Introduction

Over the last several decades, developmentalists have increasingly concluded that theoretical frameworks of resilience (e.g., Denckla et al., Reference Denckla, Cicchetti, Kubzansky, Seedat, Teicher, Williams and Koenen2020; Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten, Cicchetti and Cicchetti2016; Masten, Reference Masten2021; Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021) provide a useful higher-order home for the study of the development of coping in children and youth (Compas et al., Reference Compas, Jaser, Bettis, Watson, Gruhn, Dunbar, Williams and Thigpen2017; Garmezy & Rutter, Reference Garmezy and Rutter1983; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2007, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2016, Reference Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2023; Tyrell & Masten, Reference Tyrell, Masten, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2023; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Skinner and Cicchetti2016). In fact, according to developmental systems approaches, the study of coping, which refers to the repertoire of actions individuals draw upon when they encounter challenges and problems in their daily lives, is located between the study of resilience above and the study of regulation below (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2007, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2016). On the one hand, coping incorporates processes of regulation: The tools children and youth use to manage their coping actions under conditions of stress call on underlying regulatory processes (Compas et al., Reference Compas, Connor, Saltzman, Thomsen, Wadsworth, Lewis and Ramsay1999; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Guthrie, Wolchik and Sandler1997; Skinner, Reference Skinner, Brandtstädter and Lerner1999). Based on dual process models of regulation, coping involves a balance between (1) individuals’ stress reactivity (i.e., their immediate emotional action tendencies or impulses) and (2) their regulatory capacities (i.e., the ability to modulate, guide, direct, or boost those impulses) under taxing circumstances. On the other hand, coping can contribute to higher-order processes of resilience: Coping actions (like problem-solving or seeking support) have the potential to buffer the development of children and youth from the otherwise deleterious effects of stress.

The study of resilience and of coping share many historical roots (for a review, see Tyrell & Masten, Reference Tyrell, Masten, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2023), but they diverge in scale. In work on what we call “big R” resilience, researchers focus on molar contexts of risk and adversity (like homelessness or maltreatment) as well as on longer-term developmental pathways and outcomes (like competence and psychopathology). Big R resilience is apparent when children and youth experience adversity but nevertheless show better-than-expected developmental pathways – toward fewer symptoms of psychopathology or greater competence. In contrast, coping refers to the ways individuals deal with and recover from immediate stressful encounters, and so – to mark this distinction – has been called “everyday coping” and “everyday resilience” (e.g., DiCorcia & Tronick, Reference DiCorcia and Tronick2011; Martin, Reference Martin2013; Skinner & Pitzer, Reference Skinner, Pitzer, Christenson, Reschly and Wylie2012; Wolchik & Sandler, Reference Wolchik and Sandler1997).

Complementarity of resilience and coping

As the social and biological sciences have increasingly been informed by developmental systems perspectives, however, the overlap between resilience and coping has become apparent. In recent years, both resilience (e.g., Cicchetti & Curtis, Reference Cicchetti and Curtis2007; Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti2016; Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten, Cicchetti and Cicchetti2016; Masten, Reference Masten2021) and coping (Compas et al., Reference Compas, Jaser, Bettis, Watson, Gruhn, Dunbar, Williams and Thigpen2017; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2016) have been conceptualized as integrated multi-level systems that reach from the genetic and biological levels up to the macro-system levels of society and globalization. From this perspective, resilience is defined as “the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully through multisystem processes to challenges that threaten system function, survival, or development” (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021, p. 521). Such definitions are designed to provide an integrative umbrella that allows the concept of resilience to be applied to a range of systems, not only within individuals, but also encompassing larger units, like the family, school, community, geographical area, natural ecology, and so on (Ungar, Reference Ungar2018).

In parallel, coping has also been described as the product of a complex multi-level developing system (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2007), operating on at least five levels: (1) neurophysiological; (2) psychological; (3) action; (4) social; and (5) societal. Definitions of coping as action regulation under stress anchor it to the interconnected processes of stress reactivity, action tendencies, and regulation that emerge on the level of action. These components specify the psychological processes that underlie coping; they involve the attentional, motivational, emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and meta-cognitive subsystems that together generate action tendencies and regulate them under stress. Underlying these, at the neurophysiological level, are the biological sub-systems used to detect and react to stress, to regulate stress reactivity, and to recover and learn from stressful transactions. Coping in turn is embedded in social processes that include local social interactions and relationships, as well as higher-order societal contexts that permeate the levels below. Hence, systems views of coping fit well within the umbrella of resilience, and coping researchers can rely on concepts of resilience to bridge to higher-order contexts of adversity (e.g., racism, poverty) and to frame the longer-term developmental pathways and outcomes that are at stake.

