Non-fatal self-harm is an important public health problem in England. In 2000–2001 there were an estimated 220 000 presentations to general hospital emergency departments involving 150 000 people. Reference Hawton, Bergen, Casey, Simkin, Palmer and Cooper1 Self-harm is the main risk factor for completed suicide Reference Owens, Horrocks and House2,Reference Cooper, Kapur, Webb, Lawlor, Guthrie and Mackway-Jones3 and is associated with increased all-cause mortality. Reference Hawton, Harriss and Zahl4 In England, the National Suicide Prevention Strategy 5 has a target of a 20% reduction in rates of suicide (including open verdicts) by 2010. 6 One of the high-risk groups targeted in the strategy is people who self-harm. There is no national register of self-harm, and reported trends in self-harm to date have been from periods before the strategy was introduced in 2002. Reference Schmidtke, Bille-Brahe, De Leo and Kerkhof7–Reference Wilkinson, Taylor, Templeton, Mistral, Salter and Bennett13 During 1990 to 1997, rates of self-harm increased in some centres in England, Reference Belgamwar, Hodgson and Waters8–Reference O'Loughlin and Sherwood10 as well as rates of repetition and alcohol involvement, Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hall, Simkin, Bale and Bond9,Reference O'Loughlin and Sherwood10 implying increasing pressure on emergency and hospital services. Health service planning requires up-to-date information on trends in self-harm to maintain an optimal provision of services, and to assess the effectiveness of management and preventive policies. Most reports of trends in self-harm in the UK have come from single centres. We know of one study relating rates of self-harm to suicide in the USA. Reference Claassen, Carmody, Bossarte, Trivedi, Elliott and Currier14

The aim of this study was to investigate trends in non-fatal self-harm in multiple centres between 2000 and 2007, and to relate these to trends in suicide. During this period a national suicide prevention strategy was introduced for England. Specifically, we looked at trends in rates of self-harm, methods of self-harm, alcohol involvement and repetition of self-harm in six hospitals in three centres in England.

Method

Setting and sample

The study was undertaken in three centres currently involved in the Multicentre Study of Self-harm in England (for further details see Hawton et al Reference Hawton, Bergen, Casey, Simkin, Palmer and Cooper1 and Bergen et al Reference Bergen, Hawton, Murphy, Cooper, Kapur and Stalker15 ). Data were collected on all individuals who presented with self-harm to general hospital emergency departments in Oxford (one), Manchester (three) and Derby (two) for the 8-year period 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2007. Self-harm was defined as intentional self-poisoning or self-injury, irrespective of motivation. Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hall, Simkin, Bale and Bond9

Data collection

Following self-harm, most individuals received a psychosocial assessment (of mental state, risks and needs) by specialist psychiatric clinicians (and in Manchester also by emergency department staff), Reference Kapur, Murphy, Cooper, Bergen, Hawton and Simkin16 in line with clinical guidance. 17,18 Demographic, clinical and hospital management data on each episode were collected by clinicians using forms, in Oxford and Manchester. In Derby, data were entered directly into a computerised system by clinicians. Individuals not receiving an assessment were identified through scrutiny of emergency department and medical records (computerised records in Derby), from which more limited data were extracted by research clerks. In all centres, individuals not assessed may have taken early discharge, refused the offer or not been offered an assessment for clinical reasons or unavailability of staff.

In Manchester, for the period 1 January 2000 to 31 August 2002, information was collected only on assessed episodes. Information was not collected on episodes that were not assessed (including those episodes in which individuals did not wait for treatment). The proportion of the total number of episodes that were found to have been assessed in a subsequent period (1 September 2002 to 31 August 2003) was 70%. Rates of self-harm for this centre for the earlier period were therefore adjusted upwards by a factor of 1.42 to take account of the 30% of non-assessed individuals. Rates of assessment were similar by age and gender and the adjustment was applied across all age and gender groups.

Data for this study included gender, age, date of self-harm, method of self-harm (including drugs used in self-poisoning and details of self-injury), alcohol involvement and psychosocial assessment.

