In recent years, the ethnic and racial diversity of lobbyists has attracted attention from American lawmakers. In 2017, members of the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC) raised concerns over the lack of diversity among Washington lobbyists. The Caucus sent a letter to prominent trade associations requesting that they diversify their lobby staff (Wilson Reference Wilson2017). Four years later, some members of the Caucus threatened not to meet with lobbyists from firms that had not diversified their staff (Fuchs and Barròn-Lòpez Reference Fuchs and Barròn-Lòpez2021). According to Monica Almond, founder of a public relations firm that specializes in helping lobby firms to diversify, “the CBC is… losing their patience because [they have] been talking about this for decades.” There are other examples of elected lawmakers expressing interest in the characteristics of advocates. In California, the leaders of six legislative caucuses sent a letter to major lobby firms and trade associations asking for demographic data related to their employees, including data on ethnicity, race, gender, and sexual orientation (Luna Reference Luna2017).

Such interest in lobbyist demographics highlights a shortcoming of scholarship on lobbying and organized interests: namely, a lack of information regarding the emergence of identity-based interest groups and historical and contemporary ethnic and racial diversity of lobbyists. To date, although there is considerable research on the gender diversity of American lobbyists (see Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022), as well as numerous case studies of civil rights advocacy efforts, scholars have paid little attention to how communities of organized interests and lobbyists have diversified along ethnic and racial dimensions. There are few estimates of how many lobbyists come from different backgrounds.

We address these shortcomings by developing a theoretical narrative linking legislative diversification to the mobilization of identity groups and clienteles of nonwhite lobbyists. We propose that the election of legislators from populations that are traditionally excluded from elite political networks encourages the mobilization of coethnic or coracial identity groups. We base our expectation on the assumption that interest groups develop alliances with particular legislators and subsidize or inform their work (as in Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006). To ensure credible spokesmanship and prevent shirking, we expect that identity groups hire lobbyists who share the identities of their group members. Finally, while the election of nonwhite people to public office may mobilize coethnic or coracial identity groups, we think that it also encourages all interests in general to hire nonwhite lobbyists. We reason that this occurs due to groups attempting to achieve access and influence (as in Wright Reference Wright1996).

To find evidence for our narrative, we turn to the American states. Our narrative requires us to examine differences in diversity between legislatures, or diversification over time within a single legislature. While comparing national legislatures or examining only the Congress may suffice, the American state legislatures are ideal for testing our narrative. The legislatures provide variation in demographic and institutional diversity across borders and time and were the first lawmaking bodies to require that lobbyists register. Using the lobbyist records that these assembles produced over several decades, we examine the mobilization of identity interests. While the records do not disclose each lobbyists’ ethnicity or race, we apply a Bayesian estimation technique developed by Imai and Khanna (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) to infer lobbyists’ identities. Then, leveraging the demographic and institutional diversity of the states, we conduct statistical analyses to test the three hypotheses implied by our narrative.

Our study provides significant new insight into the effects of legislative diversification on interest mobilization and lobbying. We find that the election of African Americans to state legislatures was correlated with the numbers of lobbyists hired by African-American identity groups. We do not find similar trends for Hispanic or Latino and Asian-American groups. Our other findings confirm that all three categories of identity groups hired lobbyists who matched the identities of their members. We then find that the election of Asian Americans to state legislatures was aligned with Asian-American lobbyists gaining more clients in general. This pattern was weaker or context-dependent for black and Hispanic or Latino lobbyists. In particular, Hispanic or Latino lobbyists gained clients in response to diversification in more Democratic legislatures. Our study is the first to provide descriptive statistics regarding the historical diversification of interest groups and lobbyists in the states and the first to test a narrative linking legislative diversification with the diversity of lobbyists.

Legislative Diversity, Mobilization, and Lobbying

We present a narrative linking historical legislative diversification with interest mobilization and lobbying. State legislatures differed from each other and over time in terms of the ethnic and racial diversity of their members, and historical diversification is proposed to have encouraged identity group mobilization. This link was based on the sharing of information. For decades, political scientists noted that lobbyists met most often with lawmakers who already favored their policy goals. Since lobbyists formed relationships with particular members of Congress and conducted policy research on their behalf, Bauer, Pool, and Dexter (Reference Bauer, Pool and Dexter1963) described lobbyists as “service bureaus.” More recently, lobbyists were said to provide a “legislative subsidy” to members of Congress (Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006).

Given the emergence of mutually beneficial relationships between interest groups and legislators, we expect that diversification among incumbent legislators encouraged coethnic or coracial identity groups to mobilize and lobby. Such groups played a role in transmitting the issue priorities and preferences of district constituents to incumbent officials. Given that districts or constituencies differed in terms of resident demographics, interests that claimed to represent residents based on identities had increased reason to lobby after the election of lawmakers who shared those identities (as in Casellas Reference Casellas2011, 51–75). Organized interests saw these legislators as natural allies who either already shared or desired information about the preferences of group members.

