Introduction

COVID-19 meant a time of “infodemic” (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Fletcher, Newman, Brennen and Howard2020), marked by the high presence of hoaxes in the public sphere. The false information ranged from theories about the origin of the virus to critiques of the lockdown measures and the vaccines. In a context of social distancing, this content was shared mostly through social networks, which are an essential tool for political participation (Kahne & Bowyer, Reference Kahne and Bowyer2018). At the beginning, the public communications of governments faced an unknown virus, but later, COVID-19 vaccines became the central point of discussion. However, many citizens may undervalue the work of experts and scientists because they are an elite, not representing “the people.” This problem had already been observed with previous vaccination campaigns in Western Europe (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2019).

Social media is also used by elites and politicians to promote certain issue agendas and to influence audiences, which is a sort of network propaganda (Benkler et al., Reference Benkler, Faris and Roberts2018). The 2016 U.S. presidential election is seen as one of the most remarkable examples of the presence of propaganda on social media platforms. Both candidates, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, built emotional frames to encourage behaviors, adapting their messages to the logics of different platforms (Sahly et al., Reference Sahly, Shao and Kwon2019). Therefore, emotions are key to fostering audience engagement in the current digital political communication.

The importance of these networks in the political media landscape has led to a shifting media culture, in which journalism has a precarious position (Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Robinson and Lewis2022). In this framework, there was also a phenomenon of news avoidance to protect perceived well-being during the first months of the COVID-19 crisis (de Bruin et al., Reference de Bruin, de Haan, Vliegenthart, Kruikemeier and Boukes2021). Avoiding news and the proliferation of conspiracy beliefs about the pandemic triggered a disinformation scenario (Bertin et al., Reference Bertin, Nera and Delouvée2020). It should be noted that so-called social media fake news acts as a predictor of political attitude change (Gil de Zúñiga et al., Reference Gil de Zúñiga, González-González and Goyanes2022), which may have affected evaluations of the politicians in charge.

Some authors connect the propaganda on social media with the distrust of governments and the consequent decline of democracy as a political system (Ali & Gatiti, Reference Ali and Gatiti2020; Kreiss & McGregor, Reference Kreiss and McGregor2018). The lack of trust reinforces doubts about the vaccine. In this sense, the pandemic took place within a hybrid media ecology. Legacy media and politicians coexist in the digital sphere with a broad list of actors such as grassroot influencers, activists, bots, and fact-checkers (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017). Fact-checking is rising as a new approach to political journalism to fight disinformation (Graves, Reference Graves2016). Based on technological infrastructures, these initiatives verify fake news and offer truthful information with an effect on elites (Nyhan & Reifler, Reference Nyhan and Reifler2015). International organizations such as the United Nations have highlighted the need to enhance the detection of fake news on social media as it impacts endorsement cues for the vaccine (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Hancock and Markowitz2020).

Digital political communication fueled a highly polarized media system at the global level (Pérez-Curiel et al., Reference Pérez-Curiel, Rivas-de-Roca and Domínguez-García2022). It is striking that the people ask for a coordinated response to health crises (Tyson et al., Reference Tyson, Funk, Kennedy and Johnson2021), but the chaos of modern public communication makes it difficult to find only one voice. Bearing this background in mind, we analyze the communicative actions of heads of government and fact-checking organizations on tweets about the vaccination. Accordingly, we pose three research questions:

RQ1: How were the agendas of political leaders from different countries built during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign?

RQ2: What were the most important propaganda mechanisms by leader?

RQ3: What was the impact of propaganda on the verification practices of fact-checking initiatives?

Political leaders’ digital propaganda toward COVID-19 disinformation

The COVID-19 pandemic affected not only the economy and public health, but also the field of communication, since communicating health issues is a way of addressing them (Milani et al., Reference Milani, Weitkamp and Webb2020). Governments had to manage crisis communication to explain the benefits of social distancing and lockdowns. Then, vaccines became a hope to end the pandemic. Political sources were predominant in constructing pandemic news across the world, displaying their important mission (Mellado et al., Reference Mellado, Hallin, Cárcamo, Alfaro, Jackson, Humanes, Márquez-Ramírez, Mick, Mothes, Lin, Lee, Alfaro, Isbej and Ramos2021). One of the main difficulties of carrying out a successful public health campaign is a postmodern belief that questions the legitimacy of science (Hornsey et al., Reference Hornsey, Harris and Fielding2018). This is added to the political confrontation between countries, which is a part of storytelling that requires clear enemies within an online media system (Guo & Vargo, Reference Guo and Vargo2020). On this matter, agenda setting is shaped by both platforms and mainstream media (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2017), moving leaders to be present in these two spaces.

