The discussion of narrative in mashups is typically focused on how a preexisting message is reinterpreted by the incorporation of new musical material.Footnote 1 This reinterpretation often significantly changes the perception of the narrative in dramatic ways ranging from the subversive to the poignant. However, the message of most mashups is ultimately restricted to the borrowed sources by the very nature of their construction: Large portions of preexisting lyric tracks are borrowed and fused with another track, which engenders a comparison of the works on both narrative and aesthetic grounds.Footnote 2 Many scholars remark that the megamix mashups of DJ Earworm break free of these narrative shackles by employing a distinct musical construction. As opposed to fusing together the typical two to three different songs, DJ Earworm's mashups combine hundreds of small samples from ten to fifty different tracks in order to create a work with an original message.Footnote 3

In his various interviews, DJ Earworm states that his United State of Pop (USOP) series of mashups are intended to be “musical time capsules that capture the zeitgeist of the age.”Footnote 4 However, this provocative claim has never been explored in any depth by the artist nor have any of the works been analyzed for their meaning by scholars. This raises the question: To what degree do DJ Earworm's mashups reflect cultural issues in U.S. society?

In assessing this question, this paper explores the messages espoused by these mashups and the complexity of their narratives. In terms of evaluating the message, this study primarily uses Zbikowski's concept of conceptual integration in music to assess how meaning is created through the interaction of various multimedia elements, including the music, lyrics, and visuals.Footnote 5 According to DJ Earworm, this examination should reveal a clear relationship between the message of the mashup and events in contemporary U.S. society. However, these narratives are not always readily apparent because the ability to create a clear message is significantly limited by the complexity of fusing together hundreds of lyric splices drawn from up to fifty different borrowed tracks. As I will show, the combined exploration of the lyrical, musical, and visual content greatly increases the clarity of the mashup's narrative. In terms of exploring the complexity of the narrative, this study primarily uses Almén's theory of musical narrative to assign a narrative archetype to each mashup and analyze their narrative journeys.Footnote 6 Naturally, DJ Earworm's mashups would be considered complex if he uses a variety of narrative archetypes and if the interaction of each mashup's narrative forces (i.e., the order and transgression) is dynamic rather than static.

These analyses reveal that DJ Earworm's mashups show a consistent pattern of having complex narratives with cultural messages that resonate with contemporary issues in U.S. society, including fossil fuel dependence, income inequality, and political and racial division. Accordingly, they reinforce and inform previous research which argues that DJ Earworm's mashups are distinct within the mashup corpus because they create original narratives instead of subverting, reinforcing, or altering narratives from preexisting works.

A factor that unifies most mashups is that their meaning is primarily derived from a preexisting work. The most common and researched type of these mashups is the A vs. B mashup that combines two to three different songs. In terms of construction, one song or an alternation of sections from two songs typically provide the lyrics, whereas another song provides the accompaniment. As many scholars have shown, the most common aesthetic result is that the original message in the lyric track is subverted by the accompaniment track.Footnote 7 Brøvig-Hanssen and Harkins state that this subversion is the result of the opposition of musical congruity and contextual incongruity.Footnote 8 Musical congruity involves carefully aligning the songs in terms of melody, harmony, meter, and tempo to create an aesthetically pleasing song that warrants an exploration of the compatibility of the two tracks in other parameters. Contextual incongruity takes advantage of this exploration by revealing that the narrative elements are in opposition, which often comes in the form of a perceived high–low genre opposition.Footnote 9 For example, in one of the earliest hit mashups, Smells Like Teen Booty by 2manydjs, Nirvana's grunge-era anthem “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is fused with 2001's pop hit “Bootylicious” by Destiny's Child. In this case, the depressing grunge-era themes and raw sound are opposed by the playful themes and slick electronic production of early 2000s pop.Footnote 10 Looking at literary theory, this subversive effect can be understood under Genette's concept of travesty: “The rewriting of some ‘noble’ text as a new text that retains the fundamental content but presents it in another style in order to ‘debase’ it.”Footnote 11

Tom Johnson challenges the idea that all mashups are subversive by showing how combining tracks from similar stylistic registers results in a positively reinforced narrative. That is, mashups with both musical and contextual congruity are not subversive, ironic, or humorous. For example, Johnson explains that the similarity of genres in DJ Earworm's No One Takes Your Freedom allows the mashups to assert a tragic-to-transcendent narrative. First, he notes how the musical congruity is paired with sincere, narrative-rich lyrics, which “are all basically concerned with consolation and advice after a breakup, presented in what Lori Burns would call direct communication (clear ‘I/you’) and sincere expression.”Footnote 12 Second, he notes how a potential collision of rock and gospel genres proceeds to a fused rock–gospel genre, in which “a cooperative interaction method results, effected by the shift from a baroque–pop topic towards one of plentiful gospel, passed through the filter of a general rock topic.”Footnote 13 This more cooperative relationship between the borrowed tracks can also be used to alter the original message without necessarily subverting it. For example, the replacement of Jay-Z's original beats in his rap “What More Can I Say?” with the accompanimental track from The Beatles's “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” in Danger Mouse's Grey Album significantly shifts the meaning of the title lyrics from a more triumphant statement to a more resigned one.Footnote 14 The use of the lament bass of The Beatles's “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” reinterprets and elevates the previously triumphant lyrics of Jay-Z's “What More Can I Say?” from “a statement meaning not that nothing more needs to be said, but that nothing more can be said.”Footnote 15 Outside of the scholarship on mashups, the idea that an original work can be either subverted or elevated by a new accompaniment is already shown in Butler's analysis of narrative in two Pet Shop Boys covers.Footnote 16

What is not seen in the previous mashups is the ability to create a truly original message. As Adams mentions in his article on Danger Mouse, these original messages can be found in the works of DJ Earworm, one of the most popular and analyzed mashup artists today.Footnote 17 His breakout mashup, Blame it on the Pop (2009), garnered nearly fifty million views on YouTube and his subsequent mashups have averaged nearly ten million views each. Accordingly, many of his mashups have received play on top forty radio stations in both the United States and Canada and were listed on the Billboard Top 40 charts. This popularity has resulted in a long career as a highly sought after audio–visual mixer, who has been employed by Google (for their “YouTube Rewind” series 2013–14), the 2012 London Olympics games, and various pop artists, including Carrie Underwood, Backstreet Boys, and Nelly Furtado. He has also been featured on many major media outlets, such as CNN, NPR, Time, Billboard, and Vox, and his work discussed by many academic scholars.

In these media interviews, he frequently mentions the importance of music theory to aspiring mashup artists, saying, “If you're young, study music. Study music theory. That's the number one thing”Footnote 18 and “STUDY MUSIC THEORY … LOTS.”Footnote 19 This focus of music theory likely comes from his time at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where he double majored in computer science and music theory.Footnote 20 His affinity for musicology is also indicated in his book on mashup composition, which dedicates an entire chapter to the history of musical borrowing, spanning thirteenth-century motets, Renaissance quodlibets, and well-known canonical composers including Bach, Mozart, and Ives, and ending with a discussion of current digital sampling techniques.Footnote 21

In fact, DJ Earworm's mashups involve a high degree of craftsmanship that emulates many borrowing procedures documented in Peter Burkholder's study of Charles Ives. The first is the use of borrowed material to signal a section's formal designation, which Burkholder asserts in his analysis of Ives's Second Symphony:

The borrowed material is not inserted into an existing framework but forms the very basis of the music […] Every one of his themes paraphrases an American vernacular tune […] At the same time, many transitional sections […] paraphrase transitions or episodes in the music of Bach, Brahms, or Wagner.Footnote 22

The clearest example of Burkholder's claim is found in his analysis of the opening of Ives's Second Symphony, movement II, in which each thematic area is based on a different tune from the United States, whereas the transition is based on the second transition of Brahms Symphony 3, II.Footnote 23 As shown in my own previous analysis of Together as One, DJ Earworm also underscores the sections of his mashups with borrowed material by correlating the formal regions of the borrowed material—in both lyric and accompanimental samples—with their formal location in the mashup.Footnote 24

This practice holds true in DJ Earworm's more intricate mashups, such as his yearly USOP. Although the most common (i.e., basic) mashups typically employ an average of two to three different songs, the mashups in DJ Earworm's USOP series incorporate each year's twenty-five most popular songs—except for 2015's 50 Shades of Pop that uses fifty songs. To fit all these songs into the span of a standard pop song, both the lyric and accompaniment tracks feature multiple splices per section. The lyric track accomplishes this by laying different splices next to each other, which results in original, coherent lyrics. The craftsmanship of these lyrics can be seen in the chorus of DJ Earworm's 2012 entry from the USOP series, Shine Brighter (see Figure 1), which features seven samples from four different songs that maintain proper grammar and a singular narrative focus (proactive optimism). The accompanimental track incorporates more samples by mixing accompaniment layers from different songs.