Alliances between legislators and interest groups with shared constituencies have been documented well at the national level. Minta (2020; Reference Minta2021) found that nonwhite members of Congress advocated especially for the positions of nonwhite identity groups. Specifically, committees with more nonwhite members were more likely to approve of bills advocated by civil rights groups such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), UnidosUS, or Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights. Moreover, the representatives of such organizations testified more frequently before committees with more nonwhite members. In these contexts, organized interest groups saw opportunities for influence within committees and mobilized accordingly, but there are yet other explanations for alliances to emerge among legislators and groups with shared identities. Minta (Reference Minta2011, 16–26) noted the potential for nonwhite legislators to ally themselves with nonwhite interests, including those based outside of their constituencies, due to perceptions of linked fate. Footnote 1 Regardless of how exactly alliances emerged, we expect identity groups to have begun to lobby once natural allies emerged within legislatures, and that alliances were based primarily on the ongoing exchange of political information for access and, ultimately, influence. Footnote 2 Legislators granted access more readily to representatives of coethnic or coracial interests so as to facilitate a legislative subsidy: “African American and Hispanic legislators… not only provide[d] special access for ethnic lobbyists, but also, like women… put new items on the legislature’s agenda” (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1993, 85).

H1: There was a positive correlation between the election of nonwhite legislators and emergence of coethnic or coracial identity interests on average, ceteris paribus.

We expect that the mobilization of ethnic or racial identity groups contributed to the diversity of communities of state lobbyists since the groups relied primarily on lobbyists who shared the identities of members. This link may have occurred for three reasons. First, identity groups hired lobbyists who were seen as credible spokespersons. Nonwhite lobbyists who represented nonwhite interests ostensibly spoke from personal experience or were expressing personal concerns, as Schlozman (Reference Schlozman, Louise and G1990) found for women’s issue groups. Given the ongoing exchange of political information for access, identity interests presumed that legislators would listen to credible-looking lobbyists more so than to non-credible-looking ones on issues of interest to ethnic or racial groups. Moreover, identity group members were more likely to support lobbyists whom they thought personally shared their interests. Hiring practices served a second purpose: reducing the potential for shirking. In general, organized interests rely on advocates whose actions they cannot monitor fully, and this allows for delegation problems (Kersh Reference Kersh2000). Footnote 3 If lobbyists who ostensibly shared the identities of group members also shared the personal interests of members, then they were more likely to work as contracted. The third reason is lobbyists simply gravitated toward representing interests that they personally cherished, including possibly by working at a discount (Berry Reference Berry1977). There is some evidence that nonwhite interests were represented in Congress primarily by nonwhite lobbyists (Laumann and Knoke Reference Laumann and Knoke1987), and we believe this trend may be detected in the states.

H2: Identity-based interest groups were more likely to be represented by lobbyists who shared the ethnic or racial identities of group members on average, ceteris paribus.

We also expect that the election of nonwhite legislators affected the clienteles of nonwhite state lobbyists. Organized interests hired lobbyists to gain access, build relationships, and achieve influence (Wright 1989). Hiring advocates for access has been documented well for particular kinds of lobbyists, including revolving-door and women lobbyists (see Blanes i Vidal, Draca, and Fons-Rosen Reference Blanes i Vidal, Draca and Fons-Rosen2012; Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022). Interest groups hired lobbyists to achieve access. By extension, they hired lobbyists who resembled their legislative targets. Interest groups understood that lobbyists build trustworthy relationships in non-workplace settings and bond with lawmakers over shared interests and identities (Diamond Reference Diamond1977; Grose et al. Reference Grose, Lopez, Sadhwani and Yoshinaka2022). They also assumed that some lawmakers may have preferred to meet with lobbyists who resembled them due to greater trust and relationship potential (Rosenthal Reference Rosenthal1993, 85), or that some might have even refused to meet with exclusively white lobbying teams. While we expect that identity group mobilization occurred due to legislators exchanging information with group representatives (since access would presumably be granted with little effort), non-identity-based groups hired coethnic or coracial lobbyists to achieve access and build relationships. Nonwhite and white lobbyists were presumably equally capable of transmitting non-identity-related policy information to lawmakers.

In a contemporary context, there is evidence that interest groups hire coethnic or coracial lobbyists to solicit particular legislators. In the words of Hispanic lobbyist Ivan Zapien, who directs the lobbying efforts of Washington firm Hogan Lovells, “[i]f you need to hire somebody to lobby the [Congressional Black Caucus] or the [Congressional Hispanic Caucus] or the Asian Pacific Caucus or whatever, like yeah, absolutely, I think it makes a hundred percent sense that you hire somebody that represents that community” (Fuchs and Barròn-Lòpez Reference Fuchs and Barròn-Lòpez2021). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, nonwhite members of Congress have expressed concerns over the ethnic or racial diversity of lobbyists. Footnote 4

H3: There was a positive correlation between the election of nonwhite legislators and the clientele totals of coethnic or coracial lobbyists on average, ceteris paribus.