The development of a public communication campaign links to propaganda. This core concept is defined by Jowett and O’Donnell (Reference Jowett and O’Donnell2018) as a form of communication that seeks to achieve a response that furthers the aim of the propagandist, which is different from political persuasion. The latter is more interactive and tries to satisfy the needs of both actors. The central purpose of these concepts consists of encouraging a particular perception, employing tools such as emotional language or the selective presentation of facts.

Nowadays, most propaganda is spread through social media, where ideas such as communication, persuasion, and disinformation overlap. Although propaganda is often associated with manipulation or disinformation (false information with an intention), it can be categorized as a kind of public communication. The communications of governments have a clear social function for democracy, especially at a time of disrupted public spheres (Bennett & Pfetsch, Reference Bennett and Pfetsch2018). This has been crucial in recent crises because communication works as a tool between public institutions and citizens to reduce social uncertainty about a new situation (Sierra-Rodríguez, Reference Sierra Rodríguez2020). Regarding the pandemic, world political leaders increased the number of public appearances they made (Rivas-de-Roca et al., Reference Rivas-de-Roca, García-Gordillo and Rojas-Torrijos2021), but most did not have contingency plans adapted to this situation. Thus, leadership approval of the management of the pandemic moved from consensus to dissensus, although there was a rise in personalized political leadership (Van Aelst & Blumler, Reference Van Aelst and Blumler2022).

In current political communication, most politicians prefer to use spectacular messages on social media, based on propaganda mechanisms that target specific groups of society (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Hsu, Neiman, Kou, Bankston, Kim, Heinrich, Baragwanath and Raskutti2018). One problem is when this propaganda narrative resorts to fake news, considered news with noncontrasted headlines or large-scale hoaxes (Tandoc et al., Reference Tandoc, Lim and Ling2018). In such cases, propaganda seems to be part of a disinformation campaign. Some research points to a relationship between the reception of false information and those who believe that all vaccines are unnecessary (Hornsey et al., Reference Hornsey, Harris and Fielding2018).

Prior scholarship has typically described disinformation as one of the most outstanding communicative phenomena, being understood as the intentional dissemination of false information for spurious purposes (Chadwick & Stanyer, Reference Chadwick and Stanyer2022). The concept connects to misinformative content that boosts deception. By contrast, “misinformation” refers to incorrect information that is not deliberatively deceptive (Woolley & Howard, Reference Woolley and Howard2016).

Although these problems are worldwide and many Western countries or international institutions such as the European Union have been targeted by disinformation campaigns, the impact by country and the level of resilience to online disinformation depend on previous national factors. According to Humprecht et al. (Reference Humprecht, Esser and Van Aelst2020), in northern Europe, there is high resilience to online disinformation; meanwhile, the populations of southern European countries and the United States are more likely to believe those fallacies.

Misleading content that pursues political goals tends to focus on the statements of leaders, especially on Twitter, delving into the personalization of politics that characterizes the current journalism (Carlson, Reference Carlson2018). This fosters a distortion of the value of facts for democracy, which are less relevant in journalistic reporting compared with self-interested quotes (Müller & Sältzer, Reference Müller and Sältzer2020). These practices are a breeding ground for disinformation (Conroy et al., Reference Conroy, Rubin and Chen2015), undermining political knowledge and, therefore, elections, the prestige of democratic institutions (Lee & Xenos, Reference Lee and Xenos2019).

In this turbulent context, the role of vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic has been more important than ever before, demanding extensive public communication to manage the crisis. Governments had to diversify their communication strategies to cover not only legacy media (Barroso Simao et al., Reference Barroso Simao, Gouveia Rodrigues and Madeira2016) but also digital platforms to reach audiences without intermediation (Shearer & Mitchell, Reference Shearer and Mitchell2021). This requires a domain of new communicative codes and monitoring the flow of health hoaxes and fake news, which are usually visual news items (Bode & Vraga, Reference Bode and Vraga2018).

Specifically, Twitter has been one of the main topics of the literature on political communication. This social network adapts to the working of politics, having a lot of possibilities in terms of exchanging information or learning about the shaping of public debates such as vaccination (Milani et al., Reference Milani, Weitkamp and Webb2020). Despite this potential, the use of Twitter by political actors is mostly reduced to propaganda messages, including sometimes false information, since interactions with fake news are huge on this platform (Allcott et al., Reference Allcott, Gentzkow and Yu2019).

The role of fact-checking platforms in a changing media culture

As mentioned earlier, the proliferation of fake news on Twitter can turn this social network into a risky space for audiences, far from the mission of defeating the virus. Besides that, the personal influence of political leaders and information overload (Wardle, Reference Wardle2017) are factors to take into account in the institutional discourse facing the pandemic. Political leaders’ propaganda may not help fight disinformation on Twitter as this state propaganda sometimes resorts to scant truthful data. In this context, the traditional values of journalism, such as credibility or accountability, should be important to counteract the spread of false information.