Figure 1. Analysis of lyric splicing in DJ Earworm's first chorus of “Shine Brighter” (2012).

Furthermore, DJ Earworm proclaims that the lyrics in his USOP series intend to capture the major cultural themes of their given years. In multiple interviews, he states how he attempts to capture the zeitgeist of the year in his mashups. In one, he states, “I thought, would it be cool to take a bunch of songs from a single year and mash them all up together to make a sort of musical time capsule capturing the zeitgeist of the year.”Footnote 25 In another, “I got much more of a feeling of responsibility to relate to the zeitgeist.”Footnote 26 In a later interview, he underscores his intentionality in relaying each year's central cultural theme by describing his creative process in determining each mashup's narrative: “I'll look up all of the lyrics for all the songs, and I put them on a single document. And I'll sort of scan through the document and try to identify my main thesis.”Footnote 27

Conceptual Integration in Mashups

There are a lot of limiting factors that go into creating the narrative of DJ Earworm's mashups. The lyrics must be selected from the top twenty-five songs of the year, they must feature cut up samples from multiple songs to adequately reference each song, they must be grammatically correct, they must create an aesthetically pleasing melody, and they must conform to a standard verse–chorus form.Footnote 28 In addition to this intricate web of factors, DJ Earworm states that they also convey the major cultural themes of each year. Being a multimedia work, the creation and perception of the narrative involves a consideration of every facet of the work: The lyrics, the music, the visuals, and, as I will later show, the borrowed sources themselves.Footnote 29

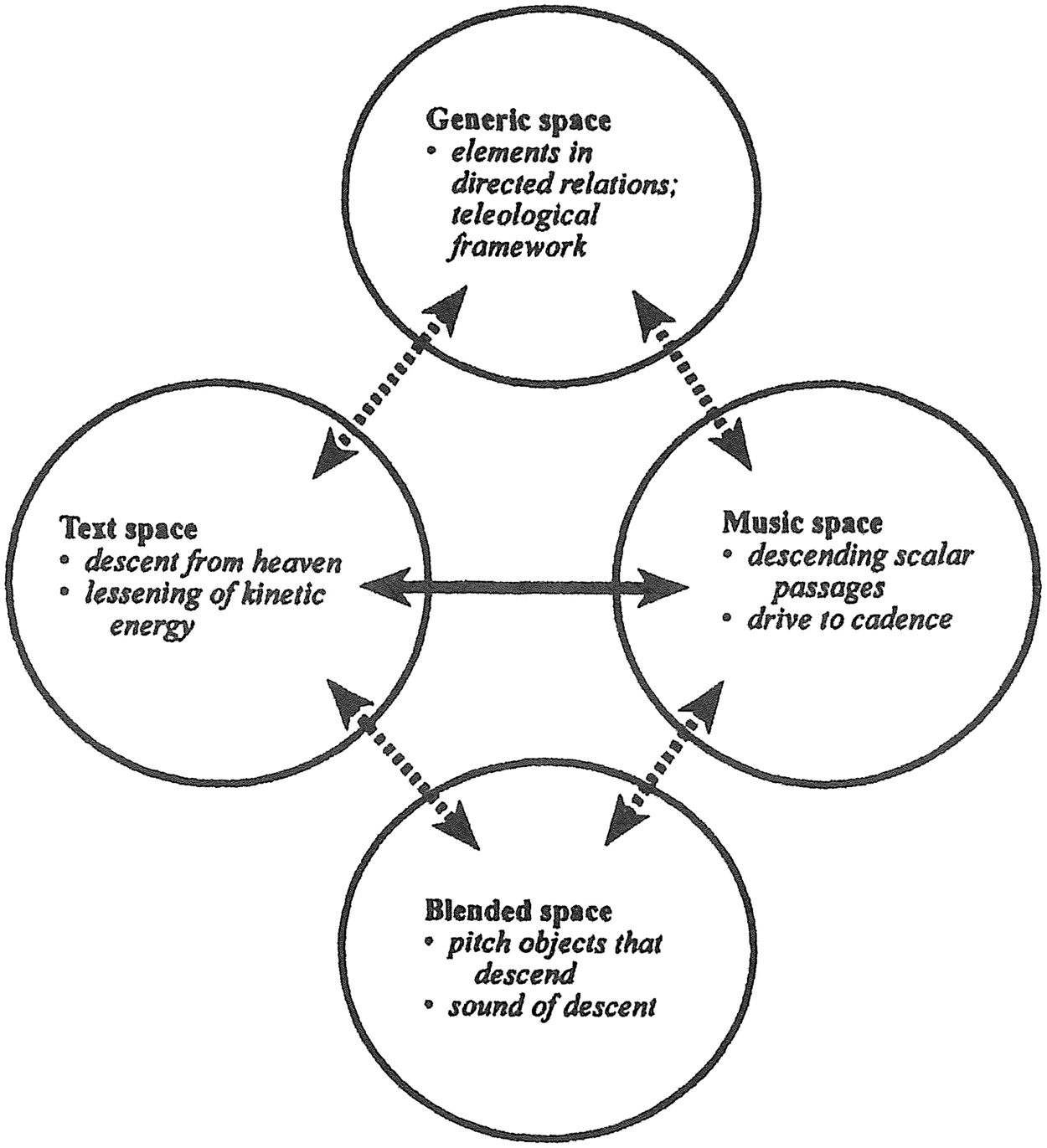

One prominent method of analyzing meaning in multimedia music is through the examination of the associations among each medium through Fauconnier and Turner's conceptual integration networks (CINs).Footnote 30 In a prototypical CIN, there are two input spaces (shown in the middle) that showcase the elements of each of the mediums that are being associated. The associations generated by their integration are shown in the blended space (shown at the bottom). For example, Zbikowski shows how the metaphor of PITCH as HEIGHT relates to text painting in Palestrina's Pope Marcellus Mass, Credo (Figure 2).Footnote 31

Figure 2. Conceptual integration of PITCH as HEIGHT in Palestrina's Pope Marcellus Mass, Credo. Laurence Zbikowski, Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 83. Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear.

The text describes a descent from heaven, which correlates with a descent in pitch. The generic space (shown at the top) clarifies the types of elements being correlated. In this case, this diagram only shows associations regarding each medium's vertical elements and their teleological trajectory. In creating the blend, Fauconnier and Turner state that three basic processes occur: (i) Composition, in which the blend creates new associations and entities; (ii) completion, in which the newly formed associations and/or entities can be used to create abstract interferences; and (iii) elaboration, in which the inferences can be applied to specific situations.Footnote 32 In the Palestrina example, composition associates the descent in the text with the descent in pitch. From this, completion may abstract this inference to assume that texts related to highness or lowness would be associated with high and low pitches, respectively. Finally, elaboration would extrapolate that a text of “ascendit” would feature a rising pitch contour. As Zbikowski shows, this is precisely what happens at the end of this movement of Palestrina's mass.Footnote 33

Once an association between one or more input spaces is forged, scholars have shown how signifiers that are unique to one input space can be brought into the blend.Footnote 34 In film scholarship, Marshall and Cohen state that the interpretation of the music and film is not purely based on their overlap.Footnote 35 As their diagram shows, the interpretation (represented by “ax”) must involve the area of overlap between the music and the film (represented by “a”) but may also involve aspects unique to the music sphere (represented by “x”) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Diagram of multimedia interaction in film. Sandra K. Marshall and Annabel J. Cohen, “Effects of Musical Soundtracks on Attitudes Toward Animated Geometric Figures,” Music Perception 6, no. 1 (1988): 109. Reproduced with permission of University of California Press.

