INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac dysrhythmia treated in the emergency department (ED).Reference Stiell and Macle 1 In Canada, symptomatic episodes of paroxysmal AF are increasingly managed entirely in the ED, without subsequent admission to hospital.Reference Stiell and Macle 1 - Reference Camm, Kirchhof and Lip 3 ED management of symptomatic AF is focused on ventricular rate control or restoration of sinus rhythm, followed by primary or secondary prevention of thromboembolism.Reference Stiell and Macle 1 Management is guided by multiple considerations, including patient stability, age, comorbidities, and specific characteristics of the patient’s presentation such as AF duration and associated complications (e.g., cardiac ischemia, heart failure, transient ischemic attack/stroke). In low risk patients, restoration of sinus rhythm via electrical or pharmacologic cardioversion is recommended for symptomatic AF of duration less than 48 hours, although no approach has been conclusively proven superior, and wide variations exist among practice sites.Reference Verma, Cairns and Mitchell 2 , Reference Stiell, Clement and Brison 5

Electrical cardioversion is a short, painful procedure that is usually performed under procedural sedation. Multiple medications have been shown to be safe and effective for sedation in the ED, with propofol, ketamine, midazolam, fentanyl, and etomidate being commonly used alone or in combination.Reference Innes, Murphy and Nijssen–Jordan 6 , Reference Campbell, Magee and Kovacs 7 Many studies have evaluated medication combinations for extended procedures, such as fracture reductions or abscess drainage, but few have included electrical cardioversion. Studies evaluating sedation regimens for cardioversion are small and heterogeneous in terms of the sedative agents evaluated.Reference Kalogridaki, Souvatzis and Mavrakis 8 - Reference Coll-Vinent, Sala and Fernández 12 Thus, there is a paucity of evidence to guide sedative medication choice to ensure optimal patient outcomes for electrical cardioversion in symptomatic AF.

The objectives of this study were to first quantify ED practice variation in the selection of sedation medication for electrical cardioversion of AF and atrial flutter (AFL) in eight major academic hospitals across Canada, and secondarily to investigate the adverse event risk associated with different sedative medication choices for a direct current cardioversion.

METHODS

Study design and setting

This is a secondary analysis of two cohort studies describing the ED management of recent onset AF or AFL. Recent Onset Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter-0 (RAFF-0) was a retrospective health records review of ED patients with AF or AFL,Reference Stiell, Clement and Brison 5 whereas Recent Onset Atrial Fibrillation or Flutter-1 (RAFF-1) was a prospective cohort study.Reference Stiell, Borgundvaag and Clement 13

Patients were enrolled in RAFF-0 or RAFF-1 if they were 18 years of age or older with a primary diagnosis of a recent-onset episode (first or recurrent) of symptomatic rapid AF or AFL. Inclusion criteria for both studies included a clear history of onset within 48 hours or onset within 7 days on anticoagulants with an international normalized ratio >2. Patients were excluded if AF or AFL was permanent or if the AF diagnosis was secondary to another primary presentation (e.g., alcohol withdrawal). The research ethics boards at all participating hospitals approved this study.

