In the late twentieth century, international relations scholars turned their attention to the increasingly prominent transnational advocacy networks (TANs). These networks bring together various state and nonstate actors that share common ideas, values, discourses, and information. They advocate through transnational campaigns, flexibly toggling between various strategies and tactics. Across the Global South, TAN campaigns often aim to socialize targeted states to new norms of behavior, such as the defense of human rights (Burgerman Reference Burgerman1998; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Lerche Reference Lerche2008), environmental protection (Wu Reference Wu2013; Sierra and Hochstetler Reference Sierra and Hochstetler2017; Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, Jonathan Kishen Gamu, Athayde, Regina da Cal Seixas and Viola2019), or, as this article highlights, anticorruption (Galtung Reference Galtung2000; McCoy Reference McCoy2001).

Recent contributions have revised and refined the TAN literature’s central arguments. One group of scholars explores why only certain issue areas, shared norms, and local movements foster TAN mobilization (Bob Reference Bob2001; Carpenter Reference Carpenter2007; Moog Rodrigues 2016). A second group questions the idealized portrayal of TANs as representative (Dryzek Reference Dryzek2012; Pallas Reference Pallas2017; Norman Reference Norman2017), collaborative (Liu Reference Liu2006; Bownas Reference Bownas2017), and motivated solely by normative concerns (Noakes Reference Noakes2012; Prakash and Gugerty 2010). These researchers further note the limitations of Keck and Reference SikkinkSikkink’s 1998 “boomerang pattern” (e.g., Matejova et al. Reference Matejova, Parker and Dauvergne2018) and broaden the range of available TAN strategies and tactics (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002; Andonova and Tuta Reference Andonova and Tuta2014; Wu Reference Wu2013; Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, Jonathan Kishen Gamu, Athayde, Regina da Cal Seixas and Viola2019).Footnote 1

A third group of scholars challenges the original literature’s expectation of ascendant nonstate actors in a world of declining national states (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2005; Smith and Weist 2005; Sending and Neumann Reference Sending and Neumann2006; Risse Reference Risse2007). Several recognize TANs’ dependence on, and collaboration with, rich states (Huelshoff and Kiel Reference Huelshoff and Kiel2012; Bassano Reference Bassano2014; Andonova Reference Andonova2014). Others underscore the obstacles that closed domestic and international political opportunity structures may pose to TAN norm socialization (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2005; Reference SikkinkSikkink 2003; Princen and Kerremans 2009; Ayoub Reference Ayoub2013; Sierra and Hochstetler Reference Sierra and Hochstetler2017).

This article’s argument approaches this latter issue by addressing Global South states’ efforts to forestall TAN initiatives to diffuse norms. To be sure, a growing stream of work critical of the optimism of conventional TAN research suggests that even weak, vulnerable states may successfully subdue activist challenges (Christensen and Weinstein Reference Christensen and Weinstein2013; Zwingel Reference Zwingel2012; Dupuy et al. Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2015, Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2016; Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez Reference Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez2018). At the same time, these more recent contributions fail to probe how states devise the strategy and content of their anti-TAN responses. This article elucidates the contentious process of learning through which states devise policies and instruments to resist TAN norm socialization campaigns.

The Guatemalan state’s distinct responses to two consecutive legal-political challenges, undertaken in the context of a single, high-profile anticorruption TAN campaign, illustrate the argument. The United Nations International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (Comisión Internacional contra la Impunidad en Guatemala, CICIG) and the Guatemalan Attorney General’s Office (AGO) led this TAN campaign, which unfolded between 2015 and 2019. These two core organizations collaborated closely with NGOs, Guatemalan government agencies, media outlets, churches, universities, foundations, public intellectuals, powerful northern states, and a multiclass social movement.

In both the legal-political challenges studied, this anticorruption TAN combined “managerial” and “enforcement” strategies (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002; Zwingel Reference Zwingel2012; Andonova and Tuta Reference Andonova and Tuta2014) to prosecute sitting Guatemalan presidents and associates accused of corruption. Yet despite their common approach, the two challenges produced contrasting outcomes. In 2015, the first challenge, known as The Line (La Linea), succeeded in forcing the resignation of President Otto Pérez Molina (Reference Molina2012— 15) and his incarceration, alongside several cabinet members and business leaders. The second legal-political challenge, named Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN (Financiamiento Electoral Ilícito—FCN), targeted Pérez Molina’s successor, Jimmy Morales (2016—20), and his government in 2017. But despite its parallels with 2015, this latter challenge neither removed the president from office nor accelerated the desired behavioral changes in the Guatemalan state. Instead, it spurred a decisive state response that swiftly dismantled the TAN.

This article builds on the state-centered policy-learning literature to account for the divergent outcomes of the 2015 and 2017 legal-political challenges in Guatemala (Hall Reference Hall1993; Campbell Reference Campbell1998; Hay Reference Hay, John and Ove2001; Mehta Reference Mehta, Beland and Cox2010; Berman Reference Berman2013). As does recent TAN research, it suggests that the shifting responses to unfolding campaigns by even fragile states may forestall TAN norm socialization initiatives. Yet it further argues that the content of those targeted states’ responses can neither be taken for granted nor assumed to be the result of calculations that only consider the costs of a possible international backlash. Instead, states may engage in context-specific processes of policy learning that shape the domestic security policy paradigms they deploy to undermine TAN cohesion, strategies, and tactics.

Given this argument, the empirical material details how two different domestic security policy paradigms framed the divergent Guatemalan state responses in 2015 and 2017: Pérez Molina’s “Iron Fist” and Morales’s “Guatemala First.” These two paradigms were forged through dissimilar patterns of policy learning among government officials before the TAN legal-political challenges. Pérez Molina’s Iron Fist paradigm had emerged to grapple with an unprecedented crime wave in the late 2000s. It favored a hardline approach against unlawful activity that proved ill-suited even to conceive of the TAN as an issue relevant to domestic security in 2015. By contrast, Morales’s Guatemala First alternative arose in the mid-to-late 2010s, as the TAN campaign reached the pinnacle of its influence. It drew on the arguments of officials and business leaders, many of them accused of corruption, who persuasively recast the TAN as Guatemala’s overriding domestic security threat. Abetted by two facilitating conditions—the TAN’s “strategic inertia” and declining US government support for the campaign—the deployment of this latter paradigm effectively subverted the anticorruption norm socialization process.

