Dietary scores are composite constructs of dietary components used to estimate overall dietary quality(Reference Kant1–Reference Arvaniti and Panagiotakos3). These predefined combinations of foods and/or nutrients provide single operative variables and are considered valuable tools for the analysis of associations between diet quality and health outcomes. Index summary scores, such as the Healthy Eating Index, Diet Quality Index or the Mediterranean diet score (MDS), are based on interpretation of current dietary guidance and on dietary recommendations(Reference Bach, Serra-Majem and Carrasco4, Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou and Bamia5). The traditional MDS was proposed by Trichopoulou et al.(Reference Trichopoulou, Kouris-Blazos and Wahlqvist6) in 1995 as a tool to assess the degree of adherence to the traditional Mediterranean diet. Assessing adherence to the Mediterranean diet has received increasing attention during recent years because of the beneficial effect of this dietary pattern on various aspects of human health(Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou and Bamia5–Reference Schroder9).

Large epidemiological studies have relied primarily on the FFQ approach to estimate habitual individual dietary intake(Reference Molag, de Vries and Ocké10). However, concerns have been raised recently about the ability of participants to provide valid reports of dietary behaviour using these tools, particularly given the demonstration of disparities in diet–disease associations derived from an FFQ compared with alternative instruments(Reference Kristal and Potter11, Reference Freedman, Potischman and Kipnis12). Therefore, assessments of the validity of data derived from an FFQ, or the degree to which the instrument really measures what it attempts to measure, are essential.

Most FFQ validation studies have focused on comparing intake estimates using the instrument with those obtained using a reference method to determine whether it reasonably ranks subjects on the basis of their reported intakes of individual nutrients and/or food groups. However, it is impossible to determine from these data whether the FFQ accurately ranks participants against a composite score composed of multiple nutrients and/or foods, such as the MDS. We are not aware of studies assessing the validity of the MDS across dietary assessment methods. The objective of the present study was to estimate the concurrent and construct validity of two variants of MDS assessment in a subpopulation of a representative Spanish population compared with a series of ten or more unannounced 24 h recalls.

Methods

Subjects

Participants were selected from a population-based cross-sectional survey conducted in Spain in 2005 (REGICOR study)(Reference Grau, Subirana and Elosua13); 150 men and women were selected consecutively. Forty-three participants with incomplete records were excluded; complete dietary data from an FFQ and from at least ten completed 24 h recalls were available for 107 individuals. Participants with complete data did not differ from the initial validation sample with respect to variables potentially related to diet quality, including age, gender and BMI (not shown). The project was approved by the local ethics committee (Comités Éticos de Investigación Clínica – Instituto Municipal de Asistencia Sanitaria, Barcelona, Spain).

Dietary assessment

FFQ

Food consumption was estimated using a validated(Reference Schröder, Covas and Marrugat14) FFQ administered by a trained interviewer. In a 166-item food list including alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages (typical foods in north-eastern Spain), participants indicated their usual consumption and chose from ten frequency categories, ranging from never or <1 time/month to ≥6 times/d. Food items were listed under fourteen food groups: milk and dairy products, cereals and grain products, vegetables, legumes, sausages, oils and fats, eggs, meat and fish, fast food, canned products, fruit, nuts, sweets and desserts, and others (salt and sugar), as well as alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages.

Multiple 24 h recalls

Twelve unannounced 24 h dietary recalls were collected by telephone over a 12-month period by a trained interviewer. At least ten completed recalls were required for inclusion in the analysis. Dietary recalls were conducted on non-consecutive days, including at least five weekdays and one weekend day. Food intake data recorded during the 24 h recalls were grouped into the food-based dietary components of the FFQ for analysis.

Calculation of dietary quality scores

The modified Mediterranean diet score

The modified MDS (mMDS) was calculated according to the tertile distribution of food consumption, with the exception of red wine(Reference Trichopoulou, Orfanos and Norat15, Reference Schröder, Marrugat and Vila16). For cereals, fruit, vegetables, legumes, fish, olive oil and nuts, the lowest tertile was coded as 1, medium as 2 and the highest as 3. For meat (including poultry and sausages) and dairy products, the score was inverted, with the highest tertile coded as 1 and the lowest as 3. Moderate red wine consumption (up to 20 g) was included as a favourable component in the MDS, with a score of 3. Exceeding this upper limit or reporting no red wine consumption was coded as 0. The resulting score ranged from 10 to 30.