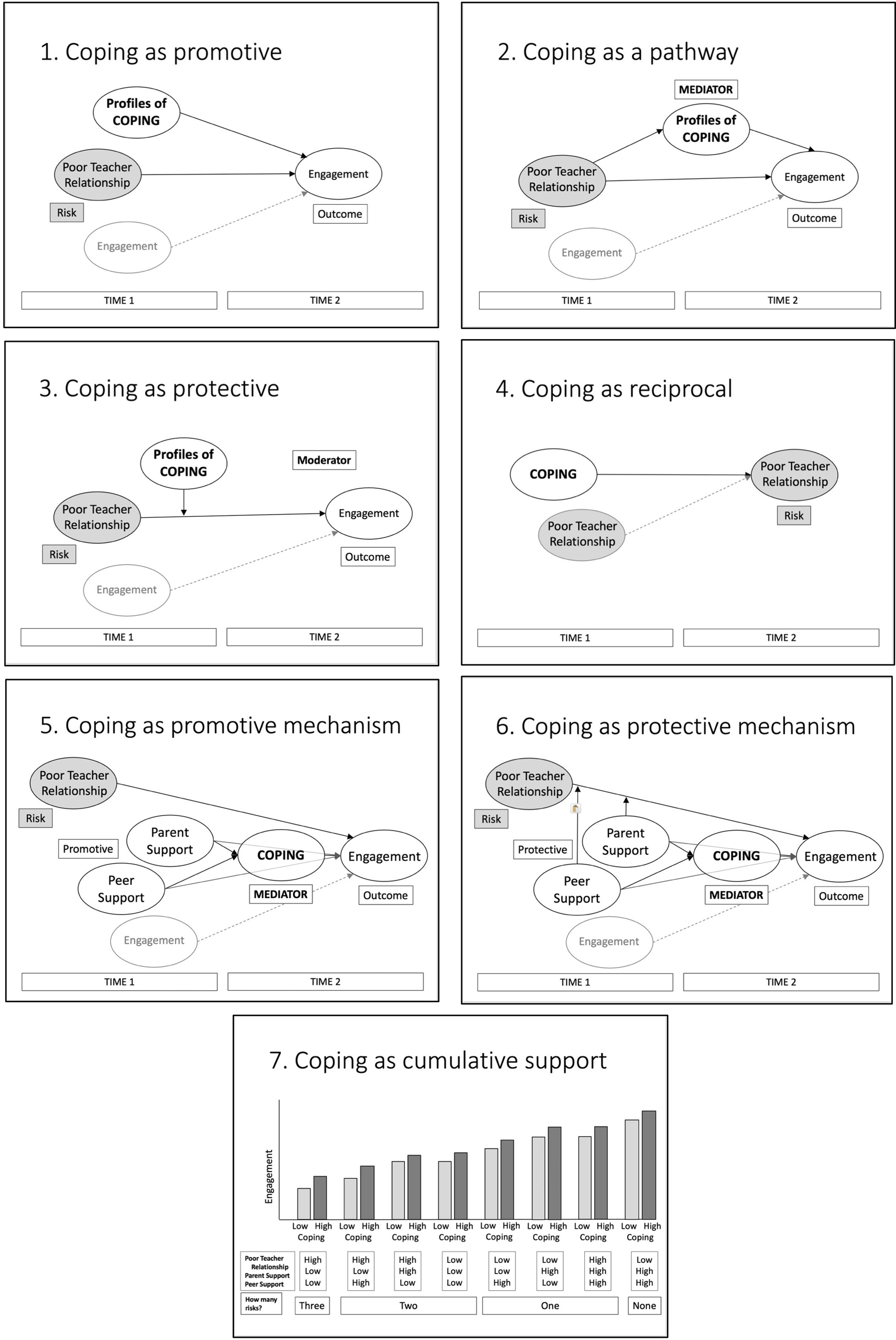

The goal of this paper is to build on previous work examining the complementarity between resilience and coping by proposing multiple ways in which coping can participate in processes of resilience, along with analytic strategies for examining these connections (for details, see Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Skinner and Cicchetti2016). Drawing from decades of research on the study of resilience (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021), we propose seven possibilities: Coping can serve as (1) a promotive factor, supporting healthy development at any level of risk; (2) a pathway through which risk contributes to development; (3) a protective factor that reduces the negative impact of adversity on development; (4) a reciprocal process generating risk when coping is poor; (5) a mechanism through which other promotive factors operate to support development; (6) a mechanism through which other protective factors operate; and (7) a participant with other supportive factors that can show cumulative or compensatory effects on development. We then examine these seven possibilities in the domain of academic coping during the developmental period of middle childhood and early adolescence. Our goal is to propose a more general set of strategies for exploring the role of coping in processes of resilience, with the understanding that only some of these pathways may be functioning in any given domain and age range.

The role of coping in resilience

The construct of coping highlights a specific set of ongoing person-context transactions inherent in big R resilience: Transactions in which children and youth face demands and problems in their daily lives. Hence, the study of coping focuses researchers’ attention on how risk and adversity generate day-to-day stressors in the lives of children and youth. As pictured at the bottom of Figure 1, transactional models of coping depict recursive cycles, in which individuals, when they encounter stressors, draw upon personal and interpersonal resources to appraise their meaning, and regulate their stress reactions via strategies of coping; these actions in turn contribute to short-term outcomes, which feed back to subsequent stressors, appraisals, resources, and coping actions. Cumulatively, these transactions form the arc of a coping episode, which ends when the stressor is resolved or the individual accepts the situation, gives up, or departs. These episodes accumulate over time, as shown in the slices of coping episodes pictured in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Multiple ways in which transactional episodes of coping can be involved in processes of resilience, including as (1) a promotive factor, supporting healthy development at all levels of risk; (2) a pathway through which risk contributes to development; (3) a protective factor that reduces the negative impact of risk on development; (4) a reciprocal process generating risk when coping is poor; (5) a mechanism through which other promotive factors operate to support development in the presence of risk; (6) a mechanism through which other protective factors operate; and (7) a participant with other supportive factors that can show cumulative or compensatory effects on development.

Hence, coping depicts ways that children and youth can fend off (or worsen) stress’s short-term effects, and potentially even use these encounters to develop greater stress resistance and better coping tools. Given what is known about the kinds of social relationships and supports that bolster adaptive coping in stressful situations, work on coping also suggests both individual and social factors that can reduce reactivity and strengthen regulation, thus enhancing the everyday coping responses of children and youth in the face of risk and adversity. From this perspective, coping influences everyday resilience and serves as a site of developmental potential for big R resilience. Because coping shapes how children and youth bounce back from daily stressors, these episodes can be opportunities for the development of regulatory capacities and coping efficacy, as long as stressors are manageable, personal and interpersonal resources are sufficient, and caregivers (and other social partners) help children channel setbacks and failures productively – by learning and growing from them. Such processes have sometimes been explicitly addressed in work on big R resilience, under the label of inoculation, steeling (Rutter, Reference Rutter1987), or challenge models, where “exposure to average levels of risk actually help[s] youths overcome subsequent exposure. The initial exposure to risk must be challenging enough to help youths develop the coping mechanisms to overcome its effects, but not so taxing that it overwhelms their efforts to cope” (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Stoddard, Eisman, Caldwell, Aiyer and Miller2013, p. 216).

Coping in the academic domain

The academic domain is one area where stress and coping repeatedly occur for almost all children and youth. Academic coping refers to the ways students deal with the (actual or anticipated) challenges, difficulties, and setbacks they encounter in their schoolwork, including impending exams, boring tasks, mistakes and failures, and not meeting their own (or others') standards of performance. Recent reviews of research on school-age children and youth have identified core families of academic coping, both adaptive and maladaptive; documented links between ways of coping and markers of motivational and academic functioning and success; and summarized the kinds of personal and interpersonal resources that foster effective and reduce unproductive coping (Skinner & Saxton, Reference Skinner and Saxton2019).

Although much of this research has focused on specific ways of coping, like problem-solving, support-seeking, or escape, it seems that coping profiles are the strongest predictors of academic competence and performance. This suggests that it is the repertoire of coping strategies students have available to them, more than any one coping response, that allows them to effectively manage academic stressors (Boekaerts, Reference Boekaerts1993), deploying for example, problem-solving as well as help-seeking and effort exertion to make progress on difficult academic tasks (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Lau and Chan2014; Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Skinner, Modecki, Webb, Gardner, Hawes and Rapee2018; Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck2021). Hence, in the current study, we focus on profiles of academic coping that reflect the availability of a repertoire of adaptive responses (including strategizing, help- and comfort-seeking, self-encouragement, and commitment) combined with low reliance on maladaptive ways of coping (including escape, helplessness, concealment, self-pity, rumination, and opposition; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Pitzer and Steele2013).

Research points to multiple pathways through which academic coping supports students’ educational performance and success. Some of the most important seem to be motivational. For example, multiple studies have shown that adaptive academic coping is a predictor of student engagement, tenacity, buoyancy, and reengagement, not only concurrently, but also across the school year, school transitions, and multiple years (Causey & Dubow, Reference Causey and Dubow1993; Martin, Reference Martin2013; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Pitzer and Steele2016). Adaptive ways of coping, like strategizing and seeking instrumental support, allow students to intentionally garner information about how to effectively tackle educational activities; and other strategies, like comfort-seeking and commitment, allow students to regulate their emotions and motivation, so they can invest energy in the hard work needed to learn and persist in demanding tasks. In contrast, studies indicate that one pathway through which maladaptive coping leads to poorer academic functioning and performance is by undercutting students’ engagement and evoking distress, disaffection, and desistance in the face of challenging schoolwork (Skinner & Saxton, Reference Skinner and Saxton2019). Hence, as a target developmental outcome for this study of academic coping, we examined academic engagement, defined as students’ enthusiastic, effortful, and focused participation in educational activities, whose opposite is disaffection, or passivity, disinterest, and disengagement from schoolwork. This view is consistent with larger discussions on motivation (e.g., Martin, Reference Martin2009; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Graham, Brule, Rickert and Kindermann2020), the role of engagement in resilience (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Nelson, Gillespie, Christenson and Reschly2022), and research on engagement itself, which documents it as a positive force in students’ learning and academic success as well as a protective factor that buffers students from educational risks like underperformance and drop out (Parker & Salmela-Aro, Reference Parker and Salmela-Aro2011; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, Reference Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro2013).

