Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), an acute respiratory disease, was first reported in December 2019 in Wuhan, China. The virus has spread internationally and, through late 2020, continues to have unprecedented impact on our health and ways of life. The closing of schools and businesses, extremely high unemployment rates, and the effect of quarantine are additional stressors due to public health measures in place to limit spread of COVID-19. There are significant psychological effects of the pandemicReference Wang, Pan and Wan1,Reference Brooks, Webster and Smith2 that affect the general population and may be more pronounced in certain groups (e.g. female, socially stressed, frontline worker, pre-existing psychological disorder; see Lai et alReference Lai, Ma and Wang3). Provision of support for these challenges are complicated by the high number of people requiring support and the need to maintain physical distancing.

Mobile health technology offers a unique and innovative solution in this context. Specifically, this tool offers a convenient, cost-effective, and accessible means for implementing population-level interventions. Smartphone ownership is prevalent in Canada, text-messaging is free to end-users, does not require technical skill for use, and does not require expensive data plans. Text messages are also cost-effective to providers, costing cents per message to deliver.Reference Agyapong, Mrklas and Juhás4 Use of supportive text messages has shown positive outcomes in randomized controlled trials, including reduction of depressive symptoms,Reference Agyapong, Ahern and McLoughlin5 increased abstinence duration in alcohol use disorder,Reference Agyapong, Ahern and McLoughlin5 and high user satisfaction evinced by previous research.Reference Agyapong, Milnes and McLoughlin6

This study describes effects of implementation of the Text4Hope program,Reference Agyapong7 a low-cost, evidence-based, supportive text messaging service free to all Canadians who wish to subscribe during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Baseline data collected at the start of messaging indicated that the majority of subscribers endorsed elevated levels of stress and depressive and anxiety symptoms.Reference Nwachukwu, Nkire and Shalaby8 The primary aim of the study was to assess whether the Text4Hope program would reduce stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms at the third-month follow-up. A randomized controlled trial of daily supportive text messaging resulted in close to a 25% additional improvement in Becks Depression Inventory scale-measured mood at the third-month follow-up assessment in the intervention group compared with the control group.Reference Agyapong, Ahern and McLoughlin5 Based on this, the study hypothesis was that the Text4Hope intervention would result in ≥25% reduction in mean scores and prevalence rates in all 3 factors: the Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10), General Anxiety Disorder Scale 7 (GAD-7), and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) scales at 3rd month versus baseline. This study is part of a larger project,Reference Agyapong, Hrabok and Vuong9 with additional results forthcoming. A literature search on major scientific data bases, including; MEDLINE, Scopus, Embase, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Chemical Abstracts, and PsychINFO, suggests that, this is the first study to report 3rd-month outcomes for a supportive text message program which seeks to address stress, anxiety, and depression at the population level during a pandemic.

Methods

Complete methods details, including sample size estimations and citations for standardized scales are provided in the published protocol.Reference Agyapong, Hrabok and Vuong9,Reference Agyapong, Hrabok and Vuong10 In summary, this cross-sectional study was approved by the Research and Ethics Board of the University of Alberta (Pro00086163). Participation was voluntary; individuals self-subscribed to receive daily supportive text messages for 3rd month by texting the word “COVID19HOPE” once to a specified number. This program was launched through an announcement by Alberta’s Chief Medical Officer of Health on behalf of Alberta Health Services and the Government of Alberta on March 23, 2020. The announcement was widely broadcast across many electronic and print media networks in Alberta to inform Albertans about the program.Reference Pearson11 Albertans were further made aware of the program by means of websites dedicated to the service (https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/topics/Page17019.aspx and https://mentalhealthfoundation.ca/text4hope/), electronic media, social media feeds, posters at addiction and mental health clinics, emergency departments and wards, and through word of mouth. The messages were aligned with a cognitive behavioral framework, with content written by mental health professionals and co-authors (V.I.O.A. who is a psychiatrist and M.H. who is a Clinical Psychologist). Most of the messages were adopted or modified from messages used in 2 randomized controlled trials in Alberta,Reference Agyapong, Juhás and Omeje12,Reference Agyapong, Juhás and Mrklas13 and also the Text4Mood program, which reported positive effects on the mental wellbeing of Albertans and achieved high satisfaction rates.Reference Agyapong, Mrklas and Juhás4 The messages were delivered to subscriber cell phones daily at 9 am Mountain Time. Each subscriber received the Text4Hope daily messages for 3 months, with the option to subscribe for an extended 6-mo Text4Mood program on completion of the Text4Hope program. Examples of the Text4Hope text messages include:

-

Put yourself on a media diet. It is important to stay informed, but only check the news and social media intermittently, rather than continuously.

