In 2009 we published an article in this journal on hoarding and dilemmas around this condition (Lopez Gaston Reference Lopez Gaston, Kiran-Imran and Hassiem2009). Uncertainties focused on whether hoarding disorder was part of obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and how emerging differences in neuroimaging, neurophysiology, familial and genetic studies, as well as clinical research, could perhaps place the condition independently in its own diagnostic category. Since then, and following the publication of DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013), hoarding disorder has been recognised as a standalone diagnosis. This article will update readers on the implications of this for patients, clinicians and researchers in the area.

Nosology and classification: hoarding as an independent disorder

Prior to DSM-5, the nosological status of hoarding remained largely unresolved owing to selection biases (samples included patients seeking treatment for OCD), inadequate definitions, variability in assessments and reported comorbidities, all of which led to inaccurate results (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a; Marchand Reference Marchand and McEnany2012). DSM-5 improved the diagnostic accuracy of hoarding disorder by establishing a clear set of criteria with the potential to facilitate identification of cases, increase diagnostic reliability and establish the prevalence of the disorder and its comorbid conditions, all of which affect treatment provision and, in return, alleviation of suffering for people with the disorder (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012).

Those defending the departure from the OCD dimension established that, when study participants were recruited using the proposed DSM-5 criteria for hoarding disorder (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a), less than 20% met criteria for OCD. Studies have reported that 75% of patients with hoarding disorder have a concurrent mood or anxiety disorder and severe hoarding symptoms are equally prevalent in individuals with anxiety disorders (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a; Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012, Reference Mataix-Cols2014). Hoarding symptoms are often unnoticed as clinicians do not ask about them (Tolin Reference Tolin, Meunier and Frost2011a). Epidemiological studies also show that a small number of patients with hoarding disorder meet the criteria for OCD (Samuels Reference Samuels, Bienvenu and Grados2008; Brakoulias Reference Black, Monahan and Gable2013) and therefore conclusions drawn from OCD samples might not fully represent individuals with hoarding disorder (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a).

Critics of the new classification highlight studies in OCD samples where OCD symptoms (including hoarding) co-occur at high rates, stating that the isolation of hoarding attempts to increase the understanding of only one aspect of OCD (Brakoulias Reference Brakoulias2013). Concerns are also related to the tendency to create new disorders and the risk of pathologising normal behaviour and overdiagnosing (Allen Reference Allen and Pérez Oliva2014), particularly in cases where boundaries between normality and pathology remain blurred (Reference Black, Monahan and GableBrakoulias 2013; Wakefield Reference Wakefield2013).

Hoarding disorder is a new category in DSM-5 and its criteria (Box 1) are based on Frost & Hartl's (Reference Frost and Hartl1996) original work. Research largely supported the separation of hoarding disorder from OCD on the premise that both disorders might have distinct phenomenological, genetic and pathophysiological bases (Mataix-Cols & Pertusa, Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012; Wakefield Reference Wakefield2013).

BOX 1 DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder

Criteria

• Persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value

• This difficulty is due to both a perceived need to save the items and distress at the thought of discarding them

• The difficulty in discarding possessions results in the accumulation of possessions that congest and clutter active living areas and substantially compromises their intended use; if living areas are uncluttered, it is only because of the interventions of third parties (e.g., family members, cleaners, or authorities)

• The hoarding causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (including maintaining a safe environment for self and others)

• The hoarding is not attributable to another medical condition (e.g., brain injury, cerebrovascular disease, or the Prader-Willi syndrome)

• The hoarding is not better explained by the symptoms of another mental disorder (e.g., obsessive in obsessive-compulsive disorder, decreased energy in major depressive disorder, delusions in schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder, cognitive deficit in major neurocognitive disorder, or restricted interests in autism spectrum disorder)

Specify if:

• With excessive acquisition: if difficulty discarding possessions is accompanied by excessive acquisition of items that are not needed or for which there is no available space.

Specify:

• With good or fair insight: the individual recognizes that hoarding-related beliefs and behaviors (pertaining to difficulty discarding items, clutter, or excessive acquisition) are problematic.

• With poor insight: the individual is mostly convinced that hoarding-related beliefs and behaviors (pertaining to difficulty discarding items, clutter, or excessive acquisition) are not problematic despite evidence to the contrary.

• With absent insight/delusional beliefs: the individual is completely convinced that hoarding-related beliefs and behaviors (pertaining to difficulty discarding items, clutter, or excessive acquisition) are not problematic despite evidence to the contrary.

Pathologising the healthy or identifying the ill?

The ‘adaptive’ tendency to collect or hoard when resources are scarce (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012) has been compounded by the need ‘to possess’ driven by the consumerism of modern society (Cole Reference Cole2010; Marchand Reference Marchand and McEnany2012). When ‘possession’ is taken to extremes it can impair private, social and occupational life and pose serious risks to health and safety (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012; Wakefield Reference Wakefield2013). When hoarding is severe enough to meet diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder, clutter prevents the normal use of space to accomplish basic activities of daily living (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012).

The estimated prevalence of hoarding disorder in community studies (Iervolino Reference Iervolino, Perroud and Fullana2009; Timpano Reference Timpano, Exner and Glaesmer2010) is 2–6% in adults and 2% among adolescents, which is twice the rates for OCD (Ivanov Reference Ivanov, Mataix-Cols and Serlachius2013). Studies suggest that prevalence does not vary with gender and that it increases with age, alongside the chronicity of the disorder if there is no intervention (Iervolino Reference Iervolino, Perroud and Fullana2009; Timpano Reference Timpano, Exner and Glaesmer2010).

