Introduction

Wari (AD 600–1000) was the largest pre-Inca civilisation in the Andes. Despite years of research on Wari, debate continues concerning its political organisation, degree of power and relationship to other societies. The central disagreement concerns whether Wari was an empire (Lumbreras Reference Lumbreras1974; Isbell & McEwan Reference Isbell and McEwan1991; Schreiber Reference Schreiber1992; Williams & Isla Reference Williams and Isla2002) or an interregional interaction sphere (Shady Solís Reference Shady Solís1988; Topic & Topic Reference Topic, Topic, Kaulicke and Isbell2000; Jennings Reference Jennings2006; Owen Reference Owen and Jennings2010). We argue here that, while Wari greatly facilitated and increased interregional interaction and trade, it was an empire, and that its control of coastal areas has been underestimated. Long proposed to have been governed by Wari (Menzel Reference Menzel1964), coastal Nasca contains Wari sites and artefacts, but doubts remain about Wari's role in the region.

Here, we report the results of new excavations at Huaca del Loro in Nasca. Three hypotheses are investigated: was the site a Wari colony, a local settlement interacting with Wari, or a place established to resist Wari control? Our research is part of the resurgence of imperial studies that prioritises bottom-up, agent-oriented perspectives, and questions a uniform view of empires (see Boozer et al. Reference Boozer, Düring and Parker2020). The relationship between Wari and Nasca is key to understanding broader processes that took place in other ancient empires, including the formation and expansion of first-generation empires, strategies and negotiations used by both empires and the communities that they attempted to dominate, and the transformation and resilience of local societies in colonisation contexts.

Wari and Nasca

Wari developed out of the Huarpa Culture of the Early Intermediate period (AD 1–600) in the Ayacucho region of the Central Highlands of Peru (Figure 1) (Leoni Reference Leoni2009). By the Middle Horizon (AD 600–1000), the capital city of Wari covered almost 15km2, with an estimated population of 40 000 (Isbell Reference Isbell, Evans and Pillsbury2004a: 203). The city contained distinctive architecture, including large orthogonal, rectilinear compounds with central patios, D-shaped temples and elaborate tombs. To support its large population, agricultural production intensified over time through terracing and irrigation systems (Ochatoma Paravicino & Cabrera Romero Reference Ochatoma Paravicino and Romero2001). By the mid eighth century the Wari-controlled area had expanded into much of highland Peru and parts of the coasts, covering up to 320 000km2 (Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Bergh2012: 39). In many areas, Wari built distinct settlements that served as seats of regional political power, economic and trade centres, storage facilities, and ritual and feasting locations (Schreiber Reference Schreiber1992; McEwan Reference McEwan2005; Nash Reference Nash and Bergh2012). Roads, including one through Nasca, connected major sites and resources (Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Kendall1984: 89). Pottery, textiles, obsidian, Spondylus shell and new metals made from copper alloys (e.g. Pillsbury Reference Pillsbury1996; Burger et al. Reference Burger, Mohr-Chávez and Chávez2000; Lechtman Reference Lechtman and van Zelst2003) circulated through Wari trade networks. Yet, despite evidence that Wari was an expansive civilisation, there remains a reluctance to call it an empire.

Figure 1. Map of Nasca drainage, with sites mentioned in the text and inset showing the capital city of Wari (figure by C.A. Conlee).

