In this chapter, I consider efforts to imagine – and perhaps try to produce – ignorant experts as part of some sort of social form. The form might be more or less loose – a group of brokers and translators, a network, a community of practice, a social movement, a field, and so on. These efforts are also organised around socialising a style of reform, or an imagined relationship between ignorance and implementation work. These efforts thus limit the use of ignorance work, frame the horizons of ignorance claims, denote preferred types of ignorance and implementation work, and produce relationships between the two.

There are many such efforts. They range from the imagined ‘wear[y]’ and ‘cynical’ solo practitioner exasperated with the knowledge ‘that next year they may well have to adapt again to the latest fad’ that papers over the empty spaces where rule of law should be (here, ignorance work is in a relation of non-relation to implementation work); to her imagined cousin, the solo practitioner committed to ongoing ‘critical reflection and learning’ about the rule of law (here, ignorance work and implementation work are coterminous and coextensive); to her imagined foil, the zealous normative or technical missionary for the rule of law, altogether committed to her institutional mandate (here, implementation work subsumes ignorance work); and beyond.Footnote 1

These efforts appear to me to be as yet inchoate – they seem to have a quality of perpetual emergence and not-quite-consolidation, perhaps unsurprisingly given their subject matter. I focus in this chapter on ‘problem-driven iterative adaptation’ (PDIA) as a specific effort to systematically organise and contain expert ignorance. I argue that the politics of PDIA lies in how it categorises legal questions or problems as more or less open-ended and contingent on extra-legal context, or more or less technical and closed. This is ultimately an attempt to shape the ongoing negotiation of the extent to which law is autonomous to politics.

PDIA, and other efforts like it, are not concerned with substituting or replacing law-giving sovereigns (with experts, for example). Rather, through expert ignorance, they recognise and reinforce the absence of the sovereign through a foundational act of self-denial and then cobble polities, governors, and governance together in an ad hoc fashion as the circumstances demand. At the same time, they are attempts to discipline and organise that ad hoc-ery. PDIA, for example, attempts to get reformers to continually redraw the law/politics divide and to do so in certain places and in certain ways, structuring polities, governors, and governance. It does so through a mode of social organisation that tries to influence reformers’ styles or sensibilities – that is, how they might relate ignorance and implementation work. This, in turn, negotiates experts’ social relationships with other domains of development.

To summarise: in previous chapters, I have argued that a performance analysis of action reveals the forms and autonomy of law emerging out of specific reforms. This can now be coupled to a sociological study of how reformers arrange themselves to be ignorant, ask questions, and structure contingency. In this chapter, I show the sociological relevance of PDIA projects, and terms of reference to hire rule of law reformers within development agencies: such arrangements shape and limit the legal and political consequences of rule of law performances, as well as the relationship of ignorant experts to the broader apparatus of development policy and practice. This opens these objects up to social scientific study (for example, through qualitative observation).

7.1 Problem-Driven Iterative Adaptation

Picking up where the previous chapter left off, it is my sense that the contemporary moment has been marked by a proliferation of the rule of law performer. Her means: a predilection for that self-questioning, coupled with a ferocious and tenacious instrumentalism. She might ask what the problem is (and how do we know?) and whether we can do anything about it (and how can we tell?). Or as Jackie would remind me for as long as I have worked with her: ‘As if there is something like “rule of law”… Start with the problem, see what you need’ and then work out what you can do. In Jackie’s comments, we can see a version of Fischer-Lichte’s openness (what is the problem?) and materiality (what, concretely, can we do?) coming together in a performance.

