Over the past 6 years, the humanitarian system has undergone a series of major reforms in an attempt to address inadequacies that have hindered effective response( Reference Adinolfi, Bassiouni and Lauritzsen 1 ). Climate change, ongoing conflict and global economic recession are all contributing to the increasing frequency of humanitarian emergencies worldwide( 2 ). The need to strengthen the system to manage and respond to these crises remains a priority. A key aspect of the humanitarian reform process has involved developing capacity. The 2005 Humanitarian Response Review noted: ‘there are simply not enough people with the right experience available quickly’( Reference Adinolfi, Bassiouni and Lauritzsen 1 ). In response, there has been increased investment in training and professional development for existing and future cadres of humanitarian staff.

As part of this process, a number of international organisations have debated the value of professionalising the humanitarian sector( Reference Walker and Russ 3 ). It has been argued that a recognised set of standards for humanitarian staff would improve performance and promote quality and accountability( Reference Walker, Hein and Russ 4 ). The result has been the development of a number of competency frameworks, which are increasingly being used to measure ability and to structure training. The concept of competencies emerged during the early 1980s as a response to the need for improved performance in the business sector. Competencies are defined as the behaviours and technical attributes that individuals must have, or acquire, to perform effectively in a particular role( 5 ). The benefits of adopting competency-based training and development in the humanitarian sector were described by People in Aid: ‘competency frameworks provide a potentially powerful way of better ensuring that recruitment choices and the development of people fits the roles they will fill. The hope is that by making clear the ways people are expected to behave and in which they will be held to account for their behaviours, individual performance will improve, followed by increased team and organisational effectiveness’( Reference Swords 6 ).

To date, members of the Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies have agreed a core humanitarian competency framework( 7 ) and several ‘technical’ competency frameworks have also been produced for different sectors( 8 , 9 ). The core competencies are considered to be the foundation set of skills for effective national and international humanitarian staff, with the technical competency frameworks providing benchmarks for ability and performance in specialist areas.

Outside the immediate humanitarian domain, several livelihoods, nutrition, dietetics and public health technical competency frameworks have been recently developed or are in the process of development( Reference Ash, Dowding and Phillips 10 – Reference Schofield, Ashworth and Annan 15 ). Work is also ongoing that could, in time, allow for the international professional recognition of public health nutritionists( Reference Davies and Hughes R & Margetts 16 ). The importance of workforce development for the successful implementation of nutrition policy objectives, in both high- and low-income countries, is being increasingly recognised( Reference Yngve, Tseng and Haapala 17 , Reference Pelletier, Frongillo and Gervais 18 ).

However, no technical competency framework had been developed to describe the skills required for emergency nutrition preparedness, response and recovery; a sector within the humanitarian system that is experiencing serious gaps in capacity, having faced a notable lack of skilled staff for many years( Reference Gostelow 19 ). Emergencies put affected populations at a much higher risk of malnutrition and disease. In order to prevent malnutrition in these contexts, and to treat cases that do arise, a cadre of nutritionists are needed at both national and international level who can respond quickly and effectively to emergencies. The recent establishment of the Nutrition in Emergencies Regional Training Initiative, which is intended to provide sustainable, high-quality training in nutrition in emergencies (NIE), highlighted the need for a more detailed examination of the role of emergency nutritionists and the skills required( 20 ).

The competencies required of a nutritionist working in emergencies differ between agencies and contexts, and the content of training courses varies significantly. In an attempt to develop a technical competency framework for NIE that is both globally applicable and also addresses the diversity of operational requirements, we worked with key stakeholders in the sector. In the present paper we document the process of developing the proposed framework and discuss some of the potential opportunities and challenges to its implementation as a tool to strengthen human resource capacity.

Methods

Review of existing literature on humanitarian competencies

A review of the literature relating to humanitarian competency frameworks was undertaken using the PubMed and Web of Knowledge electronic databases. A search was also conducted in the resources section of the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC) website( 21 ) and requests for information and existing frameworks were sent to operational agencies.

Interviews were conducted with senior staff from two sectors that have implemented a competency-based approach for training and assessment (Humanitarian Logistics and Child Protection in Emergencies (CPIE)). Interviewees were purposefully chosen for their involvement in the development and regular use of the frameworks. Additional frameworks were collated from humanitarian organisations and reviewed. The structure for the NIE framework was then chosen based on the merits and uses of the existing frameworks. This process was also used to ascertain how the NIE competency framework could be used as part of recruitment, assessment and training.

