2.1 Introduction

Scandinavian countries are often held up as liberal frontrunners when it comes to human rights. Historically, this also held true for the otherwise politically thorny issues of asylum and immigration. Norway, for example, has significantly helped advance protection for internally displaced persons (IDPs) around the world. Denmark was the first country to sign and ratify the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1983 Aliens Act used to be described as the “world’s most liberal asylum legislation.”Footnote 1 And while many other European countries have continuously applied a minimalist interpretation of EU asylum law, for long Sweden championed both a more liberal policy and discourse (Stern Reference Stern2014; Fratzke Reference Fratzke2017). Both domestically and as part of foreign policy, concern for refugee and IDP rights has thus been a significant component of the “Scandinavian Humanitarian Brand” that the editors to this volume outline.

Today, however, this picture has arguably changed significantly. All three countries remain top donors to international refugee protection.Footnote 2 Yet, at the level of domestic asylum and immigration policy each of these Scandinavian countries have introduced a host of more restrictive measures in response to the “European asylum crisis” beginning in 2015. While many of these restrictive measures build upon and expand earlier restrictions (Gammeltoft-Hansen Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen, Fischer and Mouritzen2017), Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen and Hathaway2015 can nonetheless be seen as a significant turning point in terms of both intensifying restrictions and changing the internal policy dynamics in this area across the Scandinavian countries. Several of the Danish measures have made international headlines and prompted international responses. When Norway introduced a broad range of asylum and immigration restrictions in November 2015, one of the government parties, Fremskrittspartiet, made a particular point of stressing that this would make Norway “the most restrictive country in Europe” in national and international media.Footnote 3 That same month, a clearly emotional deputy prime minister, Åsa Romson, announced that Sweden would now apply a minimum interpretation of EU standards with the explicit ambition to push asylum seekers toward other countries instead.Footnote 4

The present chapter examines the various domestic policy measures adopted by Denmark, Norway, and Sweden in the field of asylum and immigration since 2015 and the dilemmas these raise for the traditional “Scandinavian Humanitarian Brand.” It argues, firstly, that the vast majority of these measures are designed around a common logic focused on making conditions for asylum seekers and refugees in the Scandinavian countries as unattractive as possible and thereby push asylum seekers toward other countries and regions. It is secondly argued that this kind of policymaking can be conceptualized as a unique form of negative nation branding and that, to achieve the deterrent effect of these policies, Scandinavian states are prompted to actively advertise new restrictions both in public discourse and through targeted campaigns toward migrants and refugees. The chapter finally discusses whether and to what extent negative nation branding in regard to asylum and migration have international spillover effects. How do the new and more restrictive domestic policies impact the Scandinavian Humanitarian Brand internationally? And to what extent can restrictive policies at the domestic levels coexist with Scandinavian aspirations to continue playing a leading role in regard to international refugee and IDP protection?

The following section first provides an overview of the three Scandinavian countries’ policy response to the 2015 European asylum crisis, arguing that in comparison to other countries the Scandinavian countries have relied on a particular set of indirect deterrence policies. Section two conceptualizes this form of indirect deterrence as a form of “negative nation branding.” Using Denmark as a case, section three proceeds to examine the relationship between domestic and international policymaking in this area. On this basis, the final section asks whether negative nation branding in regard to asylum and migration is a sustainable policy strategy for Scandinavian countries.

2.2 Scandinavian Responses to the 2015 European Asylum Crisis

There was a time where the Scandinavian region was generally seen as welcoming toward refugees and asylum seekers. Liberal asylum policies did not only fit well with these countries’ humanitarian self-image and broader support for human rights, but also reflected wider geopolitical and economic factors. As Chimni has pointed out, the Cold War produced a particular kind of humanitarian politics (Chimni Reference Chimni1998). Accordingly, for both sides receiving refugees became part of the ideological scoreboard and border jumpers, fleeing minorities and smuggled dissidents celebrated as allowing people to “vote with their feet.” Like many other Western states, the Scandinavian countries further operated guest worker schemes. Refugee integration was thus seen as a doable challenge, partly coextensive with existing social-economic programs.