Today, we can see efforts to socially organise, frame, and discipline reformers’ self-questioning and their reform efforts. I focus here on PDIA, which has been influential on my work and will appear in subsequent chapters. PDIA and similar approaches have generated much academic and policy literature as well as donor action. They have shaped donor policies, programmes, and the allocation of funds: tens of millions of dollars of development aid from Britain and Europe have been spent using these approaches.Footnote 2

The key theorists of PDIA are Matt Andrews (a public administration specialist), Lant Pritchett (a former but long-time World Bank economist), and Michael Woolcock (a World Bank sociologist) – henceforth APW. APW are professors at the Harvard Kennedy School with long-standing relationships with the World Bank and other leading aid agencies. They place themselves as inheritors of a long line of pragmatic thinking since the 1950s:

In recent decades, a long line of venerable thinkers—Charles Lindblom in the 1950s, Albert Hirschmann [sic] in the 1960s and 1970s, David Korten in the 1980s, Dennis Rondinelli in the 1980s and 1990s, ‘complexity’ theorists in recent years (among others)—have argued [as we do] for taking a more adaptive or experimental approach to engaging with vexing development challenges.Footnote 3

Andrews has engaged directly with ignorance and makes explicit the place that it takes in his vision of development practice. He frames and shapes ignorance by typologising it analytically: there are, in his telling, six ‘types’ or ‘degrees’ of ‘unknowns’ for development policymakers to grapple with.Footnote 4 He goes on to argue how only some of them are amenable to existing forms of what I have called implementation work – ‘plan and control policy processes’, in his terms.Footnote 5 The rest, he suggests, must be embraced in their unknowability: ‘Ignoring our ignorance and pretending we know what we do not know may help us define and sell a project or policy today, but it will also ensure we are still working on the same policy challenges in years to come’.Footnote 6 In this vein, they want to think about action and its relationship to the limits of knowledge.

APW’s contribution to this inheritance is to ‘suggest that the ingredient missing from previous efforts has been the failure to mobilise a vibrant social movement of citizens, researchers, and development practitioners in support of the necessary change’.Footnote 7 Theirs is thus expressly an organisational and political project to shape the place of ignorance in development practice. This makes PDIA a useful object of analysis for my purposes, as APW seeks to give form to the formless object of expert ignorance while respecting its formlessness. More specifically, APW see themselves as building a movement to innovate responses to the practical and social challenges of institution building.

They take the following basic approach:Footnote 8

(1) they aim to solve particular problems in particular local contexts, as nominated and prioritised by local actors, via

(2) the creation of an ‘authorising environment’ for decision-making that encourages experimentation and ‘positive deviance’, which gives rise to

(3) active, ongoing, and experiential (and experimental) learning and the iterative feedback of lessons into new solutions, doing so by

(4) engaging broad sets of agents to ensure that reforms are viable, legitimate, and relevant – that is, they are politically supportable and practically implementable.

They seek to sustain momentum and political commitment towards a goal while keeping open the space to constantly reinterpret and revise that goal (in their terms, they ‘iterate’ between action and deferral).

The substance of PDIA work is thus to reconfigure the temporality of institutional reform, by deciding how quickly to iterate, and, in each iteration, to reassess whether to go fast or slow. It is also to reconfigure the spatiality of reform, by deciding in each iteration exactly where the problem is, where the solution might reside, and how to link the two (for example, by beginning with a problem of drug delivery to a primary healthcare post and over time articulating the problem as in fact about monopoly pricing of drugs leading to misappropriation along the supply chain). Finally, it is also to reconfigure the identity of participants in the reform process, reconsidering at each iteration the ‘broad set of agents’ relevant to the work, engaging new ones and detaching from older, less relevant ones. All of this is done in a ‘politically smart’ fashion, sensitive to the ‘authorising environment’, or extant distribution of power, that places limits on how fast reform can go, where it can take place, who might participate, and to what ends.Footnote 9