To develop this argument, the rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section describes the two anticorruption TAN legal-political challenges in Guatemala. Section 3 addresses the relevant literature, problematizing emerging descriptions of anti-TAN state responses and proposing the alternative policy-learning perspective. Section 4 applies the perspective to the Guatemalan state’s differing responses to the two legal-political challenges. The concluding section explores some of the argument’s implications.

The Anticorruption TAN Legal-Political Challenges

The anticorruption TAN campaign in Guatemala unfolded between 2015 and 2019. Led by a unique UN agency, the CICIG, and by the Guatemalan Attorney General’s Office (AGO), the TAN brought together a broad range of actors, including domestic and international NGOs and foundations (e.g., the Washington Office for Latin America, Human Rights Watch, the Soros Foundation, the Myrna Mack Foundation), student and religious organizations, smaller political parties, public intellectuals, business leaders, media outlets, and a diverse social movement. International donors, most notably the United States and Sweden, also lent their support, as did the directors of a few Guatemalan government agencies, such as the Tax Collection Agency and the Interior Ministry (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2016; Weld Reference Weld2016; Krylova Reference Krylova2018; Call and Hallock Reference Call and Hallock2020).

As part of its campaign to socialize the Guatemalan state to the anticorruption norm, the TAN launched two high-profile legal-political challenges, The Line in 2015 and Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN in 2017. These challenges respectively targeted the governments of Presidents Pérez Molina and Morales. In both, the TAN relied on the same combination of “managerial” and “enforcement” strategies. Managerial strategies involve the use of resources and novel information to frame, persuade, and enhance “the capacity of public administrations and civil society actors to interpret and apply international rules” (Andonova and Tuta Reference Andonova and Tuta2014, 779). In this vein, the Guatemalan TAN collaborated closely with allied Guatemalan government offices, such as the Tax Collection Agency, to gather information and build up legal cases. To educate the public on the campaign and specific challenges, CICIG commissioner Iván Velásquez, Guatemalan attorney general Thelma Aldana, and their staffs also organized several media activities and meetings with relevant actors.

Alongside that managerial strategy, the TAN embraced “enforcement” mechanisms (Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002; Andonova and Tuta Reference Andonova and Tuta2014). Most prominently, the CICIG and AGO pursued legal prosecutions. As part of The Line, they charged not only President Pérez Molina but also his vice president and numerous government officials and business leaders. Similarly, in the Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN case of 2017, they formally accused President Morales, key congress members, and campaign organizers of his FCN party, as well as the patriarchs of some of Guatemala’s most influential business groups.

Yet the anticorruption TAN’s enforcement strategy incorporated other notable tactics. Domestically, the managerial strategy’s public education campaign activated mass protests to exert pressure on the targeted governments. In August 2015 and again in August 2017, more than one hundred thousand people rallied in Guatemala City’s Central Plaza to demand Presidents Pérez Molina and Morales’s resignations after the TAN formally charged them. National economic strikes, through which a significant share of businesses paused their activities, followed those protests. Internationally, the TAN relied on more conventional boomerang politics to “name and shame” the Pérez Molina and Morales administrations and tarnish their international reputation. Motivated by the unfolding campaign, representatives from powerful North American and European governments, multilateral agencies, and NGOs demanded that the presidents and their associates submit to the rule of law.

In their initial phases, The Line and the Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN legalpolitical challenges followed similar paths. In both, an exodus of high-ranking government officials severely weakened the executive branch shortly after the mass protests.Footnote 2 In parallel, the legal cases against the presidents moved quickly through the different administrative stages. In each, it took less than 20 days after Commissioner Velasquez and Attorney General Aldana presented their charges for the country’s Supreme Court to allow an inquiry in Congress and for Congress to vote on whether to remove the president’s immunity and force him to stand trial.

However, at this point, the cases diverged. In September 2015, Congress unanimously voted to strip Pérez Molina of his immunity, forcing him to resign and face prosecution. For Morales, that final step differed: after 85 percent of congressional representatives (133 out of 158) either abstained or voted against removing his immunity, a surge of popular mobilization and international pressure forced a second poll ten days later. But even then, less than 45 percent of congressional representatives (70 out of 158) favored removing Morales’s immunity. He would therefore avoid the courts, retain the presidency, and, over the next two years, use the state to decisively defeat the anticorruption TAN.

This outcome is remarkable insofar as in 2017, relative to 2015, the TAN seemed poised to benefit from a more propitious domestic political opportunity structure. The Morales administration’s vulnerability to the challenge appeared to significantly exceed Pérez Molina’s. Unlike Pérez Molina, who had held various high-level executive and legislative positions, Morales was a political neophyte with no government experience. And in contrast to Pérez Molina’s Partido Patriota (PP), which was a major force in Congress throughout the 2000s and held the majority of seats during his presidency, Morales’s Frente de Convergencia Nacional (FCN) represented only the fifth-largest legislative delegation after the 2015 election.

Furthermore, the TAN entered the 2017 challenge in a seemingly stronger domestic position than in 2015. Its resources, access to information, and institutional capacity significantly expanded after 2015, as the TAN gained domestic and international recognition for its successful Line challenge against Pérez Molina’s administration.Footnote 3 With success also came enhanced network density and leverage, as organizations prioritizing the anticorruption agenda joined in support. Additional backing came from the public, with more than 70 percent of the population expressing support for the TAN in the aftermath of The Line.

If neither the targets’ apparent vulnerability nor the TAN’s ostensible strength provides a compelling explanation, we may begin to account for the divergence in the outcomes of the two legal-political challenges by examining two facilitating conditions. The first involves the TAN’s changing international political opportunities. As prior work notes, while TANs often depend on support from influential northern states, such foreign backing may wax and wane (Huelshoff and Kiel Reference Huelshoff and Kiel2012). Consistent with that observation, the Guatemalan anticorruption TAN lost a significant source of leverage following the 2017 Obama-Trump transition in the United States, as the executive and legislative branches’ commitment to the campaign withered.

