1. Introduction

In early 2019, the SNC-Lavalin scandal shook the Trudeau government. SNC-Lavalin, a global engineering and construction company based in Montreal, was facing criminal charges for fraud and foreign bribery—the bribery of a public official of a foreign government to obtain a business advantage. In February 2019, the former attorney general Jody Wilson-Raybould testified to a House of Commons committee that she “experienced a consistent and sustained effort by many people within the government to seek to politically interfere in the exercise of prosecutorial discretion” in the SNC-Lavalin case (Wilson-Raybould, Reference Wilson-Raybould2019). According to Wilson-Raybould, the prime minister and his office pressured her to pursue a remediation agreement even though prosecutors in the case had decided that the criteria for a remediation agreement had not been met. Such an agreement would have allowed SNC-Lavalin to resolve the charges against it without a criminal trial or guilty plea if it agreed to certain penalties and conditions.Footnote 1

This article examines remediation agreements, a mechanism to resolve allegations of criminal wrongdoing by corporations. Remediation agreements are new to Canada, created in 2018 through an omnibus spending bill that amended the Criminal Code. This marked a notable change in how Canada addresses corporate crime, including foreign bribery. Canada's foreign bribery prohibition stems from commitments under international law and the 1999 ratification of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development's (OECD's) Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (hereafter referred to as “Anti-Bribery Convention” or “Convention”). For much of the Convention's existence, Canada relied exclusively on traditional criminal law tools—trials and plea bargains—to enforce its foreign bribery prohibition. These tools reflected how criminal law was typically applied to corporations in Canada. Before the 2018 reforms, if prosecutors pursued criminal charges against a corporation, the only outcome, short of a stay of proceedings, was a trial or plea bargain. With remediation agreements, Canada was pivoting and joining a growing list of countries that provide for corporate diversion—a mechanism that allows corporate criminal wrongdoing to be “diverted” away from traditional criminal justice processes. Corporations facing criminal charges in Canada now have another option: negotiating a remediation agreement and avoiding a trial or guilty plea by agreeing to certain penalties and conditions.

Why would Canada make such a change? One possible answer emerged with the SNC-Lavalin scandal. A National Post columnist argued that the law creating remediation agreements “was hand-crafted to deal specifically with the charges facing SNC-Lavalin” (Glavin, Reference Glavin2019). SNC-Lavalin is a large Canadian employer, a frequent contractor with the federal government and headquartered in the politically sensitive province of Quebec that can make or break federal governments. SNC-Lavalin lobbied for the introduction of remediation agreements (Dion, Reference Dion2019), and it is easy to see why they would be attractive to the company. If SNC-Lavalin obtained a remediation agreement, it could avoid the uncertainty of a protracted criminal trial and the consequences of criminal responsibility. If SNC-Lavalin was convicted at trial of foreign bribery or pleaded guilty to it, the company would be automatically suspended from bidding on federal government contracts—contracts that regularly value in the hundreds of millions of dollars and form a core portion of SNC-Lavalin's business (Seglins, Reference Seglins2015). A remediation agreement would also be an attractive outcome for the federal government, sparing it from years of prosecution and the potential inability to hire one of its principal contractors.

But this is, at best, only part of the story of what led Canada to introduce remediation agreements. With the 2018 reforms, Canada built a relatively strict regime for corporate diversion that set explicit legislative and judicial limits. This regime contrasts with the flexible regime of corporate diversion that the United States pioneered. It is surprising that Canada opted not to follow the US, where corporate diversion has been in place since the early 2000s and features regularly in US anti–foreign bribery enforcement. What's more, deviation from the US example was a consequential policy choice for Canada. It had the effect of narrowing SNC-Lavalin's chances of obtaining a remediation agreement and set the stage for the political scandal that followed.

To understand Canada's turn to corporate diversion and in the particular form of remediation agreements, I look beyond domestic determinants of policy change and explore the role of transnational lawmaking in the ongoing implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention. I argue that international monitoring of the Convention and criticism of Canada's lagging anti–foreign bribery enforcement pushed Canada to consider reforms and catalyzed a process of cross-national policy diffusion. Here Canada learned from other states. The US and UK provided lessons that corporate diversion could increase corporate criminal law enforcement, but learning from the UK was most consequential for the particular form of Canadian corporate diversion. Specifically, Canada drew from the UK's experience that a stricter form of corporate diversion could guard against criticisms of the practice—particularly concerns over transparency and public trust—and garner widespread support.

In making this argument, the article first locates Canada's adoption of corporate diversion alongside its international commitments to combat foreign bribery and in comparison to corporate diversion in the US. Section 3 considers growing scholarship on comparative international law and transnational lawmaking and argues that the implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention is an ongoing process that is shaped by international monitoring and cross-national policy diffusion. Section 4 turns to the evidence of transnational lawmaking in producing remediation agreements and a qualitative historical analysis (Thies, Reference Thies2002) of a range of primary source documents. As is described further in the appendix, this methodology entails an analysis of OECD monitoring reports, non-governmental organization (NGO) reports, and records of the policy-making process in Canada, including public submissions to consultations on corporate diversion held by the federal government in 2017. The law that created remediation agreements is a few pages in a 500-page plus omnibus budget bill that received little independent parliamentary debate or examination. Thus, the public consultations offer some of the best evidence of how the government created remediation agreements and showcase the importance of transnational sources of legal change in this process.

This research improves our understanding of an important policy change in Canada, identifying multiple pressures for reform that go well beyond the SNC-Lavalin case. It adds to growing research on transnational lawmaking, showing how transnational influences produced national legal change, and suggests promising avenues for future research in investigating the diffusion of corporate diversion more broadly, including to countries such as Australia and Ireland that are contemplating such reforms. Further, this study has policy implications for international anti–foreign bribery law, pointing to an emerging national divide in the form of corporate diversion.

2. International Anti–Foreign Bribery Law and Corporate Diversion

Understanding Canada's introduction of corporate diversion requires consideration of one of its newest crimes targeting business activity: the prohibition against foreign bribery. Canada's anti–foreign bribery law stems from international law, principally the OECD Convention, which entered into force in 1999.Footnote 2 The Convention's core provision is Article 1, which obligates states to criminally prohibit foreign bribery (Rose, Reference Rose2015: 66). The Convention requires that states ensure that legal persons, such as corporations, are subject to liability for foreign bribery (Article 2) and that states punish foreign bribery through “effective, proportionate and dissuasive criminal penalties” (Article 3). Article 5 of the Convention instructs that state investigations and prosecutions of foreign bribery cases “shall not be influenced by considerations of national economic interest, the potential effect upon relations with another State or the identity of the natural or legal persons involved.” Beyond these provisions, the Convention does not explicitly address how states should enforce their anti–foreign bribery laws and does not mention corporate diversion.

Canada, like the large majority of the other Convention states, quickly complied with its Article 1 obligation (OECD, 1999). Canada's Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act (CFPOA) became law in 1999 and created a criminal offence of foreign bribery. Countries varied widely in how frequently they enforced their new anti–foreign bribery laws. Seventeen OECD Convention states have yet to complete a single enforcement action, while the US, the leading enforcer of anti–foreign bribery laws, regularly completes dozens of cases a year (OECD, 2020). Furthermore, countries applied their new anti–foreign bribery laws in markedly different ways (Acorn, Reference Acorn2018). Some countries, like Canada, relied exclusively on traditional criminal law tools and criminal investigations and prosecutions. Other countries made use of a wide range of enforcement tools, including corporate diversion. As I discuss below, the use of corporate diversion in anti–foreign bribery enforcement first emerged in the US and has since been adopted by other OECD Convention countries, including the UK, France and, as of 2018, Canada (OECD, 2019).

a) The US's flexible regime of corporate diversion

The US was the first country to prohibit foreign bribery with its Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) of 1977 and championed the creation of the OECD Convention (Abbott and Snidal, Reference Abbott and Snidal2002; Gutterman, Reference Gutterman2015). Corporate diversion—what the US calls deferred prosecution agreements (DPAs) and non-prosecution agreements (NPAs)—are central to US foreign bribery enforcement. In a DPA, charges against a coporation are “deferred” and not prosecuted if a corporation agrees to certain penalties and conditions; in an NPA, prosecutors refrain from bringing charges in the first place if the corporation agrees to the prosecutors' terms. Looking at the period from 2004 to 2014, Mike Koehler reports that 85 per cent of corporate foreign bribery enforcement actions by the US Department of Justice (DOJ) involved corporate diversion (Koehler, Reference Koehler2015: 521).