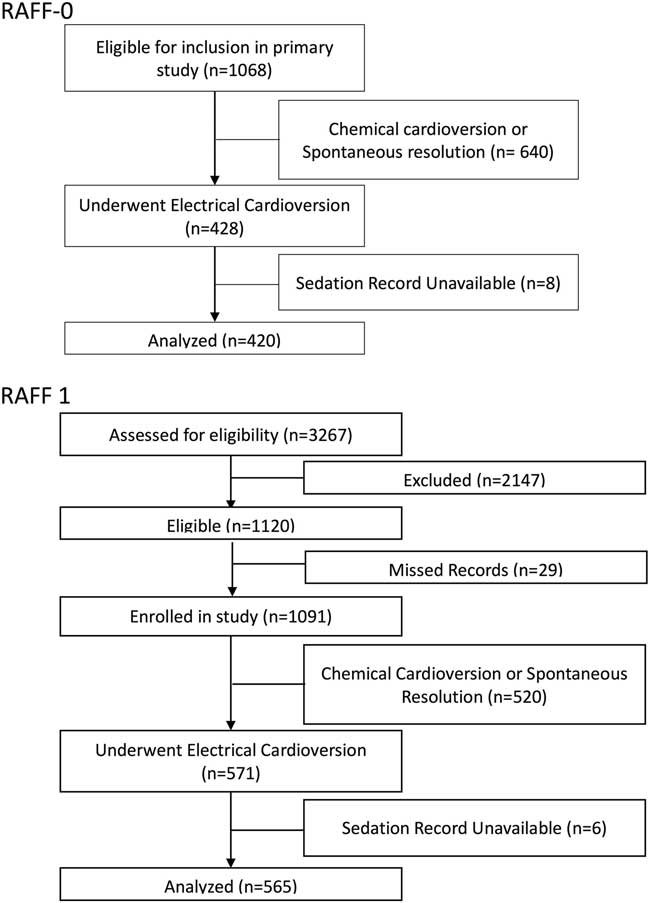

The methods of the RAFF-0 health records review study are described in detail elsewhere.Reference Atzema, Austin and Miller 4 At each site, a trained health records analyst created a list of encounters using electronic hospital database searches. Potential cases were reviewed by a trained research assistant who determined eligibility and abstracted data on a standardized data extraction form. A central experienced research coordinator reviewed cases for completeness and quality assurance. Data were then entered by a trained data entry specialist. This study included 1,068 patients (Figure 1) presenting to eight Canadian academic centres with a primary diagnosis of recent-onset (first episode or recurrent) of AF or AFL from January 1, 2008 to December 31, 2008. Of these, 428 (40%) patients underwent electrical cardioversion, and 420 (98%) had sedation records available and were included in this analysis.

Figure 1 Patient flow diagrams for 1068 patients in RAFF-0 and 3267 patients in RAFF-1.

RAFF-1 was a prospective cohort study at six academic hospitals (all of which had participated in the RAFF-0 study) from January 1, 2010 to January 31, 2012.Reference Stiell, Borgundvaag and Clement 13 All patients had a primary diagnosis of symptomatic rapid AF where symptoms required urgent management and where acute rhythm control was a reasonable option. RAFF-1 subjects were prospectively enrolled when a primary diagnosis of AF (first episode or recurrent) was made by the attending physician. A trained research assistant prospectively recorded ED management as well as abstracted outcome data from patient records. Of the 3,267 patients screened for the RAFF-1 study, 1,120 met study inclusion criteria, and of those 1,091 patients were enrolled. Of the enrolled patients, 571 (52%) patients underwent electrical cardioversion, and 565 (99%) had sedation records available to be included in this analysis (see Figure 1).

Participating hospitals are academic tertiary care centres in Canada and have an annual ED census between 45,000 and 80,000 patients.

Data analysis

Baseline subject characteristics as well as within- and among-site variation in sedation medication choices were quantified with descriptive statistics. Where possible, temporal variations within and between sites were examined by comparing the RAFF-1 and RAFF-0 data sets. Due to heterogeneity in study design, outcome definition, and ascertainment, data sets were analysed individually and not pooled.

Sedative regimens examined included propofol alone, propofol/fentanyl, propofol/midazolam, propofol/fentanyl/midazolam, and propofol/other. The propofol/other drug combination comprised propofol/ketamine, propofol/other (specific other drug not recorded), or propofol/fentanyl/other, each of which was used with very small frequency.

Adverse events were abstracted from medical records and included negative sequelae due to sedation. The RAFF-0 study classified adverse events into aspiration, hypoxia (saturation <90%), or “other.” Trained nurses using charts and reviewing sedation records classified “other” adverse events to include bradycardia, emesis, apnea, manual airway control, as well as “not defined.” The RAFF-1 study defined adverse events as either hypoxia or aspiration.

Unadjusted relative risks for adverse event occurrence were calculated for the four sedative combinations compared to propofol alone. To adjust for potential confounders, we conducted a main-effects multinomial logistic regression analysis with the incidence of adverse events as the outcome. Regression models were constructed using clinically and conceptually relevant covariates and used a backward stepwise variable selection procedure. The final model was included as potential confounders: systolic blood pressure <120 mm Hg, use of IV rate control medications prior to sedation, age >65, and patient use of oral antihypertensive agents.

For each data set, regression models were fitted to generate an adjusted odds ratio for each drug combination compared to propofol alone. Due to the low number of adverse events in the RAFF-1 data set, bivariable and regression analyses were not able to be performed for the drug combinations of propofol/fentanyl/midazolam and propofol/midazolam.

Data analysis was conducted with SPSS statistical software, version 17.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

Patient enrolment for RAFF-0 and RAFF-1 is shown in Figure 1. Patient demographics are presented in Table 1. Patients were predominantly male, 66.4% and 68.8% (RAFF-0 and RAFF-1), age 59 (RAFF-0) and 60.4 years old (RAFF-1). Presenting rhythm was AF in 87.6% of RAFF-0 patients and 82.3% of RAFF-1 patients. Initial duration of symptoms was 11.4 hours and 7.6 hours in RAFF-0 and RAFF-1, respectively. Cardioversion success rates by medication choice are shown in Table A1 (see supplementary material).