Construction of the competency framework

The key features of a competency framework were identified from the review of existing frameworks (see Table 1) and, using these as a guide, the NIE competencies identified were categorised as either technical or core. Core professional competencies are regarded as those that are needed to function effectively in a work environment and include behaviours such as the ability to communicate and work effectively with others, while core humanitarian competencies include behaviours that are required for humanitarian work, such as the application of humanitarian principles. Competencies that already feature in the existing core humanitarian frameworks were removed to avoid replication. The competencies were then assigned to a technical domain and, where necessary, re-formulated into a behavioural indicator. Expressing competencies in the form of behavioural indicators facilitates the use of a framework as a tool for assessing ability and performance. This was done using a revised version of Bloom's taxonomy of learning behaviour as a guide( 22 ). Each behavioural indicator was then allocated to one of three levels, corresponding to progressive seniority within the sector (see Table 2). This allocation was done using NIE job specifications for posts requiring varying levels of professional experience.

Table 1 Competency frameworks in related sectors

Table 2 Proposed structure for nutrition in emergencies competency framework

Identification of nutrition in emergencies competencies

The identification of NIE competencies was designed to be as comprehensive as possible, and consisted of four stages. First, existing competency frameworks, course curricula and emergency nutrition job specifications were reviewed and relevant competencies extracted. Frameworks, courses and job specifications were included only if they featured an aspect of emergency nutrition.

Second, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a convenience sample of ‘field experts’ working for humanitarian organisations. The sample consisted of three independent consultants, three employees from UN agencies and three employees from international non-governmental organisations (NGO). The interview questions were designed to explore which competencies were viewed as essential for an emergency nutritionist and also those that interviewees perceived to be commonly limiting in the field. Where necessary, questions were open-ended to encourage interviewees to expand on the issue. Interviews were conducted by telephone due to the geographical spread of participants and lasted approximately 45 min.

Third, participants from NIE courses held in Uganda, Thailand and Lebanon in 2010 and 2011 were contacted to identify which skills they felt were essential for their roles in emergency nutrition( 20 ). Finally, the compiled list of competencies was reviewed by members of the Capacity Development Working Group of the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC-CDWG) during the second half of 2011.

Results

Existing humanitarian competency frameworks

Six humanitarian competency frameworks were identified and reviewed (see Table 1). Interviews were then conducted with two key informants from the Humanitarian Logistics and CPIE clusters.

From these interviews, and the review of the frameworks, three key features were identified. (i) Competencies were categorised as either core or technical, with a number of frameworks focusing exclusively on core competencies and others on both core and technical. (ii) All the frameworks reviewed organise the competencies into domains. Within these domains, most frameworks then outline specific behaviours or examples of how to successfully demonstrate skills relating to each domain. The Humanitarian Logistics framework includes key learning points within each domain to ensure complete coverage of required skills. (iii) Most of the frameworks have been further developed to take into account progressive levels of learning, with each level featuring a set of behavioural indicators.

Structure for the nutrition in emergencies framework

This review of the existing competency frameworks and their key features led to the proposed structure for the NIE framework shown in Table 2. The categorisation of competencies and assigned behavioural indicators with progressive additive levels provides clarity regarding the skills required and gives a clear vision of career progression. This structure is based closely on the CPIE framework.

The CPIE framework includes core humanitarian competencies which are based on those previously identified by the Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies. We recognise that these core competencies are essential for all humanitarian workers, and so the NIE framework is designed to be used in conjunction with these.

Extraction, compilation and selection of competencies

Seven courses that either focus on NIE or include relevant components were identified and included for review. Courses ranged from master's degree level, to short, non-accredited training.

A total of fifty-six NIE job specifications were identified with roles ranging from graduate entry level to those requiring over 10 years’ experience. Job titles included nutrition advisers, coordinators, programme managers and chiefs of health and nutrition. The hiring organisations consisted of international humanitarian NGO and UN agencies, with thirty-six and twenty job specifications, respectively.

Full interviews were conducted with eight NIE experts; a further two responded to selected questions by email. All the interviewees work in international emergency nutrition and have between 8 and 23 years’ experience working across Africa, Asia, Europe and America.