Ayacucho-Nasca connections extend back to the Huarpa Culture, which adopted aspects of Nasca iconography and ceramic technology (Menzel Reference Menzel1964; Benavides Calle Reference Benavides Calle1971; Knobloch Reference Knobloch1983; Proulx Reference Proulx2006). At the end of the Early Intermediate period, a time of increasing aridity on the desert coast, some Nasca people (including artisans) possibly moved into the highlands, where conditions were more favourable (Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Stein2005: 247; Eitel & Mächtle Reference Eitel, Mächtle, Reindel and Wagner2009: 27). Indeed, mitochondrial DNA data support such a migration into the highlands c. AD 640 (Fehren-Schmitz et al. Reference Fehren-Schmitz2014). Pottery styles flowed both ways, as evidenced by the inclusion of Wari-style elements in local Middle Horizon Nasca pottery (called Loro after the type-site Huaca del Loro). Also important to Wari expansion was religion, which included ancestor worship and rituals involving trophy heads (Cook Reference Cook, Benson and Cook2001; Ochatoma Paravicino & Cabrera Romero Reference Ochatoma Paravicino, Romero, Silverman and Isbell2002; Tung Reference Tung2012). The trophy heads were possibly popularised through Nasca influence, as the practice was widespread on the south coast before the Middle Horizon, although they were made and used differently in the two regions (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Forgey and Klarich2001; Kellner Reference Kellner and Bonogofsky2006; Conlee et al. Reference Conlee2009; Knudson et al. Reference Knudson2009; Tung Reference Tung2012).

Wari presence in Nasca is evidenced by the colonies, new mortuary practices, changes in local settlements, Wari pottery and other highland imports. Over 40 Wari-affiliated sites have been identified in the cabezadas (relatively gently sloping terrains in steep valley locations) zone between 2000 and 4000m asl, including Huayuncalla and Incawasi (Figure 1; Edwards & Schreiber Reference Edwards and Schreiber2014; Isla Cuadrado & Reindel Reference Isla Cuadrado and Reindel2014; Sossna Reference Sossna2014). These settlements contain rectangular compounds and Wari pottery, and one (Pacapacarí) has two D-shaped temples. None has defensive walls or any evidence for conflict (Sossna Reference Sossna2014: 196). In the lower valley, the site of Pacheco was an important ritual location, and probable colony, yielding oversized, highly decorated pots that were deliberately broken and deposited—similar to those found at Conchopata near the Wari capital (Menzel Reference Menzel1964; Tello Reference Tello2002; Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Stein2005). Pataraya, situated between Pacheco and the cabezadas, was a small Wari site near an ancient road linking the coast to the highlands, probably established to facilitate and control trade (Edwards & Schreiber Reference Edwards and Schreiber2014). Located at a similar elevation, Lambrasniyoq has rectilinear compounds and a D-shaped temple (Isla Cuadrado & Reindel Reference Isla Cuadrado and Reindel2014).

Loro pottery is the most prevalent type at both Wari and local Nasca sites. Loro (previously called Nasca 8; Menzel Reference Menzel1964) is connected stylistically to Late Nasca pottery (Nasca 7) and to that from Ayacucho (Knobloch Reference Knobloch1983; Silverman Reference Silverman1988). Loro was thought to date to the first two phases of the Middle Horizon, although it is documented at sites in Nasca that range from AD 550–920 and is often associated with Nasca 7 pottery and/or the Chakipampa and Viñaque Wari styles (Menzel Reference Menzel1964; Unkel et al. Reference Unkel2012; Sossna Reference Sossna2014; Conlee Reference Conlee2016; Edwards Reference Edwards, Rosenfeld and Bautista2017; Kerchusky Reference Kerchusky2018). Evidence of highland connections include the presence of greater quantities of obsidian from the Quispisisa source that was probably under Wari control, as well as highland-style textiles and objects of copper alloys, including bronze tupu pins (Isla Cuadrado Reference Isla Cuadrado, Reindel and Wagner2009; Conlee Reference Conlee2016).