Hoarding disorder constitutes a substantial burden for sufferers, family and society at large. Despite media interest and a recent increase in public awareness (in the UK, Channel 4's The Hoarder Next Door ran for three series between 2012 and 2014, and the BBC's Britain's Biggest Hoarders was first shown in 2013), help-seeking remains low and tends to be driven by comorbid conditions (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a; Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012, Reference Mataix-Cols2014). Hoarding disorder also constitutes a public health burden: it is associated with greater rates of chronic medical illnesses, increased psychiatric comorbidity and reduced levels of functioning (Wakefield Reference Wakefield2013). The community impact of hoarding disorder can lead to the violation of local health, housing and sanitation laws, resulting in agencies needing to intervene to protect the individual and those living nearby (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Williams2000).

Hoarding disorder versus collecting

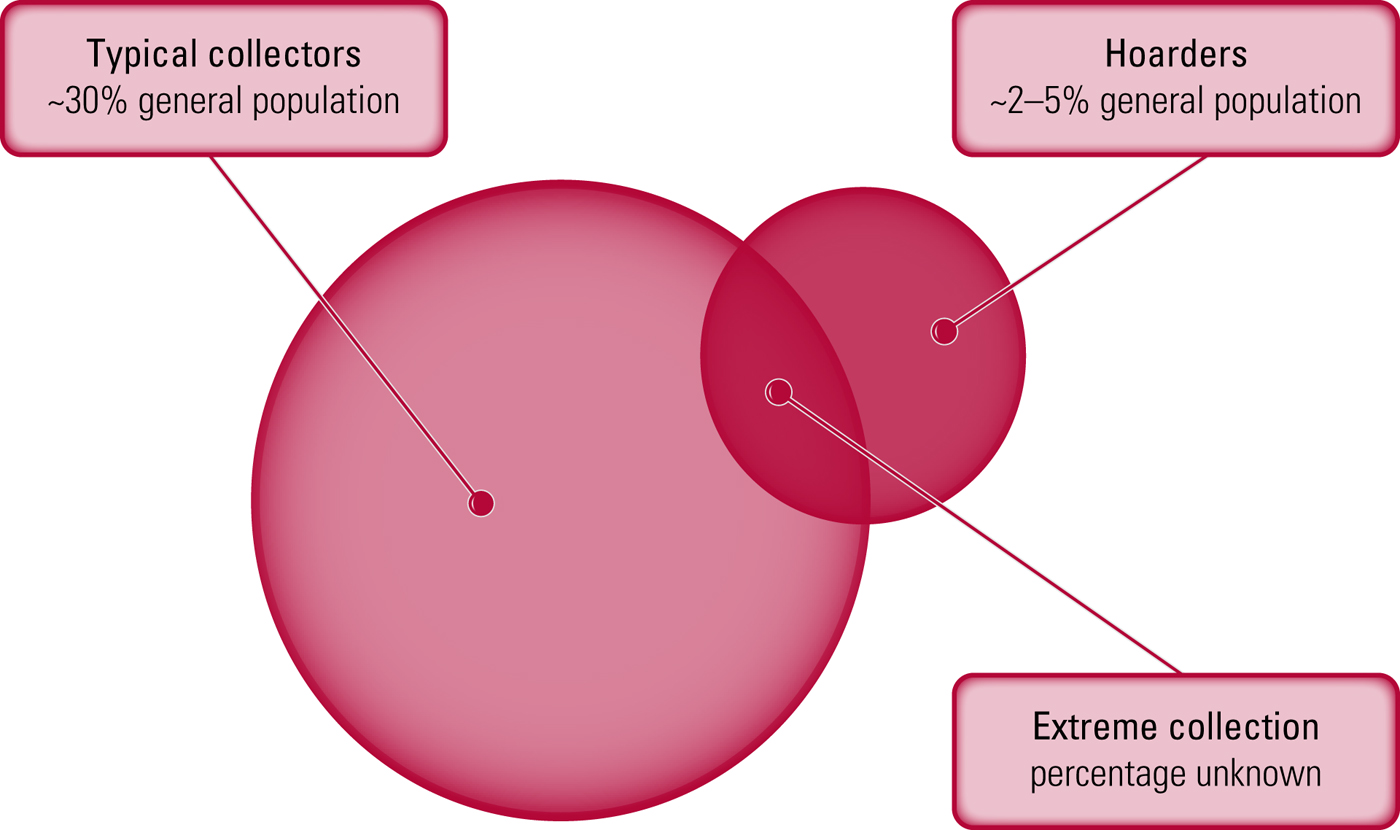

Hoarding disorder needs to be differentiated from widespread and highly prevalent (>30%) normative collecting (Nordsletten Reference Nordsletten and Mataix-Cols2012). A tendency to collect or store objects from an early age (observed in 70% of ‘normal’ children by age 6) has led to the suggestion that hoarding could be an evolutionarily conserved adaptive behaviour to enhance survival and reproductive success (Pertusa Reference Pertusa, Frost and Fullana2010).