Feedback from twenty-five NIE training course participants in Thailand, Lebanon and Uganda was collected. Participants were staff working for governmental departments in health and nutrition and international NGO, and came from a wide range of countries in Asia, Africa and elsewhere. The participants were asked to list the skills they used for their roles in emergency nutrition and specifically those for which they felt they required more training.

Once collected, the competencies from each method were assigned to a domain (e.g. preparation of F-100, a therapeutic treatment for acute malnutrition, would be assigned to ‘management of acute malnutrition’). These competency domains are shown in Table 3. Examining the tables reveals that some domains which are identified as essential in job specifications and by key informants do not feature in the training course curricula. In general, the technical nutritional competencies are covered, with the main disparity in the more general competencies such as leadership, communication and policy development.

Table 3 Competency domains identified from course curricula, job specifications and key informant interviews (listed alphabetically)

NIE, nutrition in emergencies.

Filled circles indicate the inclusion of the competency domain.

To avoid duplication, any competencies which were already included within the CPIE core competency framework were extracted so the NIE framework contains only technical competencies. That is not to suggest that these core areas should be ignored; indeed, the NIE technical competency framework should be used alongside the existing core competency framework, ensuring all essential competencies are considered.

In terms of gaps in skills, the main theme that emerged from the interviews was management and leadership, which was mentioned by the majority of respondents. One interviewee stated: ‘Management and leadership skills are not usually taught, yet once staff reach a certain level they are expected to possess these skills, which is often not the case’.

Other limiting competencies mentioned include: understanding and adhering to guidelines, analysing data, report writing, training others, working well with different teams, strategy writing, coordination, adapting programmes to suit the specific context, communicating with media, funding applications, and knowing where to find resources. In addition, skills related to the integration of community management of acute malnutrition into health systems, prevention and treatment of malnutrition, and social and behavioural change were noted as lacking among NIE personnel.

The next step was to develop behavioural indicators for each competency within the technical domains that had been identified, using Bloom's taxonomy action verbs. Once these were developed the whole framework was reviewed by members of the GNC-CDWG and the framework was then revised based on their feedback. The full competency framework including behavioural indicators is shown in Table 4. The proposed framework contains twenty competency areas with 161 behavioural indicators categorised into three levels.

Table 4 Technical competency framework for nutrition in emergencies practitioners

GFD, general food distribution; IYCF-E, infant and young child feeding in emergencies; BCC, behavioural change communication; M&E, monitoring and evaluation; WASH, water, sanitation and hygiene; BSFP, blanket supplementary feeding programmes; CMAM, community-based management of acute malnutrition; OTP, outpatient treatment programme; TSFP, targeted supplementary feeding programme; SC, stabilisation centre; DRR, disaster risk reduction.

Application of the nutrition in emergencies competency framework

Across the sectors reviewed, competency frameworks are used as a basis for recruitment, development of training and for professional development. From the interviews with CPIE staff, a more detailed overview of the processes involved in applying a competency framework emerged.

Recruitment

The CPIE framework is used to create job profiles which define the key competencies required for a role and the necessary level of skill. Once a profile has been created it is used to form a job description and as a reference against which to assess candidate suitability. Recruitment assessment methods include scenario questions, observation, and role play in group assessments. This improves recruitment processes, ensuring that the selected individual has all the competencies essential for the role. Those with a lack of formal academic qualifications, such as a relevant BSc, MSc or professional training certificate, are not necessarily excluded in this process as the essence of a competency-based approach is that individuals are assessed on skills and attributes that may have been gained through experience or personal development.

Using the example of a Nutrition Coordinator, an example job profile was created using the NIE competency framework and is shown in Table 5.

Table 5 An example job profile for a Nutrition Coordinator

CMAM, community-based management of acute malnutrition.

Note: This example is purely illustrative, there may be additional competencies required for the role of a nutrition coordinator in different contexts.

Training

The framework can also be used as a reference from which training is developed with the indicators relating to learning objectives, thereby standardising training courses across the sector. Competency-based training naturally leads on to competency-based assessment methods. In studies on assessment methods from the medical sector, it has been shown that in addition to standard essay and exam questions, assessing technical and behavioural competencies through observation of simulated situations is a valid method( Reference Gaba, Howard and Flanagan 23 ). This approach facilitates the assessment of a person's behaviours such as decision-making capacity in addition to technical competencies.