In a period of crisis, the use of journalistic strategies to differentiate truths and lies is key. Likewise, the quality of this content is a way to detect disinformation (Palau-Sampio et al., Reference Palau-Sampio, Carratalá, Tarullo and Crisóstomo2022). In recent years, there has been a noteworthy emergence of fact-checking platforms that verify content shared on social media (Graves & Amazeen, Reference Graves, Amazeen and Nussbaum2019). These initiatives are devoted exclusively to verification, which until then was a task of journalism.

Between 2012 and 2017, there was a proliferation of fact-checkers as a result of new technologies (Vázquez-Herrero et al., Reference Vázquez-Herrero, Vizoso and López-García2019). Fact-checkers operate through a collaboration between data journalists and computer engineers (Ufarte-Ruiz et al., Reference Ufarte-Ruiz, Peralta-García and Murcia-Verdú2018). Although these websites are based on journalists’ conscience and self-regulation, their participation in internationally recognized programs assures their credibility. For instance, many of them in Europe are part of the task force of the European Commission to deal with disinformation (Bernal-Triviño & Clares Gavilán, Reference Bernal-Triviño and Clares-Gavilán2019).

Fact-checking services are usually classified into two groups based on their business model: those dependent on the media and those financed by volunteers or civil society entities (Esteban-Navarro et al., Reference Esteban-Navarro, Nogales-Bocio, García-Madurga and Morte-Nadal2021). However, there are also cases of mixed funding. Advertising, donations, and collaborations with traditional media are common, following a scheme that is managed by two or three individuals (Vázquez-Herrero et al., Reference Vázquez-Herrero, Vizoso and López-García2019). The regulation of these initiatives is attached to the media law of each country. Thus, national politicians define them as news media.

Regarding content, the fact-checking websites deny false information that appears both on social networks and in the legacy media. Specifically, statements by political actors or hoaxes are usually verified, many of which are identified by the user community (Ufarte-Ruiz et al., Reference Ufarte-Ruiz, Anzera and Murcia-Verdú2020). Added to these strategies is a continuous personalization of the content, which easily adapts to the needs of the market and the audience (Moreno-Gil et al., Reference Moreno-Gil, Ramon and Rodríguez-Martínez2021).

The literature highlights the increasing influence of fact-checkers in politics, at a time of accusations by some leaders toward traditional media (Van Duyn & Collier, Reference Van Duyn and Collier2019). Even so, the attention in the hybrid media system is also determined by other actors such algorithmic agents (bots). These bots tend to amplify controversial viewpoints (Duan et al., Reference Duan, Li, Lukito, Yang, Chen, Shah and Yang2022), as this kind of partisan content reaches larger audiences. Furthermore, journalists and fact-checkers draw on social media metrics to assess news value and worthiness (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Wells, Wang and Rohe2018).

What is verified is not only decided based on journalistic reasons, but also on digital platforms’ dynamics. This affects the potential contribution of fact-checking services to ameliorate the democratic roots of public communication. Nevertheless, their work is mostly based on the journalistic concept of truth (Graves, Reference Graves2016). As a consequence, the relationship of fact-checkers with politicians is marked by the characteristics of watchdog journalism, which seeks accountability of the ruling elite.

Methodology

This study aims to offer insightful evidence on the shaping of propaganda about COVID-19 vaccination on Twitter, focusing on the role of global political leaders, since they may work as social prescribers. Data from this research were collected using Twitonomy, a tool developed by Diginomy that keeps a record of every public tweet posted by an account. Twitonomy is commonly employed as it allows the collection of visual analytics on anyone’s tweets, retweets, and replies (Guijarro et al., Reference Guijarro, Santandreu Mascarell, Canós Darós, Díez Somavilla and Babiloni Griñón2018). The importance of assessing the comparability of Twitter data is underlined in the literature (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Duan and Yang2022), but we chose Twitonomy instead of the popular Twitter API because Twitonomy generates preprocessed data through customizable reports and visual analytics by account, using data on content, likes, and retweets to provide statistics. The presence of propaganda mechanisms was considered to be observed through the discourse of opinion leaders.

Our research design covered the Twitter accounts of heads of government, which were assessed as political leaders, and one well-known fact-checking project for each country. The choice of countries spanned different media and political cultures: the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain (Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Cornia and Nielsen2020). Furthermore, these nations also participated differently in the worldwide production of COVID-19 vaccines. The United States and the United Kingdom were vaccine producers, whereas France and Spain are the largest European Union countries in size, making a comparison between them of interest.