Academic coping in a resilience framework

At its most general, the study of resilience involves an examination of how children and youth can develop along healthy pathways despite facing risks and adversity that typically exert a downward pressure on competence and functioning (Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten, Cicchetti and Cicchetti2016; Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021). In the academic domain, research has demonstrated the risks imposed by poor relationships with teachers, defined here as relationships that, while within the normal range, nevertheless involve higher than average experiences of neglect or rejection, chaotic or undependable practices, and overcontrol or coercion. Reviews and meta-analyses have documented the extent to which poor teacher-student relationships can undermine students’ motivation, engagement, academic functioning, performance, and success (Gregory & Korth, Reference Gregory, Korth, Wentzel and Ramani2016; Martin & Collie, Reference Martin, Collie, Wentzel and Ramani2016; Pianta et al., Reference Pianta, Hamre, Allen, Christenson, Reschly and Wylie2012; Quin, Reference Quin2017; Roorda et al., Reference Roorda, Jak, Zee, Oort and Koomen2017; Tao et al., Reference Tao, Meng, Gao and Yang2022; Wentzel, Reference Wentzel, Wentzel and Miele2016; Wigfield et al., Reference Wigfield, Eccles, Fredricks, Simpkins, Roeser, Schiefele, Lamb and Lerner2015). Multiple theories, chief among them attachment theory and self-determination theory (e.g., Connell & Wellborn, Reference Connell, Wellborn, Gunnar and Sroufe1991; Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2017; Sabol & Pianta, Reference Sabol and Pianta2012), offer explanations for these pervasive effects: When children have poor relationships with teachers, their basic psychological needs (e.g., for relatedness or autonomy) are not met in the classroom. When needs are not met, students do not internalize the value of educational activities and become less interested and motivated to exert effort to do well in school. Hence, poor relationships with teachers can be considered a risk factor for the loss of engagement and the development of disaffection, desistence, and motivational vulnerability (Quin, Reference Quin2017; Roorda et al., Reference Roorda, Jak, Zee, Oort and Koomen2017 Wentzel, Reference Wentzel, Wentzel and Miele2016; Wigfield et al., Reference Wigfield, Eccles, Fredricks, Simpkins, Roeser, Schiefele, Lamb and Lerner2015; Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Chipuer, Hanisch, Creed and McGregor2006).

Building on such findings, a resilience framework poses the question: How do students sustain or regain their enthusiasm, engagement, and tenacity in academic work despite a poor relationship with the teacher? The empirical question centers on whether and how coping profiles play a role in these processes. To explore this question, we examined the academic coping of students from third to sixth grade – before, during, and after the transition to middle school. This developmental window represents an important time to support students’ engagement, because it, along with other markers of motivation, typically decline over this transition, putting students at a disadvantage during middle school and setting them up for further losses over the transition to high school (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Degol and Henry2019; Wigfield et al., Reference Wigfield, Eccles, Fredricks, Simpkins, Roeser, Schiefele, Lamb and Lerner2015). To understand more about whether coping plays a role in the short-term development of engagement, we drew on data that assessed students’ engagement at two timepoints (beginning and end of the same school year), so that we could examine whether coping predicts changes in engagement across the school year.

Seven ways that coping can be involved in processes of resilience

Building on larger discussions in the field (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021), we propose seven ways that coping may participate in processes of resilience (Figure 1 and Table 1; Zimmer-Gembeck & Skinner, Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Skinner and Cicchetti2016). The analytic strategies used to examine them can be illustrated with academic coping, the risk factor of a poor relationship with the teacher, and the developmental outcome of student engagement. The first possibility is that coping acts as a promotive factor, making a positive contribution to the healthy development of children and youth at all levels of risk. This would register as a unique positive effect of students’ initial academic coping profiles (at the beginning of the school year) on changes in engagement across the year, over and above the negative effects of a poor relationship with the teacher. A second possibility is that coping could act as a pathway through which risk factors exert their impact on development. In that case, coping profiles (at year’s end) would mediate the effects of a poor relationship with the teacher at the start of the year on changes in engagement across the school year. If mediation is found, this would suggest that one way in which poor relationships with teachers undermine engagement is by making it harder for students to cope productively when they encounter academic difficulties.

Table 1. Seven ways coping can participate in processes of resilience

A third possibility is that coping functions as a protective factor, whereby a positive coping profile buffers the negative effect of poor teacher-student relationships on engagement. In the academic domain, that would mean that the engagement of students who show high profiles of coping may be unaffected or less negatively affected by a poor relationship with the teacher compared to students with low profiles of coping. To examine this question, coping profiles (at the beginning of the year) would be tested to see whether they moderate the effects of poor teacher relationships at the beginning of the year on changes in student engagement over the school year. Promotive or protective effects suggest that bolstering academic coping may be one lever schools can use to help students sustain their engagement, even in the face of poor relationships with teachers.

The other ways that coping could be involved in processes of resilience are more complicated, reflecting the dynamic system in which both are embedded. A fourth possibility explores whether coping is part of a reciprocal loop with risk. Assuming feedforward effects, in which poor relationships with teachers interfere with the development of adaptive profiles of coping, this complementary pathway could be described as a feedback effect, in which coping profiles in turn predict changes in relationships with teachers over time. In stress and coping research, these processes have also been labeled as stress generation (e.g., Liu, Reference Liu2013), consistent with the idea that children and youth can act in ways that increase the objective stressors in their lives. For example, when children cope by giving up, this makes academic failure more likely, which brings with it additional stressors. Consistent with this possibility, a few studies have shown that children’s adaptive coping (e.g., help-seeking, problem-solving) can elicit more support from adults, just as stress-affected coping (e.g., escape, self-pity) can lead adults to respond less supportively (Seiffge-Krenke & Pakalniskiene, Reference Seiffge-Krenke and Pakalniskiene2011; Skinner & Edge, Reference Skinner, Edge and Crockett2002). Feedback effects can be tested by examining whether students’ coping (at the beginning of the year) predict changes in relationships with teachers across the school year. If both feedforward and feedback effects are found, this suggests the presence of vicious cycles, in which poor teacher relationships contribute to poorer coping which can in turn undermine relationships even further.

The last set of possibilities considers whether coping is involved in processes of resilience by participating with other factors in mitigating or compensating for the effects of risk. For example, coping could be a pathway through which other promotive or protective factors exert their positive effects on development. In terms of engagement, other potential protective and promotive factors in the face of poor teacher relationships can be suggested by developmental systems models designed to capture the complex social ecologies surrounding academic development (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Rickert, Vollet and Kindermann2022; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Degol and Henry2019). These models posit that factors from multiple microsystems, like school, family, and peers, converge to shape the development of students’ academic functioning, including their engagement. From this perspective, potential promotive factors would include supports provided by other important social partners from these microsystems, chief among them, parents and peers. Large bodies of research have shown that these two kinds of relationships both play important roles in students’ academic and motivational functioning in school (Barger et al., Reference Barger, Kim, Kuncel and Pomerantz2019; Grolnick, Reference Grolnick, Liu, Wang and Ryan2016; Kindermann, Reference Kindermann, Wentzel and Ramani2016; Lerner et al, Reference Lerner, Grolnick, Caruso and Levitt2021; Ryan & Shin, Reference Ryan, Shin, Bukowski, Laursen and Rubin2018; Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, Reference Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro2013; Wigfield et al., Reference Wigfield, Eccles, Fredricks, Simpkins, Roeser, Schiefele, Lamb and Lerner2015) and, in multiple studies, parent and peer supports have also been associated with more positive profiles of academic coping (Skinner & Saxton, Reference Skinner and Saxton2019).

Hence, a fifth possibility is that profiles of adaptive coping might be a pathway through which support from parents or peers exert their promotive effects; and a sixth would be as a mechanism of protective effects. Such models can be tested in two steps. Supports from teachers and peers would be tested individually to see whether each one acts as a (1) a promotive factor that makes unique contributions to changes in engagement over and above the effects of poor teacher relationships; or (2) a protective factor that buffers (i.e., reduces or eliminates) the negative effects of poor teacher relationships on changes in engagement. If so, then coping profiles would be tested as a mediator of the effects of parent and peer support on changes in engagement.

