Introduction

Research on children’s moral self-concept (MSC) has gained attention in the field of moral development because it connects moral cognition with moral behaviors (Smetana & Yoo, Reference Smetana, Yoo, Killen and Smetana2022). In early childhood, MSC describes how young children perceive themselves as moral agents (Kingsford et al., Reference Kingsford, Hawes and de Rosnay2018; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015), specifically regarding their predispositions for prosociality (e.g., helping, sharing, and comforting; Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021) and aggression (e.g., actions which cause harm to others; Gniewosz et al., Reference Gniewosz, Sticker and Paulus2022; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015). Young children display varying preferences and aversions toward prosocial and aggressive motifs (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Aksan and Joy2007; Krettenauer et al., Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021). However, multidimensional patterns of MSC in early childhood are not well understood. This is important to understand as integrating one’s moral values with self-concept may influence one’s moral actions, including prosocial (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021) and aggressive behavior (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015).

Few studies have focused on how MSC relates to current or future moral behaviors in young children. Although preschool and elementary students’ explicit MSC may relate to prosocial behavior (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2021, Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2023), aggressive behavior in early childhood remains less explored. This study has two goals: (1) use person-centered approaches to detect latent groups of preschool children’s MSC and (2) examine relations between MSC and teacher-reported moral behaviors both concurrently and at a 6-month follow-up.

Development of moral self-concept in early childhood

The MSC is hypothesized to be a precursor to a more abstract understanding of moral inclinations in adolescence and adulthood, referred to here as moral identity – how valued being moral is to one’s sense of self (Krettenauer & Hertz, Reference Krettenauer and Hertz2015). Although both the MSC and moral identity focus on one’s inclinations, their relations are not well understood (Kingsford et al., Reference Kingsford, Hawes and de Rosnay2018). In adolescence and adulthood, moral identity and its relations to moral behaviors have been more thoroughly explored, but not the MSC in early childhood (Kingsford et al., Reference Kingsford, Hawes and de Rosnay2018).

Researchers theorize that young children develop an understanding of their own morality through experiences, socialization, and recalling moral events (Hardy & Carlo, Reference Hardy and Carlo2011; Kingsford et al., Reference Kingsford, Hawes and de Rosnay2018; Kochanska, Reference Kochanska2002). Early work suggested that moral development begins in infancy by way of social referencing during repeated emotional communication, therefore teaching children the boundaries of right and wrong (Emde et al., Reference Emde, Biringen, Clyman and Oppenheim1991; Emde, Reference Emde1992). By age 2, children view themselves as moral agents (i.e., meeting typical expectations and following rules; Emde et al., Reference Emde, Biringen, Clyman and Oppenheim1991; Emde, Reference Emde1992; Kochanska, Reference Kochanska2002). By age 4, they develop an internally consistent MSC that reflects their view of themselves as a “good” or “bad” person (Kochanska, Reference Kochanska2002). Through continued personal experiences with prosocial or aggressive behavior, children accumulate moral knowledge corresponding with rule internalization (Kochanska, Reference Kochanska2002; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021). When caregivers provide feedback to young children on children’s accidental or intentional immoral actions, such as explaining why pushing a friend off a swing is wrong, and teaching appropriate behaviors (e.g., apologizing to a friend and making sure the friend is alright), it positively shapes children’s internalization of “right” and “wrong” (Krettenauer et al., Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013). Historically, work connecting self-concepts with actions has viewed feedback as the main avenue for building and modifying self-concepts in children (Grusec & Redler, Reference Grusec and Redler1980; Mills & Grusec, Reference Mills and Grusec1989).

Children’s engagement in both moral and immoral actions, and the feedback they receive, is central to building one’s MSC (Hardy & Carlo, Reference Hardy and Carlo2011; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010), and by age 5, there are clear differences in children’s selection of moral preferences and moral aversions (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Aksan and Joy2007; Krettenauer et al., Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013). Differences in moral preferences can be seen in responses by 5-year-olds to an MSC puppet interview, in which children are presented with two puppets that say opposing statements (preference or aversion) about moral inclinations (Krettenauer et al., Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2021, Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2023). Children identify with puppets expressing moral inclinations (i.e., aggression and prosocial inclinations) to differing degrees, and these differences reflect individual perspectives of the internalization of morality. These individual preferences for prosocial inclinations maintain some stability between early childhood and middle childhood (Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2023). In general, most children tend to show an inclination toward prosociality and a disinclination toward aggressive motives (Krettenauer et al., Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013).

MSC and prosocial behaviors

Prosocial behaviors – actions that occur to benefit others or strengthen relations (Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Spinrad, Eisenberg, Damon and Lerner2006) – may include helping, comforting, and sharing. Alternatively, these can be characterized as behaviors that meet others’ needs: specifically, instrumental needs (requiring assistance to meet a goal), socio-emotional needs (requiring assistance in alleviating negative emotions), and material needs (providing access to resources; Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, Reference Dunfield and Kuhlmeier2013; Paulus, Reference Paulus2018), respectively.

Hardy and Carlo (Reference Hardy and Carlo2011) suggest that children’s conceptions of their own moral agency impact their future participation in moral behaviors. For instance, experiences related to helping and the corresponding feedback from adults (e.g., “That was very nice of you”) support the development of self-perceptions of individual helping behaviors (e.g., the child thinks of themselves as helpful). How a child views themselves as a good helper would then directly influence future decision-making regarding helping others. As one example, 6- to 8-year-olds behave more generously when they are first prompted to think of a time when they were generous (Tasimi & Young, Reference Tasimi and Young2016). In addition, perceptions of the self in middle childhood may be modified by communicating attributions that may in turn impact future behavior (Grusec & Redler, Reference Grusec and Redler1980).

In middle childhood and adolescence, the importance of moral identity for prosocial behaviors is well documented (Aquino et al., Reference Aquino, McFerran and Laven2011; for review see Hertz & Krettenauer, Reference Hertz and Krettenauer2016). Those who view themselves as moral engage in more prosocial behavior than those who view themselves as less moral (Hertz & Krettenauer, Reference Hertz and Krettenauer2016). However, there may be an age-related increase in the correspondence between MSC and prosocial behavior, such that with age children’s MSC is a more robust representation of their behavior. For instance, Christner et al. (Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020) explored how children’s MSC related to prosocial behaviors of sharing items (e.g., stickers or erasers) with a friend who had none. By middle childhood (8–9-year-olds), children who viewed themselves as moral agents participated in more prosocial behavior than those who viewed themselves less morally; however, younger children’s (6–7-year-olds) MSC did not correspond with their behavior.

To our knowledge, only two studies have explored how MSC relates to prosocial behavior in preschool-aged children. Sticker et al. (Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021) found that 4–6-year-olds’ MSC was directly related to children’s prosocial behaviors of sharing and comforting, but was unrelated to children’s helping behaviors. Exploring positive MSC and prosocial behavior longitudinally, Sticker et al. (Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2023) discovered that MSC motifs related to sharing predicted sharing behavior. However, MSC dimensions of helping and comforting did not predict their corresponding behavior. In light of research on older children, it is likely that preschoolers’ MSC does not correspond with children’s prosocial behaviors or at least does not correspond with discrete components of prosocial behavior.