Wari-style mausoleums containing multiple burials and high-status grave goods are common at both local and Wari settlements in Nasca. These replaced the individual interments of the previous period (Ochatoma Paravicino & Cabrera Romero Reference Ochatoma Paravicino and Romero2001; Isbell & Cook Reference Isbell, Cook, Silverman and Isbell2002; Isbell Reference Isbell2004b; Isla Cuadrado Reference Isla Cuadrado, Reindel and Wagner2009; Conlee Reference Conlee2011). Oxygen and strontium isotopic analyses have identified two non-local individuals buried in the mausoleums at La Tiza. Both are women in their early twenties, who may have married into the community to create ties between local elites and Wari (Conlee et al. Reference Conlee2009; Buzon et al. Reference Buzon, Conlee, Simonetti and Bowen2012). Preliminary strontium analysis of individuals from the Pataraya tombs indicates that some of the population may have come from the Wari heartland. Increased variation in cranial vault modification styles, including annular styles, also indicates migration (Kellner Reference Kellner2002; Buzon et al. Reference Buzon, Conlee, Simonetti and Bowen2012). Close to Wari settlements, diet shifted towards maize, but in the far southern Las Trancas Valley, the average diet remained unchanged. Even so, a small subsection of the population consumed less meat and more potatoes and beans, suggesting a strain on maize agriculture (Kellner & Schoeninger Reference Kellner and Schoeninger2008). Disease increased slightly and those buried with Wari ceramics exhibit more trauma (Kellner Reference Kellner2002). In sum, Nasca archaeological evidence indicates a close relationship with Wari dating back to the Early Intermediate period Huarpa Culture. In the Middle Horizon several Wari colonies were established, the import of highland goods increased and non-local individuals were present.

Huaca del Loro

Huaca del Loro plays a central role in interpretations of the Middle Horizon in Nasca. Spanning at least 20ha, the site is located in the Las Trancas Valley—the southernmost valley of the Nasca drainage—at 600m asl. Sand covers many of the architectural remains and protects parts of the settlement. At least eight functioning puquios (horizontal wells) were operational in the valley during the Middle Horizon (Schreiber & Lancho Rojas Reference Schreiber and Rojas2003: 115), making it a productive agricultural area. Five kilometres east is Zorropata, a 3ha site occupied in the late Early Intermediate period and the early Middle Horizon (AD 416–765), with ceremonial, burial and domestic areas (Kerchusky Reference Kerchusky2018). Seven trophy heads in the local Nasca style were recovered at Zorropata; they are mostly of non-local origin, in contrast with other trophy heads found in the region. Concentrations of slingstones and a system of walls along the western and southern areas indicate the importance of defence.

Previous research

Huaca del Loro was first identified by a team led by Julio C. Tello in 1927, and was named Tambo de Kopara (Tello Reference Tello2002: 94–95). Toribio Mejía, who conducted most of the fieldwork, created four field maps and identified three areas (Figure 2). Area A, in the south-west of the site, contained a circular structure and large rectangular compounds, described as the neighbourhood of the principal ayllu (kin group). To the north, area B was defined as the cemetery of the principal ayllu, and five tombs (two intact and three looted) were excavated (Tello Reference Tello2002: 14–24). These large, square tombs were constructed of adobe and stone in the high-status Nasca barbacoa style (i.e. roofed with wooden beams). Area C, in the east, had no visible architecture and is interpreted as the neighbourhood of the common people, or secondary ayllu. None of the structures recorded on the maps is intact or visible today, except for the round temple and some of the walls of the looted tombs.

Figure 2. Map combining Mejía's four field maps (Tello Reference Tello2002: 16, 18 & 94–95) (figure by E.A. Carmichael).

A team led by William Duncan Strong (Reference Strong1957) conducted excavations during an expedition in 1952–1953 (Figure 3). Strong renamed the site Huaca del Loro, and defined the Loro ceramic style. Strong's team focused on excavating the round temple, which was built of stone, with a plastered floor and red-painted walls (Strong Reference Strong1957: 36). Several rooms with thick walls adjoined the temple and contained items such as mummified macaws, fossil whale bones, llama and guinea pig remains and unworked stone monoliths, all of which were interpreted as sacrificial materials. Immediately to the north and east, two large compounds, now destroyed, contained a series of rooms. Strong excavated one compound room (room 1) to the north of the temple and a unit in a nearby midden to the west (cut 1)—the latter now entirely destroyed by modern activity. In the cemetery area north of the compounds, looted, deep rectangular tombs made of semi-cylindrical adobe bricks were recorded, some with painted walls. Strong (Reference Strong1957: tab. 4) obtained two radiocarbon dates of AD 755±80 and 985±70 (uncorrected) from the temple area.

Figure 3. Strong's map of Huaca del Loro (Reference Strong1957: fig. 16) (map redrawn by E.A. Carmichael).