Zbikowski goes one step further by suggesting that once two mediums establish an association, one can bring elements that are exclusive to either medium into the interpretation, as seen in Zbikowski's nonmusic CIN for Eeyore of Winnie-the-Pooh fame.Footnote 36 In this example, two elements in each input space are being correlated, which both involve the subset of all possible human emotions being associated with prototypical donkey behaviors (Figure 4). Accordingly, the diagram associates a donkey's actions of being slow-moving and eating undesirable food with the human capacity for being gloomy and prone to endure discomfort, respectively. Once this association is formed, the blend brings in elements unique to each space to complete Eeyore. Eeyore gains his ability to think and talk from the human space, whereas the donkey space transfers Eeyore's physical form.Footnote 37

Figure 4. Conceptual integration network of Eeyore. Laurence Zbikowski, Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 79. Reproduced with permission of the Licensor through PLSclear.

Although these exclusive elements expand the possible signifiers and allow for the creation of new blends, the associated elements restrain the possible interpretations. Lakoff and Johnson state that metaphor models—such as CINs—highlight certain features while suppressing other possible readings.Footnote 38 Fauconnier and Turner's concept of conceptual integration echoes this statement by showing how conflicting elements are typically not brought into the blend.Footnote 39 Take for example the phrase, “He's so hot.” With no other context, this phrase could signify a male that is attractive, sick, or performing well athletically. Once one adds an associated image with this phrase, such as a dance club, a hospital room, or a basketball court, the most likely interpretation is highlighted and noncorrelating interpretations are suppressed.Footnote 40 Accordingly, when the phrase “He's so hot” is correlated with a hospital room it most likely indicates a patient has a fever, although it could be possible—although grossly inappropriate—that it could be referring to the patient's attractiveness.

The resulting ability of intersecting mediums to engender different interpretations is evident in Zbikowski's reading of two different settings of Wilhelm Müller's “Trockne Blumen” by Bernhard Klein and Franz Schubert.Footnote 41 Zbikowski states that Klein's setting of Müller's poem projects a less drastic shift to the joyful embrace of death than Schubert's setting. Although both employ a parallel, minor-to-major key change to signify the text's shift from sadness to joy, Klein's setting preserves the melody and accompanimental pattern throughout the piece, whereas Schubert features a change in melody and a dramatic shift from a stark accompaniment to a frenetic one. From this, Zbikowski suggests that Klein's preservation of musical material indicates that a singular persona has undergone a shift from sadness to joy, whereas Schubert's drastic changes in mode, melody, and accompaniment signifies a psychotic shift between two distinct personae.Footnote 42 Zbikowski identifies the crucial factor music plays in eliciting these two readings:

Are both millers present in Müller's poem? Yes and no. Yes, in that his poem can support these different interpretations, as the CINs above have shown. And yes, in that, from the perspective of the poetic cycle as a whole, the miller is a truly complex character, a quiet psychopath destined for destruction. But no, in that it requires the agency of the music to bring forth these specific millers.Footnote 43

Is Zbikowski's reading of Schubert's setting the only possible interpretation? No. The sudden shift could be attributed to something more specific—like a bipolar shift from being depressed to manic—or something more benign like a shift from a dismal reality to a blissful dream. Is Zbikowski's reading persuasive? Yes, the CIN clearly articulates the basis for the interpretation he puts forth. Accordingly, CINs are not a prescriptive model for showing how a combination of two mediums will yield a particular result. They are a descriptive model for showing the soundness and validity of a particular reading. For instance, the CIN for Eeyore was shown to be a well-constructed hybrid of a human and a donkey. However, not all donkey–human hybrids yield Eeyore, as one can easily see in the donkey transformation scene in Disney's Pinocchio. Accordingly, my readings of DJ Earworm's work will not suggest uncovering each mashup's true meaning but rather will put forth a hopefully persuasive interpretation that supports the DJ's claim that his mashups reflect each year's zeitgeist.

Because nearly every DJ Earworm mashup is a music video based exclusively on borrowed material, I will employ four different input spaces to capture each area contributing signifiers: Music, visuals, text, and borrowed meaning. The combination of music with visuals and text is seen throughout multimedia scholarship,Footnote 44 in which visuals and text are sometimes combined into a singular “film” space.Footnote 45 Although borrowing is not typically expressed as an input space,Footnote 46 it is frequently cited as an important contributor to the interpretation of a work in mashups.Footnote 47

Like visual and text input spaces, borrowing affects the interpretation of multimedia works through both its associations to the other input spaces and the projection of its original message.Footnote 48 As Burkholder shows, Ives's “Things Our Fathers Loved” has clear associations between the lyrics and the borrowed material.Footnote 49 The text implores one to listen for songs that have no words, in which the melody provides snippets of borrowed tunes without their original lyrics: “Now! Hear the Songs! I know not what are the words.” That is, the integration highlights the melody's use of borrowed material. Burkholder goes further by showing how the borrowed material adds meaning through the message of the original borrowed material. The text infers that these borrowed tunes represent the things that our Fathers loved, but it does not explicitly state what these things are: “But they sing in my soul of the things our Fathers loved.” Burkholder then explains how the borrowed material adds meaning:

Here is where knowing the texts for the songs Ives borrows adds meaning, for they name these values: home; the natural beauty of one's homeland; religious faith; patriotism and group feeling; and hope for a further reunion with those we love, in Heaven if not on earth.Footnote 50

To eliminate the bulk created by employing these four different input spaces, I will employ partial CIN diagrams that remove the generic space or simply present the conceptual integration in prose. As seen in Fauconnier and Turner's eponymous article on CINs, the analysis of conceptual integration does not require a diagram. Although full diagrams are common in music scholarship on conceptual integration,Footnote 51 they are rare in Fauconnier and Turner's first article on the subject.Footnote 52 Specifically, only one of the seven metaphors they explore in the article has associated CIN diagrams—and that one is a series of abstract images instead of text.Footnote 53 Instead, the authors predominantly unpack the blending entirely in prose, as I will do in my subsequent analyses.Footnote 54 I will, however, often display the input and blended spaces in order to highlight the key signifiers I reference in my interpretations, with the slight modification of displaying the input spaces in a quadrant with square boxes that allows for more text than circles (see Figures 5, 7, 8, 13).

Figure 5. Input and blended spaces for the chorus of No More Gas.

Beyond conceptual integration, there are two factors that will guide my interpretation of DJ Earworm's mashups. The first factor is the time period in which the mashup is published. As shown earlier, DJ Earworm claims that his USOP series attempts to capture the zeitgeist. Accordingly, each mashup's narrative should have some correlation with contemporary cultural events in the United States. The idea that songs encapsulate the era in which they were published has long been a mainstay of musicology, but recent articles by Keith Negus show how deeper narratives in popular music are revealed when considering the time period in which they were produced.Footnote 55 In his dismissive analysis of The Beatles’ “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” David Nicholls suggests that the song contains “no story per se in the lyrics, and as a consequence there is no element of narrative discourse in the musical setting.”Footnote 56 Nicholls's reading is easy to understand as the song simply reiterates a boy's love without any sense of progression or acknowledgment of the girl's response. Citing recent intertextual scholarship, Negus counters Nicholls's reading by stating that: “Songs do not convey narrative meanings as texts alone or in relation to the supporting conceptual package. Songs exist in relation to other songs. The practice of songwriting and acts of interpretation are embedded within grids of intertextuality.”Footnote 57 Negus supports this claim through the analysis of Barbara Bradley, which states that the narrative of “I Want to Hold Your Hand” is in dialogue with a common narrative within contemporary girl-group music:

The Beatles’ declarations of love in their first few hit songs did not come out of the blue nor are they simply a direct descendant of a line of male, or even boy-group, discourse. They are a response to, and in dialogue with, the voicing in girl talk by the Shirelles of the ubiquitous female request for men to tell women that they love them.Footnote 58

That is, contemporary girl-group songs requested that boys tell girls how they feel, and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” responds to this request.Footnote 59 Accordingly, a deeper understanding of the narratives of DJ Earworm's mashups will be gained by viewing them both within the year they were composed and in relation to other songs composed within that year.

Form is a second factor that guides the narrative of popular music. Many scholars have assigned common narrative roles to sections in popular music.Footnote 60 A succinct example of these roles is given by Jocelyn Neal, who writes:

Verse: “a section of a song […] whose text advances the basic plot.”

Chorus: “a section of a song whose text reflects statically on the main point of the song.”

