In the 1590s, civic officials of the Medici grand duchy began posting stone plaques in Florence's streets and squares inscribed with laws prohibiting specific activities and the sounds and smells they produced. The engraved plaques were commissioned by Florence's long-standing policing magistracy, the Otto di Guardia, or Eight for Safety, and affixed to the outer walls of institutions, squares, churches, street corners and private homes. This practice continued into the eighteenth century with the last known plaque posted in 1771. A typical inscription is one installed in 1696 on the exterior wall of the Ospedale dei Mendicanti, the Mendicant poor house, a large charitable home in Florence's impoverished south-western neighbourhood. The plaque prohibited ‘any person to play any sort of game, to play instruments and to make racket in any form, during the day or night within 60 metres [100 braccia] of the Mendicanti under penalty of arbitration and capture’.Footnote 1 Another plaque from 1620 near the venerable Santa Maria degli Angeli monastery in the city's north end prohibited anyone ‘to piss or to make filth’ in the surrounding area.Footnote 2

A total of 86 engraved plaques have survived in varying conditions and many can still be seen throughout Florence today.Footnote 3 Of this total, approximately 83 date to the Medici grand ducal period (1569–1737). Other plaques were almost certainly posted during the grand ducal period, particularly in the city centre where nineteenth-century reconstruction projects re-modelled the urban core, demolishing many buildings and their inscriptions.Footnote 4 The surviving Otto di Guardia plaques are all rooted in sensory concerns: the smells of waste and urine, the sight of ‘dishonourable’ individuals and the sounds of urban din and sociability (see Tables 1 and 2).Footnote 5 Sonic laws are particularly common with explicit prohibitions against ‘noise’, ‘tumult’, ‘racket’, ‘singing’ and ‘instrument playing’; implicit sonic prohibitions forbade noisy sex workers, resounding games and ‘filth’ made by shouts, songs and lewd words.Footnote 6 The plaques reference smells by variously regulating public urination, waste disposal and malodorous trades like tanning. Prohibitions against general ‘filth’ and ‘foulness’ are particularly common, both terms are used interchangeably to reference sounds and smells.Footnote 7 Together, these stone artifacts point to the entwined immaterial, material, sensory and spatial histories of late Renaissance Florence.

Table 1. Frequency of sonic prohibitions in grand ducal stone plaques

Table 2. Frequency of olfactory prohibitions in grand ducal stone plaques

Late Renaissance societies invested the senses with profound importance. Sounds, smells, tastes, textures and sights were understood as formative agents that shaped individual bodies and the body social.Footnote 8 This sensory focus can be traced to a number of intersecting factors. First, rapid urban growth in many regions. As European cities expanded over the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, urban denizens often lived in crowded conditions and mixed commercial and residential spaces with varying levels of infrastructure. Smells and sounds, and efforts to contain them, highlighted the complex spatial and demographic dynamics that defined many early modern cities.Footnote 9 Religious upheavals of the Reformation also brought a unique focus to the senses. Philip Hahn has shown how Lutheran preachers in Germany enacted an ‘acoustic semantic change’ that sought to reform bell-ringing, stripping away the ‘pomp’ they associated with ‘vain and ostentatious’ bells favoured by ‘papists’.Footnote 10 Another critical factor was the increasingly global nature of European interactions, particularly in colonial and imperial contexts. The Columbian exchange ushered in an abundance of new flavours that altered the European palate.Footnote 11 Moreover, many European writers used the senses to support colonial and imperial endeavours, circulating evocative descriptions of the perceived sounds, smells, sights and bodily traits of the ‘others’ they engaged with.Footnote 12 Cultural encounters mediated the creation of sensory hierarchies that bolstered the constructed cultural and racial hierarchies inherent to colonialism and imperialism.Footnote 13 Finally, early modern medical theory rested on the fundamental assertion that the senses penetrated the human body and altered the humours and spirits; determining individual and public health for better or worse.Footnote 14

Despite the profound importance of the senses in the late Renaissance, their ephemeral and often immaterial nature can make these histories challenging to link to precise spaces and groups. Analysing Florence's sensory prohibition plaques presents a valuable opportunity to investigate links between sense and urban space. Unlike the smells and sounds that the plaques reference, which drifted and dissipated, these artifacts are fixed in space. Traces of Florence's ephemeral history are embedded into the city walls. The stone inscriptions reveal how particular streets and squares were experienced and reference the sensory tensions that animated public space. The plaques also reflect how grand ducal officials attempted to regulate the urban sensescape, limiting certain sounds and smells and disciplining those who created them.

