Women are underrepresented across political science disciplines (APSA 2005), which underscores the need for effective approaches that promote and retain women who pursue American politics, political theory, international relations, and comparative politics at the undergraduate level and throughout the “academic pathway.” Women experience unique social challenges when entering university, including feelings of marginalization in male-dominated fields (Ceci, Williams, and Barnett Reference Ceci, Williams and Barnett2009; Steele, James, and Barnett Reference Steele, James and Barnett2002); low self-efficacy (Betz and Hackett Reference Betz and Hackett1981); and discrimination in and out of the classroom (Banks Reference Banks1988; Moss-Racusin et al. Reference Moss-Racusin, Dovidio, Brescoll, Graham and Handelsman2012). In the political sciences, previous work has demonstrated the susceptibility of women to “stereotype threat” in political knowledge (McGlone, Aronson, and Kobrynowicz Reference McGlone, Aronson and Kobrynowicz2006). Stereotype threat is defined as concern about confirming a negative stereotype about one’s group, and it occurs in competitive and evaluative contexts such as a classroom or a testing environment (Steele Reference Steele1997). For example, in one study, women performed better on a difficult math test when the examiner described the test as not producing gender differences. In this case, the stereotype threat was reduced by lowering the sense of risk for the student to be judged based on the stereotype that representatives of her gender (i.e., women) are poor at math (Spencer, Steele, and Quinn Reference Spencer, Steele and Quinn1999). The outcome of repeated exposure to social challenges for women is their attrition at the postgraduate, postdoctoral, and faculty levels of academic rank (APSA 2005; Bates, Jenkins, and Pflaeger Reference Bates, Jenkins and Pflaeger2012; Monroe and Chiu Reference Monroe and Chiu2010; Timperley Reference Timperley2013). Among faculty, Timperly (Reference Timperley2013) identified several factors from the literature that serve as barriers that prevent women’s progression in political science. Examples include a negative culture of research that discourages the examination of questions that fall outside of the more “traditional” scope of political science (e.g., gender and family) (Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008); a “chilly” professional climate that devalues junior faculty who are women (Anonymous 1999); and a “double bind” that results from conflicts between gender stereotypes and professional expectations (Ong et al. Reference Ong, Wright, Espinosa and Orfield2011). Women in political science also engage in professional service more than their male peers (Mitchell and Hesli Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013), which may contribute to their lower publication rates across academic rank (Hesli and Lee Reference Hesli and Lee2011).

Examining college experiences may be particularly important because peer interactions and academic performance impact students while they navigate identities as competent political scientists.

Although gender inequality in political science has been documented primarily at the faculty level, we expect that students’ experiences as undergraduates influence these later outcomes. We also can take cues from research on undergraduates in male-dominated STEM fields, where attrition of women is both progressive (i.e., their proportion declines in more advanced positions) and persistent (i.e., little progress has been made despite efforts), with numerous and complex underlying drivers (Blickenstaff Reference Blickenstaff2005; Burke and Mattis Reference Burke and Mattis2007). Examining college experiences may be particularly important because peer interactions and academic performance impact students while they navigate identities as competent political scientists. To our knowledge, this article presents the first study that documents academic inequity during the course of a semester in an undergraduate political science classroom. It does so by first quantifying whole-class participation and then by presenting a qualitative investigation into the perspectives of women and men about the classroom environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study took place at the University of Bergen (UiB), a public university located in Bergen, Norway. Our study focused on one introductory comparative-politics course (i.e., SAMPOL 100) that is recommended to all comparative-politics majors and is attended primarily by students in their first semester at UiB. In the fall of 2016, SAMPOL 100 took place on campus in a traditional lecture hall (i.e., 130 students completed the course).Footnote 1 The gender composition of the class was 48% women. In our analyses, we expected that 48% of student participants would be women unless something prevented that group from speaking, and we tested the actual observed percentage against this expected value.