MSC and aggression

In adolescence and adulthood, moral identity is negatively associated with aggressive behaviors (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Bean and Olsen2015; Hertz & Krettenauer, Reference Hertz and Krettenauer2016; Smetana & Yoo, Reference Smetana, Yoo, Killen and Smetana2022). As people desire consistency between their self-views of morality and action, the desire to view oneself in a certain manner may motivate actions (Krettenauer, Reference Krettenauer2022); therefore, individuals who view themselves as having a weaker morality are more likely to participate in aggressive behaviors (Hardy et al., Reference Hardy, Bean and Olsen2015; Hertz & Krettenauer, Reference Hertz and Krettenauer2016).

Similarly, Sengsavang and Krettenauer (Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015), based on a sample of 198 children between the ages of 4 and 12, found that children who were reported by parents as more aggressive identified less with the prosocial dimensions (i.e., helping, sharing, and caring) of MSC and more with the dimensions of aggression and stealing compared with children who displayed less parent-reported aggression. Kochanska and colleagues (2010) explored 5-year-olds’ MSC and its ability to predict antisocial behavior (in this case, problematic behavior including oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder) 1 year later. They found that children who perceived themselves as prosocial and had an aversion to immoral motives were more likely to be described by parents and teachers as prosocial 1 year later and had fewer challenges associated with antisocial behavior than children who did not view themselves as comparatively moral.

To our knowledge, all previous studies of MSC and aggression considered unidimensional aggression. A more nuanced relation, such as considering the motivations of aggression, is underexplored. Proactive aggression is considered “cold-blooded,” goal-directed, and occurs to obtain objects (e.g., toys) or power (Dodge, Reference Dodge, Pepler and Rubin1991; Jambon & Smetana, Reference Jambon and Smetana2018). Reactive aggression, in contrast, occurs in response to a provocation or threat, is typically “hot-blooded,” and is driven by anger or hostility (Card & Little, Reference Card and Little2006; Dodge, Reference Dodge, Pepler and Rubin1991). Proactive aggressors usually have better emotion regulation skills and experience less peer rejection than reactive aggressors, whereas reactive aggressors are often viewed as immature by peers and have difficulty with executive functioning and emotional regulation skills (Arsenio et al., Reference Arsenio, Adams and Gold2009; Ostrov et al., Reference Ostrov, Murray-Close, Godleski and Hart2013).

Importantly, proactive and reactive transgressors differ quite robustly in how they process moral versus conventional transgressions (social rules agreed upon by society, e.g., not throwing away all of your trash after eating lunch in a classroom that has rules about cleaning up; Smetana et al., Reference Smetana, Jambon, Ball, Killen and Smetana2014). Reactive aggressors easily distinguish between moral and conventional concerns and easily identify that moral transgressions are more severe than conventional transgressions, whereas proactive aggressors have difficulty distinguishing between moral and conventional concerns and view both types of transgressions equivalently (Jambon & Smetana, Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2014, Reference Jambon and Smetana2018; Orobio de Castro et al., Reference Orobio de Castro, Verhulp and Runions2012). Proactive aggressors may hide their difficulty with moral reasoning by using their adept social skills (Hawley & Geldhof, Reference Hawley and Geldhof2012).

Although proactive and reactive aggressors differ in their moral reasoning, the connection between their behaviors and their MSC is unexplored. As reactive aggressors may have difficulty with executive functioning and emotional regulation skills (Arsenio et al., Reference Arsenio, Adams and Gold2009; Ostrov et al., Reference Ostrov, Murray-Close, Godleski and Hart2013), and their aggression occurs in the heat of the moment, without prior contemplation (Card & Little, Reference Card and Little2006; Dodge, Reference Dodge, Pepler and Rubin1991), it is likely that these aggressive acts are not morally or immorally motivated but rather occur due to cognitive immaturity. Proactive aggressors, in comparison, plan aggressive acts to accomplish a goal (Jambon & Smetana, Reference Jambon and Smetana2018) and have difficulty with moral reasoning (Jambon & Smetana, Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2014, Reference Jambon and Smetana2018; Orobio de Castro et al., Reference Orobio de Castro, Verhulp and Runions2012). Considering that reactive aggressors are more adept at evaluating and prioritizing moral concerns, compared with proactive aggressors, and use aggression in the heat of the moment without meditation, reactive aggressors likely have more positive MSC (i.e., show greater concern for others’ well-being) than proactive aggressors.

Current study

One’s MSC is theorized to help guide prosocial behavior and aggression (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021). Numerous studies demonstrate that the MSC and moral identity are important positive predictors of prosocial behaviors and a negative predictor of aggressive behavior in middle childhood and adolescence (Hardy & Carlo, Reference Hardy and Carlo2011; Hardy et al., Reference Hardy and Carlo2014, Reference Hardy, Nadal and Schwartz2015). Yet, few studies have examined this in early childhood (Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021). The current paper aims to address this lacuna by taking a person-centered approach by examining MSC – that is, identifying latent profiles of MSC – and to use these profiles to detect differences in teacher-reported moral behavior concurrently and 6 months later.

Latent profiles are valuable as they allow for an integrated understanding of multiple heterogeneous characteristics and identify subgroups that display similar patterns (Lanza & Cooper, Reference Lanza and Cooper2016). To our knowledge, no studies have used a person-centered approach to understand comprehensive, multidimensional MSC profiles in early childhood. A study in adulthood reveals that latent classes of moral identity are likely. Hardy et al. (Reference Hardy, Nadal and Schwartz2017) used latent class analysis to form profiles using three identity constructs: personal identity, religious identity, and moral identity. Three groups were found, which were referred to by the authors as integrated (high levels of all three identity types), moral Iidentity focused (high levels of moral identity, moderate levels of personal identity, and low levels of religious identity), and religious identity focused (moderate levels of religious identity and low levels of moral and personal identity). Although their profiles were not specific to moral identity, when the moral identity construct was compared between the three classes, groups significantly varied. It is, therefore likely, that patterns of moral identity exist.

In early childhood, Christner and Paulus (Reference Christner and Paulus2022) took a person-centered approach exploring positive (i.e., prosocial) MSC profiles in early childhood, comprised of sharing, sharing behavior, and normative stances. Christner and Paulus (Reference Christner and Paulus2022) found that children tend to diverge in their preferences for sharing. When combined with the larger body of work on children’s MSC, which demonstrates that children display both preferences for and aversions to moral motives, it is likely that latent classes exist (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015; Sengsavang et al., Reference Sengsavang, Willemsen and Krettenauer2015; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021).