From the 1970s, however, this welcoming attitude began to change. The 1973 oil crisis abruptly ended previously welcoming labor immigration schemes and created fears that asylum procedures might be abused by “welfare refugees” (Gibney and Hansen Reference Gibney and Hansen2003). The proxy wars of the 1980s further created large-scale displacement across several regions in the Global South. At the same time, globalization has made both knowledge of faraway destinations and transcontinental transportation more readily available. Taken together, this meant that Scandinavian and European countries were faced with new and different groups of refugees. Following the end of the Cold War, receiving refugees finally no longer served an ideological agenda. The way was thus paved for a new policy paradigm.

In response, Western states introduced a distinctly bifurcated form of humanitarianism when it came to refugees. With the post-Cold War emphasis on human rights, both international refugee assistance and the institution of asylum managed to survive and as a result of progressive human rights jurisprudence in some cases even expand eligibility to new classes of protection-seekers – e.g. persons fleeing gender-related persecution or widespread violence (Gammeltoft-Hansen Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen2019). Meanwhile, however, access to apply for asylum was being systematically curtailed. Legal measures were introduced to exclude refugees from the “procedural door” through the use of notions such as “safe countries” and “manifestly unfounded applications” (Vedsted-Hansen Reference Vedsted-Hansen, Nicholson and Twomey1999). Other measures aimed at physically preventing refugees from accessing the territory of the asylum state. In the 1990s the United States began interdicting refugees in international waters, returning them with no assessment of claims for political asylum – a form of extraterritorial migration control soon adopted by Australia and Europe (Ghezelbash Reference Ghezelbash2018). Through the introduction of carrier sanctions, private airline companies around the world were similarly forced to reject boarding to thousands of asylum seekers, who are unlikely to obtain a visa (Gammeltoft-Hansen Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen2011). The last two decades have finally seen international cooperation on border control becomes embedded in a host of different foreign policy arrangements, including transnational crime, development assistance, trade privileges, labor immigration quotas, and visa facilitation (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Hathaway Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen and Hathaway2015; Gammeltoft-Hansen and Vedsted-Hansen Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen and Vedsted Hansen2016).

The policy response by the Scandinavian countries to the events in 2015 may be seen as part of this wider “deterrence paradigm” (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Feith Tan Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen, Fischer and Mouritzen2017). More specifically, the policy measures introduced in each of the three Scandinavian countries followed a two-prong approach. On the one hand, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden all reintroduced temporary border controls inside the Schengen area. Similar internal controls have been introduced by several other European countries, such as Austria, France, and Germany. While politically controversial, not least at the EU level, the temporary controls have been extended several times and at the time of writing remain in place for all three countries.Footnote 5

On the other hand, a range of measures were introduced limiting rights and benefits for arriving asylum seekers and refugees. In Denmark, a new tertiary protection status, “temporary protection status,” was introduced in 2015 for those fleeing general violence and armed conflict.Footnote 6 Under this provision, residence permits are initially granted for a period of one year only, ensuring that cases are regularly reviewed to assess continued protection needs. For other categories of refugees, the duration of initial residence permits has similarly been reduced from five years to two years (Convention refugees) and one year (protection status).Footnote 7 Access to family reunification for those granted “temporary protection status” has also been removed during the first three years of residence unless special considerations apply.Footnote 8 The grounds on which asylum seekers can be detained have been increased, and an option has been introduced to waive the ordinary, automatic right to habeas corpus for detained asylum seekers in cases of mass influx.Footnote 9 Social benefits for refugees have been cut by 50 percent, and child care support and pensions for refugees are now graduated based on the length of the applicant’s stay in Denmark.Footnote 10 Legislation has been adopted granting the police the authority to search and seize funds and assets from asylum seekers to cover costs related to accommodation and other benefits.Footnote 11 Fees have similarly been introduced in connection with applications for family reunification and permanent residence for refugees. The latter is further subject to new requirements with regard to language and employment, and the waiting period for permanent residence has been extended to six years.

A similar picture emerges in Sweden and Norway. In Sweden, refugees afforded subsidiary protection are now granted shorter residence permits of thirteen months, and family reunification is limited to exceptional cases. Also, a new maintenance requirement means that, to obtain family reunification, refugees must be able to provide adequate housing and economic support for family members. Almost simultaneously, Norway adopted its own restrictive measures, many directly mimicking similar provisions in Danish and the revised Swedish law in regard to family reunification, including requirements regarding age, association with Norway, economic support and the ability to refuse family reunification to persons afforded subsidiary protection. In the area of asylum, Norway goes even further than its two neighbors, having introduced an emergency measure to deny access to asylum seekers at the borders of other Scandinavian countries and a “safe third country” measure enabling the Norwegian authorities to deny asylum seekers entering Norway from neighboring Russia.Footnote 12

