1. Introduction

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit Italy and Europe, long-standing social problems came to the surface, and among these was that of migrant farmworkers.Footnote 1 Because their work is necessary to guarantee fruit and vegetable supply, they have been labelled ‘essential workers’: employees in the health, transport, and food sectors that perform services vital for the rest of society and thus must continue working despite the risk of infection. It was then impossible to ignore that many of those essential workers are also generally placed at the bottom of the social ladder: people at the margins, poorly paid, potentially more exposed to Covid-19 infections, and often coming from abroad.Footnote 2

Indeed, in the last decades, European countries have increasingly relied on foreign workers to perform labour in the agriculture sector. Especially countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Italy are increasingly dependent on hundreds of thousands of migrant seasonal workers recruited during the harvesting season every year. And this is a growing trend in the EU: national workers abandon the fields and get partially replaced by EU and third-country national (TCN) workers.Footnote 3

During the pandemic, the inflow of migrant workers was disrupted. This was mainly caused by the closure of the EU external and internal borders, which suspended free movement and impeded TCN workers to reach Europe, leading farmers to denounce the risk of seasonal labour shortages.Footnote 4 In Italy and Germany, farmers raised the alarm that the absence of workers from abroad would put agricultural production in danger.Footnote 5 In the UK, King Charles III (then Prince) and the Secretary of State for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs launched the ‘Pick for Britain’ campaign, urging British people to harvest fruits and vegetables to avoid the growing crops going to waste.Footnote 6

At the same time, trade union organisations denounced the dangers that farmworkers were facing during the pandemic.Footnote 7 Their precarious and exploitative working conditions often translated into more exposure to health risks: overcrowded housing and the impossibility to keep social distance while working in the field increased farm workers’ chances of getting infected. The European Trade Union Federation denounced the situation of undocumented seasonal migrants in Italy, which ‘is particularly critical in this emergency period, with thousands of them living segregated in deplorable housing, shantytowns (called “ghettos”) often without running water and electricity and with poor sanitary conditions, in which they live for fear of being discovered and [receiving] an expulsion decree’.Footnote 8

This paper focuses on TCN migrant farmworkers in Italy and investigates the role of EU law, and in particular the Seasonal Workers Directive, in this context. Over the last 20 years, Italy has seen a huge increase in migrant farmworkers;Footnote 9 according to official data, in 2020, 32.1 per cent of farm employees were non-Italians; of these, 62.2 per cent were from a country which is not part of the EU.Footnote 10 But Italy is also notoriously famous for the exploitation of migrant workers in the agricultural sector, which has been denounced by both national and international monitoring bodies.Footnote 11 In this difficult context, did the Seasonal Workers Directive help provide adequate protection and working conditions to migrant farmworkers? Did it achieve its goal of facilitating farmers’ efforts to recruit workers from abroad?

This article develops as follows: first, it gives an overview of the content of the Directive, highlighting the different tensions at play during the negotiation process: while the Commission wanted it to be an instrument to facilitate the import of temporary labour, the EU and national parliaments raised concerns regarding the fair and equitable treatment of workers. Section 3 then moves to the Italian context to assess the Directive’s actual impact on the composition of the workforce: it examines whether the Directive has increased employers’ capacity to recruit cheap labour from abroad. Section 4 then analyses whether the Directive has facilitated circular migration and enhanced workers’ social protection, drawing on data and reports on Italy in the period preceding and during the pandemic. Finally, the paper draws some conclusions on the EU Seasonal Workers Directive, arguing that it suffers from systemic deficiencies deriving from it being constructed upon false or fragile premises. As the paper will show, the Directive was almost irrelevant to regulate and protect the situation of seasonal migrant farmworkers during the pandemic.