Ethical approval

The monitoring systems in Oxford and Derby have approval from local health/psychiatric research ethics committees to collect data on self-harm for local and multicentre projects. Self-harm monitoring in Manchester is part of a clinical audit system, and has been ratified by the local research ethics committee. All three monitoring systems are fully compliant with the Data Protection Act of 1998. All centres have approval under Section 251 of the National Health Service (NHS) Act 2006 (formerly Section 60, Health and Social Care Act 2001) to collect patient-identifiable information without patient consent.

Rates of self-harm

Rates of self-harm were calculated for defined population areas within centre catchments (Oxford City, City of Manchester and Derby Unitary Area) for which centres had near to complete identification of self-harm presentations to hospital. Mid-year population estimates were obtained from the Office for National Statistics. 19 Rates were calculated as the number of people (aged 15+) per 100 000 population for each centre, for each year, age standardised to the European population, with 95% confidence intervals based on a Poisson distribution. The 95% confidence intervals for average rates (2000–2007) were estimated using an approximation of the standard error (rate divided by the square root of the number of people) multiplied by 1.96.

Rates of suicide

Rates of suicide in England (age standardised to the European population) were obtained from the NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. 20 Data for individuals of all ages included deaths where the coroner had given a suicide or open verdict.

Socioeconomic indicators

Socioeconomic conditions of the areas covered by the three centres were compared using Multiple Indices of Deprivation 2004 in England, 21 which ranks areas from 1 (most deprived) to 32 482 (least deprived) over 7 domains (income, employment, health deprivation and disability, education skills and training, barriers to housing and services, crime, living environment). The mean rank over all domains for the City of Manchester was 4268 (within the 15% most deprived areas), compared with Derby Unitary Area 13 329 (within the 40% most deprived), and Oxford City 15 953 (approximately midway). On the income and employment domains, Manchester was within the 20% most deprived, compared with Derby (within the 40% most deprived) and Oxford (within the 45%–35% least deprived).

Statistical analyses

Rates of self-harm and trends in rates were calculated separately for each centre. Rates for Manchester were adjusted for the period with missing data (1 January 2000 to 31 August 2002). Also, because of these missing data, trends in method of self-harm and repetition were analysed using data from two centres only (Oxford and Derby) for the years 2000–2002, and from the three centres for 2003–2007, because these variables were, to a certain extent, related to assessment status.

The χ2-test for trend (linear by linear association, two-sided) was used to test the significance of changes over the period 2000–2007. There was no significant autocorrelation in data tested for trend. Best-fit values from linear regression models were used to calculate percentage changes over time. Analyses and calculations were performed with Microsoft Office Excel 2003, SPSS version 15.0, Stata version 10.0 and Epi Info 2002 on Windows XP.

Results

Study sample

During the 8-year study period, 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2007, there were 51 206 episodes of self-harm by 31 278 individuals aged 7+ years across the three centres (Table 1).

Table 1 Number of episodes of self-harm and individuals involved, by centre, 2000 to 2007

| n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford | Manchester | Derby | Total | |