Paulsen (Reference Paulsen and Sandweiss1983) re-analysed Strong's work, and argued that Huaca del Loro was a highland colony, as circular, stone buildings are characteristic of the highlands rather than the coast. She proposed that the temple represented Huarpa expansion (Paulsen Reference Paulsen and Sandweiss1983: 104). The round temple has similarities to a late Huarpa ceremonial building at Ñawinpukyo in the Wari heartland (Leoni Reference Leoni2009: fig. 2) and to a large, circular funerary structure with a central square chamber at Huayuncalla (Sossna Reference Sossna2014: 47). Cook (Reference Cook and Bray2015) proposes that circular structures amid rectilinear architecture represent a Huarpa tradition that led to Wari D-shaped temples. It has further been suggested that Huaca del Loro was an early Wari provincial centre with occupation dating back to Huarpa (Paulsen Reference Paulsen and Sandweiss1983; Isbell Reference Isbell and Manzanilla1997).

Schreiber (Reference Schreiber1989) recorded Huaca del Loro during a regional survey in the mid 1980s. She estimated that the site covered 15–20ha, noting that only a small fraction had been investigated. Schreiber (Reference Schreiber1989: fig. 3) reported that an area north-east of the temple had been bulldozed sometime before 1984, and that looting had increased since Strong's investigations. On a regional scale, she found that Middle Horizon settlement was densest in Las Trancas and that Huaca del Loro was the largest site, proposing that it was the centre of a small polity established to escape and resist Wari control (Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Stein2005).

Current research

Huaca del Loro figures prominently in discussions of Wari expansion in Nasca and the impact on local people. To explore these processes, the current project tests three hypotheses: that Huaca del Loro was 1) a local Nasca settlement; 2) a Wari colony; or 3) a site of resistance. If it was a local settlement, then established practices and material culture would predominate, along with some hybrid Wari/Nasca material. If a Wari colony, we would expect to find imperial architecture (e.g. rectilinear compounds, D-shaped temples, mausoleums), Wari artefacts (e.g. ceramics, textiles, bronze), and large quantities of goods exchanged over long distances (e.g. obsidian, Spondylus shell). If a site of resistance, we would anticipate local architecture and goods, a rejection of Wari practices and evidence of conflict and violence.

We defined five sectors through geophysical and surface surveys (Figure 4). Far to the west is sector I, where ground-penetrating radar (GPR) identified subsurface rectangular architecture. Sector II includes the round temple and compounds designated area A by Mejía and excavated by Strong. Sector III is the looted cemetery, with tombs investigated by Tello and Strong. In the central and eastern portion of the site, sectors IV (the western part was Mejía's area C) and V (not previously considered part of the site) contain no visible architectural remains but dense archaeological surface material. The division of sectors IV and V is arbitrary, as the two are not easily distinguishable by surface features or in the geophysical data. During 2019, we focused on sectors I, III and IV; stratigraphic excavations were conducted and material was sieved through a ¼ inch screen. Photogrammetry (Structure from Motion) was used to record contexts and to generate 3D models. Although samples were selected for radiocarbon-dating, results continue to be delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 4. Map of Huaca del Loro, with sectors, excavation units and inset of structures 1–2 (figure by N.W. Berry).

Excavation was concentrated in sector I, where GPR identified rectangular structures approximately 0.45–0.55m below the surface. Six trenches were dug to locate architectural remains and, once the walls were exposed, the trenches were extended to define the structures and rooms (Table 1). Structure 1 is a rectangular compound with six rooms exposed to date. The architecture is Wari in terms both of layout and construction. The rooms include a large patio, a room with a wooden post and stairway, a narrow gallery and a room containing circular features that may be storage pits or tombs. The walls are double-coursed and constructed of angular and shaped stone, adobe with mud mortar and remnants of white plaster. Floor areas are white and compact, and in various states of preservation. Future fieldwork will expose the rest of the compound and complete the excavation of the rooms.

Table 1. Areas excavated at Huaca del Loro during the 2019 field season.

