1. Introduction

Transgender people (also called trans people) experience an incongruence between their birth assigned sex and their own sense of gender identity [Reference Winter, Diamond, Green, Karasic, Reed and Whittle2]. Incongruence can be social, - how others perceive the person based on their birth assigned sex and/ or physical - between an individual`s self-identity and their primary or secondary sex characteristics [Reference Winter, Diamond, Green, Karasic, Reed and Whittle2]. Trans people living in a largely gender-binary society experience significant levels of social rejection, discrimination, often resulting in poor physical and mental health [Reference Bockting, Miner, Swinburne Romine, Hamilton and Coleman3]. Transgender people are a very diverse group, which includes individuals who live with their gender incongruence without transition, others who decide on social transition only without accessing specialist gender services and individuals who purchase their own hormones online [Reference Winter, Diamond, Green, Karasic, Reed and Whittle2]. This creates challenges in relation to estimating population sizes and studies on the experiences of individuals who identify as transgender, gender non-conforming or gender-questioning are usually focused on gender affirming treatments from health services, mostly because these individuals are reached relatively easily. Published population studies focused on questioning participants from the general population about their identity report estimates of 0.5% [Reference Conron, Scott, Stowell and Landers4] to 1.3% [Reference Clark, Lucassen and Bullen5] for those who are male assigned at birth, while estimates of 0.4% [Reference Conron, Scott, Stowell and Landers4] to 1.2% [Reference Clark, Lucassen and Bullen5] are reported for those who are female assigned at birth. Using the lower estimates of these studies as an overall mean and extrapolating these figures to a global population of 5.1 billion [Reference Winter, Diamond, Green, Karasic, Reed and Whittle2], calculate a figure of 25 million transgender individuals worldwide.

Gender services across Great Britain have seen a 240% increase in gender-affirming treatment referrals over the past five years [Reference Torjesen6], similar to trends in most developed countries. Despite this, there is no consensus on optimal assessment of psychological functioning and mental health of individuals requesting gender affirming treatments [Reference Keo-Meier and Fitzgerald7]. The assessment of personality disorders for those seeking gender-affirming treatment is regarded by some as critical to treatment planning and prognosis on the outcome of medical and surgical interventions [Reference Duisin, Batinic, Barisic, Djordjevic, Vujovic and Bizic8].

Individuals who experience distress related to their sex assigned at birth can access specialist gender services for psychological, medical and/or surgical interventions. According to the current World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidance [Reference Coleman, Bockting, Botzer, Cohen-Kettenis and DeCuypere9], anyone seeking gender-affirming treatments (for example hormones or surgical procedures) should complete a comprehensive assessment process which includes a psychological/ psychiatric assessment [Reference Fraser10]. Psychiatric assessment in this population has historically consisted of detailed clinical interviews.

1.1 Gender Dysphoria

Gender dysphoria is considered a psychiatric diagnosis as part of the current version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [11] and International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) [12]. This is the subject of ongoing debates attracting various opinions; from welcoming mental health professionals as part of responsible transgender treatments [Reference Selvaggi and Giordano13] to removing gender dysphoria from the category of psychiatric diagnoses [Reference Richards, Arcelus, Barrett, Bouman, Lenihan and Lorimer14]. Proposed changes in the ICD-11 include a change in terminology from transsexualism categorised under the mental health section to gender incongruence of adolescence and adulthood under the categories of sexual health [Reference Thomas, Pega, Khosla, Verster, Hana and Say15].

1.2 Personality assessment

Personality incorporates traits or constructs that differentiate individuals from others [Reference Krueger, Skodol, Livesley, Shrout and Huang16], as well as intra-psychic processes which enable individuals to achieve valued and need-fulfilling life-tasks [Reference Westen, Shedler and Bradley17]. These life tasks include creating a working model of the self, relating well to other people and reaching occupational goals [Reference Krueger, Skodol, Livesley, Shrout and Huang16]. The assessment of personality and personality traits using questionnaires for this purpose is undertaken in a variety of occupational, legal and clinical settings. In clinical environments, standardised personality assessments can be a useful guide for selecting treatments for individuals based on their personality traits. For example, cognitive behaviour therapy may be a treatment option more suitable to some individuals with specific personality traits while others might prefer a different modality.