This article analyses the Otto di Guardia stone plaques by situating them within the social and political context of the Medici grand duchy. It examines the plaques’ content by focusing on two labour groups explicitly referenced in the inscriptions: women sex workers and tanners. Civic efforts to regulate the sounds and smells that sex workers and tanners produced shows how sensory legislation was directly linked to dynamics of gender, class, labour and space. The final section considers how GIS mapping of the inscriptions reveals two distinct patterns.Footnote 15 First, sensory prohibitions became more precise over the course of three centuries, shifting from broad proclamations about general decorum to highly detailed laws about particular types of sensory offences. Second, laws became progressively more focused on the relationship between sense and space by prohibiting sounds, smells and activities within carefully measured prohibition zones that encompassed larger geographical areas over time.

Examined collectively, the plaques reveal how sensory regulation emerged as an increasingly publicized element of urban governance in grand ducal Florence. Earlier fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Florentine governments had issued sensory legislation and, as Niall Atkinson has shown, constructed ‘a coordinated sonic regime’ centred around bellringing that was ‘meticulously regulated by statutes, conventions, ancient privileges and legal sanctions’.Footnote 16 Moreover, the Otto di Guardia had served as Florence's disciplinary office since the fourteenth century and monitored urban activity. However, the creation and proliferation of the plaques in the sixteenth, seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries reflect a heightened focus on quotidian sensory regulation during the grand ducal period. This focus was propelled by the centralizing bureaucracy of Medici Florence, highly localized tensions over sensory production rooted in dynamic social geographies and the broad early modern cultural investment in the importance of the senses. These factors coalesced and sensory legislation emerged as an important means of social discipline in the late Renaissance city. Most often, this was an ad hoc and reactive process. Officials responded to the city's continually unfolding sensescape with regulatory efforts that sought to discipline space and sensory production. However, the presence of these laws also points towards a daily reality in which Florentines produced sounds and smells and used urban space in ways that extended far beyond the ideals outlined in the inscriptions. Echoes of vibrant quotidian sensescapes are referenced in the Otto di Guardia's regulatory efforts. Ultimately, the plaques do not reflect a singular sensescape nor a singular use of space. Instead, they reveal manifold and shifting registers of urban sensory experience.

Stone plaques and the Medici grand duchy

In January 1551, the Florentine nuns of San Pier Martire, a Dominican convent on the southern outskirts of the city, complained to the Otto di Guardia about the incessant noise surrounding their convent. In response, the Otto legislated that ‘in the future no one can go within 120 metres of this convent to sing, throw stones, gather or make other noises under penalty of 20 scudi’.Footnote 17 But the law did little to deter groups from gathering near the convent to socialize. A year later, the nuns claimed they were still harassed by these sounds, and in 1552, the Otto enacted sonic legislation again, prohibiting ‘anyone…[from] playing games anywhere near that convent…nor to make or say any kind of filth or dishonest words…under the penalty of 20 scudi’.Footnote 18

In 1557, the convent was torn down to allow for refortifications of the city walls and the San Pier Martire nuns moved to a new complex near Palazzo Pitti, the new residence of the Medici duke and duchess.Footnote 19 If the nuns had hoped their new location would offer more regulated soundscapes, they were quickly disappointed. Here again, they were plagued by sounds that drifted over their cloister walls. This time, the sounds came from women sex workers and their clients who solicited business in the surrounding area. Groups of men and women hollered, fought, sang songs, played instruments and had loud sex. Several decades later, in 1606, the Onestà, or Office of Decency, Florence's magistracy governing the sex trade, proclaimed in a somewhat exasperated tone their hope that ‘in the future these nuns will not have any more disturbances from prostitutes who live near their convent and particularly closest to where they have their dormitory’.Footnote 20 Civic officials took one more step and carved the legislation into a stone plaque, posting it on the outer wall of the convent for all those who passed by to see. The undated plaque declared that ‘the honourable Otto prohibit [anyone] to play games and make filth etc. near the church and convent under the usual penalties’ (see Figure 1).Footnote 21 The plaque remains as a succinct reminder of the five-decade struggle to discipline the convent soundscape and its surrounding area, embedding this history into the outer wall.

Figure 1. Plaque near San Pier Martire convent. Photograph by author.