Nordsletten & Mataix-Cols (2012) defined collecting as an ego-syntonic leisure activity with psychological benefits that involves methodological acquisition and organisation of a narrow range of items, in which the individual retains good or reasonable insight. Collected items tend to be non-identical, carefully selected and part of a cohesive set and are likely to be traded or sold when no longer fit for purpose (Belk Reference Belk, Frost and Steketee2014). Collectors tend to be male, free from psychiatric conditions and with homes unimpaired by clutter (Belk Reference Belk, Frost and Steketee2014).

On the other hand, hoarding disorder is linked to problematic object accumulation with a tendency to hinder normal performance, impairing individual, interpersonal and occupational functioning (Nordsletten Reference Nordsletten and Mataix-Cols2012). Hoarding disorder is unstructured, non-purposeful and a haphazard extreme consumption activity, socially denigrated as wasteful (Belk Reference Belk, Frost and Steketee2014).

Collectors could potentially fulfil four of the established criteria for hoarding disorder, but the criteria linked to clutter, impairment and distress would set the two behaviours apart (Nordsletten Reference Nordsletten and Mataix-Cols2012). However, full diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder could apply to a small cohort of ‘extreme collectors’ (Nordsletten Reference Nordsletten and Mataix-Cols2012) (Fig. 1).

FIG 1 Hoarding versus collecting: where does pathology diverge from play? Reproduced from Nordsletten & Mataix-Cols (Reference Mataix-Cols and Pertusa2012).

Assessment of hoarding disorder

Home visits and collateral information add objectivity to the patient’s sometimes distorted perception of their hoarding behaviour (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols, Billotti and Fernández de la Cruz2013). Photographs can be useful as an assessment tool and also to track treatment outcomes and help the individual to develop insight throughout therapy (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2008).

Measuring hoarding

Assessment tools specifically developed and validated to measure hoarding disorder symptoms as defined by DSM-5 are outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Instruments for measuring hoarding

In Frost's (Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2012) multidimensional model of hoarding disorder it is posited that individuals do not discard possessions in order to avoid anxiety associated with decision-making and discarding. According to this model, positive emotions facilitate acquiring and saving and there is a perceived usefulness, aesthetic value and/or strong sentimental attachment to possessions (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2012). Also, there is a dynamic interplay between beliefs, emotional attachment and avoidance behaviours aimed at preventing the distress associated with discarding, underpinned by information processing deficits in areas of attention, categorisation, memory and decision-making (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2012).

Thoughts associated with hoarding are not intrusive, unwanted, distressing or repetitive but rather part of a normal stream of thought (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols, Frost and Pertusa2010).

The degree of clutter in the living environment can range from moderate to severe (Pertusa Reference Pertusa, Frost and Fullana2010). Clutter can pose a fire hazard (blocked exits, accumulation of flammable materials), piled clutter increases the risk of injury from falling, and health can be threatened by contamination from rotting foods and exposure to dust pollen and bacteria (poor sanitation) (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Williams2000, Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a). The individual is usually unaware of the severity of the behaviour (Steketee Reference Steketee, Frost and Kyrios2003) and tends to rationalise it and resist intervention.

Hoarding behaviour can occur in the context of neurological and psychiatric conditions such as brain lesions, dementia, developmental and genetic disorders, and schizophrenia (Pertusa Reference Pertusa, Frost and Fullana2010). In most of these conditions the hoarding behaviour appears to be purposeless and better conceptualised as ‘repetitive and dysfunctional’ without specific reasons, motivation or specific value attached to possessions unlike hoarding disorder (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Differential diagnosis between hoarding disorder and hoarding behaviour that is a symptom or manifestation of a neurological condition

Reproduced from Mataix-Cols et al (2011).

What do people hoard?

Marchand & McEnany (Reference Marchand and McEnany2012) and Storch et al (Reference Storch, Bagner and Merlo2007) distinguish between the hoarding patterns of children and adolescents (toys, pencils, rotting food, discarded wrappers) and those of adults (magazines, newspapers or general waste such as dirty napkins and bags).

Animal hoarding is defined as the accumulation of a large number of animals accompanied by neglect (failure to provide minimal standards of nutrition, sanitation and veterinary care). Animal hoarders often lack awareness of the negative consequences of their behaviour. Problems with early attachments, chaotic childhood home environments, as well as attribution of human qualities to animals have been identified as potential factors influencing this behaviour (Patronek Reference Patronek and Weiss2012).

The course of hoarding disorder

Hoarding disorder is often chronic and progressive. Hoarding behaviours tend to start in childhood (Ayers Reference Ayers, Saxena and Golshan2010), everyday functioning is compromised by the mid-20s, with clinically significant impairment by the mid-30s (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols2014). Elderly people become socially isolated (Ayers Reference Ayers, Saxena and Golshan2010), with high risks of self-neglect, poor hygiene and environmental hazards, often due to lack of insight (Koenig Reference Koenig, Chapin and Spano2010). A survey conducted across 88 health officers (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Williams2000) reported that only half of people who hoarded recognised the lack of sanitation in their homes, and less than one-third were willing to cooperate to resolve the problem. The survey also highlighted that animal hoarding was more serious and difficult to deal with.

Comorbidity

The previously mentioned sample recruited using DSM-5 criteria for hoarding disorder (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a) showed that the rate of comorbid OCD (18%) was higher than in the general population (1–2%). Almost 75% of the sample had either a mood or an anxiety disorder, and major depressive disorder was the most prevalent comorbid condition, followed by general anxiety disorder and social phobia.