GPR survey conducted around structure 1 identified a large, round building located immediately to the south. Excavation revealed a clear D-shaped temple (structure 2), 10m in diameter and with 1m-wide walls (Figure 5). The straight side runs north–south and features a 1m-wide doorway opening east. The walls are double-coursed and constructed of angular stones, with clay mortar and white plaster. Excavation, on average to a depth of 0.40m, did not reach the floor level and much of the interior remains to be excavated. It appears that the temple was deliberately filled in and raw cotton placed around the exterior (Figure 6). A bag, possibly containing the mineral limonite (used to make yellow pigment), was placed in a corner where the rectangular compound intersects the temple (K.J. Vaughn pers. comm.) (Figure 7). Ceramics found in the temple and compound were predominantly local Loro, with some Viñaque, Chakipampa and Nasca 7 types (Figure 8).

Figure 5. Compound (structure 1) and D-shaped temple (structure 2) (figure by B.E. Heisinger).

Figure 6. Cotton along exterior of the Huaca del Loro temple wall and raw cotton inset (figure by C.A. Conlee).

Figure 7. Bag containing limonite from the temple at Huaca del Loro (figure by C.A. Conlee).

Figure 8. a) Left: Viñaque pottery from the south extension; right: Chakipampa and Viñaque pottery from trench 1; b) fragment of Loro face-neck jar from the south-west extension, and Loro bowls from the south extension; c) Loro figurine from the south extension. Details of the contexts can be found in Table 1 and Figure 5 (figure by C.A. Conlee).