However, at least three observations suggest that this US transfer of power is insufficient to account for the contrasting challenge outcomes. First, while the Trump administration and several Republican senators eventually turned their backs on the anticorruption TAN, the shift occurred gradually. Indeed, following the CICIG and AGO’s presentation of the Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN legalpolitical challenge in 2017, the US State Department, through its ambassador, expressed its unwavering support for the anticorruption campaign.Footnote 4 Second, while international pressure through the boomerang pattern constituted a prominent tactic for the anticorruption TAN, other managerial and enforcement alternatives, such as domestic mobilization or collaboration with select stage agencies, were equally important. The political changes in the United States affected none of these additional tactics.

Third, scholars have long recognized that though structural changes may restrict some opportunities, TANs enjoy remarkable entrepreneurial ability to adapt and find new options (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2005; Reference SikkinkSikkink 2003; Princen and Kerremans 2009; Bassano Reference Bassano2014; Norman Reference Norman2017). Research further shows that TANs’ adaptation to these changes is contingent on access to resources and information (Hale Reference Hale2020), high levels of professionalization (Norman Reference Norman2017; Andonova Reference Andonova2014), and broad network ties (Bownas Reference Bownas2017)—all features abundant in the Guatemalan anticorruption TAN.

Yet the TAN in Guatemala failed to exploit that potential flexibility to devise new tactics. During the 2015 Line legal-political challenge, the TAN’s managerial and enforcement strategies had offered a dramatic break from past civil society practices, surprising state authorities and delivering remarkable success. Nevertheless, during the 2017 Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN legal-political challenge, the TAN neglected to update its repertoire of tactics in any meaningful way. Instead, it resorted to the same managerial tactics of education and collaboration with public sector and civil society allies, alongside enforcement involving legal cases, as well as domestic and international pressures. Though it did not deterministically spur the TAN’s failure, this “strategic inertia” rendered its tactics predictable to state officials. It therefore constitutes the second facilitating condition for the divergence in the outcomes of the two legal-political challenges.

In sum, flagging US government support and unchanging TAN strategy after the 2015 Line challenge set the stage for the unexpected failure of the 2017 Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN challenge. At the same time, neither of those conditions ensured that, unlike Pérez Molina, Morales would retain the presidency. Nor do they explain why a once-celebrated TAN anticorruption campaign collapsed two years later. Instead, to understand the divergent outcomes of the two legal-political challenges, this article turns to the processes of policy learning and paradigm adoption that occurred within the Guatemalan state. It suggests that, in the context of those two facilitating conditions, the Guatemalan state under Morales devised and deployed a distinct anti-TAN response that, departing from Pérez Molina’s, proved effective in undermining the TAN campaign.

TANs, Norm Socialization, and the Role of the State

The conventional TAN literature arose partly in response to realist arguments on norm emergence and diffusion. Whereas realist explanations privilege hegemonic actors and material understandings of power, the constructivism of the TAN literature underscores the role of nonstate actors driven by shared principled ideas and values (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Risse Reference Risse2007; Noakes Reference Noakes2012; Dryzek Reference Dryzek2012). Much of the TAN literature further embraces the “norm life cycle model,” according to which norms initially gain a foothold in the Global North and then “cascade” to become institutionalized around the world (Reference Finnemore and SikkinkFinnemore and Sikkink Reference Sikkink1998). TANs thereby act as norm entrepreneurs in their interactions with Global North states and international organizations (Risse Reference Risse2007) and as agents of norm socialization across the Global South (Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Zwingel Reference Zwingel2012; Martín de Almagro Reference Martín de Almagro2018).

Empirically, while the bulk of this latter Global South-focused research centers on how TANs socialize targeted states to human rights (Burgermann 1998; Keck and Sikkink Reference Keck and Sikkink1998; Lerche Reference Lerche2008; Bassano Reference Bassano2014) and environmental protection norms (Wu Reference Wu2013; Sierra and Hochstetler Reference Sierra and Hochstetler2017; Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, Jonathan Kishen Gamu, Athayde, Regina da Cal Seixas and Viola2019), a few authors have also addressed the anticorruption norm (Galtung Reference Galtung2000; McCoy Reference McCoy2001). For example, McCoy adopts a constructivist perspective that privileges the role of a changing global environment of increased democracy, emerging social interactions, and a flourishing civil society in driving the institutionalization of the anticorruption norm in the 1990s. As those authors claim, governmental and nongovernmental organizations and networks (e.g., Transparency International, TANs) leveraged those global changes to raise awareness, institutionalize the norm, and foster its acceptance by the vast majority of relevant actors.

Through this type of argument, the TAN literature’s constructivist approach productively reveals the salience of these normatively driven networks and nonstate actors. Yet its original opposition to realist assumptions often also implies zero-sum state-society relations, in which strengthened nonstate actors erode state authority and power (Smith and Wiest Reference Smith and Wiest2005; Sending and Neumann Reference Sending and Neumann2006; Dupuy et al. Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2015). The literature therefore tends to downplay the role of states in TAN-led norm socialization campaigns. Indeed, as Risse (Reference Risse2007) notes early on, while “most empirical work on transnational actors” prioritized their impact “on interstate relations, international organizations, and international institutions in general,” it offered little insight “about states and IOs enabling and/or constraining TNA activities” (258).

More recent work addresses some of these gaps. On the one hand, some evidence points to collaborative relations between states and TANs. That Global North states may support TANs is not surprising. The foundational boomerang pattern presupposed those partnerships, and early research showed that TANs “often perform tasks which states and international organizations either cannot or do not want to carry out” (Risse Reference Risse2007, 260). However, even in the Global South, scholars have found examples of state agencies forging alliances with NGOs and TANs (Wu Reference Wu2013; Kauffman and Martin Reference Kauffman and Martin2014).