Expected and Actual Trends

Our hypotheses have implications for trends in the historical diversification of communities of interest groups and lobbyists. If statistical analyses find evidence in favor of the three stated hypotheses, then there would be evidence for a linear pathway in which diversity and inclusivity (in terms of client counts) increased concurrently among lobbyists based on legislative diversification. In this process, communities of state lobbyists became more diverse in terms of advocate backgrounds, and more inclusive in that client shares of nonwhite advocates also increased relative to those of white advocates. Existing research on the emergence of women lobbyists presents just such a linear narrative. These studies suggest that women gradually entered the lobby profession (diversification) and came to represent more clients (inclusion) with time (Bath, Gayvert-Owens, and Nownes Reference Bath, Gayvert-Owen and Nownes2005; Nownes and Freeman Reference Nownes and Freeman1998), especially after the election of women to legislative office (Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022). In the case of nonwhite lobbyists, we expect the diversification of state legislatures improved both the diversity and inclusivity of communities of state lobbyists. Our first hypothesis examines the diversity of interests represented, and our second hypothesis links such diversity of interests to the diversity of advocates. Our third hypothesis examines the inclusivity of communities of lobbyists or how well the clienteles of nonwhite lobbyists compare to those of white lobbyists.

What does demographic change look like in actuality among lobbyists in America? Political scientists know practicably little about the ethnic and racial diversity of American lobbyists. While there are numerous studies of identity groups and interest mobilization generally, there are no repeated studies of diversity or inclusion within the lobbying profession. There has been no consistent polling, but scattered surveys present consistent results and suggest that diversity has improved somewhat over time. Only a few lobbyists in Milbrath’s (Reference Milbrath1963) sample of 114 Washington lobbyists were nonwhite. Three percent of the 800 lobbyists interviewed by Heinz et al. (Reference Heinz, Laumann, Nelson and Salisbury1993, 70) were nonwhite. In the mid-2000s, two hundred lobbyists active in Congress, out of thousands, appeared to be black (Birnbaum Reference Birnbaum2006). A decade later, LaPira and Thomas (Reference LaPira and Thomas2017, 52) found that about 10% of lobbyist surnames were of Asian, African, or Hispanic origin. The most recent survey, conducted in February 2021 by the Public Affairs Council, found that roughly 17% of government relations professionals were nonwhite, black, or otherwise (Horsley Reference Horsley2021). These surveys suggest that, while congressional lobbyists generally are not diverse in comparison to the U.S. population, some diversification has occurred over time. No studies examined the client shares of lobbyists based on ethnic or racial identities.

Information from state legislatures is even more limited. One estimate from Florida indicates that only 2% of the registered lobbyists are black (Jackson Reference Jackson2020). Roughly 6% of lobbyists in Indiana are nonwhite (Kinsella and Snideman Reference Kinsella and Snideman2022).

Data and Measurement

The state legislatures were the first assemblies to require that lobbyists register, and there is significant demographic and institutional variation across the states (Strickland Reference Strickland2020). Footnote 5 We collected lists of registered lobbyists published by state officials, found in collections of lobbyist lists (i.e., Marquis Academic Media 1975; Reitman and Bettelheim Reference Reitman and Bettelheim1973; Wilson Reference Wilson1990), provided by the National Institute on Money in State Politics, or located in historical newspapers from the states. Footnote 6 The lists include names of lobbyists and their clients. Most lists were collected from state archives or libraries and are original documents. The secondary sources are compilations of lists provided by state authorities and were consulted where needed. We collected lists of registered lobbyists from all states as available for years around 1949, 1959, 1973, 1989, and 2009. These were the years for which the most lists were available from archives, libraries, or other sources. Footnote 7 From the lists, we first generated a data set consisting of all registered lobbyists in the American states for each of the five waves of observations. The data set includes more than 100,000 lobbyist-state-year observations.

There are no historical surveys of state lobbyists that inquired about ethnic or racial identities, so we inferred lobbyists’ identities from their names. We turned to a method developed by Imai and Khanna (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) featured in the R package wru. Footnote 8 The method uses a Bayesian approach to infer the identities of lobbyists by examining both first and last names alongside geocoded voter registration records. For reference, the U.S. Census asks respondents about their ethnic and racial identities such that different names are associated with various identities more or less often across counties. Using the method developed by Imai and Khanna, we inferred the identities of lobbyists by examining how often people with shared surnames living within the capital counties of lobbyists’ home states claimed to belong to one of the groups listed by the Census. Footnote 9

We assert that the Imai and Khanna (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) method for identifying lobbyists’ ethnicities and races is sufficiently accurate for testing our hypotheses but nevertheless produces some error. By examining a subset of lobbyists for which we have reliable identity information, we show that the method correctly identifies the ethnicity or race of at least 80% of white, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian-American lobbyists. Nearly 2,000 lobbyists in our data set consist of former state legislators who were registered to lobby in 1989 or 2009. Using legislator biographies and other sources (not surveys), Klarner (Reference Klarner2021) identified the ethnic or racial backgrounds of these legislators: he assigned a single identity to each legislator. We assume that Klarner coded the identities of the former legislators in our sample accurately, and that these identities allow us to test the accuracy of Imai and Khanna’s (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) method. We have no reason to suspect that the former legislators’ surnames are systematically different from those of all the other lobbyists in our sample.