PDIA and rule of law reform share a denial of the content of its proponents’ expertise.Footnote 10 There is no specific set of tools, skills, or knowledge that outside agents bring; rather, reform proceeds on the basis of ‘[b]road-based local agency with only very specific and ‘humble’ support by external agents’.Footnote 11 Reform is a collaborative effort between outsiders and insiders using their social and institutional positions instrumentally or politically to realise their collaborative goal rather than using those positions to produce an authoritative answer to a problem. ‘[PDIA] requires taking calculated risks, embracing politics and being adaptable (thinking strategically but building on flexibility). Crucially, one needs the humility to accept that we do not have the answers and to accept, discuss and learn from failure’.Footnote 12 Indeed, PDIA people are meant to be simultaneously humble and savvy enough to know when they are not wanted; professional death is part of their professional repertoire. The distinction between the inside and outside of a reform process is thus simply the product of the reformer’s calculation of the risks involved in the project and the likelihood of success.Footnote 13

The only distinction between insiders and outsiders is thus their institutional position. Otherwise, for reform to be a success, everyone must cultivate a similar, doubled sensibility. Green, writing in alliance with APWFootnote 14 and arguing for a ‘power and systems approach’, asserts a set of

[C]haracteristics that activists should cultivate in order to flourish in complex systems, like curiosity, humility, self-awareness, and openness to a diversity of viewpoints. People become activists not to analyse the world, but to change it. We are impatient of anything that smacks of navel-gazing (one Oxfam head of advocacy dismissed my job as head of research as ‘beard stroking’). Consequently, we often fail to understand the history that lies behind the system we are facing, and thus we fail to ‘dance with’ the system. A PSA encourages us to nurture a genuine curiosity about the complex interwoven elements that characterize the systems we are trying to influence, without abandoning our desire to take action. We need to be observers and activists simultaneously.Footnote 15

These characteristics are reflected in much contemporary writing on PDIA.Footnote 16

Furthermore, within APW’s project are specific ways to organise a PDIA sensibility or style. There are other such projects, many of which emphasise the individual reformer’s sensibility, whether a humble and ethical bearer of expert office, a doubled ‘double-agent’ straddling the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of reform, or a charismatic leader.Footnote 17 PDIA is rooted in humble and ignorant experts confronted with highly complex institutions and systems that are free-floating and disentangled from the state. But it moves beyond the individual, envisaging ‘network[s]’,Footnote 18 classes of ‘innovators, pioneers, visionaries’,Footnote 19 and, more broadly, a ‘global social movement’ of creative individuals who are highly politically self-aware and can navigate political and contextual complexity.Footnote 20 APW want to show that ‘[adaptive] work is not haphazard and informal. It actually requires a lot of structure and discipline, and needs formal sanction and support’.Footnote 21

In sum, APW are concerned with what I have termed the production of the ‘shadows’: the creative work that reformers conduct to (re)produce and evanesce approximations and provisional determinations of the rule of law. PDIA is a political effort to recognise and organise an aesthetic sensibility towards the conduct of this work.

7.2 Reform and the Social Organisation of Reformers

To explore the consequences of this political effort, I turn back to one of the precursor texts to PDIA. In 2004, Pritchett and Woolcock wrote an article that analyses modes of decision-making in public service provision, as shown in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1 ‘Classifying modes of decision-making in key public services’

Discretionary | Non-discretionary | |

|---|---|---|

Transaction intensive | Practice | Programs |

Non-transaction intensive | Policies | (Procedures, rule) |

In their analysis, decisions ‘are discretionary to the extent that their delivery requires decisions by providers to be made on the basis of information that is important but inherently imperfectly specified and incomplete, thereby rendering them unable to be mechanised. As such, these decisions usually entail extensive professional (gained through training and/or experience) or informal context-specific knowledge’.Footnote 22 Transaction intensiveness ‘refers simply to the extent to which the delivery of a service (or an element of a service) requires a large number of transactions, nearly always involving some face-to-face contact’.Footnote 23 In simple terms, a spectrum between ‘discretion’ and ‘non-discretion’ is a way of talking about the contingent circumstances of the thing being reformed (i.e., its determinability). A spectrum between ‘transaction-intensive’ and ‘non-transaction-intensive’ is a way of talking about the contingent circumstances of the reformer’s authority.