Corporate diversion in the US is a flexible tool, controlled by prosecutors and governed by DOJ policy. The DOJ began using DPAs and NPAs in the early 2000s after the indictment and conviction of the former Big Five accounting firm Arthur Andersen led to the loss of thousands of jobs at the firm (Ashcroft and Ratcliffe, Reference Ashcroft and Ratcliffe2012: 31–33). Then attorney general John Ashcroft, writing with former US attorney John Ratcliffe, explains that after Arthur Andersen, the DOJ began to see DPAs and NPAs as promising enforcement mechanisms that could avoid the “collateral consequences of corporate prosecutions” and provide “an effective means of mandating improved corporate governance and, in so doing, restor[e] confidence in the market-place without destroying the corporations and jobs that provide a market in the first place” (Ashcroft and Ratcliffe, Reference Ashcroft and Ratcliffe2012: 31–32). Successive memoranda within the DOJ and revisions to the Justice Manual, the policy document guiding US federal prosecutors, have since established DPAs and NPAs as “an important middle ground between declining prosecution and obtaining the conviction of a corporation” (section 9-28.200).

It is perhaps unsurprising that corporate diversion, as a creature of DOJ policy, empowers federal prosecutors. It is decisions of prosecutors that determine whether a DPA or an NPA will be pursued with a given corporation and with what terms; courts have little authority to review these agreements (Arlen, Reference Arlen2016; Davis, Reference Davis, Rose-Ackerman and Lagunes2015: 302; Garrett, Reference Garrett2014: 149). The Justice Manual specifies factors that prosecutors “should consider” in deciding whether to negotiate a DPA or an NPA, including “the nature and seriousness of the offense,” “the corporation's history of similar misconduct” and the “collateral consequences” of a prosecution, such as the “harm to shareholders, pension holders, employees” (section 9-28.300). Still, prosecutors “have complete discretion” in deciding whether to pursue corporate diversion, including “which factors to emphasize and also what factors to consider beyond the ten listed in the [Justice Manual]” (Arlen, Reference Arlen2017: 6; see also, Brewster and Buell, Reference Brewster and Buell2017: 207).

It is easy to see why DPAs and NPAs have become a favoured tool of US prosecutors for responding to allegations of foreign bribery by corporations. The prospect of a DPA or an NPA can encourage voluntary disclosures by corporations and cooperation with authorities and can speed up and simplify enforcement actions, reducing the resource burden on the state of a full-scale prosecution against a well-resourced corporation for a cross-border crime such as foreign bribery (Spahn, Reference Spahn2012: 14–15). Further, while corporate diversion avoids a determination of criminal responsibility, DPAs and NPAs can impose significant fines on corporations and often require improvements to corporate policy—for instance, to strengthen training and anti-bribery compliance programs (Alexander and Cohen, Reference Alexander and Cohen2015). Prosecutors can also gain access to information otherwise held only by the company, potentially spurring prosecutions against individuals involved in the crime (Arlen, Reference Arlen, Søreide and Makinwa2020: 162–63).

But there are also concerns with American corporate diversion. Some have questioned whether US prosecutors’ broad discretion over corporate diversion conforms to rule of law principles (Arlen, Reference Arlen2016) and whether the widespread use of the practice fuels a “too big to jail” culture, where the most important American companies escape accountability for their crimes (Garrett, Reference Garrett2014). In particular, the lack of “meaningful judicial scrutiny” in the US use of corporate diversion has raised alarm (Koehler, Reference Koehler2015: 505; Arlen, Reference Arlen2016; Garrett, Reference Garrett2014). There are also questions as to whether the US practice allows factors that Article 5 of the OECD Convention deems impermissible, such as the national economic interest, to influence decision making (OECD, 2010: 21).

b) Canada's strict regime of corporate diversion

When Canada adopted corporate diversion, it did so with significant distinctions from the US and established a stricter regime with remediation agreements. One important difference was that the Canadian government created remediation agreements with legislation that amended the Criminal Code, whereas in the US, corporate diversion remains solely a prosecutorial policy. Further, while Canadian law identifies similar broad aims for corporate diversion—including avoiding collateral consequences (section 715.31(f))—Canada's Criminal Code establishes a detailed framework to govern the use of remediation agreements. US prosecutors can consider factors such as the gravity of the offence and the corporation's history of wrongdoing in deciding whether to pursue a DPA or an NPA; but in Canada, the Criminal Code states that prosecutors “must consider” these and other factors before negotiating a remediation agreement (section 715.32(2)). The Criminal Code also identifies factors that a prosecutor “must not consider.” If the corporation is suspected of foreign bribery, “the prosecutor must not consider the national economic interests, the potential effect on relations with a state other than Canada or the identity of the organization or individual involved” (section 715.32(3)). These provisions echo Article 5 of the OECD Convention. The US Justice Manual provides no similar restriction.

If the threshold is met to negotiate a remediation agreement, the Criminal Code imposes additional requirements before a remediation agreement takes force. The Criminal Code specifies mandatory contents of a remediation agreement (section 715.34(1)) and requires that the prosecutor apply to a court for approval of the remediation agreement (section 715.37(1)). The court must assess whether the remediation agreement is “in the public interest” and its terms are “fair, reasonable and proportionate to the gravity of the offence” (section 715.37(6)).

The adoption of this stricter regime for corporate diversion is something that we would not expect if Canada was simply importing an American legal innovation, as scholarship on the “globalization of American law” might suggest (Keleman and Sibbitt, Reference Keleman and Sibbitt2004) and to which existing research suggests Canada may be particularly susceptible (for example, Campbell and O'Carroll, Reference Campbell and O'Carroll2009; Schneiderman, Reference Schneiderman2015). Nor is a strict regime of corporate diversion something we would expect if the Canadian government created remediation agreements simply to protect national champions, such as SNC-Lavalin, and further its national economic interest, as more realist theories of international law would predict (Goldsmith and Posner, Reference Goldsmith and Posner2006). Adopting a US-style of corporate diversion would have maximized the discretion of Canadian prosecutors. Instead, by establishing legislative and judicial requirements for corporate diversion, Canada reduced the chances of a particular corporation obtaining a remediation agreement. As we saw in the SNC-Lavalin case, prosecutors were bound by the Criminal Code in deciding whether to pursue a remediation agreement. The prosecutor in the case stated that the required Criminal Code factors—particularly the gravity of the harm and the company's record of similar offences—did not support the negotiation of a remediation agreement with SNC-Lavalin (Fife, Reference Fife2020). In addition, SNC-Lavalin was charged with foreign bribery, meaning that prosecutors were further restricted by what they could not consider, including the identity of the defendant or the national economic impact of criminal prosecution.

3. The Transnational Sources of Legal Change

As discussed above, it was the OECD's Anti-Bribery Convention that led Canada to originally prohibit foreign bribery. I argue here that the OECD Convention has continued to influence Canadian law through an ongoing process of implementation and transnational lawmaking.

In developing this argument, I draw on growing bodies of scholarship that recognize a range of national responses to international law. The research agenda of comparative international law seeks to identify and explain how and why states engage with international law in distinct ways (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Stephan, Verdier and Versteeg2015). Scholars of transnational legal process see “transnational law”Footnote 3 as “constructed, carried and conveyed” and anticipate that its impact on states will be “differentiated” (Sassen, Reference Sassen2006: 34; Shaffer, Reference Shaffer2012: 237). Scholars in international relations similarly recognize that international norms can be localized in their application by particular states (for example, Acharya, Reference Acharya2004). Together, these scholars problematize a unidirectional “download” of international law (Shaffer, Reference Shaffer2012: 235) or “internalization” of international norms (Goodman and Jinks, Reference Goodman and Jinks2008).