Several themes arise based on previous studies examining MSC and behavior in early childhood. First, children who have a more moral MSC (i.e., show stronger concern for others’ well-being) are more likely to engage in prosocial behavior (Christner & Paulus, Reference Christner and Paulus2022; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2021, Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2023). Second, children with less moral MSC are more likely to engage in behaviors of aggression (Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015). Nevertheless, although children express inclinations for and aversions to moral motives (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015; Sengsavang et al., Reference Sengsavang, Willemsen and Krettenauer2015; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021), people have enhanced views of their own morality wherein individuals view themselves as moral beings (Batson et al., Reference Batson, Thompson, Seuferling, Whitney and Strongman1999; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Prooijen and Lange2019; Tappin & McKay, Reference Tappin and McKay2016). Specifically, in regard to MSC, most children express a tendency toward prosociality and a disinclination toward aggressive motives (Krettenauer et al., Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013). Therefore, we anticipate that we will discover, although exploratory, at least two positive MSC clusters: (1) a group of children with preferences toward moral inclinations (i.e., preference toward prosocial motivations and avoidance of aggressive motivations) and (2) a group of children with a preference for both moral and immoral inclinations (i.e., preference toward prosocial and aggressive motivations).

Once MSC profiles are identified, we will use these to examine differences in reactive aggression, proactive aggression, and prosocial behavior as assessed by teachers concurrently and 6 months later. Research on aggression and prosocial behaviors has demonstrated that prosocial and some aggressive behaviors are developmentally appropriate for preschool-age children (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Vaillancourt, Barker, Nagin and Tremblay2007; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Fabes, Spinrad, Eisenberg, Damon and Lerner2006; Persson, Reference Persson2005; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Miller, Fagbemi, Côté and Tremblay2007). We therefore anticipate that groups will display both moral behaviors (i.e., prosocial and aggression) to varying degrees. Although both hypothesized MSC groups are anticipated to display a preference toward prosocial motives, they are hypothesized to vary in regard to aggressive motives. Research that compartmentalizes MSC suggests that children who identify with immoral inclinations are more likely to engage in less prosocial behavior and more aggressive behavior (Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015). As we expect different patterns of aggressive motives between groups, groups will likely display differing prosocial and aggressive behavior.

More specifically, considering age-appropriate behaviors and unidimensional patterns of MSC and behavior – wherein children with high moral motives may participate in prosocial behavior to a greater degree and less aggression than children who have less moral motives (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Koenig, Barry, Kim and Yoon2010; Sengsavang & Krettenauer, Reference Sengsavang and Krettenauer2015; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021) – we hypothesize the following relations between multidimensional MSC groups and behaviors:

First, we hypothesize that children in the “more moral” (i.e., preference toward prosocial dimensions and aversion to harm) group will participate in more prosocial behaviors and less aggressive behaviors (reactive and proactive) than the other groups. Second, we hypothesize that the group with a preference toward both prosocial and aggressive motivations, relative to the other group, will display proactive aggression and prosocial behavior, a pattern referred to by Hawley (Reference Hawley2003) as “bi-strategic controllers.”

Method

Participants and procedures

After we obtained ethical approval from the relevant university’s Institutional Review Board, 106 children (M age = 52.78 months, SD = 6.61 months, range: 37–64 months, 51% boys) and their caregivers took part in this study. Participants were recruited through head start preschool programs in an economically impoverished urban area in the northeast region of the United States (see Table 1 for demographic information). At the second measurement, all 106 children were retained and participated.

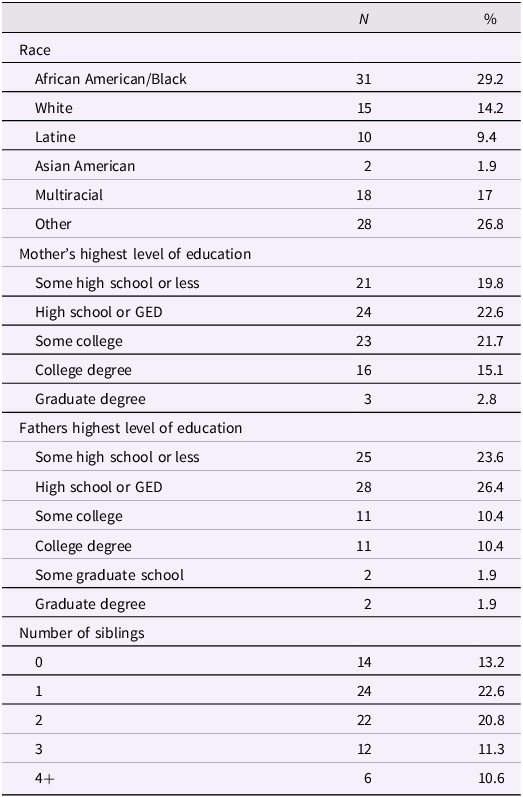

Table 1. Demographic information at Time 1

Note. N = 106, M age = 52.78 months (37–64 months), SD = 6.61 months, 51% boys, annual income = $23,030 (median = $18,000; [$1,100– $85,000]).

Caregivers received demographic and consent forms from the schools. Children completed the MSC interview in the fall semester after providing verbal assent. One of eight trained undergraduate researchers interviewed children one on one in a quiet place in their respective schools. Interviews were audiotaped and later transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions were then coded by a team of trained graduate researchers. Parents received $5 in each wave of the survey; they received an additional $5 if their children participated. Children received stickers for participating in the study, irrespective of interview completion.

During work hours, the head teacher in each class completed behavioral surveys for each child both in the fall (Time 1, hereafter T1) and subsequent spring (Time 2, hereafter T2). Teachers received up to $50 for classroom materials as a thank you, depending on the number of surveys completed.

Measures

Children’s moral self puppet interview

To assess children’s MSC, a modified version of Krettenauer et al.’s (Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013) puppet interview was used. This interview is frequently used with children between the ages of 4–6 (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2021, Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2023), and has been used with children as young as age 3 (Baker & Woodward, Reference Baker and Woodward2023). The puppet interview consists of 18 short videos of statements between 2 opposing puppets regarding their preferences for, or aversions to, (im)moral behavior (e.g., “I like to be kind to others” vs. “I do not like to be kind to others”). Although Krettenauer et al. (Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013) used puppets resembling humans, we chose to use puppets resembling humanoid monsters (one green, one orange, but otherwise identical). This decision was made so that children’s perceptions of puppet gender and/or race would not impact their responses. Videos were designed such that puppet positions in the videos (left or right) and preferences (moral or immoral) were counterbalanced and randomized across video order.

After each video, children saw a still photo of the two puppets and were asked which of the two puppets most aligns with their moral character (i.e., “What about you, are you more like Iggy or Ziggy?”). Then, children were asked to report the magnitude of their preferences (“Okay, you’re like [Iggy/Ziggy], how much are you like that? A little, a medium amount, or a lot?”). As the researcher asked this last question, they pointed to a series of images of the green or orange puppet of varying sizes (e.g., the researcher pointed to the smallest image when saying “a little” and to the largest image when saying “a lot”). As only audio recording was approved by the school administration, in order to maintain the reliability of the responses, the interviewers verbally repeated each response to ensure responses were recorded correctly (e.g., “Okay, you pointed at Ziggy”). Audio recordings were later transcribed, and inter-rater reliability of the transcription for 20% of cases (N = 22) was excellent (Kappa = .91).