CLASSROOM OBSERVATIONS

We used an observation protocol that characterized seven in-class interactions between students and the instructor during an approximate two-hour (i.e., two 45-minute) class period (Eddy, Brownell, and Wenderoth Reference Eddy, Brownell and Wenderoth2014). For each type of interaction, observers noted the gender of students who participated. If the gender identity of a student was unclear, observers asked the instructor for clarification. In our dataset, students interacted with instructors using two of the seven different types of common interaction classifications (see Ballen et al. Reference Ballen, Danielsen, Jørgensen, Grytnes and Cotner2017, appendix 1): (1) asking a spontaneous question or making a comment, and (2) volunteering an answer following an instructor-generated question. The course is designed as an introduction to the subject and the department: the lead instructor gives five lectures at the beginning of the course, followed by 10 individual lectures from various faculty members (presenting area cases). The intended benefit of the course structure is to give students exposure to the faculty and expertise during their first semester. One unintended consequence may be that students—particularly women—feel less comfortable participating when instructors change every week. Therefore, in our analyses, we considered the effect of gender on student participation in guest-lecturer classes separately (N = five lectures and 55 observations) from our analysis of participation during the lead instructor’s lectures (N = three lectures and 77 observations). We only included instructors who had a total of five or more student interactions in any of the pooled categories. This led to the exclusion of two guest lecturers who were both men. The included guest lecturers were two women and three men, and the lead instructor was a woman.

QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

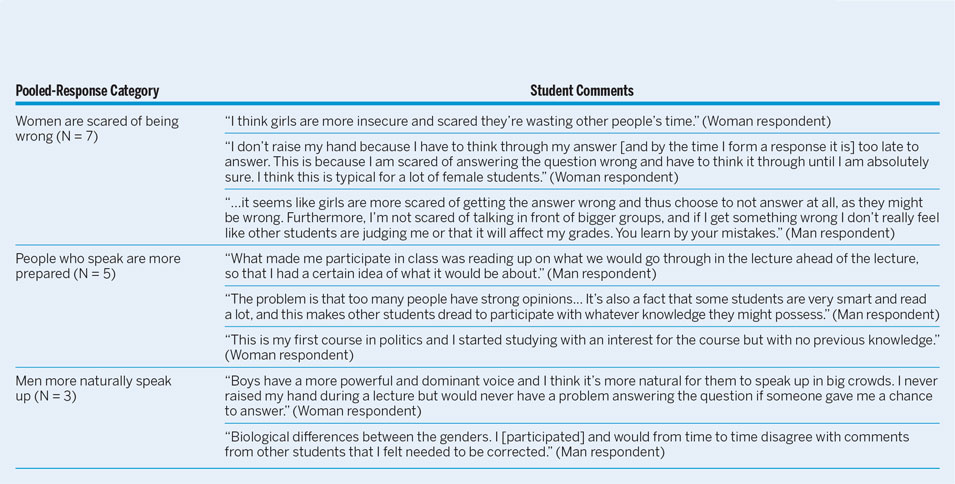

When the semester ended, the lead instructor revealed to students that in-class observers quantified whole-class participation to examine gendered behaviors. After sharing the observation data, the instructor invited students to take an online survey designed to elicit their responses to the data. Survey participation was anonymous and voluntary, and the participant’s gender was the only personal information collected. Specifically, students were asked to describe their views “as to why there is such a huge difference between participation of women and men in class.” Students could answer this broad question as they saw fit by focusing on one of the following questions: (1) What could explain this?; (2) What made you participate during lectures?; or (3) What prevented you from participating? Of the approximate 90 students who regularly attended the lectures, 17 (19%) participated in the survey. After reviewing student responses, the research team coded the responses according to three broad themes, as listed in table 1.

Table 1 Students’ Views on Why Women Participated Less in the Classroom (N = 17)

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

We ran analyses separately for each type of student–instructor interaction (i.e., spontaneous question or comment and volunteer response) as well as all combined interactions for guest lecturers’ classes and the lead lecturer’s classes. To assess whether there were gendered patterns in response to each interaction type, we used a one-sample t-test to examine whether the proportion of interactions involving women in a class is more or less than expected (given the number of women in the class) in each type of interaction individually and then all interactions combined.

The number of volunteer responses attributed to women (i.e., 5 of 37) was significantly lower (i.e., t(36) = 6.76; p < 0.0001) than expected based on the number of women in the classroom. In other words, after an instructor posed a question to students, a woman was less likely than a man to raise her hand.

RESULTS

In the 2016 fall semester, we observed 55 interactions among guest lecturers during five class periods; in the lead instructor’s classes, we observed 77 interactions during three class periods.