On the other hand, research also shows that targeted Global South states may forcefully respond against, and effectively constrain, TAN-led norm socialization campaigns. Building on a long line of work on political opportunity structures (Meyer Reference Meyer2004; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2005; Reference SikkinkSikkink 2003; Princen and Kerremans 2009; Ayoub Reference Ayoub2013; Sierra and Hochstetler Reference Sierra and Hochstetler2017), most of this work reveals the prevalence of such state-devised campaign obstacles in larger Global South countries, such as China (Wu Reference Wu2013; Noakes Reference Noakes2012), India (Lerche Reference Lerche2008; Matejova et al. Reference Matejova, Parker and Dauvergne2018), and Brazil (Moog Rodrigues 2016; Sierra and Hochstetler Reference Sierra and Hochstetler2017; Moreira et al. Reference Moreira, Jonathan Kishen Gamu, Athayde, Regina da Cal Seixas and Viola2019). However, growing evidence illustrates the effective response capacity of even vulnerable, weaker, and poorer states (Christensen and Weinstein Reference Christensen and Weinstein2013; Dupuy et al. Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2015, Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2016; Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez Reference Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez2018). For instance, Dupuy et al. (Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2015) explore the Ethiopian state’s 2009 ban on foreign funding, directed at NGOs working on salient TAN normative concerns, such as human rights, democracy, and ethnic relations. They conclude that “even the feeblest of governments can disrupt NGO operations” (422).

This emerging stream of work goes some way toward remedying the TAN literature’s faulty expectation that an ascendant transnational civil society would eclipse state authority. However, beyond cost-benefit assessments of state-level actions that emphasize the risk of foreign backlash (Christensen and Weinstein Reference Christensen and Weinstein2013), this work offers limited theorizing on the process of state response definition. That is, it lacks a clear understanding of how states settle on the strategy and the content of their anti-TAN response.

There are reasons to address these issues more systematically. For one, the documented menu of tools available in the “populist playbook” is long and growing, with no evident optimal mix of response policies (Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez Reference Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez2018). Furthermore, a vast, multidisciplinary scholarship has long challenged the rational choice policymaking approach that currently undergirds much of this emerging work.Footnote 5 It therefore stands to reason that researchers interested in TANs in the Global South can refine their arguments by elaborating a more robust, contextualized account of the process through which even weak, vulnerable states devise their responses to transnational campaigns.

The Argument: Policy Learning by Targeted States

The policy-learning perspective portrays states as capable of assessing the results of past policies and adjusting their understandings and future policies accordingly (Hall Reference Hall1993; Campbell Reference Campbell1998; Hay Reference Hay, John and Ove2001; Mehta Reference Mehta, Beland and Cox2010; Berman Reference Berman2013). This perspective assumes that under most circumstances, a dominant “policy paradigm” prevails in each field of state policy. While most of this work centers on the field of macroeconomic management (Hall Reference Hall1993; Hay Reference Hay, John and Ove2001), the approach has also been applied to the fields of education (Mehta Reference Mehta, Beland and Cox2010), health (Reference NoyNoy 2017), defense and foreign policy (Legro Reference Legro2000; Goldstein and Keohane 1993), and industrial policy (Reference SikkinkSikkink 1991; Reference AdlerAdler 1989). In each of these fields, dominant paradigms, advanced and implemented by actors within the state, define the overarching goals and problems prioritized by policy and provide relevant policy instruments (Hall Reference Hall1993; Mehta Reference Mehta, Beland and Cox2010).

Given this general understanding of policymaking, the literature focuses on explaining periods of “third-order” change (Hall Reference Hall1993), when states “learn” and replace one policy paradigm for another. According to the literature’s conventional view, these times of transition begin with anomalies, or contradictions, that defy the assumptions and explanations of the dominant paradigm. The challenge that those anomalies pose to the field’s goals is beyond doubt, and their emergence thereby erodes the legitimacy of a dominant paradigm’s policies. As those anomalies accumulate, they trigger ad hoc and experimental responses by policymakers, which stretch the intellectual coherence of the regnant paradigm. They also produce contested and polarizing public debates, especially when ad hoc responses fail. Eventually, those accumulated anomalies, failures, and debates culminate in moments of crisis, when the authority of the dominant paradigm fades (Hall Reference Hall1993; Berman Reference Berman2013).

However, which policy paradigm arises as a suitable replacement depends as much on the alternative accounts available as on the characteristics of the anomalies and policy failures themselves. Those alternative accounts, embraced by rival coalitions competing for power, convey distinct understandings of the causes of the crisis. They advance policy goals and instruments consistent with those understandings. The account that eventually prevails to become the new regnant paradigm is partly determined by content persuasiveness (Schmidt Reference Schmidt2008). Nevertheless, a triumphant account also depends on the influence of its backers, who disseminate the ideas, recruit effective allies, and most generally, position that distinct understanding in the public consciousness (Hall Reference Hall1993; Berman Reference Berman2013). Once in place, a victorious policy paradigm redefines the central problems and goals that guide a field’s policy, replaces the prevailing policy instruments, and empowers new actors within the state.

Policy Learning in the Field of Domestic Security

This article draws on the policy-learning perspective to account for targeted states’ development of anti-TAN responses. It suggests that those responses are shaped by dominant policy paradigms in the field of domestic security. In this field, states devise their approach to maintain order, exert control over their population, apply the law, and foreclose threats to their authority.Footnote 6 Domestic security policy paradigms guide that approach by identifying the field’s overarching problems and goals, usually pertaining to social ills such as homicides, crime, and drug trafficking. They also supply coherent policy responses, whether focused on prevention, repression, or rehabilitation.

At the same time, the proposed argument follows Hay (Reference Hay, John and Ove2001) in offering a subtle modification to the policy-learning literature’s assumptions about the crises precipitating the third-order change. As the foregoing discussion describes it, the conventional view assumes that anomalies and policy failures that cast doubt on dominant paradigms are easily recognizable. That is to say, it takes for granted that the presence of a crisis is indisputable. Debates among rival coalitions are thus limited to different diagnoses for those crises and especially to proposed replacement paradigms.

By contrast, this article suggests that in the domestic security policy field, the extent to which unfolding events are conceived as anomalies is itself subject to debate.Footnote 7 From this latter perspective, rival coalitions not only offer distinct understandings of the causes of what is widely assumed to be a crisis. They also craft “narrations of crisis” (Hay Reference Hay, John and Ove2001), which are designed to persuasively argue that certain events constitute undeniable challenges to the field’s policy priorities. In other words, these coalitions engage in projects of crisis construction even before they propose solutions.