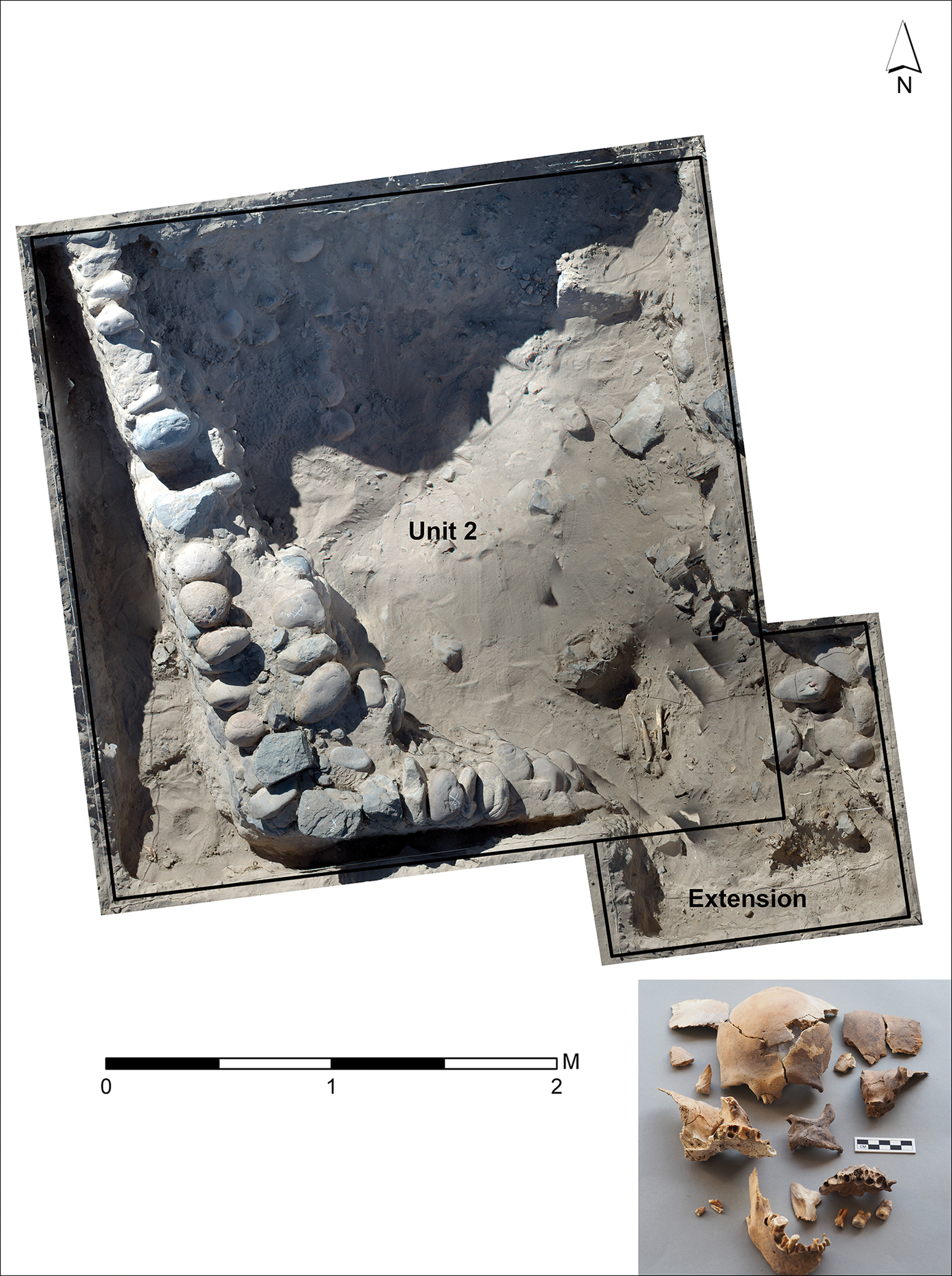

Four units were excavated in sector III. This extensively looted cemetery contains large adobe and stone walls, with square, chambered tombs. Although no intact burials were excavated, isolated human skeletal elements, in various states of preservation, in units 1, 2, 6 and 7 represent a total of seven adults and one juvenile. Unit 2 consisted of a looted tomb containing at least five adults, including one trophy head of a young adult male (Figure 9). With a ‘mask’ style, a frontal hole made at the glabella and no cranial vault modification, this example resembles Nasca rather than Wari trophy heads (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Forgey and Klarich2001; Kellner Reference Kellner and Bonogofsky2006; Tung Reference Tung2012). Other individuals exhibit the typical Nasca fronto-occipital cranial vault modification style. Local pottery, along with local-style cranial modification and ‘mask’ trophy head, suggests that the individuals buried in the mausoleum style—a practice introduced through Wari influence—were of local origin.

Figure 9. Unit 2 and trophy head at Huaca del Loro (image created with the help of B.E. Heisinger).

Three units and one profile were excavated in sector IV, which comprises a large area covered with sand and dense cultural material. Profile 1 and unit 4 yielded the remains of quincha walls made of tied cane and probably mud (i.e. wattle and daub) (Figure 10). Used extensively at Middle Horizon Zorropata to the east, quincha structures can be built quickly and are commonly found at local Nasca sites. Material excavated was consistent with domestic areas and contained local Loro ceramics. Overall, the excavations in this sector indicate the presence of local people using established construction techniques and pottery. The areas tested were, however, limited, and future excavations will explore whether this sector housed local people who worked for Wari, or whether it belongs to an earlier phase, the local people having left or being forced out when the Wari colony was established. Alternatively, this sector may contain yet undiscovered Wari architectural remains.

Figure 10. Unit 4 with quincha wall at Huaca del Loro (figure by B.E. Heisinger).

Wari colonialism in Nasca

The discovery of Wari architecture and artefacts suggests that Huaca del Loro was a colony and that Wari exercised control in a variety of regions, including Nasca and the coast. Several sites in Nasca are now known to feature Wari rectangular architecture, D-shaped structures, and/or imperial pottery and imported goods. Huaca del Loro is the lowest-lying site, one of only a few that contains all of the above characteristics, and the first such site to have been extensively excavated. D-shaped structures are not documented at all Wari sites. Even the immense highland centre of Pikillacta (McEwan Reference McEwan2005) lacks such structures, as does Pataraya (a road station occupied by a small community; Edwards & Schreiber Reference Edwards and Schreiber2014), the only other excavated Wari site in southern Nasca. What makes Huaca del Loro distinctive may be connected to the length or intensity of its occupation, as well as its function. Given that D-shaped structures are interpreted as temples, we can suppose that their construction indicates intensive ritual activity and the presence of religious officials. The placement of offerings of raw cotton around the exterior wall of the temple at Huaca del Loro, as well as its presence in many other contexts, suggests that this coastal product was a focus of Wari interest in the area. If this region was a centre of cotton production, then Huaca del Loro was probably an important economic hub that housed a variety of people. The fact that the site has a large area inhabited by local people constitutes another distinguishing trait. This population may have provided support personnel for the Wari installation, which would have required the presence of various types of administrators and managers, including Wari elites, served by a D-shaped temple.