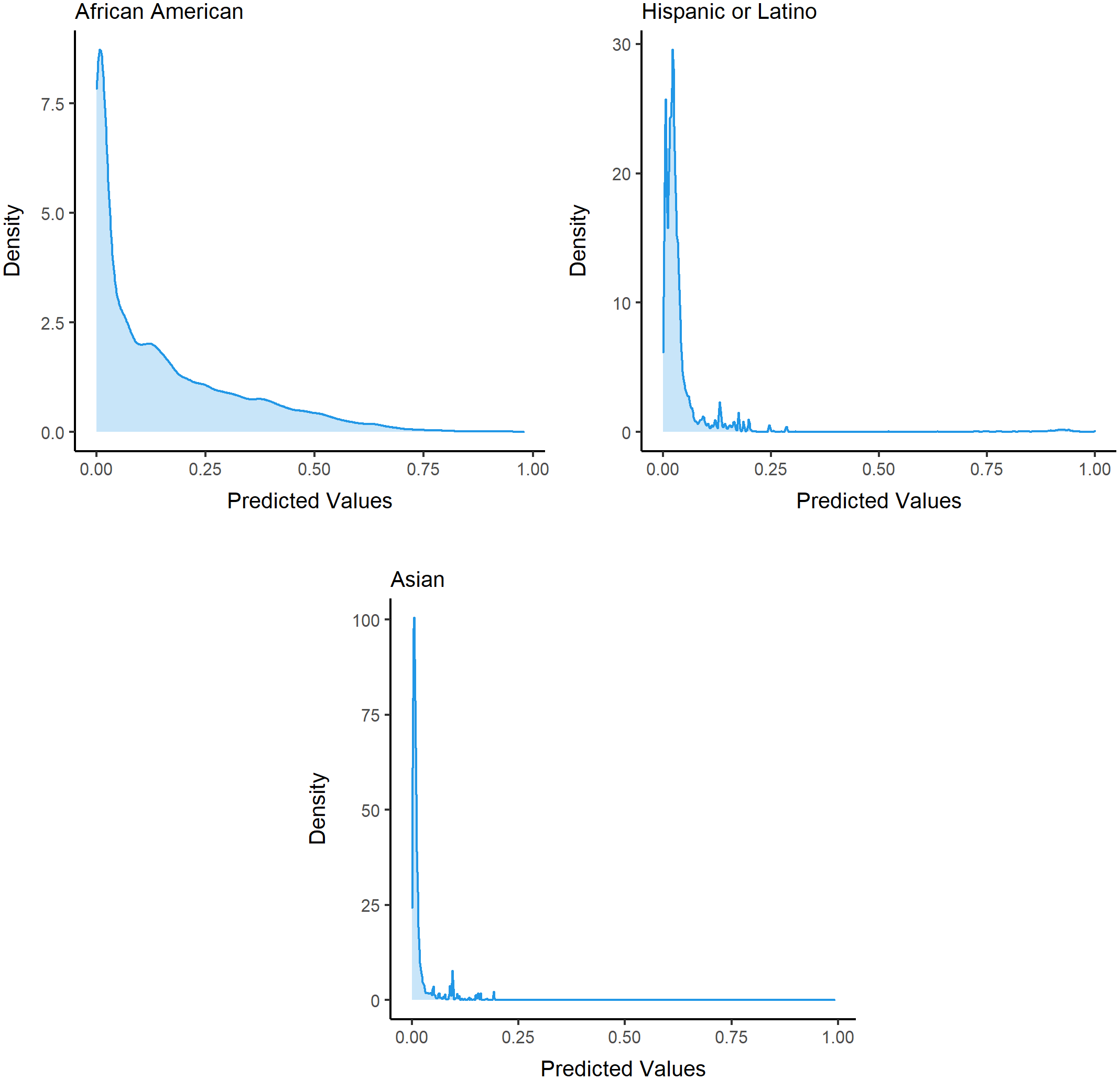

The accuracy of Imai and Khanna’s (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) identification method depends on chosen cut points. The method assigns to each lobbyist different probabilities of being a member of different ethnic or racial populations. For example, the method may state that one lobbyist has a 55% chance of being Hispanic or Latino and a 45% chance of being white, while another lobbyist may have a 100% chance of being Hispanic or Latino.

Figure 1 reports histograms for the ethnic or racial percentages of all lobbyists in our sample. The horizontal axes report the estimated percentages while the vertical axes report the numbers of lobbyists belonging within each percentage range. By turning to the nearly 2,000 former legislators in our data set, we calculated the percentage of those lobbyists whose identities were correctly determined at different cut points. These figures are presented in Fig. 2. At a 60% cut point, for example, more than 80% of lobbyists identified as Hispanic or Latino by the Imai and Khanna’s (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) method were correctly identified, according to Klarner (Reference Klarner2021). We provide additional information regarding numbers of false positives and false negatives for each cut point in the appendix. Throughout the study, we report ethnicity and race statistics for lobbyists who reportedly have a greater than 60% chance of belonging to any particular population. Footnote 10

Figure 1. Histograms of lobbyists’ predicted identities

Figure 2. Percentage correctly identified by group

Unfortunately, Imai and Khanna’s method is less reliable for identifying African-American lobbyists. From Fig. 2, the likelihoods of lobbyists being African American are more dispersed than the likelihoods of lobbyists being Hispanic or Latino or Asian American. This is due to increased frequency of shared surnames and given names between African-American and white lobbyists. For our statistical tests, however, the results remain valid provided that two conditions hold true. First, the lobbyists whom the method identifies as ostensibly African American must be more likely actually to be black than those whom the method does not identify as black. Second, lobbyists who are not black in reality but whom the method labels as black (i.e., false positives) must not be statistically different, in terms of clientele sizes or other traits, from the nonblack lobbyists who were correctly identified as nonblack (i.e., true positives). If these conditions hold true, then the inaccuracy of the Imai and Khanna method merely decreases the likelihood that we detect any effects of legislative diversification on the clienteles of African-American lobbyists. We show in the appendix that the conditions do indeed hold true.