Table 1 Patient demographics in RAFF-0 and RAFF-1 data sets

CAD = coronary artery disease; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR = heart rate; SD = standard deviation.

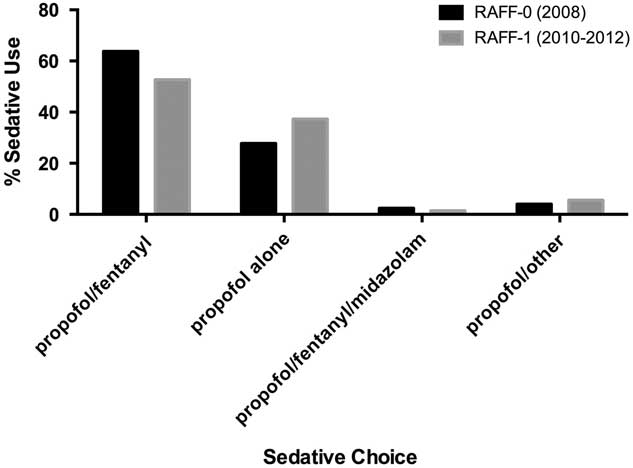

In both data sets, the combination of propofol/fentanyl was the most commonly used sedative regimen (63.8% and 52.7% for RAFF-0 and RAFF-1, respectively), followed by propofol alone (27.9% and 37.3% for RAFF-0 and RAFF-1, respectively) (Figure 2, Table 2).

Figure 2 Bar chart showing sedative choice in RAFF-0 and RAFF-1.

Table 2 Drug combination use in each data set with the corresponding adverse event percentage

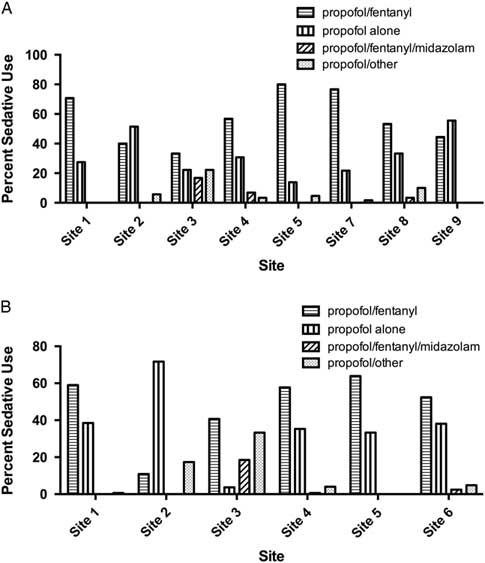

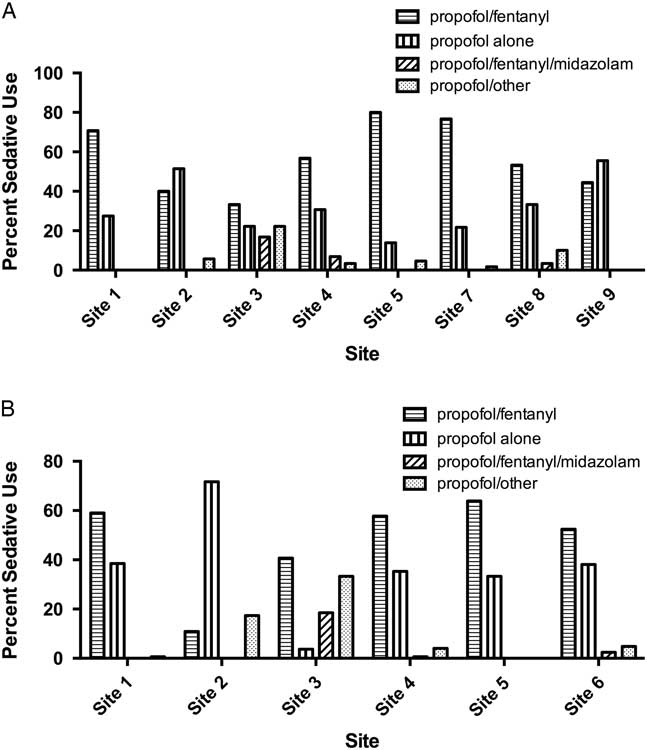

There was substantial variation in sedative choice among EDs. In the 2008 cohort, six of eight sites primarily used propofol in combination with fentanyl, whereas two sites primarily used propofol alone (Figure 3, A). From 2010 to 2012, propofol/fentanyl was used most frequently at five of six hospitals (Figure 3, B).

