Introduction

It matters how people view the police—the gatekeepers of the criminal justice system and representatives of the power of the state. Those who lack faith in the police or who see the police as biased feel less safe in their own neighborhood (e.g., Drakulich Reference Drakulich2013). People’s experiences with and views about the police shape their broader views of the government and the civic body, as well as their participation in it (Drakulich et al., Reference Drakulich, Hagan, Johnson and Wozniak2017, Reference Drakulich, Wozniak, Hagan and Johnson2020; Lerman and Weaver, Reference Lerman and Weaver2014), evoking a sense of social and legal estrangement (Bell Reference Bell2017; McLemore Reference McLemore2019). Perceptions of police inefficacy or injustice may even increase crime itself by reducing willingness to act informally against crime or by encouraging extralegal resolutions to problems (Anderson Reference Anderson1999; Drakulich and Crutchfield, Reference Drakulich and Crutchfield2013; Kirk and Papachristos, Reference Kirk and Papachristos2011).

It is notable, then, that the most consistent finding in research on views about the police is the identification of substantial differences in these views across racial lines. A recent meta-review of ninety-two studies found that people of color—and particular Black Americans—held consistently lower evaluations of the police than non-Hispanic White Americans across a wide variety of different dimensions of views about the police (Peck Reference Peck2015). In particular, Black Americans are more likely to view the police as racially biased and unfair (e.g., Hagan et al., Reference Hagan, Shedd and Payne2005), and less likely to express overall support or confidence in the police (e.g., Ekins Reference Ekins2016; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Wilson, Maguire and Lowrey-Kinberg2017).

These racial differences in views of the police have received substantial public attention for decades (e.g., Braga et al., Reference Braga, Brunson and Drakulich2019; Krauss Reference Krauss1994). Statements about the need to improve police-community relations, particularly for communities of color, appear on the websites of nearly every organization that works with or does research on the police (e.g., Law Enforcement Action Partnership, 2017; Thomas Reference Thomas2016), and these issues were central concerns for the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (President’s Task Force 2015). The issue has received particular attention as the Black Lives Matter social movement has sought to bring greater attention to issues of police violence and anti-Black racism (Black Lives Matter, n.d.; Garza Reference Garza and Hobson2016).

The key question is what explains this considerable racial gap in views about the police. A substantial portion of the work trying to explain views about the police has focused on contact with the police. In general, Black Americans have more negative experiences with the police (e.g., Baumgartner et al., Reference Baumgartner, Epp and Shoub2018; Crutchfield et al., Reference Crutchfield, Skinner, Haggerty, McGlynn and Catalano2012; Gelman et al., Reference Gelman, Fagan and Kiss2007; Voigt et al., Reference Voigt, Camp, Prabhakaran, Hamilton, Hetey, Griffiths, Jurgens, Jurafsky and Eberhardt2017) and are more likely to be shot or killed by the police while unarmed (e.g., Correll et al., Reference Correll, Park, Judd, Wittenbrink, Sadler and Keesee2007; Nix et al., Reference Nix, Campbell, Byers and Alpert2017; Ross Reference Ross2015). These negative experiences translate to more critical evaluations of the police (e.g., Flexon et al., Reference Flexon, Lurigio and Greenleaf2009; Skogan Reference Skogan2006). Young Black men in particular tend to accumulate negative experiences with the police which shape their more negative evaluations of the police (e.g., Brunson Reference Brunson2007), and vicarious experiences—the experiences of friends and family members—appear important to shaping views about the police more broadly (e.g., Gau and Brunson, Reference Gau and Brunson2010; Warren Reference Warren2011).

More positive views about the police are the goal of research, advocacy, and policy-work on procedural justice—the idea that police can improve how they are viewed by the communities they work in by demonstrating neutrality, encouraging voice or participation, treating people with respect and dignity, and conveying trustworthy motives (e.g., Mazerolle et al., Reference Mazerolle, Bennett, Davis, Sargeant and Manning2013; Schulhofer et al., Reference Schulhofer, Tyler and Huq2011; Tyler Reference Tyler2017). On the other side, when people view the police as biased and untrustworthy, the concern shared by these perspectives is that people may not cooperate with the police or obey the police or the law (Tyler Reference Tyler2006; Tyler and Fagan, Reference Tyler and Fagan2008; Tyler and Jackson, Reference Tyler and Jackson2014). Put simply, this perspective highlights positive views about the police as the ideal or goal, and negative views or perceptions of police bias as a problem to be addressed. Applied to racial differences in views about the police, the implication is that the generally favorable views about the police held by the average white American is the goal, and that we should be concerned that bad experiences with the police are preventing Black Americans from having similarly positive views.Footnote 1

However, we argue people’s views about the police may be rooted in more than personal or vicarious experiences with the police. Views about the police are social and political constructions, the target of collective action framing efforts. This is especially the case when the police—and racial biases in policing specifically—are relevant to political and social conflict. In both the Civil Rights and Black Lives Matter Eras, movement actors sought to bring problematic and biased police behavior to public attention (e.g., Taylor Reference Taylor2016). In response to Black Lives Matter, Blue Lives Matter counter-framing efforts sought to rally support for the police. When racial gaps in police treatment receive public attention—and when both these gaps and the police themselves become the subject of partisan political debate (Healy and Burns, Reference Healy and Burns2016)—views about the police are not likely to be just the product of experiences with the police but will also be related to views of race and political identities. Thus, we join a growing number of studies examining how views about the police may be rooted in political and racial attitudes (Callanan and Rosenberger, Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Matsueda and Drakulich, Reference Matsueda and Drakulich2009; Peffley and Hurwitz, Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010; Wozniak Reference Wozniak2016), and in doing so we recommend a subtle but important shift in framing the questions we ask about public views of the police.

While many prior studies focus on explaining less favorable views about the police among Black Americans, we suggest a shift in this focus to explaining the remarkably more favorable views about the police among many White Americans. Specifically, in the aftermath of a series of widely covered police shootings of Black Americans, a civil rights social movement focused on police racial bias, and a national presidential election in which the police and race become a debated issue, what does it mean to support the police? Rather than focus on a deficit in enthusiasm for the police among Black Americans, we suggest it is worth more directly considering the deficit in critical views of the police among White Americans. To this end, we investigate whether people’s views about the police are rooted in their racial and political views, and whether these views help explain some of the general racial gap in views about the police.

Explaining Views About the Police

A large number of prior studies focus on explaining views about the police as a function of experiences with the police. Given the generally more negative experiences Black Americans have with the police, this has obvious value in understanding why Black Americans view the police with greater concern. This explanation also has clear policy implications: that police policies and practices must be changed to improve the experiences Black Americans have with the police (e.g., President’s Task Force 2015). In this light, lower evaluations of the police among Black Americans are rational reactions to a worse set of experiences with the police relative to White Americans.Footnote 2

However, this approach treats generally high support among White Americans as the default, explaining it merely as a lack of erosion from negative experiences with the police. In reversing the question, we treat it instead as something worth explaining directly. To do so we develop an explanation that goes beyond the mere absence of contact with the police.

Instead, we suggest that people’s views about the police are at least in part social and political constructions (e.g., Baranauskas and Drakulich, Reference Baranauskas and Drakulich2018; Beckett and Sasson, Reference Beckett and Sasson2004; Berger and Luckmann, Reference Berger and Luckmann1990; Chermak and Weiss, Reference Chermak and Weiss2005; Ericson Reference Ericson1989; Kasinsky Reference Kasinsky1995; Rafter Reference Rafter1990). Views about the police have symbolic and expressive meaning (Jackson and Bradford, Reference Jackson and Bradford2009; Jackson and Sunshine, Reference Jackson and Sunshine2007). People, for instance, display Black Lives Matter signs in their yards or thin blue line flags on their cars. The views themselves are also the targets of active and contested collective action framing efforts (Benford and Snow, Reference Benford and Snow2000; Goffman Reference Goffman1974). We expect that views about the police are shaped by other political and racial views, especially in the context of racial biases in policing receiving public attention in ways that are contested across political party lines.