While our lobbyist lists and method allow us to measure the ethnic and racial diversity of American state lobbyists, we need more information to understand better if inclusivity has increased. Using the lists, we calculated the total number of clients each lobbyist represented. This number helps provide insight into how much business nonwhite lobbyists attracted versus white lobbyists. Using methods developed by Strickland (Reference Strickland2020) and Strickland and Stauffer (Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022), we also identify former legislators and women who were registered lobbyists in our data set.

Diversity of State Lobbyists

Before testing our hypotheses, we present descriptive information regarding the diversity of state lobbyists. Table 1 presents total numbers of lobbyists and lobby contracts registered in the states where we retrieved registration rosters. Footnote 11 The table also reports how many lobbyists and contracts were predicted to belong to any ethnic or racial group at a 60% or greater chance per Imai and Khanna’s (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) method. We interpret these figures to be conservative estimates given that our identification method produces some error. The statistics presented show generally that state lobbyists are characteristically homogeneous both historically and in the present time, but that some diversification has occurred. The total number of lobbyists increased by more than 159% between the early 1970s and late 2000s (periods from when we have lobbyists rosters from nearly all states), but numbers of nonwhite lobbyists increased more sharply, especially numbers of Asian-American lobbyists. Similar trends are observed for numbers of lobby contracts represented by various lobbyists, but African-American lobbyists appear to have lost ground in comparison to other lobbyists over the same time since their relative change is lowest. Contract gains were particularly pronounced for Hispanic or Latino and Asian-American lobbyists, whose total client bases increased in size by factors greater than 22 and 31, respectively.

Table 1. Ethnicity and race in state lobbying over time

To get a better sense of whether diversification and inclusivity occurred concurrently, we compare the percentages of lobbyists who are nonwhite to the percentages of contracts (clients) those lobbyists represented. Figure 3 reports these percentages for all periods examined. In accordance with Table 1, the figure shows that African-American lobbyists generally lost ground between the 1970s and 2000s in terms of clients represented. Roughly 2.3% of all state lobbyists were black in both 1989 and 2009, but their share of contracts declined from about 2% to 1.78%. These numbers suggest that communities of state lobbyists became more diverse in terms of, but less inclusive for, African-American advocates over time. For Hispanics and Latinos, diversity and inclusion improved since the late 1980s. The average clientele size of these lobbyists reached parity with that of all other lobbyists by 2009. Asian-American lobbyists lost slight ground over time in terms of contract share.

Figure 3. Diversity and inclusion of state lobbying

Hypothesis Testing

We now turn to conducting statistical analyses to test our hypotheses or find evidence of our legislature-based narrative. Based on the dependent variable for each hypothesis, we use either state- or lobbyist-level data for tests. To allow for straightforward interpretation and comparison of effect sizes, we use least-squares regression analyses to test all hypotheses.

Using state-level data, we first examine whether the election of nonwhite legislators led to or was correlated with nonwhite identity group mobilization. In these regressions, the outcome variable is the number of lobby contracts tied to identity interest groups. These organizations include any client with an ethnic or racial identity included in its name. Examples include not only the NAACP and Mexican-American Legal Defense and Educational Fund but also business and occupational groups such as the Hispanic Chambers of Commerce and National Association of Black Social Workers. Importantly, we examine total lobbyists hired by such groups instead of counts of the identity groups themselves given that lobbyist counts better reflect degrees of mobilization among interests. Hypothetically, even though the NAACP may be the only identity-based interest active within a state over time, the number of lobbyists it hires may change drastically depending on whether it seeks to ramp up or tone down its lobbying efforts.

In our regression models, coethnic or coracial legislators (as measured by Klarner Reference Klarner2021) and state residents (in millions), overall policy liberalism (as measured by Caughey and Warshaw (Reference Caughey and Warshaw2017), and total lobby contracts (in thousands) all serve as predictor variables. Footnote 12 Our models also include fixed effects for states and observation waves, but those coefficients are not reported. This forces our models to estimate effect sizes based only on temporal changes that occurred within states (Mummolo and Peterson Reference Mummolo and Peterson2018).