-

Take a moment to notice how you feel right now. Do not judge your emotions or try to change them. Just observe them and see your stress levels reduce.

-

Make yourself a “coping kit.” Include healthy things that help you feel better like music, inspirational messages, or a friend’s number.

Subscribers were sent a link to the online survey by means of the first text messages they received the same day after subscribing to the program and invited to complete a baseline survey that assessed their mental wellbeing using validated scales for stress, anxiety, and depression. Follow-up surveys were sent by means of text messages to all subscribers 6th week and 3rd month after they started receiving daily supportive text messages. Consent was implied if subscribers accessed, completed, and submitted their responses to the online survey. No personally identifiable information apart from subscriber phone numbers was collected, and phone numbers were only used to link the baseline data with the 6th week and 3rd month data for individual subscribers to facilitate measurement of change in the psychometric scales. Data were collected using the Survey Select tool, and extracted data were stored without the identifying phone numbers on a password protected computer. Primary outcome measures at 3rd month were the mean difference in scores on the PSS-10,Reference Cohen, Kamarck and Mermelstein14 GAD-7 scale,Reference Spitzer, Kroenke and Williams15 and the PHQ-9, respctively.Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams16

With a prediction that daily supportive text messages would result in a 25% reduction in mean PSS-10, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 scores at 3rd month from baseline, a population variance of 5.0 for each scale mean score, a 1-sided significance level α = 0.05, and an acceptable difference between sample mean and population mean score for each scale of zero (μ-μ0 = 0), the estimate was that a sample size of 686 would be sufficient to detect mean differences between the baseline and 3rd month PSS-10, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 scores with a power of 80% (β = 0.2). Data analysis was undertaken using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Statistics for Windows, version 26. Paired t-tests were used to assess differences between the mean PSS-10, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 scale scores at baseline and 3rd month for subscribers who completed the instruments at both time points. In addition, Chi-Square test was used to compare prevalence rates for perceived stress, likely GAD, and likely MDD at baseline and 3rd month. Moderate or high perceived stress, likely GAD, and likely MDD were assessed using cut-off scores of PSS-10 ≥ 14, GAD-7 ≥ 10, and PHQ-9 ≥ 10, respectively.Reference Agyapong, Hrabok and Vuong9 There was no imputation for missing data and totals reported represent total responses recorded for each variable.

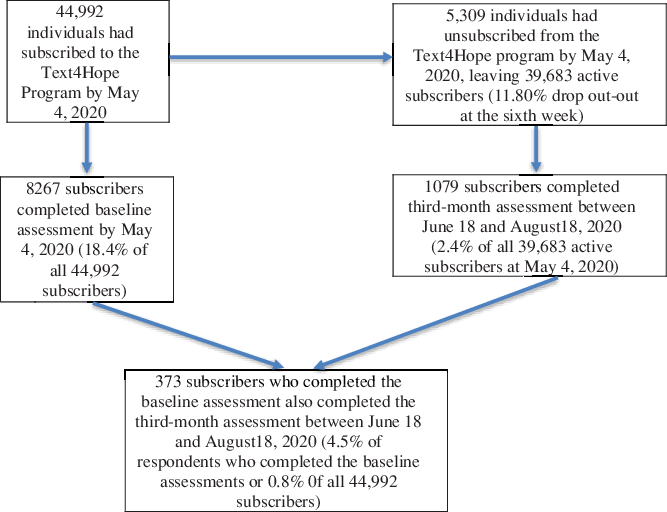

Figure 1 is the study flow chart for individuals who subscribed to Text4Hope between March 24, 2020, and May 4, 2020.

Figure 1. Subscriber flowchart.

Results

The majority of the 1079 subscribers who responded to the 3rd month surveys were female (n = 953; 89.1%), 26 to 60 years of age (n = 824; 78.3%), Caucasian (n = 883; 83.4%), homeowners (n = 638; 71.8%), had postsecondary education (n = 825; 92.1%), and were employed (n = 631; 70.3%).