The top left of their table – ‘practice’ – involves intense movement between ignorance and implementation work (in their terms, listening to context and responding using knowledge), with repeated (‘transaction-intensive’) efforts to adapt the relationship between the two as the circumstances demand. ‘Policies’ are less amenable to ignorance work, stabilised by the authority of the expert. ‘Programmes’ and ‘procedures’ are also less amenable to ignorance work, stabilised by shared clarity around the goals being pursued.

These distinctions are meaningful in a political sense. For example, Pritchett and Woolcock assert that policies, rules and legislation tend to require less contextual humility and more commitment to act: ‘lowering (or raising) the interest rate, devaluing (or not) the currency, setting a fiscal deficit target. These are all actions that intrinsically involve assessing the state of the world and taking appropriate action, but the implementation itself is not transaction-intensive…’Footnote 24 They continue: ‘The politics of policy reform may (or may not) require mass support, but “10 smart people” can handle the actual mechanics of policy reform’.Footnote 25

Yet this assertion is a product of an assumption about the underlying institutional architecture that makes implementation ‘not transaction-intensive’: a body of ‘10 smart people’ who have the power and institutional backing to determine that interest rate setting falls under the jurisdiction of their technical expertise. Doing so is a political choice. It is a means of distributing ignorance by ordering the relationship between ignorance work (the contextual ‘politics of policy reform’) and implementation work (its ‘actual mechanics’). For example, as Jacqueline Best points out, interest rate setting, currency valuation, and fiscal deficit targets are beset by ambiguities that could entail constant political adjustment and thus transaction-intensive implementation.Footnote 26

A way of thinking about this political choice is to imagine Pritchett and Woolcock’s classification of modes of decision-making as an analytic of where to draw different types of boundaries between law and politics – without being able to rely on a politically agreed-upon exercise of, fetters on, and suspension of regulation of arbitrariness. Pritchett and Woolcock are trying to build institutions, which will draw a set of boundaries between laws and politics; to do so, Pritchett and Woolcock try to draw boundaries between law and politics for the institution-reforming process. That process in turn relies on a background set of political assumptions about the underlying institutional architecture of reform.

To be clear, Pritchett and Woolcock are up-front about the specific institutional architecture that they inhabit as well as the politics of their analysis. For my purposes, they provide broader support for the proposition that analytic attempts to categorise certain rule of law reform decisions as more or less technical are in reality political interventions. I analogise their attempt to schematise modes of decision-making to a vocabulary to organise ‘ifs’. Like Stanislavski, they offer a way of framing decisions as more or less amenable to ignorance work, as well as an idea about the relationship between ignorance and implementation work. Where for Stanislavski that relationship was unidirectional (ignorance residing in the ‘subconscious’, which is then applied in and refracted through the materiality of the stage), for Pritchett and Woolcock, it is iterative – imperfect knowledge produces an imperfect decision, which changes the world while producing more knowledge to pursue the subsequent decision, and so on.

***

What does this attempt to give social form to ignorant experts look like? A full account would entail staging PDIA reforms within the context of APW’s efforts to build a global social movement. Here, I focus on the sociology of the latter to draw attention to some specific effects.

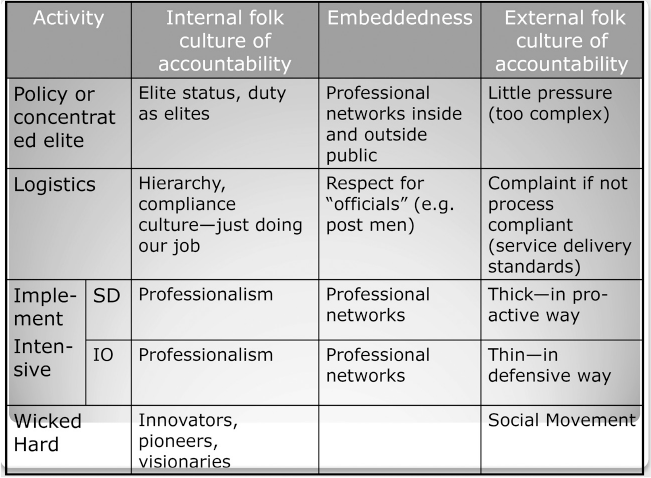

Lant Pritchett imagines the social relations that underpin PDIA in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2 Image of Lant Pritchett, ‘Folk and the Formula’, slide 40