Although Krettenauer et al. (Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013) used a 5-point scale that included a neutral middle option, here we use an adapted 6-point scale with dichotomous forced choice (i.e., no neutral middle option; Baker & Woodward, Reference Baker and Woodward2023). The adapted scale was selected for two reasons. First, previous studies had few middle selection responses (Gniewosz et al., Reference Gniewosz, Sticker and Paulus2022; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2023). Second, when considering the bipolar nature of the scale (Tay & Jebb, Reference Tay and Jebb2018) with the same behaviors in opposition (e.g., “I like taking turns” vs. “I don't like taking turns”), having a middle option may allow for the collection of unsure responses (Kulas et al., Reference Kulas, Stachowski and Haynes2008; Nadler et al., Reference Nadler, Weston and Voyles2015). The 6-point scale used here ranged from 1 = low agreement with the item (i.e., “not like me”) to 6 = high agreement with the item (i.e., “a lot like me”), resulting in higher scores indicating that an item strongly represented that child’s view of the self. Of the 18 items, 6 assessed prosocial predispositions (e.g., comforting a peer), and 6 assessed aggressive predispositions (e.g., pushing). The remaining six items assessed children’s tendency to respond in socially desirable ways. This differs slightly from Krettenauer et al. (Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013), in that they focused on “antisocial” behavior more broadly, which included items about stealing, physical aggression, and verbal aggression; here, we omitted the items on stealing. The aggression items in this scale do not capture functions of aggression (i.e., proactive and reactive aggression). Again, a high score on any item indicated the child felt represented by that item.

Once items were coded, consistent with Krettenauer et al. (Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013), we conducted a principal components analysis with oblimin rotation and Kaiser normalization to determine the dimensionality of the scale. Although the scale was developed and confirmed by Krettenauer et al. (Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013), our sample differs in context from the sample tested by Krettenauer’s team; namely, our sample comes from urban, economically impoverished communities. Given that recent developmental research highlights the importance of eschewing the idealization and assumed universality of results from convenience samples, we felt it best to psychometrically evaluate this scale with our sample.

Results, confirmed by the Scree plot, indicated a four-factor solution. The eigenvalues for these four factors were (1) 3.13, (2) 2.42, (3) 1.73, and (4) 1.31. Items were retained if they had a factor loading ≥ .40. No items loaded on more than one factor. The four factors were identified as (1) prosocial: socio-emotional support (e.g., comforting a peer when the peer is hurt), Guttman’s λ2 = .75; (2) prosocial: instrumental support (e.g., helping), λ2 = .60; (3) aggression, λ2 = .68; and (4) social desirability, λ2 = .66. Although these reliability estimates are somewhat lower than Nunnally’s (Reference Nunnally and Wolman1978) recommended threshold of .70 in adult samples, Krettenauer et al. (Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013) and Sticker et al. (Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021) report similar or lower reliability estimates for this task when used with preschool and kindergarten children. The full puppet interview scale can be found at: https://osf.io/vf73m/?view_only=cc8b1758410e4f368da4ff85fce71e5b.

Aggressive and prosocial behaviors

Lead teachers completed the 14-item Preschool Proactive and Reactive Aggression–Teacher Report survey (PPRA-TR; Ostrov & Crick, Reference Ostrov and Crick2007) to assess children’s aggressive and prosocial behavior, along with a four-item prosocial subscale from the Preschool Social Behavior Scale (PSBS; Crick et al., Reference Crick, Casas and Mosher1997) to examine prosocial behavior. The PPRA-TR, written at a 5th-grade reading level, assesses both proactive and reactive aggression using six items for each aggressive subtype (e.g., “This child often hits, kicks, or pushes to get what he or she wants” to assess proactive, and “If other children anger this child, s/he will often hit, kick, or punch them” to assess reactive), and two items to assess prosociality (e.g., “This child will often include others after they have cooperated with her/him”). Including the four items from the PSBS (e.g., “This child is helpful to peers”), there are a total of six items that assess prosocial behaviors. Teachers used a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (always or almost always) to rate how often the focal child engaged in each behavior from both the PPRA-TR and PSBS.

These subscales were reliable in previous studies (Murray-Close & Ostrov, Reference Murray-Close and Ostrov2009; Ostrov & Crick, Reference Ostrov and Crick2007) and here, both at T1 (reactive Guttman’s λ2 = .76, proactive λ2 = .80, prosocial λ2 = .72) and T2 (reactive λ2 = .81, proactive λ2 = .81, prosocial λ2 = .73). Thereafter, scores from the items from each subscale were averaged to create subscale composite scores. A high score on any item indicates frequently recurring behavior (i.e., aggression or prosocial).

Attrition and missingness

At T1, older children were more likely to have missing data (children with missing data were approximately 54.67 months old, and children for whom no data were missing were on average 52.36 months old). Other demographic variables also contributed to missingness at T1; missingness was more prevalent among children living with just their mother (26.5% vs. 2.6%), children with no siblings (51% vs. 7.7% for children with just one other sibling), children living below the poverty threshold (21% vs. 10% for children living above the poverty threshold), and children with highly educated mothers (33% for children of mothers with graduate degrees vs. 0% for all other children). Missingness at T2 was likewise explained by child age, parent education, and family size.

To understand the pattern of missingness and decide how to address it, we conducted a missing value analysis on all study variables (i.e., MSC, behavior, and demographics), and the results indicated that missingness was likely related to observed variables, χ2 (124, N = 106) = 178.94, p = .001. Based on the pattern of missingness described above – that is, that missingness was based on demographic variables, but not based on any variables of interest – these patterns suggest that missing data was largely explained by family characteristics unrelated to child behavior. The term for this pattern of missingness is “missing-at-random,” in that missingness can be explained by other measured variables in the data set and does not appear to be related to the variables of interest (i.e., missing data does not appear to be related to children’s behavior; Dong & Peng, Reference Dong and Peng2013; Heitjan & Basu, Reference Heitjan and Basu1996). To address missingness, we used the expectation maximization algorithm given that it produces the least biased estimates based on previous demonstrations of our sample size and rate of missingness (Dong & Peng, Reference Dong and Peng2013; Ibrahim & Molenberghs, Reference Ibrahim and Molenberghs2009; Schlomer et al., Reference Schlomer, Bauman and Card2010). Given that no child had full missing datum at T2, this approach (expectation maximization) allowed us to retain the full sample of 106.

Plan of analysis

Once missingness was addressed, we analyzed data in two phases: first, we identified clusters, or profiles, of children based on their MSC; second, we examined behavioral patterns across profiles for both aggressive and prosocial behavior.

Profiles of moral self-concept

For the first phase, we used IBM SPSS (version 28) to conduct a two-step cluster analysis (Bacher et al., Reference Bacher, Wenzig and Vogler2004) of children’s MSC. Two-step cluster analysis is an iterative hybrid technique for classifying participants in that it uses both hierarchical and partition (or “distance”) based methods to determine clusters (Han et al., Reference Han, Pei and Tong2012). Moreover, the two-step cluster analysis approach offers several strengths over alternative methods for profile identification, including the use of fit indices (Akaike information criterion, AIC, Akaike, Reference Akaike1987; Bayesian information criterion, BIC, Schwarz, Reference Schwarz1978) to determine the number of clusters, as well as including outliers, and is the most reliable of the approaches (Bacher et al., Reference Bacher, Wenzig and Vogler2004).