On closer inspection, however, the Scandinavian policy measures remain somewhat different from the general approach to deterrence involving the physical or legal exclusion from accessing asylum set out above. Contrary to common wisdom, reintroducing physical border controls do not prevent asylum claims. In some cases, it may even increase the number of claims as asylum seekers stopped hoping to transit onward to reach Sweden or other Nordic countries are instead forced to submit their claim in Denmark. As a policy measure, border controls may have a deterrence effect in other states, further down (or in this case geographically up) the migratory trajectory: The Danish border control may limit the number of asylum seekers in Sweden, the Swedish border controls in Finland and Norway and so forth. But from a strict asylum perspective, it is not necessarily in the immediate self-interest of states to reintroduce border controls within an area otherwise governed by free movement. In the Nordic context, one exception in this regards concerns the controls introduced by Sweden for passengers crossing the Øresund bridge from Denmark by train. Here, Sweden imposed carrier sanctions, meaning that private security companies would perform controls at the Danish side and reject onward passage to anyone without proper documentation. Asylum seekers traveling by car across the bridge would however still only be checked on the other side of the bridge and hence able to apply for asylum with the Swedish authorities.

Reviewing the host of other restrictions adopted in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, few if any measures similarly impact who when arriving have access to claim asylum. Except for the Norwegian introduction of a “safe third country” rule in regard to Russia and different emergency measures, which have so far not been implemented in practice, none of the new restrictions impact groups of persons eligible for asylum. Rather, the focus is on measures designed to discourage asylum claims or divert them to other countries by making the conditions for asylum seekers and recognized refugees less attractive.

This form of “indirect deterrence” has emerged in other European countries as well post-2015. Germany has replaced financial benefits for asylum seekers with coupons which they exchange for food and clothing,Footnote 13 and limited access to family reunification for persons afforded subsidiary protection.Footnote 14 In France, a combination of year-long processing times, bureaucratic hurdles, and a lack of access to work and social welfare during the asylum process has been proposed to serve as a deterrent for asylum seekers.Footnote 15 Austria introduced a cap of eighty asylum applications per day in 2016, Belgium a cap of 250 applications per day.Footnote 16 Greece and Italy have similarly been reported to block physical access to submitting asylum applications temporarily.Footnote 17

Yet, the geographic and legal position of the Nordics means that indirect deterrence is likely to be a particularly important strategy in these countries. First of all, the Scandinavian countries remain geographically removed from the direct pressure that several south and east European countries face from irregular immigration. These and other frontline countries, such as Australia and the United States, are more likely to focus on physical deterrence mechanisms. In addition, the legal architecture within the EU means that Scandinavian countries are at least partially insulated from the effects of secondary movement of asylum seekers due to the Dublin System.

On the other hand, as highly developed welfare states subject to the EU’s law of free movement within the Schengen area, the Scandinavian countries remain particularly vulnerable to secondary movements of asylum seekers within Europe. Here again, however, differences in legal regulation remain significant. Norway and Denmark retain more regulatory freedom in comparison with Sweden and Finland. While Norway may be part of Schengen it is not directly bound by EU asylum and immigration law – even if historically different Norwegian governments have attempted to align domestic legislation with the developing EU Acquis in this area. Although an EU member state, Denmark similarly retains legal opt-outs in the areas of justice and home affairs, which means that neither the EU asylum directives, nor the directive on family reunification applies to Denmark. Denmark has not been hesitant to apply this comparative advantage when it comes to adopting deterrence measures. Several of Denmark’s policies on asylum and family reunification would thus not have been possible if it had had to comply with EU law in this area (Adler-Nissen and Gammeltoft-Hansen Reference Adler-Nissen, Gammeltoft-Hansen, Hvidt and Mouritzen2010).

2.3 Scandinavian Asylum and Immigration Policy as “Negative Nation Branding”

What unites the different kinds of indirect deterrence policies set out above is their underlying logic. They work by making the country’s asylum system and protection conditions appear as unattractive as possible. If successful, a “beggar-thy-neighbor” effect is thereby achieved, pushing asylum seekers toward other countries. However, for policies of this nature to achieve their objective, it is essential that prospective asylum seekers know of an intended destination country’s restrictive approach before arriving or launching an asylum application there.