Professional development

The framework can also be a tool for professional development and continuous learning. Staff can use the framework as a self-assessment tool, grading themselves for each competency and identifying areas which would benefit from further development. The competency areas in which they score lower, or areas which they would like to develop, can then be focused upon, with the behavioural indicators providing clear examples of what is required to attain each level.

Discussion

In the present paper we have proposed the structure and contents for a competency framework for practitioners in NIE and described how it could be used to improve staff recruitment, assessment and professional development. We have also extracted and synthesised competencies and developed behavioural indicators for each. The framework has since been adopted for preliminary use by the international NGO Concern Worldwide, World Vision, Valid International and International Medical Corps. This is an important initial step to developing a competency-based approach to human resource development for emergency nutrition practitioners, and the framework should provide a valuable tool for strengthening capacity within the sector.

The benefits of a competency-based approach have been increasingly studied and discussed, with the medical sector investing heavily in research in this area. The key benefits that have been recognised include the introduction of transparent standards and increased public accountability. The standardisation of training and provision of a clear framework also encourage learning and professional development( Reference Voorhees 24 ). In other humanitarian sectors it is felt that the introduction of a competency-based approach improves recruitment processes and is viewed as having been beneficial in developing capacity within the sector (K Bisaro, personal communication, 2011).

However, the approach is not without its criticisms and there are recognised limitations, including an increased administrative burden and possibility of a focus on achieving acceptable minimum standards rather than the best that is possible. Despite these limitations, competency-based learning is now dominant at most stages of medical training in high-income countries( Reference Leung 25 ).

Regardless of how comprehensive and well-constructed a framework is, its success is contingent on gaining widespread acceptance and ensuring effective implementation. A key lesson learned within the medical sector is that there needs to be a clear implementation strategy from the outset( Reference Leung 25 ). Through the present research, we have explored the three main ways in which the framework may be used – for recruitment, training and professional development – based on the approaches described within the CPIE competency framework( 8 ). However, further work is required to explore the specific methods for implementation and challenges faced. For the NIE framework to be successful, it is important that we continue to learn from other humanitarian sectors that have engaged in this process.

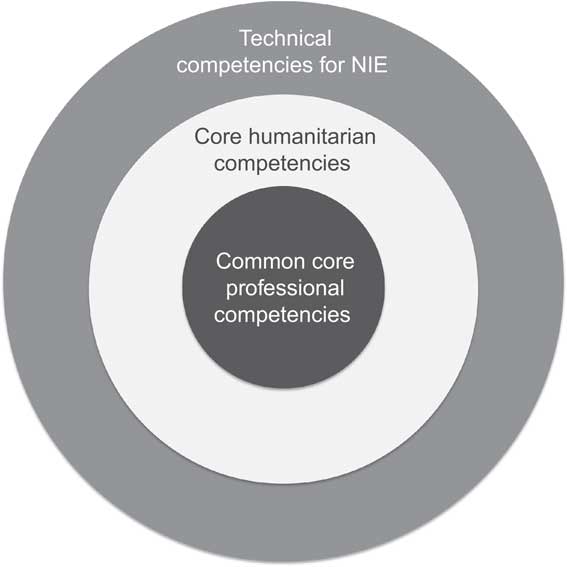

The competencies identified as essential for any individual working within NIE are diverse, encompassing common core competencies, such as communication and teamwork; humanitarian competencies essential to all humanitarian workers, such as knowledge and application of humanitarian system and standards; and nutrition specific technical areas, such as identification of micronutrient deficiencies. This leads to a layered approach to building a competency framework, which is based on the CPIE framework, and is shown in Fig. 1 ( 8 ).

Fig. 1 The layered approach to building core professional, core humanitarian and technical competencies for nutrition in emergencies (NIE)

When comparing the competencies identified in Table 3, we can see a clear difference between what was identified as essential from job specifications and interviews and what is currently being taught in the academic and training courses we reviewed that focused on NIE. While the majority of the technical skills are covered, the main difference lies in the more general competencies. This is further supported through the findings from the interviews, where many of the same competencies are regarded as limiting effectiveness in the field, with seven interviewed experts commenting on the lack of leadership and management training in particular.

It may seem obvious that general core competencies are an important part of any role, yet this research has found that many are sorely neglected when it comes to training and were noted as limiting effectiveness in the field. So, our findings are that not only is there a lack of national and international nutritionists who can be deployed in response to emergencies, but those who are available may lack some of the essential competencies required to perform effectively. This was evident in a self-assessment of general nutrition capacity in the twenty countries with the highest global burden of undernutrition, where the main weaknesses were found to be in the areas of management and training( Reference Bryce, Coitinho and Darnton-Hill 26 ).