That subtle modification explains why TAN campaigns, which often advocate the fair application of internationally recognized norms, may themselves come to be conceived as overriding domestic security challenges. Many times, targeted state officials and their allies conclude that, rather than norm deviance, it is the TANs’ managerial and enforcement strategies that threaten their authority, capacity to maintain order, and control over the population. However, these officials and their allies’ conclusion may run counter to the broader consensus. That is clear in anticorruption TAN campaigns, which often disclose evidence of nefarious actions ascribed to the highest echelons of the state hierarchy. Those disclosures, while challenging the state hierarchy’s position, often also enjoy some level of public support.

Under these conditions of disagreement regarding the relevance of TAN actions for the field of domestic security, targeted officials and their allies must make the case that TAN tactics indeed constitute conspicuous domestic security anomalies, rather than welcome contributions to the enforcement of the law. Put differently, they must construct and disseminate a compelling “narration of crisis.” Only after their effective execution of this project of crisis construction may these officials and their allies promote a new paradigm which positions the TAN as the overriding domestic security threat. The rest of this article explores this argument in the context of Guatemala’s high-profile anticorruption campaign.

State Policy Learning and the Anticorruption TAN Campaign in Guatemala

To establish the proposed theoretical contribution and explain the unexpected divergence in the outcomes of the anticorruption TAN’s two legal-political challenges, this section compares the Guatemalan state’s policy-learning processes and anti-TAN responses in 2015 and 2017. Figure 1 depicts the historical review, which contrasts the domestic security anomalies as defined by the emerging “narrations of crisis” (Hay Reference Hay, John and Ove2001) that prevailed in Guatemala before each legal-political challenge. Those anomalies and narrations, unique to each period, shaped the divergent patterns of state-level policy learning. They delivered two distinct domestic security policy paradigms: an Iron Fist paradigm under Pérez Molina’s government and a Guatemala First one under Morales. These governments then deployed their distinct regnant paradigms in response to the twin anticorruption legal-political challenges, with opposing results.

Figure 1. Influence of Targeted Governments’ Domestic Security Policy Paradigms on the Outcome of TAN Legal-Political Challenges

2015: The Anticorruption TAN’s Legal-Political Challenge to the Pérez Molina Administration

The Pérez Molina administration faced the 2015 TAN legal-political challenge with an Iron Fist domestic security paradigm. That paradigm had become dominant a few years earlier, in a context marked by increasing concerns over violent crime. Soaring homicides partly drove the growing unease (Krause Reference Krause2014; Brockett Reference Brockett2019). However, the emphasis placed on the anomalous accumulation of those incidents by two increasingly influential narrations of crisis exacerbated the uncertainty.

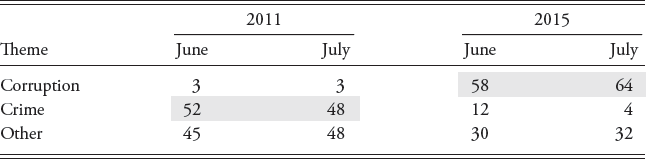

Both narrations of crisis regarded the dominant “peacebuilding” domestic security paradigm that prevailed in the early 2000s with skepticism.Footnote 8 They faulted its failed ad hoc responses to the crime wave and called for a change in the policy field’s prioritized problems, goals, and solutions.Footnote 9 They also attracted widespread media attention. In fact, as table 1 shows, violent crime accounted for the highest share of front-page stories in Guatemala’s leading newspaper, Prensa Libre, during June and July 2011, just a few months before Pérez Molina’s election in late 2011.

Table 1. Contrasting Overriding Problems: Share of Front-Page Stories in Prensa Libre (percent)

Source: Author

Yet despite their shared emphasis on the crime wave as an anomaly and their opposition to the peacebuilding paradigm, those competing narrations of crisis differed in their coalition of backers, diagnoses, and favored policy responses. The first drew most of its support from conservative business, political, and military elites. It decried the individual deviance of ostensibly identifiable criminals and denounced the alleged absence of punitive measures to repress them (Krause Reference Krause2014; Holland Reference Holland2013). For its part, the second narrative, favored by human rights organizations and progressive political actors, explained the incidents by reference to poverty, inequality, and inadequate state social support in marginalized communities (Azpuru Reference Azpuru2008; Krause Reference Krause2014). Though both narrations of crisis would influence policymaking during the late 2000s and early 2010s, it was the former that, with Pérez Molina’s election in 2012, informed an ascendant Iron Fist paradigm.

As Holland (Reference Holland2013) explains, iron fist approaches usually suspend procedural rights, involve the military in policing, and introduce discretionary crimes that allow security forces to sweep poor neighborhoods. Those three elements found an enthusiastic advocate in Pérez Molina. During his presidency, he concentrated decisionmaking authority in the Interior and Defense Ministries at the expense of the judicial system, AGO, and social development agencies. He relied on repressive domestic security instruments to target alleged gang members and drug traffickers in poverty-stricken urban areas, often with little accountability. And he praised the substantial increases in the Iron Fist paradigm’s prized indicators, such as the number of arrests (Pérez Molina Reference Molina2012).

However, while Pérez Molina’s Iron Fist paradigm accomplished its crime-centered imperatives, it could only muster an unplanned and ineffective response to the TAN legal-political challenge of 2015. That challenge began with an April 16 press conference, in which CICIG commissioner Velasquez and AGO Anti-Impunity Section director Oscar Schaad presented the first phase of an ongoing corruption investigation christened The Line. Revealing compelling evidence, they charged 20 individuals in relation to a scheme to funnel resources out of Guatemalan customs.

Among them were Pérez Molina’s two most recent directors of the tax collection agency and the vice president’s private secretary.

Over the next six months, the TAN combined managerial and enforcement strategies to exploit numerous political opportunities. On the managerial side, CICIG commissioner Velasquez and his main public sector ally, Attorney General Aldana, offered three additional press conferences on July 2, August 21, and September 14. Those conferences displayed their agencies’ increasingly sophisticated collaboration, investigation, and informational mechanisms. They also educated the public on the anticorruption norm, unveiling new phases of The Line case and revealing a growing list of suspects, which eventually included the president. In addition, Velasquez, Aldana, and their staffs conducted numerous media interviews, published spots and press releases, and consistently met with civil society and international community supporters to keep them apprised of their findings.