Bridge: “a unit […] offering an alternative outlook on the storyline.”Footnote 61

Later in the article, she makes the keen insight that the chorus's static, reflective message is often dependent on the narrative advanced in the preceding verses. For example, the eponymous chorus refrain of Tim McGraw's “Don't Take the Girl” changes meaning drastically from (i) Dad, don't take my little sister fishing to (ii) Felon, don't rob my girlfriend to (iii) God, don't take my wife's life, depending on the story presented in the preceding verse. As in the mashups of DJ Earworm, Neal states that a chorus's lyrics may feature slight shifts to reflect their changing meanings.Footnote 62

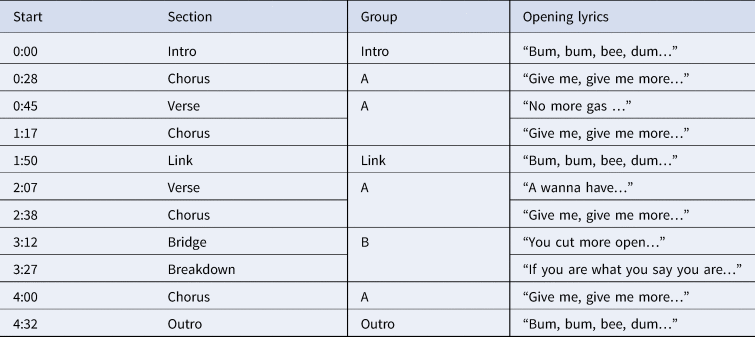

In order to show how conceptual integration and verse–chorus form create messages that relay the American zeitgeist, let us explore an early, non-USOP mashup: No More Gas (2008). As this mashup is not part of the USOP series, there is no reason to assume the mashup relays events in American society, nor has the composer ever discussed this work. That being said, No More Gas was released during the height of the American gas crisis of 2008, when oil reached its highest price in U.S. history (see Figure 10). The following narrative will show how one can argue for a culturally relevant message in DJ Earworm's mashups—without support from the composer—through its conceptual integration and the work's verse–chorus narrative structure. Furthermore, I suggest the narrative goes beyond a simple depiction of fossil fuel dependency by conveying the complex struggle of many Americans between the necessity for gas and the desire to rid themselves of fossil fuels (Table 1).

Table 1. Formal Diagram of No More Gas

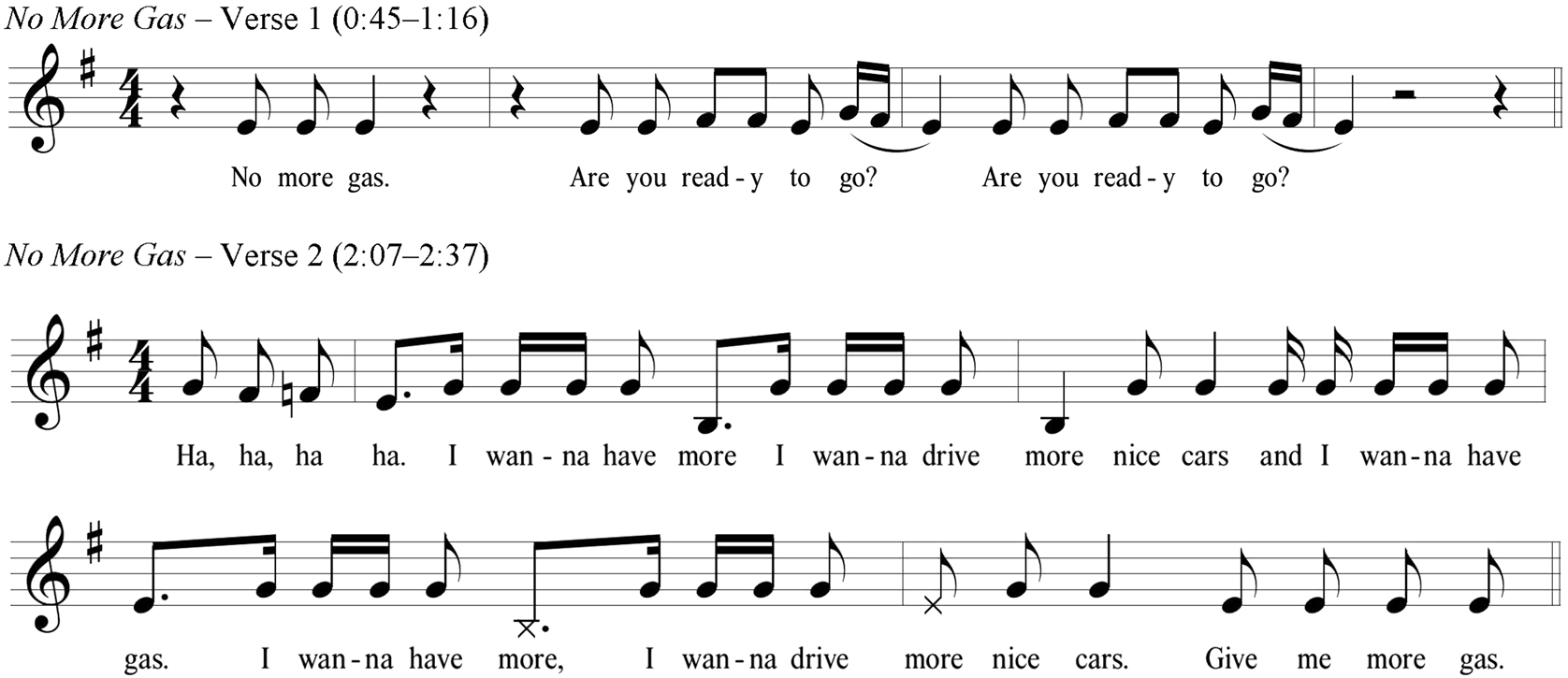

The narrative at the opening of No More Gas is exceptionally vague because the chorus appears before the opening verse, which means the chorus's static, reflective message has no verse to reflect upon. The chorus's preceding introduction warns of an unspecified danger through the lyrics “Dangerous, so dangerous! How you gonna fix it?”Footnote 63 (Figure 5). This sense of danger is further relayed by the music's use of minor mode and stark texture, the video's dark, distorted images, and the associated meaning from Rihanna's dystopian-themed “Disturbia.” However, there is no clear indication of what the danger is or how it relates to a lack of gas. The chorus continues the dark aesthetics of the introduction, but it fails to bring much clarity to the nature of the looming danger. The lyrics repeat, “American boy, give me, give me more. I just can't stop,” but it is not clear what they want given or what they cannot stop.Footnote 64 However, the lyrics do clarify that the danger relates to an obsessive desire, which correlates with the music's frequent melodic repetition. The visuals of dark or black and white images reinforce the idea that this desire is nefarious in some way. The two primary songs referenced in the chorus, Britney Spears “Gimme More” and Ne-Yo “Closer,” are both about a toxic relationship, which relates to the previous signifiers of danger and obsessive desire. However, as the following analysis will uncover, this is not a generic pop song about a boy–girl romance but an exploration of fossil fuel reliance in U.S. society.

As the opening lyrics of the following verse clarify, the object of desire is gasoline. Although the phrase “No more gas,” is often a metaphor for being physically spent, the visual space's saturation with images of cars highlights the literal gasoline those cars consume.Footnote 65 In addition, the music's long stretches of melodic silence and limited vocal range highlights the lyric's focus on the scarcity of gasoline (Figures 6 and 7). Finally, the frequent use of Rihanna's “Disturbia” and Madonna's “4 Minutes” associates the lack of gas with an ongoing dystopia and impending disaster, respectively.Footnote 66

Figure 6. Opening melodies of verses 1 and 2 in No More Gas.

Figure 7. Input and blended spaces for verse 1 of No More Gas.

Instead of continuing this narrative of scarcity over gasoline, the second verse's lyrics state an unyielding desire for more gas and cars. Like the previous verse, the visuals suggest a preoccupation with gas by saturating the visual space with images of cars and other gas-powered vehicles. Unlike the last verse, the music shifts to a frenetic vocal line that highlights the excitement over consumption, rather than the previous verse's stark texture that highlights exasperation with depletion (Figures 6 and 8). This narrative is then reinforced by the associated themes of narcissism and consumerism featured in the most heavily sampled song of the section, Pussycat Dolls's “When I Grow Up.”

Figure 8. Input and blended spaces for verse 2 of No More Gas.

Although the verses’ contrast of depletion and desire could suggest a muddled or ambivalent narrative, my interpretation is that these messages complement each other to represent the factors that result in high gas prices: Low supply and high demand (Figure 9). Accordingly, these complementary factors clarify the static, reflective message of the chorus. The verses’ narratives suggest that the chorus is about a toxic relationship between U.S. citizens and their reliance on gasoline, in which there is an intense demand for a limited supply of gasoline that engenders higher and higher gas prices.