The ‘activity’ in this table is a typology of problems that reform is trying to tackle; ‘embeddedness’ refers to the social structure in which the reformers tackling those problems are embedded; and the ‘folk culture[s] of accountability’ express the norms that tie reformers together within that social structure (the ‘internal’ culture) and that relate that structure to the outside world (the ‘external’ culture). I read internal culture here to be like the ‘backstage’ of expertise and external culture the ‘frontstage’. ‘Embeddedness’ would then describe the social structures that divide the frontstage from the backstage and shape the two. The empty space in the table above is thus suggestive of an absent sociology of PDIA as a form of expertise.

How might we describe the contours of this sociology? One set of contours might be the collapse of the relationship between the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ culture of reform; or the front- and backstage. Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff, convening a special journal issue of Public Administration and Development on recent experiences with PDIA, explore the relationship between PDIA reformers and the organisational cultures of donors. They discuss Eyben’s work on aid practitionersFootnote 27:

Eyben … discusses surreptitious approaches to reconciling such adaptation with donor requirements, what she calls ‘hiding relations.’ Her analysis describes how many local donor staff practice their own decoupling—subscribing to reporting responsibilities and accountability upward, on the one hand, while acting in ways that extend beyond these structured requirements and reframing their actions for reporting as needed.Footnote 28

This quite clearly sets out a backstage in front of which reform takes place. However, they immediately go on to state that

[i]n contrast to these hidden behaviors, Srivastava and Larizza … present an example of how World Bank staff found ways to incorporate PDIA to support the Sierra Leone public sector reform team in pursuing a flexible and contextually adaptive approach to implementation while creatively working within the limitations of Bank lending procedures.Footnote 29

Flexibility and continual adaptation were at the very forefront of the World Bank’s approach in Sierra Leone. That which was hidden in the backstage of reformers’ expertise was turned into material for their frontstage performance.

Another set of contours might be the form of the relationships between PDIA reformers. In referring to PDIA as a ‘global social movement’,Footnote 30 APW draw a clear contrast to other social forms, such as governments or bureaucratic donor institutions. Such a global social movement would have to network visionaries to share ideas (and hold each other accountable) without producing a hierarchy between reformers that might lead to overdetermined solutions to problems. The global social movement must thus be widespread and well-known enough to encompass and tie together ‘visionaries’; disciplinary and inspiring enough to stop other unhelpful norms (such as restrictive professional norms) influencing ‘visionaries’; and it must be flexible and mobile enough to support ‘gale[s] of creative destruction’ in institutional change.Footnote 31 In other words, PDIA requires a reflexive form of organisation; this form must be flexible enough to facilitate creativity while pushing against and withdrawing from other modes of organising expertise.

I am arguing that PDIA is in fact self-consciously organised as a moving combination of ignorance and implementation work in just the same way as it organises its object of reform. Indeed, PDIA remains ignorant about its own organisation, as the blank in the table above suggests. This ignorance is not obscurantist; just as law is embedded in and emerges from itself in PDIA-type reform, so Pritchett and others imagine that PDIA reformers are organised reflexively, emerging from the relationship between innovators and a social movement they seek to produce. Innovators’ innovativeness and visionaries’ visions are what tie them together in a social movement. The blank cell in the table above is not blank but redundant: the style or sensibility of PDIA is PDIA which is the global social movement.