The Scandinavian policies to indirectly deter asylum seekers may in that respect be characterized as a peculiar form of national reputation management or “nation branding.” Nation branding has been defined as “the application of corporate marketing concepts and techniques to countries, in the interests of enhancing their reputation in international relations” (Kerr and Wiseman Reference Kerr and Wiseman2013: 354). It can involve the simple establishment of a visual identity, as in the 2013 “Brand Sweden,” which includes a set of graphics, colors, and fonts, which is used across different government websites.Footnote 18 Nation branding may further involve the export of cultural tropes, concepts, and policies somehow linked to their national identity (Anholt Reference Anholt1998; Browning Reference Browning2007; Dinnie Reference Dinnie2008). As the editors to this volume emphasize, at the international level nation branding may also manifest itself as a political culture shaping countries’ outlook and actions in regard to foreign policy. Humanitarian issues such as international development, human rights, peace-brokering, and climate adaption technologies are thus often associated with Scandinavian foreign policy. This includes international assistance to refugees and IDPs, in regard to which several Scandinavian countries remain frontrunners, as mentioned in the introduction.

As pointed out in more recent scholarship, nation branding may however also be linked to a “competitive identity” (Anholt Reference Anholt2011) and the concept of the “competition state” (Angell and Mordhorst Reference Angell and Mordhorst2015). In a global and open economy, market-based states compete to attract things like financial investments and consumption, and this by implication also extends to certain kinds of “wanted migration” benefiting the economy – in particular tourists, business-travelers, highly skilled labor migrants, and fee-paying international students (Castles and Miller Reference Castles and Miller2003).

In a policy paradigm where receiving refugees is no longer positively linked to ideological, political, or economic incentives, the asylum seeker emerges vice versa appears as something to avoid and actively deflect through similar market-based means. Underscoring this point, substantial efforts have been made to commercially disseminate specific deterrence policies or to brand countries as generally “unwelcoming” toward asylum seekers and refugees. Scandinavian countries have translated and tried to communicate pedagogically the impact of new restrictive measures in the languages of major groups of asylum seekers. Norway, for instance, has run Facebook campaigns to dissuade particular groups of asylum seekers.Footnote 19 Denmark made the decision to take out advertisements in newspapers in key countries of transit in the Middle East, warning prospective asylum seekers about its new and more restrictive policies.Footnote 20 The former minister of immigration in Denmark, Inger Støjberg, similarly installed a counter prominently on the front page of the ministry’s website, enumerating the ultimately more than 150 restrictive measures adopted since she came into office. Similar campaign initiatives have also been adopted by non-European countries. Notably, Australia, as part of its “No Way” campaign, has had 30 feet long banners installed in key transit airports throughout South East Asia and published e.g. YouTube videos and a graphic novel warning prospective asylum seekers that they will not be able to make Australia their home.Footnote 21

While such measures, as well as transnational networks, may be reasonably effective in disseminating the deterrence message, information and communication gaps are likely to persist. Interview studies show that, while asylum seekers may have an overall idea of different asylum states as more or less welcoming, few have more specific and in-depth knowledge of the conditions they are likely to face in them (Brekke Reference Brekke2004). In other cases, deliberate misinformation and “overselling” regarding certain asylum countries can be a strategy used by human smugglers with access to particular routes or who stand to make a larger profit by organizing longer routes.

Beyond concrete initiatives, states may thus also seek to brand themselves more generally as “hard-line” countries when it comes to asylum and immigration. Assuming imperfect information among asylum seekers, these more general branding efforts may potentially be much more important than any specific measure of deterrence. Denmark has long openly justified its more restrictive asylum policies with reference to its desire to avoid asylum seekers. When Norway introduced a broad package of deterrence measures, the immigration minister and government coalition partners made a particular point to argue that the new restrictions would make Norway “the most restrictive country in Europe” when it comes to asylum.Footnote 22

Last, but not the least, negative nation branding is often disseminated – either intentionally or unintentionally – through the shock effect or identity clashes that restrictive migration policies may create vis-à-vis pre-existing conceptions or branding among international audiences. The restrictive migration measures in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway have each made international headlines. Pictures of an openly emotional Swedish deputy prime minister went worldwide, exactly because its symbolic illustration of the clash with common perceptions of Swedish policies in this area.Footnote 23 In the case of the Scandinavian countries, the branding effect is thus also tied to the radical policy shifts that the new and more restrictive regimes represent vis-à-vis the Scandinavian countries’ historically liberal stances in regard to asylum and immigration, as well as the seeming clash between this policy area and wider attempts to brand Scandinavia as humanitarian, pro-human rights and inclusive societies. In a highly controversial essay, Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek thus refers to Scandinavian welfare states, specifically Norway, as an utopian trope and hence pull factor for refugees.Footnote 24

2.4 Negative Asylum Branding and the Two-Level Game

The potential clashes between migration policy and the Scandinavian countries’ nation brands more generally, further raise the question what impact, if any, negative asylum branding has in regard to Scandinavian countries’ foreign policy engagement on refugee and migration issues.