Figure 9. Relation of verse blended spaces on chorus blended space in No More Gas.

This narrative would have been resonant to residents of the United States at the time this mashup was released because gas prices had just reached their highest rate in U.S. history. As shown in the graph from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, gas prices reached an all-time peak in the summer of 2008, which is when this mashup was released. The struggle with gas prices was the most viewed news story in the country, was seen as a significant contributor to the Great Recession, and was a constant theme in the 2008 election, which is captured by Sarah Palin's memorable refrain of, “Drill, baby, drill!” (Figure 10).Footnote 67

Figure 10. U.S. Energy Information Administration graph on U.S. gasoline prices over time.

Instead of demanding more oil extraction, the bridge of this mashup suggests an alternative response to the crisis: Reducing gas consumption. As stated by Neal, the narrative role of the typical bridge is to offer a contrasting or alternative outlook on the storyline.Footnote 68 The opening lyrics assert a rejection of fossil rules by stating, “You cut me open where the dinosaurs lay, and I know they love it. So, the hell with all that rubbish.” Naturally, this is a reference to gasoline, which is found deep underground as the result of long-decayed dinosaur bones. The seriousness of the situation is underscored by visuals that depict someone on life support and the music's dry accompanimental texture. The following breakdown section demands a call to action through the repeated lyrics, “If you are what you say you are American boy, how you gonna fix it?” The idea of breaking free from oil dependence is highlighted though a montage of a purple-clad Black man slowly busting free from a strapped chair. The music relays the insistence of this call to action through multiple repetitions, whereas the borrowed material from Lupe Fiasco's “Superstar” suggests that combatting the issues will make one a hero.

It is important to recognize the narrative complexity going on at this point. This piece could have captured the zeitgeist by simply portraying the United States’ problematic reliance on gasoline. However, the work goes deeper by showing the struggle for many in the United States between their need for gas and their desire to break free from this dependence. The complexity of this struggle can be neatly portrayed through Almén's narrative theory, which pits order-imposing hierarchies against order-opposing transgressions.Footnote 69 In this case, the order-imposing hierarchy is the United States’ negative reliance on fossil fuels and the positive transgression is the fight against this reliance. According to Almén's theory, the narrative could either be a comedy, if the transgression succeeds, or a tragedy, if the transgression fails. Naturally, the narrative at this point is unresolved because the song is not at its conclusion. That is, this “American boy” has been encouraged to be a superstar by opposing fossil fuel, but there is no confirmation on whether he acts on this motivation or succumbs to gas dependency.

The subsequent reemergence of the chorus, however, suggests that the bridge's contrasting narrative of breaking free from an obsessive reliance on oil fails. With the arrival of the chorus comes its narrative of hopelessness in breaking free from gas dependence, which leads to an outro whose lyrics of “Dangerous, so dangerous!” suggest that the problem persists—which it did and still does. Accordingly, this piece is ultimately a tragedy, which could be seen as a foregone conclusion, because the chorus typically returns at the end of most verse–chorus works. However, the next analysis shows how the use of shifting chorus and terminal climax can alter an overall tragic narrative to be comedic, in which the contrasting narrative of the bridge supplants the negative, order-imposing hierarchy of the preceding verse–chorus units.

Three Close Readings of the USOP Series

The following three analyses show how the combination of lyrics, music, visuals, and borrowed material in DJ Earworm's mashups produce complex narratives that relay U.S. struggles in the given year. As in No More Gas, the complexity revolves around a negative order-imposing hierarchy (i.e., a negative status quo) and a positively charged transgression (i.e., an opposition to the status quo). Accordingly, the only possible narrative archetypes relate to the success or failure of the transgression. If the transgression is defeated, the work is a tragedy like No More Gas. If the transgression is successful, the work would be considered a comedy. Finally, the fate of the transgression could remain unresolved, resulting in an open-ended narrative (i.e., a cliffhanger), which will be seen in the last two works.

Each of these pieces will be explored through a top-down perspective that first identifies the major U.S. events of the year and then relates those themes to signifiers in the mashup. My interpretation will show how the piece requires a close reading of the combined lyrics, music, visuals, and borrowed material to overcome the consistently vague beginnings of each mashup's narrative and to illuminate how the complex narrative interactions of the order-imposing hierarchy and transgression relay contemporary struggles in U.S. society. The first two analyses take DJ Earworm's brief remarks on each work's narrative as a point of departure and then delve into greater depth on each work's meaning and the larger narrative conflicts at play. The last analysis reveals a complex, culturally relevant narrative in a USOP mashup with no commentary by DJ Earworm—as in the previous analysis of No More Gas.

Living the Fantasy

DJ Earworm refers to 2013's Living the Fantasy as a protest song against consumerism.Footnote 70 However, this message is difficult to perceive for many factors. First, DJ Earworm admits that this message was not incredibly clear and “didn't quite get there.”Footnote 71 Furthermore, there was no obvious anticonsumerism narrative that was prevalent in U.S. society at this point. This sentiment was far more pronounced in the Occupy Wall Street movement, which was at its height almost 2 years before this mashup. Finally, there were no noticeable anticonsumerism songs in 2013 that challenged economic inequality.

By closely examining the interaction of the lyrics, music, visuals, and the messages of borrowed works, I argue that this piece presents a more nuanced narrative of anticonsumerism than the Occupy Wall Street movement. Instead of insisting on economic justice, the song protests the consumerist idea that monetary riches will make one happy. This theme of embracing joy despite a lack of monetary riches reflects themes in many of 2013's Top-40 hits, such as Lorde's “Royals,” Avicii's “Wake Me Up,” and Macklemore's “Thrift Shop.” That is, this mashup may be capturing an unusually specific narrative in 2013's most popular songs about persevering through economic insecurity. In turn, the narratives of these works could be seen as an aftershock to the Occupy Wall Street movement, in which artists came to terms with economic inequality after that United States achieved no meaningful policy changes through the Occupy Wall Street movement.

As in No More Gas, the opening verse–chorus units do not clearly convey this theme of finding joy despite a lack of monetary riches. Instead, the introduction and opening verse–chorus units suggest some unnamed trouble that is met with an alternation of hope and despair. The dark tone of both units is signified by the sparse, minor-mode music and the visuals that feature either dark, isolated rooms or war-like landscapes. The lyrics of the first verse and its subsequent prechorus respectively describe a fall from grace and subsequent hope for a better future, which correlates with the narratives of Macklemore's “Can't Hold Us” and Avicii's “Wake Me Up” (Figure 11). The second verse takes a very different narrative path. It begins by reverting to the dark mood of the first verse; however, it is followed by a completely different prechorus that exchanges the earlier prechorus's narrative of rising hope with one of spiraling despair [1:48–2:00] (Table 2).

Figure 11. Relation of verse blended spaces on chorus blended space in Living the Fantasy.

Table 2. Formal Diagram of Living the Fantasy

This decline in narrative is reflected by musical differences between statements of each verse's subsequent chorus. As would be expected, each statement of the chorus shares the same melody and lyrics. Being featured at the beginning of each stanza of the chorus, the lyrics finally hint at the main narrative through Lorde's “Royals,” which describes eschewing gaudy wealth and finding power in a common, simple existence. The remaining lyrics proclaim to persevere, which is supported by DJ Earworm's explicit claim that Cyrus's “We Can't Stop” signifies resilience.Footnote 72 Reflecting the hope of the first verse–prechorus unit, the first chorus highlights enthusiasm through an energetic electronic dance music (EDM) accompaniment and visuals of partying (Figure 11). In contrast, the second chorus [2:02] reflects the resignation of the preceding verse–prechorus unit through static, sustained chords and images of apathy and anguish. Accordingly, the narrative of the initial chorus is undermined by the second chorus accompaniment's energy loss, which suggests waning endurance and highlights that finding power in a suppressed society may only be a fantasy.

The following B section is comprised of two distinct sections (bridge and breakdown) that serve as the major narrative pivot from despair back to hope. The bridge section signifies acts of escapism that continue the narrative decline of the previous verse–prechorus–chorus unit. The lyrics and images show two distinct acts of escapism: Physically driving away in a car and drug use. Although these acts are often portrayed positively in popular music, the dark imagery and static, sustained accompaniment highlight these as negative behaviors in the context of the mashup. This sense of complete resignation is captured by the ending lyrics of “in this torn up town, we're fine with this” and the associated ![]() $ \hbox{V}\,{{6 - 5}\atop {\vskip -2pt 4 - 3}} $ progression that suggests an impending perfect authentic cadence in C minor [2:51–3:00]. The deceptive resolution to an A-flat-major chord (VI in the key of C minor) initiates the second, abruptly hopeful breakdown section. The lyrics shift significantly to reflect an increased sense of importance and power, which correlates with brighter imagery and lyrics with a more affirmative message (Table 3).