This may happen, in part, naturally: beliefs about whether the police act in racially biased ways are likely to be rooted in broader understandings of the meaning and importance of race, for instance. But these connections may also be actively encouraged by social movement actors seeking to rally support around particular understandings of the issue (Benford and Snow, Reference Benford and Snow2000), particularly social movements which “shape, and are shaped by, conceptions of race and ethnicity” (Owens et al., Reference Owens, McVeigh, Cunningham, Snow, Soule, Kriesi and McCammon2019, p. 566), including both racist (e.g., Cunningham Reference Cunningham2013; McVeigh Reference McVeigh2009) and anti-racist movements (e.g., Taylor Reference Taylor2016). Movement actors seek to strategically design frames that construct a particular understanding of an issue, assign blame for problems, and point towards specific solutions (Benford and Snow, Reference Benford and Snow2000) in a way that resonates broadly (Snow and Benford, Reference Snow and Benford1988) through strategies such as building bridges between ideologically congruent frames or by tapping into existing cultural beliefs or narratives (Snow et al., Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986). For example, Black Lives Matter organizations may seek to emphasize broad individual rights themes rather than narrower identity issues to promote their framing of racial inequality and police bias (Tillery Reference Tillery2019). On the other side, some political actors appeared to tap into racial anxieties in a counter-framing in support of the police (Drakulich et al., Reference Drakulich, Wozniak, Hagan and Johnson2020).

Politics

There are several reasons to expect that people’s political identities may influence their views about the police. While it may seem obvious that people would pick the politician or party that best fits their political positions, there is evidence that the reverse is true: that people pick a politician or party and then adopt the corresponding policy views (Lenz Reference Lenz2012). This appears to have happened during the 2016 election on issues related to Black Lives Matter and immigration (Enns and Jardina, Reference Enns and Jardina2021). Political actors may also seek to actively shape public understandings of the police through framing processes, including building bridges to congruent frames within a political ideology or amplifying core symbolic values or positions relevant to the frame. This is significant because many political actors took explicit positions on the police as Black Lives Matter protests took place across the country. In particular, many Republican and conservative political actors expressed pro-police rhetoric (Alcindor Reference Alcindor2016; Campbell Reference Campbell2015; Parker Reference Parker2016) while some Democratic and liberal political actors expressed support for the Black Lives Matter movement and its core concerns (Bouie Reference Bouie2015; Glanton Reference Glanton2016; Grawert Reference Grawert2016).

However, political identities may also be endogenous to some of the other factors considered here, in particular racial animus and racial resentment (Drakulich Reference Drakulich2015a; Matsueda et al., Reference Matsueda, Drakulich, Hagan, Krivo, Peterson, Aldrich and McGraw2011). Historically, the Republican ‘southern strategy’ was an explicit effort to recruit voters uncomfortable with changing race relations to the party (Beckett and Sasson, Reference Beckett and Sasson2004; Tonry Reference Tonry2011). More recently, racial animus or racial resentment appeared to play a role in vote choice in the 2008 election (e.g., Krupnikov and Piston, Reference Krupnikov and Piston2015), the rise of the tea party (e.g., Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016; Tope et al., Reference Tope, Pickett and Chiricos2015), and the 2016 election (Drakulich et al., Reference Drakulich, Hagan, Johnson and Wozniak2017, Reference Drakulich, Wozniak, Hagan and Johnson2020; Sides et al., Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018).

Racism

When accusations of racial disparities in policing receive substantial public attention, views about the police may also be shaped by understandings of race and race relations. Several different kinds of racial views may matter, each of which has different implications for understanding racial differences in views about the police.

First, views about the police may be shaped by racial crime stereotypes. Stereotypes of Black Americans as dangerous and criminal extend back to the arrival of the first African slaves in the Americas in the early 1600s. In “illegally resist[ing] legal slavery” they were “stamped from the beginning as criminals” (Kendi Reference Kendi2017). The legal institution of chattel slavery, the Slave Codes, the Fugitive Slave Act, the Black Codes, and the Jim Crow laws all explicitly criminalized Blackness—creating a list of crimes that by definition only Black Americans could commit (e.g., Alexander Reference Alexander2020; Blackmon Reference Blackmon2009; Kendi Reference Kendi2017). After the end of legal segregation and discrimination, new laws and policies designed to disproportionately impact Black Americans replicated the racial control and exploitation functions of legal segregation and discrimination, but in superficially non-racial terms (e.g., Alexander Reference Alexander2020; Baptist Reference Baptist2016; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2018; Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017; Taylor Reference Taylor2019; Wacquant Reference Wacquant, Blomberg and Cohen2003). This includes police policies and practices that disproportionately target Black over White criminal behavior (e.g., Beckett et al., Reference Beckett, Nyrop and Pfingst2006),Footnote 3 as well as sentencing policies including the infamous 100:1 crack-cocaine disparity (Coyle Reference Coyle2002). The result is disproportionate involvement in the criminal justice system, and a corresponding emphasis on the statistics of Black criminality, which Khalil Gibran Muhammad (Reference Muhammad2010) points out began within decades of the end of legal slavery.

Consequently, stereotypes of Black Americans as criminal or violent are pervasive. Americans tend to overestimate the amount of crime in communities with more Black residents (Quillian and Pager, Reference Quillian and Pager2001), a phenomenon explained in part by explicitly held stereotypes of Black Americans as more criminal (Drakulich Reference Drakulich2012). Many Americans possess a racial typification of crime, viewing it as a primarily Black phenomenon (Chiricos et al., Reference Chiricos, Welch and Gertz2004; Pickett et al., Reference Pickett, Chiricos, Golden and Gertz2012). Katheryn Russell-Brown (Reference Russell-Brown1998) describes an irrational fear of young Black men in particular, which she describes as the ‘myth of the criminalblackman’ (see also Young Reference Young, Peterson, Krivo and Hagan2006). Those who believe that Black Americans are more criminal or violent may be more likely to see disproportionate unjustified stops of or excessive force against Black citizens as justified. They may express support for the police even in a moment when the police are accused of racial biases. However, many theories of racism suggest that specific prejudicial attitudes like stereotypes are the product of deeper concerns about racial group positions (Blumer Reference Blumer1958) or a justification for existing inequalities or discriminatory practices.Footnote 4 In other words, these views may be more symptom than disease.

Second, and perhaps most simply, views about the police may be influenced by racial affect. A variety of work emphasizes the importance of racial group affect, often tied to racial closure or segregation. W. E. B. Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1899) discusses a “natural repugnance to close intermingling” (p. 394) of Black Americans by White Americans as the antecedent of discrimination. A half-century later, the contact hypothesis describes the in-group processes that lead to negative intergroup feelings and suggests positive intergroup contact as the solution (Allport Reference Allport1954). Those White Americans who lack affinity for Black Americans may be less likely to believe or be concerned by stories of police racial bias, and those who dislike or hate Black Americans may even welcome the thought of police abuses. However, as with stereotypes, a lack of affinity or presence of hate may be the product rather than source of racial discrimination (e.g., Kendi Reference Kendi2017). Additionally, racial animus may reflect an overt and explicit racism that appears to have declined significantly since the Civil Rights Era (Krysan and Moberg, Reference Krysan and Moberg2016; Schuman et al., Reference Schuman, Steeh and Bobo1985).

Third, views about the police may be the product of more instrumental racial views (e.g., Blumer Reference Blumer1958). A long history of policies establishing the legal exploitation and racial separation of Black Americans were justified with an explicitly racial logic emphasizing the inherent inferiority of Black people (e.g., Alexander Reference Alexander2020; Blackmon Reference Blackmon2009; Bobo and Smith, Reference Bobo, Smith, Katkin, Landsman and Tyree1998; Kendi Reference Kendi2017; Wacquant Reference Wacquant, Blomberg and Cohen2003). The Civil Rights movement challenged the laws codifying racial discrimination and the explicit racial logic justifying it. This challenge necessitated the formation of a new racial logic (e.g., Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997; Jackman and Muha, Reference Jackman and Muha1984) to justify a new set of policies and practices that served to maintain racial inequalities (e.g., Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2018; Rothstein Reference Rothstein2017; Taylor Reference Taylor2019). This new racial logic, described as modern, symbolic (Sears Reference Sears, Katz and Taylor1988; Sears and McConahay, Reference Sears and McConahay1973), laissez-faire (Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997), or colorblind racism (Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2018) still serves to justify racial inequalities but does so while explicitly eschewing race.