Florentines had long used public inscriptions and symbols as markers of space and influence. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Medici family had embarked on an ambitious project of patronage that sought to solidify their growing influence in the city.Footnote 22 The construction of ornate monuments and strategic placement of the Medici coat-of-arms on the exterior of many buildings injected the Renaissance cityscape with notions of Medici dominance.Footnote 23 Other patrician families and guilds likewise inscribed their insignia into the city's structures to ensure their influence would not be forgotten. These symbols existed alongside dozens of corner tabernacles that imbued streets with sacred meanings.Footnote 24 Late Renaissance streetscapes were multivalent spaces that eschewed simplistic categorizations of ‘public’ and ‘private’, and symbols, signs and shrines reflected this vibrant complexity.Footnote 25 Built space was a battle ground for urban dominance, and the symbols that decorated building exteriors reflected the complex political manoeuvrings of the Renaissance centuries. The Otto di Guardia plaques are part of a broader material history in which ruling families, civic governors, influential institutions, religious authorities and administrative bodies used self-reflexive symbols in an attempt to claim urban spaces in their name.Footnote 26

Why did the Otto di Guardia, which had served as Florence's disciplinary office since 1378, begin publicizing sensory legislation in the late sixteenth century? Part of the answer lies in the changing nature of governance in the early years of the grand duchy. By the time the Otto began to post plaques in earnest, the Medici had established a dynastic line of grand dukes and duchesses who ruled Tuscany. The appearance of the plaques roughly corresponds with the protracted ‘emergence of a bureaucracy’ and ‘negotiated absolutism’ that took place in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote 27 After the collapse of the Republic, Medici rulers, beginning with Cosimo I de’ Medici (r. 1537–87), enacted sweeping reforms that served to centralize governance and encourage patrician acceptance of princely rule. In particular, the Otto and many other Tuscan magistracies were restructured, bringing these administrative bodies and their resources firmly within the orbit of Medici control. From the mid-sixteenth century on, the offices of the Otto were almost always stacked with Medici loyalists. While the Otto grew beyond its original number with the creation of new positions and a significant expansion of Medici bureaucratic governance, its financial and legislative independence diminished.Footnote 28 These administrative centralizing shifts coincided with a broader legislative push whereby laws regulating quotidian social behaviours were rapidly enacted and disseminated throughout the grand ducal period. Elena Fasano Guarini has shown that the first Medici grand duke, Cosimo I, ‘can in effect be considered one of the great “princely legislators” in a period of intense legislation’.Footnote 29 Starting in the 1530s, the Tuscan duchy and grand duchy issued the ‘repetitive production of rules and regulations’ on a wide variety of everyday issues: public decorum, sumptuary laws, public gatherings, gambling and games, carrying arms, injurious words and public indecency.Footnote 30 By the time Ferdinando I de’ Medici ascended to power in 1587, a focus on sensory, social and spatial discipline had emerged as a defining feature of grand ducal governance and the Otto had developed as a central branch of civic discipline that remained tightly linked to Medici rule. The stone plaques are material manifestations of these interconnected dynamics.

The stone inscriptions are a reflection of both Florence's changing political framework and a larger history in which early modern rulers with centralizing ambitions were keenly focused on regulating social and sensory behaviours.Footnote 31 In Florence, the Otto identified meaningful public sites around which to structure these legislative efforts and marked them with publicly displayed laws. For example, in 1720 an inscription was affixed to the outer wall of Florence's government palace next to the ornate Fountain of Neptune in Signoria Square. The inscription reissued a 1646 law that prohibited any ‘foulness’ within 12 metres and forbade anyone to wash ‘inkpots, clothes or any other materials’ in the fountain's waters.Footnote 32 Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici had commissioned the fountain in 1559 to symbolize Tuscany's command of the Mediterranean, and it stood in the city's central square. The sights, smells and sounds of Florentines washing dirty laundry and inkpots in this politically charged space no doubt dampened the intended grandeur of the fountain, as they clouded Neptune's basin with filth. Odorous inky waters and sullied laundry reminded passersby of unglamorous realities that did not align with either the fountain's subject or its intended reference to grand ducal naval prowess.Footnote 33 The stone inscription placed on the palace wall thus sought to assert control over the space and its messaging. Inscribing these rules into the palace walls confirmed the state's investment in monitoring urban space and sensory activities. In this way, the actions of average Florentines and the smells, sights and sounds they produced were linked to grand ducal political ambition.