The chronology of Huaca del Loro has yet to be fully established. Stylistically, the pottery and architecture suggest that it spans the late Early Intermediate period to at least the middle of the Middle Horizon (c. AD 550–800). The site appears to be part of an early Wari expansion into Nasca. Refinement of this chronology requires further excavation and modern radiocarbon-dating, which will influence future interpretations. While it appears that Huaca del Loro was not a site of resistance, as had been previously proposed (Schreiber Reference Schreiber and Stein2005), it is possible that people resisted and were defeated by Wari, who then set up a colony, if the extensive local area of the settlement was occupied before the imperial sector.

Wari was a first-generation (or primary) empire that developed from Indigenous roots, and its organisation and strategies probably differed from those of ‘shadow empires’, such as the Xiongnu of the Mongolian steppe (Barfield Reference Barfield, Alcock, D'Altory, Morrison and Sinopoli2001) that arose, in part, through contact with neighbouring polities, or of ‘successor empires’ that subsequently developed. The latter include the Inca, who built on Wari organisation and infrastructure (Düring et al. Reference Düring, Boozer, Parker, Boozer, Düring and Parker2020; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Nash, Chacaltana, Boozer, Düring and Parker2020). Wari's earliest colonies, such as those in Nasca, were probably located where the people of Ayacucho had long-established ties. Nasca was incorporated during a period of primary expansion, which, as seen in many empires (e.g. the Assyrian Empire), affects well-known regional corridors (Parker Reference Parker, Boozer, During and Parker2020). During primary expansion, empires often spread via existing communication and transport networks, along which are local centres that are taken over to control ‘pockets’ of territory and to protect goods and people in transit (Liverani Reference Liverani1984; Parker Reference Parker, Boozer, During and Parker2020). The relationship between Wari and Nasca was complex and strong, extending back to the period before imperial expansion. Nasca was incorporated early into the Wari Empire, probably for both economic and ideological reasons. The Nasca region supplied important coastal crops, such as cotton, and its influential religion involving trophy heads provided a powerful belief system and practices that Wari could have incorporated into its own.

First-generation empires such as Wari probably employed many strategies, even within a single province. Furthermore, they involved many diverse agents, as they were working without a blueprint, experimenting with different types of control and managing a variety of interests. Local people responded and interacted in a range of ways as they negotiated this new type of external power. Such diversity is evident in Nasca in the different types of settlements established by Wari, and in the variable relationships between Nasca and Wari peoples. The Huaca del Loro colony may have exerted considerable control over the local population, either by employing them or forcing their departure. Nearby Zorropata, without Wari presence and with defensive features, indicates possible warfare with Wari. By contrast, Wari sites farther north show few signs of conflict and include a major religious offering deposit at Pacheco and evidence of intermarriage. Variability of this type can obscure the powerful nature of Wari and may explain why some researchers reject the idea of it being an empire. It is certainly not a unique situation, as this kind of variability can be found in other first-generation empires, such as the Akkadian Empire (e.g. Foster Reference Foster2016; Schrakamp Reference Schrakamp and MacKenzie2016)—and such variability may be an important factor in the study of other emerging empires.

Acknowledgements

The Peruvian Ministry of Culture granted permission to conduct fieldwork.

Funding statement

The research at Huaca del Loro was funded by the National Science Foundation (grant BCS-1758084), a grant from the Curtiss T. Brennan and Mary G. Brennan Foundation, and the Research Enhancement Program at Texas State University.