We included all three components of MSC (i.e., socio-emotional support, instrumental helping, and aggression) in the cluster analysis. Before conducting the cluster analysis, MSC variables were standardized (i.e., z-score transformation) to aid interpretability. For AIC and BIC, lower values indicate a better fit to the data. We also considered the silhouette coefficient (s) in determining model fit, for which higher values indicate greater distinction between clusters and greater cohesion within clusters (range of possible values: −1 < s > 1; Rousseeuw, Reference Rousseeuw1987). Two-step cluster analysis assumes that variables are relatively orthogonal, which was the case here. Additionally, although this clustering technique allows for the inclusion of categorical variables, in this case, we only included continuous variables in the analysis, and so we used the Euclidean distance approach.

Behavioral prediction analysis

Before examining the predictive value of MSC profiles on teacher-reported behaviors, we first examined possible predictors of MSC profiles from typical sociodemographic variables. This was done in order to consider possible control variables for later analyses. For this, we used multinomial logistic regression techniques, which are used to predict differences in categorical outcomes (i.e., MSC clusters). Here, we examined the Wald statistic to detect significant differences between clusters. For categorical demographic variables (i.e., gender), we use a chi-squared test. Once relevant covariates were identified, we used cluster membership identified in the first phase of analyses in a series of analysis of covariance to predict concurrent and subsequent teacher-rated behaviors. In these analyses, cluster membership was entered as an independent variable, relevant covariates were entered as a covariate, and the behavioral variable (e.g., T1 teacher-reported prosocial behavior) was entered as the dependent variable. For the analysis of change over time, the output variable was calculated Δbehavior=T2behavior-T1behavior, which was then used as the dependent variable.

Results

Preliminary analyses and descriptive statistics Footnote 1

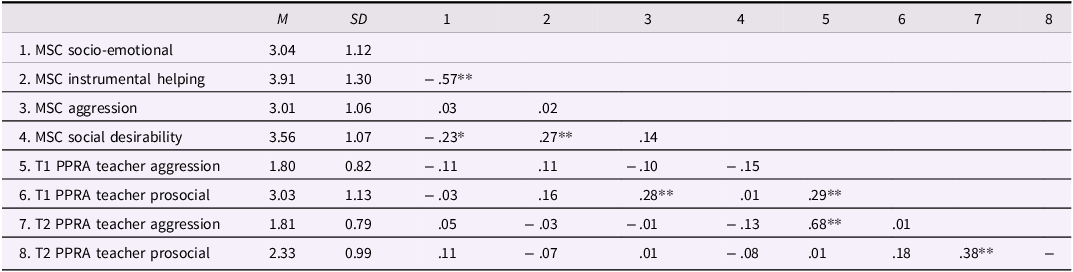

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all variables are in Table 2. The MSC variable for socio-emotional comfort was negatively correlated with the MSC variable for instrumental helping, and the MSC aggression variable was positively correlated with T1 prosocial behavior. In general, all teacher-reported behaviors were positively related to all other teacher-reported variables, with two exceptions. Prosocial variables, both T1 and T2, only correlated with variables measured at the same time (e.g., T1 prosocial behavior correlated with T1 reactive aggression). Given the very high correlations between proactive and reactive aggression at T1 (r = .898, p < .001) and T2 (r = .912, p < .001), and based on feedback from a helpful reviewer, we made the decision to collapse reactive and proactive aggression in further analyses. Analyses that parse reactive from proactive aggression can be found in Supplementary Materials.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations, means, and standard deviations among study variables

Note. MSC = moral self-concept; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; M = median; SD = standard deviation. For all MSC variables, values range from 1 to 6, with higher values indicating greater agreement with the respective concept. For all behavior variables, values range from 1 to 5, with higher values indicating a greater tendency to display that behavior. * p < .05, ** p < .01 (2-tailed).

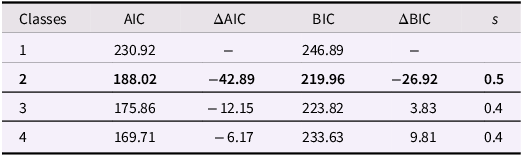

Cluster analysis results

To identify latent groups of children’s MSC, we considered 1–4-class solutions in the cluster analysis (see Table 3 for model fit comparisons). BIC values were lowest in the 2-class solution compared with the 1-, 3-, and 4-class solutions, indicating a better fit for the 2-class solution. AIC values were lowest in the 4-class solution, compared with the 1-, 2-, and 3-class solutions, indicating that the 4-class solution offered the better fit; however, the most notable change in AIC values occurred between the 1- and 2-class solutions. The silhouette coefficient was highest for the 2-class model (s = .50), indicating that the two classes were distinct from one another and generally densely packed, compared with classes in the 3- and 4-class solutions. Given that the 2-class solution provided the best fit of all models tested for BIC and revealed the most distinct clusters, the 2-class solution was retained as the best-fitting model. The cluster analysis identified no outlier cases.

Table 3. Model fit comparisons

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion, BIC = Bayesian information criterion. The best-fitting model is in bold.