From Table 2, we find limited support for our first hypothesis. The election of African-American legislators was correlated with the lobby contracts of African-American identity groups. For every additional black person elected to a state legislature between 1973 and 2009, black interests in the state collectively hired roughly 0.07 additional lobbyists on average, holding all other variables constant. In our sample, the median state had zero contracts representing black interests, and changes in numbers of African-American legislators ranged in value from 0 to 49 lawmakers. Based on the estimated effect size, the addition of 49 lawmakers would lead to three or four lobbyists representing explicitly black interests. We do not detect similar patterns for Hispanics or Latinos and Asian Americans. Interestingly, numbers of lobbyists representing black causes declined in states where black populations increased. One possible explanation for this trend is that, in states with growing black electoral power, black identity interests may have relied less on insider lobbying and more on outsider tactics like protests, letter-writing, and advertisements (as in Kollman Reference Kollman1998). For none of the groups were changes in policy liberalism correlated with changes in lobbying. Footnote 13 Unsurprisingly, changes in total contracts were correlated positively with changes in identity group contracts. Footnote 14

Table 2. Lobby contracts by nonwhite identity interests (state data)

No tes: standard errors in parentheses. State and period effects included in all models but not reported.

*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01 on two-tailed tests.

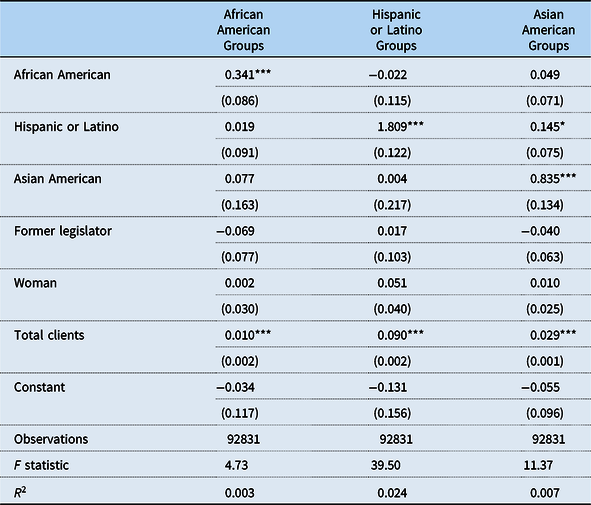

To test our second hypothesis, given that we are interested in detecting whether identity-based groups hired lobbyists who shared the identities of their members, we examine lobbyist-level data. In these tests, each observation is a single lobbyist and the outcome of interest is the number of nonwhite identity groups each lobbyist represented. As before, these groups consist of those with identities mentioned explicitly in their names, including both advocacy groups and occupational associations. The predictor variables include indicators for whether a lobbyist had a 60% chance or greater of being African American, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian American, an indicator for the lobbyists’ revolver status (i.e., whether or not he was a former legislator), an indicator for whether the lobbyist had a feminine given name, and a measure of how many contracts or clients the lobbyist represented overall. The first three indicator variables test our second hypothesis by comparing how often lobbyists with different backgrounds represented coethnic or coracial identity groups, in comparison to the reference category: white and all other lobbyists. Comparing the results for the indicator variables also allow us to determine if there was any cross-representation between groups.

The results presented in Table 3 demonstrate clear support for our second hypothesis: groups hired lobbyists who shared the ethnic or racial identities of their members. African-American, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian-American lobbyists each represented more coethnic identity-based interests than all other (primarily white) lobbyists, the omitted reference category. This effect was particularly pronounced for Hispanic or Latino lobbyists, who represented about 1.81 additional coethnic interests than all other lobbyists on average, with other variables held constant. Interestingly, there was little or no cross-representation between groups. From the model predicting representation of African-American groups, for example, Hispanics or Latinos and Asian-American lobbyists were no more or less likely to represent black groups than were white lobbyists. These trends were detected while we controlled for the effects of lobbyists’ revolver statuses, womanhood, and clientele sizes. Unsurprisingly, lobbyists with larger clienteles represented more identity interests. Footnote 15

Table 3. Representatives of nonwhite interests (lobbyist data)

Note s: standard errors in parentheses. State and period effects included in all models but not reported.

*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01 on two-tailed tests.

Thus far, we have found that the election of African Americans to state legislatures helped to diversify communities of state lobbyists by encouraging African-American identity interests to hire more lobbyists. While other identity groups hired representatives who shared their members’ identities, the election of coethnic or coracial legislators does not explain historical mobilization for those groups. In testing our final hypothesis, we examine the effects of legislative diversity on the inclusivity of communities of state lobbyists.

We proposed that interest groups hired coethnic or coracial lobbyists in response to the election of nonwhite legislators. We return to using state-level data since our primary independent variable of interest may be measured only at the level of states, and since numbers of lobbyists vary drastically across states such that any lobbyist-level analysis would reflect trends from some states more than trends from others. Across three models, our dependent variables are the numbers of lobby contracts represented, respectively, by African-American, Hispanic or Latino, or Asian-American lobbyists within each state and year. We control for numbers of coethnic or coracial legislators, revolvers, and residents, the liberalism of each state’s electorate (from Berry et al. Reference Berry, Ringquist, Fording and Hanson1998; Reference Berry, Ringquist, Fording and Hanson2010), and numbers of total lobby contracts within each state. The regression results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Lobby contracts by nonwhite lobbyists (state data)

No tes: standard errors in parentheses. State and period effects included in all models but not reported.

*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01 on two-tailed tests.