2. The EU seasonal workers directive

Labour migration is an uneasy terrain for the EU. Article 79 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) gives competence to the EU to legislate over migration from third countries, but it also reserves the right of Member States to decide the number of migrant workers to be admitted to their territories.Footnote 12 As a result, over the years, the European Commission tried to harmonise the conditions for entry and residence of selected categories of migrant workers, without affecting the volumes of admissions. The regulated categories are high-skilled workers,Footnote 13 single permit workers,Footnote 14 intra-corporate transferees,Footnote 15 and seasonal workers.Footnote 16

The most relevant legal instrument to analyse the situation of farmworkers is the Seasonal Workers Directive. Agriculture is considered one of the sectors of employment structurally characterised by the seasonality of work: because the cycle of production depends upon and follows closely the passing of the seasons, farmers’ demand for workers is expected to increase and decrease according to seasons too. Although the technological transformation of the sector meant that seasons are not as important as in the past, still a huge portion of employment in agriculture is characterised by short-term or seasonal contracts. And a significant percentage of these seasonal workers are migrants, either from the EU or from non-EU countries.

The Seasonal Workers Directive was expressly introduced to promote temporary and circular migration.Footnote 17 This can be considered a lesson learned from the experience with ‘guest workers’ of countries like Germany and the Netherlands after World War II: to fill in labour shortages, these countries introduced programs to attract workers from countries such as Turkey and Morocco that then settled in and became permanent residents, generating some uneasiness with the host societies.Footnote 18 The idea behind the Seasonal Workers Directive is different: it would avoid increasing the immigrant population in the EU by facilitating only temporary migration (the seasonal worker permit lasts a maximum of nine months).Footnote 19 When employers will no longer need these foreign workers, they will return to their state of origin and possibly be called for the next harvesting season.Footnote 20

The Seasonal Workers Directive introduced a uniform and ad hoc residence permit for TCN migrant workers with two different goals. First, such a residence permit would facilitate temporary migration to respond to employers’ needs for prompt and flexible seasonal labour. Second, it aims to grant seasonal workers decent working and living conditions by providing fair and transparent rules for admission and by giving them equal treatment rights.Footnote 21 This twofold goal reflects the tensions in the negotiation process, where the Commission stressed the need to supply unmet labour demands, while the national and EU parliaments showed concerns over seasonal workers’ treatment;Footnote 22 eventually, the negotiation rendered the Directive a hybrid instrument of immigration control and labour protection, with evident tensions at play.Footnote 23

The Directive states the conditions for the admission of seasonal workers. When applying, migrants must reside outside the Union and show they possess a series of requirements among which: a job contract or a binding job offer, sufficient resources during their stay, evidence of adequate accommodation and of having applied for sickness insurance.Footnote 24 The Directive also provides for the maximum duration of the seasonal worker permit, which the Member States can set between five and nine months, after which the workers must leave the territory of the Member State unless they obtain a different residence permit.Footnote 25

Probably the most protective provision of the Seasonal Workers Directive is Article 23, on the right to equal treatment. This grants TCN workers the right to be treated equally to Member State’s citizens in selected fields such as the terms of employment, the right to strike and take industrial action, and the branches of social security indicated under Article 3 of Regulation 883/2004.Footnote 26 According to a well-established interpretation of this Regulation by the Court of Justice, social security benefits are those which are granted ‘automatically on the basis of objective criteria, without any individual or discretionary evaluation of personal needs’.Footnote 27 Still, during the negotiations, the Member States obtained the possibility to exclude TCN seasonal workers from unemployment and family benefits,Footnote 28 and this is indeed what the Italian legal framework provides.Footnote 29

It was especially this comprehensive equal treatment provision that prompted trade unions and commentators to be cautiously optimistic about the Seasonal Workers Directive. The European Federation of Food, Agriculture and Tourism Trade Unions (EFFAT) welcomed the provisions on equal treatment and considered the Directive as a potential improvement for migrant seasonal workers’ conditions.Footnote 30 At the same time, EFFAT also warned that the Directive ‘partially overlooks the current situation’ where ‘there is a strong presence of third-country seasonal workers with irregular migration status already employed under very precarious conditions’ and ‘considers the non-extension of the scope of the directive to third-country nationals already residing in EU Member States as a lack of commitment and ambition by the EU Institutions’.Footnote 31 This article will show that EFFAT criticisms were to the point.