The Mediterranean-like dietary score

The Mediterranean-like dietary score (MLDS) was constructed by adding three food groups to the ten components of the mMDS: sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages and added sugars; pastries; and fast food. These food groups were scored inversely. In addition, we omitted high-fat dairy products as a negative component and instead included low-fat dairy products as a beneficial food group. We also excluded poultry and rabbit from the meat and sausage food group. The resulting scores ranged from 13 to 39.

Other variables

Measurements of demographic, socio-economic and lifestyle variables including smoking habits and alcohol consumption were obtained through structured standard questionnaires administered by trained personnel.

Statistical analyses

Differences in continuous variables were compared by the Student t test or the Mann–Whitney U test (for non-normally distributed variables). Categorical variables were tested using the χ 2 goodness-of-fit test.

Spearman's correlation coefficients and cross-classification were used to assess the capability of the FFQ to rank participants according to their food group intake or on the basis of scores obtained on the Mediterranean diet indices. Estimated intakes of individual food groups were also compared across instruments. Cross-classification was carried out using contingency tables of tertile distribution of the FFQ compared with the 24 h recall-derived mMDS and MLDS. The proportion of participants correctly categorized (same tertile) and grossly misclassified (opposite tertiles) was calculated.

The mMDS and MLDS were normally distributed. Therefore, relative agreement of the mMDS and MLDS was assessed by calculating Pearson's product–moment correlation coefficients to compare the 24 h recall scores (reference method) with the participants’ scores on the FFQ (test method).

Two measures might be highly correlated; yet, there could be substantial differences in the two measurements across their range of values. For this reason we additionally analysed absolute agreement between two measurements by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the Bland–Altman method(Reference Bland and Altman17). The Bland–Altman analysis determines the average agreement between two methods by calculating the mean of their differences. The 95 % limits of agreement (LOA) provide an interval within which 95 % of these differences are expected to fall. Agreement between the MDS obtained from the FFQ and those obtained from 24 h recalls was depicted in Bland–Altman plots. A mean agreement of 100 % signified complete agreement between the methods. An LOA between 50 % and 200 % was considered reasonable(Reference Ambrosini, van Roosbroeck and Mackerras18).

A one-sample t test was used to determine the significance of differences between scores derived from the FFQ and those derived from 24 h recalls.

In addition, we analysed possible variations in the level of agreement between methods. Proportional bias indicates that the disparity between test and reference methods (i.e. the mean difference) varies significantly, depending on the magnitude of the mean ratings of dietary indices. For this purpose we performed linear regression analysis, with the mean instrument differences of the mMDS and MLDS constituting the dependent variable and the mean score for the corresponding mMDS and MLDS obtained by the test (FFQ) and reference methods (24 h recalls) constituting the independent variable.

Finally, to assess construct validity, general linear modelling was used to estimate associations between nutrient intakes (dependent variables) derived from 24 h recalls and from the tertile distribution of the mMDS and MLDS calculated from the FFQ (independent variable). Linear trends were tested by including the categorized variable (tertile distribution of the scores) as continuous in this model, and the P value for linear trend was calculated using polynomial contrast for continuous variables. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences statistical software package version 13·0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Differences were considered significant if P was < 0·05.

Results

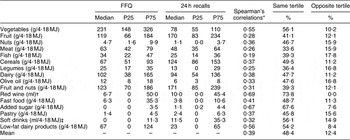

With the exception of education, participants in the validation study did not differ significantly from the rest of the sample (Table 1). Spearman's correlation coefficients for food group intakes estimated from the FFQ and 24 h recalls ranged from 0·19 to 0·69, and were moderate on average (Table 2). We cross-classified food groups into tertiles to evaluate the ability of FFQ and 24 h recalls to rank participants on the basis of categories of intake. On average, 48·4 % of the individuals were grouped into the same tertile on both instruments (ranging from 33·6 % congruence for meat to 73·8 % for red wine). Mean gross misclassification (the percentage of individuals in opposite tertiles for the same food item using the two instruments) for food groups was 13·2 %, with fish being the most frequently misclassified food group (Table 2).