Compared to the shifts in domestic policy, most Nordic countries have maintained the traditionally strong commitment to refugee protection and assistance as part of their foreign policy and development engagement. While nine European states, as well as the United States, either voted against or abstained from voting for the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in December 2018, all Nordic countries ultimately ended up endorsing the new migration agreement.Footnote 25 Similarly, while then Danish prime minister, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, aired the possibility of renegotiating the 1951 Refugee Convention in December 2015, the idea seems to have been quickly abandoned. On par with all other Nordic countries, Denmark thus signed the September 2016 New York Declaration, which reaffirms the 1951 Refugee Convention as “the foundation of the international refugee protection regime” and actively encourages more states to ratify the convention.Footnote 26

On the one hand, this may be explained as (partial) brand “resilience.”Footnote 27 At the level of foreign policy, the Humanitarian Brand is sticky, creating a situation where strong multilateral engagements vis-à-vis refugee protection have managed to coexist despite the domestic reorientation toward more restrictive policies. Internally, the apparent mismatch between domestic and international branding is sustained by bureaucratically different cultures. Despite repeated attempts to link development with domestic migration and readmission priorities (Nyberg Sørensen et al. Reference Nyberg Sørensen, Plambech, Cuttitta, Herrera, Dalum Berg and Cheng2019), national development agencies still maintain a degree of independence and their budgets subject to legal protections. Externally, the Scandinavian Humanitarian Brand has been earned over decades. With financial commitments and civil society structures still intact, the domestic shift does not necessarily change the position of Scandinavian countries vis-à-vis their peers when it comes to international cooperation in regard to refugees, IDPs, and migration.

So far, the Scandinavian countries, in particular when compared to GDP, have thus remained top donors to UNHCR and other aid programs targeting refugees and internally displaced. Denmark even served as chair of UNHCR’s governing body, the Executive Committee, from 2015 to 2016. Denmark has further spearheaded important intergovernmental initiatives to promote refugee protection, such as the Solutions Alliance launched in 2014. Scandinavian countries further benefit from the fact that they are home to some of the largest refugee-assisting NGOs in Europe. Both the Norwegian Refugee Council and the Danish Refugee Council are internationally renowned, have grown to see multi-billion kroner annual turnovers, and are consistently high ranked when it comes to international reputation.Footnote 28

On the other hand, despite different cultural-political logics, the coexistence of domestic deterrence policies and international humanitarianism need not necessarily to be at odds. The current Danish Social Democratic government has thus repeatedly justified its restrictive policies with arguments that the expenses linked to domestic asylum processing and refugee protection may help many more in places closer to refugees’ countries of origin.Footnote 29 This kind of utilitarian, cost-benefit analysis has also been forwarded by other countries, e.g. Australia, as justification for its “No Way” campaign (Hall Reference Hall2008). Likewise, policymakers have repeatedly sought to reframe deterrence measures as a particular form of humanitarianism, intended to “save lives” by blocking dangerous migration routes and reducing the “pull factor” of generous asylum systems in the Global North (Little and Vaughan-Williams Reference Little and Vaughan-Williams2017). As scholars within refugee studies have long demonstrated, the conceptual ambiguity of humanitarianism has always made the concept prone to co-optation and exclusion (Harrell-Bond Reference Harrell-Bond1986; Every Reference Every2008).