Moral self-concept profiles

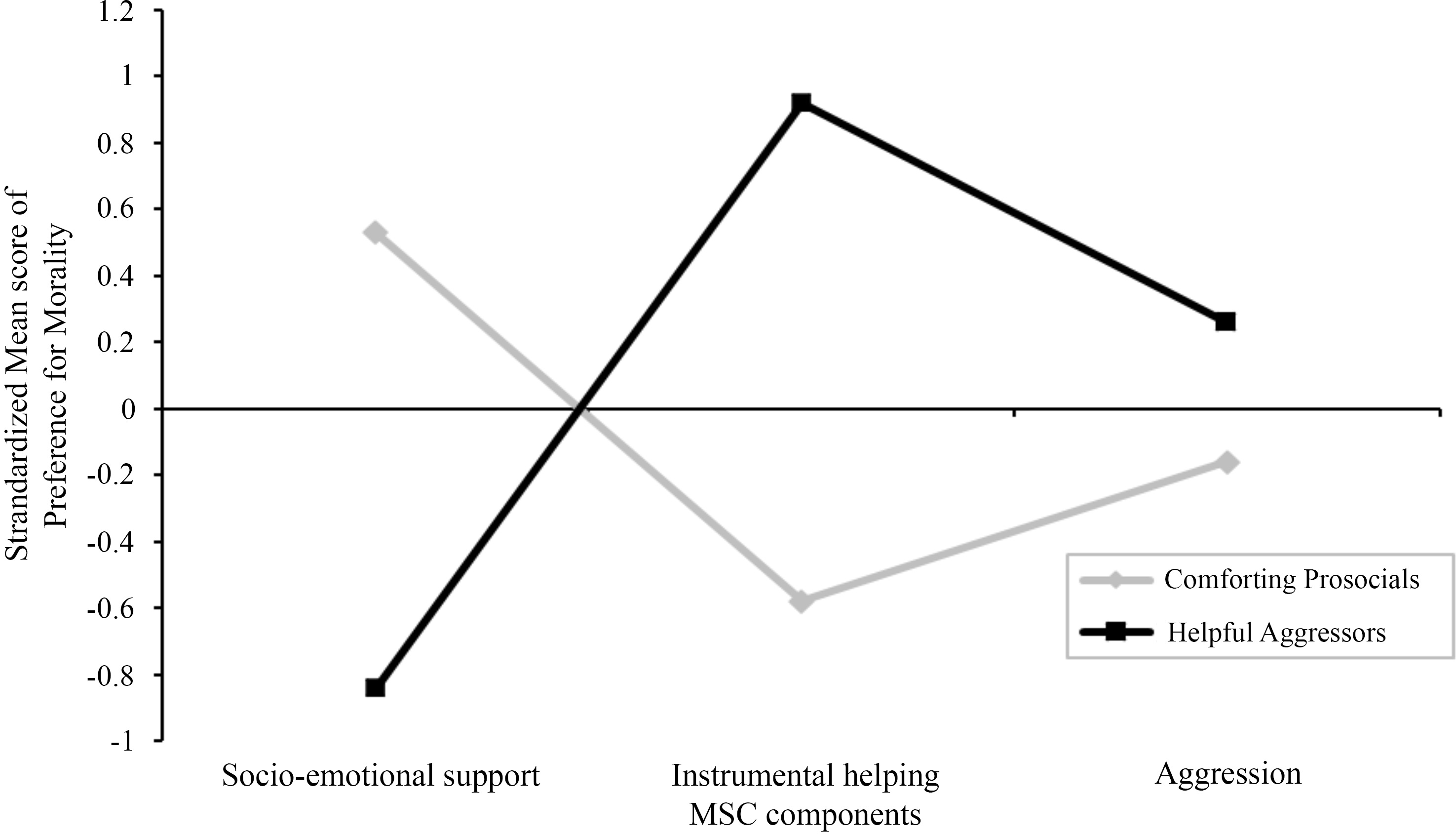

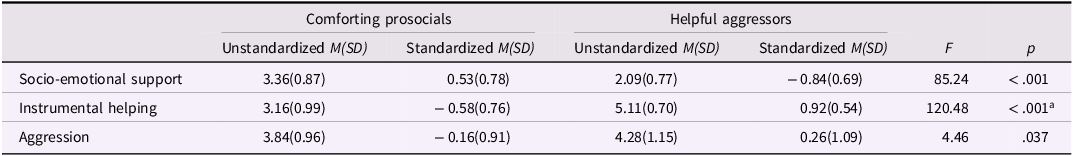

The two groups differed significantly across three MSC domains (see Table 4 for post hoc comparisons). The first cluster identified (n = 65, 61.3% of the sample) demonstrated a moderate preference for socio-emotional comfort and care (compared with the second cluster), a moderate aversion for instrumental helping, and a slight aversion to aggressive mores (see Table 4 for profile characteristics). For ease, we will refer to this group as the comforting prosocials. Figure 1 presents the two clusters based on parameter estimates of MSC variables.

Figure 1. Visual representation of cluster characteristics based on parameter estimates of MSC variables. MSC = moral self-concept.

Table 4. Profile characteristics

Note. M = median; SD = standard deviation. Values range from 1 to 6, with higher values indicating greater agreement with the respective concept and lower values indicating less agreement with the respective concept. a Due to significant Levene’s test indicating unequal variances, Dunnett’s test was used.

The second cluster of children (n = 41, 38.7% of the sample) were moderately aversive to providing socio-emotional comfort, strongly preferred providing instrument help, and slightly to moderately preferential aggressive mores, compared with the first cluster. Hereafter, we refer to this cluster as the helpful aggressors.

Associations between cluster membership and sociodemographic variables

We examined the possibility of differences in cluster membership by sociodemographic variables in order to determine relevant covariates. Using multinomial logistic regressions with typical demographic variables (i.e., gender, age, mother’s education, income, poverty threshold, and parents’ vocational preparedness), we found that the two clusters differed significantly in age (b = 0.116, SE = 0.044, Wald = 6.932, p = .008). Children in the comforting prosocials profile were approximately 6 months younger than children in the helpful aggressors profile (M = 50.73 vs. M = 56.01 months, respectively). No differences emerged for gender (X 2 (1, N = 106) = 0.994, p = .319), mother’s education (b = 0.093, SE = 0.188, Wald = 0.243, p = .622), poverty threshold (b = 0.311, SE = 0.763, Wald = 0.166, p = .684), income (b = 0.000, SE = 0.000, Wald = 0.094, p = .759), or parents’ vocational preparedness (b = 0.148, SE = 0.251, Wald = 0.3471, p = .556). Hence, children’s age was the only sociodemographic variable that was carried forward in further analyses.

Moral self-concept and moral behavior

Concurrent behavior

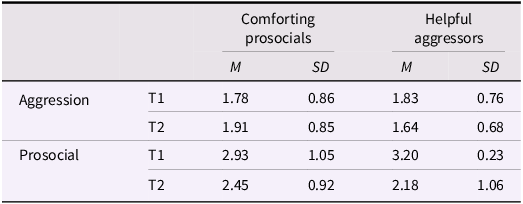

Comparing profiles of children’s MSC to concurrent (T1) teacher-reported behavior while controlling for age, the two groups did not differ in the amount of aggression or prosocial behavior (all p’s > .10; see Table 5 for descriptive statistics). Age did not meaningfully contribute to either model (η 2 = .001 and .000, respectively).

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of clusters based on teacher-reported behavior

Note. M = median; SD = standard deviation; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2.

Subsequent behavior

At Time 2, the two groups differed slightly in the amount of teacher-reported aggressive behavior (ηp 2 = .033, accounting for a small to medium amount of variance). Specifically, children in the comforting prosocials group displayed a greater amount of aggression than children in the helpful aggressors group (see Table 5). The two groups of children did not differ in the amount of prosocial behavior (ηp 2 = .015, p > .10).

Change in behavior over time

Children’s change in aggressive behavior over time between the two groups was significant, η 2 = .052, p = .018, with comforting prosocials increased overall (M change = 0.128, SD = 0.63) and helpful aggressors decreased overall (M change = -0.175, SD = 0.63). Age accounted for a small, non-significant amount of variance (η 2 = .004, p = .554). Lastly, the two groups differed in the change of prosocial behavior reported by teachers over time. Although they both decreased in prosocial behavior, the helpful aggressors group decreased more drastically compared with the comforting prosocials (η 2 = .033, p > .10; see Table 5), accounting for a small to medium amount of variance. Again, age did not meaningfully contribute to the model (η 2 = .000, p > .10).