1.3 Personality disorder assessment

Difficulties in relation to achieving adult life tasks are often associated with personality pathology [Reference Skodol, Gunderson, Shea, McGlashan, Morey and Sanislow18]. Personality disorders are not simply defined as clinically significant extreme personality traits, rather the mechanism that is dysfunctional is stopping the individual from functioning adaptively in society [Reference Livesley and Jang19]. Personality disorders are pervasive and ingrained [11], however more recent evidence highlights that personality status can change in response to treatment [Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj and Ranger20]. Since the formulation of DSM-III [11], personality disorders were given a separate axis in the classification which consisted of 11 categories. This categorical system of classifying personality disorders using heterogenous descriptions did not work well in practice and dimensional models based on personality traits rather than behaviours were considered [Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj and Ranger20]. A dimensional system considers personality on a continuum with normal variations on one end and what is considered a personality disorder at the extreme end of the continuum [Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj and Ranger20]. The assessment of personality disorders is focused on the functional impact and has evolved over time from a categorical approach in which clinicians attempted to match individuals to multiple categories to a more dimensional approach but agreement between different assessment approaches continues to be an issue. Other concerns related to the stability of current assessment methods, definitions of severity of personality disorders and information sources used for the assessment are unresolved [Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj and Ranger20]. Personality is generally assessed using a combination of self-report questionnaires and a structured clinical interview [Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj and Ranger20]. There are numerous available clinical interview schedules and questionnaires for the assessment of personality disorders, but unfortunately cross-instrument reliability is very poor, which is largely related to the criteria for different personality disorder diagnoses and overlap between categories, often leading to multiple diagnoses [Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj and Ranger20]. The reported prevalence of personality disorders in those seeking gender-affirming treatments ranges from 4.3% [Reference Fisher, Bandini, Casale, Ferruccio, Meriggiola and Gualerzi21] to 81.4% [Reference Meybodi, Hajebi and Jolfaei22], perhaps reflecting the disparate cultural contexts (Italian and Iranian), social norms and inherent difficulties in conducting diagnostic assessments for personality disorders. The diagnosis of personality disorders remains controversial [Reference Lewis and Grenyer23], argued by some as carrying more stigma and shame than for other psychiatric diagnoses [Reference Catthoor, Feenstra, Hutsebaut, Schrijvers and Sabbe24, Reference Magallón-Neri, Forns and Canalda25] and consequently impacting on service access [Reference Adebowale26–Reference Latalova, Ociskova, Prasko, Sedlackova and Kamaradova28]. Under the current World Professional Transgender Health (WPATH) guidance [Reference Coleman, Bockting, Botzer, Cohen-Kettenis and DeCuypere9], access to gender-affirming treatments is the treatment of choice for individuals experiencing gender related distress. While most individuals experience positive changes following hormonal and or surgical interventions, between 1 and 2% of individuals expressed regret and a further 1% attempt suicide [Reference Michel, Ansseau, Legros, Pitchot and Mormont29]. Some studies have delayed or excluded individuals with significant psychopathology from accessing hormonal or surgical interventions [Reference Smith, Van Goozen and Cohen-Kettenis30], while others have suggested a link between post -operative dissatisfaction and pre-operative psychopathology [Reference De Cuypere, Elaut, Heylens and Van Maele31].

1.4 Objectives

Psychometric assessment tools are commonly used in clinical practice to assess personality in individuals requesting gender-affirming care. However, no formal guidelines for interpreting test data for transgender individuals exist [Reference Keo-Meier and Fitzgerald7]. Other authors [Reference Campbell, Ocampo, Rorie, Lewis, Combs and Ford-Booker32, Reference Heaton, Taylor and Manly33] suggest that minority individuals can be overly pathologized in psychometric tests using normative data. Some of the psychometric assessment tools, for example the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI-2) [Reference Butcher34], are scored on gender-based norms. It is unclear whether individuals should be evaluated based on their assigned sex at birth, self-identified gender or both and further questions arise for individuals identifying outside the gender binary. To date, the accuracy of psychometric assessment tools for personality disorder assessment in this population has never been examined in a systematic review. In view of concerns about personality disorders as poor prognostic factors and potential reasons for denying access to gender-affirming treatments, we conducted a systematic review.

