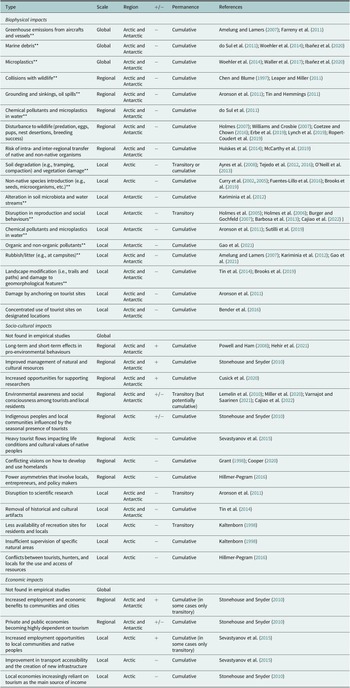

Table 1 summarises results of our analysis of the peer-reviewed scholarly literature on polar tourism impacts and is organised by three sustainability pillars (biophysical, socio-cultural, economic) and spatial scales (global, regional and local), showing positive or negative impacts that are common to either both Polar Regions or are exclusively applicable to one region. We also indicate if an impact is considered transitory or cumulative.

Table 1. Studied or observed impacts associated with tourism in the Polar Regions by type, scale, region, character (i.e., whether an impact has positive (+) or negative (−) consequences) and permanence

N.B.: Tourism is not considered the main cause of impacts denoted by**.

At the global level, the negative effects of polar tourism, such as carbon emissions (Amelung and Lamers, Reference Amelung and Lamers2007; Farreny et al., Reference Farreny, Oliver-Solà, Lamers, Amelung, Gabarrell, Rieradevall, Boada and Benayas2011), marine pollutants and microplastics (Kukučka et al., Reference Kukučka, Lammel, Dvorská, Klánová, Möller and and Fries2010; Ibañez et al., Reference Ibañez, Morales, Torres, Borghello, Haidr and Montalti2020) mainly relate to transport-related emissions or pollutants and are thus not unique to marine or coastal tourism. Farreny et al. (Reference Farreny, Oliver-Solà, Lamers, Amelung, Gabarrell, Rieradevall, Boada and Benayas2011), for example, estimated the total CO2 contributions of Antarctic travel to be 5.44 tons of CO2 per passenger while trying to address what resembles a considerable lack of data on the global impacts of polar tourism in terms of energy consumption and CO2 emissions. Collisions with wildlife and the death of injured individual animals as well as the introduction of microplastics or non-organic pollutants into the polar environment through tourism have also been examined (do Sul et al., Reference do Sul, Barnes, Costa, Convey, Costa and Campos2011) (Table 1), but the actual contributions made by tourism activities in relation to their impacts are yet to be sufficiently ascribed.

At the regional level, the presence of human communities in the Arctic has meant that more research attention was placed on social and economic dimensions of polar tourism, resulting in a larger body of research analysing the positive and negative effects arising from tourism in relation to socio-cultural dimensions. Although it is debatable where exactly the line between transitory and longer-term impacts is to be drawn, cumulative positive impacts can be associated with economic benefits and the well-being of local and Indigenous populations (Stonehouse and Crosbie, Reference Stonehouse, Crosbie, Snyder and Stonehouse2009; Stonehouse and Snyder, Reference Stonehouse and Snyder2010; Sevastyanov et al., Reference Sevastyanov, Korostelev, Gavrilov and Karpova2015). However, researchers recognise conflicting visions among tourism stakeholders (Indigenous communities vs. tourism industry) when it comes to weighing the economic benefits obtained from tourism operations against those originating from other economic activities (Hillmer-Pegram, Reference Hillmer-Pegram2016). Conflicts regarding the use and availability of resources as well as the potential erosion of Indigenous cultures (cosmovision, mythology) and communities have also been identified as lasting negative consequences of tourism (Grant, Reference Grant1998; Kaltenborn, Reference Kaltenborn1998; Kruse, Reference Kruse2016; Cooper, Reference Cooper2020).