Table 1 Characteristics of the validation study participants and the REGICOR cohort study participants

P25, 25th percentile; P75, 75th percentile; LTPA, leisure-time physical activity; MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

Categorical variables are presented as relative frequencies (95 % CI); continuous variables are presented as mean or median (sd or P25 and P75). Differences in continuous variables were compared using the Student t test or the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were tested using the χ 2 goodness-of-fit test.

*Data are presented as mean and sd.

Table 2 Food intake, Spearman's correlation coefficients and agreement between food intake estimates between the FFQ and 24 h recalls

P25, 25th percentile; P75, 75th percentile

*Spearman's correlation coefficients between food intake obtained through the FFQ and 24 h recalls.

†For cross-classification categorized into 0 ml, 0·1–100 ml and >100 ml of red wine consumption.

‡Sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages.

Pearson's correlation coefficients between the scores derived from the FFQ and 24 h recalls were moderate and good for the mMDS and MLDS, respectively (Table 3). Absolute agreement between the two MDS derived from the FFQ and 24 h recalls was determined by the ICC and LOA methods. The ICC was comparable to Pearson's correlations.

Table 3 Mean, correlation coefficients, between-method agreement and limits of agreement between the FFQ and the 24 h-R

24 h-R, 24 h recalls; LOA, limits of agreement; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient.

*Mean agreement expressed as (FFQ/24 h-R)×100 and 95% CI of mean agreement.

†95 % limits of agreement.

‡Pearson's correlation coefficient.

Mean agreement was calculated, and Bland–Altman's LOA method was used to determine, in absolute terms, the extent of differences between the scores derived from the FFQ and those derived from 24 h recalls. There was little difference in mean agreement, or in LOA, between energy-adjusted v. unadjusted MDS and MLDS (Table 3). The mean percentage of agreement was close to 100 for all measures, with lower LOA above 50 % and upper limits well below 200 % for both indices. Moreover, for both energy-adjusted and non-adjusted scores of both indices, agreement did not vary with the magnitude of ratings (Fig. 1), indicating no proportional bias.

Fig. 1 Mean differences of the modified Mediterranean diet score (mMDS; a) and the Mediterranean-like diet score (MLDS; b) derived from the FFQ and 24 h recalls. Lines are mean differences (- - - -) and upper and lower 95 % limits of agreement (-·-·-·); *regression coefficient and statistical significance of the slope from the linear regression of the mean of the methods against the difference between methods

To analyse construct validity, we hypothesized a priori relationships between higher scores and more favourable intake profiles for fifteen nutrients. We found that, of these fifteen nutrients, 73·3 % and 86·7 % of the 24 h recall-derived intake estimates were associated significantly and in the anticipated direction with tertiles of the FFQ-derived mMDS and MLDS, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4 Nutrient intake by quartile of energy-adjusted dietary scores

*P for linear trend.

Discussion

The present study determined the concurrent and construct validity of two variants of the MDS. Compared with data derived from multiple 24 h recalls spanning a 12-month period, the FFQ showed an adequate capacity to rank participants on the basis of two MDS, the mMDS and the MLDS. LOA was in a reasonable range for both scores. Furthermore, our results indicate sound evidence for construct validity, particularly for the MLDS score, which incorporated several modifications into the traditional MDS.

The Mediterranean diet is a healthy eating pattern associated with better health and lower risk of premature mortality(Reference Trichopoulou, Costacou and Bamia5–Reference Schroder9, Reference Scarmeas, Stern and Tang19–Reference Benetou, Trichopoulou and Orfanos21). Since 1995, adherence to this dietary pattern has been assessed by FFQ-derived composite scores that include foods that are characteristic of the Mediterranean olive grove areas(Reference Bach, Serra-Majem and Carrasco4). Although considered an adequate dietary assessment tool for the estimation of overall diet quality, the MDS has varied between studies because of differences in the scoring criteria(Reference Bach, Serra-Majem and Carrasco4). The present study assessed the validity of a score previously proposed by our group(Reference Schröder, Marrugat and Vila16). In a further adjustment, we omitted inverse scoring for dairy products, including instead low-fat and fat-free (skim) dairy products as healthy foods. We also added fast food, sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages, added sugars and pastry as detrimental foods. Finally, we excluded poultry and rabbit from the meat and sausage food group, scoring these meats separately as a healthy choice. We hypothesized that these changes would increase the accuracy of the construct to measure diet quality. Indeed, overall, both the magnitude of correlations and the proportion of nutrients supporting construct validity were somewhat higher for the modified score than for the original score.