The seventh and final way we propose coping could be involved in processes of resilience could be as part of cumulative risk and support (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Li and Whipple2013; Masten & Cicchetti, Reference Masten, Cicchetti and Cicchetti2016; Rutter, Reference Rutter1979, Reference Rutter1981; Sameroff et al., Reference Sameroff, Seifer, Barocas, Zax and Greenspan1987). Social ecological frameworks argue that it is the combinations of risks and supports from multiple interpersonal partners that collectively shape developmental outcomes (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Rickert, Vollet and Kindermann2022). Cumulative effects could be tested in the academic domain by creating subgroups based on whether students are high or low (e.g., above or below the median) on the risk factor (a poor relationships with the teacher) and the two potential supports (i.e., parent support, peer support). Then subgroups could be created that show different patterns of cumulative risk and support, ranging, for example, from high risk (worse relationships with teachers combined with low parent and peer support) to no risk (better relationships with teachers combined with high parent and peer support). Then analyses could examine (1) cumulative effects (i.e., whether coping adds to the effects of other resilience factors, even in the presence of risk) by testing whether coping profiles (i.e., high vs. low) make a difference to student engagement for each subgroup; and (2) compensatory effects (i.e., whether coping fully counteracts the effects of risk) by testing whether differences among subgroups in their mean levels of engagement disappear when analyses hold constant or control for coping profiles.

The current study

The primary goal of this study was to highlight multiple ways that coping could be involved in processes of resilience, by illustrating these possibilities in relation to academic coping and the effects of a poor relationship with the teacher on students’ engagement measured twice across one school year among children in grades 3–6. Findings should be of interest to researchers, practitioners, and interventionists wishing to support students’ engagement across these important years (Fredricks et al., Reference Fredricks, Reschly and Christenson2019). At the same time, independent of specific findings, the larger set of strategies may be of interest to those wishing to explore the role of coping in processes of resilience that protect and promote development in other domains and during other age periods.

Method

Participants and procedure

For the current study, data were drawn from the third year of a larger 4-year longitudinal study of students’ academic coping, motivation, and engagement that consisted of 1,020 third through sixth graders representing an entire school district in a rural-suburban town in upstate New York. Participants were roughly evenly split between girls and boys, 95% white, and predominantly lower-middle to middle class as measured by parents’ education and occupation.

Surveys were administered to students at the beginning (October; T1) and end (May; T2) of a single school year in class without their teachers present as part of regular school assessments by two trained interviewers. 87.8% of students participated at both time points. Completion of questionnaires occurred over three 40-minute sessions with one interviewer reading survey questions aloud while the other was available to answer students’ questions. This study received human research protection approval through the Portland State University Institutional Review Board (application #00032).

Measures

Variables included in the present study were student self-report and utilized a 1–4 Likert-type scale consisting of “not at all true,” “not very true,” “sort of true,” and “very true.” For each measure except poor relationships with teachers, items were roughly evenly split between positive and negative, with negatively valanced items reversed scored.

Academic coping profile

Student coping was assessed using a multidimensional measure of coping in the academic domain comprised of 11 five-item subscales tapping five adaptive (strategizing, help-seeking, comfort-seeking, self-encouragement, commitment) and six maladaptive (escape, confusion, helplessness, concealment, rumination, opposition) ways children can deal with challenges and setbacks in their schoolwork (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Pitzer and Steele2013). Items included one of four stems, “When I run into a problem on an important test…”, “When something bad happens to me in school (like not doing well on a test or not being able to answer an important questions)…”, “When I have trouble with a subject in school…”, and “When I have difficulty learning something…”. Item responses to these stems tapped different ways of coping (e.g., problem-solving: “I try to figure out how to do better next time;” concealment: “I try to hide it.”). Multiple confirmatory structural analyses, conducted in heterogenous samples, have supported the multidimensional structure of this measure (Gonçalves et al., Reference Gonçalves, Lemos and Canário2019; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Pitzer and Steele2013).

Many strategies have been used to combine different coping subscales into aggregate scores (e.g., relative, ratio, proportion, allocation, and configuration scoring), some of which use ipsative procedures to account for the amount of total coping each student shows (both adaptive and maladaptive), based on the idea that higher objective stress and greater stress reactivity produce more coping of every kind. In this study, an ipsative method was used in which items from the five adaptive subscales were averaged with reverse-coded items from the six maladaptive subscales to create an aggregate academic coping profile score, in which higher values indicated a balance favoring adaptive over maladaptive ways of coping. These scores showed high inter-item reliabilities at both T1 and T2 (αs = .89 and .92, respectively).

A poor relationship with the teacher

Students’ relationships with their teachers were assessed by averaging items from three subscales tapping neglectful/rejecting, chaotic, and coercive interactions with teachers (Skinner & Belmont, Reference Skinner and Belmont1993). Eight items tapped students’ perceptions of their interactions with teachers as rejecting or neglectful (i.e., characterized by dislike, inaccessibility, and lack of understanding; e.g., “My teacher doesn't seem to enjoy having me in her class”). Fourteen items tapped students’ experiences of their interactions with teachers as chaotic (i.e., unhelpful, inconsistent in discipline and expectations, and unaware of students’ progress and learning in the classroom; e.g., “My teacher keeps changing the rules in class”). Eleven items assessed coercive interactions, tapping students’ perceptions of teachers as controlling, not respecting their perspectives, and assigning work that lacked personal relevance (e.g., “My teacher makes me do everything his/her way”). These aggregate scores, in which a higher value indicated a poorer relationship with the teacher, showed high inter-item reliabilities at T1 and T2 (αs = .95 and .96, respectively).

Student engagement

Academic engagement was assessed by averaging items designed to tap students’ enthusiastic, effortful, and focused participation in learning activities in the classroom (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Kindermann and Furrer2009). Ten items measured engaged and disaffected behaviors such as students’ effort, focus, and hard work (e.g., “I work hard when we discuss something new in class” and “When I’m in class I just try to look busy,” reverse coded) and 15 items tapped emotional engagement and disaffection, such as enjoyment, interest, and enthusiasm (e.g., “When I’m doing my work in class I feel involved” and “When my teacher first explains new material I feel bored,” reverse coded). The aggregate measure, in which higher scores indicated more engagement, showed high inter-item reliability at T1 and T2 (αs = .89 and .92, respectively).

Parent support

Parental support was assessed using eight items tapping students’ sense of relatedness to their mothers and fathers, which were averaged to create an aggregate score (Furrer & Skinner, Reference Furrer and Skinner2003). Four items tapped children’s emotional security and connection to each parent (e.g., "When I’m with my mother, I feel accepted” and “When I’m with my father, I feel unimportant,” reverse coded). This aggregate measure, in which higher scores indicated more parent support, showed acceptable inter-item reliability at T1 and T2 (αs = .75 and .85, respectively).

Peer support

Peer support was measured using eight items assessing students’ relatedness to their classmates and friends, which were averaged to create an aggregate score (Furrer & Skinner, Reference Furrer and Skinner2003). Items tapped students’ feelings of belonging and acceptance from their friends and classmates (e.g., “When I’m with my friends I feel like I belong” and “When I’m with my classmates I feel left out,” reverse coded). This aggregate measure, in which higher scores indicated more peer support, showed high inter-item reliability at T1 and T2 (αs = .80 and .86, respectively).

Analysis plan

Analyses were designed to test the seven ways academic coping could be involved in processes of motivational resilience in the face of the risk posed by a poor relationship with the teacher. Six of them were examined using variable-centered analyses (i.e., multiple regression models). The seventh used a pattern-centered approach (i.e., creation and comparison of subgroups of students). A final path analysis was used to test a model that combined all previous variable-centered analyses.

The seven analytic strategies followed directly from the seven ways coping could participate in processes of resilience, as listed in Table 1. First, to examine whether coping acted as a promotive factor, analyses tested whether students’ coping profiles at T1 uniquely predicted increases in their engagement across the school year, over and above the negative effects of a poor relationship with the teacher at T1. Second, to examine whether coping acted as a pathway, analyses tested whether the effects of a poor teacher relationship at T1 on declines in students’ engagement from T1 to T2 were mediated by their coping profiles at T2. Third, to examine whether coping acted as a protective factor, analyses tested whether students’ coping profiles at T1 moderated the effects of a poor teacher relationship at T1 on changes in students’ engagement across the school year. Fourth, to examine whether coping exerted a feedback effect, analyses tested whether students’ coping profiles at T1 predicted changes in poor teacher relationships from T1 to T2.