In challenging the notion of a singular and concordant reception of international law, this scholarship directs us to consider how the meaning and the application of international law is produced and altered over time and identifies two important pathways of change that are of relevance here. First, this scholarship points to exchange between national and international legal orders as a site of potential adaptation. Here we can see the implementation of international law as a “multidirectional, diachronic process” (Shaffer, Reference Shaffer2012: 238), which can not only produce distinct national responses to international law but also a “recursive” process where national applications “feed back” into transnational lawmaking (Shaffer, Reference Shaffer2012:, 238; Halliday and Carruthers, Reference Halliday and Carruthers2007; Ivory, Reference Ivory, Shaffer and Aaronson2020). Second, Terence Halliday and Bruce Carruthers make clear in their account of “lawmaking in a global context” that this process is not exclusively vertical between the local and the transnational; instead, we can also expect adaptations in the implementation of international law arising from exchanges across national levels (Halliday and Carruthers, Reference Halliday and Carruthers2007, Reference Halliday and Carruthers2009). As scholarship on policy diffusion has shown, policy choices in one state can be “systematically conditioned by prior policy choices made in other countries” (Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2007: 7). Similarly, we may well expect that the choices available to one state implementing its international obligations—or revisiting its implementation—can be decisively weighted by the implementation decisions of other states.

Consideration of this scholarship highlights the transnational pathways that have worked together to produce national changes in the implementation of international anti–foreign bribery law. More specifically, as I explore below, a recursive process of international monitoring and cross-national policy diffusion can alter how states enforce their national anti–foreign bribery prohibitions.

a) International monitoring and policy diffusion of anti–foreign bribery law

In the more than two decades of the Anti-Bribery Convention's operation, the OECD has actively monitored its implementation through successive “rounds” of country reviews. Those familiar with the OECD's monitoring role describe it as “peer pressure” (Bonucci, Reference Bonucci, Pieth, Low and Bonucci2013: 538; Rose, Reference Rose2015: 61) or what scholarship on state socialization calls “naming and shaming” (Carraro et al., Reference Carraro, Conzelmann and Jongen2019). Early OECD monitoring was concerned with national legislation and prohibitions of foreign bribery but adopted a “new focus on enforcement” in the 2010s and third round of country reviews (Bonucci, Reference Bonucci, Pieth, Low and Bonucci2013: 541). The chair of the OECD Working Group on Bribery in International Business Transactions noted that the fourth round of country reviews, started in 2016, could be aptly titled “enforcement, enforcement, enforcement” (Rugman, Reference Rugman2016). Since 2008, the OECD has published data on national anti–foreign bribery enforcement. This data, combined with the country reviews, provide information and measures of state performance that other actors can deploy as “tacit social pressure” on states that do not meet expectations (Kelley, Reference Kelley2017; Kelley and Simmons, Reference Kelley and Simmons2015). What this has meant recently is that states that failed to demonstrate significant enforcement could expect concerted pressue by the OECD and other states to improve.

While the OECD has clearly stated the importance of anti–foreign bribery enforcement, it has stopped short of providing a definitive policy prescription for how states should do this. The organization has called for further study of corporate diversion (OECD, 2016), but it has not taken an official position on the practice, nor has it set out clear standards for its use (Ivory and Søreide, Reference Ivory and Søreide2020). This may be a result of what Kevin Davis has described as the OECD's “every-little-bit-helps approach”—anything that states “can do to help combat transnational bribery is likely to be worthwhile” (Davis, Reference Davis2019: 5). Of course, not all enforcement efforts are equal, and we should be careful to not equate increasing enforcement frequencies with increasing effectiveness of international anti–foreign bribery law. However, given that “under-enforcement has become the state of affairs” (Brewster and Dryden, Reference Brewster and Dryden2018: 239), the OECD often focuses simply on increasing national enforcement efforts.

Still, the fact that some OECD states, notably the US and more recently the UK, have used corporate diversion in anti–foreign bribery enforcement is significant for other OECD Convention states. As policy diffusion expects, once some states began to use corporate diversion, this influences the policy choices available to other states, particularly those reconsidering their implementation of the Convention and the enforcement of their anti–foreign bribery prohibitions. Scholars of policy diffusion typically identify four mechanism that spread policies across countries: coercion, learning, competition and emulation (Marsh and Sharman, Reference Marsh and Sharman2009; Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2007). Coercion is least likely to be at play among OECD states, which are the world's wealthiest and do not exhibit the extreme imbalances that can make countries susceptible to coercion (Lee and Strang, Reference Lee, Strang, Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2007: 149). In emulation, it is the status of a particular policy and whether the policy has become “socially accepted” that propels its adoption by multiple states (Marsh and Sharman, Reference Marsh and Sharman2009: 272; Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2007: 34). However, there has been no overt international sanctioning of corporate diversion as the socially acceptable means to enforce anti–foreign bribery law, and significant variation persists in how states apply this practice (OECD, 2019: 17, 141–51).

Competition has likely increased pressure on states that lack corporate diversion. Through competition, a policy innovation in one state can alter the payoffs for a similar reform in other states (Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett2007: 22). Specifically, more business-friendly policies adopted in one country can lead others to adopt similar policies to ensure that their businesses and investors are not tempted to relocate. Corporate diversion can be seen as a more business-friendly law reform. It can offer reduced sanctions for wrongdoing as well as certainty and timeliness—avoiding a drawn-out criminal prosecution and possible finding of criminal guilt and collateral consequences, which businesses may well find attractive.

Learning also appears likely in the spread of corporate diversion, particularly when considered alongside the active monitoring of the Anti-Bribery Convention. Learning is “a ‘rational’ decision’ by governments” to follow “foreign institutions and practices to the extent that these measures produce more efficient and effective policy outcomes” (Marsh and Sharman, Reference Marsh and Sharman2009: 271). Through learning, states can also glean information about public reactions to a policy (Graham et al., Reference Graham, Shipan and Volden2013: 691). For all but the US, the OECD Convention required the introduction of a brand-new offence of foreign bribery. It is perhaps to be expected that states that negotiated and agreed to the Convention would look to each other in implementing this shared obligation. Further, as some states faced international pressure to increase the anti–foreign bribery enforcement, it is similarly not surprising that they would consider how others—particularly those like the US that are leading enforcers—had implemented the Convention.

What's more, the OECD monitoring process itself can facilitate learning, and particularly for states that have come under fire for their anti–foreign bribery enforcement records. Research by Hortense Jongen shows that the OECD's country review process enables policy learning, as delegates report learning from the evaluations of other countries (Jongen, Reference Jongen2018: 923). A review of all OECD country monitoring reports by Tina Søreide and Radha Ivory finds that the OECD “implicitly endorse[s] domestic settlement laws and practices,” including corporate diversion, “as mechanisms that contribute to the enforcement of domestic anticorruption laws” (Ivory and Søreide, Reference Ivory and Søreide2020: 25). A recent OECD report finds that the majority of foreign bribery cases have been resolved outside of a criminal trial, which frequently includes corporate diversion (OECD, 2019). Thus, even though the OECD has stopped short of explicitly recommending corporate diversion at large, it may nonetheless be performing what Ezequiel Gonzalez-Ocantos (Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos2018) describes as “communicative entrepreneurship,” which has led states to the practice. As a communicative entrepreneur, the OECD is not overtly teaching states a specific behaviour but instead is encouraging states to revisit particular actions—here the national enforcement of anti–foreign bribery law—and facilitating discussions among them for reform (Gonzalez-Ocantos, Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos2018: 740).