Another study found that 61% of participants with hoarding disorder had clinically significant compulsive buying; when the tendency to acquire free things was included the rate rose to 86% (Frost Reference Frost, Tolin and Steketee2009). A link between kleptomania and hoarding disorder has been suggested, along with the proposal that hoarding disorder is part of a broader category of ‘psychopathologies of acquisition’ that includes hoarding, buying and kleptomania (Pertusa Reference Pertusa, Frost and Fullana2010).

Inattentive attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has been reported to be significantly more frequent in hoarding disorder than in OCD, and this might be linked to information-processing deficits (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a). Of the personality disorders, obsessive–compulsive personality disorder appears to be most commonly associated with hoarding disorder (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a).

Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder are not significantly higher in hoarding disorder, even though almost 50% of participants reported ‘traumatic experiences at some point in their lives’ (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a; Tolin Reference Tolin2011b). This could be related to the differing definitions of trauma used in various studies. Hoarding might act as means of strengthening the individual's sense of safety after trauma, which is consistent with the perception of possessions as sources of comfort and security (Tolin Reference Tolin2011b).

Familial and environmental factors

A strong familial component in hoarding symptoms might suggest genetic vulnerability: Samuels (Reference Samuels, Bienvenu and Pinto2007a, Reference Samuels, Bienvenu and Pinto2007b) reported that 12% of patients with OCD and comorbid hoarding had a first-degree relative with hoarding and 49% presented some hoarding symptoms, compared with 3% and 33% respectively in OCD patients without hoarding. Indecisiveness is more common in OCD patients with hoarding (59%) and is strongly associated with hoarding in a relative (Samuels Reference Samuels, Bienvenu and Pinto2007a,Reference Samuels, Bienvenu and Pintob). Chromosome 14 has been found to have a suggestive link to hoarding among families with OCD (Samuels Reference Samuels, Shugart and Grados2007b) and OCD patients with hoarding show a high prevalence of the L/L genotype of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism (Lochner Reference Lochner, Kinnear and Hemmings2005).

The only twin study of hoarding disorder (Iervolino Reference Iervolino, Perroud and Fullana2009) found that genetic factors accounted for about 50% of the variance of the disorder, with non-shared environment accounting for the other half. Familial and environmental vulnerabilities, along with traumatic or stressful events, may play a role in the onset, course or expression of hoarding (Tolin Reference Tolin2011b); 55% of hoarding individuals report experiencing a stressful event close to the onset of hoarding (Tolin Reference Tolin2011b) and further research exploring putative environmental risk factors is needed.

Neuropsychological and neurophysiological research

Grisham & Baldwin (Reference Iervolino, Perroud and Fullana2015) identified three main neurocognitive areas linked to hoarding disorder: attention, memory and executive functioning. Attention deficits (‘distractibility’) seemed central to the inability to organise, manage clutter and maintain focus during exposure to organisational tasks; individuals show ‘biased memory beliefs’ and ‘a strong need’ to keep possessions in sight so that they do not forget them (Grisham Reference Grisham and Baldwin2015). Deficits in executive functioning translate into: marked difficulties with impulse inhibition, planning and decision-making; poor self-regulation; difficulties initiating and completing tasks; and problems with indecision. All of these can have a direct impact on the ability to organise or discard possessions (Grisham Reference Grisham and Baldwin2015).

Neuroimaging studies have identified ventromedial prefrontal/cingulate and medial temporal regions in the mediation of non-organic hoarding symptoms (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols, Pertusa and Snowdon2011). A review of brain damage sequalae (Anderson Reference Anderson, Damasio and Damasio2004) that tested 86 people with lesions to the telencephalon related the neuroanatomical placement of the lesion to the presence of repetitive and indiscriminate discard behaviours. High-resolution 3-D scans were used alongside standardised questionnaires to assess hoarding. Thirteen participants exhibited abnormal collecting, characterised by massive and disruptive accumulation of useless objects, and they had no history of any hoarding behaviours before they acquired the lesions.

Saxena et al (Reference Saxena, Brody and Maidment2004) carried out positron emission tomography (PET) scans on 45 people with OCD, 12 of whom had hoarding disorder. Those with hoarding disorder had significantly lower glucose metabolism in the posterior cingulate gyrus and cuneus, whereas those without the disorder had significantly higher glucose metabolism in the bilateral thalamus and caudate. Resting anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) activation in those with hoarding disorder was below that in the non-hoarding participants and in healthy controls. These findings were replicated by Tolin et al (Reference Tolin, Stevens and Villavicencio2012), who compared 43 people with hoarding disorder with 31 individuals with non-hoarding OCD and 33 healthy controls. Functional magnetic resonance imaging was used to examine neural activation across three object-related decision-making areas. During in vivo discarding of novel objects, ACC activation was significantly lower in participants with hoarding disorder than in those with OCD or healthy participants. Activation of the ACC and insula was significantly higher in hoarding disorder during both in vivo and imaginary discarding when decisions about possessions were analysed (Tolin Reference Tolin, Stevens and Villavicencio2012).

Grisham & Baldwin (Reference Grisham and Baldwin2015) also described a pattern of exaggerated neural response in the ACC and precentral and superior frontal gyri and related areas during a key aspect of hoarding disorder: refusal to part with possessions.