The accounts examined included the following:

-

• United States: Joe Biden (president), PolitiFact (fact-checking website)

-

• United Kingdom: Boris Johnson (prime minister), Full Fact (fact-checking website)

-

• France: Emmanuel Macron (president), Les Décodeurs (fact-checking website)

-

• Spain: Pedro Sánchez (prime minister), Maldita.es (fact-checking website)

The sample is composed of all tweets containing the words “pandemic” and “vaccines” (“pandemic AND vaccines”) published by the cited accounts, although the word “vaxx” has also been used as a synonym for vaccines. Different attempts used a broader list of keywords, including “Covid-19,” “COVID,” “coronavirus,” and “vaccination,” but the total data volume did not increase significantly. Although we acknowledge that people may use different variations to refer to the same topic, the selected keywords work relatively well in the three languages of the sample (English, French, and Spanish). In addition, these keywords are in line with previous literature (Duan et al., Reference Duan, Li, Lukito, Yang, Chen, Shah and Yang2022; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Chen, Yan, Lerman and Ferrara2020). This helps ensure the validity for a comparative study, but the data search strategy also has limitations as some words may acquire a particular relevance. Machine-learning-based classifiers are a solution to locate these problems that could be developed in future data collections.

Our search on specific words tries to provide patterns of digital conversation (Cuesta-Cambra et al., Reference Cuesta-Cambra, Martínez-Martínez and Niño-González2019). Own tweets and responses are included, but not retweets, as they could be less useful to know the leaders’ agenda. The data were captured for a five-month period (January–May 2021) in which vaccines became available for elderly people in the four countries. This time frame is relevant as the starting point of a large vaccination campaign. A manual content analysis was applied to the tweets (n = 2,800). The data were processed with IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 28.

As long as the coding was carried out manually by the authors, a pre-test was conducted on 10% of the sample (280 units). The levels were acceptable for the average of variables (α = 0.87) according to Krippendorff’s alpha values (Neuendorf, Reference Neuendorf2002). We used a type of content analysis that adapts to social media logic by dealing with many variables (Fernández Crespo, Reference Fernández Crespo, Cotarelo and Olmeda2014). Short messages are targeted as places where social debates are posted. It should be noted that the number of tweets differs by country (770 in the United States, 358 in the United Kingdom, 274 in France, and 248 in Spain), but we provide aggregated data here to make comparisons. To avoid the cherry-picking problem, two scholars from different backgrounds in communication studies were invited to monitor the study, reducing the bias by suggesting additional interpretations.

The discursive analysis is based on categories of political language, using a classification of logical fallacies (van Dijk, Reference van Dijk, Wodak and Meyer2015): appeal to authority, appeal to emotion, fallacy against the man, appeal to force, appeal to ignorance, attributions, tendentious claims, emphasis, stereotypes, false analogy, speaking through other sources, opinions as facts, selecting information, and use of labels (see Appendix A for details). We borrow this classification for discourse analysis and apply it to propaganda analysis.

Nevertheless, our research also deals with propaganda from an issue/game approach because of the relevance of this theory to understanding the framing between topics and strategies (Cartwright et al., Reference Cartwright, Stepanova and Xue2019). According to Aalberg et al. (Reference Aalberg, de Vreese, Strömbäck, de Vreese, Esser and Hopmann2017), the thematic agenda on programmatic proposals (issue frame) and the strategic communication (game frame) to obtain votes are key elements of current public communication. The topics of the thematic agenda depend on the most relevant themes during a specific time frame. Conversely, the frames under the game frame are found deductively (see Appendix B for details). Categories were created to be exclusive and exhaustive; thus, it is not possible to code more than one frame for each tweet.

Beyond that, the analysis of frequencies is mixed with bilateral tests using Bonferroni correction. This test allows us to check statistically significant differences between the actors, illustrating how the heads of government and the fact-checking organizations managed the health crisis. Other studies have also used this approach to measure anti-vaccine controversies (Rivas-de-Roca et al., Reference Rivas-de-Roca, García-Gordillo and Rojas-Torrijos2021), but our research broadens the scope by carrying out an analysis of keywords. A corpus of words (3,778) from the tweets was extracted and managed using the AntConc program (57) to find the most used keywords and their combinations (see Appendix C). AntConc is a multipurpose corpus analysis toolkit, which we use to shed light on the discursive marks characterizing global political storytelling on Twitter. As this analysis uses unigram and a word may have different meanings, we include it in an appendix as an explorative study.

Results

Political leaders and COVID-19 vaccination

The distribution of specific topics and strategies can be seen as an indicator of the leaders’ agendas, delving into how a pro-vaccine campaign was built. Table 1 offers findings to explore this point. Cross-language comparison was implemented using a codebook based on wide categories that have already been employed in countries with different languages (Aalberg et al., Reference Aalberg, de Vreese, Strömbäck, de Vreese, Esser and Hopmann2017).

Table 1. Distribution of the thematic and strategic agenda on Twitter according to leaders (percent).

Notes: Data with a significance level of .05 (*), based on two-tailed tests for the column proportion (Bonferroni correction).

All the leaders gave great importance to vaccination campaigns, which is statistically significant within the sample. This is reinforced by remarkable mentions of vaccination data in the United States (14.4% for Joe Biden) and the United Kingdom (34.8% for Boris Johnson). By contrast, there is a preference for foreign affairs in the tweets of Emmanuel Macron (20.3%) and Pedro Sánchez (26.8%) that is not observed in Anglo-Saxon countries.