It is not only the OECD that participates in international monitoring of international anti–foreign bribery law. Anti-corruption NGOs, such as Transparency International (TI), were instrumental in the creation of the OECD Convention (Abbott and Snidal, Reference Abbott and Snidal2002) and continue to be important actors in the area (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Sharman, Reference Eilstrup-Sangiovanni and Sharman2019). TI produces its own monitoring reports on anti–foreign bribery enforcement (see, for example, Transparency International, 2018). Further, international anti-corruption NGOs, including TI, Corruption Watch and Global Witness, have advanced standards for corporate diversion and also monitor national practices. Here the core NGO message is that states should use corporate diversion judiciously and in appropriate circumstances, not as a default response to foreign bribery. NGOs recommend that corporate diversion be established in a legislative regime, with clear criteria on how and when it will be used, and subject to judicial oversight (Corruption Watch et al., 2016). Legislation should explicitly forbid “Article 5 considerations,” such as the national economic interest, from influencing the use of corporate diversion (Corruption Watch et al., 2016). In short, these anti-corruption NGOs also form part of the international monitoring and transnational lawmaking that can fuel national-level change in the implementation of international anti–foreign bribery law.

4. Transnational Lawmaking in Canada's Turn to Corporate Diversion

The article turns now to the evidence of transnational lawmaking in the introduction of remediation agreements. It looks first to international monitoring of Canada's implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention and increasing pressure on Canada to improve enforcement. This section looks next at the salient case of the UK and its introduction of corporate diversion in the early 2010s. While other OECD Convention countries, such as France,Footnote 4 have also adopted corporate diversion, the UK's experience was particularly relevant, given legal similarities between Canada and the UK and the UK's success in addressing international criticism of its anti–foreign bribery enforcement. The UK, like Canada, had initially implemented its anti–foreign bribery laws with traditional criminal law enforcement. After strong international criticism of its lagging enforcement record in the early 2000s, the UK began experimenting with alternative enforcement tools and ultimately produced a stricter form of corporate diversion than the US had pioneered. The final portion of this section provides evidence of Canada's policy learning, particularly from the UK on the advantages of a strict form of corporate diversion, by reviewing Canada's policy-making process for remediation agreements.

a) Increasing international criticism

The OECD's first review of Canada's implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention was generally positive, declaring that Canada's anti–foreign bribery law, the CFPOA, met the Convention's requirements (OECD, 1999: 23). By 2011, however, the OECD's assessment had shifted dramatically. An OECD press release summed it up: “Canada's Enforcement of the Foreign Bribery Offence Still Lagging; Must Urgently Boost Efforts to Prosecute” (OECD, 2011b). As the OECD reported, Canada had completed only one foreign bribery enforcement action in over a decade (R. v. Watts, 2005), despite substantial risks of foreign bribery to Canadian business and their leading role in the global extractive industry and operation in countries where bribe solicitation is common (OECD, 2011a: 8).

In response to the OECD's criticism, the Harper government amended the CFPOA in 2013. The member of Parliament who presented the bill stated that “this legislation arose out of some criticisms that were made about the current Canadian legislation by the OECD” (Dechert, Reference Dechert2013). The CFPOA amendments largely reinforced the reliance on traditional criminal law tools in foreign bribery enforcementFootnote 5 and did not generate substantial increases. By 2019, Canada's tally of completed anti–foreign bribery enforcement actions was still in the single digits (OECD, 2020).

The determinants of enforcement for a transnational crime such as foreign bribery are complex (Brewster, Reference Brewster2014; Brewster and Buell, Reference Brewster and Buell2017), and there is a powerful argument that short-term economic interests and a lack of political will have impeded enforcement efforts across OECD states (Spahn, Reference Spahn2012: 14; Brewster, Reference Brewster2014: 95). Even so, Canada, with its reliance on traditional criminal law tools, faced a particularly challenging task in demonstrating improvements to its enforcement record. As TI noted in its 2013 annual enforcement report, “The CFPOA currently requires full-blown criminal investigations and prosecutions, which entail substantial costs” (Transparency International, 2013: 79). The cross-border and complex nature of foreign bribery makes traditional criminal law enforcement particularly challenging, as prosecutors must gather evidence across multiple jurisdictions to meet the high standard of criminal guilt. One of Canada's most well-known foreign bribery cases, the prosecution of Nazir Karigar, provides a telling example. Karigar self-reported his attempted bribery of an Indian public officials to authorities, but it took seven years before he was finally tried, convicted and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment.

In sum, following the OECD's critical review in 2011, Canada struggled to show noticeable improvements in foreign bribery enforcement. The OECD's fourth round of reviews started in 2016 and will entail further scrutiny of Canadian enforcement. The OECD has not specifically recommended that Canada adopt corporate diversion, but it is easy to see how Canadian policy makers would have begun to consider such a policy change—particularly given the recent experience of the UK.

b) The UK's innovation of strict corporate diversion

International criticism of the UK's implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention came earlier than for Canada. The UK had yet to complete a single foreign bribery case when, in 2006, prosecutors publicly ended an investigation of the defence company BAE Systems, despite allegations by former employees that the company was bribing Saudi officials (Williams, Reference Williams2008: 202). The OECD sharply criticized the UK, raising concerns that the decision not to prosecute violated Article 5 of the Anti-Bribery Convention (OECD, 2008). The OECD conducted an additional review of the UK and warned that the country's failure to improve could “potentially trigger the need for increased due diligence over UK companies by their commercial partners or Multilateral Development Banks” (OECD, 2008: 4).

The OECD's criticism led the government to reform its anti–foreign bribery law with the 2010 Bribery Act and also led to experimentation by prosecutors with alternative enforcement tools. As in Canada, the government initially used only traditional criminal investigations and prosecutions to enforce its anti–foreign bribery laws, which made for challenging and slow-moving enforcement. In 2009, the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), the principal agency tasked with prosecuting foreign bribery crimes, announced a new policy to use civil recovery orders (CROs) for foreign bribery involving corporations (SFO, 2009). Through a CRO, an offending corporation would disgorge—pay to the state—proceeds obtained from foreign bribery but would not face criminal prosecution or sanction. The SFO was explicit that it borrowed from the US in developing this new policy. The SFO director at the time stated: “I have learned a lot from the US system here” (SFO, 2008). CROs, he explained, would help to avoid the “protracted investigations lasting several years and costing millions of pounds” that traditional criminal law enforcement required (SFO, 2008).

CROs generated enforcement of anti–foreign bribery laws,Footnote 6 but they also generated criticism. A British judge questioned the use of CROs in foreign bribery cases, given “the serious criminality of … companies, who engage in the corruption of foreign governments” (R. v. Innospec, 2010: para. 38). The UK TI chapter warned of over-reliance on CROs and potential for the “inappropriate use of prosecutorial discretion” given that prosecutors alone determine when a CRO is used (Transparency International UK, 2012). The OECD too raised concerns about the dearth of transparency and accountability with CROs, warning that their use “fails to instil public and judicial confidence” (OECD, 2012: 24).

With continued international pressure to increase anti–foreign bribery enforcement and mounting criticism of CROs, the UK turned to a new enforcement tool in 2012, the UK DPA. As in the US, UK DPAs allow corporations suspected of foreign bribery and other crimes to avoid a criminal prosecution if they agree to certain conditions. But there are important distinctions in the British DPA. The government developed DPAs in response to criticisms of CROs (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Hawley, King, Søreide and Makinwa2020) and created a stricter form of corporate diversion. British DPAs are governed by legislation: the Crime and Courts Act, which requires judicial supervision and approval that a DPA “is in the interests of justice” and is “fair, reasonable and proportionate.” The act requires prosecutors to publish a code on DPAs, which sets out the mandatory contents of DPAs and provides guidance on when they should be used. For instance, the code states that a history of similar misconduct and harm caused by the wrongdoing would weigh against the use of a DPA. The code instructs prosecutors to consider the “collateral effects” of a prosecution but rules out considerations of the national economic interest or other impermissible consideration under Article 5 of the OECD Convention for foreign bribery cases.