Figure 3 Bar chart showing sedative choices in A) eight academic tertiary care centers in RAFF-0 and B) six centers in RAFF-1.

At sites with data from each temporally separate cohort (Sites 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5), the use of propofol alone increased from 27.7% in 2008 to 37.4% in 2010 – 2012, whereas the use of the propofol/fentanyl in combination decreased from 62.4% to 50.5%.

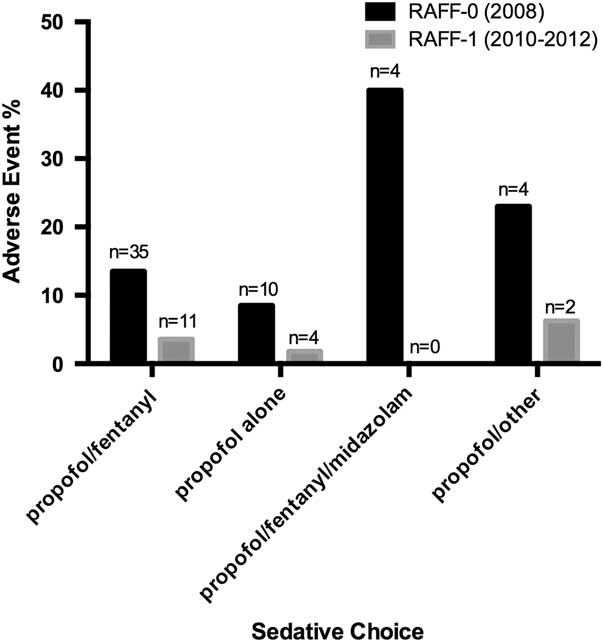

The RAFF-0 data set contained 58 cardioversions with sedation-related adverse events (13.5%), of which 57 had sedative records available, whereas the RAFF-1 data set contained 19 adverse events (3.3%). Figure 4 shows the pooled adverse events by sedative type, and Tables A2 and A3 (see supplementary material) show adverse event by sedative type. The majority of adverse events were associated with the combination of propofol/fentanyl/midazolam (22%). Table A4 shows the unadjusted relative risks of an adverse event for each medication compared to propofol alone in each data set.

Figure 4 Bar chart showing sedative choice and adverse event risk in RAFF-0 and RAFF-1.

Multinomial logistic regressions evaluated the comparative risk of adverse events for the sedative regimens compared to propofol alone, after adjusting for potential confounders. In the RAFF-0 data set, the use of propofol/fentanyl/midazolam in combination was associated with a higher risk of and adverse events compared to propofol alone. No sedative combination was associated with an increased adjusted risk of adverse events compared to propofol alone in the RAFF-1 data set (Table 3).

Table 3 Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for adverse events associated with sedative medication combinations compared to propofol alone, after adjustment for confounders

CI=confidence interval; OR=odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

This study examines the variation in sedation medication choices for electrical cardioversion in two geographically distributed patient cohorts with acute, symptomatic AF. The most commonly used sedative was a combination of propofol/fentanyl, followed by propofol alone. However, substantial variation was observed in sedation medication choices among the different sites, particularly in the use of agents combined with propofol. Although evidence supports the use of propofol and ketamine mixtures for procedural sedation,Reference Andolfatto, Abu-Laban and Zed 14 - Reference Messenger, Murray and Dungey 16 only two sites used this combination to any appreciable extent. This variation is not surprising given the other variation in RAFF-1 management previously observed between these same hospitals.Reference Atzema, Austin and Miller 4 Comparing the RAFF-0 and RAFF-1 data sets temporally, the use of propofol/fentanyl declined roughly 10%, with the majority of this decline attributable to increased use of propofol alone as a sedative agent.

Choosing the medications required for any sedation requires physicians to balance effectiveness against potential adverse effects. Guidelines support the safety of multiple agents, including propofol and ketamine, for procedural sedation.Reference Godwin, Burton and Gerardo 17 To date, only small studies evaluating the safety and effectiveness of these agents specifically in electrical cardioversion have been conducted.Reference Kalogridaki, Souvatzis and Mavrakis 8 - Reference Coll-Vinent, Sala and Fernández 12 No studies have directly compared propofol and fentanyl or propofol and ketamine against propofol alone for electrical cardioversion.

Propofol and fentanyl both can cause apnea at high doses and can have an additive effect when used together. Practitioners may believe that the risk of an adverse event with the addition of fentanyl to propofol is not worth the potential benefit of increased analgesia, which may explain the increased use of propofol alone as a sedating medication from 2008 to 2012.