I do not take a prescriptive position on the social edifice APW construct through PDIA. However, APW are certainly thoughtful, careful, and clear about the scope and limits of their political project. A reform sensibility-cum-reform-cum-global social network is fragile. Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff again:

[D]ifferences [between participants] in [terms of] expertise and related vocabularies persist … [G]ood-fit, situation-specific solutions to public sector problems require distributed networks of actors, both inside and outside of government, with expertise, commitment, authority, and/or resources. Effective ownership emerges from the interactions within these networks. Good-fit reform strategies explicitly acknowledge the politics, competing interests, and incentives, between and among donors and government actors. They also recognize that these interactions can build trust, which enables the translation of expertise into meaningful acceptance before a reform is adopted and implemented.Footnote 32

This is a fully fledged political image of a global social movement: it determines what decisions are amenable to ignorance (all decisions that relate to ‘public sector problems’), what sort of ignorance work is desirable (phenomenological and political – given that they imply that we are fundamentally ignorant of the full extent of the politics around those problems), and the relationship between ignorance and implementation work (ad hoc and interactional). The section I have italicised shows just how many moving parts must fall into place to build that global social movement.

***

This social movement is more than just imagined. Steps have been taken to turn it into a reality. At the level of practice and project, consider the UK government-funded ‘State Accountability and Voice Initiative’ (SAVI). Begun in 2008, and expressly developed along PDIA lines, this is a ‘£34.7 million demand-side governance programme’ managed by the British overseas development agency and operating in ten Nigerian states.

Instead of providing grant funds to CSOs (the usual way of supporting demand-side governance), SAVI works through in-house state teams [i.e. individuals and small groups already within state bureaucracies, who are disposed in favour of reform] who facilitate locally led change in their own states. They support partners to think and work politically, work adaptively and learn by doing – through brokering working relationships, and providing behind-the-scenes mentoring, capacity building and seed funding support.Footnote 33

Of note are the explicitly political aspects of SAVI’s design and implementation:

SAVI aimed to make thinking and acting politically central to decisions taken by front line staff and partners […] Staff and partners analysed the power relations that shaped change in their state, regularly updated this knowledge formally and informally, and used it to inform their decision-making. This included decisions made by SAVI state teams relating to the issues and processes they engaged with, and the alliances and partnerships they helped to facilitate.Footnote 34

SAVI thus purportedly rejects specific ideas about what good governance looks like and rejects international development expertise as a specific site for their determination. Instead, it focuses instead on political agency and conditions on the ground – Brinkerhoff and Brinkerhoff’s ‘distributed networks of actors, both inside and outside of government, with expertise, commitment, authority, and/or resources’ – in pursuit of some sort of reform. Failure, in turn, is evidence of the maladaptation of the reform effort to a complex local political environment – to be rectified in any subsequent iteration.

This ongoing reiteration of institutional change is thus enabled by a particular ignorance claim, about the complexity of local politics. This, in turn, shapes the ongoing reconfiguration of the spatio-temporality of reform and the identity of its participants. Take the UK-funded and PDIA-influenced Pyoe Pin programme in Myanmar. It focuses on ‘sub-national (local) governance and accountability’.Footnote 35 The programme works on these institutional matters across the ‘economy (fisheries, garments), natural resources (extractive industries, land, sustainable forest management) and services (education, HIV, Maternal and Neonatal Child Health)’.Footnote 36 It is so wide-ranging because it ‘brings together “coalitions” of groups and individuals’ and shifts these coalitions over time in ‘a cycle of continuous iteration’. This is acknowledged as an explicitly political endeavour in response to ‘Myanmar[’s] context[, which] is volatile, with unpredictable and uneven economic, political and social change events and opportunities presenting over time and space’.Footnote 37

Note that ignorance is expressed through the language of political participation and thus unfolds through processes of identifying stakeholders and convening them. This then has political effects. The project cobbles together politically fragile and provisional collectives, who in turn imagine fragile and provisional institutions to govern them, which in turn require new collectives to be cobbled together. In other words, the project continually provisionalises who is governing (and on behalf of whom), what is being governed, and where and when governance takes place. It unsettles the boundaries between law and politics, or what is politically settled in this regard, and what is up for political contestation. At the same time, it produces that boundary as an effect of ignorance about political participation, reminding us that PDIA’s global social movement tries to socialise political ignorance work in its participants.Footnote 38