The TAN’s parallel enforcement strategy turned to more coercive tactics. In support of the legal prosecutions, Guatemalans responded to the press conferences by marching weekly, demanding that the president step down. International state and nonstate allies, eventually including even the US ambassador, echoed those pleas in private meetings and public announcements. The growing pressure, alongside the explosive evidence marshaled by the TAN, forced the resignation of seven government ministers in a single day and the arrest of the vice president. After a period of heightened tension, Congress’s unanimous vote to remove his immunity led to Pérez Molina’s ouster and arrest.

If the TAN’s strategies and tactics during that six-month period were coherent and decisive, the Pérez Molina government’s responses, by contrast, proved shifting and contradictory. For instance, in April 2015, the administration abruptly announced its decision not to extend the CICIG’s mandate, which was set to expire later that year. But vocal opposition, including by some of Pérez Molina’s allies in the business sector, prompted the administration to walk back its decision. Seeking to appease an outraged public, the government created a commission to assess the matter. The commission, which included Attorney General Aldana, predictably supported a mandate extension.

The administration’s wavering did not end there. Concerned with the growing discontent, Pérez Molina engaged in a number of symbolic gestures. He met with Commissioner Velasquez, penned a cordial response to the yearly AGO report, organized a press conference for his vice president to offer her perspective on the Line case, and publicly commended the multitudinous anticorruption marches. Yet simultaneously, Pérez Molina’s administration pursued initiatives hostile to the TAN and its supporters. Members of his administration secretly recorded the marches, launched legal appeals to slow down the investigation, minimized and ridiculed protester concerns and influence, and criticized foreign funders.

The erratic, incoherent approach extended to the administration’s efforts to build a support coalition. In some instances, the government dutifully extolled its natural allies, such as the military and certain public sector unions (e.g., the teachers’ union), but failed to extract public statements of support from them. In other cases, its inconsistent positions in regard to the TAN undermined initial affinities, as in its relations with the US Embassy or the traditionally supportive private sector umbrella association CACIF. In still other instances, the Pérez Molina administration proved almost inexplicably coy, as in its refusal to forge a partnership with the political party LIDER, a major force in Congress. Not only would it vote on any congressional initiative to remove Pérez Molina’s immunity, but as a result of the TAN’s prosecution of its leaders in a separate corruption case, LIDER was also independently responding to a legal-political challenge of its own.Footnote 10

From the perspective of the emerging literature on state responses to TAN campaigns (Christensen and Weinstein Reference Christensen and Weinstein2013; Dupuy et al. Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2015, Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2016; Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez 2018), the Pérez Molina administration’s haphazard and failed rejoinder is surprising. Pérez Molina represented the archetypical leader of the “populist playbook”—a strongman with a documented history of participation in repressive activities against civil society actors. Former military officials well versed in counterinsurgency tactics constituted his key advisers. Moreover, he enjoyed high support among the population, controlled a majority of the congressional seats, maintained some independence from US foreign policy, and faced a TAN that challenged his political survival—all conditions predictive of a robust response.

That during the six-month span between April and September 2015, the Pérez Molina administration proved unable to muster a coherent and effective response is largely explained by the poor fit between the administration’s Iron Fist domestic security paradigm and the demands of the TAN legal-political challenge. The paradigm concentrated decisionmaking in the Interior and Defense Ministries. However, the leadership of these ministries was unable to contain a managerial TAN strategy that relied on allied public sector agencies, such as the AGO, that were largely autonomous and therefore beyond their direct control. The Iron Fist paradigm also privileged secrecy in its actions and largely dismissed accountability demands. That feature left it bereft of mechanisms to convincingly counter the TAN’s groundbreaking and compelling informational politics designed to raise the population’s awareness.

Similarly, the Iron Fist paradigm focused militarized security forces on rigid punitive measures and targeted low-income individuals caricatured as violent gang members or drug traffickers. However, it provided few readymade options to undercut the TAN enforcement strategy of massive, cross-class, peaceful marches supported by respected political and civil society actors. It lacked a coherent rejoinder to the high-profile prosecutions against top government officials. It also did little to prevent calls from powerful foreign state and nonstate actors demanding changes in the Guatemalan state’s behavior and openly shaming the “corrupt” government.

Most generally, the Iron Fist paradigm failed to conceive of the TAN challenge as a preponderant domestic security anomaly. As a result, the administration’s responses reflected the ad hoc and experimental nature that the literature on policy learning would predict. They stretched the paradigm’s intellectual coherence. And they not only failed to suppress the TAN challenge, but in enraging the public and undermining possible alliances, probably catalyzed the government’s collapse.

At the same time, the Line investigation and the subsequent erratic government response strengthened the political standing of the TAN. Before that investigation, the TAN faced an uncertain future, as many, including Pérez Molina, favored rescinding the CICIG’s mandate. That opposition evaporated seemingly overnight with The Line’s first press conference. The CICIG and AGO’s public approval ratings soared, and most of Guatemala’s influential political actors expressed their support. Riding the changing political tide, the TAN accelerated its anticorruption norm socialization campaign. Just two years later, that campaign would target the government of Pérez Molina’s successor, President Morales.

2017: The Anticorruption TAN’s Legal-Political Challenge to the Morales Administration

The anticorruption TAN launched its Illicit Campaign Financing—FCN challenge on August 24, 2017. In a press conference, Commissioner Velasquez and Attorney General Aldana implicated President Morales and several others in a corrupt electoral financing scheme. Over the next 18 months, their managerial strategy involved six more press conferences; multiple interviews, spots, and press releases; and meetings with diverse civil society actors. In these public education activities, they drew on a rich base of evidence collected in close collaboration with allied public agencies. They also implemented a parallel enforcement strategy that reignited legal challenges, widespread social mobilization, and a boomerang pattern akin to 2015.

Indeed, the TAN’s 2017 managerial and enforcement strategies essentially followed the blueprint developed through the 2015 Line challenge, notwithstanding the growing predictability of those tactics. The TAN’s past success partly explains this strategic inertia. Yet Guatemalan civil society interviewees, echoing the literature’s common critique of a disconnect between TANs’ professionalized leadership and grassroots organizations (Norman Reference Norman2017; Bownas Reference Bownas2017), also noted the commissioner’s and attorney general’s “stubborn” refusal to heed their supporters’ advice and change their practices.Footnote 11 That rigidity allowed adversaries to decode, foresee, and defang the TAN’s actions.