Since DPAs became available, they have become common in British foreign bribery enforcement and have received a much warmer reception than CROs. The OECD praised the government in its fourth review in 2017, noting that it had “taken significant steps since Phase 3 to increase enforcement of the foreign bribery offence” (OECD, 2017). TI now regularly lists the UK as an “active enforcer” of anti–foreign bribery laws (Transparency International, 2018).

Still, the British rollout of DPAs has not been free of criticism. One of the most prominent UK DPAs is the 2017 Rolls-Royce agreement, where the company paid a £497 million fine to British authorities to resolve foreign bribery charges (SFO, 2017). The judge in the case described Rolls-Royce's conduct as “egregious criminality over decades” but nonetheless approved the DPA (SFO v. Rolls-Royce plc, 2017). Concerns about the collateral consequences of a criminal prosecution of Rolls-Royce, including its suspension from government contracts, were cited to justify this outcome. However, Corruption Watch argued that the collateral consequences were “over-stated” and questioned what the Rolls-Royce DPA says about the “willingness and ability” of prosecutors to purse a prosecution of foreign bribery against an important national company (Corruption Watch, Reference Watch2017).

c) Analyzing Canada's policy choice of remediation agreements

This section turns to the immediate policy-making process in Canada that created remediation agreements and provides evidence of transnational lawmaking. The policy record shows pressure for reform generated by international monitoring and indicates learning not only that corporate diversion could increase the enforcement of anti–foreign bribery and other criminal laws in Canada but also that the UK's version of the practice could help mitigate criticisms and ensure a broad coalition of support.

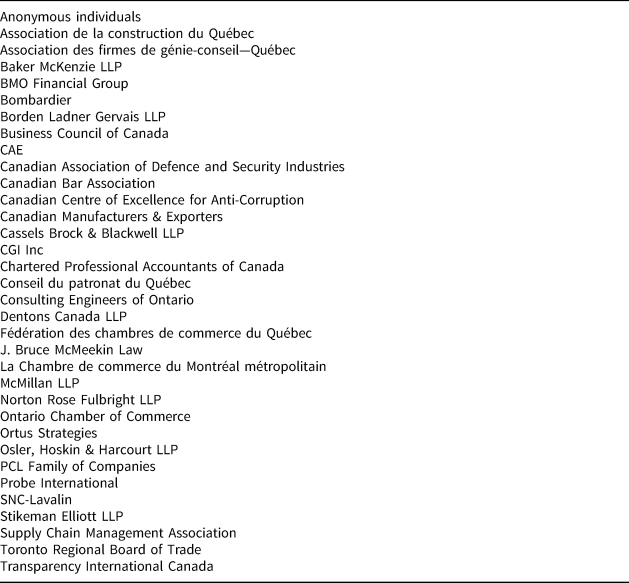

This section draws largely on documents from the 2017 public consultations on corporate diversion. Specifically, I analyzed documents produced by the federal government relating to the consultation, as well as written submissions to the consultations that I obtained pursuant to an Access to Information Act request. I reviewed 42 written submissions to the consultations, which included 20 submissions from businesses and business associations, 9 submissions from law firms, 1 submission from the Canadian Bar Association (CBA), 3 submissions from NGOs and 9 submissions from individuals. I reviewed the documents in their entirety, focusing particularly on the rationale for corporate diversion and on the form and nature of the practice that Canada should adopt.

The first thing that jumps out from the public consultations is widespread support for corporate diversion. The large majority of the submissions, 36 out of 42, supported the introduction of the practice; only 4 submissions opposed it, and 2 submissions did not state a firm position. Notably, support for corporate diversion came from all groups: businesses, law firms, NGOs and individuals.

Many of the submission that favoured corporate diversion did so on the ground that it would increase enforcement of corporate crime, particularly for complex crimes such as foreign bribery. As the law firm Dentons wrote in its submission: “The introduction of DPAs may reasonably be expected to result in a tangible increase in the number of enforcements actions, not only because Canada's limited investigative resources would be less stretched, but also because a DPA regime should encourage fulsome co-operation with government investigations.”Footnote 7 In addition to Dentons, 17 other submissions included similar statements that corporate diversion could be expected to increase the detection and enforcement of corporate crime. Ten more submissions noted that corporate diversion would be likely to increase voluntary disclosure of wrongdoing by corporations and/or cooperation with authorities—which could also be expected to increase enforcement.

Some of the participants in the consultation explicitly connected corporate diversion to improving Canada's lagging anti–foreign bribery enforcement record, suggesting that it could alleviate some of the international pressure on Canada. The Canadian Centre of Excellence for Anti-Corruption (CCEAC) argued that the introduction of corporate diversion could help Canada overcome a “visibility deficit in terms of prosecution and deterrence” of anti–foreign bribery law. TI Canada stated that DPAs “have the potential to support increased enforcement of anti-corruption laws” for a country such as Canada that struggles with low enforcement. Dentons and the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) similarly noted the heightened international scrutiny of Canada's enforcement record for corporate crime, which they argued corporate diversion could help address. In a Senate hearing after the public consultations, Marco Mendicino, the parliamentary secretary to the minister of justice and attorney general, also pointed to the OECD and TI in supporting the introduction of corporate diversion in Canada (Mendicino, Reference Mendicino2018).

Further, the submissions indicate that participants were learning from the American and British experience. Thirteen of the submissions pointed to the US and the UK in support of their arguments that corporate diversion would increase self-reporting by corporations and the enforcement of corporate crime. For example, TI Canada based its recommendation of the introduction of corporate diversion in Canada on its review of the practice in the US and the UK, and the Dentons, CPA and CCEAC submissions also drew on the US and UK as successful examples of incentivizing corporate self-reporting and increasing enforcement. The CBA stated succinctly in its submission: “Without DPAs, far fewer cases of wrongdoing would be brought to the public's attention” in the US and the UK.

Some of these calls for corporate diversion could also be read in support of the alternative explanations that Canada introduced corporate diversion to follow America's lead or to serve its national economic interest by creating business-friendly enforcement tools. As I discussed in section 2 above, the US pioneered corporate diversion as part of active foreign bribery enforcement. Further, nine submissions, all from the business community, argued that Canada needed corporate diversion for competitive reasons. The Business Council of Canada claimed: “The fact that DPAs already are in use in several OECD countries puts our firms at a competitive disadvantage.” Here the business council was pointing out that Canada's reliance on protracted criminal investigations and trials placed its firms at a disadvantage to peers in other states that could more quickly resolve allegations of wrongdoing with corporate diversion. The parliamentary secretary to the minister of justice and attorney general made a similar point at the Senate hearings, noting that remediation agreements will be helpful in “ensuring that Canada is competitive with other jurisdictions” (Mendicino, Reference Mendicino2018).

But while Americanization or concern with the competitiveness of Canadian business can potentially explain Canada's consideration of corporate diversion broadly, these arguments fall short in accounting for the form of corporate diversion that Canada adopted in remediation agreements—with its legislative limits and court oversight. Court supervision can help to moderate any concerns of overzealous prosecutions and outsized punishments of prosecutors acting on their own. But legislative requirements and court approval can also slow down the resolution of corporate wrongdoing and create uncertainty as to whether corporate diversion will be used. All this is to suggest that if corporate diversion was intended primarily to bolster the competitiveness of Canadian firms, the flexible form of corporate diversion, like we see in the US, would have been an attractive option. Canada, however, adopted a strict form of corporate diversion, with legislative and judicial limits that narrow the chances of any company obtaining a remediation agreement.