A secondary aim of this analysis was to examine the risk of adverse effects of sedation medication choices for cardioversion. The addition of fentanyl and midazolam to propofol was found to significantly increase the risk of an adverse event in the RAFF-0 data set compared to propofol alone. The drug combination of propofol/other was also found to significantly increase the risk of an adverse event compared to propofol alone in the RAFF-0 data set. In both data sets, the use of propofol/fentanyl was not associated with an increased adverse event risk compared to propofol alone, after adjusting for potential confounders. This suggests that the analgesic benefit of adding fentanyl to propofol may be worth the risk of excessive patient sedation.

LIMITATIONS

A recent review of propofol use in the ED for all procedural sedations showed propofol alone to cause a hypotensive event between 0% and 17% of the time.Reference Black, Campbell and Zed 18 The adverse event risk in these data sets matches these cited event rates. However, there was a surprising difference in the risk of adverse events between the two data sets analysed here. This is likely due to differences in the definition of adverse events in each cohort study and the method of collection. The adverse events collected in RAFF-1 were collected by nurses prospectively and only included aspiration and hypoxia with no other options. The definition of adverse event in RAFF-0, collected retrospectively from all sections of the patient’s chart (sedation record, respiratory therapist notes, physician notes), was much broader, leading to a higher adverse event risk in this data set. Aspiration and hypoxia event rates were similar between data sets. Some clinically important adverse events, such as respiratory depression,Reference Bhatt, Kennedy and Osmond 19 were omitted from both data sets, thus leading to a possible underestimate of the adverse event risk.

Another important limitation stems from the individualized nature of medication choice. Physicians were able to tailor medication choice and dose to the individual patient. Thus, the observed results may be vulnerable to selection and indication bias. However, no significant demographic differences were observed between those who suffered an adverse event compared to those who did not.

CONCLUSION

The risk of adverse events from procedural sedation for cardioversion in the ED is low but not negligible, and retrospective analysis in the RAFF-0 data set failed to demonstrate increased risk of adverse events with the combination of propofol/fentanyl compared to propofol alone. These data demonstrate substantial differences in medication choice within and among Canadian academic centres. Over time, it appears that multimodal sedation is becoming less popular compared to using propofol alone for cardioversion.

Acknowledgements: Dr. Stiell holds a Distinguished Professorship and University Health Research Chair from the University of Ottawa. Dr. Rowe is supported by a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Evidence-based Emergency Medicine through the Government of Canada (Ottawa, ON). Dr. Perry holds a New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a Clinical Research Chair from the University of Ottawa. We would like to thank the research staff at participating hospitals for their contributions towards patient enrolment and follow-up, as well as data collection. The authors acknowledge the following research personnel at the study hospitals: The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario (Pam Sheehan, RN; Pam Ladoucer, RN; Julie Finnigan, RN; Connor Sheehan, BAH; Ellias Horner, BAH; and Linda Brown, RN); Kingston General Hospital, Kingston, Ontario (Kathy Bowes, RN; Karen Lollar, RN; Jane Reid, RN; Nicholas Martin, MD; Gauri Ghate, MD; Carla Graham, RN; and Catherine Bobek, MD); Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario (Michelle Loftus, RN; Genevieve Banshard, RN; and Jackie Ripco, RN); Jewish General Hospital, Montreal, Quebec (Antoinette Colacone, RN; Chris Tselios, BSc; and Paulina Gasioworska, MD); University of Alberta Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta (Debbie Boyko, RN; Jennifer Moore, RN; Mira Singh, MA; Gemma Percival, RN; and Jennifer Goede, RN); Foothills Medical Centre, Calgary, Alberta (Renee Vilneff, RN; Karen Melon, RN; Allan Kostyniuk, BA; Hachem Nasri, MD; Fareen Zaver, MD; Rebecca Machacek, RN candidate; Stevie Anderson, RN candidate; and Carly More, RN candidate); St. Paul’s Hospital, Vancouver, British Columbia (Mahi Etminan, RN; Iraj Poureslami, PhD; Arash Eftekhari, MD; and Maziar Sighary, BSc); Queen Elizabeth II HSC, Halifax, Nova Scotia (Agnieszka Grabowski-Comeau, RN). The authors also acknowledge staff of the hospital health records departments, our colleagues at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, and the staff responsible for coordinating these studies (Maureen Lowe, My-Linh Tran, Angela Marcantonio, Sheryl Domingo, Connor Sheehan, BA; and Jennifer Brinkhurst, BA) for their assistance with this project, and Dr. Eddy Lang for his insightful suggestions for the article. Finally, we would like to thank the emergency department physicians and nurses at all participating sites for assisting research teams with identifying potential patients and data collection.

Competing interests: None declared.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2017.20