Classic thematic issues such as the economy were not very common, but we detect an exception in the social policy of Joe Biden (18.5%). Besides that, strategic communication (game frame) was infrequent. Only the Spanish prime minister used one strategy item (horse race and governing frame) in a significant way (20.3%). This finding exposes how the COVID-19 vaccination was not fostered by a conflictive approach, as the leaders focused on the campaign to promote vaccination. Nevertheless, the high percentage of a specific game frame in Spain or the role attributed to social policy in the United States reveals that the campaign manifested different characteristics by country.

In terms of propaganda mechanisms, we found that political leaders usually resorted to them on social networks with the aim of spreading their messages, which aligns with previous literature (Lee & Xenos, Reference Lee and Xenos2019). Table 2 reports on the discourse of the heads of government during the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. Specifically, it shows that issues and strategies were mostly applied in a rhetorical way. Hence, fact-checking initiatives must tackle this content. Appeal to emotion and emphasis were the most used categories, but some exceptions are also reported.

Table 2. Propaganda mechanisms on Twitter by leader (percent).

Notes: Data with a significance level of .05 (*), based on two-tailed tests for the column proportion (Bonferroni correction).

Appeals, either to emotion (30%) or to authority (23.5%), were the key mechanisms for the U.S. president. Emphasis (19.9%) was also important for Biden, who tried to build an image of authority based on appealing to feelings in a reiterative way. Conversely, Johnson avoided an emotional perspective. He prioritized emphasis (28.9%) and speaking through other sources (24.3%) as the main trends. The fact of speaking through other sources meant to put the focus on additional actors in the public sphere that served to disseminate Johnson’s positions.

Regarding France, Macron mostly developed selecting information in his tweets (36.8%), which implies the use of information that benefits the leader (see Figure 1). This practice was followed by emphasis (22.9%) and appeal to emotion (19.5%). Likewise, Sánchez employed selecting information (41.2%) and appeal to emotion (23.9%) in a significant way, while the rest of leaders highly used emphasis, Sánchez preferred other options such as opinions as facts, which were found in 19.8% of his tweets. The Spanish politician was the only one to apply the latter in a significant way, promoting a belief that his opinions could be evaluated as real facts.

Figure 1. Tweet of Macron on selecting information. English translation: “The care of long COVID patients will be developed across the territory because no one should be left alone.”

Taken together, the appeals to emotion and emphasis were the most shared propaganda mechanisms between the leaders, although there are some differences, and selecting information was also important for half the sample. Therefore, it seems that the communication is strongly emotional and repetitive in order to catch the attention of the voters. The common findings may be illustrative of a similar strategy by the heads of governments in Western democracies.

The role of fact-checking platforms against propaganda on Twitter

After identifying the common propaganda mechanisms of leaders, Table 3 identifies the main strategies verified by fact-checking platforms. We collected data from these fact-checking platforms’ Twitter accounts and manually coded their tweets. When fact-checkers claim that a statement is true or false, or rate it based on the likelihood that it is true, they may verify propaganda.

Table 3. Propaganda mechanisms on Twitter by fact-checking service (percent).

Notes: Data with a significance level of .05 (*), based on two-tailed tests for the column proportion (Bonferroni correction).

Accordingly, Table 3 does not refer to the mechanisms used by political leaders and picked up by fact-checking websites, but to the propaganda mechanisms presented directly on the fact-checking websites. This content could be spread by other actors beyond the selected political leaders. Regarding cross-language, the wide categories were supported by the collaboration of colleagues from the four countries to ensure the linguistic validity of propaganda mechanisms.

On this matter, remarkable differences were found. Selecting information was the most used mechanism for PolitiFact in the United States (93%) and Maldita.es in Spain (53.6%), but in the latter country, emphasis was also significant (23.2%). The type of propaganda verified by PolitiFact was scarcely plural, as shown by the large percentage achieved in a single category.

In the same vein, the number of propaganda mechanisms checked by Full Fact in the United Kingdom was limited. However, their communicative actions focused on appeal to ignorance (81.2%), which is different from the rest of the fact-checking services. This means that the British service had to deal with stories related to topics ignored among citizens. By contrast, the French company Les Décodeurs offered a plural approach, facing many different propaganda strategies.

Moreover, 20.9% of the tweets of Les Décodeurs did not include any propaganda mechanism. The finding is noteworthy, since all the work of the other fact-checkers referred to propaganda concepts. The reasons why propaganda in France is not always present should be explored in future research. National factors such as political cultures, media systems, or journalistic cultures may be assessed.