Aims:

To review:

• What psychometric tests (interventions) and reference tests (comparisons) are used to diagnose personality disorders (outcome) in adolescents and adults who request gender-affirming treatments (population)?

• How accurate are psychometric tests for diagnosing personality disorders compared to reference tests in adolescents and adults requesting gender-affirming treatment.

2. Method

2.1 Protocol and registration

This review is based on the protocol ‘Accuracy of psychometric tools in the assessment of personality in adolescents and adults requesting gender realignment: protocol for a systematic review [Reference Lehmann and Leavey1]. The protocol is accessible via Prospero International prospective register of systematic review: CRD42017078783; available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID42017078783.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

Diagnostic accuracy assessment studies are commonplace in physical medicine but much less so in mental health practice. Over the past decade the reporting of diagnostic accuracy studies has been under scrutiny and calls for greater transparency in the reporting of studies have led to the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) [Reference Bossuyt, Reitsma, Bruns, Gatsonis, Glasziou and Irwig35]. In the case of this review, the STARD standards were not available at the time of reporting of included studies. Accuracy broadly refers to the agreement between the test under study and the reference or standard test [Reference Flahault, Cadilhac and Thomas36]. Accuracy refers to high sensitivity, the chances that the test outcome is positive in someone who has the condition, while specificity refers to the probability that the test outcome is negative in someone who does not have the condition [Reference Knottnerus and Muris37]. The reference test is the gold standard test available to identify the outcome (personality disorder) in the population (adolescents and adults requesting gender affirming treatments). Tests with 100% sensitivity and specificity are very rare thus the term reference standard rather than gold standard is more appropriate [Reference Knottnerus and Muris37]. A gold standard in personality disorder assessments is rare [Reference Tyrer, Coombs, Ibrahimi, Mathilakath, Bajaj and Ranger20]. Challenges in assessment can be linked to the classification of personality disorders, poor inter-rater reliability in clinical assessments [Reference Livesley and Larstone38] and evidence of personality status as unstable [Reference Shea, Stout, Gunderson, Morey, Grilo and McGlashan39] rather than fixed over a lifespan. And in the absence of other alternatives, clinical assessments were used as the reference test for the review. Psychometric tools for the assessment of personality disorders were used as index test in this review.

The timing of index and reference tests at various points of contact with specialist gender services (e.g. on assessment, following physical interventions) was considered in the review. Children up to the age of 12 years old were excluded from the review for several reasons. While children, adolescents and adults seek gender affirming treatments based on current WPATH guidance [Reference Coleman, Bockting, Botzer, Cohen-Kettenis and DeCuypere9], the assessment of personality disorders tends to focus on adolescents and adults [Reference Skodol, Johnson, Cohen, Sneed and Crawford40].

2.3 Information sources

An electronic literature search was conducted using Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to December 2018) • Ovid MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (December 2018), Embase (1980 to December 2018; Ovid), PsycINFO (1887 to December 2018; EBSCOhost), PsycARTICLES (1894 to December 2018; EBSCOhost) and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR; latest issue, The Cochrane Library). The initial search strategy initially was adapted for individual databases. Searches were limited to the years following the publication of the first WPATH standards in 1979. Language limits were not applied to the searches and translations were sought where possible. As previous searches did not identify any studies clearly identified as diagnostic accuracy studies, a narrow search for study type was not possible.

Example of search strategy

(1) exp Gender Identity/

(2) exp Gender Dysphoria/

(3) exp Transsexualism/

(4) exp Transgender Persons/

(5) gender variance mp.

(6) gender fluid mp.

(7) sex change mp.

(8) gender change mp.

(9) Gender identity mp.

(10) Gender dysphoria mp.

(11) Transsexualism mp.

(12) Transgender mp.

(13) 1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12

(14) exp Mental Health/

(15) exp Psychological Tests/

(16) psychological needs.mp

(17) exp Mental Health services/

(18) Mental Health.mp

(19) Psychological Test*. Mp

(20) exp Personality/

(21) exp personality disorder/

(22) personality mp.

(23) personality disorder mp. 24) 14 OR 15 OR 16 OR 17 OR 18 OR 19 OR 20 OR 21 OR 22 OR 23 25) 13 AND 24 26) exp animals/ not humans.sh 27) 25 NOT 26 28) limit (24) to (yr= “1979- Current” and (“all adult (19 plus years)” or “adolescent (13–18 years)”)) (Table 1)

Table 1 PRISMA Flow Diagram [Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman41].

