Sydney Brandon was appointed the Foundation Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Leicester in 1975. As such he was one of the last of that generation of pioneering professors of psychiatry in undergraduate schools that had bloomed in the preceding decade or two. He was also one of the smaller group of professors who had the opportunity of contributing to the creation of a new medical school. From the beginning in Leicester he was a notable wheeler and dealer for the university, for the school and for his subject. His leadership of the then innovative ‘Man in society’ course ensured that the psychosocial perspective on health and disease was emphasised from the start of each student's career. His cajoling and corralling shaped up local psychiatric services in time to receive the first students in their clinical clerkship. No one could ignore Sydney and anyone who sought to cast psychiatry in a Cinderalla role had to reckon with him. His enthusiasm and energy were infectious. A quarter of the first cohort of Leicester undergraduates opted for a career in psychiatry. At least one is now a professor.

A proud Geordie, Sydney started his medical career in Newcastle. Before medicine he had lied about his age to get into the RAF at the end of the war and briefly toyed with a career in aeronautical engineering. Years later he took a great delight in the high honorary rank that came with his role as psychiatric advisor to the RAF. He worked in paediatrics and research in child development before settling into a career in psychiatry. Time in the USA and Manchester led up to his appointment to Leicester.

His achievements were many as a researcher and scholar. His work was wide ranging but was always practical and rooted in clinical work. The Leicester trial of electroconvulsive therapy was a notable achievement, not only academically but also as an exercise in persuasion and inspiration. All his consultant colleagues in Leicester agreed to allow all of their eligible and consenting patients to enter the study. But then, Sydney was a charismatic leader and forceful manager, although not in the modern style. Toward the end of his career the new managerial enthusiasm was on the rise but its modes and mores were not to Sydney's taste. His favoured planning tools were malt whisky and the back of an envelope, although he could work a committee expertly when it was necessary. And he took his role as a clinical leader seriously. He made no marked or unnecessary distinction between the role of the university and the NHS. To him both were organisations that should serve patients by promoting good practice and good practitioners. On the back of his office door was pinned a leaflet from the 1940s exhorting the virtues of the, then, new health service. He was an NHS man through and through.

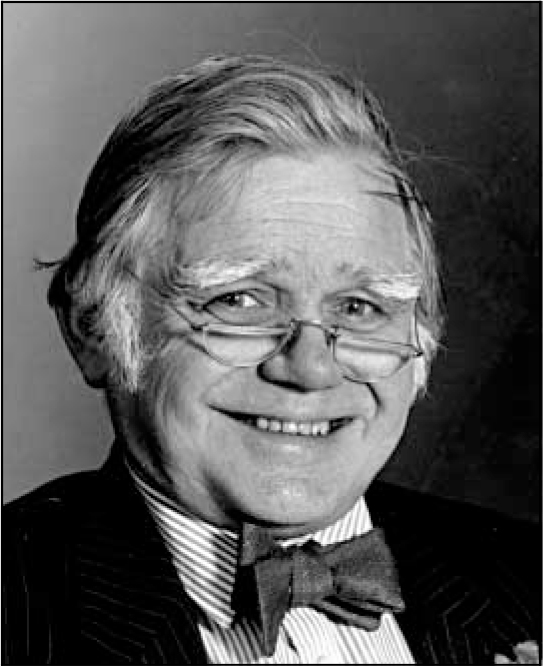

It was as a humane and skilled clinician that Sydney really shone. He cared about people — his patients, their families and his colleagues. He was involved in the best sense. Every inch the consultant but also down to earth and not at all ‘posh’, he was more likely to irritate his peers than his patients or those in less elevated roles. He was a dapper figure. He once published an article on ‘what every young man should know’; it gave instruction on how to knot a bow-tie — his habitual neckwear. Once at a formal dinner he was shocked and upset to find me wearing a ready-made bow-tie. Such sloppy short cuts were not for him either in dress or in clinical work.

He ended his formal career as a postgraduate dean. He was also a vice-president of the College. In so-called retirement he continued to work hard, energetically contributing to work with sick doctors and to the charity Childline. He made many trips to Rwanda, advising and contributing to aid work in the aftermath of the genocide. He always had plans for the future. He was a medical collector and amateur historian. He lived in a house that verged on being over-whelmed by his collection of feeding cups, instruments and medical memorabilia. He had hoped to write a book on the history of military psychiatry. Unfortunately, like his hope of mastering the French language, that ambition remained unfulfilled.

Sydney was a delightful companion and colleague. He was a family man and is survived by his two daughters, one a lawyer and one a doctor. Over the years, despite various illnesses, he seemed to remain the same. Only during his final struggle with ill health did his twinkle begin to grow dim. He died on 5 December 2001, leaving a sad gap but also happy memories and a continuing influence.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.