There is mixed support for our third hypothesis: only lobby contracts among Asian-American lobbyists increased in tandem with the election of coethnic legislators. For every additional legislator elected, Asian-American lobbyists (as an entire group within each state) gained seven additional contracts. The presence of coethnic revolving-door lobbyists overshadowed any effect of legislative diversity on the clienteles of African-American and Hispanic or Latino lobbyists. For every additional revolving-door lobbyist who was identified with these groups, all lobbyists in both groups represented more than 30 additional contracts on average and holding other variables constant. These results change, however, if we use different cut points for determining lobbyists’ ethnicities or races. We show in the appendix that African-American lobbyists did come to represent more clients as more black people were elected to state legislatures if we use 50% and 70% cut points for identifying black lobbyists. If we maintain the 60% cut point but remove revolver totals from the models, then contracts for lobbyists in all three groups appear to have increased in response to the election of coethnic or coracial legislators. This suggests that the mechanism linking legislative diversity with inclusivity among state lobbyists is driven primarily by the revolving door: as nonwhite people are elected to state legislatures, they eventually retire and may lobby. All the remaining results are generally unsurprisingly with one exception: in states where voters became more liberal over time, African-American lobbyists lost contracts. Footnote 16 This may be due to increased opportunities for outside lobbying but we do not know why the effects of this variable differ for lobbyists of different ethnic or racial identities.

Tenure and Partisanship Effects

Trends in legislator tenure and partisanship may have moderated or enhanced the relationship between numbers of nonwhite legislators and the hiring of nonwhite lobbyists. With regard to tenure, legislators gain institutional and policy knowledge and, occasionally, leadership positions by serving in office for longer periods of time (Carey, Niemi, and Powell Reference Carey, Niemi and Powell1998). If nonwhite legislators served for longer periods of time on average and acquired valuable leadership positions, then interest groups may have been even more likely to hire coethnic or coracial lobbyists to solicit those legislators. With regard to partisanship, nonwhite legislators may have more often been members of the Democratic political party than white legislators and, as a result, interest groups might have also been more likely to hire nonwhite lobbyists when Democrats controlled state legislatures (Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022). As of 2021, 13% of black state legislators and 13% of Hispanic or Latino legislators were Republicans (Smith Reference Smith2021a; Reference Smith2021b).

In models presented in the online supplemental material, we estimated the interactive effects of legislator tenure, partisan control, and the election of nonwhite legislators on the hiring of nonwhite lobbyists. In particular, we modified the specification of the regressions estimated for Table 4 by adding variables for tenure or partisan control, and interactive variables with totals of nonwhite legislators. To determine if tenure affected the link between the emergence of nonwhite legislators and the hiring of lobbyists, we incorporated measures of average years of experience for black, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian-American legislators into our models and produced interactive variables for tenure and total numbers of nonwhite legislators in each category. Tenure data were derived from Klarners’ (Reference Klarner2021) data set of legislators’ ethnic and racial identities. With regard to partisanship, we included in our models a Ranney (Reference Ranney, Jacob and Vines1976) index of the Democratic control of each state legislature for the preceding 6 years and also included an interactive variable with total legislators from each identity group. The index ranges in value from 0 for consistent Republican control to 1 for consistent Democratic control (Grossmann, Jordan, and McCrain Reference Grossmann, Jordan and McCrain2021).

Our results are informative. With regard to tenure, we found that average tenure among different nonwhite legislators did not affect the link between their totals and the hiring of coethnic or coracial lobbyists, except for Asian Americans. As more Asian Americans were elected to state legislatures, and as incumbents gained experience, interest groups hired coracial lobbyists more often (β = 0.81; p = .00). With regard to partisanship, we found that African-American lobbyists were no more or less likely to gain clients in response to the election of coracial legislators in more consistently Democratic legislatures (even when we excluded southern states), but that Hispanic or Latino lobbyists did gain more clients in response to the election of coethnic legislators in more consistently Democratic legislatures (β = 4.72; p = .01). Interestingly, this interactive effect was reversed for Asian-American lobbyists such that they gained fewer clients in response to the election of coracial legislators in more Democratic assemblies relative to similar lobbyists in more Republican assemblies (β = −2.12; p = .00). One possible reason for this finding may be that some Asian-American legislators gained leadership positions (that attracted lobbyists) in Republican assemblies. These results are presented in the online appendix.

Implications and Future Directions

For decades, political scientists and others knew little about the ethnic and racial composition of American lobbyists. While surveys of lobbyists were administered inconsistently, a consistent result emerged: lobbyists were generally less diverse than the American population. While the political mobilization of ethnic or racial identity interests received scholarly attention, little was said about the identities of lobbyists. As a result, it was unknown if nonwhite lobbyists truly were gaining ground, and what factors might explain the diversity and inclusivity of communities of lobbyists.