2.4 Data collection process

Both review authors independently screened titles and abstracts returned through the searches against the inclusion criteria. Full text studies were obtained if the titles and abstract met the inclusion criteria or if there was uncertainty. Both reviewers screened full text articles and made decisions about the inclusion of the study. Additional information was sought from the authors if there were uncertainties regarding eligibility of the studies. One of the studies was translated from Dutch into English for further review but did not meet inclusion criteria on closer inspection. Both reviewers independently used a standardised tool to extract the information [Reference Campbell, Klugar, Ding, Carmody, Hakonsen and Jadotte42] and completed critical appraisal checklists and then compare findings. Any disagreements were resolved through further discussion.

Data items included inclusion/exclusion criteria for each study, sample size, participant demographics, study methodology, index test description, reference test description, geographical location of data collection, setting of data collection, persons executing and interpreting index tests, persons executing and interpreting reference tests and index/ reference time interval (and treatments carried out in between).

2.5 Risk of bias assessment

The QUADAS-2 revised tool [Reference Whiting, Rutjes, Westwood, Mallett, Deeks and Reitsma43] was used to assess the methodological quality of each included study in relation to risk of bias in the selection of patients, patient flow, the conduct and interpretation of the index test and the conduct and interpretation of the reference test. The QUADAS-2 tool was piloted prior to use. Both authors independently completed risk of bias assessments on each included study. Disagreements were resolved through further discussion.

3. Results

3.1 Study selection

Overall 13,849 studies were independently screened. By the screening of titles and abstracts 13,824 studies were excluded, while 25 studies were screened for further detailed analysis, from which 23 studies did not meet the eligibility criteria as the studies did not compare a psychometric tool for personality disorder assessment with an index test. Only two studies conducted in 1993 [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44] and 2000 [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45] met inclusion criteria for the review (Table 2).

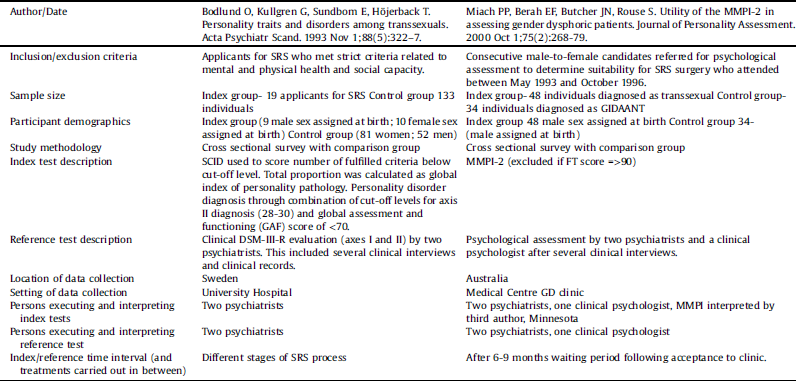

Table 2 Study characteristics of included studies.