At the local scale, scholars have emphasised the negative environmental effects of tourism, especially in Antarctica. Several studies have examined wildlife behaviour in response to human activities at visitor sites, with almost all of them concluding that the presence of humans within a certain radius of, for example, bird colonies, has a negative, but apparently transitory, impact on wildlife (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Giese and Kriwoken2005; Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Giese and Kriwoken2008; Coetzee and Chown, Reference Coetzee and Chown2016; Coetzee et al., Reference Coetzee, Convey and Chown2017; Cajiao et al., Reference Cajiao, Leung, Larson, Tejedo and Benayas2022). Negative cumulative environmental impacts include the potential introduction of invasive species and trampling of microscopic flora and fauna in areas of concentrated tourist activities and along designated visitation routes. Observed impacts include soil erosion, the development of muddy areas and vegetation loss, particularly in moss communities in the Antarctic Peninsula (Tejedo et al., Reference Tejedo, Pertierra, Benayas, Convey, Justel and Quesada2012; Bender et al., Reference Bender, Crosbie and Lynch2016; McCarthy et al., Reference McCarthy, Peck, Hughes and Aldridge2019). Although recovery appears to be possible after several years, ecological transitions and other lasting consequences of visitation at fragile sites need to be further evaluated (Cajiao et al., Reference Cajiao, Albertos, Tejedo, Muñoz-Puelles, Garilleti, Lara, Sancho, Tirira, Simón-Baile, Reck, Olave and Benayas2020). In the Arctic, trail-associated landscape modification and rubbish or litter left at tourist attractions have been observed (Sevastyanov et al., Reference Sevastyanov, Korostelev, Gavrilov and Karpova2015). Researchers also reported increasing visual and noise pollution due to ship traffic along the coasts and fjords and the operation of aircraft (Kaltenborn, Reference Kaltenborn1998).

While some potential impacts can simply be anticipated, more complex impacts may result from the interactions of multiple tourism-related stressors, in addition to pressures originating from other human activities elsewhere. For example, the decrease in ice cover due to climate change could facilitate vessel access to other remote and presently inaccessible sites (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Howell, Draper, Yackel and Tivy2007; Lemelin et al., Reference Lemelin, Dawson, Stewart, Maher and Lück2010), which might, in turn, not only have overall additive negative effects but might also trigger the spatial expansion of potential impacts by, for instance, the introduction of alien species and pathogens to the region (Huiskes et al., Reference Huiskes, Gremmen, Bergstrom, Frenot, Hughes, Imura, Kiefer, Lebouvier, Lee, Tsujimoto, Ware, van de Vijver and Chown2014).

Regardless of the region, scale, and nature of impacts, disentangling impacts of tourism from other human activities, such as subsistence activities, mining, fishing, transportation, and science (including infrastructure and operations of NAPs in the Antarctic, and the Arctic Council States in the Arctic) remains a challenge (Arctic Council, 2022; Tejedo et al., Reference Tejedo, Benayas, Cajiao, Leung, De Filippo and Liggett2022). In addition, we note that some of the regional impacts of polar marine tourism are concentrated in places outside the Arctic and Antarctic, and particularly in locations that serve as polar gateways. For instance, in the case of Antarctic tourism’s five Antarctic gateway cities – from east to west: Christchurch (New Zealand), Hobart (Tasmania, Australia), Capetown (South Africa), Ushuaia (Argentina) and Punta Arenas (Chile) – are the main thoroughfares en route to the Antarctic and consequently may reap considerable economic benefits from Antarctic tourism. However, gateway cities may also be disproportionately impacted, for example, by having to dispose of waste originating from an Antarctic cruise in landfills in the next port-of-call, that is, a gateway city (see, e.g., Huddart and Stott, Reference Huddart and Stott2020).

As spatial or temporal scales of human activities in the Polar Regions increase, more factors are added to the mix and may exacerbate or mask tourism-induced effects. Consequently, attributions of impacts to tourism exclusively tend to become more difficult at broader spatial and temporal scales (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Li, Gao, Hou, Jin, Ye and Na2021; Tejedo et al., Reference Tejedo, Benayas, Cajiao, Leung, De Filippo and Liggett2022).

While some actual impacts of polar tourism have been identified by researchers (Table 1), many potential impacts are yet to be explored. For example, a potential global consequence of polar tourism may be an increased environmental awareness and greater adoption of pro-environmental behaviours by tourists who visited the Polar Regions and obtained a sense of their fragility (Hehir et al., Reference Hehir, Stewart, Maher and Ribeiro2021). These potential positive impacts have been readily adopted by the tourism sector under the concept of ambassadorship (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Liggett, Leane, Nielsen, Bailey, Brasier and Haward2019). However, a deeper understanding is needed regarding whether and how experiences and memories acquired during a polar journey might trigger positive long-term behavioural and attitudinal changes (Powell et al., Reference Powell, Brownlee, Kellert and and Ham2012; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hallo, Dvorak, Fefer, Peterson and Brownlee2020; Cajiao et al., Reference Cajiao, Leung, Larson, Tejedo and Benayas2022).

From a socio-cultural perspective, more empirical evidence is needed to evaluate the long-term influence of tourism in cultural and social aspects among local and Indigenous communities. Proposals such as for the creation of “cultural centres” as spaces that foster positive interactions between tourists and locals are meaningful topics for further research (Cooper, Reference Cooper2020).

Concluding observations: Where to in the future?