This racial logic—a dismissal of the relevance of slavery and discrimination, a belief that racial disparities are the product of Black deficiencies, and a resentment of efforts to ameliorate inequalities—may be relevant to views about the police. Part of the logic is an intentional dismissal of historical and contemporary discrimination. Consistent with this, adherents may dismiss the existence of police racial bias. Those holding these views may also express strong support for the police, who serve as symbolic defenders of the racial order, and who have also long been used as a racist dog whistle, a way of signaling to those uncomfortable with challenges to the racial status quo without explicitly invoking race (Drakulich et al., Reference Drakulich, Wozniak, Hagan and Johnson2020; Haney-López Reference Haney-López2014). Consistent with the modern racism logic, this eschews explicit references to race, while still supporting an institution engaged in the symbolic defense of the racial order.

These three forms of racism have different implications. If crime stereotypes alone are relevant to views about the police, this may reflect a stigma rooted in the historical correlations between communities of color and social problems rather than one rooted in prejudice or racial hostility (e.g., Sampson Reference Sampson2009, and see discussion in Drakulich and Siller, Reference Drakulich, Siller, Johnson, Warren and Farrell2015). As Erving Goffman (Reference Goffman1963) suggests, stigma may be driven more by ignorance than intentions of harm. If views about the police were solely related to a lack of affinity for Black people, this tells a more problematic story, though if this lack of affinity is the result of a lack of positive interracial contact (e.g., Allport Reference Allport1954), this may also be a story rooted in ignorance rather than intention. Alternatively, if the modern racist logic—a racial resentment of Black Americans—is relevant to views about the police, this suggests a story rooted less in mere ignorance and more in group interest. In this last explanation, racial stereotypes and animosities may exist as symptoms of or justifications for more instrumental racial concerns.

Prior Research: What Do We Know About Views About the Police?

A substantial volume of research exists on how civilians view the police, from which several clear stories emerge. First, as described in the introduction, it matters how people view the police. The consequences of a lack of faith in the police—at the individual or community-level—are central to work on police injustice (e.g., Hagan and Albonetti, Reference Hagan and Albonetti1982), procedural justice (e.g., Tyler Reference Tyler2006), legal cynicism (e.g., Kirk and Papachristos, Reference Kirk and Papachristos2011), and legal estrangement (Bell Reference Bell2017), as well as to broader work on marginalization or people’s trust in government more generally (e.g., Lerman and Weaver, Reference Lerman and Weaver2014).

Second, views about the police are multi-dimensional. Work has focused on perceived biases in police behavior particularly across racial lines (e.g., Weitzer and Tuch, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2002) and perceptions of police misconduct, misbehavior, or corruption (e.g., Weitzer and Tuch, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2004). Collectively, bias and misconduct—whether the police disproportionately stop without justification or use excessive force against some group of people, for instance—constitute perceived police injustice (Hagan et al., Reference Hagan, Shedd and Payne2005; Hagan and Albonetti, Reference Hagan and Albonetti1982). Still other work investigates trust in the police or perceptions of police legitimacy (e.g., Tyler Reference Tyler2005), perceptions of police effectiveness or satisfaction (e.g., Dowler and Sparks, Reference Dowler and Sparks2008), or more general assessments including support for or favorability towards the police (e.g., Ekins Reference Ekins2016). Collectively, these different dimensions may represent an interpretive package of related frames of the police (Benford and Snow, Reference Benford and Snow2000; Drakulich Reference Drakulich2015a; Gamson Reference Gamson1988; Gamson and Modigliani, Reference Gamson and Modigliani1989).

Third, views about the police are highly stratified along racial lines (Peck Reference Peck2015). There are large differences in particular between White and Black Americans (e.g., Brunson and Weitzer, Reference Brunson and Weitzer2009; Warren Reference Warren2011; Weitzer Reference Weitzer2000; Weitzer and Tuch, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2002, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2004, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2006). Beyond individual racial differences, the racial composition of communities appears to matter (e.g., Brunson and Weitzer, Reference Brunson and Weitzer2009). For example, critical views of the police are more common in communities with more Black residents but these critical views are not exclusive to Black residents within those communities (Drakulich Reference Drakulich2013; Drakulich and Crutchfield, Reference Drakulich and Crutchfield2013; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Sun and Triplett2009).

Fourth, a substantial literature suggests experiences with the police tend to be relevant to views about the police. A variety of work suggests that personal experiences with the police influence views about the police (Brunson Reference Brunson2007; Brunson and Weitzer, Reference Brunson and Weitzer2009; Callanan and Rosenberger, Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Dowler and Sparks, Reference Dowler and Sparks2008; Gau and Brunson, Reference Gau and Brunson2010; Hagan et al., Reference Hagan, Shedd and Payne2005; Weitzer and Tuch, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2002, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2004, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005; Wortley et al., Reference Wortley, Hagan and Macmillan1997). Although individual incidents appear impactful, the accumulation of these experiences may matter more (Brunson Reference Brunson2007). Additionally, vicarious experiences—the accounts of families and friends who have had encounters with the police—also influence views about the police (Callanan and Rosenberger, Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Gau and Brunson, Reference Gau and Brunson2010; Warren Reference Warren2011). Consistent with this narrative, the procedural justice literature suggests a lack of racial differences in the relationship between procedural justice and legitimacy or cooperation, and in the meaning of fairness, implying that differences are rooted instead in the differential likelihood of being treated in a procedurally unjust manner (Tyler Reference Tyler2005; Tyler and Huo, Reference Tyler and Huo2002).

Fifth, a smaller literature suggests political views may be relevant to views about the police. Those who identify either as a Republican or as conservative appear less likely to view the police as biased or unjust (Callanan and Rosenberger, Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Matsueda and Drakulich, Reference Matsueda and Drakulich2009; Pickett et al., Reference Pickett, Nix and Roche2018; Wozniak et al., Reference Wozniak, Drakulich and Calfano2020), less likely to believe they use excessive force or otherwise misbehave (Callanan and Rosenberger, Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Wozniak et al., Reference Wozniak, Drakulich and Calfano2020), and generally like, support, or express confidence in the police (Callanan and Rosenberger, Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Stack and Sun1998; Fine et al., Reference Fine, Rowan and Simmons2019; Wozniak et al., Reference Wozniak, Drakulich and Calfano2020; Zamble and Annesley, Reference Zamble and Annesley1987). Those identifying as Republican or conservative are also more likely to hold related views, such as supporting police use of force or racial profiling (Gabbidon et al., Reference Gabbidon, Penn, Jordan and Higgins2009; Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Brazier, Forrest, Ketelhut, Mason and Mitchell2011; Silver and Pickett, Reference Silver and Pickett2015), and opposing Black Lives Matter (Drakulich et al., Reference Drakulich, Wozniak, Hagan and Johnson2021; Updegrove et al., Reference Updegrove, Cooper, Orrick and Piquero2020).

Sixth, a smaller (relative to work on experiences with the police) but particularly important literature suggests racial views may be relevant to views about the police. Several studies look directly at the question of the role of racism in people’s views of whether the police are biased (Matsueda and Drakulich, Reference Matsueda and Drakulich2009; Peffley and Hurwitz, Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010), or engage in problematic behavior like excessive force, or generally support or have confidence in the police (Wozniak Reference Wozniak2016). Some work does show evidence of a role for some measure of racial animus or racism for related views, such as support for the idea of police use of force (Barkan and Cohn, Reference Barkan and Cohn1998; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Corra and Jenks2016; Carter and Corra, Reference Carter and Corra2016; Johnson and Kuhns, Reference Johnson and Kuhns2009; Pickett Reference Pickett2016; Silver and Pickett, Reference Silver and Pickett2015), the justifiability of police shootings (Strickler and Lawson, Reference Strickler and Lawson2020), support for protest policing (Metcalfe and Pickett, Reference Metcalfe and Pickett2022), as well as the desire to increase spending on law enforcement (Drakulich Reference Drakulich2015b; Matsueda and Drakulich, Reference Matsueda and Drakulich2009; Morris and LeCount, Reference Morris and LeCount2020). There is a larger number of studies suggesting the relevance of racial views to punitive attitudes (e.g., Bobo and Johnson, Reference Bobo and Johnson2004; Drakulich Reference Drakulich2015b; Johnson Reference Johnson2008; Unnever and Cullen, Reference Unnever and Cullen2010). Research that does focus on the role of racism rarely compares multiple potential dimensions of racism (though see Drakulich Reference Drakulich2015b; Matsueda and Drakulich, Reference Matsueda and Drakulich2009).