Nonetheless, both the domestic backlashes against migrant and refugee rights as well as the specific negative asylum branding strategies pursued are likely to create certain spillover effects on the international standing and maneuverability of Scandinavian countries. As perhaps the most long-standing proponent of negative nation branding in regard to migration, the case of Denmark is illustrative of the difficulties in limiting negative branding to the intended audiences. Denmark has thus repeatedly made international headlines, both as a result of concrete policy measures and as the result of the political communication of its migration policy on e.g. social media. Perhaps most famously, a picture on Facebook of then immigration minister, Inger Støjberg, celebrating restriction number 50 with cake went viral and prompted strong responses from international organizations and media.Footnote 30 Since 2017, the picture has repeatedly resurfaced, serving as a visual nodal point through which international media contextualize Denmark’s restrictive stance on immigration.Footnote 31

In 2016, newspapers around the world likewise responded to Denmark’s so-called “jewelry law,” allowing police to search and confiscate valuables from asylum seekers to help pay for their accommodation.Footnote 32 The provision was one among several deterrence measures, many of which were much more serious in terms of the human rights issues involved. Yet, an emotive link was made by several commentators, comparing the Danish proposal to the confiscation of valuables from Jews during the Second World War. When the British daily, The Guardian, printed a cartoon featuring then prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen in a nazi uniform alongside other known Danish brands, including Lego and Carlsberg, the Danish People’s Party demanded an apology and asked for it to be withdrawn.Footnote 33 The press attention ultimately led the Danish government to nuance the initial proposal, setting a threshold of EUR 1,350 and underscoring that personal assets such as wedding rings would not be seized.

Branding conflicts are further likely to emerge in areas where domestic and foreign policy aspects of migration/refugee policy are intrinsically linked. As part of its restrictive suite of measures following 2015, Denmark introduced a complete halt to its long-standing refugee resettlement program, arguing that its capacity to receive more refugees had been completely filled by spontaneous arrivals.Footnote 34 Notably, the announcement came less than two weeks before the first-ever UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants, at which a key objective was to mobilize states to implement or expand existing refugee resettlement schemes.

More recently, the new Social Democratic government in Denmark has begun consultations with other European heads of state to explore the possibilities for more radically reforming EU asylum policy.Footnote 35 A particular challenge for Denmark in taking on a leading role in this regard, however, remains Denmark’s carefully guarded EU opt-out in regard to justice and home affairs. Consequently, Denmark would not itself be able to vote for reforms to the existing Dublin rules and would in principle stand outside any substantially new EU-wide initiatives adopted under the ordinary legislative procedure.