Fifth, to examine whether coping acted as a mechanism of promotion, analyses first tested whether parent and peer support at T1 made unique contributions to changes in student engagement over and above the effects of poor teacher relationships (promotive effects), and then whether coping profiles at T2 mediated those effects. Sixth, to examine whether coping acted as mechanism of protection, analyses first tested whether initial parent and peer support moderated the effects of a poor teacher relationship at T1 on changes in student engagement from T1 to T2 (protective effects), and then whether coping profiles at T2 mediated those effects.

Seventh, the possibility that coping is part of cumulative risk and support was examined using person-centered analyses in four steps. Because analyses were for illustrative purposes only, a very simple a priori strategy was intentionally used to create subgroups (see von Eye et al., Reference von Eye, Bergman, Hsieh, R., Overton and Molenaar2015, for more possibilities). First, students were divided into eight subgroups that differed on their initial combinations of cumulative risk (high vs. low poor teacher relationships, based on a median split) and parent and peer support (high versus low, based on median splits) at T1. Second, using analysis of variance, mean level differences among subgroups in student engagement were tested. Third, using analysis of variance, the possibility of coping as a cumulative support was examined for each subgroup by determining whether students’ mean levels of engagement differed as a function of whether they were high versus low on coping (based on a median split). Fourth, to examine the possibility that coping showed compensatory effects, an analysis of covariance was used to testing whether mean level differences among subgroups disappeared when coping was held constant.

In a final analysis, the first six variable-centered analyses were tested simultaneously in a multivariate longitudinal path model (using the lavaan package in R; Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012) to determine if it had a good fit to the data. This model was considered a representation of the multiple ways that academic coping was (and was not) involved in mitigating the risk created by the experience of poor teacher relationships and in promoting the resilience of students’ engagement over the school year. To examine fit, alternative fit indices including the comparative fit index (CFI), tucker lewis index (TLI), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used with a general threshold of greater than .90 for acceptable and .95 for good fit for CFI and TLI, and less than .08 for acceptable and .05 for good fit for RMSEA and SRMR (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999).

Results

Missing data

Missingness on individual items ranged from 10.5% to 27%, with the most missing on a single teacher relationship item in spring (“I can't depend on my teacher for important things”). Little’s MCAR test (2012; χ 2(130092) = 135,779.08, p < .001) indicated that data could not be interpreted as missing completely at random as defined by Rubin (MCAR; 1976). Therefore, data were examined for significant relationships between missingness on one item with their value on another using t-tests. While a portion of these tests were significant, effect sizes for these tests were small, suggesting that they were influenced by the large sample size (N = 1,020), and therefore provided some tentative evidence that data may be missing at random (MAR). To maintain all participants in all analyses, missing data were imputed using the EM-ML algorithm (Schafer, Reference Schafer1997) within the mclust package in R (Scrucca et al., Reference Scrucca, Fop, Murphy and Raftery2016).

Descriptive findings

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables are presented in Table 2. On average, students reported coping profiles that favored adaptive strategies along with high supports from parents and peers. Similarly, children’s reports of a poor relationship with the teacher were relatively low (averaging 2.06 across T1 and T2, on a scale whose midpoint was 2.5). As is typical of research in the area (Wigfield et al., Reference Wigfield, Eccles, Fredricks, Simpkins, Roeser, Schiefele, Lamb and Lerner2015), students generally reported high levels of engagement, which decreased significantly from T1 to T2, t(1019) = 5.30, p < .001. As expected, a poor relationship with the teacher was significantly negatively correlated with all other variables, which in turn were significantly positively correlated with each other. Correlations were medium to large in magnitude (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988), with the highest correlations between the risk factor of a poor teacher relationship and children’s coping profiles (r = −.70, averaged across T1 and T2), as well as between students’ engagement and their coping profiles (average r = .67). Cross-time stability of student engagement was also high (r = .71), indicating that it might be difficult to predict change over time.

Table 2. Summary of descriptive statistics, inter-item scale reliabilities, and correlations

Note. N = 1020 third through sixth graders. All scale scores could range from 1 (“not at all true”) to 4 (“very true”). T1 correlations are below the diagonal, T2 correlations are above the diagonal, and correlations on the diagonal are cross-time stabilities. All correlations were significant p < .001.

Academic coping as part of processes of resilience

Findings are presented in three steps: (1) results of variable-centered analyses examining six ways coping could be involved in processes of resilience; (2) results of person-centered analyses examining cumulative and compensatory effects of coping; and (3) results of models simultaneously testing multiple ways coping could participate in processes of resilience.

Academic coping as a promotive factor

To examine whether coping was promotive (Figure 2, panel 1, Coping as promotive), that is, whether coping uniquely predicted changes in engagement over and above the negative effects of a poor relationship with the teacher, a multiple regression was calculated in which poor teacher relationships, students’ coping profiles, and levels of engagement at T1 were used as predictors of engagement at T2. Results indicated that having a poorer relationship with the teacher uniquely predicted greater decreases in engagement from T1 to T2 (β = −.11, p < .001) while higher coping profiles uniquely predicted greater increases (β = .17, p < .001), even when controlling for the autoregressive path from T1 to T2 engagement (β = .55, p < .001). Thus, these findings suggest that coping may exert promotive effects, in that it positively predicts changes in engagement over and above the effects of poor relationships with teachers.

Figure 2. Depiction of multiple ways coping can function as part of processes of resilience in the academic domain, including as (1) a promotive factor, predicting the short-term development of student engagement over and above the effects of the risk factor of a poor teacher relationship; (2) a pathway mediating the effects of a poor teacher relationship on changes in engagement; (3) a protective factor that moderates the negative effects of a poor teacher relationship on the development of engagement; (4) a reciprocal process in which poor coping predicts increases in poor teacher relationships; (5) a mechanism that mediates the promotive effects of parent and peer support on changes in engagement over and above the effects of a poor teacher relationship; (6) a mechanism that mediates the protective effects of parent and peer support; and (7) a participant with risk and support factors that can show cumulative or compensatory effects on student engagement.

Academic coping as a mediator of risk

Children’s academic coping was also investigated as a potential mechanism through which a poor relationship with the teacher shapes changes in students’ engagement (see Figure 2, panel 2, Coping as a pathway). Direct and indirect effects were tested using regression models and bootstrapping to determine the significance of the indirect effect of teacher relationships at T1 on engagement at T2 via child coping profiles at T2 (adjusting for engagement at T1). We first established the presence of a significant direct effect of teacher relationships at T1 with engagement at T2 (β = −.19, p < .001), adjusting for the effect of engagement at T1 (β = .55, p < .001). Next, the path from teacher relationships at T1 to coping profiles at T2 was tested, revealing a significant negative association (β = −.58, p < .001). Finally, when coping at T2 was added as a predictor, having a poor teacher relationship was no longer a significant predictor of engagement at T2 (β = .02, p = .572), while coping profiles at T2 still predicted a greater increase in engagement from T1 to T2 (β = .49, p < .001). Lastly, a significant indirect effect from poor teacher relationships to engagement through coping was found using bootstrap estimation with 1000 samples within the lavaan package in R (Rosseel, Reference Rosseel2012; β = −.29, p < .001). All together, these results indicated that children’s coping profiles fully mediated the effects of a poor relationship with the teacher on decreases in engagement across the school year.

