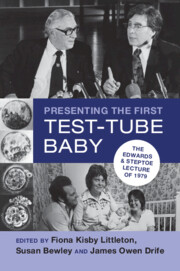

On 26 January 1979, Patrick Steptoe and Robert Edwards gave their first formal public presentation of the research that had led to the birth of Louise Brown in July 1978. Their lecture was a major event. Up until then, they had published no details of the successful outcome (pregnancy followed by live birth) of their pioneering work on in vitro fertilisation (IVF), except for a short letter in The Lancet in August 1978. On that snowy day in January, a capacity audience of four hundred or so crowded into the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) in London to hear how they had achieved their epoch-making success.

The lecture was unscripted but was recorded on a cassette tape, which, along with the lecture slides, was retained in the RCOG archives in Regent’s Park. No transcript was made, although individuals did ask for copies of the recording, which were sent around the world. Detailed accounts of the research appeared in print in September 1980, when three articles were published by Steptoe, Edwards and other members of their team in the British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. The world of medical science moved on.

That cassette and its accompanying slides lay almost undisturbed for forty years, until they were rediscovered by a medical historian, Fiona Littleton, shortly before the RCOG prepared to move to new premises in 2019. Using the tape, Dr Littleton painstakingly reconstructed the full and annotated transcript which sits at the heart of this volume. It presents the contemporary words of the two men who had spent a decade working together, often in the face of considerable opposition from their professional peers. It shows them feeling able, at last, to talk directly and publicly to their colleagues at the heart of the speciality of obstetrics and gynaecology.

Formal recognition, however, was still slow in coming. Steptoe was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) just before his death in 1988. Edwards was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2010 but was too ill to attend the ceremony. He was knighted a year later and died in 2013 at the age of eighty-seven.

Now, more than forty years after the birth of the first test-tube baby and more than fifty years after the beginning of the research in Oldham, Lancashire, it seems a timely moment to publish this celebratory edition of a key text in the history of human reproduction and make it accessible to a global audience.

We have tried to bring the lecture to life by placing it in context and establishing its place as a pivot in those early years between the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of IVF’s birth and the subsequent implementation of IVF all over the world. The scholarly work of a medical historian involves more than uncovering precious documentary evidence. There is a discipline to independently triangulating facts and their interpretation. In this case, this process has involved active research in television and newspaper archives, as well as seeking out reminiscence and oral history. So far, most ‘look-backs’ about assisted conception have come from involved personnel with their strengths of ‘insider information’ but weaknesses of memory and bias. These are still relatively early days in the historical arc of judging assisted reproduction which will be considered over and again by many generations to come. The newly opened Edwards Archives in Cambridge have been a useful resource. History also involves examining the long-term effects of events and their impact on the future. The consequences of IVF were world changing and are still unfolding.

Fiona Littleton’s chapter provides new historical material on the provenance of the lecture and adds fresh insights into the biographies of both Edwards and Steptoe. It describes the initial and subsequent coverage of the first ‘test-tube baby’ in print and broadcast media and sheds new light on the activities of Edwards and Steptoe in the period between the ending of their original Oldham research work and the opening of their new clinic, Bourn Hall in Cambridgeshire, in autumn 1980. It also reveals the crucial role of the print and broadcast media in documenting their activities using sources that have hitherto received scant attention in published writings on this subject.

As a result of this work, a new primary source of oral history was created in the form of an hour-long Reminiscence Event in 2019, which has been transcribed verbatim as Chapter 4. This formed part of the last RCOG public event to be held in the same hall in which Steptoe and Edwards had delivered their lecture. It involved ten members of the original audience, who were invited to talk about their impressions of the meeting forty years before. Not only does this provide new evidence on the reception of the lecture and the way it was understood and viewed at the time; it also provides corroborative evidence about other matters related to the work and the professional standing of Edwards, Steptoe and their IVF team in Oldham.

This reminiscence from professionals is complemented by one from Jan Barker, an Oldham journalist who was a member of the local team who broke the story and obtained the very first scoop on the world’s first ‘test-tube baby’. Steptoe was her own mother’s gynaecologist, and one of his colleagues mentioned in the Reminiscence looked after her own twin pregnancy. She shows how, to some extent, the local paper was interested simply in reporting local events rather than – as is so often portrayed – being antagonistic to Edwards and Steptoe. Her chapter gives a new perspective, reveals new aspects of biography and research and sheds light on those formerly hidden from view. It also reminds us that local papers are important to democratic societies and that events of global significance have humble beginnings that are so often rooted in, and have an impact on, the communities living close by.

Although focused mainly on a specific point in time, the book also includes a bridge from then to now. It provides hitherto unpublished information on the transitional years when the work of the original team began to change direction, giving rise eventually to routine medical treatments now available to millions of women and men around the world. Peter Braude and Martin Johnson, a doctor and a scientist, were young researchers working with Robert Edwards at Cambridge who have witnessed these changes from the inside. Professor Johnson wrote Edwards’s citation for the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. They are uniquely placed to write the book’s final chapter, surveying the many medical and scientific possibilities, and ethical issues, to which the Oldham work will continue to give rise in years to come.

We are thrilled that this unique book brings to light a key document in the history of obstetrics and gynaecology and adds to the growing historical record about the development of IVF in Britain in the 1970s. Previously unknown sources have been uncovered, transcribed and analysed. New evidence has been added to the historical record from original eyewitnesses. The original slide images demonstrate ‘state-of-the-art’ illustration in 1979, well before the routine use of computers, graphics programs and the Internet: all these provide the authentic ‘feel’ of a clinical and scientific presentation of the times.

Lastly, and importantly, we connect the past to the present and the future by examining the medical and scientific possibilities, and ethical issues, that those working in this field may yet encounter in the decades ahead. We hope this book will educate all doctors and students with an interest in reproductive medicine, people with an interest in the history of medicine and the informed general public – particularly anyone who has undergone IVF, had a child by IVF or been a child conceived by IVF in the last forty years.