Shifts in the international political opportunity structure further threatened the TAN campaign’s formidable standing. Most crucially, the US presidential transition from the Obama to the Trump administration would, over time, weaken the boomerang pattern. Together with the TAN’s strategic inertia, this readjustment increased the campaign’s vulnerability to opponent attacks.

The Guatemalan state, under the Morales administration, exploited that vulnerability to engineer an anti-TAN response that precipitated the 2017 challenge’s surprising failure and the transnational campaign’s collapse. Following the first press conference in April, the Morales administration faced the TAN not with Pérez Molina’s hedging ambivalence but with a systematic approach shaped by a new Guatemala First domestic security paradigm. That new paradigm arose from a process of policy learning in the turbulent environment of the anticorruption TAN campaign (see table 1), which had continued unabated after Pérez Molina’s arrest. By 2017, the campaign had led to the corruption-related prosecution of at least four hundred individuals, as well as large-scale mobilization, thereby drawing widespread attention.Footnote 12

However, the relevance of corruption and mobilization as domestic security imperatives largely derived from the interpretation of these campaign-related events as anomalies, according to two competing narrations of crisis. Both narrations dismissed Pérez Molina’s Iron Fist paradigm as ill-suited for the demands of the time. Both viewed the TAN campaign as highlighting crucial security concerns. But the two also radically diverged in their crisis construction modes, diagnoses, and solutions. The TAN embraced the first narration, which pointed to corrupt public-private networks using the state to advance their own private legal and illegal interests as the central domestic security problem affecting Guatemala (CICIG 2017). The alternative narration of crisis, supported by many of the same conservative business and government actors that earlier had favored Pérez Molina’s Iron Fist approach, instead turned attention to the TAN, portraying it as the central security threat. They vocally and influentially portrayed the anticorruption campaign as a fraudulent, “leftist,” foreign-funded ploy to illegitimately manipulate the justice system and influence Guatemalan politics. This narration spawned the Guatemala First paradigm, which rose to prominence in 2017.

Notably, the ascendance of this latter paradigm was far from certain even a year earlier. In fact, following the Pérez Molina legal-political challenge, Morales won the presidential election in late 2015 under an anticorruption banner framed by the slogan “Neither Corrupt Nor a Thief” (Ni Corrupto, Ni Ladrón). However, once in power, Morales and his associates espoused the Guatemala First paradigm. Observers largely agree on the reasons for this remarkable volte-face: in 2016, as the TAN expanded its campaign, it targeted powerful political, business, and military actors, many of whom supported Morales. It even prosecuted members of Morales’s family. It was this latter action which, in the midst of the contest between the two narrations of crisis, finally persuaded President Morales and his allies to support the Guatemala First domestic security paradigm, with its specific problem definition, objectives, and policy instruments.Footnote 13

That decision proved momentous for both the Morales administration and the anticorruption TAN. The new Guatemala First paradigm conceived of the TAN as a domestic security threat bent on sowing disorder, undermining the authority of the state, and illegitimately intervening in Guatemalan politics to remove President Morales.Footnote 14 The new paradigm also shifted the locus of authority. Morales empowered new actors within the state, redirecting decisionmaking authority away from the security ministries and toward a small clique of military advisers (Zamora Reference Zamora2016; Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez2018). He eventually broadened his trusted circle to include the Interior and, of particular note, Foreign Affairs Ministries.

These newly empowered actors deployed the Guatemala First paradigm’s policy instruments, tailored to methodically undermine the TAN’s unchanged managerial and enforcement strategies. To address the TAN’s managerial strategy, the state under Morales removed TAN-aligned public agency leaders. For instance, the administration and its allies in Congress and the courts launched several corruption investigations into Attorney General Aldana’s administration, tarnishing her reputation and eventually driving her into exile. Once her term as attorney general expired in May 2018, Morales’s allies ensured a suitable replacement, selected personally by the president. That leadership change at the AGO mirrored a multitude of other comparable substitutions of government loyalists for TAN allies in agencies such as the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and the Interior, the Tax Collection Agency, and the Comptroller’s Office. The adjustments effectively dissolved TAN—public agency collaboration. Yet they also sacrificed competent leadership and capacity-building initiatives that were already under way. For instance, the incoming interior minister abandoned a police professionalization program; the new tax collection agency director withdrew enhanced revenue plans; and the replacement foreign affairs minister turned her back on Guatemala’s commitment to multilateralism.

In parallel, the Morales administration undermined the TAN’s managerial tactic of information dissemination and civil society education. It constructed a broad anti-TAN coalition that reached well beyond the executive agencies to include congressional representatives, mayors, judges, lawyers, prominent business and religious leaders, television and radio stations, and top figures in the largest public sector unions. Often targeted during the TAN’s relentless anticorruption campaign, these powerful political actors were eager to join the Morales administration’s anti-TAN coalition. In contrast to Pérez Molina’s ambivalent approach to anti-TAN coalition building, the Morales administration proactively and effectively brought them together. These actors then countered the TAN’s media campaign by blanketing newspapers, radio and television shows, and online forums with Guatemala First arguments. They effectively sowed confusion about the anticorruption campaign’s objectives and achievements among the public.

While they subverted the TAN’s managerial strategy, the Morales administration and its anti-TAN coalition also undercut its enforcement tactics. Domestically, the government and its allies assembled the congressional bloc that, drawing representatives from almost every major political party, voted to protect Morales from prosecution. They similarly displayed a nuanced understanding of the latent rifts within the TAN’s multiclass support coalition, activating explosive political and social debates on abortion, gender, same-sex marriage, and even the Cold War specter of a socialist takeover. In underscoring those polarizing issues, the administration and its growing coalition diluted the unity of the anticorruption side.