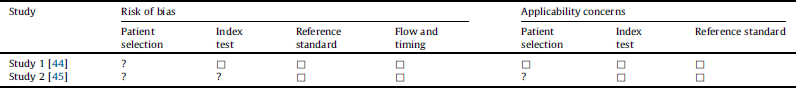

3.2 Risk of bias assessment- study 1 [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44]

The first study used a total population sample of all individuals requesting gender-affirming care in a Swedish region of 2.5 million inhabitants. All participants met the then criteria for transsexualism to access gender affirming treatments under the then DSM-III-R [Reference American Psychiatric Association46]. Participants were administered index and reference tests at different stages of gender affirming care and included individuals who were established on hormone treatments and individuals who had already completed gender affirming surgical treatments. While it was believed that personality profiles remain stable over a lifetime [Reference Spiro, Butcher, Levenson, Aldwin and Bosse47], more recent studies have found positive changes in functioning following testosterone therapy [Reference Keo-Meier, Herman, Reisner, Pardo and Sharp48]. Comparing individuals at different stages may have impacted on the results of the study. The study [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44] used the Swedish version of the SCID screen [Reference Ekselius, Lindström, von Knorring, Bodlund and Kullgren49]. The SCID includes 124 questions, with 103 criteria for the assessment of personality disorders. Authors used the SCID to score the number of fulfilled criteria to describe personality traits below cut-off level and to make diagnoses of personality disorder based on DSM-III-R [Reference American Psychiatric Association46] criteria. The authors set additional criteria for the diagnosis of personality disorder by combining cut-off levels for axis II diagnosis (28–30) with a global assessment of functioning (GAF) score [Reference Jones, Thornicroft, Coffey and Dunn50]of <70. The global assessment of functioning was used in this context as an additional layer for diagnosis and measure for social and occupational functioning of participants. The Global Assessment of Functioning is a numerical scale completed by a clinician, which rates the social, psychological and everyday functioning of an individual [Reference Hall51]. The maximum score which can be attained is 100, indicating the best possible functioning. Two psychiatrists conducted several clinical interviews and reviewed clinical records before making a diagnosis related to personality difficulties based on the DSM-II-R [Reference American Psychiatric Association46]. Based on standards at the time, clinician diagnosis based on all available data [Reference Skodol, Johnson, Cohen, Sneed and Crawford40] was the accepted diagnostic process. It is unclear whether the two psychiatrists were aware of the results of the index test prior to conducting the reference test. Nineteen participants completed the index and reference standard tests, but it is unclear at what point the tests were completed. Three patients failed to meet other requirements for access to gender-affirming treatments (age, immaturity and alcohol problems) and were excluded. All participants who completed the index and reference test were included in the analysis. The study also included a control group who only completed the index test.

3.3 Risk of bias assessment- study 2 [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45]

The second study enrolled a consecutive sample of males assigned at birth who were referred to a national centre for assessment. It is not stated why only males assigned at birth were included in the study, but the authors differentiate between males assigned at birth meeting criteria for transsexualism under DSM-III-R [Reference American Psychiatric Association46] and those meeting non transsexual gender dysphoria (GIDAANT) under the same criteria. All participants completed index tests on admission to the service and reference tests were completed after 6 months waiting period following admission to the service. As the service accepts referrals for surgical gender affirming procedures it is unclear if any or all participants were already established on hormone treatments prior to admission to the service. The MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] was administered to all 86 individuals at initial assessment. MMPI-2 sheets were scored and analysed independently by one of the authors in Minnesota. The MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] was completed on admission to the centre while the reference standard was undertaken after a period of waiting following the admission. The threshold for scoring the MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] was specified and those with a scale F T score of 90 or above were excluded from the study. The F Score is related to atypical responses on the MMPI-2 and a score of 90 or above creates questions in relation to the truthfulness of responses [Reference Wygant, Sellbom, Ben-Porath, Stafford and Freeman52]. Participants were scored against their sex assigned at birth. Two psychiatrists and one clinical psychologist independently assessed participants. During a subsequent team conference all information was reviewed and diagnoses in relation to a personality disorder were made based on DSM-III-R standards [Reference American Psychiatric Association46]. Disagreements were resolved through further team discussion and through collecting new information to aid the diagnostic process. This process appears to have been conducted independently from the index test, which was scored and processed elsewhere. Four patients were excluded from the data analysis due to MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] scale F T scores of 90 or above. The MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] includes F scale items to detect unusual and potentially untruthful ways of responding to test items [Reference Wygant, Sellbom, Ben-Porath, Stafford and Freeman52]. The MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] was conducted at admission to the programme, while psychological testing was conducted after completion of a waiting period of 6–9 months after admission to the programme with an appropriate interval between index and reference standard tests (Tables 3–5).

Table 3 Risk of Bias and Applicability Judgments based QUADAS-2 [Reference Whiting, Rutjes, Westwood, Mallett, Deeks and Reitsma43].

□ = low risk; ☹ = high risk; ? = unclear risk.

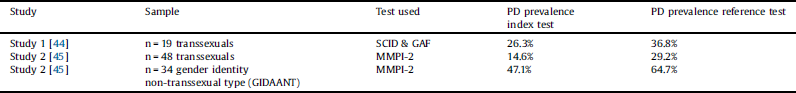

Table 4 Prevalence of personality disorders.