3. Is the seasonal worker permit a ‘flexible response to employers’ actual workforce needs’?

As mentioned, one of the goals of the Seasonal Workers Directive was to give employers the possibility, when they need workers, to promptly recruit cheap labour from countries outside the EU.Footnote 32 According to the Impact Assessment of the European Commission, the EU Directive’s added value consists in providing ‘a flexible admission system to cope with seasonal labour shortages’.Footnote 33

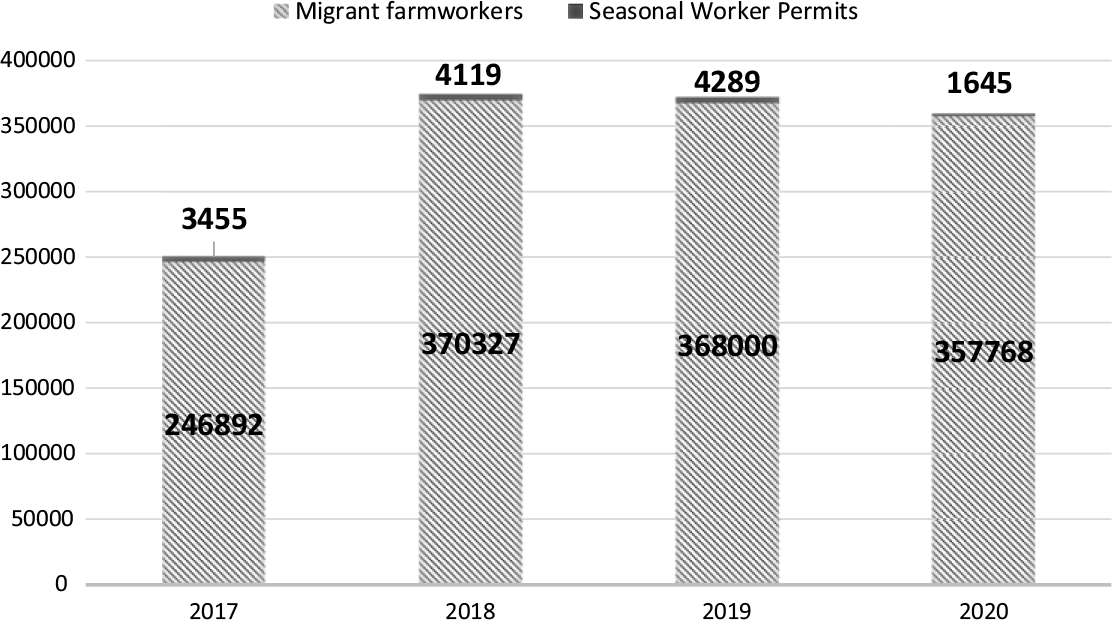

However, when looking at data on the number of seasonal worker permits issued by Italy since the transposition of the Directive in 2016,Footnote 34 one would notice the numbers are extremely low. As Figure 1 shows, the number of seasonal worker permits issued in 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020 go from a minimum of 1,645 to a maximum of 4,289 per year. These numbers are already very low if considered by themselves, but they will appear almost irrelevant if compared to the total number of migrant farmworkers (EU and TCN) present in Italy during the same years, which goes from about 250,000 to more than 350,000 per year (of these, around 60 per cent are TCN migrants).Footnote 35 In sum, we can quite confidently say that the migrants holding a seasonal worker permit, and therefore recruited through the system set up by the EU Directive, amount to a very small fraction of the total of migrant farmworkers.

Figure 1. The number of seasonal worker permits issued every year (in dark grey) vs the total number of migrant farmworkers (in light grey).

One may think that the reason behind such limited use of the seasonal worker permits lies in the fact that the Directive only regulates the admission criteria and the legal status of TCN migrants but leaves it to the Member States, and in this case Italy, to decide how many migrants to eventually admit. This is only partially true. Indeed, every year the Italian lawmaker issues the so-called ‘Decreto Flussi’ which states the maximum number of visas available for each visa category (like a quota system).Footnote 36 However, the number of visas available is much higher than the number eventually issued: for 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, the quota set by the Italian government for seasonal work was 17,000 or 18,000 per year, but only a few thousand were eventually activated.Footnote 37