| Episodes | 13 102 | 22 985 | 15 119a | 51 185a |

| Males | 4889 (37.3) | 9481 (41.2) | 6113 (40.5) | 20 483 (40.0) |

| Females | 8213 (62.7) | 13 504 (58.8) | 8985 (59.5) | 30 702 (60.0) |

| Individuals | 7394 | 15 293 | 8591a | 31 260b |

| Males | 2973 (40.2) | 6459 (42.2) | 3599 (42.0) | 13 031 (41.7) |

| Females | 4421 (59.8) | 8834 (57.8) | 4974 (58.0) | 18 229 (58.3) |

| Males by age group, years | 2968 | 6402 | 3593 | 12 963c |

| Under 15 | 43 (1.4) | 66 (1.0) | 50 (1.4) | 159 (1.2) |

| 15–24 | 970 (32.7) | 1891 (29.5) | 1058 (29.4) | 3919 (30.2) |

| 25–34 | 787 (26.5) | 1803 (28.2) | 968 (26.9) | 3558 (27.4) |

| 35–54 | 937 (31.6) | 2251 (35.2) | 1234 (34.3) | 4422 (34.1) |

| 55+ | 231 (7.8) | 391 (6.1) | 283 (7.9) | 905 (7.0) |

| Females by age group, years | 4419 | 8790 | 4969 | 18 178d |

| Under 15 | 250 (5.7) | 283 (3.2) | 243 (4.9) | 776 (4.3) |

| 5–24 | 1819 (41.2) | 3575 (40.7) | 1868 (37.6) | 7262 (39.9) |

| 25–34 | 888 (20.1) | 1991 (22.7) | 1082 (21.8) | 3961 (21.8) |

| 35–54 | 1180 (26.7) | 2497 (28.4) | 1444 (29.1) | 5121 (28.2) |

| 55+ | 282 (6.4) | 444 (5.1) | 332 (6.7) | 1058 (5.8) |

Age and gender were known for 31 141 individuals (0.4%, n = 137 were missing) (Table 1). The median age for males was 31 years (interquartile range, IQR 22–41), and for females was 27 years (IQR 19–39). Nearly two-thirds of individuals (n = 19 646, 63.1%) were under 35 years. When examined by 5-year age groups, the largest number of females was in the 15–19 age group (n = 4042, 22.2%), and the largest number of males was in the 20–24 age group (n = 2279, 17.6%).

Rates of self-harm

Age-standardised rates per 100 000 (95% CI) for individuals aged 15+, averaged over the years 2000–2007, were: Oxford, males 310 (95% CI 294–325), females 412 (95% CI 395–429); Manchester, males 371 (95% CI 361–381), females 544 (95% CI 533–556); Derby, males 373 (95% CI 359–387), females, 510 (95% CI 494–527) (online Table DS1). Rates for both males and females were significantly lower in Oxford than the other centres, whose rates were similar. The female to male ratio of the mean annual rate of self-harm (2000–2007) for individuals aged 15+ years, averaged over the three centres, was 1.38. Annual rates for the three centres are presented in online Table DS1 and Fig. 1, together with rates of suicide in England. Both rates of self-harm and suicide declined over the period 2000–2007 (Fig.1).

For all individuals, significant decreasing trends in rates of self-harm were found in two centres only. In Manchester, the decrease from 2000 to 2007 was 21% (χ2 for trend: 33.0, P<0.001) and in Derby it was 15% (χ2 for trend: 15.5, P<0.001). In Oxford, the decrease was 8% (χ2 for trend: 2.9, P = 0.088). Overall (three centres), the percentage decrease was 18% (χ2 for trend: 21.4, P<0.001). The decrease in the suicide rate in England during this period was approximately 19%. 20

For males, significant decreasing trends in rates of self-harm were found in all centres. In Oxford, the decrease from 2000 to 2007 was 14% (χ2 for trend: 4.5, P = 0.034), in Manchester it was 25% (χ2 for trend: 19.8, P<0.001) and in Derby it was 18% (χ2 for trend: 8.9, P = 0.003). Overall (all three centres), the percentage decrease was 21% (χ2 for trend: 13.8, P = 0.0002). The decrease in the suicide rate in England for males during this period was approximately 18%. 20

For females, significant decreasing trends in rates of self-harm were found in two centres only. In Manchester, the decrease from 2000 to 2007 was 17% (χ2 for trend: 12.8, P<0.001) and Derby 13% (χ2 for trend: 6.4, P = 0.011). In Oxford, the decrease was 2% (χ2 for trend: 0.1, P = 0.722). Overall (all three centres), the percentage decrease was 14% (χ2 for trend: 7.7, P = 0.005). The decrease in the suicide rate in England for females during this period was approximately 25%. 20

In Manchester, decreasing trends in rates of self-harm remained significant when calculated over the 5-year period 2003–2007 (i.e. excluding the period with adjusted data) in males (χ2 for trend: 8.7, P = 0.003), females (χ2 for trend: 4.9, P = 0.027) and all individuals (χ2 for trend: 13.8, P<0.001).

Methods of self-harm

There were 44 495 episodes of self-harm during 2000 to 2007 (two centres, Oxford and Derby, for 2000–2002; all three centres for 2003–2007), including 165 (0.4%) where the method was not recorded. Of the 44 330 episodes with a known method, 34 695 episodes (78.3%) involved ‘self-poisoning only’ (Oxford: 77.3%; Manchester: 78.4%; Derby: 78.9%), 6503 episodes (14.7%) involved ‘cutting only’ (Oxford: 12.8%; Manchester: 16.0%; Derby: 14.9%), 1309 episodes (2.9%) involved ‘other self-injury not cutting’ (Oxford: 3.6%; Manchester: 2.3%; Derby: 3.1%) and 1818 episodes (4.1%) involved ‘both self-poisoning and self-injury’ (Oxford: 6.7%; Manchester: 3.2%; Derby: 3.1%).