Academic coping as a protective factor

Multiple regression was also used to examine coping as a moderator of the relationship between poor relationships with teachers and decreases in engagement (see Figure 2, panel 3, Coping as protective). Both predictors, poor teacher relationships and child coping profiles at T1, were mean-centered before calculating the interaction term (poor teacher relationship × coping profile) to reduce the possibility of multicollinearity. Bootstrap estimation with 1000 samples was used to estimate standard errors. While poor teacher relationships and coping profiles at T1 were both significant predictors of engagement at T2 (β = .18, p < .001; β = −.12, p = .002; respectively) even when controlling for engagement at T1 (β = .59, p < .001), the interaction term did not reach significance (β = −.03, p = .223), indicating that coping did not act as a significant moderator of the risk of a poor relationship with the teacher on changes in student engagement.

Poor academic coping as a reciprocal process with risk

Potential feedback effects from coping to changes in the relationship with the teacher were investigated using multiple regression (see Figure 2, panel 4, Coping as reciprocal). Coping profiles at T1 were examined as an antecedent of poor teacher relationships at T2, adjusting for poor teacher relationships at T1. The regression coefficient from coping at T1 to poor teacher relationships at T2 was not significant (β = −.03, p = .236) when controlling for poor teacher relationships at T1 (β = .74, p < .001). Thus, there was no support for the idea that a more negative coping profile contributes to the worsening of relationships with teachers.

Academic coping as a mediator of the promotive effects of parent and peer support

To examine children’s coping profiles as a mediator of the promotive effects of parent and peer support (see Figure 2, panel 5, Coping as promotive mechanism), direct and indirect effects were tested using regression models and bootstrapping to determine the significance of the indirect effects. First, the direct effects of parent and peer support and poor teacher relationships at T1 on changes in student engagement across the school year were tested. Parent and peer support were both unique, significant positive predictors (β = .15, p < .001; β = .08, p < .04, respectively) and poor teacher relationships were a unique significant negative predictor of engagement at T2 (β = −.17, p < .001), while controlling for engagement at T1 (β = .53, p < .001). Second, parent and peer support and a poor teacher relationship at T1 were tested as predictors of children’s coping at T2, and all three were unique predictors in the expected directions with positive associations for parent (β = .25, p < .001) and peer support (β = .15, p < .001) and a negative association for poor teacher relationships (β = −.45, p < .001). Third, to test children’s coping at T2 as a potential mediator, it was added as a predictor of changes in engagement. Coping profiles were significant: They positively predicted engagement at T2 (β = .50, p < .001), while controlling for engagement at T1 (β = .45, p < .001). In addition, the effects of interpersonal promotive and risk factors were no longer significant (poor teacher relationship: β = .02, p = .729; parents: β = .04, p = .284; peers: β = .02, p = .592). Significant indirect effects from parent support, peer support, and teacher relationships were found with bootstrap estimation using 1000 samples (β = .13, p < .001; β = .07, p = .001; β = −.22, p < .001; respectively). Overall, these findings suggest that academic coping represents one pathway through which parent and peer support can promote students’ engagement.

Academic coping as a mediator of the protective effects of parent and peer support

To examine coping as a mediator of possible buffering effects of parent and peer support on the risk factor of a poor relationship with the teacher (see Figure 2, panel 6, Coping as protective mechanism), a moderated mediation model was tested using multiple regression with bootstrapping. Before the full moderated mediational model was examined, parent and peer support were investigated to see whether they moderated the effect of a poor teacher relationship on decreases in engagement. While parent, peer, and teacher relationships at T1 were all significant predictors of engagement at T2 (β = .13, p < .001; β = .08, p = .01; β = −.13, p < .001; respectively), neither the interaction term poor teacher relationship × parent support (β = −.02, p = .605) nor poor teacher relationship × peer support (β = −.01, p = .842) were significant over and above the autoregressive path from engagement T1 to T2 (β = .57, p < .001). Therefore, because parent and peer supports did not show protective effects, coping was not tested as a mediator.

Cumulative and compensatory effects of academic coping along with risk and support

Two pattern-centered strategies were used to examine whether academic coping provides cumulative or compensatory support. As a first step for both, a simple strategy was used to create subgroups, based on whether students were high versus low (i.e., above or below the median) on the risk factor (a poor relationship with the teacher, median = 2.01) and the two potential supports (i.e., parent support, median = 3.62; peer support, median = 3.50). Then eight subgroups were created that showed different combinations of cumulative risk and support, ranging from high risk (a poor relationship with the teacher combined with low support from parents and peers) to no risk (a good relationship with the teacher combined with high parent and peer support). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test whether students in these eight subgroups differed in their mean levels of engagement (see Table 3). The omnibus test indicated overall significant differences between groups, F(7, 1012) = 141.30, p < .001, partial η 2 = .49. As expected, main effects were found for relationships with teachers, F(1, 1012) = 310.76, p < .001, partial η 2 = .24 (M = 3.01 vs. 3.30 for students high vs. low in poor relationships); parent support, F(1, 1012) = 25.06, p < .001, partial η 2 = .02 (M = 3.20 vs. 3.11 for students high vs. low in parent support); and peer support F(1, 1012) = 70.30, p < .001, partial η 2 = .07 (M = 3.24 vs. 3.07 for students high vs. low in peer support). Not every subgroup was significantly different from every other, but consistent with a gradient of risk, mean levels of engagement were lowest for groups highest in risk (three risk factors: a poor teacher relationship combined with low supports from parents and peers; M = 2.87), whereas engagement was higher for subgroups with fewer risk factors – only two (M = 3.07) or one (M = 3.25), and highest for the subgroup with no risk factors (a good relationship with the teacher and high support from parents and peers; M = 3.42).

Table 3. Mean levels of engagement as a function of membership in subgroups experiencing different combinations of risk and supports

Note. N = 1020 third through sixth graders. All scale scores could range from 1 (“not at all true”) to 4 (“very true”). All between subgroup main effects were significant at p < .001.

Academic coping as cumulative support

To examine whether coping acted as a cumulative support for students with different combinations of risk and support (see Figure 2, panel 7, Coping as cumulative support), an ANOVA was used to test whether, for each subgroup, mean levels of engagement differed for students with high versus low coping profiles (median = 2.98). The results (see Table 3 and Figure 3) showed that, in general, they did, although not for every group. For six of the eight subgroups, students with higher coping profiles showed significantly higher engagement than students with the same combinations of risk and supports but lower coping profiles. The two exceptions were found in subgroups with two risk factors, where one was low support from parents. For these subgroups, trends were in the expected direction, but the difference between subgroups high and low in coping did not reach statistical significance. Hence, for most combinations of risk and supports, coping seemed to add cumulative support for student engagement.

Figure 3. The results of pattern-centered analyses of subgroups of students with different combinations of risk (high vs. low poor teacher relationships) and support (high vs. low support from parents and from peers) that examined cumulative effects of academic coping by testing whether subgroups showed mean level differences in their engagement as a function of whether coping profiles were high versus low. Note. N = 1020 third through sixth graders. Mean levels of engagement could range from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (very true).

Academic coping as a compensatory factor

To test for the compensatory effects of coping, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to see if subgroups with different combinations of risk and support still differed in their mean levels of engagement, when coping profile scores were added as a covariate. If academic coping can compensate for risk, then differences among subgroups in engagement should be reduced or disappear when coping is held constant. Results of the ANCOVA, F(8, 1011) = 269.54, p < .001, partial η 2 = .68, showed that all main effects were still significant, although the size of the effects were reduced. Main effects were still found for a poor relationship with the teacher, F(1, 1011) = 57.52, p < .001, partial η 2 = .05; parent support, F(1, 1011) = 8.89, p < .01, partial η 2 = .01; and peer support F(1, 1011) = 45.05, p < .001, partial η 2 = .04. Hence, little support was found for the notion that academic coping could completely compensate for differences between subgroups in their levels of engagement.