A connection between the tweets of the heads of government and fact-checking projects seems possible regarding the COVID-19 vaccination. The tweets of the latter respond to the leaders, as they are mostly propaganda. Nevertheless, there is no correspondence between the mechanisms cited. For instance, tendentious claims were not present for Macron, but they were key in the verification process of Les Décodeurs.

The mismatch in terms of strategies was also found in the United States and the United Kingdom. In the United States, PolitiFact focused on selecting information and Biden did so on appeals to emotion and authority; meanwhile, the preference of British prime minister Johnson for emphasis and speaking through other sources did not match the large presence of appeal to ignorance for Full Fact.

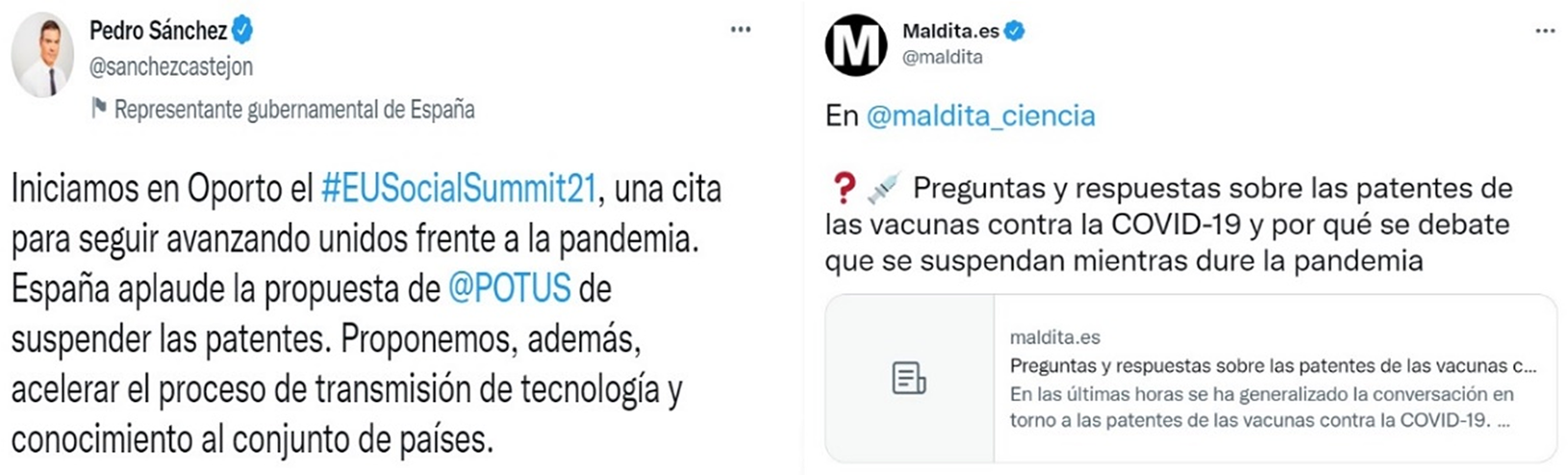

In contrast, the high use of selecting information of Sánchez in Spain corresponds to the number of tweets verifying this strategy by the Spanish fact-checker (Maldita.es). Thus, in the case of Spain, the verification tweets work almost as a perfect response to the ideas disseminated by Prime Minister Sánchez on Twitter, as seen for vaccine patents (see Figure 2). According to the data, the actions of Maldita.es depended much more on the propaganda shared by the political leader.

Figure 2. Tweets of Sánchez and Maldita.es about vaccine patents. English translation, Sánchez: “We started the #EUSocialSummit21 in Porto, an appointment to continue advancing together against the pandemic. Spain supports @POTUS’s proposal to suspend patents. We also propose accelerating the process of transferring technology and knowledge to all countries.” English translation, Maldita.es: “In Maldita Science. Questions and answers about the patents of the COVID-19 vaccines and why it is discussed whether they should be suspended during the pandemic.”

Conclusions and discussion

This article aimed to examine the flow of information between political leaders and fact-checking projects about the COVID-19 vaccination campaign, since they are very relevant public actors. Like any other journalistic service, fact-checkers are committed to performing on the basis of true information. However, this goal can be disturbed by the proactive action of political leaders, particularly in emergency situations that depend on institutional information. Against a backdrop of mass vaccination that offered hope after months of lockdowns, this study answers the initial research questions and contributes to the budding literature on propaganda and social media, providing three interrelated findings.

Our first contribution furthers our understanding of how the heads of government used propaganda. Most of them resorted to it frequently, showing that these mechanisms are evaluated as influential on public opinion. Specifically, appeals to emotion and emphasis were the most used propaganda mechanisms, but with some differences among the leaders. For example, emphasis was a recurring tool in the Anglo-Saxon countries, while in France and Spain, selecting information was preferred. The differences found do not avoid a massive propagandistic communication. These findings probably go beyond the pandemic and reveal a disruptive practice that could affect trust in vaccination.