We see these last two emerging literatures—exploring the political and racial forces shaping views about the police—as reflecting a fundamentally different question than the first. It is for this reason we are suggesting a subtle but important reframing of the question, moving from a focus on a Black deficit in enthusiasm for the police on average to more intentional efforts to explain the unusually positive average views—and the deficit on average in critical views—about the police among White Americans.

Research Questions

We are interested in factors that help explain views about the police. More specifically, we are interested in those factors which help explain differences in views about the police between Black and White Americans—that mediate the role of race in explaining views about the police.

We are interested in people’s views about the police at a specific moment in time—in the midst of a social movement focused broadly on racial equality and specifically on police treatment of Black citizens (Cobbina Reference Cobbina2019; Garza Reference Garza and Hobson2016). Given this, we focus on two dimensions of views about the police: one specific to these issues, and one more general. First, we are interested specifically in how people see the police acting along racial lines; whether they view them as misbehaving in racially discriminatory ways. This kind of question is central to prior work on perceived police injustice (e.g., Hagan and Albonetti, Reference Hagan and Albonetti1982; Matsueda et al., Reference Matsueda, Drakulich, Hagan, Krivo, Peterson, Aldrich and McGraw2011), and the question of perceived bias is relevant to work on procedural justice (e.g., Sunshine and Tyler, Reference Sunshine and Tyler2003; Tyler Reference Tyler2017). Second, we are interested in a more general affective support—whether people generally feel favorably toward the police or not, a measure used in prior work focused variously on explaining views of police use of force, procedural justice, and political behavior (Drakulich et al., Reference Drakulich, Wozniak, Hagan and Johnson2020; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Thompson and McMahon2017; Mason Reference Mason2018; Peyton et al., Reference Peyton, Sierra-Arévalo and Rand2019).

As discussed above, we are interested in investigating two broad sets of explanations for these views. The first is that people’s views about the police will be influenced by their experiences or contact with the police. We focus on three possible dimensions. First, the simple experience of being stopped and questioned by the police. Second, vicariously experienced stops someone hears about from family or friends. Third, police-citizen interactions that end in more severe consequences for the citizen, such as an arrest or even time in jail or prison. We also explore a potential role for racially discriminatory experiences with the police in the Appendix.

These factors, however, are best suited to explain the Black ‘deficit’ in positive views about the police. For this reason, we also seek to explore how views about the police may reflect political identities or feelings about race or understandings of race relations—explanations better suited to explaining the unusually positive average views about the police among White Americans. For politics, we explore the role of political ideology as well as party identification. For views on race, we explore each of the dimensions outlined above: stereotypes about Black violence, racial affinity, and racial resentment (a view involving a dismissal of the relevance of historical or contemporary discrimination, the blaming of racial inequalities on Black deficiencies, and a resentment of efforts to ameliorate those inequalities).

Data, Measures, and Methods

Data

To explore the role of politics and racial attitudes in views about the police, we focus on a time when the police—and specifically the question of racial discrimination by the police—were a part of the national conversation: the 2016 presidential election. A series of deaths of Black Americans at the hands of the police between 2014 and 2016 received substantial public attention and sparked mass protests (Gately and Stolberg, Reference Gately and Stolberg2015; Thorsen and Giegerich, Reference Thorsen and Giegerich2014), out of which emerged organizing work by a diverse coalition broadly under the Black Lives Matter banner (Boyles Reference Boyles2019; Cobbina Reference Cobbina2019). These issues made their way first to the presidential primaries and then to the general election campaigns during the run-up to the 2016 presidential election.

We explore our questions in data from two different surveys. Both surveys were conducted by the same organization around the 2016 election. One is designed to be nationally representative while the other is weighted to reflect the national population on key demographic and political dimensions. The surveys differ in their sampling strategies, interview formats, and in the precise wording of key questions. This allows us to replicate the results within a single paper and protect against false positives (Murayama et al., Reference Murayama, Pekrun and Fielder2014; and see Pickett et al., Reference Pickett, Chiricos, Golden and Gertz2012; Quillian and Pager, Reference Quillian and Pager2001; Roche et al., Reference Roche, Pickett and Gertz2016).

The first survey—the ANES 2016 Pilot Survey (American National Election Studies, 2016) was conducted in late January 2016, just before primary voting began in early February. The ANES collected surveys from 1200 respondents and included weights designed to make the sample representative of the larger population of U.S. citizens aged eighteen or older on the basis of age, gender, race-ethnicity, education, region, and party identification (all results include these weights). The survey was conducted over the internet drawing on respondents from an existing panel.Footnote 5

The second survey is the from the 2016 American National Election Studies Time Series Survey (American National Election Studies, 2017), conducted in two waves: the first in the two months prior to the general election and the second in the two months after the election (DeBell et al., Reference DeBell, Amsbary, Meldener, Brock and Maisel2018). The post-election interview included 1059 face-to-face interviews and 2590 online interviews. All models include a control for the mode of interview and are weighted to adjust for sample attrition and ensure the sample reflects the U.S. 18-plus population.

As our interest is specifically in explaining the differences in views between White and Black Americans, for simplicity and space we restrict both samples to those individuals who identify as non-Hispanic White or Black.Footnote 6

Measures

Perceptions of the Police. First, we are interested in whether people believe that the police regularly act in racially discriminatory ways toward Black versus White Americans. In the ANES 2016 Pilot Study (APS), this is captured by a combination of five separate measures. Two measures ask respondents how often they think police officers stop White and Black people, respectively, on the street without good reason, each on five-category scales from never to very often. We subtract the first of these from the second to produce a measure of how much more people think the police stop Black relative to White people. We do the same for two questions on identical scales asking respondents how often they thought the police used “more force than is necessary under the circumstances” when dealing with White and Black people, respectively. A final question is posed more broadly, asking respondents in general about whether the police treat ‘Whites’ or ‘Blacks’ better on a seven-point scale. Although we initially examined these three measures separately, they were highly related to each other, seeming to reflect a single latent perception of police racial discrimination. As such, we constructed a final measure as the average of standardized scores for the three measures.Footnote 7