Among the guest lecturers, we found significant differences between the number of women enrolled in the class (48%) and the number of questions asked or spontaneous comments made (i.e., without being prompted by the instructor) by women (i.e., 2 of 18; t(17) = 5.36; two-tailed p < 0.0001). The number of volunteer responses attributed to women (i.e., 5 of 37) was significantly lower (i.e., t(36) = 6.76; p < 0.0001) than expected based on the number of women in the classroom. In other words, after an instructor posed a question to students, a woman was less likely than a man to raise her hand. Combined, the total number of women who spoke in the classroom during the observed class periods was significantly lower than expected based on the women who were in the classroom (i.e., seven of 55; t(54) = 8.66; p < 0.0001) (figure 1). In the lead instructor’s lectures, we also found a significant difference between the number of women enrolled in the class (48%) and the number of spontaneous questions asked or comments made by women (0 of 13; p < 0.0001) or the number of volunteer responses attributed to women (i.e., 11 of 64; t(63) = 7.32; two-tailed p < 0.0001). When we combined these values, the total number of women who spoke during the lead instructor’s classes was significantly less than expected (i.e., 11 of 77; t(76) = 9.40; two-tailed p < 0.0001) (see figure 1).

Figure 1 Gender Gap in Participation in Comparative Politics Course

Observed (gray bars dashed lines) versus expected (black bars) proportions of participants who are women in whole-classroom discussions in introductory comparative politics across randomly observed (A) guest lecturers’ classes, (B) lead instructors’ classes, and (C) a combined summary of all guest-lecturer and lead instructor’s classes. Shown are two different types of instructor–student interactions in the classroom, including volunteer and spontaneous responses. All observed proportions of participating students who are women were significantly less than expected given the number of women in the classroom; therefore, all p < 0.05.

Our second objective, accomplished through interviews with students, was to qualitatively explore barriers in the classroom that may prevent women from participating (N = 17) (see table 1). The participants reported many reasons why women do not participate in class; however, three recurring themes that were identified from the interviews became apparent: (1) women are scared of being wrong, (2) people who speak are more prepared, and (3) men more naturally speak. Of the 17 student responses, we categorized 15 responses (88%) in one of the three pooled themes, as outlined in table 1.

DISCUSSION

Although Norway is lauded as one of the most politically equitable countries in the world (Bekhouche et al. Reference Bekhouche, Hausmann, Tyson and Zahidi2013), undergraduate women in an introductory comparative-politics course spoke up significantly less than men across all measures of participation—a result more dramatic than previously observed in some STEM courses (Ballen et al. Reference Ballen, Danielsen, Jørgensen, Grytnes and Cotner2017; Eddy, Brownell, and Wenderoth Reference Eddy, Brownell and Wenderoth2014). Students reported that the reluctance of women to participate may be due to fear of being wrong; because those who speak in class—woman or man—are more prepared and knowledgeable about the subject; or because men more naturally speak up in groups.

Although our results revealed a strong pattern, we recognized that a limitation of this study is that the data presented was from only one classroom and one semester. Furthermore, the origin of the observed gap in participation remains unclear, as well as the extent of the gender gap in student performance and attrition in political science. Although students suggested that those who speak in class are more prepared or have more knowledge, we are not aware of research that supports those claims. This would require either measures of preparation, or how much students study the material before the lecture, or a gauge of student knowledge through validated knowledge-assessment inventories. Another possibility is that women experience a higher susceptibility to stereotype threat, which inhibits academic performance of individuals who identify within domains where negative-ability stereotypes exist. Previous research demonstrated how this phenomenon affects ethnic minorities (Nguyen and Ryan Reference Nguyen and Ryan2008; Steele Reference Steele1997; Steele and Aronson Reference Steele and Aronson1995) and women (e.g., within male-stereotyped STEM disciplines) (Cheryan et al. Reference Cheryan, Plaut, Davies and Steele2009; Spencer, Steele, and Quinn Reference Spencer, Steele and Quinn1999). Fortunately, empirical research demonstrates multiple strategies to combat stereotype threat in the classroom, such as removing cues that endorse or confirm stereotypes (Cheryan et al. Reference Cheryan, Plaut, Davies and Steele2009; Danaher and Crandall Reference Danaher and Crandall2008; Logel et al. Reference Logel, Walton, Spencer, Iserman, Hippel and Bell2009; Steele and Aronson Reference Steele and Aronson1995). For example, Cheryan et al. (Reference Cheryan, Plaut, Davies and Steele2009) showed that women lose interest in computer-science classrooms when objects in the room signal that the people there are geeky men (e.g., Star Trek posters and empty soda cans from all-night coding sessions) as opposed to a neutral physical environment. If the décor sends signals about who belongs in a computer-science learning environment, a semester focused on powerful male leaders in history also may send a strong message to students—even if the instructor does not intend to convey these messages through course content.