Fig. 1 Trends in annual age-standardised rates of self-harm in three centres (Oxford City, City of Manchester and Derby Unitary Area) for age 15+ years, and rate of suicide (including open verdicts) in England for all ages in (a) all individuals, (b) males and (c) females.

Trends in methods of self-harm

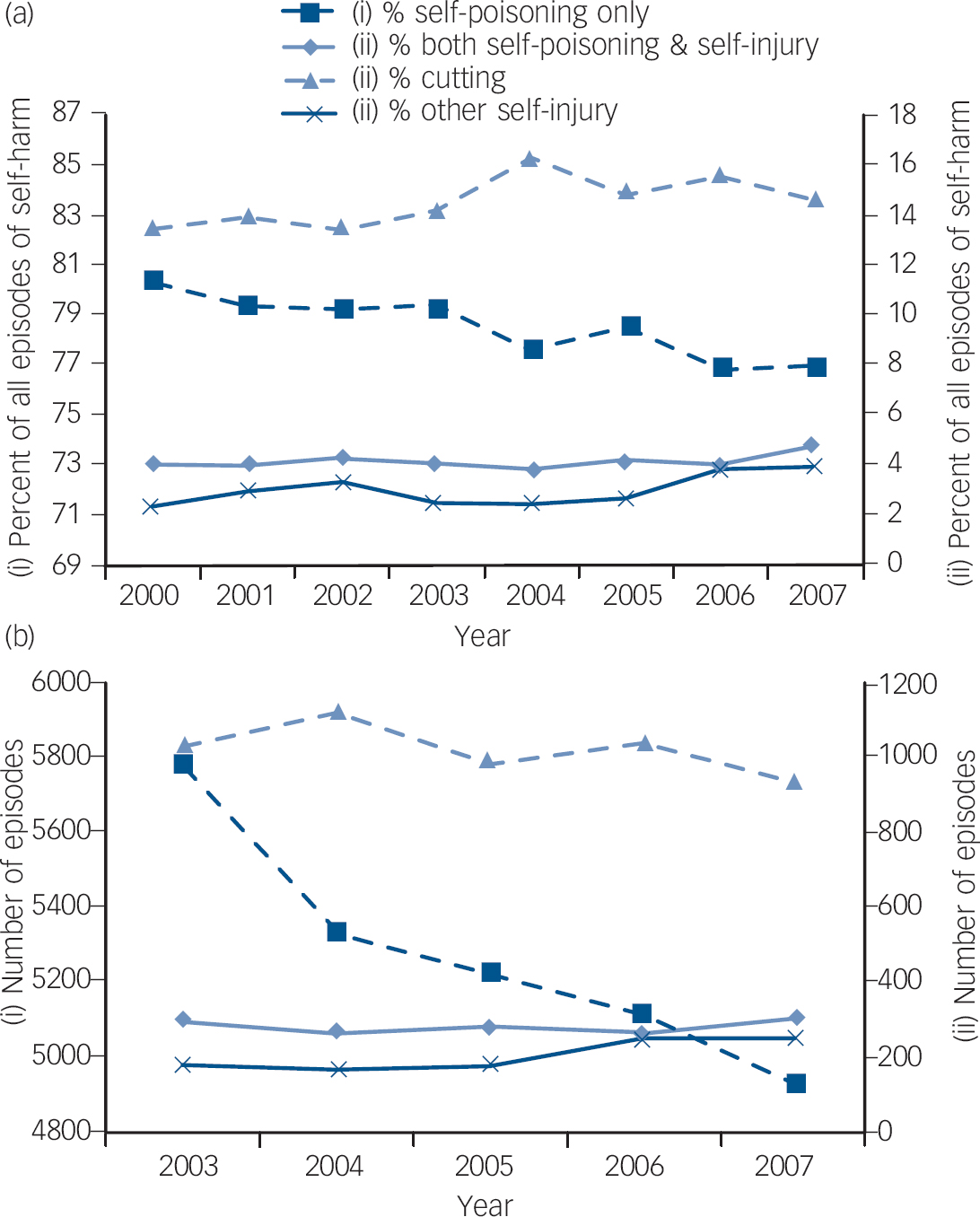

Trends in methods of self-harm are presented in Fig. 2. Figure 2a shows each method as a proportion of all self-harm for 2000–2007 and Fig. 2b shows the number of episodes by method of self-harm for 2003–2007.