To clarify the stakes of this, consider a hypothetical and different engagement with Myanmar, one that is expressed epistemically, in the vein of demanding ever-more research into Myanmar’s complex context. That might lead to a vision of rule of law reform as continually unfolding through a research process. This process has a spatio-temporality (e.g., ‘field sites’ and ‘field trips’) and produces participants in reform as research participants. The provisionality of the rule of law and its relationship to politics might then emerge as an effect of ongoing political contestations over the necessary constellation of research methods and practices to render that context comprehensible enough for an institutional reform.Footnote 39

***

I now turn to the programmatic level to think about the effects of the social organisation of reformers on their place in the broader development enterprise. I turn to terms of reference (ToRs) to hire rule of law reformers. They do not necessarily determine who is eventually hired; however, they are public statements by development institutions about a desired reform sensibility. Here, I conduct a brief examination of statements about ‘expertise, commitment, authority, and/or resources’Footnote 40 in UK government ToRs. The various arms of the UK government have been early adopters of and big spenders on approaches to reform such as PDIA.Footnote 41 They have a standard set of ToRs that they use for every rule of law post, setting out the required competencies and characteristics that successful candidates must have. These are publicly available online, and my analysis is based on a close reading of them.

According to their 2016 ‘Technical Competency Framework: Governance Cadre’,Footnote 42 DfID recruited ‘Security, Justice, and Human Rights’ (SJHR) specialists as part of its cadre of ‘governance advisers’. In their standardised competency framework, the list of competencies for non-SJHR governance specialists begins with clear statements of the specialty’s content: ‘[c]ore governance concepts (capacity, accountability, responsiveness, legitimacy, empowerment, rights)’; ‘Elections, parliaments, political parties, civil society and media’; ‘public sector budget cycle from formulation to execution … public procurement, internal control, reporting and accounting systems’; ‘[d]ifferent types of corruption (grand; petty; bribery; fraud; money laundering etc.)’; and so on.

The list of competencies for SJHR specialists, however, begins with no such assertion of the form or content of the rule of law. The competencies simply require that candidates have ‘knowledge’ of how rule of law ‘contribute[s] to development, stability, and state-building’. It then proceeds to connect the rule of law to a series of sectors in which reformers might wish to establish administrative facts: the rule of law’s links to ‘promoting, realising and protecting human rights’; its relationship to ‘community security, preventing gender-based violence, and security sector reform’; ‘rule of law for growth and investment, including[…] protection of property rights’; and so on. The role of the reformer is to straddle these sectors as well as all the ‘different security and justice institutions including the judiciary, prosecution, police, military, intelligence, prisons, oversight institutions, legal profession, civil society and non-state actors’; and the ‘different legal systems, including non-state justice systems, in a range of contexts, including fragile states’. Reformers are required to encompass a range of differences.

The British government also hires rule of law reformers in its Stabilisation Unit (SU), a special cadre of aid professionals working in fragile states. The competencies for an SU specialist on ‘justice’ and ‘community safety, security and access to justice’ again stress difference.Footnote 43 They open with statements on the complexity of the rule of law. Moving to a technical level, the ‘justice’ competencies then require reformers to understand how to work with a ‘range of different justice systems, often characterised by legal pluralism’Footnote 44 and have experience in ‘holistic approaches to justice sector reform, including cross-sectoral linkages, interdependence and the role of non-state actors in justice delivery’.Footnote 45 The ‘local security and justice’ competencies require candidates to have a good working knowledge of the universe of ‘[n]on-state, community based and traditional security and justice actors and mechanisms’ as well as ‘the relationships between the state and non-state security and justice actors and mechanisms’.Footnote 46

Both documents also specify behavioural competencies. However, the SU document explicitly links behavioural and technical components: various reformers are required to bring to their job the ability to ‘manag[e] and understand[] politically sensitive situations’ and ‘adapt[] to different social and cultural environments’.Footnote 47

Stepping back, the ToRs articulate a style for reformers: ambivalence. The ToRs are ambivalent towards the type of ignorance work that matters. Ignorance work might emerge from reformers’ professional experience with the complexities of the rule of law, or it might simply come from the complexity of the social and cultural environment. They are also ambivalent towards the relationship between ignorance and implementation work: ‘manag[ing] and understand[ing]’ politics is much less specific than ‘responding’ to context or ‘resolving’ real problems. Ignorance is broadly distributed.