As we have explored in this article, ship-based tourism in the Polar Regions has been growing and diversifying, a development that has been captured in a maturing body of scholarly research, the breadth and depth of which has also expanded, and that has become more organised (Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Espiner, Liggett and Taylor2017). To increase transparency and collaboration among polar tourism researchers, they have self-organised into international research groups, including the International Polar Tourism Research Network (IPTRN), the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research’s Antarctic Tourism Action Group (Ant-TAG) (see https://www.scar.org/science/ant-tag/home/), and the Academic Consortium for the 21st Century’s (AC21) Antarctic Tourism Research Project. Key polar tourism research needs that have been communicated by scholars, as outlined in this article, include gaps in knowledge around the complex and interconnected nature of tourism impacts on integrated socio-ecological systems, along with the need for a better understanding of how we can effectively monitor and manage negative impacts while maximising potential benefits arising from tourism operations. Before the latter is possible, we need greater awareness of suitable indicators of tourism impacts that can be assessed and monitored. Here, any monitoring ought to be carefully designed to not create unjustifiably large adverse impacts in its own right. In addition, it is worth exploring how tourists themselves might be able to meaningfully contribute as agents of positive change. These emerging research themes have now also been recognised as worthy of investigation by funders, such as the Dutch Research Council (NWO) which awarded research funding of over 4 million Euros to four projects in 2022 addressing these research themes over the next 5 years (NWO, 2022).

Despite of the maturing body of polar ship-based tourism scholarship and more attention being paid to this work by policy-makers and funders alike, important questions about the future(s) of tourism to, and in, the Polar Regions and how tourism operators are to be regulated and managed remain. The remoteness of the Polar Regions, their important role in the earth’s climate system, and the rapid and intensifying changes we can observe in these regions as a direct consequence of the climate crisis, represent some of the reasons for why regulators, managers, tour operators and the tourists themselves (should) care about the Arctic and Antarctic. At the same time, they are what makes polar tourism governance a challenge. With international travel recovering from the shock of far-reaching travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, which essentially put polar tourism on hold, it is timely to ask whether any lessons have been learned from how the pandemic affected international travel and especially polar tourism operations? Arabadzhyan et al. (Reference Arabadzhyan, Figini, García, González, Lam-González and León2021), noting the disruptive nature of disease outbreaks, ask whether recent experiences during the pandemic might result in longer-lasting changes in the behaviours and decisions made by tourists. For instance, they wonder whether a greater number of tourists might choose to spend their holidays closer to where they live, or whether more environmentally responsible travellers might alter their behaviours at destinations in response to a discernible recovery of some of the ecosystems which received very few visitors during the pandemic (Arabadzhyan et al., Reference Arabadzhyan, Figini, García, González, Lam-González and León2021). The latter point prompts us to consider what role environmental stewardship might play in the context of polar tourism and whether, ambassadorship can actually occur without a tourist having an in-situ tourism experience in the Arctic or Antarctic.

Additional questions remain, for example, should “degrowth” (see Saville, Reference Saville2022) be proposed, with focus on value added and time spent wisely in the Polar Regions, rather than unfettered growth and diversification? However, a degrowth strategy is hugely contentious as it might make an already exclusive market segment even more exclusive, which raises important justice issues especially as access to the Global Commons, including the High Seas and the Antarctic, are concerned. In addition, due to the remoteness of the Polar Regions and the already substantial carbon footprint of visiting the Arctic and Antarctic, degrowth might not yield a substantial decrease in the actual environmental footprint of polar tourism. We need to ask, now more than ever before, whether polar tourism is, and can ever be, truly sustainable? How do we balance visitation with the needs of local communities or wildlife, and what would be the implications for polar tourism governance and management?

Our fascination with the ‘otherness’ of the Polar Regions, which forms one of their key attractions for visitors, might also serve humankind in the desire to understand and protect these icy worlds and their coasts and oceans. The aforementioned questions highlight that, although we have developed a better understanding of the characteristics and governance of polar tourism through a maturing body of scholarship, a range of compelling and pertinent unanswered questions remain for present and future tourism scholars to ponder.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/cft.2023.10.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the polar tourism research communities – in particular our colleagues involved in the International Polar Tourism Research Network (IPTRN) and the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research’s Antarctic Tourism Action Group (Ant-TAG) – for many insightful conversations over the years, which informed and shaped our own work.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. However, we wish to acknowledge the Academic Consortium for the 21st Century’s (AC21) Antarctic Tourism Research Project as this project stimulated collaboration on the topic of Antarctic tourism among three of the co-authors (D.L., D.C. and Y-F.L.).

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

Dear Jess Jones and Laeti Beck,

It is our pleasure to submit an invited review article on polar tourism to Coastal Futures.

Please note that we uploaded a table as supplementary material as we could not see an option for uploading tables.

In addition, and very importantly, when you set me up as a contributing author you misspelled my name. Please correct it to "Daniela Liggett" (as per our email exchanges and my email address).

Thank you,

Daniela