‘Self-poisoning only’ as a proportion of all self-harm showed a decreasing trend during 2000 to 2007 (χ2 for trend: 27.8, P<0.001) (Fig. 2a) and the number of episodes of self-poisoning also decreased during 2003 to 2007 by approximately 15% (Fig. 2b).

‘Cutting only’ as a proportion of all self-harm during 2000 to 2007 showed a small increasing trend of 8% (χ2 for trend: 8.9, P = 0.003) (Fig. 2a). However, the number of episodes of cutting decreased by approximately 10% during 2003 to 2007 (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2 Trends in the method of self-harm (a) as a proportion of all episodes of self-harm, combined data from two centres, Oxford and Derby, 2000 to 2002, and all three centres 2003–2007, and (b) number of episodes in the three centres 2003–2007.

In contrast, ‘other self-injury only’ (including, for example, hanging, drowning, gunshot, traffic-related injury) showed an increasing trend when considered as a proportion of all self-harm during 2000 to 2007 (χ2 for trend: 22.9, P<0.001) (Fig. 2a), and the number of episodes increased by approximately 37% during 2003 to 2007 (Fig. 2b).

No significant trend was found for ‘both self-poisoning and self-injury’ as a proportion of all self-harm from 2000 to 2007 (χ2 for trend: 2.43, P = 0.119) (Fig. 2a). The number of episodes was also stable during 2003 to 2007 (Fig. 2b).

Trends in drugs used for self-poisoning

There were 36 513 episodes of self-poisoning (with or without self-injury) during 2000 to 2007, including 1320 (3.6%) episodes where the drug type was unknown. Of the 35 193 episodes with known drugs, 46.7% involved paracetamol or compounds including salicylate, 24.6% antidepressants, 14.8% benzodiazepines, 6.5% major tranquillisers and 43.1% all other drugs combined, such as antibiotics, sedatives, opiates, non-steroidal inflammatory drugs (all drugs taken were included in these data). There were no discernible trends for different drug types during 2003 to 2007.

Psychosocial assessment

There were 44 495 episodes of self-harm between 2000 and 2007 (two centres, Oxford and Derby, for 2000–2002; all three centres for 2003–2007), including 24 (0.1%) where the assessment status was unknown. The majority of people presenting with self-harm were offered a psychosocial assessment by specialist psychiatric staff, although this differed by centre due to the nature of clinical services (Oxford: 72.1%; Manchester: 41.3%; Derby: 59.2%; χ2 = 2858.2, d.f. = 2, P<0.001). In Manchester, a further 26.4% of individuals were assessed by emergency department staff. Thus between two-thirds and three-quarters of individuals who presented with self-harm in all centres had some assessment.

Alcohol involvement

Alcohol use in the 6 h before, or as part of the act of self-harm, could only be determined for people who were assessed. Of the 35 843 assessed episodes from 2000 to 2007, 2990 (8.3%) had missing information on alcohol use, thus data were available for 32 853 episodes. Overall, alcohol involvement was similar in the centres (Oxford: 54.1%; Manchester: 55.4%; Derby: 57.4%; χ2 = 18.9, d.f. = 2, P <0.001). Alcohol involvement was greater in males (62.5%) than females (50.8%) (χ2 = 437.6, P<0.001).

There were no significant trends in alcohol involvement over the study period in males (χ2 for trend: 1.1, P = 0.286) or females (χ2 for trend: 0.6, P = 0.439).