Rather, the reason behind the limited use of the Seasonal Workers Directive should be sought elsewhere. Arguably, the Directive is unsuitable for how labour demand and supply meet in the Italian agricultural sector. The Directive’s procedure for recruiting workers from abroad entails a long and cumbersome administrative process, where a farmer in Italy should stipulate a job contract with a worker residing abroad who then applies for a visa showing possession of all relevant economic and legal requirements; this is very far from being ‘prompt’ or ‘flexible’ and it is often at odds with the immediate need for workers that characterises some sectors of agricultural production. Structural characteristics of the agricultural sector, such as the indeterminacy of the harvesting periods and of the amount of production, or the highly unpredictable weather conditions, contribute to quickly creating or dissolving demand for farmworkers. Meeting such a volatile demand with a long procedure to import labour from abroad is highly unlikely.Footnote 38 Therefore, farmers largely prefer to use foreign workers that are already present and available on the Italian territory, as Section 4 shows.

4. Are seasonal migrant workers circular migrants?

As shown in Section 2, the Seasonal Workers Directive was expressly introduced to promote temporary and circular migration.Footnote 39 However, we have already seen that the reality of migrant seasonal farmworkers in Italy is far from that envisaged by the EU Directive. Of the hundreds of thousands of migrants working for Italian farms, only a few thousand of them hold a seasonal worker permit. What is the legal status of the rest of them?

Unfortunately, data on these workers is very scarce and information on their permits is not included in national surveys of the workforce. We have data on their citizenship though, from which we can deduce that around 40 per cent of them are EU migrants, even if this is a steadily decreasing number since Romania, Bulgaria, and Poland became part of the EU.Footnote 40 And probably these EU workers are the only true circular migrants, who come to Italy at the beginning of the season and go back to their country at the end, facilitated by the free movement rights attached to their legal status.Footnote 41

The only available source regarding the legal status of TCN farmworkers is the reports by the NGOs working on the ground to support migrants. For example, Figure 2 offers an overview of the residence permits of the farmworkers that in 2020 sought help from an NGO operating in the area of Saluzzo, a famous agri-food district in the North of Italy (Caritas Saluzzo Migrante).Footnote 42 Notably, these data are largely in line with those gathered by other NGOs operating in the South of Italy.Footnote 43

Figure 2. Percentage of residence permits held by migrant farmworkers assisted by Caritas in Saluzzo, 2020.

These data provided by NGO reports are partial and should not be used to draw general conclusions regarding the actual legal status of migrant farmworkers in Italy. They are gathered in areas especially affected by farmworkers’ poor conditions, where migrants live in informal settlements (‘ghettos’) and where their experience of severe exploitation is coupled with the suffering of ‘social exclusion, housing promiscuity, poor sanitation, lack of drinking water and heating, inhumane working conditions, incorrect or insufficient nutrition, and obstacles in accessing fundamental rights’.Footnote 44

And yet these data provide useful insights to debunk some of the myths attached to seasonal farmworkers. First, contrary to common beliefs that see them as undocumented, most of the (more vulnerable) workers hold a regular residence permit. Second, TCN farmworkers are not circular migrants but rather stable residents who are in the process of acquiring a permanent residence permit in Italy. Third, there is a discrepancy between migrants’ legal statuses and their job: notably, only a few of the migrants hold a permit connected to their worker status.

Maybe the main lesson to be drawn from these data is that they expose the incapacity of the Seasonal Workers Directive to protect and regulate the conditions of migrant seasonal workers. In its stated intention, the Directive wanted ‘to ensure decent working and living conditions and equal rights for those workers’,Footnote 45 granting workers equal treatment and equal access to social benefits. But none of the most vulnerable TCN farmworkers is minimally affected by the norms of the Directive. EU migration law fails to tackle the structural problems of seasonal work in agriculture which have to do with precarious and exploitative working conditions and the power imbalance between employer and employees.

The reason for this lies in how EU migration legislation is constructed. Its sectoral or fragmented approach means that each piece of legislation concerns only one category of migrants, identified on the basis of their residence permit (eg blue card holders, family members, long-term residents, etc) rather than their needs or work condition. This fragmented approach to the regulation of migrant status has been criticised for generating incoherence and confusion and for being ‘divisive’ both in terms of the objects and the subjects of migration and labour law.Footnote 46 Indeed, in the Italian crops, we have situations where migrants work for the same employers and have the same job contract but enjoy different rights because they hold different residence permits. For instance, under EU law, asylum seekers do not enjoy any right to equal access to social benefits, subsidiary protection holders have only partially equal rights, and single permit holders enjoy full equality with some exceptions.Footnote 47 Arguably, instead of increasing equal rights for migrants, this fragmentation risks reducing the impact of EU law and enhancing divisions between workers.