The complex role of academic coping in processes of resilience in student engagement

The last set of analyses combined findings from the variable-centered analyses into a full model depicting the role of academic coping in processes of resilience. The model that was tested, depicted in Figure 4, proposed that academic coping served as (1) a promotive factor, (2) a mediational pathway for risk, (3) a mechanism for other promotive factors with which it shows (4) some cumulative and compensatory effects, but not as (5) a protective factor itself, (6) a reciprocal process of stress generation, or (7) a mechanism through which other factors show protective effects. As expected, this model was a good fit to the data, and a better fit than models that included moderating (i.e., protective) effects of coping or parent or peer support.

Figure 4. The full model depicting multiple ways that coping is involved in processes of resilience in the academic domain during middle childhood and early adolescence, where the risk factor is a poor teacher relationship and the developmental outcome is academic engagement. Academic coping seems to serve as a promotive factor, a mediational pathway for risk, a mechanism for the promotive effects or parent and peer support, but not as a protective factor itself, a reciprocal process of stress generation, or a mechanism through which other factors show protective effects. All coefficients are standardized betas and significant p < .001. Dotted lines indicate pathways that were not significant, and so were deleted in the final model. Note. N = 1020 third through sixth graders.

Discussion

This study had two goals: (1) to propose a set of conceptual and empirical strategies for examining the role of coping in processes of resilience, and (2) to test their utility in the academic domain during late middle childhood and early adolescence, using a poor relationship with the teacher as a risk factor, and students’ engagement as a developmental outcome. Starting with the second goal, findings from the current study provided information both about poor teacher relationships as a risk factor, and about the role of academic coping in processes of risk and support. In terms of risk factors, it was clear that, in the academic context, having a poorer teacher relationship seems to exert downward pressure on students’ enthusiastic engagement in the classroom. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating that distant, conflictual, or otherwise low-quality relationships with teachers are both a marker of problems students bring with them and a potential hazard for students going forward (McGrath & Van Bergen, Reference McGrath and Van Bergen2015). In this study, a poor relationship with the teacher was operationalized based on the level of motivational support students reported. Students high on this risk factor reported that interactions with their teachers were characterized by more rejection (neglect, dislike), chaos (unpredictability, undependability), and coercion (control, intrusiveness). Such teacher-student relationships make it more difficult for students to get their needs met in the classroom, and so make it less likely that they will be cooperative, willing, or interested in teachers’ goals, listen to or comply with their requests, or internalize the value of the learning activities they assign (Gregory & Korth, Reference Gregory, Korth, Wentzel and Ramani2016; Martin & Collie, Reference Martin, Collie, Wentzel and Ramani2016; Quin, Reference Quin2017; Roorda et al., Reference Roorda, Jak, Zee, Oort and Koomen2017; Tao et al., Reference Tao, Meng, Gao and Yang2022; Wentzel, Reference Wentzel, Wentzel and Miele2016; Wigfield et al., Reference Wigfield, Eccles, Fredricks, Simpkins, Roeser, Schiefele, Lamb and Lerner2015), thus undermining their engagement. This risk factor may be especially salient over the transition to middle school when both students and teachers report normative declines in the quality of their relationships (De Wit et al., Reference De Wit, Karioja and Rye2010; Hughes & Cao, Reference Hughes and Cao2018) coinciding with the shift to a multi-teacher format where students take classes from more teachers for shorter periods of time.

Results from this study also indicate that academic coping plays a role in processes of resilience, and one that is relatively broad, acting both as a promotive factor and a pathway for risk and resilience. Findings from both variable- and pattern-centered analyses suggested that coping exerts promotive (but not protective) effects, serving to boost students’ engagement more generally and not just when risk is high. That is, coping was associated with an increase in students’ engagement over and above the effects of a poor teacher-student relationship, and in fact, as shown in the pattern-centered analyses, seemed to show promotive effects for most subgroups of students with different combinations of cumulative risk and support. At the same time, no combination of supports (including coping) could completely ameliorate the risk factor of a poor relationship with the teacher. Students high on this risk factor, even with the best combination of supports (a high positive coping profile plus high support from parents and peers) were significantly less engaged than students with better relationships to teachers who had all these supports.

Some comparisons in the pattern-centered analyses indicated that coping might even exert somewhat stronger promotive effects than parent or peer support, both of which can be considered standard resilience factors for many aspects of development (e.g., Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021; Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Stoddard, Eisman, Caldwell, Aiyer and Miller2013). For example, as expected, students in the subgroup with no risk factors showed the highest levels of engagement, but these levels were not significantly different from students with only one risk factor, as long as that risk factor was low support from either parents or peers. But students with only one risk factor, when that factor was poor relationships with teachers or low coping profiles, showed levels of engagement that were significantly lower than the no risk group. Hence, high coping and high support from one social partner could compensate for low support from the other social partner, but support from parents and peers, even together, could not compensate for low coping profiles or a poor relationship with the teacher.

Importantly, a positive academic coping profile seemed to play a role in resilience processes as a mediator or pathway of risk and promotion. Analyses including measures of poor teacher relationships and academic coping at the start of the school year indicated that both were unique predictors of changes in students’ engagement over one year of schooling; however, when coping at year’s end was tested as a mediator, it fully mediated the effects of a poor relationship with the teacher on declines in engagement. These findings suggested that one way a poor relationship with the teacher may undermine engagement is by making it more difficult for students to deal with academic challenges and demands, thus derailing their participation in difficult tasks. Examination of the effects of parent and peer support showed the same pattern: Both were promotive (but not protective) and coping fully mediated their effects on engagement, suggesting that parent and peer support may bolster students’ engagement by sustaining their tenacity when the going gets tough. After all, adaptive coping involves strategies like problem-solving and help-seeking, where parents and peers can participate directly (Skinner & Raine, Reference Skinner, Raine, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2023). Hence, the final model suggested that coping could be a pathway through which all three risk and promotive factors contribute to changes in engagement.

Limitations and future directions

The current study had several limitations – in sampling, measurement, and analytic strategy – which can be used to guide future research. First, the sample was homogeneous, comprised largely of white working- and middle-class students from one region of the USA. The role of academic coping may differ for students from other ethnic, racial, socioeconomic, or cultural groups, where more or different strategies may be salient (e.g., communal or identity-focused strategies; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Jones, Anyiwo, McKenny and Gaylord-Harden2019; Wadsworth, Reference Wadsworth2015); or its effects may be more pronounced for students who are dealing with additional risk factors (like discrimination or bias) that can undermine their motivation and engagement (Benner et al., Reference Benner, Wang, Shen, Boyle, Polk and Cheng2018; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Hope and Matthews2018). In terms of measurement, all the assessments in this study involved student reports, which may have biased findings due to common method variance. Although academic coping is generally assessed via student reports, both quality of student-teacher relationships and engagement can be measured via teacher-reports or observations (e.g., Hafen et al., Reference Hafen, Hamre, Allen, Bell, Gitomer and Pianta2015; Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Kindermann and Furrer2009). Future studies would do well to include this kind of supplementary information, and perhaps to compare the risk factor captured by students’ perceptions of their relationships with teachers to that of teacher or observer reports of these interactions. It may be that students’ perceptions carry more inherent risk, based on their connections to internal working models of relationships (Bretherton & Munholland, Reference Bretherton, Munholland, Cassidy and Shaver2008), but it could also be that teachers’ perceptions are more important since they guide teachers’ treatment of students.

This study was also limited by the choice of analytic strategy in the person-centered analyses, specifically, the use of median splits to create subgroups with different combinations of risk and support. This procedure was selected intentionally because of its simplicity, but it has disadvantages in creating subgroups that are discrete. Both “high” (above the median) and “low” (below the median) subgroups contained many students whose scores fell near the median. Such overlap may have made it more difficult to discern subgroup differences. Future studies would do well to consider the use of more complex a priori strategies such as tertile splits or absolute thresholds, or data-driven strategies such as latent profile analysis (e.g., Perzow et al., Reference Perzow, Bray, Wadsworth, Young and Hankin2021) to uncover subgroups that are more homogeneous and more distinct. Compared to those examined in the present study, such subgroups may show more systematic differences in their mean levels or changes in engagement.