In accounting for Canada's policy choice, there is evidence of transnational lawmaking and learning that favoured a strict form of corporate diversion. The background documents that the federal government provided for the consultation drew contrasts between the US and UK model and invited participants to weigh in (Government of Canada, 2017). There was remarkable consistency in the public submissions that Canada should follow the UK in its form of corporate diversion. As the government summarized, “the majority of participants favoured the UK model, which provides for strong judicial oversight throughout the DPA process” (Government of Canada, 2018: 16). What produced this support for a stricter form of corporate diversion was recognition of criticisms of the US's flexible version and that the UK's stricter model could mitigate these criticisms. As TI Canada stated, “Should DPAs be adopted in Canada, Transparency International Canada believes it is crucial to take precautions to avoid perceived pitfalls experienced in the United States.”

One of the main concerns with corporate diversion that TI Canada raised, and which many of the submissions echoed, is that corporate diversion fuels perceptions that corporations can “buy their way out of prosecutions,” where a DPA becomes simply “the cost of doing business.” A high level of prosecutorial discretion exacerbates this concern. Probe International, an NGO that made one of the few submissions opposed to corporate diversion, set out this critique: DPAs “turn the prosecution into prosecutor, judge and jury, thereby giving them boundless discretion, compromising justice, the rule of law, and public confidence in the judicial system.” Submissions that supported corporate diversion in Canada also recognized that this was a significant criticism of corporate diversion, particularly as practised in the US.

The UK's approach to corporate diversion offered a guide to mitigate this criticism with a legislative framework to govern corporate diversion and require judicial oversight. TI Canada wrote that “a DPA scheme should not be left solely to prosecutors’ initiative. Rather it should be set forth in a measured framework by legislators, who have the full authority and legitimacy to do so in the eyes of the public.” The British DPA provided such an example. Further, almost 40 per cent (16) of the submissions pointed favourably to the UK's requirement for court approval of DPAs and encouraged Canada to follow it. The CCEAC stated in its submission that “learning from the lessons from the US and UK, [Canada's] DPA process needs to be validated and approved by the courts.” Doing so, the CCEAC explained, will help to “strike the right balance” in ensuring that DPAs are not simply the “cost of doing business” or “default process” and that the criminal prosecution of corporations is still pursued when needed. Many business voices agreed. The Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters noted that “the main criticism is that DPAs allow organizations to ‘pay their way’ out of trouble. To deflect such critiques, the crown must carefully decide when a DPA is appropriate. The UK model allows for the agreement to be reviewed and confirmed by a judge, reassuring the public that justice has been served.” The submission from the law firms Osler and Cassels Brock put it even more directly: “The court has an important gatekeeper role and should not be seen as a ‘rubber stamp’. In this manner, Canada should borrow more from the United Kingdom's regime than from that of the United States.”

Support for the British model of corporate diversion carried over to the legislation that created remediation agreements. As the Criminal Code now requires, Canadian prosecutors, like their British counterparts, must apply to courts for approval of corporate diversion, and courts in both countries must assess whether the “the terms of the agreement are fair, reasonable and proportionate” (Crime and Courts Act, Schedule 17, section 8; Criminal Code, section 715.47(6)). Judges in Canada must also assess whether the agreement is “in the public interest” and in the UK must assess if the agreement is “in the interests of justice.” Both the British and Canadian laws on corporate diversion require that prosecutors consider similar criteria before beginning negotiations and that they exclude other criteria—notably, national economic interests and other impermissible considerations under Article 5 of the OECD Convention.

However, there are important distinctions between the British and Canadian laws. While UK legislation requires prosecutors to establish guidelines for when DPA negotiations can be commenced, Canadian law includes the requirements that prosecutors must consider before pursuing a remediation agreement in the Criminal Code. In addition, British prosecutors can consider collateral consequences in determining whether to negotiate a DPA, but these are not included among the listed factors that Canadian prosecutors must consider to negotiate a remediation agreement. Thus, corporate diversion in Canada can be seen as even stricter than in the UK and suggests that Canada went further to ensure that corporate diversion would be used judiciously. Doing so closely aligns Canadian corporate diversion with international NGO guidance. It may also indicate further learning from the UK following the 2017 Rolls-Royce DPA and Corruption Watch's questioning of whether its DPA regime ensured that corporate diversion was only being used in the right conditions.

5. Conclusions

This article has considered why Canada introduced corporate diversion and in the form of remediation agreements. In contrast to arguments that point to government capitulation to business interests, I have argued that understanding Canada's turn to corporate diversion requires looking to international monitoring of Canada's implementation of the OECD Convention and cross-national policy diffusion. Following the UK's lead on corporate diversion, with its legislative framework and judicial oversight, was a safe bet for Canada in trying to square the circle of appeasing criticism of its lagging anti–foreign bribery enforcement while ensuring broad support of the means that it used to do so. Ultimately, this suggests that regardless of the SNC-Lavalin case, there is good reason to think that corporate diversion would have made its way to Canada.

This research has shown that important inputs to the policy-making process in Canada lie transnationally—in international law, international monitoring and policy developments in other states—and not only the US. These findings also have implications for scholarship on state socialization, highlighting how naming and shaming can work with cross-national policy diffusion and learning to change state behaviour and points to exciting avenues for future research in exploring this connection. This research also has policy implications for corporate criminal law enforcement in Canada and the prospects for developing international standards on corporate diversion. Remediation agreements have been available in Canada since 2018 but have yet to be used. This fact raises questions as to whether the strict form of corporate diversion is limiting its use or whether the SNC-Lavalin scandal may have tarnished remediation agreements. Internationally, corporate diversion is becoming increasingly common in the enforcement of anti–foreign bribery laws, but this research further attests to the variation in how states are making use of these additional enforcement tools (OECD, 2019, 17: 141–51). It also suggests that a divide may be emerging between the US's flexible corporate diversion and the stricter form in more recent adopters such as the UK and Canada and called for by NGOs. Such a divide may make it challenging for the OECD to develop meaningful international standards on corporate diversion without at least implicitly criticizing either form and, particularly, the numerous US foreign bribery enforcement actions attained with its flexible model.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions for the article and Rebecca Sullivan and Jessi Gilchrist for their research assistance. My gratitude as well to Danielle Gilbert, Alexander Luscombe, Frances Rosenbluth, Grace Tran, Rachel Whitlark, participants at the University of Toronto's Law Faculty Workshop, and participants at McGill University's Politics of Corruption Prosecutions Workshop for their generous feedback on earlier drafts.

Appendix

This study draws on a variety of primary source documents: submissions to the federal government's 2017 public consultations on corporate diversion, documents produced by the federal government concerning the public consultation and the introduction of remediation agreements, documents from the OECD and NGOs monitoring the implementation of the 1997 Anti-Bribery Convention, and comparative legal and policy documents on corporate diversion in the UK and US. This appendix describes these documents in more detail, including how they were obtained and analyzed. As noted below, other than submissions to the public consultation, all of the documents are accessible online.

The study uses these primary source documents for two main purposes. First, the project examines legal and policy documents for concept formation—namely, to identify and compare the different forms that corporate diversion can take, including the flexible form of corporate diversion that developed in the US and the strict form that Canada adopted. Second, the project analyzes primary source documents as empirical evidence for why Canada turned to corporate diversion and in the form of remediation agreements. Here the study relies primarily on the public consultations and OECD and NGO monitoring documents; I discuss how I analyzed these documents to understand Canada's turn to a strict form of corporate diversion in section (e) below.

a. Public Consultations

In 2017, the Canadian federal government held public consultations called Expanding Canada's Toolkit to Address Corporate Wrongdoing, which included two “streams”: the Deferred Prosecution Agreement Stream and the Integrity Regime Stream. The Deferred Prosecution Agreement Stream focused on the possible introduction of corporate diversion in Canada, and the Integrity Regime Stream focused on potential reforms to the federal government's procurement and debarment policy. I submitted an Access to Information Act request to the Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) for all written submissions to the consultations; PSPC produced documents in response to my request in October 2021.