$ \hbox{V}\,{{6 - 5}\atop {\vskip -2pt 4 - 3}} $ progression that suggests an impending perfect authentic cadence in C minor [2:51–3:00]. The deceptive resolution to an A-flat-major chord (VI in the key of C minor) initiates the second, abruptly hopeful breakdown section. The lyrics shift significantly to reflect an increased sense of importance and power, which correlates with brighter imagery and lyrics with a more affirmative message (Table 3).

Table 3. Relation of Verse Blended Spaces on Chorus Blended Space in Living the Fantasy

Changes in the accompaniment and lyrics suggest that the final chorus meets and exceeds the hopefulness of the original chorus (Figure 12). Instead of the static, sustained chords of the second chorus, this final chorus features the return of the energetic, EDM accompaniment of the initial chorus. In addition, it suggests a more enthusiastic sense of hope than the first chorus by omitting the original first stanza. Accordingly, the initial lyrics now focus on one of the most aggrandizing lines, “Let me be your ruler,” rather than the self-effacing lyrics of “And we'll never be royals” (see Table 2). Despite this omission, the final chorus is roughly twice the length of the original, which suggests a prolonged exclamation of hope that counters the tragic trajectory of the second, most recent chorus.Footnote 73

Figure 12. Relation of B-section blended spaces on chorus blended space in Living the Fantasy.

After an ostensible outro that is completely lifted from Pink's “Just Give Me a Reason,” the piece proceeds to a terminal climax that confirms the heroic ending of the narrative.Footnote 74 The visual and music fields feature a shift to high register signifiers through the imagery of tuxes and the use of trumpets,Footnote 75 which reflects a confidence found in the borrowed material from Timberlake's “Suit and Tie” and the sense of security in Capital Cities's “Safe and Sound.” The opening lyrics reflect this confidence by repeating the phrase, “Let me show you a few things.” Near the end of the terminal climax, however, the lyrics present a lack of monetary power through the repeated phrase, “Only got twenty dollars in my pocket.” This duality between self-assurance and poverty resonates with the message of the chorus: That one can find a sense of power and hopefulness despite a lack of wealth (i.e., not being royal).

Even though DJ Earworm directly commented on the meaning of the piece, my analysis illuminates his remarks and articulates the narrative struggle within the mashup. Although this piece was a protest song against consumerism, it was not immediately evident that the protest was against the idea that riches are required for happiness in a consumer-driven society. Furthermore, such a brief statement from the composer does not convey the narrative journey from the initial fall from grace, the rise of hope, the resignation in the bridge, and the final rise to a triumphant ending.

Into Pieces

DJ Earworm states that the main message of 2016's Into Pieces deals “With our fractured political climate, […] increased tension between police and Black Lives Matter and all sorts of things. We lost so many people that we loved this year.”Footnote 76 Both the 2016 presidential election and the Black Lives Matter movement relate to the division implied by the song's title. Most presidential elections engender increased partisan divisions and increased polarization, whereas Black Lives Matter is a movement that focuses on racial disparity, primarily between Black and white racial groups. Although the election clearly occurred in 2016, Black Lives Matter is a movement that was started in 2013 in the wake of the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the killing of Trayvon Martin. That being said, the Black Lives Matter movement was especially prominent in late 2016 with the highly publicized deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castillo, as well as the onset of Colin Kaepernick's NFL protest to kneel during the national anthem. The confluence of these events raises the question of whether the mashup speaks generally to both of these elements of division in U.S. society or if it highlights one over the other.

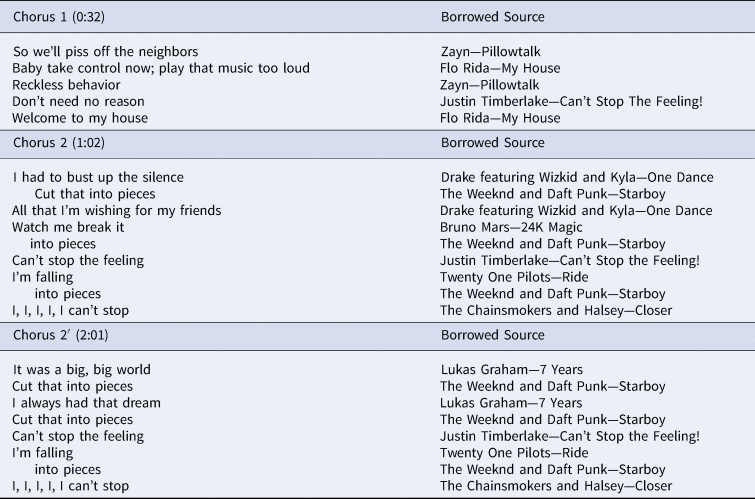

The clarity of the central message is muddled in this piece because the mashup has two distinct choruses, which feature different lyrics, melodies, and accompaniments (Table 4). Having different chorus sections is rare in popular music generally, but significantly more common in mashups. Yunek, Wadsworth, and Needle find that many of DJ Earworm's mashups have multiple chorus sections, such as the two contrasting chorus sections in “Toxic Death Day” by DJ Surge-n.Footnote 77

Table 4. Formal Diagram of Into Pieces

In this mashup, my interpretation of each section as a chorus is based on two primary factors: (i) They are sections that feature the same or similar melody and lyrics upon repetition and (ii) they are constructed from material from chorus sections. Similarly, chorus 1 [0:32] and chorus 2 [1:02] of Into Pieces are each repeated with the same basic melodic and lyrics, although, as my later analysis reveals, there are significant lyrical alterations that underscore shifts in the song's narrative trajectory. Chorus 1 features predominantly chorus material—with only one nonchorus excerpt—and the densest texture of the piece. Although the second chorus does not feature a high degree of chorus material, it features other chorus characteristics not found in chorus 1, such as the title lyrics and high internal text repetition.Footnote 78 In short, both sections fulfill the basic characteristics of a chorus, but it is difficult to assert that one chorus supersedes the other.