Next steps for theory, research, and practice with academic coping

Theory and research on big R resilience can guide next steps for the study of academic coping in the face of risk in at least three ways. A helpful first step would be to think more about the status of a poor teacher relationship as a risk factor. In the current study, students generally reported a low mean level of negative interactions with their teachers, so it is worthwhile to question whether high scores on this indicator comprise “risk” or “adversity.” At the same time, a poor teacher relationship met the empirical definition of a risk factor, as a predictor of lower functioning and (at least short-term) motivational losses. Perhaps in future work, researchers could consider a more serious risk factor, such as prolonged or poor relationships with multiple teachers or even steeper than normal declines in relationship quality, as a marker for risky conditions in school. An alternative approach would be to focus on more molar forms of big R adversity, like homelessness, poverty, or parental impairment, and consider how they enter the academic domain. It may be that these adversities exert some of their effects by making it harder for children and adolescents to form close and caring bonds with their teachers. If academic engagement is a promotive factor at least in part because schools can serve as sanctuaries for students (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Nelson, Gillespie, Christenson and Reschly2022), especially those whose home lives are harsh or unpredictable, then strong positive relationships with teachers are likely one mechanism that creates and maintains students’ connections to these protected spaces. Hence, poor relationships with teachers may be a particularly deleterious risk factor for students dealing with more molar forms of adversity, especially if those are located in the home and family.

A second way to follow the lead of work on resilience would be for future studies to consider a wider range of student outcomes. The construct of engagement provided a good starting point, given its own protective and promotive effects (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Nelson, Gillespie, Christenson and Reschly2022). At the same time, however, a number of other motivational targets may also be relevant, including tenacity, buoyancy, grit, and reengagement, all of which may be markers of “little r” motivational resilience (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Graham, Brule, Rickert and Kindermann2020). And since it is the academic domain, future studies could also include key educational outcomes, such as learning and achievement, as indicators of functioning and competence. Third, following another lead from resilience research, future investigations could build on the current study’s design by extending the number of measurement points. The two included in this investigation were an improvement over typical cross-sectional designs, but in order to examine the role of coping in resilience processes that shape longer-term development, it would be helpful to chart individual pathways of engagement, motivation, and competence over multiple school years.

Implications for practice

Study results also have implications for parents, educators, interventionists, and others who want to support students’ academic development. First, like all research on risk, they suggest that a priority for improving students’ outcomes (in this case, their enjoyment and participation in school) is to reduce risk, in this case, to actively support the establishment and maintenance of high-quality teacher-student relationships (e.g., Kincade et al., Reference Kincade, Cook and Goerdt2020). Second, findings underscore the importance of supports from other social partners, like parents and peers, implying that adults can work together to support children and adolescents and to help students build positive relationships with classmates and peers. Third, focusing on academic coping, this study also suggests that all these relationships may have an impact on students’ engagement by either undermining or promoting the way students react when they run into difficulties in their academic work. As a result, academic coping may represent an important target for intervention. Programs designed to teach or coach coping, or in other ways help students develop a repertoire of productive strategies for dealing with problems and setbacks in their schoolwork, could help maintain or enhance their engagement over time.

The development of academic coping skills, like coping in all domains, seems to be based in interpersonal systems in which children learn to cope by coping together with more skilled others (Skinner & Raine, Reference Skinner, Raine, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2023; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2007; Zimmer-Gembeck et al., Reference Zimmer-Gembeck, Kindermann, Gardner, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2023), suggesting reasons why poor teacher relationships are negatively linked and supportive parent and peer relationships are positively linked to adaptive coping profiles. Like other research on resilience (Masten, Reference Masten2021), complex models of academic coping suggest that a multisystemic intervention would be most effective, one that targets not only students’ coping, but also the key relationships that will continue to foster its healthy development. Such interventions can be informed by systems theories of academic coping (e.g., Skinner & Raine, Reference Skinner, Raine, Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2023) as well as by research on how to promote positive relationships in the classroom and at home (e.g., Masten, Reference Masten2021; McGrath & Van Bergen, Reference McGrath and Van Bergen2015).

General models of coping as a part of resilience

Finally, apart from their implications for coping and development in the academic domain, study findings can be used to make progress on this paper’s primary goal: to identify a set of general strategies that can be utilized to examine the role of coping in processes of resilience across domains and developmental levels (depicted in Figure 1 and Table 1). Overall, and perhaps not surprisingly, based on their decades of use in work on resilience (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Lucke, Nelson and Stallworthy2021), the seven strategies proposed here were helpful in guiding a systematic examination of ways that coping might participate in maintaining high value developmental outcomes in the face of risk. Taken together, these strategies can “jump-start” the work of both coping researchers and resilience researchers interested in coping, providing an initial theoretical and empirical menu of possibilities for exploring coping’s functioning in other domains and during other ages. From this study, we can recommend beginning with coping profiles, rather than individual ways of coping (as are often the focus of coping research). Profiles reflect a repertoire of ways of dealing with challenges and problems that capture the balance between constructive and unproductive ways of coping. Researchers can always follow up on analyses of coping profiles to see whether there are specific ways of coping that seem to be exerting the biggest impact, either enhancing or undermining short- and long-term development.

Coping and resilience researchers can also look more deeply into why and how coping exerts its generally promotive effects. As in the examination of most resilience factors, we think it is important to acknowledge coping as both a marker of and a player in development (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2016). On the one hand, possession of an adaptive profile of coping is a developmental accomplishment, representing an age-graded history where much has gone right: (1) neurophysiological advances that have turned down stress reactivity and allowed (2) the establishment of secure relationships with caregivers and others, (3) the construction of executive functions and other regulatory capacities that can operate effectively during “hot” stressful conditions, and (4) the motivation, desire, and willingness to figure out how to deal with challenges and setbacks. So, when we see differential profiles of adaptive coping, we can surmise a great deal about the bio-psycho-social histories of children and youth, which can be contributing much to their current stress resistance and resilience.

On the other hand, we are convinced that coping is also a crucial player in processes of resilience, a form of “host resistance,” that serves an omnibus promotive function by taking the myriad daily stressors that enter the lives of children and youth, especially those in adverse circumstances, and converting them into grist for potential growth. For resilience researchers, a focus on coping invites the careful examination of whether and how big R adversities, like poverty, discrimination, or harsh families, disrupt children’s lives and make stressors of all kinds, including falling behind academically, more likely. The presence of these everyday adversities evokes stress reactions and coping, which have the potential to shape the short- and long-term effects of these stressors on children’s and youths’ functioning and development more generally.

It is important to note that systems conceptualizations do not view coping as an individual capacity or trait, but as a bundle of flexible actions emerging from a bio-behavioral base embedded in interpersonal interactions and relationships (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Reference Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck2016). Children learn to cope by coping, so stressful transactions are both a site of potential problems and of potential development. An explicit consideration of coping may help resilience researchers build out “challenge models” (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Stoddard, Eisman, Caldwell, Aiyer and Miller2013), by focusing on coping episodes as one set of experiences that can potentially contribute to the development of stress resistance, inoculation, and steeling (Rutter, Reference Rutter1981, Reference Rutter1987). Coping research provides a description of the kinds of transactions that trend toward positive growth: when stressful encounters are within the zone of just-manageable challenge, scaffolded by developmentally attuned resources, allow multiple attempts (including coping failures) to be used for learning, and where post-coping discussions favor a growth mindset and preparation for futures stressful encounters. Establishing these conditions on an ongoing basis, especially in the context of adversity, presents a challenge to the adults in children’s lives, and suggests that the coping of their adults may turn out to be a crucial resilience factor for children and youth.

Conclusion: development of coping within a resilience framework