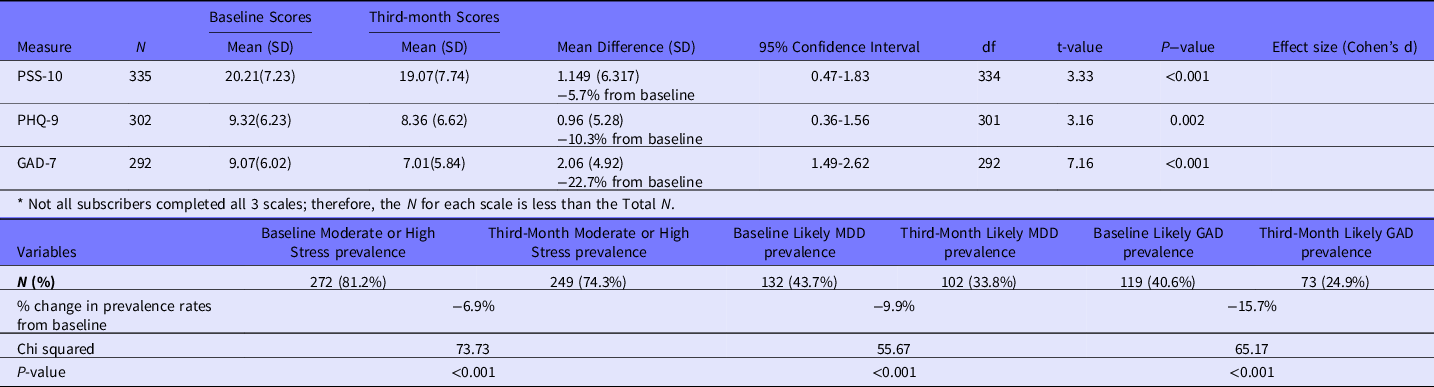

Table 1 presents changes in primary outcome measures after 3rd month compared with baseline. The data indicate that mean scores on each of the PSS-10, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 scales were significantly lower at 3rd month compared with mean scores at baseline, suggesting improvement in stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms. The largest reduction in mean scores at 3rd month compared with baseline scores was on GAD-7 (-22.7%) followed by PHQ-9 (-10.3%) and then PSS-10 (-5.7%). The data of Table 1 indicate statistically significant reductions in the inferred prevalence rates for moderate/high stress, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms comparing baseline and 3rd month assessments. Anxiety was associated with the largest inferred prevalence rate reduction (15.7%).

Table 1. Comparison of the baseline and third-month mean scores on the PSS-10, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 and the prevalence rates of moderate or high stress, likely MDD, and likely GAD*+

+ Moderate or high perceived stress, likely GAD, and likely MDD were assessed using cutoff scores of PSS-10 ≥ 14, PHQ-9 ≥ 10, and GAD-7 ≥ 10, respectively.

Discussion

The impact of COVID-19 on health, way of life, and psychological safety and wellbeing is difficult to overstate. The threat posed by the pandemic to psychological well-being requires use of innovative techniques that can serve the high number of people requiring support while respecting the need to maintain physical distancing. Text4Hope was designed to provide mental health support on a Provincial (Canada) scale during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study examines changes in stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms after 3rd month of receiving Text4Hope messages from this low-cost, evidence-based, scalable, supportive messaging service that was delivered at no direct cost to end users. Although self-reported levels of stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms remained high overall following the study period, both the mean scores for stress, anxiety and depression on standardized scales and the prevalence rates for clinically meaningful stress, anxiety, and depression showed statistically significant reductions (6% to over 20%; P < 0.01). The significant reductions in depression symptoms in particular are consistent with results reported in previous randomized controlled trials of supportive text message interventions for the treatment of major depressive disorder.Reference Agyapong, Ahern and McLoughlin5,Reference Agyapong, Juhás and Omeje12 Significant reductions in anxiety with supportive text messaging were also reported in other randomized controlled clinical trials.Reference Kwan, Chiu and Gan17 This study did not, however, achieve the >25% reduction in stress, depression, or anxiety mean scores at the third month as stated in the study hypothesis. It is possible that levels of stress, anxiety, and depression remain high due to overall media coverage of surges in COVID infections. It is also possible that levels of stress, anxiety, and depression will improve further if subscribers continue to receive supportive text messages for a few more months. This is why subscribers completing the 3rd month intervention are offered information on how to subscribe for 6 additional months of supportive text messages through the Text4Mood program. As of December 20, 2020, over 5000 individuals who had completed the 3rd month Text4Hope program had enrolled on the 6th month Text4Mood program to receive additional support. Evaluation of this extended text support is underway to assess possible incremental benefits to subscribers who opt to join this program.

