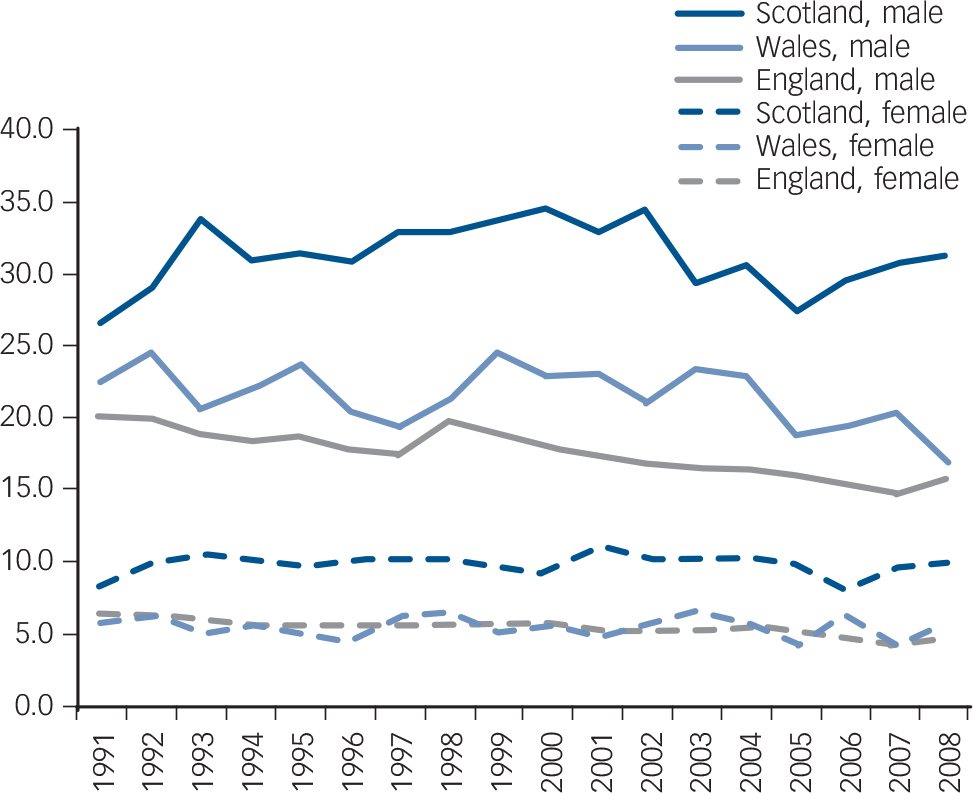

Our rationale for investigating suicides in England & Wales jointly was twofold. First, although the male suicide rate has been somewhat higher in Wales than in England in recent years, the difference was not nearly as marked as that for Scotland v. England, as shown in Fig.1. The pattern of change in trends over the past two decades was also more similar for England v. Wales than when compared with Scotland. During the same period, there was little difference in the female suicide rate between England and Wales, while the female rate in Scotland was significantly higher than in the other two countries.

Our second reason was a technical one. At the beginning of our study, we sought advice from the General Register Office for Scotland and the Office for National Statistics about the comparability of their routinely reported suicide data. Because of differences in how suicide data were typically extracted by the two organisations, based on the usual residence and place of death of the deceased, it was concluded that using data from England & Wales combined would give us the best comparison with the Scottish data.

The cultural and ascertainment explanations of higher rates of suicide by drowning in Scotland proposed by Evans are interesting and plausible. An investigation of suicides in Scotland by Platt et al has reported that drowning as a method of suicide is more common in the Highlands and the Islands than other local areas in the country. Reference Platt, Boyle, Crombie, Feng and Exeter1 This method of suicide, however, would not have accounted for much of the overall differential between Scotland and England & Wales, for two reasons. First, it is a relatively rare method, accounting for 5% of all suicide cases in England & Wales, and 10% of those in Scotland, between 2000 and 2008,

Fig. 1 Age standardised suicide rates by country, 1991–2008 (persons aged 15 and over). Data from General Register Office for Scotland and the Office for National Statistics.

and therefore would have made only a minor contribution to the overall between-country differential in risk. Second, although Scotland may contain the great bulk of all the standing water in Great Britain, most Scottish people who died by suicide lived in large urban areas located a considerable distance from the Highlands, where access to such a suicide method was unlikely to be any greater than was the case in England & Wales.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.