I focused my analysis on submissions to the public consultations that substantively engaged with corporate diversion and whether it should be introduced in Canada. This totalled 42 submissions, composed of 20 submissions from businesses and business groups, 9 submissions from law firms, 1 submission from the Canadian Bar Association, 3 submissions from NGOs and 9 submissions from individuals. Submissions from individuals were produced to me by PSPC without names or identifying information. Table 1 lists the submission to the public consultations on corporate diversion that I reviewed.

Table 1 Submissions to Public Consultations on Corporate Diversion

I excluded from my analysis submissions produced by PSPC that focused on reforms to the government's procurement and debarment policy. I also did not include in my review Bell's submission to the consultations on corporate diversion, as PSPC produced only the cover letter from Bell's submission and withheld the remainder, pursuant to the Access to Information Act, sections 20(1)(b) and 20(1)(c).Footnote 1 I included in my analysis a report published in July 2017 by the NGO Transparency International Canada, titled “Another Arrow in the Quiver? Consideration of a Deferred Prosecution Agreement Scheme in Canada.” While the report precedes the public consultations, several of the submission to the consultations refer to and draw on Transparency International Canada's report.Footnote 2

The organizations that participated in the consultations are largely Canadian businesses and business associations and Canadian law firms. A handful of the participants have connections to other countries, including the PCL Family of Companies (a group of construction companies with headquarters in both Canada and the US), Ortus Strategies (a consulting firm based in Switzerland) and the Canadian offices of three global law firms: Baker McKenzie LLP, Norton Rose Fulbright LLP and Dentons LLP. The Canadian Centre of Excellence for Anti-Corruption and Probe International are both Canadian NGOs; Transparency International Canada is the Canadian chapter of the international NGO Transparency International.

b. Government of Canada Documents

In addition to the submissions to the public consultations, I reviewed documents created by the federal government for the public consultations on corporate diversion, as well as legal and policy documents related to Canada's implementation of the OECD Convention and the creation of remediation agreements.

Criminal Code. 1985. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-46/section-715.32.html (August 13, 2021).

Government of Canada. 2017. “Expanding Canada's Toolkit to Address Corporate Wrongdoing: The Deferred Prosecution Agreement Stream Discussion Guide.” https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/ci-if/ar-cw/aps-dpa-eng.html (August 13, 2021).

Government of Canada. 2018. “Canada to Enhance Its Toolkit to Address Corporate Wrongdoing.” https://www.canada.ca/en/public-services-procurement/news/2018/03/canada-to-enhance-its-toolkit-to-address-corporate-wrongdoing.html (August 13, 2021).

Government of Canada. 2018. “Expanding Canada's Toolkit to Address Corporate Wrongdoing: What We Heard.” https://www.tpsgc-pwgsc.gc.ca/ci-if/ar-cw/documents/rapport-report-eng.pdf (August 13, 2021).

Government of Canada. 2018. “Remediation Agreements and Orders to Address Corporate Crime: Backgrounder.” https://www.canada.ca/en/department-justice/news/2018/03/remediation-agreements-to-address-corporate-crime.html (August 13, 2021).

R. v. Karigar. ONSC 5199 (Ont. Sup. Ct. 2013). https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2013/2013onsc5199/2013onsc5199.html?autocompleteStr=R.%20v.%20Kariga&autocompletePos=2 (August 13, 2021).

R v. Karigar. ONSC 3093 (Ont. Sup. Ct. 2014). https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2014/2014onsc3093/2014onsc3093.html?autocompleteStr=R.%20v.%20Karigar&autocompletePos=1 (August 13, 2021).

R. v. Karigar. ONCA 576 (Ont. Ct. App. 2017). https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onca/doc/2017/2017onca576/2017onca576.html?resultIndex=1 (August 13, 2021).

Senate of Canada. 2013. Debates of the Senate. 1st Session, 41st Parliament, Volume 150, Issue 148. March 26. http://www.parl.gc.ca/Content/Sen/Chamber/411/Debates/149db_2013-03-26-e.htm?Language=E#41 (August 13, 2021).

Senate of Canada. 2018. Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs. Hearings on Division 15 and 20 of Part 6 of Bill C-74, An Act to Implement Certain Provisions of the Budget. May 30. https://sencanada.ca/en/Content/Sen/Committee/421/LCJC/54117-e (August 13, 2021).

c. OECD and NGO Monitoring Documents

I also analyzed documents created by the OECD and NGOs relating to the implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention. In particular, I reviewed documents from these organizations addressing Canada's implementation of the Convention, as well as documents on the enforcement of anti–foreign bribery laws, including the use of corporate diversion. These documents are as follows:

Corruption Watch. 2016. “Out of Court, Out of Mind: Do Deferred Prosecution Agreements and Corporate Settlements Fail to Deter Overseas Corruption.” https://web.archive.org/web/20161013132910/http://www.cw-uk.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Corruption-Watch-Out-of-Court-Out-of-Mind.pdf (August 13, 2021).

Corruption Watch. 2017. “A Failure of Nerve: The SFO's Settlement with Rolls Royce.” 2017. https://www.transparency.org.uk/failure-nerve-sfo-s-settlement-rolls-royce (August 13, 2021).

Corruption Watch, UNCAC Coalition, Transparency International and Global Witness. 2016. “Global Standards for Corporate Settlements in Foreign Bribery Cases.” March 11. https://uncaccoalition.org/letter-to-oecd-secretary-general-angel-gurria-global-standards-for-corporate-settlements-in-foreign-bribery-cases/ (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 1999. “Canada: Review of Implementation of the Convention and 1997 Recommendation.” http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/anti-briberyconvention/2385703.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2004. “Canada: Phase 2 Report on the Application of the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions and the 1997 Recommendation on Combating Bribery in International Business Transactions.” https://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/anti-briberyconvention/31643002.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2006. “Canada: Phase 2 Follow-up Report on the Implementation of the Phase 2 Recommendation on the Application of the Convention and the 1997 Recommendation on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions.” https://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/anti-briberyconvention/36984779.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2008. “United Kingdom: Phase 2bis: Report on the Application of the Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions and the 1997 Recommendation on Combating Bribery in International business Transactions.” https://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/anti-briberyconvention/41515077.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2010. “Phase 3 Report on Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in the United States.” https://www.oecd.org/unitedstates/UnitedStatesphase3reportEN.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2011. “Canada's Enforcement of the Foreign Bribery Offence Still Lagging; Must Urgently Boost Efforts to Prosecute.” March 28. http://www.oecd.org/corruption/canadasenforcementoftheforeignbriberyoffencestilllaggingmusturgentlyboosteffortstoprosecute.htm (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2011. “Phase 3 Report on Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in Canada.” http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/anti-briberyconvention/Canadaphase3reportEN.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2012. “Phase 3 Report on Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in the United Kingdom.” http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/UnitedKingdomphase3reportEN.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2013. “Canada: Follow-up to the Phase 3 Report & Recommendations.” https://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/CanadaP3writtenfollowupreportEN.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2016. “OECD Anti-Bribery Ministerial Meeting: Ministerial Declaration.” https://www.oecd.org/corruption/oecd-anti-bribery-ministerial-declaration.htm (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2017. “Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention: Phase 4 Report: United Kingdom.” https://www.oecd.org/corruption/anti-bribery/UK-Phase-4-Report-ENG.pdf (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2019. “Resolving Foreign Bribery Cases with Non-Trial Resolutions: Settlements and Non-Trial Agreements by Parties to the Anti-Bribery Convention.” https://www.oecd.org/corruption-integrity/reports/resolving-foreign-bribery-cases-with-non-trial-resolutions-e647b9d1-en.html (August 13, 2021).

OECD. 2020. “2019 Enforcement of the Anti-Bribery Convention.” http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/OECD-Anti-Bribery-Convention-Enforcement-Data-2020.pdf (August 13, 2021).

Transparency International. 2013. “Exporting Corruption: Progress Report 2013: Assessing Enforcement of the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery.” https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/exporting-corruption-progress-report-2013-assessing-enforcement-of-the-oecd (August 13, 2021).