Table 5 Accuracy, Sensitivity and specificity of index tests compared to reference standards.

3.4 Prevalence of personality disorders

We only included results which were in keeping with the population in this review and therefore results related to a non-representative control group of individuals selected from the general population were not included [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44]. In both studies, index tests detected less individuals with personality disorders compared with the reference standards. A significantly higher number of individuals in study 2 [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45] belonging to the gender identity non-transsexual type group (GIDAANT) were reported to have personality disorders. Accurate diagnostic assessment can be made in the context of accepted criteria [Reference Knottnerus and Muris37], which for both studies relate to a binary measure of absence or presence of personality disorders. Diagnosis of personality disorder was based on an agreed reference standard [Reference American Psychiatric Association46]. We calculated sensitivity and specificity for both studies. Both index tests were over 82% accurate in detecting personality disorders in the three groups. Neither of the index tests created false positives thus a diagnosis of personality disorder in individuals who do not have a personality disorder based on the reference test. While the SCID & GAF [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44] and MMPI-2 [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45] showed a sensitivity of over 72% in identifying true positives meaning individuals who are diagnosed with a personality disorder on index and reference test, the sensitivity of the MMPI-2 [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45] in the transsexual group was only 50%. The interpretation of these results however needs to be completed in the context of other factors.

4. Discussion

This is the first systematic review on the assessment of personality disorders in gender reassignment. Given the rapid increase in people seeking gender-affirming treatment across Western, developed countries, it is perhaps alarming that we found only two studies and even these have considerable limitations.

In the first study [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44], all participants met very stringent criteria for transsexualism [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45], functioned well socially and showed no signs of severe mental illness. The authors acknowledge that the sample represents a carefully selected group of individuals as a large proportion requesting gender affirming treatments are excluded because of their mental health, physical conditions or poor social functioning [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44]. There is no information on the baseline measures of all participants. It is unclear how many individuals were new to the service; how many had been taking hormonal interventions and how many were waiting or had completed their surgical transition. This is an important issue, as hormonal treatment has shown to improve functioning in other studies [Reference Keo-Meier, Herman, Reisner, Pardo and Sharp48].

The second study [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45] used a representative sample, but only focused on males assigned at birth. This relates to the study differentiating between males assigned at birth meeting transsexual criteria and those meeting gender identity disorder non- transsexual type (GIDAANT) criteria [Reference American Psychiatric Association46]. The difference between criteria for diagnosis of transsexual compared to GIDAANT is largely related to persistent pre-occupation for at least two years with wanting to get rid of sex characteristics assigned at birth [Reference American Psychiatric Association46]. Those meeting GIDAANT criteria, met criteria for discomfort related to sex assigned at birth without the desire to want rid of sex characteristics assigned at birth.

The SCID screen used in the first study [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44] is a self-report questionnaire containing 124 questions requiring yes or no responses. Participants were at different stages of their gender affirming care when they completed the SCID screen. It is difficult to known how the timing of the SCID screen impacted on the results. The addition of the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) criteria was used to reduce over inclusiveness in the diagnosis of personality disorder. While the GAF has been described as a valid and reliable instrument [Reference Von Korff, Andrews, M, Regier, Narrow and Kuhl53] it has been excluded from the most recent DSM-5 edition as an inadequate instrument to assess psychiatric functional impairment [Reference Gold54]. The exclusion was based on lack of conceptual clarity of the GAF, questionable psychometric properties of the GAF and its reliance on appropriate training of the clinician to ensure reliability and validity of the instrument [Reference Gold54]. In the GAF any impairments in functioning related to physical or environmental factors are not considered [Reference Gold54]. The GAF`s conflation of symptom severity is often not congruent with levels of experienced impairment of functioning [Reference Gold54]. This could have created GAF scores < 70 suggestive of significant impairment when this was not actually the case. Furthermore, physical factors due to gender affirming treatments or stressful environmental factors which may have been experienced by some individuals were not reflected in the scoring system. It is therefore difficult to know how stage of gender affirming care impacted on the GAF score.

The MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34], a 567-item questionnaire administered by a clinician is the most widely used questionnaire for the assessment of personality [Reference Spiro, Butcher, Levenson, Aldwin and Bosse47], however it is viewed as a poor assessment tool for the assessment of personality disorders [Reference Derksen and Butcher55]. It is unclear why the MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] was chosen for this was study other than that it was part of the assessment procedure of the clinic at the time. The MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] was scored independently based on male normative data. Other research has highlighted that those in the earlier phase of their transition process show higher scores on the MMPI-2 [Reference Gómez-Gil, Vidal-Hagemeijer and Salamero56], with testosterone treatment reducing MMPI-2 scores in one study [Reference Keo-Meier and Fitzgerald7]. This contrasts with prior studies which suggested that MMPI-2 results remain stable over time even in individuals who complete intensive psychotherapy [Reference Spiro, Butcher, Levenson, Aldwin and Bosse47]. The MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] is based on male or female normative data. Male and female norms for the MMPI-2 [Reference Butcher34] were derived from a representative sample of the cisgender (not transgender) population and thus normative data for those requesting gender affirming care does not exist. It has been suggested that cultural variables can impact MMPI-2 scores [Reference Keo-Meier and Fitzgerald7] with elevation to the psychopathic deviate scale caused by lack of acceptance of transgender people in society [Reference de Vries, Doreleijers, Steensma and Cohen‐Kettenis57] or even experienced transphobia.

Reference tests in both studies consisted of detailed psychological and psychiatric assessments by a team of clinicians. It is unclear whether clinicians in the first study [Reference Bodlund, Kullgren, Sundbom and Höjerback44] were aware of the outcome of the index test prior to conducting the reference test. Given the small total sample in this study clinicians may have already been aware of the absence or presence of personality difficulties as some participants were attending the centre for many years. In the second study [Reference Miach, Berah, Butcher and Rouse45], the reference test diagnosis was based on a team consensus approach. There is a clear time interval between index and reference test. While the index test was processed and scored elsewhere it is unclear if the clinical team were aware of the results of the index test prior to conducting the reference test.

To establish the sensitivity and specificity of a diagnostic test, the prevalence of the disorder needs to be considered for sample size calculations of cases and controls to be undertaken [Reference Flahault, Cadilhac and Thomas36]. Without this knowledge it is impossible to determine whether the study population is representative of the population to which the test will be applied. It is likely that much larger sample sizes including cases and controls would have been required in both studies. While this might be true from a statistical point of view, both studies included the total sample of individuals known to their respective services at a point in time. This clearly creates a range of difficulties for anyone trying to conduct accuracy assessments of psychometric tools in this population. The prevalence of personality disorders in the population was unknown and estimates from other studies range widely [Reference Fisher, Bandini, Casale, Ferruccio, Meriggiola and Gualerzi21, Reference Meybodi, Hajebi and Jolfaei22]. Even if it was possible to calculate sample sizes of cases and controls based on prevalence figures, it may be impossible to recruit enough cases for future studies.

5. Conclusion

Reference test assessment increased the prevalence of personality disorder in both studies. While personality traits are believed to be stable over many years, it is unclear whether other factors, such as prior exposure to gender affirming treatments, cultural variables or experience of transphobia could have impacted on the index test results of both studies.

Psychometric tools continue to be used to assess personality disorders in this population, despite the absence of normative data for scoring and comparative reference tests. Thus, individuals may be excluded from accessing gender affirming treatments based on clinical practice which does not have any evidence base. There is a clear gap in our current knowledge related to the reliability of psychometric assessment tools in this population. Future studies looking at the accuracy of psychometric assessment tools require larger sample sizes and knowledge of prevalence rates of personality disorders in this population. Tests also need to be developed based on normative data for the transgender not cisgender population. The development of any new normative data in this population will be very complex due to intersectionality. Individuals requesting gender affirming treatments are not a homogenous group and may belong to multiple marginalised groups for example due to their gender identity, ethnicity, sexuality or disability [Reference Beattie and Lenihan58]. Without further research and understanding of intersectionality and cultural variables impacting on personality assessments in this population we are at risk of marginalising individuals even further.

Authorship contribution

All persons (Katrin Lehmann, Professor Gerard Leavey) who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the design of the systematic review, data collection process, analysis and interpretation, drafting and revision of this article.

Funding

Katrin Lehmann is funded through the Public Health Agency Northern Ireland Research and Development Fellowship award to undertake a PhD. No additional funding was obtained for this review.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.