In this study, we proposed that the election of nonwhite legislators contributed to the historical diversification and inclusivity of communities of state lobbyists, particularly by mobilizing identity-based interests and encouraging non-identity-based interests to hire nonwhite advocates. We tested three hypotheses to find evidence for our narrative. We found somewhat supportive evidence. Legislative diversity likely led to more African Americans lobbying since it was correlated with coracial identity interests hiring more lobbyists, and since all categories of nonwhite identity interests hired advocates who shared the identities of members. Legislative diversity likely improved the inclusivity of communities of lobbyists for Asian Americans since those lobbyists gained clients (relative to others) as more Asian Americans were elected to office. Demographic trends, as well as shifts in numbers of revolving-door lobbyists, best explain the client counts of Hispanic or Latino lobbyists, although these lobbyists did gain clients in response to the election of coethnic legislators in more consistently Democratic legislatures.

Our findings have implications for employment opportunities and representation. Lobbyists registered in the states continue to reflect poorly the ethnic and racial diversity of the American population. The election of nonwhite legislators might have improved how well organized interests and lobbyists represented ethnic and racial interests but, at an aggregated level, inclusivity (in terms of client shares) did not follow diversification for African- and Asian-American lobbyists. Skrentny (Reference Skrentny2014) provides some possible insight into such slow change. He argues that contemporary firms in the USA have come to rely on “racial realism” when making employment decisions: potential employees may be valued for how well they reflect the customer or client bases of organizations, but employers must also adapt to the requirements of anti-discrimination laws crafted during times of overt discrimination. While the lobby value of different potential employees might change as legislatures become more diverse, non-identity-based organizations may be slow to diversify their lobby staff due to long-standing anti-discrimination laws or expertise accrued by current employees. Nevertheless, members of the CBC remain concerned over the slow pace of equitable employment within Washington’s lobby firms (Fuchs and Barròn-Lòpez Reference Fuchs and Barròn-Lòpez2021).

Our most intuitive finding also has implications for employment opportunities and representation. We found that ethnic and racial identity groups consistently hired lobbyists who reflected the identities of their members, and that there was little cross-representation among African-American, Hispanic or Latino, and Asian-American causes and advocates. Yet, the Congressional Black, Hispanic, and Asian American Pacific Caucuses formally agreed to work together on issues of mutual concern in 2005 so as not to compete for limited federal resources. The resulting Congressional Tri-Caucus was the “first deliberately cross-cultural alliance designed for the specific purpose of exchanging ideas and promoting a solid voting bloc” (Tyson Reference Tyson2016, 1). If interest groups in Congress are similarly segmented by identity as those in the states, then members of the Congressional Tri-Caucus may need to balance intergroup conflict among lobbyists with caucus goals that transcend group boundaries (Hero and Preuhs Reference Hero and Preuhs2013). Since organized interests often are supported by individual voters or donors who are prone to intergroup conflict, perceptions of linked political fate may be insufficient for them to hire individuals from beyond their membership bases.

We encourage others to consider and examine more carefully why trends in African-American mobilization and lobbying may be different from those of other ethnic or racial groups. From our findings, although Imai and Khanna’s (Reference Imai and Khanna2016) method identified black lobbyists less accurately than lobbyists from other groups, state-level trends among black interests and lobbyists most closely matched our expectations regarding historical change. It may be the case that African Americans generally have a stronger group consciousness than other nonwhite groups and that, as a result, the election of African Americans to state legislatures encouraged coracial group mobilization to a greater extent (Dawson Reference Dawson1994; Sanchez and Vargas Reference Sanchez and Vargas2016). It may also be the case that African-American voters were more concentrated in specific legislative districts than voters from other backgrounds such that descriptive representative in legislatures more naturally led to the mobilization of groups seeking to subsidize allied efforts (as in Hall and Deardorff Reference Hall and Deardorff2006).

Our results suggest new avenues for research. While we controlled for totals of revolving-door lobbyists, it remains unknown why some groups of legislators are more or less likely to become lobbyists than others. African- and Asian-American lobbyists may have attracted fewer clients than Hispanic or Latino lobbyists (from Fig. 3) due to differences in their propensities to become lobbyists. Yet, revolving-door lobbyists often have the most clients and attract the most valuable contracts in both Congress and the state legislatures (LaPira and Thomas Reference LaPira and Thomas2017; Strickland Reference Stricklandin press). Also, the method we used to infer the identities of lobbyists may be applied to political systems beyond the American states. It would be instructive to see whether or how communities of lobbyists in Washington and other national capitals diversified over time, although similar census classifications for ethnicity or race would be needed. Trends for Congress may differ from the trends we found in state legislatures. In the second half of the twentieth century, the Congress was active in enacting landmark civil-rights laws. It may be the case that related mobilization permanently improved the diversity of lobbyists in Congress (Grossmann Reference Grossmann2012).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2023.12

Acknowledgments

The authors thank participants of the 2022 Kopf Conference at Arizona State University titled “Puentes: Bridging American Politics’ Interest Group and Institutions Research” for their constructive comments. Participants included Jason Casellas, Nhat-Dang Do, Matt Grossman, Rodney Hero, Eric Juenke, Thad Kousser, Ben Marquez, Mark Ramirez, Michael Minta, Robert Preuhs, Stella Rouse, Lisa Sanchez, and Anne Whitesell. The authors thank Joshua Basseches, Janet Box-Steffensmeier, Tom Holyoke, and Huchen Liu for comments provided at other conferences. The authors thank three anonymous reviewers for their constructive guidance.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.