Discussion

The MSC is suggested to play a key role in guiding moral behavior (Hardy & Carlo, Reference Hardy and Carlo2011; Kingsford et al., Reference Kingsford, Hawes and de Rosnay2018). Yet, no study to our knowledge has examined both prosocial and aggressive facets of the MSC using a person-centered approach, and very little is known about how multidimensional MSC relates to moral behavior in early childhood. In this study, we utilized a person-centered approach to identify patterns of MSC and then examined how these profiles explain moral behavior concurrently and 6 months later. Generally, our principal findings suggested two distinct clusters of MSC profiles (comforting prosocials and helpful aggressors), which predicted meaningful changes in both prosocial and aggressive behavior over time.

Profiles of the moral self-concept

Cluster analysis revealed two distinct MSC profiles. Consistent with our expectations, a “more moral” MSC group emerged, referred to here as comforting prosocials. Based on their responses to MSC items, these children were concerned about the physical and psychological well-being of others both in terms of promoting positive outcomes for others (e.g., comforting a sad friend) and reducing the harm they caused others. In other words, this group was high in empathy. Comforting prosocials did not seem particularly concerned with responding to others’ instrumental needs (e.g., helping clean up), which may suggest that they are more altruistic (McGinley et al., Reference McGinley, Pierotti and Carlo2022). Moreover, comforting prosocials expressed a disinclination toward aggressive motives, further supporting that young children generally view themselves as moral (Krettenauer et al., Reference Krettenauer, Campbell and Hertz2013).

It is important to note that children in the comforting prosocials group happened to be younger than the other group by about 6 months. We believe this age difference is meaningful in terms of both social and cognitive development. At this age, children may not have yet fully internalized the socialization required to ingrain helping behaviors as moral (Hao & Dong, Reference Hao and Dong2021; Malti et al., Reference Malti, Gummerum, Keller and Buchmann2009). Children at a younger age may be more sensitive to others’ negative emotions in social interactions, in that they are more likely and willing to comfort others when they feel sad or provide socio-emotional support (Spinard et al., Reference Spinard, Eisenberg, Sheffield Morris, Killen and Smetana2022). As they get older, their MSC development may expand to other, more conventional areas, including instrumental help. It is possible then that these children may therefore view helping as morally neutral or as serving a conventional need rather than a moral imperative and therefore may be less intrinsically motivated to help (Smetana, Reference Smetana, Killen and Smetana2006).

Moreover, the age difference between the two profiles likely corresponds with a difference in self-awareness or Theory of Mind, which could explain some of the differences in the two groups (i.e., the developmental collision of the coming-of-age of moral sense-making in conjunction with one’s views of the self). Evidence for the stability of well-off children’s (i.e., children of affluent, highly educated parents) consolidated views of the self suggests some stability beginning between ages 4 and 5 (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Lang and Schoppe-Sullivan2016), including the consolidation of the moral self (Strauß & Bondü, Reference Strauß and Bondü2023); however, to our knowledge, the stability of the self is untested in historically disinvested communities such as that examined here. It is possible that the material deprivation and psychological strain experienced by these families contribute to differences in the developmental timing of self-consolidation.

Additionally, it is worth noting that children do not necessarily need to perceive an item’s contents of the MSC as moral in order to receive a high score. That is to say, the MSC task does not ask children about the moral valence or value of a specific inclination (e.g., “Is it good or bad to help? Why?”). Instead, it asks children to report on their perceptions of their behaviors – a child may report feeling inclined to provide high levels of help, for instance, even if that child is helping out of a desire to comply with authority, rather than to benefit others. To our knowledge, this specific question is yet untested in the literature.

As anticipated, we also unveiled a group that indicated both prosocial and aggressive predispositions, whom we refer to as helpful aggressors. Children in this group displayed a pattern of moral tendencies in line with what Hawley (Reference Hawley2003) referred to as “bi-strategic controllers.” These children may feel motivated to hurt others but also suggest that they are good play partners and friends. These children were not motivated to preserve the psychological well-being of others through socio-emotional comfort but were motivated to engage in more overt prosocial behaviors (e.g., taking turns). Drawing from adult research on profiles of prosocial personalities (McGinley et al., Reference McGinley, Pierotti and Carlo2022), these individuals may have incorporated the expectations of caregivers and teachers (e.g., “Thank you for helping clean up, you’re a very good boy”) and have prioritized helping behavior as a result. These children also acknowledged a motivation to mildly harm peers, which is not atypical for this age group (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Vaillancourt, Barker, Nagin and Tremblay2007; Persson, Reference Persson2005; Vaillancourt et al., Reference Vaillancourt, Miller, Fagbemi, Côté and Tremblay2007) but bears further consideration. Children at this age are still developing their understanding of social expectations, communication skills, and learning to control impulses (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Menna, McAndrew and Johnson2021; Rademacher & Koglin, Reference Rademacher and Koglin2019; Ramsook et al., Reference Ramsook, Welsh and Bierman2020), and so to see aggressive proclivities is not surprising.

A reviewer also noted that there is an alternative interpretation of helpful aggressors’ behavior. Although helpful aggressors do see themselves more aggressively than comforting prosocials, as previously noted, some aggression is age-appropriate and may decrease with maturation (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Vaillancourt, Barker, Nagin and Tremblay2007). Based on Krettenauer’s (Reference Krettenauer2022) conceptual framework on moral motivation, helpful aggressors may be externally motivated to leave a good impression on others and to avoid leaving a negative impression. As prosocial behavior decreased over time, this group may therefore be prevention-oriented compared with promotion-oriented (Krettenauer, Reference Krettenauer2022), in that they may be more motivated to avoid a negative reputation (i.e., why we see decreases in aggression) rather than build a positive reputation (i.e., why we see decreases in prosociality). Neuroscientific evidence supports this; children who identify as less moral may also need to use less cognitive processes to anticipate scenes of aggression (e.g., hitting) than more moral children (Pletti et al., Reference Pletti, Decety and Paulus2022). By being able to anticipate aggressive actions better, these children may have the tools to anticipate and prevent aggressive actions.

Moral self-concept and behaviors

The two profiles of children predicted meaningful and impactful differences in behavior changes over the 6 months of data collection. The children that self-proclaimed their helpful and aggressive mores (i.e., helpful aggressors) actually showed a decrease in aggression, according to teachers, whereas the group that self-proclaimed their empathy (i.e., comforting prosocials) showed an increase in aggression. Additionally, both groups became less prosocial over time; however, the helpful aggressors did so more drastically.