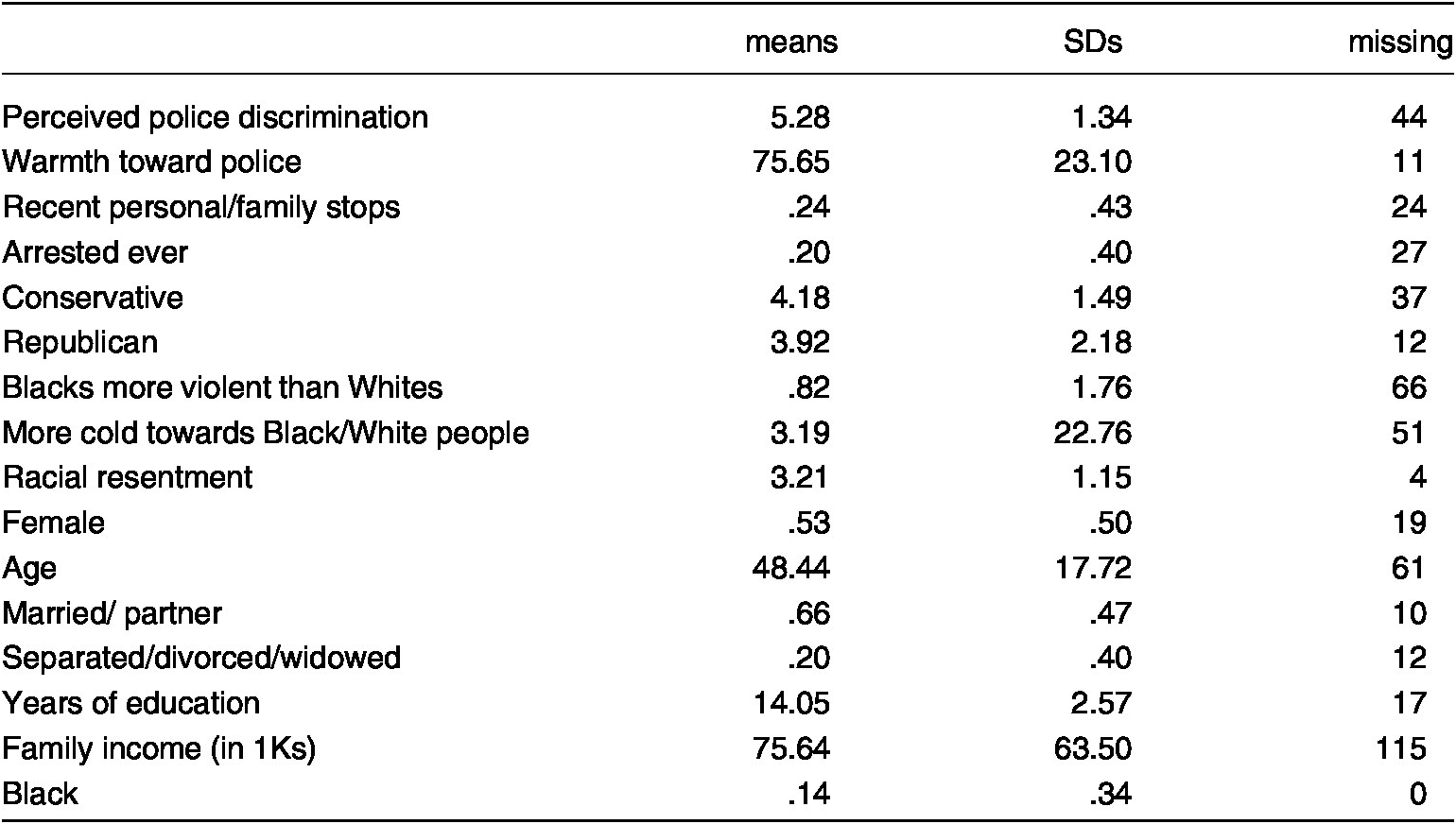

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and the number of missing values for each measure used in the APS. For the measures of perceived discrimination in police stops and use of force, the small but positive mean suggests the average respondent falls somewhere between believing the police are not at all discriminatory (a score of zero) and believing they discriminate a little more against Black versus White people (the measures range from -4:4). Similarly, the mean just above 5 in the general police discrimination measure suggests the average respondent believes the police treat White people “a little” better than Black people. The fourth measure—“perceived police discrimination (combined)”—is the average of the standardized scores for the previous three.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for APS

Total possible N=1010

The ANES 2016 Time Series Study (ATS) includes just the third and broadest question about police discrimination: whether the police, in general, “treat Whites better than Blacks, treat them both same, or treat Blacks better than Whites” on a seven point scale ranging from treating Black people much better to treating White people much better. The average response is similar to that in the APS: an agreement that the police treat White people “a little” better than Black people (Table 2).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for ATS

Total possible N=2974

For our second outcome of interest, we move from specific assessments of police racial bias to more general feelings of support or affection for the police. Both surveys use identical questions to capture general feelings of affective support for the police: a “thermometer scale” question, a common format in political science research to gauge affective support for individuals, groups, or issues (Nelson Reference Nelson and Lavrakas2008). Respondents were asked to rate their feelings toward a list of groups on a scale ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 representing very cold and unfavorable feelings and 100 representing very warm or favorable feelings. Among these, respondents were asked specifically how warmly or coldly they felt toward “the police.” In both surveys, respondents rated the police, on average, relatively warmly: about a 70 or 75 on the 100-point scale (Tables 1 and 2). In both studies a standard deviation of around 25 suggests a wide diversity of feelings towards the police among the respondents.

Contact with the police. Each survey attempts to capture experiences with the police, though they use slightly different methods and questions to do so. Notably, these measures capture whether the respondent has had these kinds of contacts and not the quality of that contact (although the Appendix explores the question of explicitly negative experiences). In the APS, respondents were asked whether they were stopped or questioned by a police officer, whether they had family members stopped or questioned, and whether they had spent a night in jail or prison. The sample was randomly divided with half of the respondents being asked whether this contact had occurred in the last twelve months and the other half being asked if this kind of contact had ever occurred. Given this, we treat these two groups as separate samples, and report analyses separately. Not surprisingly, many more respondents reported they had ever had personal or vicarious contact with the police (more than half in both cases) than did those reporting on the last year (around twenty percent for each). Similarly, only two percent had spent a night in jail or prison in the past year relative to seventeen percent ever (Table 1).

In the ATS, all the respondents were asked the same questions. In a single question, respondents were asked if they or any of their family members had been stopped or questioned by a police officer in the last twelve months—a combined measure of personal and vicarious contact. Roughly a quarter of respondents said yes (Table 2). A second question asks whether the respondent has ever been arrested (a potentially less severe kind of contact than spending a night in jail or prison). Roughly a fifth of respondents said yes (Table 2).

Politics. To capture political ideology, two standard measures were employed in each study: identification as more liberal or conservative and identification as more Democrat or Republican, each on seven-point scales. The average respondent rated themselves roughly in the middle of both scales (Tables 1 and 2).

Racial attitudes. We explore three different kinds of racial attitudes. The first are violent crime stereotypes. In the APS, respondents were asked to rate “how well does the word “violent” describe most members from this group?” on a five-point scale from “not well at all” to “extremely well” separately asking about “Blacks” and “Whites.” The resulting measure is the difference between these ratings, reflecting how much better they thought violence characterized Black relative to White people. In the ATS, respondents were asked where they would rate “Whites” and “Blacks,” respectively, on seven-point scales from peaceful to violent. Once again, the former was subtracted from the latter. The small positive means for both indicate that the average respondent would rate them relatively equally, while leaning towards Black people being more violent (Tables 1 and 2). The standard deviations, however, suggest there is substantial variability in these ratings across respondents.

In both studies, racial affect is captured using thermometer scales on which respondents are asked to rate their feelings, separately, towards “Blacks” and “Whites” on scales from 0-100. We take the difference between the two creating a measure reflecting how much more coldly the respondent ranks “Blacks” relative to “Whites.” The average respondent in both studies rates Black people about three to five points more coldly than White people, though in both cases there is substantial variation in these opinions (Tables 1 and 2).

Finally, we also include a measure of racial resentment, a dimension of symbolic racism widely used in prior work (Henry and Sears, Reference Henry and Sears2002; Sears Reference Sears, Katz and Taylor1988). In both studies, we measure this as the average response (on five-point agreement scales) to four questions: whether Blacks should overcome prejudice and work their way up without “special favors,” whether slavery and discrimination created conditions that remained significant barriers for lower-class Blacks, whether Blacks had gotten less than they deserved, and whether inequalities would be solved if Blacks tried harder. The second and third questions are reverse-coded such that high values of the measure reflect greater racial resentment: the rejection of structural explanations for racial inequalities, the embrace of individualistic explanations, and a resentment of perceived line-cutting (e.g., Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2018; Henry and Sears, Reference Henry and Sears2002; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016).Footnote 8 A value above three in each of the studies reflects an average answer to the questions somewhere between “neither agree nor disagree” and “somewhat agree” for each of the questions—in other words, the average respondent is a little racially resentful of Black Americans (Tables 1 and 2).

Demographic and biographical controls. Our central interest is what mediates the effect of race. Both samples are restricted to non-Hispanic Black and White respondents, and we add a measure to distinguish between the two—roughly fifteen percent of respondents in each identified as Black or African American.Footnote 9 Both studies include a similar set of controls for alternative explanations that may be associated with basic demographic or biographical characteristics, including sex, age, marital status (those who are married or cohabitating and those who are separated, divorced or widowed, with single people as the reference category), years of education, and income (in $1Ks coded from category midpoints).

Methodology

All the outcomes are treated as continuous in linear models. In three of the four cases this is the obvious choice. In both surveys feelings toward the police are rated on a 101-point scale. In the APS, police discrimination is captured from an average of three standardized variables, each having seven or eight categories. In the ATS, police discrimination is captured on a seven-point agreement scale. As such, we also ran all the models treating this outcome as ordinal. The results were substantively identical to models treating the outcome as continuous, and as such the latter models are presented for ease of interpretation relative to the three other outcomes.