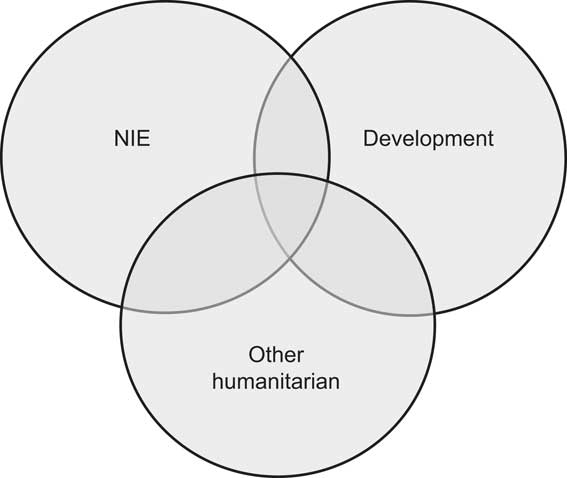

It has been noted that there are many important commonalities between development and emergency nutrition, and while developing the NIE framework it became apparent that many of the required competencies are not specific to emergency nutrition but overlap with disaster preparedness, recovery and long-term development work( Reference Gostelow 19 ). There is also strong overlap with other humanitarian sectors such as food security and logistics. For example, data collection and surveys is a competency area required by both emergency and non-emergency nutritionists; however, in an emergency there are additional specific skills and behaviours required relating to data collection that differ from those required in a non-emergency situation.

A similar overlap was also found by the developers of the child protection framework, which led them to separate the competencies into three areas: (i) core humanitarian; (ii) general child protection; and (iii) emergency-specific competencies( 8 ). This approach allows those who come from other professional backgrounds to identify the competencies they already possess that are included in the framework, thereby encouraging those in general nutrition or other sectors such as food security or livelihoods to undertake specific training to build those competencies required for working in emergency nutrition.

Many situations fluctuate in and out of crisis so that ‘development’ nutritionists who are running existing programmes are required to respond to an emergency. As highlighted by O'Dempsey and Munlow: ‘a lack of definition as to what constitutes a humanitarian emergency and the absence of rules of engagement of NGOs and donors further complicates the problem’( Reference O'Dempsey and Munslow 27 ).

This then begs the question of whether it is appropriate to develop a separate competency framework for NIE when the required skills are so clearly interlinked with development work (Fig. 2). While there is an undoubted need to strengthen nutrition capacity in both development and emergency contexts, nevertheless there is a set of skills and knowledge that is unique to emergencies. In addition, the mechanisms by which staff are recruited, assessed and supported usually differ between the development and emergency sectors.

Fig. 2 The overlap of competencies between nutrition in emergencies (NIE) and other sectors

Limitations

Although every effort has been made to identify all essential competencies, the list may not be exhaustive due to the various limitations of the present research. Some relevant documents may be held by agencies and not be in the public domain. It is also noted that the competencies highlighted through expert interviews are likely to have been biased towards each individual's area of expertise and reflect international rather than national perspectives. Ideally a larger sample of field experts and national staff would have been included, with experts also included from government departments, training institutions, donor organisations and other NGO (national and international).

Some competency areas have gaps due to a lack of available information and this may or may not reflect the actual need for expertise in these areas of work. Areas like social and behavioural change and emergency preparedness are often neglected within job specifications and course content, and this is reflected in the framework.

Conclusion

The move to a competency-based approach is a logical step to strengthen the NIE sector and build human resource capacity. However, the competency framework proposed here will require further review involving a wider range of stakeholders that includes beneficiary populations, in order to encourage sector-wide adoption and use. The competency approach has already been adopted by the logistics and child protection sectors and is perceived to be beneficial, although formal evaluations are still required. It is therefore essential that indicators for monitoring and evaluating the use of competency frameworks are defined in order to build an evidence base on their use not just within NIE, but within the humanitarian sector as a whole.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This work was partly funded by a grant from the US Agency for International Development/Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance. The Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Ethics: Ethical approval was not required for this study. Authors’ contributions: J.M. conducted the data collection and wrote the first draft. C.E., K.G., C.A. and A.W. reviewed and revised the competency framework. A.P., C.D. and A.S. supervised the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.