Correlation coefficients for individual food group components of the mMDS and MLDS ranged from 0·19 to 0·69, which is comparable to results from other similar validation studies(Reference Molag, de Vries and Ocké10). In addition, we found a reasonable frequency of agreement and gross misclassification of food groups between methods. Both the mMDS and the MLDS were moderately correlated between assessment methods, indicating that the FFQ reasonably ranks participants according to these diet-quality indices. Unfortunately, the limited literature on concurrent validity of dietary indices makes it somewhat difficult to compare our results with those of other studies. However, a few studies have reported correlations of similar magnitude. Newby et al.(Reference Newby, Hu and Rimm22) reported good correlations (r = 0·66) between the Diet Quality Index Revised derived from an FFQ and those from two 1-week dietary records. Results from Hu et al.(Reference Hu, Rimm and Smith-Warner23) showed the validity of two major dietary patterns derived using principal component analysis from dietary estimates of an FFQ compared with multiple dietary records, with correlations of 0·45–0·58 for the first FFQ.

Ideally, studies on the validity of an FFQ should include multiple methodological tools to determine validity. This permits an accurate interpretation of the strengths and weaknesses of the instrument and provides insight into possible biases of the dietary assessment method. For this reason we assessed the relative validity of the mMDS and MLDS using cross-classification, correlation coefficients, Bland–Altman plots and the LOA method proposed by Bland and Altman(Reference Bland and Altman17). The mean agreement of scores between methods was reasonable in the present study, and LOA was well within the acceptable boundaries of 50 % and 200 %(Reference Ambrosini, van Roosbroeck and Mackerras18). In the present study, the LOA for both scores was in a narrow range compared with levels reported in previous studies for individual nutrients(Reference Ambrosini, van Roosbroeck and Mackerras18, Reference Keogh, Lange and Syrette24); for example, the FFQ under- and overestimated the dietary recall estimates of the energy-adjusted MLDS by only 28 % and 25 %, respectively. Furthermore, Bland–Altman plots showed no significant proportional variations over the range of average ratings for any of the three dietary indices. This means that the errors were not proportional to the ratings.

Construct validity is an additional aspect to be considered in selecting a dietary assessment tool. To address this issue we hypothesized that both of the FFQ-derived dietary quality indices would be positively associated with a favourable nutrient intake profile estimated by 24 h recalls. Intakes of K, Mg, folic acid, vitamins C and E, phytosterols and dietary fibre were positively associated with mMDS ratings. In addition to these nutrients, inclusion in the MLDS of additional detrimental foods such as fast food, added sugars, sugar-sweetened soft drinks and pastry – as well as modification of the dairy component – improved the construct validity of the score and yielded a positive association with trans fatty acids and Ca.

An inherent limitation of our study, and of all validation studies using multiple dietary recalls or records as the reference method, is that these methods themselves are not error free. Errors in the two methods may be correlated. However, the measures used in the present study have important strengths, including the use of unannounced recalls spanning a 12-month period, enabling us to capture seasonal differences in intake.

We conclude that the FFQ accurately allocates participants across the distribution of ratings of the mMDS and MLDS intakes. For both scores, the construct estimates were valid compared with multiple recalls, and the LOA was in a reasonable range with no indication of bias.

Acknowledgements

The present research was supported by a grant from Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER; Grant no. 2FD097-0297-CO2-01) and by parts of grants from Spain's Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, Instituto de Salud Carlos III FEDER (Grant no. PI080439), Red HERACLES RD06/0009 and by a joint contract of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the Health Department of the Catalan Government (Generalitat de Catalunya; CP 03/00115). The CIBERobn is an initiative of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. The authors have no conflict of interest to declare. A.A.B.-A. conducted the analyses and prepared the manuscript; H.Sc. designed the study; M.A.M., J.M.B.-D., M.A.R.A., C.S., J.M., M.-I.C., H.S., A.L. and H.Sc. provided their expertise in data analysis and in interpretation and discussion of results and made substantial suggestions to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. The authors appreciate the English revision made by Elaine Lilly, PhD (Writers First Aid).