Repetition of self-harm

We used re-presentation for self-harm within 1 year of an index episode as a measure of repetition. We took individuals at their first episode in each year 2000–2006, and calculated the percentage who repeated within 1 year (two centres for 2000–2002; all three centres for 2003–2007) (n = 44 495). Overall, 20.7% of people in each year repeated self-harm within a year (Oxford: 22.6%; Manchester: 18.0%; Derby: 21.9%; χ2 = 71.3, d.f. = 2, P<0.001). There were no significant trends in repetition over the study period: Oxford, χ2 for trend: 2.37, P = 0.1; Manchester, χ2 for trend: 1.1, P = 0.298; Derby, χ2 for trend: 1.4, P = 0.239.

Discussion

In this study we investigated trends in non-fatal self-harm in six general hospitals in three centres in England during 2000 to 2007. Our main finding was that rates of self-harm declined (although less in Oxford than the other centres), in line with suicide rates in England, during a period when the national suicide prevention strategy was introduced. 5

Rates of self-harm

Overall rates of self-harm were higher in Manchester and Derby than Oxford, as expected based on greater socioeconomic deprivation in the first two areas. 21,Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hodder, Simkin and Gunnell22 The decline in rates over the 8-year period was also greater in Manchester (21%) and Derby (15%) than Oxford (8%). Across the three centres, rates for females were approximately 40% higher than for males, consistent with findings elsewhere. Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hall, Simkin, Bale and Bond9,Reference O'Loughlin and Sherwood10,Reference Hawton, Fagg, Simkin, Bale and Bond23 The decline in rates over the 8-year period, however, was greater in males (14 to 25%) than females (2 to 17%).

The trends found in this study are in contrast to the steady increase in rates of self-harm found a decade earlier. Reference Hawton, Harriss, Hall, Simkin, Bale and Bond9,Reference O'Loughlin and Sherwood10,Reference Hawton, Fagg, Simkin, Bale and Bond23 Non-fatal self-harm leading to hospital attendance is the strongest risk factor for completed suicide, Reference Owens, Horrocks and House2 and these decreasing trends are consistent with the current downward trend in suicide rates in England over this period, most of which coincided with the national suicide prevention strategy. 6,24 Suicide rates in local authority areas 20 for study centres showed a consistent decline over the study period for Manchester, whereas rates in Derby and Oxford fluctuated at lower levels. This may indicate that the reduction in suicide and self-harm has been greater in areas of greater socioeconomic deprivation. 21 The suicide prevention strategy targeted high-risk groups such as individuals who self-harm and young men. The decline in rates of self-harm in males in our study is consistent with this. Other targets of the strategy such as improved media reporting of suicide and improved clinical risk management, may also have contributed to the decline; however, they were outside the scope of our study. Another target was reduced access to lethal means, which encompasses safer prescribing of drugs. We discuss this below.

There may have been other reasons for the declining rates of suicide and self-harm that were not related to the strategy. Stable economic growth and decreasing rates of unemployment during this period 25 may have contributed, as well as changes in help-seeking behaviour such as increased use of counselling services and internet websites for self-help and support. Reference Johnson, Zastawny and Kulpa26,Reference Prasad and Owens27

Methods of self-harm

There were significant changes in methods of self-harm in the three centres during 2000 to 2007. First, a decreasing proportion and number of episodes involved self-poisoning alone. This is consistent with one of the prevention strategy's targets, and the decreasing trend in suicide deaths by poisoning in England over a similar period. 28 We found no significant change in use of particular drugs for self-poisoning. Overall, nearly half of all episodes involved paracetamol or salicylate and their compounds, most readily available over the counter.

Second, as might be expected since self-poisoning decreased, cutting alone increased as a proportion of all self-harm during 2000 to 2007. However, as with self-poisoning, the number of episodes decreased over time.

Third, in contrast to self-poisoning and cutting, the proportion and number of episodes involving other methods of self-injury (such as hanging, jumping from a height, traffic-related and drowning) increased significantly over time. These trends in non-fatal self-injury are possibly related to changing trends in suicide death by injury. For example, recent increases in suicide deaths by hanging Reference Gunnell, Bennewith, Hawton, Simkin and Kapur29 and jumping 28 may reflect an increase in attempts involving these methods, and an increase in non-fatal attempts might therefore be expected.