Event-related potential (ERP) studies have provided further evidence for the role of the ACC in hoarding disorder through examining error-related negativity (ERN) originating in the ACC. A meta-analysis of the ERP studies comparing ERN amplitudes across individuals with hoarding disorder and individuals with non-hoarding OCD found a trend for an enhanced (high-amplitude) ERN in hoarding disorder that reached significance despite low statistical power and methodological heterogeneity (Mathews Reference Mathews, Perez and Delucchi2012).

Hoarding individuals present with an inability to make decisions due to overwhelming emotions and error vigilance, and the dorsal ACC with connections to medial prefrontal structures is thought to be involved in decision-making, error monitoring and reward-based learning. The central ACC with connections to limbic structures is thought to aid in assigning emotional and motivational salience to stimuli and experiences (Grisham Reference Grisham and Baldwin2015).

Treatment of hoarding: a biopsychosocial approach

Psychological interventions

There is promising evidence suggesting the efficacy of specialised individual and group cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for hoarding disorder (Tolin Reference Tolin, Frost and Steketee2015). In individuals with entrenched problems, realistic goals such as harm reduction might be a clinically valid and more feasible option (Gibson Reference Gibson, Rasmussen and Steketee2010). Identification of concomitant psychiatric disorders is very important, as treating such conditions in their own right can improve overall outcome (Tolin Reference Tolin2011b).

Historically, CBT for hoarding disorder has been associated with poor response and premature drop out. The disorder has often been described as difficult to treat, partly because of patients’ deficient insight into the problem and lack of motivation to change (Steketee Reference Steketee, Frost and Tolin2010; Grisham Reference Grisham and Baldwin2015). However, hoarders have been underrepresented in most CBT studies of OCD, limiting the generalisability of the results (Mataix-Cols Reference Mataix-Cols, Marks, Greist, Kobak and Baer2002).

The pillars of CBT specifically adapted for hoarding disorder (Tolin Reference Tolin2011b; Frost Reference Frost and Steketee2014; Tolin Reference Tolin, Frost and Steketee2015) are:

• motivational interviewing: of prime relevance owing to high levels of limited insight and ambivalence towards change (Tolin Reference Tolin2011b)

• training in sorting and discarding by practising effective decision-making and using challenging questions; home visits provide an invaluable contextual learning experience (Gibson Reference Gibson, Rasmussen and Steketee2010), although practical assistance from removals companies and professional organisers can be considered (Tolin Reference Tolin2011b)

• graded exposure to non-acquiring on outings with the patient to public places (Gibson Reference Gibson, Rasmussen and Steketee2010)

• cognitive restructuring by identifying and correcting maladaptive patterns of thinking (Gibson Reference Gibson, Rasmussen and Steketee2010; Tolin Reference Tolin2011b).

Treatment can incorporate ‘coaches’ (family members, close friends or professional organisers) alongside clinical staff (Gibson Reference Gibson, Rasmussen and Steketee2010).

A meta-analysis conducted by Tolin et al (Reference Tolin, Frost and Steketee2015) examined the effect of CBT on hoarding disorder. Symptom severity decreased significantly across studies, with a large effect size. The strongest effects were seen for difficulty discarding, followed by clutter and acquiring. Female gender, younger age, a greater number of CBT sessions and home visits were associated with better clinical outcomes.

Cognitive–behavioural interventions based on Steketee & Frost's manualised CBT treatment model have had promising results (Steketee Reference Steketee and Frost2007). In a controlled trial, 46 patients with hoarding disorder were randomly assigned to receive either CBT (involving >25 weekly 60-minute individual therapy sessions plus home visits over a period of 9–12 months) or to remain on a waiting list (Steketee Reference Steketee, Frost and Tolin2010). After 12 weeks, 10 of 23 (43%) participants in the CBT group were rated as much or very much improved, compared to 0 of 23 in the control waiting list. For the CBT group, the mean score on the primary self-report measure for hoarding symptoms (the Savings Inventory – Revised (SI-R)) decreased by an average of 15% from baseline; participants on the waiting list showed virtually no reduction in hoarding symptoms. After 12 weeks, patients in the waiting list group were offered CBT. At session 26, 71% of patients showed improvement on the therapist's global improvement rating scale. Therapy gains were maintained up to 1 year later and 62% of patients who completed the original study were rated as much or very much improved.

An Australian study delivered a brief (12-week) group CBT based on the Steketee & Frost treatment model (Moulding Reference Moulding, Nedeljkovic and Kyrios2017). It recruited 77 participants with hoarding disorder into 12 group programmes, and each group received 12 sessions of treatment that included psychoeducation, skills training (organisation and decision-making), direct in-session exposure to sorting and discarding, and cognitive and behavioural techniques to support out-of-session sorting, discarding and non-acquiring. Self-report measures were used post treatment and at 12-week follow-up. Hoarding symptoms as measured on the SI-R reduced significantly, with large effect sizes reported in total and across all subscales. Moderate effect sizes were also reported for hoarding-related beliefs (emotional attachment and responsibility) and depressive symptoms. Of the 41 participants who completed post-treatment questionnaires, 34% were calculated to have clinically significant change.