The two studies differ in the degree of missing data. As Table 1 illustrates, the APS has very little missing data—no variable was missing more than six cases, and altogether only seventeen cases had any missing data. Given the very small number, we simply drop these cases and present analyses based on the remaining full cases, though replacing the missing values via multiple imputation produced substantively identical results. The ATS involved more missing data across a variety of questions, although even here it was not severe: less than four percent were missing income; age and violent stereotypes were missing less than three percent; and all other variables were under two percent missing. Despite this, we employed a multiple imputation strategy (Allison Reference Allison2002) which does not depend on the assumption that data are missing completely at random, rather that the data are missing at random after controlling for other variables in the analysis. To this end, twenty data sets were imputed in a process that used all the variables from the analyses as well as several auxiliary variables to add information and increase efficiency using the mice package in R (R Core Team, 2019; van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, Reference van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn2011). This includes information on employment, stock market investment, and length of time in the neighborhood. Listwise-deleted results were substantively identical to those reported here.

Although the ATS involves two waves, the key questions involving views about the police, police contact, and racial attitudes were all asked only in the second wave, meaning both analyses are effectively cross-sectional. We have reasons to believe our assumptions about temporal ordering are reasonable. The police contact questions refer to past experiences, and prior research suggests in general that abstract political and racial beliefs and affect may be formed earlier and may inform later more specific attitudes (Peffley and Hurwitz, Reference Peffley and Hurwitz1985). However, we do recommend future confirmatory work that can better establish temporal ordering through a longitudinal design or causation through an experimental design.

To explore the meaning of our results and aid in interpretation, we ran a variety of additional exploratory analyses—for instance, interactions considering differences in the effect of police contact by race, or models which step in stereotypes and racial affect before racial resentment. Where relevant we mention these findings in footnotes in the results section, though none of these are critical to our key questions or findings.

Finally, our core question involves mediation. We estimate average mediation effects, bootstrapping 1000 samples (and including all the controls in models predicting the mediators) using the ‘mediation’ package in R (Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2011; Tingley et al., Reference Tingley, Yamamoto, Hirose, Keele and Imai2014). Mediation effects are estimates of the indirect effect, and an examination of the confidence intervals is analogous to examining the significance of an indirect effect in a structural equation modeling framework. Based on this analysis, we present figures describing estimates and confidence intervals for the average mediation effects and the proportion mediated (of the total effect—direct effects can be observed in the model).

Results

We are interested in factors that explain views about the police—and in particular that explain racial differences in these views. We investigate these questions in two different surveys, which are presented below in separate sections. Within each, we begin with basic models exploring the relationship of race, police contact, political identification, and racial attitudes with views about the police. Following up on this, we present tests of mediation for factors identified as potentially explaining racial differences in these views.

2016 ANES Pilots Study

APS respondents were randomly assigned to different versions of the criminal justice contact questions—half being asked only about contact in the past twelve months and the other half being asked about contact ever. We present the results here treating each as a separate sample.Footnote 10

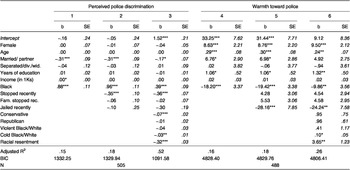

Sample with recent contact questions. We begin with the sample of those asked only about criminal justice contact in the last twelve months. Controlling just for basic demographic and biographical characteristics, there are large differences between Black and White respondents, on average, in beliefs about police discrimination and in overall feelings toward the police. Black respondents were on average nearly a standard deviation above White respondents in their belief that the police were more likely mistreat or discriminate against Black relative to White Americans (Table 3, Column 1).Footnote 11 Similarly, the average White respondent rated the police more than eighteen points higher on the 100-point thermometer scale than the average Black respondent (Table 3, Column 4).

Table 3. Coefficients from models predicting views of police from “last 12 months” sample of the APS

* p<.05; ** p<.01; ***p<.001.

Respondents who had recently been stopped were less likely to believe that the police operate with a racial bias against Black Americans (Table 3, column 2).Footnote 12 On the other hand, those who had recently spent a night in jail were less likely to view the police favorably (Table 3, column 5). However, the adjusted r-squares and BICs suggest that contact with the police or criminal justice system add very little to the explanation of views about the police,Footnote 13 nor do they appear to explain much of the direct effect of race—for which the coefficient appears to increase slightly in both models.

Those who identify as conservative were less likely to believe that the police act in biased ways towards Black Americans (Table 3, column 3). Those who possess anti-Black animus—those who rated “Blacks” more coldly than “Whites”—were less likely to believe the police act in discriminatory ways toward Black Americans and were more likely to feel warmly toward the police overall (Table 3 columns 3 and 6). Those who felt racially resentful of Black Americans were substantially less likely to view the police as biased and felt substantially more warmly toward the police overall.Footnote 14 Collectively, these factors add substantially to the overall explanation of views about the police as reflected in the big increases in the adjusted r-squares and the large drops in the BICs. They also appear to explain some of the racial differences in these views: the coefficients for race are much lower in these models, though in both cases still significant.