If the décor sends signals about who belongs in a computer-science learning environment, a semester focused on powerful male leaders in history also may send a strong message to students—even if the instructor does not intend to convey these messages through course content.

A clear avenue for future research is to examine the effects of presenting diverse political leaders in a comparative-politics course and to quantify similar output variables (e.g., participation, performance, and intention to stay in the discipline). Other examples of ways to reduce stereotype threat and promote inclusivity include using gender- and culture-fair tests and curriculum materials to ensure that there are no biases against certain groups in academic-performance measurements (Good, Aronson, and Harder Reference Good, Aronson and Harder2008; Spencer, Steele, and Quinn Reference Spencer, Steele and Quinn1999; Steele and Aronson Reference Steele and Aronson1995); conveying to students that diversity is valued (Purdie-Vaughns et al. Reference Purdie-Vaughns, Steele, Davies, Ditlmann and Crosby2008); supporting students’ sense of belonging (Walton and Cohen Reference Walton and Cohen2011); engaging students in value-affirmation activities (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, Apfel and Brzustoski2009; Martens et al. Reference Martens, Johns, Greenberg and Schimel2006); and improving intergroup relations (Page-Gould, Mendoza-Denton, and Tropp Reference Page-Gould, Mendoza-Denton and Tropp2008; Steele Reference Steele1997). In addition, women may feel marginalized due to lack of exposure to other women as examples featured in lectures. Women are underrepresented globally in politics (“The Global Gender Gap Report” 2016), a phenomenon that may be self-fulfilling: the representation of political power as exclusively male may affect the behavior and performance of women. Therefore, a simple solution may be to create a critical mass by increasing visibility of underrepresented groups in the field (Cotner et al. Reference Cotner, Ballen, Christopher Brooks and Moore2011; Murphy, Steele, and Gross Reference Murphy, Steele and Gross2007; Purdie-Vaughns et al. Reference Purdie-Vaughns, Steele, Davies, Ditlmann and Crosby2008). Women also may be subject to the “double bind” of conflicting expectations. In whole-class discussion, women face limited options—they can choose to be more than, less than, or similarly opinionated and knowledgeable as male students. Acting more opinionated and outspoken counters peer expectations of feminine behavior, resulting in potential social costs of speaking out regularly (Jamieson Reference Jamieson1995). Making participation part of the students’ grade or using a random number generator to call on students may normalize outspoken behavior and lower the perceived threat of classroom participation (Eddy, Brownell, and Wenderoth Reference Eddy, Brownell and Wenderoth2014). Other simple in-class interventions that benefit underrepresented groups such as women include small-group discussions (Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Eddy, McDonough, Smith, Okoroafor, Jordt and Wenderoth2014; Haak et al. Reference Haak, Lambers, Pitre and Freeman2011; Lorenzo, Crouch, and Mazur Reference Lorenzo, Crouch and Mazur2006; Pollock, Hamann, and Wilson Reference Pollock, Hamann and Wilson2011) and women-majority group work.

Our assessment presents political science as a discipline with a unique opportunity to apply and monitor evidence-based methodologies to close the classroom gender gap. The striking lack of participation of women is a problem in urgent need of attention. If promising young political scientists do not speak up in the classroom, we cannot expect them to assert their opinions farther along the academic pathway or in a political arena outside of academia. Fostering an inclusive classroom environment that explicitly values diversity will improve access to political science for all students.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000045.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Marie Danielsen for help with data collection and Oddfrid T. Kårstad Førland, Vigdis Vandvik, and Lucas Jeno for additional support. This research was approved by NSD Prosjektnr 46727 and funded by the Centre of Excellence in Biology Education (bioCEED) at the University of Bergen and the Department of Biology Teaching and Learning at the University of Minnesota. Cissy Ballen was supported by a Research Council of Norway Mobility Grant (Proposal No. 261529) awarded to Sehoya Cotner.