This ambivalence is not cabined by a political or institutional context, in contrast to PDIA, which imagines its global social movement as helping reformers navigate those contexts. Indeed, it is also in contrast to ToRs in the same documents but for other governance domains. For example, the ToRs for public financial management require candidates to know how to work with ‘International Financial Institutions (World Bank, IMF) and international PFM initiatives and frameworks, for example PEFA, the Open Budget Partnership, and INTOSA’, and thus imagine them as part of a network of institutions, initiatives, and frameworks.Footnote 48

Instead, rule of law reformers are relatively formless. In their ToRs, there is no reference to any global social movement or distributed networks of actors. Each reformer is left to work out what to do about the rule of law in whatever context they work. These ambivalent reformers instead sit within their departments, working on building their own ‘cross-sectoral linkages’ (as in the SU ToRs for rule of law reform) and reaching out to a range of different institutions (as in the SJHR ToRs).

The ToRs remind us that the politics of social organisation is not just an effort to regulate a reformer’s style or sensibility. It is also an outwards-facing effort to manage the relationship between rule of law reformers and development practice more broadly. Returning to the ADA project, my team resembled the rule of law reformers imagined in the ToRs: a group of holistic and complexity-sensitive individuals sitting in a department and working with colleagues. Recall that the agricultural economist who sparked our ADA work had a project whose fiscal and economic principles he proclaimed were sound, but whose major ‘problem’ he proclaimed was ‘politics’. Our role was to deal with the complex dimensions of his project. We functioned as a receptacle for ‘politics’, which we then deposited in the highly elastic and eternally contestable form of the ADA. In effect, our professional role was to purify his truth claim by bracketing and containing its conditions of failure. This role was structured by our position in the DA. Without an alternative form of social organisation for our ignorance, we accepted the DA’s categorisation of particular questions as more, or less, suffused with ignorance. Had we been within PDIA’s global social movement, however, we may have had the vocabulary to articulate an alternative to the agricultural economist – for example, to politicise other dimensions of his project.

I am arguing here that the social form given to expert ignorance shapes its relationship to other expert regimes in development. The form frames and channels political energy that might contest the institutions that rule of law reform generates. For example, it raises the possibility that people might have a meaningful impact on institutions – indeed, it raises key first-order questions about the values and politics of institutions and invites people to contest them. Yet it does not necessarily offer a means of resolving these questions, and while people are stuck debating them, important second-order issues might get resolved by more authoritative adjacent expert domains. In other words, so organised, rule of law reforms might have a depoliticising effect precisely by appearing to be deeply political endeavours.

7.3 Conclusion

In this chapter, I have argued that if reform is the structure of theatrical action, then people and institutions might try to organise it socially and thus regulate that action – from disciplining it within an institution like the World Bank to organising it through a global social movement such as PDIA. The politics of these efforts are found as they categorise decisions as more or less amenable to ignorance and implementation work, and in doing so, they express preferred types of, and relationships between, ignorance and implementation work.

I have also drawn attention to two sets of effects that result from this politics. First, it shapes the forms of the rule of law that reforms produce. Second, it shapes the place of reformers within the broader development enterprise. At one end, a reformer may operate alone in her silo, unable to develop links to other practitioners in the absence of any meaningful core to her expertise. At the other, she may offer the promise of wide-ranging impact as well as an opportunity for other forms of development rationality – development microeconomics, Weberian institutionalism, formal legalism, and so on – to purify themselves by jettisoning their political and socially contextual challenges.