5. Conclusion: has the directive missed its target?

The Italian public discourse on seasonal farmworkers during the pandemic was largely based on misconceptions. In spring 2020, at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, Italian farmer associations launched an alarm: the ‘Made in Italy’ was in danger. The interruption to cross-border movements impeded 370,000 foreign workers to enter Italy, thus undermining the harvesting season and the production of apples, strawberries, kiwis, tomatoes, etc.Footnote 48 To compensate for their absence, the major farmer associations (CIA and Coldiretti) advocated for the introduction of special ‘vouchers’, alias hyper-precarious job contracts that would facilitate the speedy recruitment of farmworkers.

However, data on farmworkers presented in this article showed a different picture. Most of the migrant farmworkers employed in the Italian agricultural sector live in Italy on a stable basis and hold regular permits. Why then this outcry by the Italian farmer associations? Probably, this was partly due to the absence of EU migrant farmworkers, who left Italy at the beginning of the pandemic to avoid the risk of infection; and partly, this was a lobbying strategy of farmer associations that saw the pandemic as an opportunity to change the status quo: being hyper-precarious contracts, the vouchers would have simplified the recruitment procedures, lowered the price of labour, and deprived workers of some of their social protections. Eventually, trade unions prevailed: they managed to set aside the vouchers’ proposal and obtained instead a law for the mass regularisation of undocumented farmworkers.Footnote 49

This episode confirms that the agricultural sector in Europe is characterised by a race to obtain low-skilled and low-wage labour, to the point that often it becomes a grave source of exploitation and modern slavery. According to the segmented labour market theory, the import of low-skilled labour is due to the ‘imbalance between the structural demand for entry-level workers and the limited domestic supply of such workers’.Footnote 50 While in the past the demand for cheap labour was met by ‘women, teenagers and urban to rural migrants’, today for different social and economic reasons, these are no longer available.Footnote 51 One possible solution for the employers would be to attract local workers by raising wages, but this would impact on the entire occupational hierarchy, upsetting ‘socially defined relationships between status and remuneration’ (a waiter would not accept to be paid like a farmworker, etc).Footnote 52 Instead, the introduction of legal schemes for the temporary import of foreign labour offers a convenient solution to the employers’ problem of low-level labour shortage without disrupting social occupational hierarchies.

This paper showed that pieces of legislation such as the Seasonal Workers Directive ascribe to this model of migrant work regulation, by aiming to maintain segmentation in the labour market, helping farmers find highly disposable labour and keeping farmworkers’ wages low. However, the Directive was ill-designed and ultimately resulted in being only limitedly relevant, at least in the Italian context. This paper has also debunked some of the assumptions that underlie the current debate on seasonal farmworkers in Italy: data gathered before and during the pandemic show that most migrant farmworkers do not come from abroad for the harvesting season, are not circular migrants, and are not undocumented. This suggests that an exclusive focus on migrants’ legal status is not enough. To combat labour exploitation in the agricultural sector, we need to adopt policies that apply across statuses and that increase the bargaining power of farmworkers vis à vis farmers and food companies.Footnote 53 This would improve employment conditions in general, for third-country nationals, EU migrants, and national workers alike.

Acknowledgements

This article is one of the outputs of the research project ‘Covid-19 as an inequality challenge: Testing the EU response’. I would like to thank the other researchers working on the project, Camilla Borgna, Elena Corcione, Francesco Costamagna, Lorenzo Grossio, and Violetta Tucci; without them, this paper would not have come to light. I am grateful to the editors of the special issue and to the anonymous reviewers for their useful feedback. I would also like to thank all the participants in the workshop ‘Disentangling structures of migrant workers exploitation in the EU’s agriculture industry’ for their insightful comments on an early draft. Errors are all mine.

Funding statement

The research conducted for this paper was supported by a grant from Collegio Carlo Alberto.

Competing interests

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.