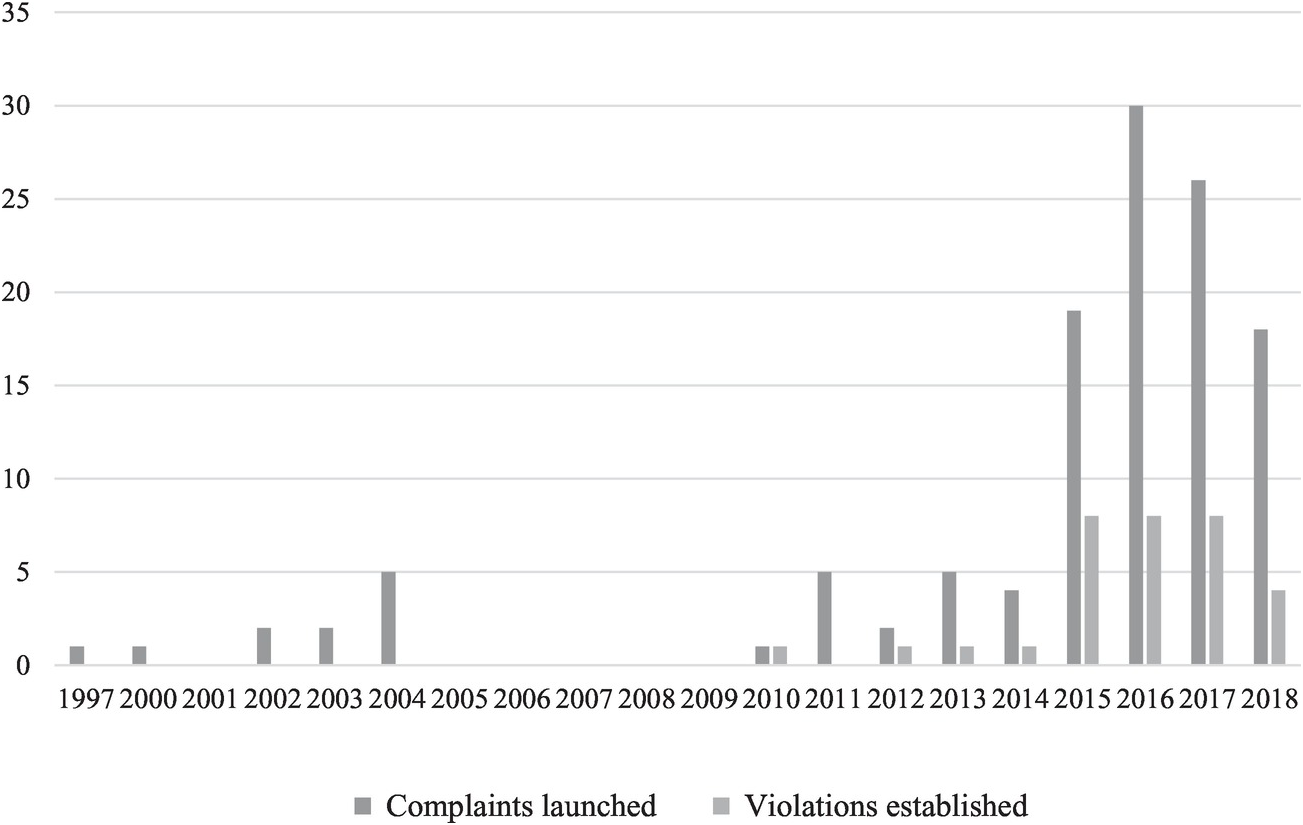

Vice versa, increasing international awareness of the Scandinavian countries’ more restrictive approaches may also have domestic implications. Asylum and immigration are issues closely circumscribed by international human rights law. During the past five years, Denmark has seen a marked increase in the number of complaints against decisions in asylum cases made by the Danish Refugee Appeals Board taken up by the UN human rights committees. The increase is particularly noticeable, since none of the restrictive measures Denmark has implemented in regard to asylum seekers the last decade in principle impact how the board works and the determination of who should be granted asylum.Footnote 36 This led members of Danish Refugee Appeals Board to speculate that the increasing finding of violations may be indirectly impacted by Denmark’s general reputation in this area, and a special consultation in Geneva was thus organized between the board and the committees in 2016 (Figure 2.1).Footnote 37

Figure 2.1 Individual complaints against the Danish Refugee Appeals Board at the UN human rights bodies.

Other parts of Denmark’s asylum and immigration policy have faced similar challenges, in particular when it comes to rules regarding family reunification. In 2016, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights found Denmark’s so-called “28 years rule” to constitute “indirect discrimination” in violation of Article 14 together with Article 8 of the Convention.Footnote 38 In doing so, the Grand Chamber of the court overturned a previous decision in the same from 2014 by the Court’s Second Section finding no violations of the convention. At the time of writing, another pending case concerning Denmark’s policy to defer access to family reunification for three years for certain categories of refugees has been deferred to the Grand Chamber.Footnote 39

Last, but not the least, the Danish experience suggests that over time negative branding may well come to impact the standing and maneuverability in the foreign policy realm. For a number of years, Danish diplomats working on issues related to migration and refugees were able to maintain a proactive foreign policy role in regard to refugee protection by arguing that the domestic policy restrictions were the result of a particular government coalition backed by the anti-immigration Danish People’s Party. Yet, this narrative became more difficult to sustain after further restrictions were introduced by the center-left government between 2011 and 2015 – including the above-mentioned three-year suspension to apply for family reunification. Likewise, the curtailment of the Danish resettlement program – albeit never very significant in terms of numbers – was seen as particularly symbolic by some other countries.Footnote 40 According to one Danish diplomat, Denmark had to work “unusually hard” and pledge additional funds to get invited to the special donors conference following the 2015 UN Summit for Refugees and Migrants.Footnote 41 In 2015, former Danish prime minister, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, was further rejected for the position as UN High Commissioner for Refugees. According to UN officials speaking on condition of anonymity, then UN General Secretary Ban-Ki Moon had decided against Thorning-Schmidt due to, among other things, her role in crafting some of Europe’s most restrictive immigration policies.Footnote 42

In conclusion, negative and positive nation brands in regard to migrants and refugees are not mutually exclusive. Despite the emphasis on deterrence and exclusion in terms of their domestic policies, Scandinavian countries have so far sought to maintain their humanitarian brand when it comes to international refugee and migration policy. Maintaining this split is not unproblematic, however, and spillovers are likely to happen between domestic and foreign policy brands. This can happen where international peer communities respond negatively to domestic policy orientations or when international media attention creates branding clashes. It is also likely to happen where domestic and international policy measures are directly linked, such as in the case of resettlement quotas, and where e.g. the Danish decision to suspend its refugee resettlement program in 2016 may be seen as free-riding, or even actively undermining the global agenda, by other states. In both cases, this has led diplomats having to work harder to maintain their countries’ international standing and it may lead to missed opportunities for international leadership that may or may not otherwise have been achievable.