Second, we explored the most important mechanisms by each leader. For Biden, appeals to emotion and authority as well as emphasis were encountered as favored propaganda practices. Johnson agreed with Biden on the role of emphasis, but the British prime minister frequently used speaking through other sources and attributions, describing an approach centered on other actors mentioned in an intentional way. Regarding Macron, a personalized trend was found by selecting information that benefited him, as shown in Figure 1. Emphasis and appeal to emotion were also used. Lastly, in Spain, Sánchez combined the aforementioned selection of information and appeal to emotion with selecting information (41.2%), appeal to emotion (23.9%), and opinions as facts (19.8%) in a significant way.

Our third contribution offers insightful findings on the practices of fact-checking services, which had to deal with emotional and opinionative content. Accordingly, the differences in the use of propaganda were even larger, since the number of mechanisms cited was limited in most of the agencies considered. Only a few categories were collected. There seems to be a connection between the tweets of the heads of government and the fact-checking projects, but there is not a perfect correspondence in terms of the strategies chosen. We should discuss whether the agenda developed aligns with the leaders, which would provide evidence that those actors are the main object for fact-checking.

In short, our results reveal clearly propagandistic communication by the political leaders, based on the tools of emphasis and appeal to emotion. Both actors belong to national spheres, but some of the interests are the same as the international field since they employ propaganda. Taking these insights together, we argue that fallacious political language could damage trust in a crisis situation. Against this backdrop, the fact-checking initiatives do a valuable task of avoiding the spread of disinformation, responding to some of the strategies of politicians.

This study contributes to the wider scholarly debate on the impact of social media on democracy. Prior scholarship has described a lack of knowledge acquisition on these platforms (Gil de Zúñiga et al., Reference Gil de Zúñiga, Weeks and Ardèvol-Abreu2017), but also that the accidental exposure to politics on social media may work as a participation equalizer (Valeriani & Vaccari, Reference Valeriani and Vaccari2016). This kind of exposure does not prevent the negative effects of these networks on vaccine confidence (Bertin et al., Reference Bertin, Nera and Delouvée2020). Twitter is a noteworthy space in which these debates on health issues take place, even though a true public conversation is difficult there (Milani et al., Reference Milani, Weitkamp and Webb2020).

Our article’s principal implications concern the communicative consequences of COVID-19. During the pandemic, inequalities in news consumption were reduced thanks to the resurgence of legacy media (Casero-Ripollés, Reference Casero‐Ripollés2020). However, the huge presence of hoaxes about COVID-19 in the so-called post-truth era fosters the interest of fact-checking services, independent or linked to established media outlets (Rúas-Araújo et al., Reference Rúas-Araújo, Rodríguez-Martelo and Máiz-Bar2022), which verify part of the multiple messages disseminated through digital technologies. In addition, addressing communication in a crisis situation connects with credibility. For example, vaccines provided an opportunity for democracy to improve good governance. Our empirical findings show the predominance of propaganda in the leaders’ communication and a divergence between the politicians and fact-checkers. In this regard, the framing theory still looks valid for social media (Cartwright et al., Reference Cartwright, Stepanova and Xue2019).

Finally, we note that the sampling method was a limitation of the study. The sampling generated unequal sample sizes; thus, the results should be considered as interesting cases in a highly relevant time frame. In every country studied, there were other recognized fact-checkers such as FactCheck and Snopes in the United States or Newtral in Spain. The time did not allow us to expand the sample, so our article focused on a single long-standing project in each country. Other geographical contexts and the level of credibility of each fact-checker should be considered to better understand the different characteristics of a common public health campaign.

We sought to evaluate the scope of political messages in the fact-checking accounts, and consequently their influence on the social audience and their democratic implications. The keyword list is short and does not encompass the use of verbal language. There are additional limitations, but the scant differences in data volume make the current model enough to examine communication about the vaccination. Future research may consider expanding the present analysis by using bigger samples and qualitative observation of the elements involved in propaganda, which reached another milestone in the digital environment during the COVID-19 vaccination.

Data availability statement

This article earned the Open Materials badge for open scientific practices. The materials that support the findings of this study and the award of this badge are openly available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/MB4K3.

Appendix A. Example tweets for pre-defined categories on propaganda mechanisms

Appeal to authority (PM1)

@POTUS On Saturday, the FDA issued an emergency use authorization for the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine. Dr. Fauci sat down to answer your questions.

Appeal to emotion (PM2)

@sanchezcastejon Su labor es clave. Se han dejado la piel durante esta pandemia y ahora están trabajando contra reloj para avanzar en la vacunación de forma rápida y eficaz. Gracias a las enfermeras/os por su entrega y dedicación. Sigamos apoyando a esta profesión #DíaInternacionalDeLaEnfermería.

Translation into English: “Their task is key. They have worked their butt off during this pandemic and are now working around the clock to advance vaccination quickly and effectively. Thanks to the nurses for their delivery and dedication. Let’s continue to support this profession #InternationalNursingDay.”