As age did not meaningfully contribute to change in behavior for aggression or prosociality, these differences should be due to genuine differences between MSC profiles – that is, genuine differences in moral values – and are not resultant of developmental timing. Given that children in the comforting prosocials group perceive themselves as highly empathetic, and therefore highly concerned with others’ well-being, it is possible that these children engage in aggression to preserve the well-being of others (e.g., defending a friend from a bully). These children may have heightened justice sensitivity for others, which in older children tends to correspond with a stronger moral identity and heightened Theory of Mind (Strauß & Bondü, Reference Strauß and Bondü2022). Justice sensitivity refers to an intense response to perceived injustices and tends to correspond with several factors of moral development (Strauß & Bondü, Reference Strauß and Bondü2022). Children who demonstrate an altruistic justice sensitivity (i.e., justice sensitivity for others) versus children who prioritize justice for the self tend to focus more on equality of distribution, empathy, and sharing (Strauß & Bondü, Reference Strauß and Bondü2023). Here, although we did not test justice sensitivity, it is possible that these children – given their self-reported proclivities for prioritizing others’ emotional and general well-being – are hypervigilant when it comes to injustices toward their peers and use aggression as a morally sanctioned response (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Huang, Liu, Battista and Gahtan2024; Baker & Liu, Reference Baker and Liu2021; Jambon et al., Reference Jambon, Colasante, Peplak and Malti2018). In such cases, aggression is viewed as a moral imperative because it prioritizes the well-being of someone being victimized.

Although both groups reported high levels of prosocial motivations in their self-concept, these motivations differed drastically between the groups. In this sample, the preferences for comforting and instrumental helping were negatively related – suggesting that children may value one type of prosocial behavior over the other. One explanation could be that as children develop prosocial behaviors at different rates and express them to different degrees, children may prioritize using one strategy to support others (Dunfield et al., Reference Dunfield, Kuhlmeier, O’Connell and Kelley2011; Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, Reference Dunfield and Kuhlmeier2013; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2023). Additionally, the development of one type of prosocial behavior does not transfer to other types of prosocial behavior, meaning children may prioritize using and developing one type of prosocial behavior at a time (Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, Reference Dunfield and Kuhlmeier2013). In a classroom, it is likely that teachers equally value children who are helpful and children who comfort others or that teachers see no distinction between the two because both are types of prosocial behavior that are necessary for communal well-being. Unfortunately, the measures we used here to capture teacher-reported prosocial behavior did not fully reflect the difference found in MSC sub-types (e.g., the prosocial items on the PPRA did not correspond with specific items on the MSC). It is therefore difficult to detect differences in types of actual (teacher-reported) prosocial behavior – in other words, it is likely that the two profiles of children also differ in their actual prosocial behaviors (i.e., with one group being more empathetic and one being more helpful); however, we cannot test this using the current measures. Moreover, based on the correlations, it is possible that prosocial behavior is less stable over time (compared with aggression), which may be why we did not detect differences of prosocial behavior between groups at Time 1 or Time 2.

Additionally, proactive and reactive aggression were highly correlated, which is a common finding in research on aggression (e.g., Baker et al., Reference Baker, Huang, Battista and Liu2023; Evans et al., Reference Evans, Frazer, Blossom and Fite2019; Jambon & Smetana, Reference Jambon and Smetana2018; Xu & Zhang, Reference Xu and Zhang2008). Although they are related and may co-occur, meta-analytic evidence suggests that proactive and reactive aggression are different (Polman et al., Reference Polman, Orobio de Castro, Koops, van Boxtel and Merk2007). Additionally, neurological evidence indicates that there are structural differences in brain volume between proactive and reactive aggressors (Naaijen et al., Reference Naaijen, Mulder, Ilbegi, de Bruijn, Kleine-Deters, Dietrich, Hoekstra, Marsman, Aggensteiner, Holz, Boettinger, Baumeister, Banaschewski, Saam, M E Schulze, Santosh, Sagar-Ouriaghli, Mastroianni, Castro Fornieles, Bargallo, Rosa, Arango, Penzol, Werhahn, Walitza, Brandeis, Glennon, Franke, Zwiers and Buitelaar2020; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Joshi, Jahanshad, Thompson and Baker2017). Therefore, although highly correlated, sufficient evidence from numerous disciplines points to a divergence of constructs. It is also possible that the length of the teacher-child relationship explains the correlation between proactive and reactive aggression. At the initial time of the assessment, students were in their preschool classroom for a shorter time frame than during the second assessment. Hence, teachers possibly had less familiarity with children’s behavior during the initial assessment.

Moreover, a reviewer noted that prosociality and aggression were positively correlated here, which is uncommon. Upon further reflection of the items in the prosocial scale, we believe this finding is due to the items reflecting self-serving prosociality (Persson, Reference Persson2005). That is, across various types of prosocial behavior (e.g., self-serving prosociality, “This child will often share with others, to get what s/he wants” used here in the PPRA, compared with altruistic prosociality, such as helping in response to a peer’s distress), prosocial behavior which serves the self is commonly positively correlated with both reactive and aggressive behavior, particularly in younger preschool-age children (Persson, Reference Persson2005).

Limitations and future directions

This study provides preliminary insights into patterns of MSC and their relation to moral behavior. However, a few limitations should be noted. First, our sample size is rather small, which does impact our statistical techniques. Although we are not aware of an a priori power analysis approach suitable for person-centered approaches, our study benefits from having a relatively low number of indicators, few classes, and clear distinctions between classes, which makes modeling with a smaller sample easier (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Reference Nylund-Gibson and Choi2018). Moreover, the critical issues with small sample sizes and person-centered approaches (i.e., poor fit indices and lack of model convergence; Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Reference Nylund-Gibson and Choi2018) were not issues here.

Second, this study focused on teacher’s reports of moral behaviors. Teachers only interact with children at school. Their reports may not capture all nuances of behavior as children may behave differently at home and school (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Ostrov, Murray-Close, Blakely-McClure, Kiefer, DeJesus-Rodriguez and Wesolowski2021). Therefore, teacher reports of student’s behaviors are context specific, and their reports may be unable to capture all aspects of a child’s prosocial and aggressive behavior.

Also, the age group of the current study includes younger children (3 years old) than the age range (4–6 years old) typically used for this interview (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2021, Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2023), although it has been used with children this young previously (Baker & Woodward, Reference Baker and Woodward2023). Young children might interpret the interview differently than older children. In addition, we only measured explicit MSC. Some may argue that we should have used the implicit MSC; however, prior research suggests that the implicit MSC may not be appropriate for children this young, as young children may still be building internal consistency (Christner et al., Reference Christner, Pletti and Paulus2020; Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021). Lastly, as our focus was on aggressive behaviors and not prosocial facets, the teacher-report measure did not allow us to parse specific aspects of prosocial behavior; a study on this topic would be interesting and would nicely add to the present body of work in this topic (e.g., Sticker et al., Reference Sticker, Christner, Pletti and Paulus2021, Reference Sticker, Christner, Gniewosz, Pletti and Paulus2023).

Conclusion

This study provides a preliminary understanding of patterns of the MSC and their relations to moral behavior in early childhood. Our findings show that patterns of MSC in early childhood may inform children’s future moral behavior. Additionally, by considering prosocial and aggressive dimensions of moral inclinations, we were able to gain insights into how moral inclinations may inform behavior over time. Our findings suggest that children’s multidimensional profiles of MSC help predict later moral behavior and behavioral changes over time in early childhood.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579424000993.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the work by our undergraduate research team for their work in data collection. We are indebted to the children, families, teachers, and schools who participated in this project.

Funding statement

None.

Competing interests

None.