Involvement of alcohol

The finding that alcohol involvement in episodes of self-harm remained stable for males and females during the study period is somewhat surprising, as hazardous drinking in the general population, especially in women, 30 and hospital admissions for alcohol-related conditions and deaths from alcohol-related causes 31 both increased during this time. Further, alcohol involvement in self-harm increased in line with general population trends during an earlier period. Reference Haw, Hawton, Casey, Bale and Shepherd32 One explanation may be that our analysis was limited to assessed episodes (and assessment is less likely for individuals under the influence of alcohol). Reference Bennewith, Peters, Hawton, House and Gunnell33

Repetition of self-harm

The proportion of people re-presenting with a repeat episode of self-harm within 1 year was unchanged. Thus although the total number of episodes and individuals involved decreased over time, those individuals who self-harmed continued to re-present with approximately the same frequency. Assessment and referral for further care can reduce repetition rates. Reference Bergen, Hawton, Waters, Cooper and Kapur34,Reference Crawford and Wessely35 However, since the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidance on the management of self-harm 17 was introduced midway through the study period, its impact may have been limited as the centre hospitals already had dedicated clinical services for self-harm in place throughout the study period and had high assessment rates compared with other hospitals. Reference Bennewith, Gunnell, Peters, Hawton and House36

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the study was the involvement of three centres covering six general hospitals that enabled comparison of findings between centres (e.g. rates), as well as analysis of pooled data (over 50 000 episodes), with sufficient statistical power to detect trends not normally possible in single-centre analyses. Although the centres may not be representative of England as a whole, their catchment populations were varied and included individuals from a wide range of sociodemographic backgrounds. Trends in the three centres were remarkably similar, as were the characteristics of the individuals who presented such as preference for method, alcohol involvement and rate of repetition. This suggests that these findings may have broad generalisability. Differences between centres were largely in clinical management (e.g. rates of assessment and referral for psychiatric aftercare), and these will be explored in a future study.

A limitation of the study was use of the smaller sample (two centres 2000–2007, three centres 2003–2007) when analysing trends where data were related to assessment status, e.g. method of self-harm. During 2003 to 2007, only half of all self-cutting episodes were assessed compared with two-thirds to three-quarters of other methods, so inclusion of 2000–2002 data (available for assessed episodes only) would have influenced trend analyses by incorrectly inflating proportions of other methods in those years.

A further limitation is that there were no major changes in services or prevention activities related to the strategy targeting individuals who self-harm in the study centres, so it is difficult to attribute a direct causal link between them and reduced rates of self-harm. Likewise, although adverse socioeconomic conditions are known to be strongly associated with self-harm, and some local studies have been done in the past, Reference Hawton, Harriss, Simkin, Bale and Bond37,Reference Johnston, Cooper, Webb and Kapur38 we have not been able to analyse socioeconomic changes in study centres over the study period.

Implications

Our findings provide important information on community psychosocial health, with implications for acute and mental health service management and suicide prevention policy. 5 The decline in rates of self-harm implies a lessening burden on hospital emergency services during the study period. Decreasing trends in the number of individuals who presented with self-poisoning and self-cutting, and increasing trends for those who presented with other more serious injury, such as hanging, may be related to changing individual characteristics, and may also have reflected changes in preferred methods of suicide at a national level.

Self-harm leading to hospital attendance is the strongest risk factor for death by suicide. Rates of self-harm can serve as a measure of effectiveness of suicide prevention strategies since the larger numbers involved imply a greater sensitivity to detect change. Our findings suggest that prevention initiatives undertaken in England since the introduction of the national strategy in 2002, 5 probably together with favourable societal factors, may have had a positive impact in reducing both self-harm and suicide. However, socioeconomic conditions in the UK have since deteriorated. Assessment of the impact of the recent recession and the associated rise in unemployment, both of which are known risk factors for self-harm and suicide, are important topics for future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors from Oxford thank Deborah Casey, Elizabeth Bale and Anna Shepherd and members of the general hospital psychiatric services for their assistance with data collection. The authors from Manchester thank the clinicians completing assessment forms and the research team for their data collection, Elizabeth Murphy, Iain Donaldson, Maria Healey and Stella Dickson. The author from Derby thanks Carol Stalker and the clinicians, clerical and administrative staff in the emergency department and mental health liaison team.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.