2.5 Conclusion and Postscript: Is Negative Nation Branding a Sustainable Policy Strategy?

The present chapter has argued that the current wave of unilateral restrictive measures across the Scandinavian countries constitutes a distinct form of asylum and immigration policymaking. As opposed to other forms of migration control aimed at physically or legally blocking access to asylum, these policies restrict access to rights and benefits for asylum seekers and refugees already within the host state with a view to discouraging further arrivals. These policies are designed to make the prospective asylum country appear as unattractive as possible – and at the very least less attractive than neighboring states. Scandinavian states actively advertising restrictive measures toward prospective asylum seekers and their information networks may as such be considered a form negative nation branding.

This turn, from humanitarian frontrunners to self-proclaimed hardliners on asylum and immigration, stands in contrast to the continued engagement of Scandinavian states when it comes to promoting refugee protection and migrant rights as a matter of foreign and development policy. Yet, the nature of negative nation branding and the way these measures are disseminated (intentionally and unintentionally) through international media means that this bifurcation between domestic and international politics may be difficult to uphold over time.

As many other European states have begun to adopt similar measures in the post-2015 context, a final but important question is whether this kind of negative asylum branding is an effective and sustainable policy strategy. Previous research suggests that in at least some cases, consistent use and dissemination of negative nation branding strategies may indeed impact arrival numbers by prompting asylum seekers to move to other, often neighboring, countries (Brekke, Røed, and Schøne Reference Brekke, Røed and Schøne2016; Gammeltoft-Hansen Reference Gammeltoft-Hansen, Fischer and Mouritzen2017). In other cases, however, the deterrent effect remains limited or nonexistent (Havinga and Böcker Reference Havinga and Böcker1999; Holzer, Schneider, and Widmer Reference Holzer, Schneider and Widmer2000; Gilbert and Koser Reference Gilbert and Koser2006; Brekke and Five Aarset Reference Brekke and Five Aarset2009). Just as for other kinds of nation branding, the long-term effects of negative asylum branding thus remain questionable and difficult to measure (Anholt Reference Anholt2011).

Yet, the fact that policies of indirect deterrence may be effective in terms of lowering arrival numbers does not mean that states shouldn’t think twice before embarking on this path. In addition to the points set out in the previous section, most obviously the kinds of measures currently adopted place additional burdens on asylum seekers and refugees who have already arrived, raising questions in regard to both international law and political proportionality. Indirect deterrence policies are also more likely than other forms of migration management to negatively impact efforts to ensure the integration of refugees who are already in the country. This is particularly the case for policies involving deliberate delays in processing asylum claims, a lack of access to labor markets during the asylum phase, automatic national dispersal policies, and short-term residence permits, which have each been shown to impact negatively the later employment opportunities and economic performance of those who are subsequently afforded protection. Similarly, economic destitution and a lack of access to education and work experience may negatively impact decisions by rejected asylum seekers to return voluntarily and by refugees to agree to repatriation (World Bank 2016).

Indirect deterrence may further create negative externalities in respect of other issues. Both domestic and international law place certain limitations on the design of indirect deterrence with regard to nondiscrimination, making it difficult for governments to design policies specifically targeting certain groups or nationalities. The desire to maintain strict rules in respect of, for example, family reunification may thus inadvertently impact a country’s ability to attract wanted labor migration or necessitate restrictions on a wider group of national citizens – something that similarly risks impacting the wider nation brand of the country in question.

Last but not least, policies of indirect deterrence are by design premised on a “beggar-thy-neighbor” effect that fundamentally challenges their continued effectiveness in the long or even medium term. Once pursued, surrounding states are likely to respond with similar policies – either preemptively or once they experience the displacement effect – in ways that are likely to reduce, nullify, or even reverse the intended effect in the first country introducing them. More than anything, the return to this kind of competitive, instrumentalist, and zero-sum game policymaking across Europe is likely to fundamentally challenge Scandinavia’s Humanitarian Brand.