Specialised CBT with older people (Ayers Reference Ayers, Najmi, Howard, Frost and Steketee2014) has yielded mixed results. Ayers et al (Reference Ayers, Wetherell and Golshan2011) examined the response of 12 older adults to 26 sessions of Steketee & Frost's manualised CBT. There were only three responders and benefits had been lost by the 6-month follow-up. In a pilot study involving 11 elderly patients (Turner Reference Turner, Steketee and Nauth2010), 6 completed the CBT programme with modest improvement. Ayers et al (Reference Ayers, Najmi, Howard, Frost and Steketee2014) further investigated the feasibility of an age-adapted manualised behavioural treatment for geriatric hoarding in 11 participants who received 24 individual sessions of cognitive rehabilitation and exposure to discarding/not acquiring. At the end of treatment, eight were classified as responders and three as partial responders. Combination therapy doubled the response rates compared with cognitive rehabilitation alone.

Novel and pioneering approaches for hoarding disorder are emerging, albeit in need of further research. These include web-based group CBT (Muroff Reference Muroff, Steketee and Himle2010a), home-based webcam trials (Muroff Reference Muroff and Steketee2010b) and a bibliotherapy self-help group (Frost Reference Frost, Pekareva-Kochergina and Maxner2011b).

Pharmacological interventions

Antidepressants

Results from clinical series of patients with OCD suggest that those with hoarding symptoms or with higher scores on the hoarding factor dimension are less responsive to treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (Black Reference Black, Monahan and Gable1998; Winsberg Reference Winsberg, Cassic and Koran1999). It is hypothesised that neurobiological differences in non-hoarding patients could account for this. In one case series, only 1 of 18 people with hoarding disorder treated with a variety of SSRIs showed adequate response and 9 showed no response at all (Winsberg Reference Winsberg, Cassic and Koran1999).

In a prospective study 79 patients with OCD, 32 of whom had hoarding disorder, were treated openly with paroxetine for 10–12 weeks with no other intervention during the study period. Both hoarding and non-hoarding participants improved significantly with treatment, with nearly identical changes in scores on the Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD), Hamilton Anxiety Scale (Ham-A) and Global Assessment Scale (GAS). Hoarding symptoms improved as much as other OCD symptoms, indicating paroxetine produced similar benefits for both hoarding and non-hoarding patients with OCD, although improvement was modest in both groups (Saxena Reference Saxena, Brody and Maidment2007b).

Recent pharmacotherapy research has incorporated more robust hoarding psychometrics with encouraging results. Serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) therapy for individuals with a primary diagnosis of hoarding disorder has led to symptom improvement comparable to that seen with CBT. Twenty-four patients meeting DSM-5 criteria for hoarding disorder were treated with venlafaxine extended-release for 12 weeks, and no other psychotropic medications or psychological therapy were permitted during the study. Self-report measures were administered before and after treatment. Twenty-three of the 24 patients completed treatment. Hoarding symptoms improved significantly, with a mean 36% decrease in UCLA Hoarding Severity Scale (UHSS) scores and a mean 32% decrease in SI-R scores. Sixteen of the 23 completers (70%) were classified as responders to venlafaxine extended-release (Saxena Reference Saxena and Sumner2014).

Psychostimulants

Individuals with hoarding disorder self-report and objectively present with attention difficulties that may contribute to problems with decision-making and lead to an accumulation of clutter (Frost Reference Frost, Steketee and Tolin2011a). Results of an open-label case series trialling a 4-week course of methylphenidate in four patients with hoarding disorder and moderate attention problems showed mixed results for both hoarding symptoms and attention; gains were modest and there was unanimous discontinuation of methylphenidate because of poor tolerability. Nevertheless, the trials showed that self-reported and objective inattention reduced with treatment without new-onset psychiatric symptoms (Rodriguez Reference Rodriguez, Bender and Morrison2013). However, limitations of the study (small number of patients, scales used, concomitant psychotropics, etc.) were such that caution should be exercised when looking at results.

Ethical considerations in the treatment of hoarding disorder

Clinicians hold responsibility to maintain confidentiality, reduce infringement of privacy and only disclose information if the patient gives consent. However, some situations warrant breaching confidentiality, for instance reporting suspected abuse of dependents or self-neglect, immediate risk of serious harm or inability to remain safely in the community. These are not uncommon scenarios in cases involving hoarding disorder (Gibson Reference Gibson, Rasmussen and Steketee2010).

A multiagency approach is paramount in appraising the situation and responding in a proportionate manner to the risks identified, but again the patient's privacy must be considered and consent obtained. Increasing resources in services that provide support to individuals with hoarding problems may reduce the need for compulsory solutions, which can lead to increased resistance and mistrust in service providers (Gibson Reference Gibson, Rasmussen and Steketee2010). Development of local protocols can offer clear guidance for partnership work using an outcome-focused and solution-based model (London Borough of Merton 2014).

The Equality Act and DSM-5

The legal implications of the inclusion of hoarding disorder as a distinct diagnosis in DSM-5 in 2013 are far reaching and starting to become clearer.

The Equality Act 2010 introduced the concept of ‘discrimination arising from disability’, extending its protection to prohibit indirect discrimination as a result of disability and requiring that reasonable adjustments be made for disabled people. As hoarding disorder is now a diagnosis in its own right, public bodies are required to work to eliminate discrimination in the field of housing and eviction of those with the disorder and to foster good relations.