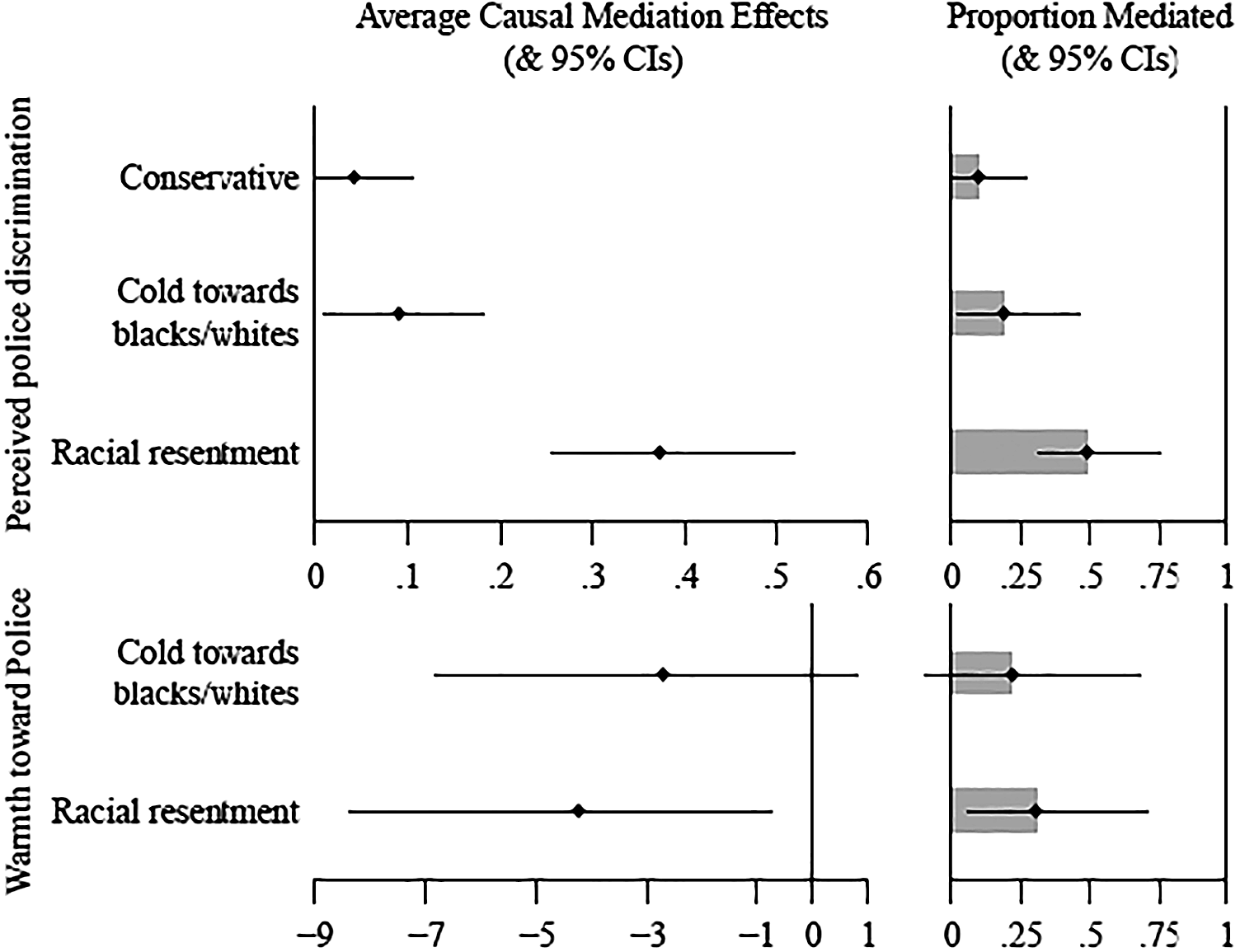

We explore whether any of these factors explain racial differences more directly by examining average mediation effects and the proportion mediated (see Imai et al., Reference Imai, Keele, Tingley and Yamamoto2011). We do this for any potential mediator outlined in the front end of the paper which appear based on the analysis to be likely candidates for mediation: any of the measures of criminal justice contact and political or racial views that are racially stratified and are significantly associated with the outcome in the appropriate direction.Footnote 15 Figure 1 presents estimates and ninety-five percent confidence intervals (based on 1000 simulations) for the average mediation effect (the indirect effect) as well as the proportion mediated. The mediation (or indirect) effects are presented on the left side and the proportion mediated on the right. Conservative identification has a small and non-significant (the confidence interval crosses zero) average mediation effect on beliefs about police discrimination. In other words, despite the fact that White Americans are more likely to identify as conservative and the fact that those who identify as conservative are less likely to believe in police discrimination, identification as a conservative does not explain why White Americans are less likely to believe in police discrimination. This is the equivalent of finding a non-significant indirect effect in a structural equation modeling approach to testing mediation.Footnote 16 Racial animus has a modest and significant average mediation effect on views of police discrimination, explaining roughly a fifth of the total effect of race. Racial resentment has an even larger and significant average mediation effect, explaining nearly half of the total effect of race on beliefs about police discrimination. For affective support for the police only racial resentment has a significant average mediation effect, explaining about thirty percent of the total effect of race.

Fig. 1. Selected results from tests for mediation from “last 12 months” sample of the APS

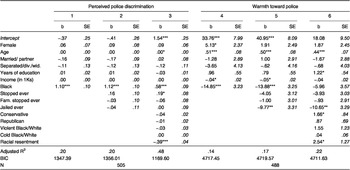

Sample with ever contact questions. We turn to the other sample from this survey: those who were asked whether they ever had criminal justice contact. Once again, there are large racial differences, with Black respondents substantially more likely to believe the police act in discriminatory ways—on average more than a standard deviation above White respondents—as well as rating the police substantially lower (about fifteen points) on the thermometer scale (Table 4 columns 1 and 4).

Table 4. Coefficients from models predicting views of police from “ever” sample of the APS

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

The experience of ever being stopped—in person or vicariously—does not seem to matter to views about the police (Table 4 columns 2 and 5).Footnote 17 Those who have ever spent a night in prison or jail are less likely to feel warmly toward the police, rating them on average ten points lower than those who never had this experience. However, as in the other half of the sample, adding these measures of criminal justice contact does not seem to improve the fit of the model overall much—in fact, BICs increase for both outcomes. Similarly, the inclusion of contact collectively does not appear to explain much of the direct effect of race.

For perceptions of police discrimination, the only political or racial attitude that appears relevant is racial resentment, which does appear strongly related (Table 4 column 3).Footnote 18 The direct effect of race appears diminished in this model, though remains significant.Footnote 19 Respondents identifying as more conservative were more likely to feel fondly toward the police overall, as were those who possessed racial resentment toward Black respondents—both of these effects, however, were modest (Table 4 column 6). Notably, in this final model the direct effect of race has dropped below conventional levels of statistical significance.

As above, we also directly examine whether these factors mediate the effect of race.Footnote 20 Figure 2 presents average mediation (or indirect) effects on the left and the average proportion mediated on the right, each with confidence intervals based on 1000 simulations. As in the other half of the sample, racial resentment appears to be a powerful mediator of racial differences in view of police discrimination, explaining about half of the differences overall. Racial resentment is also estimated to explain about a third of the racial differences in positive feelings toward the police, but neither this—nor any of the other potential mediators—significantly mediate the effect of race (the confidence intervals for each include zero).

Fig. 2. Selected results from tests for mediation from “ever” sample of the APS

2016 ANES Time Series Study

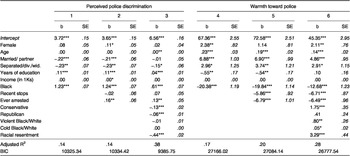

Finally, we repeat these analyses with data from our second survey. Consistent with the first survey, there are large racial differences in views about the police. Black respondents were nearly a standard deviation more likely to believe that police officers treat White Americans better than Black Americans (Table 5, column 1) and rated the police about twenty points more coldly on the 100-point thermometer scale (Table 5, column 4).

Table 5. Coefficients from models predicting views of police from the ATS

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001. N=2974.

Those who have ever been arrested were more likely to believe that the police treat Black Americans worse than White Americans (Table 5, column 2).Footnote 21 Both the experience of a recent police stop and an arrest ever decreased affection for the police (table 5, column 5).Footnote 22 For perceptions of police discrimination, adding contact does not appear to improve the fit of the model overall, however these factors do collectively appear to modestly improve the model explaining people’s feelings about the police—from about seventeen to twenty percent of the adjusted variance explained and a small decrease in the BIC. The direct effect of race, however, appears to change very little in these models.

Those who identify as conservative or as Republican were less likely to believe that the police treat Black Americans worse, and conservative respondents rated the police significantly more warmly (Table 5, columns 3 and 6).Footnote 23 Those who believe Black people are generally more violent than White people felt more warmly toward the police overall, as did those respondents who reported feeling less warmly to Black people relative to White people overall.Footnote 24 Those who are racially resentful of Black Americans are less likely to believe that the police are more likely to mistreat Black Americans and more likely to feel warmly toward them overall. Collectively, these factors appear to substantially improve the fit of both models, and in both cases the direct effect of race appears smaller, suggesting these factors may be explaining some of the difference in average views about the police between White and Black Americans.

We also directly explore mediation.Footnote 25 Figure 3 presents estimates and ninety-five percent confidence intervals for average mediation effects (on the left) and the proportion mediated (on the right) for each candidate. Racial differences in political ideologies appear to significantly explain some of the racial differences in view of police discrimination, with conservative identification mediating approximately eight percent of the total effect and Republican identification mediating about seventeen percent. Racial resentment plays an even larger role, explaining more than forty percent of the total racial differences.

Fig. 3. Selected results from tests for mediation from the ATS

For feelings toward the police, a variety of factors appear to play some role. The experience of police stops plays a small role, mediating around four percent of the total effect. Conservative identification mediates around five percent. Neither violent stereotypes about nor a relative coldness toward Black Americans significantly mediates the role of race (the confidence intervals for each include zero). However, once again racial resentment appears to be the most important factor, explaining more than a fifth of the total effect.

Discussion

Summary of Key Findings

Our interest here is in what explains people’s views about the police, and specifically what explains differences in how Black versus White Americans view the police. To answer this question, we employ data from two different national surveys, each including two different dimensions of how people view the police as well as a variety of measures of contact with the police, political and ideological identification, and racial attitudes and feelings. The product of this work is six sets of models and mediation analyses, allowing us to explore factors that are connected to views about the police across the samples, measures, and models. Several important findings emerge.

First, race itself is one of the most striking predictors of views about the police. In each of the surveys, White respondents rated their belief that the police mistreat Black citizens more than White citizens about a standard deviation lower than Black respondents. Similarly, White respondents rated the police, on average, about twenty degrees warmer on the 100-point feelings thermometer than the average Black respondent.

Second, contact with the police was related to views about the police, with the kind of contact that mattered differing across the studies.Footnote 26 The experience of a recent stop made people less likely to believe the police were discriminatory and feel more coldly toward the police in some of the samples. Any kind of experience with arrest or imprisonment made people less likely to feel warmly toward the police overall. However, these experiences with the police did little to explain differences between Black and White respondents in their views about the police (based on the mediation analyses), nor did they add much to the explanation of views about the police overall (based on overall model fit).