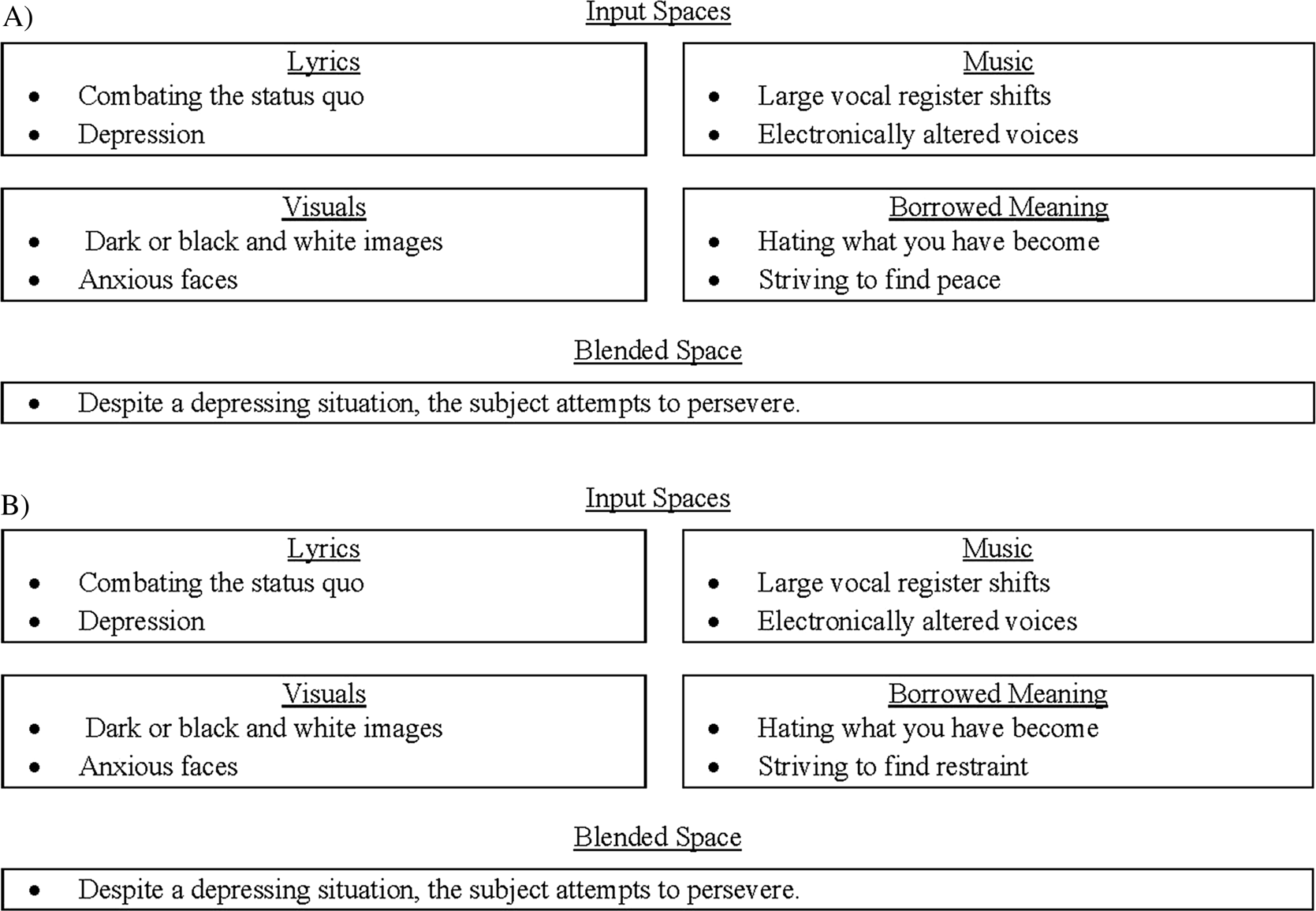

In addition to having two choruses, the central narrative is hard to ascertain because the two choruses elicit competing narratives. Looking at chorus 2 first, it conveys a dark atmosphere through images of anxious faces on dark or black-and-white backgrounds (Figure 13A). This anxiety maps onto the music's use of electronically distorted voices and frequent register shifts. The lyrics relay distress with the phrase, “Can't stop the feeling I'm falling into pieces,” which resonates with the narrative of hating what you've become from The Weeknd's “Starboy.” Alternatively, the lyrics also speak to an underlying drive to persevere by repeating the phrase, “I can't stop,” which reflects the narrative of twenty øne piløts's “Ride,” in which they constantly strive to find peace. In opposition, chorus 1 features bright party scenes with rising musical contours and natural or slickly polished vocals. Its lyrics convey coming together, which mirrors the party narrative of Flo Rida's “My House” (Figure 13B). Despite the festive atmosphere, the lyrics explicitly convey a more raucous party in which people are gathered for “reckless behavior.”

Figure 13. (A) Input and blended space for chorus 2 of Into Pieces. (B) Input and blended space for chorus 1 of Into Pieces.

In this isolated context, chorus 1 is a basic party song featuring a festive—albeit rambunctious—scene that stands in stark opposition to the dark atmosphere of chorus 2. As with the verses in No More Gas, I suggest the seemingly disparate narratives in this mashup complement one another to reveal a higher narrative in which interpersonal acts are prompted by intrapersonal struggle. I classify chorus 1 as interpersonal because of its use of “we” and the inference that the lyrics are directed at a third party through phrases such as “Welcome to my house” (Table 5). In contrast, chorus 2 is considered intrapersonal because of the use of “I” and “me” and the lack of an inferred third party. These inter-/intrapersonal narratives of choruses 1 and 2 are consistently continued by their following verses. The bright and interpersonal chorus 1 is followed by verse 2's festive greeting of “Welcome to my city,” whereas the dark and intrapersonal chorus 2 is followed by verse 3's helpless and introspective statement of “What can I say? That's the way it was.” More importantly, the lyrics leading into each of these choruses suggests a transition between intrapersonal and interpersonal perspectives. Chorus 1 is immediately preceded by the lyrics, “I think I'm losing my mind now. You shouldn't be fighting on your own,” which distinctly shifts from “I” to “you.” Conversely, chorus 2 is immediately preceded by “Your dreams are durations still holding on to something inside my bones,” which distinctly shifts from “your” to “my.”

Table 5. Lyrics for Chorus 1 and Chorus 2 and Chorus 2′ of Into Pieces

Taking a step back, the narrative that intrapersonal struggle fuels interpersonal action could apply to either the 2016 election or the Black Lives Matter movement. Political demonstrations and events are predicated on coming together to collectively address individual problems. Similarly, Black Lives Matter is associated with public gatherings to address a variety of issues impacting individuals in the Black community, such as police brutality. However, it is important to note that chorus 1's message of coming together and being reckless is more resonant with the Black Lives Matter movement than a prototypical political gathering because Black Lives Matter gatherings are disproportionately framed as chaotic and disruptive by the media.Footnote 79

I argue that the trajectory of the mashup reaches its most tragic point just before the bridge, based on the immediate placement of chorus 2 after chorus 1, significant shifts in the lyrics of chorus 2, and the pleading lyrics of the subsequent link section. Until this point, each chorus was followed by a section that extended its narrative. At this moment of the piece, however, chorus 1's brighter narrative is immediately followed by the dark narrative of chorus 2. This iteration of chorus 2 features significant changes to the lyrics that signal a deteriorating situation, in which the phrase, “I had to bust up the silence. Cut that into pieces.” from chorus 2 is replaced by, “It was a big, big world. Cut that into pieces.” in chorus 2′ (see Table 5). That is, instead of just disrupting the silent status quo, a previously united world is becoming fractured. This chorus is followed by a visually and lyrically dark link section that features repeated requests for divine intervention (Table 6).

Table 6. Lyrics for the Prebridge Link of Into Pieces

The bridge's visuals and lyrics further suggest that the overall narrative is more resonant with Black Lives Matter than political divisions, through depictions of prisons and references to police statements made in prominent Black deaths in 2016. The visuals are primarily set in a prison scene, which corresponds to a reference to “prisoners” in the opening line of the bridge's lyrics. Although incarceration occasionally impacts political groups, mass incarceration is a long-standing issue in the Black Lives Matter movement, which is resonant with the mashup's subsequent lyrics that suggest to “let them all loose.” The lyrics also contain the phrase, “Please don't make sudden moves,” which resonate with police statements made just prior to the 2016 shootings of Philando Castillo and Anton Sterling.

The ending of the piece reverses the preceding tragic trajectory through a reversal of the chorus sections and lyric alterations. Before the bridge, I suggested that the immediate placement of chorus 2 after chorus 1 could be read as cutting the festive mood short. In this case, the dark narrative of chorus 2 moves directly to the brighter, more inclusive narrative of chorus 1, which could be read as cutting the negative, dark thoughts short. Notably, the piece then ends with a truncated chorus 2 (functioning as an outro) that omits the negative lyrics that reference fracturing but retains the lyrics about persevering (Table 4). This message of “attaining joy despite a fractured social and political climate” is continued in the next work, which—as in the next mashup in the USOP series—could be seen as the reaction of the United States in 2017 to its internal divisions in 2016.

How We Do It

For the final example, I would like to explore a mashup that DJ Earworm never commented on: 2017's How We Do It. It would be difficult to capture the zeitgeist of 2017 in the United States without referencing Donald Trump's first year in office. Although his presidency may now be related to the Mueller report or the January 6th capitol insurrection, these events did not occur in 2017. Instead, mainstream media outlets associated his first year in office with a change in presidential norms and isolationist policies in the United States.Footnote 80 In terms of presidential norms, the media focused on the increased rhetoric of division between Trump and his Democratic detractors, his increased presence on TV and social media platforms, and the increase in false statements coming out of the White House, which can be seen as a continuation of the concept of alternative facts from the 2016 election. As part of Trump's “America First” policy, the media focused on how the president restricted access to the United States through an enhanced border wall with Mexico, a travel ban from predominantly Arab countries, and the curtailing of visas and immigration.