As they weakened the TAN’s domestic support, the Morales-controlled state and its allies generated competing large-scale assemblages. Most prominent among them was the pro-life march of September 2018, which amassed more than 150,000 people. That mobilization, which arose in response to an abortion-related legal reform proposed by some of the TAN’s supporters in Congress, reinforced the Morales administration’s domestic security objectives. Indeed, Morales explicitly linked the march to his administration’s ongoing efforts by noting that “Guatemala and our government believe in life, in the family based on a man and a woman.

Guatemala and our government [also] want to elect freely, without [foreign] intervention. Guatemala wants freedom!” (Bin Reference Bin2018).

That concern with foreign intervention informed the Morales administration’s actions to blunt the TAN’s boomerang pattern. Recognizing the changing US foreign policy priorities following the 2017 presidential transition, Morales and his allies targeted conservative members of the US government. First, to gain the Trump White House’s support, the Guatemalan government controversially transferred its embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem in May 2018. Guatemala thus became the first country to follow the United States in that contentious diplomatic shift. The decision ingratiated Morales with the Trump administration, earning him a Washington meeting with the US president. It also “allowed [him] to start negotiating directly with the US government, and to eventually receive its tacit blessing in its crusade to undermine [the TAN].”Footnote 15

While that decision targeted the White House, Guatemalan government officials, with support from prominent business leaders, drew on a sovereignty discourse critical of development projects like the CICIG, led by organizations such as the United Nations, to lobby Republican senators wary of multilateralism. They further incited the senators’ suspicions by spuriously suggesting Russian intervention in CICIG activities—specifically, by pointing to the infamous Bitkov case.Footnote 16 Their lobbying persuaded some senators, including Marco Rubio, who, as chairman of the Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere, Transnational Crime, Civilian Security, Democracy, Human Rights, and Global Women’s Issues and a member of the Appropriations Committee, placed a temporary hold on US funding for CICIG.

Sensing the softening US government support for the TAN and the United Nations, Morales’s foreign affairs ministry embarked on a crusade against Commissioner Velasquez. While initially limited to repeated pleas to the UN secretary-general for a replacement, the crusade intensified when authorities temporarily denied Velásquez an extension of his Guatemalan work visa.Footnote 17 It escalated further when the Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared Velasquez non grata and came to an unceremonious end when immigration officials refused him reentry following a trip to New York in September 2018.

With Commissioner Velasquez and Attorney General Aldana forced into exile, the political winds definitively turned on the TAN. By early 2019, it had all but ceased its managerial and enforcement activities. The anticorruption campaign officially concluded in September 2019, when the Morales administration rescinded the CICIG’s mandate. Certainly, the advocacy network’s inertial strategy and the changing US foreign policy created conditions for Morales’s failed prosecution and the TAN’s eventual collapse. However, the bulk of the explanation for this unexpected outcome lies in the systematic response by a state that assessed the results of past policies and adjusted its understanding and approach accordingly by adopting the Guatemala First domestic security paradigm.

Discussion and Conclusions: Implications for TAN Research

Scholars increasingly recognize that even weak targeted states may effectively quash TAN norm socialization campaigns. Abandoning the optimism of older TAN arguments, this recent research examines both the conditions under which vulnerable states are most likely to take anti-TAN steps (Christensen and Weinstein Reference Christensen and Weinstein2013; Zwingel Reference Zwingel2012; Dupuy et al. Reference Dupuy, Ron and Prakash2015 and 2016) and the “populist playbook” available to them (Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez Reference Rodríguez-Garavito and Gómez2018). At the same time, this emerging work largely lacks a contextualized account of the process through which these states devise their particular responses. This article has drawn on the policy-learning literature to explain how shifting domestic security policy paradigms inform those anti-TAN approaches. It has illustrated the argument through a comparison of the divergent impact of the Guatemalan state’s contrasting responses to two similar legal-political challenges, undertaken in the context of the same anticorruption TAN campaign.

This empirical material points to four additional implications. First, following Matejova et al. (Reference Matejova, Parker and Dauvergne2018), it suggests that TAN norm socialization campaigns may inadvertently undermine local civil society actors. By eliciting public sector antipathy, those campaigns may close opportunities for state—civil society collaboration and even threaten vulnerable local TAN partners’ survival. In Guatemala, interviewees expressed their growing fear of a “scorched earth” backlash against the CICIG’s allies.

Second, anticorruption campaigns may also paradoxically weaken targeted states’ capacity. That is because they may induce targeted states to adopt domestic security paradigms that, while focusing on the TAN challenge, often inform policies that sacrifice other state priorities. The replacement of Morales loyalists for competent officials in key state posts, such as the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and the Interior or the Office of Tax Collection, provides the clearest example of this unexpected pitfall.

Third, the empirical material suggests that even weak, peripheral states may decisively affect the extent to which powerful international TAN backers exert pressure through the boomerang pattern. The implication echoes Hirschman’s 1978 “disparity of attention,” which reveals how a small, dependent state may reduce its domination by a rich state by exploiting the gap in the importance each gives to their relationship. Specifically, while the small state will single-mindedly focus on subverting that domination, the rich state will probably pay greater attention to other, more vital interests. The Guatemalan state under the Morales administration illustrates a similar dynamic. Although, even if unprompted, a more isolationist Trump administration would have probably reduced the level of US involvement in Guatemala’s anticorruption campaign, it was the resolute lobbying by the Morales administration and its allies that persuaded US politicians and diplomats not only to step aside but, particularly after early 2018, tacitly to approve the Guatemalan government’s anti-TAN campaign.

Last, while this article underscores the state’s response to norm socializing campaigns, it also calls into question the literature’s established assumption of TAN flexibility, creativity, and adaptability—even for professionalized (Norman Reference Norman2017;

Andonova Reference Andonova2014), broad-based (Bownas Reference Bownas2017), and resource-rich TANs (Hale Reference Hale2020). Certainly, in its 2015 Line challenge, the Guatemalan anticorruption TAN devised novel managerial and enforcement strategies targeting previously untouchable actors. Yet it displayed an equal measure of strategic inertia in 2017. Reliance on a campaign blueprint, while expeditious, may be counterproductive when involving targeted bureaucracies capable of engaging in policy learning. As the Guatemalan example suggests, it may allow these targets to adopt policy paradigms that decode, predict, and defang the blueprint’s strategies and tactics.