Third, political identification was related to views about the police in some of the models. Those who identified as conservative were less likely believe the police to be discriminatory in two of the three models, and Republicans were less likely to believe this in one of the three. Those who identified as conservative were also more likely to feel warmly toward the police in two of the three models.

Fourth, racial affect and violent crime stereotypes were also relevant to views of the police in some of the models. Those who felt more coldly toward ‘Blacks’ versus ‘Whites’ were less likely to believe in police discrimination in one of the three models, and more likely to rate the police warmly in two of the three samples. Stereotypes of Black Americans as violent were associated only with warmer views about the police in one of the three samples. Notably, however, these stereotypes were significantly related to a diminished belief in police bias and more affection for the police in all three samples when the measure of racial resentment is omitted.

Fifth, and finally, one predictor seemed to stand apart in the analyses: racial resentment was associated with a lower likelihood of believing the police to be discriminatory and a generally warmer feelings toward the police in all the samples. Racial resentment also significantly mediated the effect of race in five of the six models, often explaining a substantial portion of the variation: nearly half of the differences in views of police discrimination and twenty to thirty percent of the differences in warmth toward the police.

The seemingly less important roles for racial crime stereotypes and racial animus relative to racial resentment have important implications. As we suggest above, if stereotypes alone were associated with views about the police, it could be the role of stigma, rooted in ignorance. A role for racial affinity alone might also be rooted in the ignorance produced by a lack of contact with Black Americans. Instead, however, it appears that both may serve in part as proxies for racial resentment. This is consistent with the view that prejudicial attitudes and racial animus are the product of and justification for more basic concerns about racial group positions (Blumer Reference Blumer1958; Kendi Reference Kendi2017).

In sum, then, we find, consistent with prior work, large differences, on average, in views of the police between Black and White Americans. We also find that experiences with the police play a role in these views, though not one that does much to explain the racial gap in views of the police—though it may be that specifically negative experiences with the police would explain more of this racial gap. Instead, we identify a racial resentment of Black Americans as a particular important influence on these views overall and a particular important explanation for average racial differences in these views. This racial resentment, consistently higher among White respondents, appeared to explain a substantial portion of the racial differences in views about the police between Black and White respondents. Thus, views about the police are primarily shaped by views of race, specifically views which minimize historical and contemporary discrimination and are rooted in a resentment of perceived efforts to upset the racial status quo.

Conclusion

This work has important implications for a variety of fields and lines of research. Research on how the public views crime and justice issues has often focused on experiential factors such as victimization or encounters with law enforcement, while giving less consideration to the racial politics of these issues (with some notable exceptions, e.g., Callanan and Rosenberger, Reference Callanan and Rosenberger2011; Matsueda and Drakulich, Reference Matsueda and Drakulich2009; Peffley and Hurwitz, Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010). Yet crime and justice issues have long held important symbolic and political meaning (e.g., Beckett and Sasson, Reference Beckett and Sasson2004; Tonry Reference Tonry2011). This is especially important when crime and justice issues have pressing social and political relevance, as they did for example during the ‘long hot summers’ of the late 1960s, in the aftermath of the Rodney King case in the 1990s, and during the Black Lives Matter movement beginning in the 2010s. Thus, researchers need to understand these views not as clinical evaluations, but as symbolic positions connected to racial and political views.

Second, and relatedly, research should problematize rather than valorize the generally high levels of support for the police among White Americans. A substantial volume of research details racial bias and the disproportionate mistreatment of Black Americans by the police. Until that changes, concerns about police bias and something well short of full support for the police are warranted and appropriate. Failures to acknowledge this bias, and strong expressions of support for the police when this bias in mistreatment persists should be acknowledged as problematic, rather than lauded as the goal. This is especially the case among White Americans, for whom these views are disproportionately rooted in racial animus towards and a resentment of Black Americans.

This has particularly important implications for two specific dimensions of some work on procedural justice and legitimacy. This paper does not test, nor are we challenging any of the key findings of this perspective. Instead, we are raising questions about two aspects present in some of this work: a focus on explaining the on average more negative views about the police among Black Americans rather than the on average more positive views of White Americans, and, relatedly, the assumption that positive views of the police—and the obedience to the police they deliver—should be the goal.

First, the procedural justice literature has often framed the racial gap in views about the police as what Monica C. Bell (Reference Bell2017, p. 2058) describes as a “legitimacy deficit.” In doing so, this work implies that the more negative views of the police among many people of color is the problem to be addressed, while the substantially more positive average views about the police among White Americans are the goal. This is not to say that we should not be concerned with how the police treat people of color. Beyond the obvious violation of a constitutionally mandated equal protection under the law, a voluminous literature described above speaks to the harms caused by the disproportionate mistreatment of Black Americans. Rather, we suggest a shift in the question we ask about this racial gap, one in which concerns about police biases and something short of full-throated support of the police should be the goal for all Americans, at least while the police continue to disproportionately mistreat Black Americans. In short, the question should not be why Black Americans have, on average, more negative views about the police but why White Americans, on average, have such positive views. Critically, this simple shift places greater emphasis on racial and political factors.

This reframing is particularly important given the end goal of police legitimacy and procedural justice work: to convince citizens to obey both the law and the police (e.g., Tyler Reference Tyler2006). As Bell (Reference Bell2017) notes, racial disparities in procedural justice capture an incomplete portrait of the broader problem, in which many Black Americans also experience vicarious marginalization—a consequence of police mistreatment specifically targeting Black Americans—as well as structural exclusion. People can see the police as legitimate, comply with police orders, and still feel estranged from the legal system and the broader society (Bell Reference Bell2017). Procedural justice is hollow when substantive and structural injustices remain intact, and in this light the goal of securing compliance with an unjust system is perverse and problematic.

Bell (Reference Bell2017) suggests a reorientation away from procedural justice and cooperation and towards procedural and structural routes to social inclusion. Our findings support this call by suggesting that those who support the police and view them as unbiased do so when motivated by exclusion—in particular a dislike of and concern about the threat that efforts to better include and elevate Black Americans poses to the social and economic standing of White Americans.

This is important because procedural justice is frequently named as a primary method to achieve racial justice in response to complaints about inequalities and biases. For example, the final report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing—commissioned in the wake of mass protests over the shooting detail of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri—made legitimacy “Pillar 1” of its recommendations. Ibram X. Kendi (Reference Kendi2017) distinguishes segregationist, assimilationist, and anti-racist approaches to issues with racial dimensions. Older models of policing that explicitly recommend differential policing for Black Americans are clearly segregationist approaches (e.g., Westley Reference Westley1953; see discussion in Bell Reference Bell2017). In the most generous light, procedural justice may appear to be anti-racist when it focuses on changing the police treatment of Black Americans. But in attempting to affect change in the behavior of Black Americans with the goal of securing respect and cooperation with a system under which they remain unequal and estranged, the perspective may be better understood as assimilationist. In light of our finding that the generally more positive views about the police—including fewer beliefs that the police engage in racial bias—found among White Americans are explained in part by their animus and resentment of Black Americans, setting these views as the goal for Black Americans seems especially problematic. Instead, truly anti-racist approaches would focus on inclusion and explicitly problematize views about the police rooted in exclusionary motivations.

We conclude with a reminder of the stakes. Many Black Americans experience a legal estrangement from the police, the justice system, and society more broadly (e.g., Bell Reference Bell2017). Many Black Americans lack faith and confidence in the police, a consequence of what they know about the disproportionate mistreatment of Black Americans by the police. This matters: the police are public servants tasked with public safety, and yet when the safety of Black Americans is threatened, many do not feel able to call on this public service. Worse still, the police themselves can present a threat to the safety of Black Americans. When the police become symbolic tools for racist political discourse (e.g., Drakulich et al., Reference Drakulich, Wozniak, Hagan and Johnson2020), and when the police are used to confront and suppress protests about police racial bias, Black Americans experience more estrangement. When, in the midst of calls to recognize this police bias, many White Americans deny the bias and express support for the police—and do so out of an animus toward Black Americans and a desire to preserve racial inequalities—Black Americans experience even more estrangement and marginalization.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X22000133.