Limitations of the present study include the very low response rate (4.5% of subscribers who completed baseline assessments and 0.8% of all subscribers), the relatively small sample size and missing data, which could lead to sampling error. It is possible that subscribers who did not participate in the surveys and those who provided incomplete responses might have different 3rd month outcomes compared with those who fully completed both surveys. Furthermore, it is possible that the demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of those who completed the assessments at both time points could be different from those of the large number of Text4Hope subscribers who completed the baseline assessments (n = 8267). However, a related studyReference Nwachukwu, Nkire and Shalaby8 published by this research group, which examined the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the larger sample of subscribers who completed the baseline assessments (n = 8267), had similarities with the baseline characteristics of participants who were studied as part of this 3rd month evaluation of Text4Hope (n = 1079). For example, in terms of demographic characteristics, there were 87.1% versus 89.1% female gender, 77.1% versus 78.3% aged 26-60 y, 82.3% versus 83.4% Caucasians, 85.2% versus 92.1% postsecondary education and 73.4% versus 70.3% employed for all subscribers who completed baseline assessments (n = 8267)Reference Nwachukwu, Nkire and Shalaby8 and subscribers who completed the third-month assessments (n = 1079), respectively. In terms of clinical characteristics at baseline, the mean PSS score was 20.79 (standard deviation [SD] = 6.83; n = 7589) vs. 20.21 (SD = 7.23; n = 335), mean PHQ-9 scores was 9.68 (SD = 5.87; n = 7082) vs. 9.32 (SD = 6.23; n = 302), and the mean GAD score was 9.43 (SD = 6.29; n = 6944) vs. 9.07(6.02; n = 292) for all subscribers who completed baseline assessments and subscribers who completed both the baseline and third-month assessments, respectively.Reference Nwachukwu, Nkire and Shalaby8

Another limitation is the lack of a control group who did not receive the Text4Hope intervention. It is possible, that stress, anxiety, and depression levels would have naturally decreased over time without the intervention. This is plausible as the reported daily mean new COVID-19 infections in Alberta, calculated using an SPSS program from the officially reported daily new infections, had reduced marginally from 104 (SD = 77) during the baseline data collection time period to 78 (SD = 33) during the 3rd month data collection period.18 It should be noted that a natural history of improvement is unlikely, however, as the majority of Canadians recently surveyed reported that their mental health is the same or has worsened since the initial COVID-19 wave.19

Finally, the study used self-reported questionnaires for assessing symptomatology and, therefore, lacked comprehensive assessment to evaluate whether or not symptomatology reported met criteria for clinically significant mental health conditions. The study sample also evidenced multiple protective factors, including high levels of education and employment, and the sample was predominantly female. Therefore, it is unclear how findings from this study may generalize to other demographic groups.

Conclusions

Limitations notwithstanding, the results from this study support the proposal that public health interventions during pandemics may benefit from mental health wellness campaigns aimed at reducing psychological impacts. This study may serve to provide evidence-based support for such policy implementation in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. The research team, therefore, plans to explore national scale-up and implementation of the Text4Hope program in multiple languages to benefit all Canadians. The team will also disseminate this program for adaptation and potential global use through the E-Text4PositiveMentalHealth platform, currently under development, and formation of partnerships with national and regional health authorities and institutions.

Acknowledgments

Support for the project was received from Alberta Health Services and the University of Alberta.

Authors Contributions

V.I.O.A. conceived and designed the study, including the Text4Hope program. M.H., R.S. drafted the initial manuscript with V.I.O.A. A.G., W.V., and S.S. participated in data collection. All authors contributed to study design, revised and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Mental Health Foundation, the Edmonton and Calgary Community Foundations, the Edmonton Civic Employee’s Foundation, the Calgary Health Trust, the University Hospital Foundation, the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, the Royal Alexandra Hospital Foundation, and the Alberta Cancer Foundation. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.