Fallacy against the man (PM3)

@decodeurs Comment les antivax font croire que Christian Estrosi a feint de se faire vacciner contre le Covid-19.

Translation into English: “How antivax make believe that Christian Estrosi pretended to be vaccinated against Covid-19.”

Appeal to force (PM4)

@BorisJohnson Our hospitals are under more pressure than at any other time since the start of the pandemic, and infection rates continue to soar at an alarming rate. The vaccine rollout has given us renewed hope, but it’s critical for now we stay at home, protect the NHS and save lives.

Appeal to ignorance (PM5)

@fullfact An old image has been reused with claims that it depicts scenes from the current wave of Covid-19 in India. But the footage was taken after a gas leak in 2020.

Attributions (PM6)

@BorisJohnson I am focused on beating COVID, saving lives and livelihoods and rolling out vaccines, but I am also determined we get on with fulfilling the promises we made to the British people. In next week’s #QueensSpeech we will go further to unite and level up.

Tendentious claims (PM7)

@decodeurs Non, on ne peut pas affirmer que le covid a causé « zéro mort de moins de 44 ans »

Translation into English: “No, we cannot say that covid has caused zero deaths under the age of 44.”

Emphasis (PM8)

@maldita En @maldita_ciencia. Por qué todas las vacunas pasan la fase 4 y por qué no es cierto que las vacunas aprobadas contra el coronavirus no sean ‘una vacuna al uso’ sino ‘una vacuna experimental’.

Translation into English: “In Maldita Science. Why all vaccines pass phase 4 and why it is not true that the approved vaccines against the coronavirus are not a vaccine to use but an experimental vaccine.”

Stereotypes (PM9)

@PolitiFact Thanks to @docdanmd who gave us an exclusive interview about how he reaches vaccine hesitant communities of color, and meets them where they are.

False analogy (PM10)

@decodeurs Covid-19 : pas contagieux, les asymptomatiques ? Gare à une étude sur « 10 millions d’habitants » mal interprétée.

Translation into English: “Covid-19: not contagious, asymptomatic? Beware of a study on ‘10 million inhabitants’ misinterpreted”.

Speaking through other sources (PM11)

@fullfact Just to confirm: Covid-19 vaccines do not contain artificial intelligence, affect fertility or transmit anything to unvaccinated people - despite what you might have read on David Icke’s website…

Opinions as facts (PM12)

@sanchezcastejon La propiedad intelectual no puede ser un obstáculo para garantizar el acceso equitativo y universal a las vacunas. No es solo una cuestión de justicia, es la clave para poner fin definitivamente a la pandemia.

Translation into English: “Intellectual property cannot be an obstacle to guarantee equitable and universal access to vaccines. It is not just a question of justice; it is the key to definitively ending the pandemic.”

Selecting information (PM13)

@Emmanuel Macron + 510 000 vaccinations aujourd’hui. On continue d’accélérer !

Translation into English: + 510,000 vaccinations today. We continue to accelerate!

Use of labels (PM14)

*Not found. It occurs when a faulty label is applied to a person or organization, impacting on the relationship between the labelled and the public.

Appendix B. Categories on issue and game frames

Appendix C. Keywords for global political leaders

The analysis of the most frequent keywords provides information about the leaders’ speeches. Their messages on Twitter moved from building unity to the appeal to get vaccinated.

-

1. Appeal to action (get boosted). All leaders alluded to verbs that show to what extent their governments develop measures to enhance people’s life during a very turbulent context. There are not only references to these measures (care, ensure, achieve, or relief), but also to call to citizen’s action (join, come).

-

2. Building unity against the pandemic. The words most used by the leaders were nationals of the country or people. References to the community, the territory and its regions or the name of the country were also frequent. With these keywords, the politicians define a purpose of encouraging the feeling of belonging to a community. This assumption is perceived as the basis to accept restrictions.

-

3. Health dimension of the pandemic. Since the vaccination campaign was the main topic, the heads of governments included a classic set of words related to the health crisis (lives, pandemic, virus, or variant). The need to face the pandemic (fight, efforts, or head to) was combined with vaccines, the health system or wearing masks.

-

4. Additional priorities. As the COVID-19 impacts many different areas in society, several political priorities were highlighted in the tweets. Jobs, business, hospitality industry, education, and science were the most frequent, showing an attempt to bring the politicians closer to citizens’ needs.

-

5. Reinforcement. Several temporal references (today, moment, week) were employed to reinforce the speeches.

As a result, the keywords posted on Twitter by the political leaders are related to the issues that featured their communication. Although strategies (game frames) were not recurring in their tweets, it is highlighted the aim of building unity and appealing to action within the pandemic. This fight against the pandemic is presented from a positive approach that focuses on the national community and how the virus could mean a chance for resilience.