This is particularly relevant in some cases where a tenant with hoarding problems is facing eviction proceedings by their landlord (e.g. local authority, housing association, council) because of the cluttered and sometimes squalid state of the property. In these cases, it is paramount that an assessment for disability under the Equality Act be carried out by an experienced assessor, ideally with experience in hoarding cases. A person is considered ‘disabled’ under the Act if they have a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on their ability to carry out normal daily activities.

Weiss & Khan (Reference Weiss and Khan2015) document similar issues related to various disability laws in the USA: most disputes about hoarding between landlords and tenants are now handled without recourse to formal litigation and they note that there is little case law to quote. They also point out that hoarding disorder differs from many psychiatric disorders as it may affect others in terms of public health, personal safety and safeguarding and it may be subjected to various forms of legislation. A balance between the rights of individuals and those of the community will therefore need to be found.

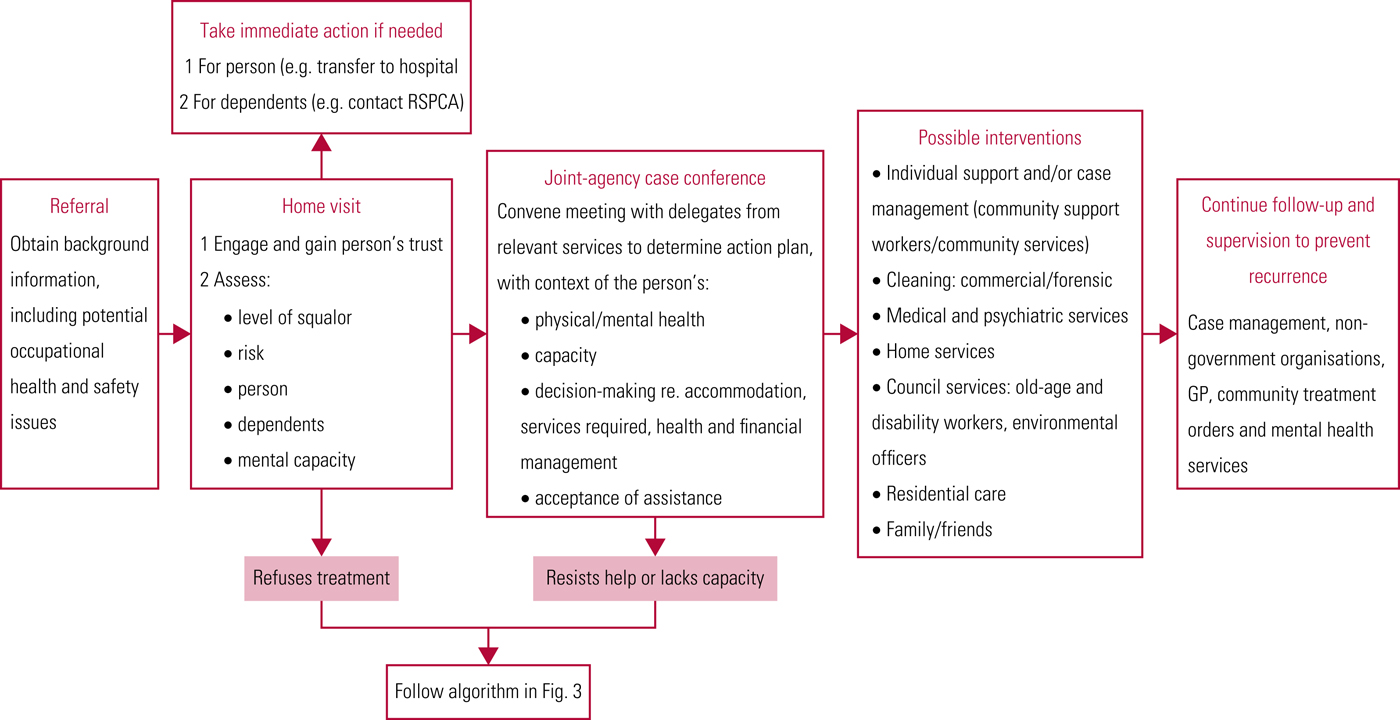

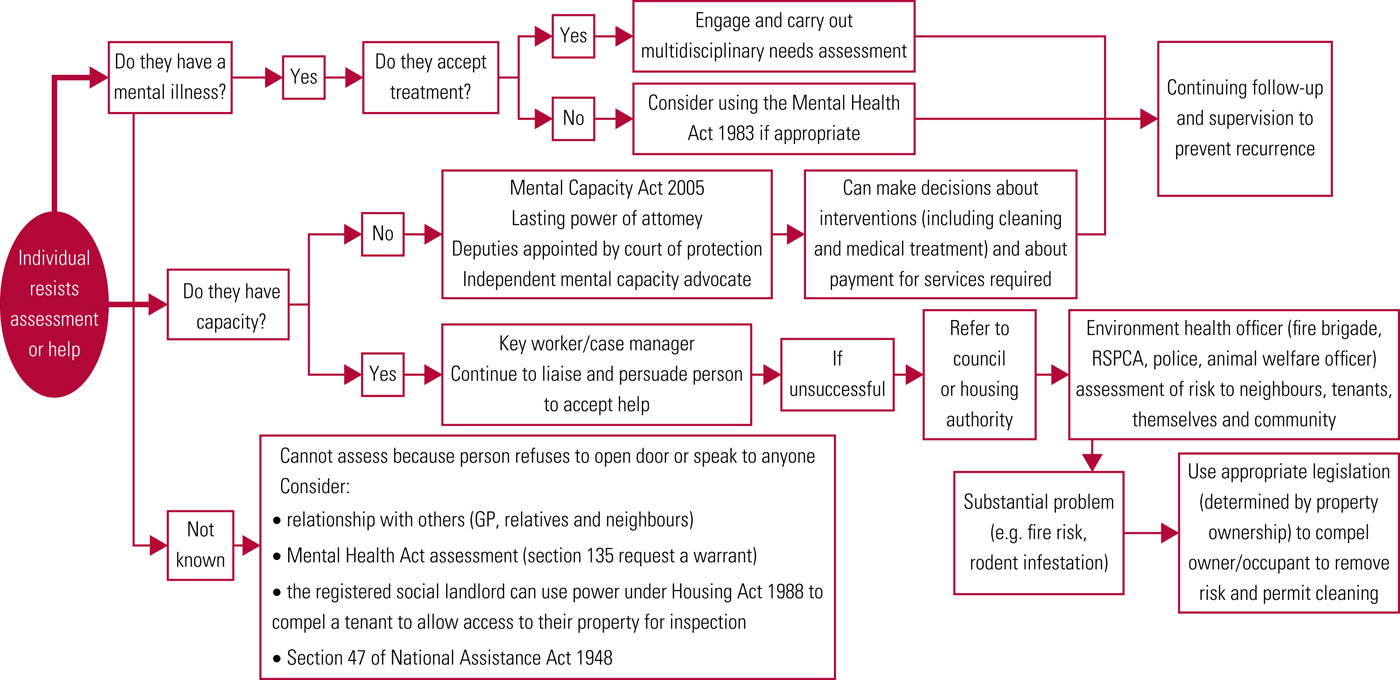

Figures 2 and 3 offer guidance on interventions from the point of referral and on the myriad challenges that the clinician might face.

FIG 2 Assessment and management of people living in squalor. RSPCA, Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Reproduced from Lopez Gaston et al (Reference Lopez Gaston, Kiran-Imran and Hassiem2009) and based on Northern Sydney Severe Domestic Squalor Working Party (2005), with permission.

FIG 3 Assessment algorithm for individuals living in squalor and resisting treatment. GP, general practitioner; RSPCA, Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Reproduced from Lopez Gaston et al (Reference Lopez Gaston, Kiran-Imran and Hassiem2009) and based on Northern Sydney Severe Domestic Squalor Working Party (2005), with permission.

Conclusions

Hoarding disorder is recognised as an independent diagnostic category in DSM-5 as well as ICD-11. Individuals with ‘extreme’ collecting behaviour could also fulfil the diagnostic criteria, but false positives are unlikely among normative collectors. The prevalence of hoarding disorder in the general population is 2–6%; the condition has high levels of comorbidity, primarily with anxiety disorders and depression, and has extensive negative consequences not only for the individual but also for significant others and society at large.