Transparency International. 2018. “Exporting Corruption—Progress Report 2018: Assessing Enforcement of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention.” https://www.transparency.org/en/publications/exporting-corruption-2018 (August 13, 2021).

Transparency International UK. 2012. “Deterring and Punishing Corporate Bribery: An Evaluation of UK Corporate Plea Agreements and Civil Recovery in Overseas Bribery Cases.” https://issuu.com/transparencyuk/docs/policy_paper_series_1_-_deterring__ (August 13, 2021).

d. Comparative Legal and Policy Documents

The study also draws on primary source documents from the US and the UK on the use of corporate diversion in the enforcement on anti–foreign bribery laws, which are listed below.

United Kingdom

Bribery Act. 2010. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/23/contents (August 13, 2021).

Crime and Courts Act, Schedule 17. 2013. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2013/22/schedule/17/enacted (August 13, 2021).

R. v. Innospec. (Southwark Ct. 2010). https://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/Misc/2010/7.html (August 13, 2021).

Serious Fraud Office. 2008. “Tackling Corruption—Working Smarter.” https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20090416215855/http://www.sfo.gov.uk/publications/speechesout/sp_142.asp?id=142 (August 13, 2021).

Serious Fraud Office. 2009. “Approach of the Serious Fraud Office to Dealing with Overseas Corruption.” https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20090805162920/http://www.sfo.gov.uk/news/downloads/SFO-COP-dealing-with-overseas-corruption.pdf (August 13, 2021).

Serious Fraud Office. 2013. “Deferred Prosecution Agreements—Code of Practice.” https://www.cps.gov.uk/publication/deferred-prosecution-agreements-code-practice (August 13, 2021).

Serious Fraud Office. 2017. “SFO Completes £497.25 m Deferred Prosecution Agreement with Rolls-Royce PLC.” https://www.sfo.gov.uk/2017/01/17/sfo-completes-497-25m-deferred-prosecution-agreement-rolls-royce-plc/ (August 13, 2021).

SFO v. Rolls-Royce plc. Lloyd's Rep. FC 249 (Southwark Ct 2017). https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/sfo-v-rolls-royce.pdf (August 13, 2021).

United States

Department of Justice. 2018. “Justice Manual.” https://www.justice.gov/jm/justice-manual (August 13, 2021).

Department of Justice and Securities and Exchange Commission. 2020. “A Resource Guide to the U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.” Second Edition. https://www.justice.gov/criminal-fraud/fcpa-resource-guide (August 13, 2021).

Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. 1977. 15 USC §§78dd-1 to 78dd-3. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/15/78dd-1 (August 13, 2021).

e. Analyzing Primary Source Documents

In analyzing the primary sources documents, my research was guided by qualitative historical analysis and “the use of primary or secondary source material as data or evidence” (Thies, Reference Thies2002: 351). As Cameron Thies explains, qualitative historical analysis entails a “critical reading of sources” to “synthesize[s] particular bits of information into a narrative description or analysis of a subject” (Thies, Reference Thies2002: 351). Specifically, this study uses primary source documents to construct an analysis of how Canada came to adopt corporate diversion in the form of remediation agreements. Here I drew on a range of primary source documents, namely written submissions to the public consultations on corporate diversion, documents from the federal government relating to the public consultations, the OECD Convention and remediation agreements, as well as OECD and NGO monitoring documents. I paid careful attention to the sequencing of events (George and Bennett, Reference George and Bennett2005: 13) in Canada's implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention and enforcement of its anti–foreign bribery law, particularly in relation to international monitoring of Canada and implementation of the Convention in other OECD countries.

Like all approaches, qualitative historical analysis has limitations that are important to bear in mind. In particular, one limitation arises from this study's reliance on the submissions to the public consultation for evidence of why Canada adopted corporate diversion and in the form of remediation agreements. My analysis identifies and focuses on themes in the consultations that were raised by multiple submissions; but it is possible that the government gave greater weight to some submissions than to others. In addition, Thies notes that there are limitations to qualitative historical analysis from “investigator bias and unwarranted selectivity in the use of source material” (Thies, Reference Thies2002: 352). As I describe below, I sought to minimize investigator bias through the identification of alternative explanations for Canada's adoption of remediation agreements and exploration of these alternatives in the primary source documents. Selectivity of source materials is difficult for researchers to fully mitigate, given that any documentary record offers only a partial accounting of events (Thies, Reference Thies2002: 356–59). For instance, the OECD documents addressing the implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention are limited by what information states share with the OECD and decisions within the OECD as to what aspects of a country's implementation to highlight in its reports or press releases. Similarly, OECD ministerial declarations can reflect priority areas of the organization or leading member states, as well as compromises among member states. This study has drawn on multiple documents where possible to address any selectivity in the sources—for example, considering both Transparency International's and the OECD's assessments of the implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention.

An example of how I used qualitative historical analysis is in my examination of the written submissions to the public consultations on corporate diversion for evidence of why Canada adopted corporate diversion and in the form of remediation agreements. I focused first on whether the submission supported or opposed the introduction of corporate diversion in Canada. To make this assessment, I looked for clear statements in the submission of the author's position. This meant that I coded the statement by the Conseil du patronat du Québec (CPQ) that “the CPQ is favorable to the implementation of a DPA scheme in Canada” as supporting the introduction of corporate diversion. By contrast, I identified the statement by Probe International that “it is our view that Canada should not adopt DPAs” as opposing corporate diversion. There were only two submissions that I analyzed, both submitted by individuals, that did not express a clear position in support or opposition to the introduction of corporate diversion.

From here, I reviewed the submissions for arguments from the participants regarding why corporate diversion should or should not be adopted in Canada. As common themes began to emerge across the submissions, I grouped the submissions that expressed similar rationales. For instance, many of the submissions made explicit arguments that the introduction of corporate diversion would increase the enforcement of corporate and economic crime. Here the submission of one of the NGOs, the Canadian Centre for Excellence in Anti-Corruption, is illustrative. Their submission states that “having a DPA regime will provide an incentive for companies to voluntarily disclose wrongdoings, cooperate with authorities and seek quick resolutions which will save time, money and resources for both the companies and the state. This in turn will increase the number and frequency of cases being adjudicated.” Other submissions did not explicitly connect corporate diversion to an increase in enforcement actions but made a related argument that corporate diversion would increase self-reporting of wrongdoing by corporations. For instance, the Supply Chain Management Association's (SCMA's) submission argued the corporate diversion will “encourage companies to acknowledge, self-report, and take measures to correct wrongdoing” and did not directly state that this would increase enforcement. I noted these distinctions, classifying the SCMA's submission as supporting corporate diversion, on the grounds that it would increase self-reporting, and classifying the CCEAC submission as supporting corporate diversion, on the grounds that it would increase self-reporting and enforcement.

For the submissions that supported the introduction of corporate diversion in Canada, I also reviewed them for recommendations and arguments on the form of corporate diversion that Canada should adopt. Here I noted any explicit recommendations for a form of corporate diversion as practised in another country. This allowed me to keep track of and consider evidence in support of diffusion via policy learning. It also allowed me to explore evidence of the alternative explanation that the adoption of corporate diversion in Canada is a part of a broader trend of the Americanization of Canadian law.

In reviewing the submissions, I also reviewed the documents for support of another alternative explanation: that Canada adopted remediation agreements to further its national economic interest and bolster the competitive position of Canadian business. For instance, the Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters wrote in their submission that “Canadians have already lost significant business because of the absence of a DPA,” which I categorized as an argument for corporate diversion to alleviate competitive pressure. Further, I looked for explicit connections between competition-driven arguments for corporate diversion and the form of corporate diversion that Canada should adopt, but I found little direct evidence. Altogether, qualitative historical analysis allowed me to organize my examination of the various primary source documents relating to Canada's ongoing implementation of the Anti-Bribery Convention and the introduction of corporate diversion and assess evidence of transnational lawmaking in the policy-making process that produced remediation agreements.