As in No More Gas, this mashup starts with a vague opening chorus whose few explicit signifiers seem at odds with the aforementioned zeitgeist of division and isolationism in 2017 (Table 7). The chorus continually repeats the phrase “This is how we do it,” which is one of the vaguest statements imaginable because of the exclusive use of generic verbs and pronouns without clear antecedents. This phrase is either followed by: (i) The nondescript phrase “all the time” or (ii) a series of locations. Along with the visuals, these lyrics feature a variety of locations both within and beyond the United States, including Puerto Rico, Uganda, Cuba, the United Arab Emirates, and France. Looking beyond the chorus, the visuals have two strong references to the Islamic countries that were impacted by the travel ban: (i) Cardi B's green kaftan in “Bodak Yellow” (filmed in Dubai) and (ii) the Arabic subtitles in Lil Uzi Vert's “XO TOUR Llif3.”Footnote 81 This implied theme of togetherness runs contrary to the climate of international and cultural division in 2017, especially with its references to Islamic and Spanish-speaking countries in the Americas. Accordingly, this chorus only makes sense if this message of togetherness is meant to transcend the atmosphere of division associated with Donald Trump's first year in office, which is precisely what my interpretation intends to show.Footnote 82

Table 7. Formal Diagram of How We Do It

In contrast to the chorus, verse 1 features a sudden shift to a darker tableau and sets up a series of diametric oppositions between a virtuous “me/I” and a malicious “you” that resonates with the prevailing zeitgeist of division. The opening line indicates a clear rift between the “me/I” and “you,” which is seen as negative because of the sudden shift of the bright, outdoor visuals of the chorus to the dark, interior settings of verse 1. The “you’” is interpreted as malicious because it is accused of hating, whereas the “me/I” is seen as virtuous because it rejects this division and attempts to transcend the hate of the “you” (Table 8). The second stanza begins with a delineation between fabrications and the truth. Accordingly, both of these divisions resonate with media accounts of Donald Trump increasing divisions along political, cultural, and international lines and reports that the frequency and degree of falsehoods increased under his presidency.Footnote 83

Table 8. Lyrics for Verses 1 and 2 in DJ Earworm's How We Do It

After a restatement of the chorus with its bright visuals of international locales, verse 2 returns to a dark aesthetic and references negative personality traits associated with President Trump in contemporary media accounts, such as lying, pride, and instability. The first stanza features two direct references to lying: (i) A direct accusation of the “you” lying and (ii) an inferred accusation of lying by telling the “you” to look the “me” in the eyes, with a reference to manipulation by the “you” being sandwiched in between. Throughout the section, there are repeated appeals to “be humble” and to “mask off,” which refer to the meaning of Future's song of the same name, in which Future articulates that he projects an image of strength and power while masking internal personal issues. Finally, the lyrics reference being erratic by saying, “I don't care if you go crazy.” All of these traits were associated with Trump at the time by mainstream media.Footnote 84 Accordingly, a large segment of the country was struggling with the direction of the country at this point, which was captured in multiple national polls.Footnote 85 This struggle is highlighted in the other sections of the song, such as the opening postchorus's lyrics “Seeing the beauty through the darkest days” and the prechorus's lyrics “It can be hard the way that things have been.”Footnote 86

Up to this point, the narrative features a major disconnect between the depressing verses and the effervescent chorus. Although avoiding division and negativity can be cast as positive traits, the dark visuals and tragic borrowed material portray the positive motivations of the “I/me” as part of a more taxing struggle that does little to explain the unequivocal joy of the chorus. Accordingly, the message of the chorus remains obscured, and its cheerfulness seems both incongruous and unearned.

As opposed to the previous works, I suggest that the optimistic message of the chorus is clarified by the alternative message presented in the bridge, signaling a message of hope for the future that is set in relief to the dark present portrayed in the verses.Footnote 87 The switch to the future is signaled explicitly in the lyrics, whereas the remaining images all show a sense of togetherness through large group shots (Table 9). The sense of international unity is shown both through the predominant use of visuals of Puerto Rico in “Despacito” and Uganda in French Montana's “Unforgettable.” In addition, the bilingual (English–Spanish) construction of the rap break's lyrics itself shows a sense of unity on a lyric level by melding two different languages together. This correlates with the message of the lyrics, which describes a slow process of coming together and inspiring faith in a unified future.

Table 9. Lyrics for Rap Break in DJ Earworm's How We Do It

*Translated Spanish lyrics in italics.

With the bridge in mind, the meaning of the chorus's refrain “This is how we do it” can now be fully interpreted. The vague “do it” can be interpreted as the coming together of the international community, which is expounded in the bridge. “This” can be seen as acting upon the virtues of avoiding division and transcending the hate contained in the verses. Together, my reading of the work suggests that the message is that the United States can overcome a perceived dark and isolationist present by transcending hate and coming together.Footnote 88 This message is reinforced in the outro's printed message “this is not the end,” which suggests that our dark present may lead to a brighter future (Figure 14).Footnote 89

Figure 14. Concluding text visuals in How We Do It.

It is interesting to note that this struggle between Trump-administration policies and calls for unity correlates with the harmonic ambivalence of the work's ubiquitous axis progression (vi–IV–I–V).Footnote 90 The specific progression is Bm–G–D–A, which I read as a B-minor tonic (vi) competing with the internal D-major tonic (I).Footnote 91 The B-minor tonic (vi) is asserted by being placed at the beginning of the progression, which is in competition with the G, A, and D (IV–V–I) chords that suggest D major as tonic.Footnote 92 If we associate this asserted B-minor tonic with the prevailing order and the D-major tonic with the transgression, we get a nice musical enactment of the overall narrative: The governmental policies of division in the Trump presidency are in opposition to the public outcry for unity.Footnote 93 By ending the piece on a V chord, the work underscores the final unresolved state of the narrative. Just as the final text line “This is not the end” suggests an unresolved narrative, so too does the piece remain harmonically unresolved through a terminal dominant chord (A major) that may finally resolve to a D-major tonic or yet again revert to B minor.

Conclusion

My interpretations suggest that DJ Earworm's mashups are complex works of high craftsmanship and depth that are distinct within the mashup genre for their original and culturally resonate narratives. As shown earlier, most mashups are dependent on the messages of the original tracks and add meaning by subverting, reinforcing, or altering the message through the introduction of new accompanimental material. This narrative dependence is related to these mashups’ musical construction, which typically retains large portions of the original lyric tracks, which are subsequently reinterpreted by the introduction of a different accompanimental track. DJ Earworm's mashups are distinctly different because they use such a variety of lyric and accompaniment fragments that isolating a preexisting message becomes difficult. Instead, these fragments coalesce into a new work with its own structure and message, which is natural given how the combination of fragments engenders new lyrics. In each case, my analyses showed how the signifiers in each work resonated with major U.S. cultural themes in their year of composition, which follows the stated compositional intent of the composer. These culturally significant themes explored complex struggles in U.S. society, such as fossil-fuel dependence, wealth inequality, political and racial divisions, and attempts to overcome those divisions.

The use of borrowed material not only highlighted the resonances between the contemporary musical landscape and U.S. society, but it also showed how these mashups allow for formal and narrative interactions that are distinctive to the mashup genre. The presence of melodically conflicting verses and choruses is uncommon in popular music because repetition creates greater coherence and memorability for the audience.Footnote 94 However, the use of borrowed material from Top-40 music allows for the presence of conflicting material without overwhelming the listener because (i) mashup enthusiasts have likely been exposed to the incorporated Top-40 hits and (ii) the formal roles of the material are already anchored by their source material.Footnote 95 The presence of conflicting formal units allows for greater narrative possibilities, such as contrasting the complementary ideas of low supply and high demand in the verses of No More Gas or intrapersonal struggle and interpersonal action in the choruses of Into Pieces.

As DJ Earworm states below, we are well past the popular peak of mashups in U.S. society. Although this genre is currently in popular decline, I hope that artists both within and beyond popular music will reengage with this artform. As my analyses of DJ Earworm's mashups have shown, they have distinctive storytelling potential and an ability to unearth widespread narrative trends within today's popular music. As of 2019, DJ Earworm states that his exploration of the medium will continue: “I know mashups were at a cultural peak right around the peak of the last decade. I know they're not as buzzworthy now. But I think they're a form that's here to stay and will be relevant.”Footnote 96

Competing Interest Statement

There are no competing financial or non-financial interests. I have no relationship with the composer being explored or the popular music industry at large. The only personal benefit is to my scholarly progression at my institution.

Jeffrey Scott Yunek is an associate professor of music theory at Kennesaw State University and former president of the South Central Society for Music Theory. He has presented at regional, national, and international conferences on Alexander Scriabin and DJ Earworm with related publications in Music Theory Spectrum, Music Analysis, and various book chapters.