Hoarding can also present as a symptom in the context of other mental health disorders, such as dementia and schizophrenia, and genetic or developmental disorders, but the quality of the behaviour differs significantly from hoarding disorder. Neurophysiological, genetic and neurocognitive patterns have been identified in people with hoarding disorder but more research is required, which will be highly specific in the context of the newly developed diagnostic criteria.

Treatment for this condition, although labour intensive, has demonstrated good outcomes with both pharmacological and psychological interventions. Older adults remain more resistant to treatment, which makes early diagnosis a necessity. Although more trials are needed, existing results are promising.

Ethical and moral issues are raised in the appraisal of this condition and its impact on individuals and society. Consequently, treatment and interventions require a multiagency approach and the development of local protocols.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 With regard to hoarding disorder:

a it is currently classified as a standalone diagnosis both in DSM-5 as well as in ICD-11

b it is a type of OCD (obsessive–compulsive disorder)

c it is rarely associated with other psychiatric or neurological conditions

d lack of insight is a necessary symptom for the diagnosis

e it is the same as Diogenes syndrome.

2 Hoarding:

a is exclusively present in hoarding disorder

b can be a symptom of hoarding disorder as well as a manifestation of other psychiatric or neurological conditions

c is a term used as a synonym of collecting

d is always pathological

e is always associated with excessive acquisition.

3 Diagnostic criteria for hoarding disorder include:

a occasional difficulties discarding possessions

b the individual experiences significant distress when acquiring possessions

c the hoarding results in active living areas becoming so cluttered that their intended use is substantially compromised

d the behaviour and associated consequences tend not to impair the person's quality of life

e the behaviour must be the result of a medical condition such as brain injury or cerebrovascular disease.

4 With regard to animal hoarding:

a is defined by having 10 or more animals at home

b the diagnosis requires a PET scan

c it is currently classified as a subtype of hoarding disorder in the DSM-5

d animal hoarders fail to provide minimal standards of nutrition and sanitation

e the diagnosis is strongly related to the size and number of animals involved.

5 As regards treatment of hoarding disorder:

a CBT has been shown to be ineffective

b older patients have better outcomes

c more research is necessary to ascertain the efficacy of pharmacological treatments

d psychostimulants have been conclusively proven to be effective

e a multi-agency approach is not necessary.

MCQ answers

1 a 2 b 3 c 4 d 5 c

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.