However, civic officials faced an uphill battle as they sought to regulate space and sense; posting laws often failed to stop the sensory behaviours that grand ducal officials perceived as problematic. It is likely that Florentines continued to use the Fountain of Neptune to launder soiled items, drawn to the conveniently located waters. And despite all efforts, people continued to sing, shout and solicit sex near the San Pier Martire convent, as evidenced by the nuns’ repetitive complaints. The prevalence of the stone plaques throughout Florence reflect two forces in tension. First, the regulatory efforts of the Otto and the Medici grand duchy. Second, the diverse sounds and smells Florentines created as they easily ignored, or were unaware of, the city's expanding corpus of sensory decrees. Sensory and spatial surveillance emerged as an important element of centralizing urban governance in grand ducal Florence, but socio-sensory discipline was always ‘in the making but never made’.Footnote 34

Sex workers, tanners and sensory legislation

The Otto di Guardia's stone inscriptions reveal how conflicts over public space, who occupied it and how it was used were often negotiated via the senses. The placement of individual plaques responded to highly localized tensions about sound and smell and were directly linked to experiences of gender, class and labour. This was particularly the case for two distinct groups: women sex workers and tanners.

A total of 10 plaques explicitly legislated sex work. For example, an inscription in the city's north-eastern quarter prohibited ‘prostitutes or dishonest women of any kind to stay and live near that convent [of San Silvestro] within sixty metres in every direction under penalty of 200 lire as per the decree of 9 June 1668’.Footnote 35 Other plaques implicitly referenced sex work by prohibiting the ‘foulness’ and ‘tumult’ associated with the sex trade. These were sonic prohibitions. Complaints about noisy sex work fill the Florentine archives and describe the shouting, disruptive fighting, socializing and clattering sound of coaches moving in and out of sex work zones. In May 1560, three male weaving apprentices were fined ‘for having gone in the night…to the house of Bita the prostitute…and made noise’.Footnote 36 Criminal records from 1577 accused the sex worker Monica di Antonio Carbacci of continually ‘passing through the street in a coach, [where] she made racket, injurious noise, and impropriety’.Footnote 37 In 1629, the Otto fined ‘four youths’ for ‘playing the gittern and singing at night at the house of a prostitute near the San Giuliano convent’.Footnote 38 These sounds were considered noise, baccano, because of their social and gendered implications. Moralizing social boundaries patterned sonic boundaries, leading these sounds to be labelled offensive and damaging.

Complaints about noisy sex work were particularly heightened in and around the city's many convents. Not only were convents sacred spaces, but they were also highly gendered sites where idealized femininities were performed and preserved. The sounds of ‘dishonest’ sex workers threatened to disrupt gender norms and the cultures of honour that nunneries worked to uphold.Footnote 39 A 1454 law by the Otto therefore banned women sex workers from living or gathering within 180 metres of convents.Footnote 40 Once Cosimo I de’ Medici assumed power in 1537, moralizing limitations on sex work continued. A series of 1547 laws listed only 18 streets where sex workers could legally live and work, with four more street sections added in 1558.Footnote 41 Essentially all of these streets were located in the peripheries of the city where civic officials hoped to quarantine the sights and sounds of sex work far from the city centre.Footnote 42 Laws from 1547 also decreed that ‘prostitutes and dishonest women, single or married, citizens or foreigners cannot live within 60 metres of any convent of cloistered nuns within the city of Florence, under penalty of 200 lire’.Footnote 43 In the following decades, urban authorities continually reissued and expanded these laws. Decrees from the 1564 Florentine synod sought to double exclusion zones around convents, proclaiming that ‘prostitutes who are publicly registered with the Onestà…cannot live within 120 metres of convents’.Footnote 44 In 1620, the last year of Cosimo II de’ Medici's rule, the Onestà limited sex workers' freedoms by forbidding them from travelling at night without permission, stating that those apprehended would be incarcerated.Footnote 45 In 1665, Ferdinando II de’ Medici decreed that ‘prostitutes who are further than 60 metres from a convent can be removed, if with their insolent life convents suffer the prospect of scandal’.Footnote 46 Stone plaques enumerating sex work restrictions were material manifestations of the progressive legal marginalization of sex work in grand ducal Florence. The plaques were highly localized applications of general laws that aimed to contain the shouts, screams, laughter and clatter associated with sex work.

All of these efforts had little success. Throughout Florence, sex workers and nuns remained tied together in overlapping soundscapes. In part, this was because of the expansive growth of Florentine convents, in both number and size, in the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, a shift that convent scholarship has tracked in detail.Footnote 47 During this same period, Catholic reforms advocated for increasingly strict cloisters that permanently separated enclosed women from the larger city.Footnote 48 As convents and their populations grew, it became difficult to separate these crowded communities of girls and women from the broader urban soundscape. Moreover, many of the city's newer convents, in search of available space, were located in the same peripheral neighbourhoods where sex workers were corralled according to new civic laws.Footnote 49 These intersecting social geographies were a regular source of sensory tension and are reflected in the stone plaques that cluster in these outer neighbourhoods.

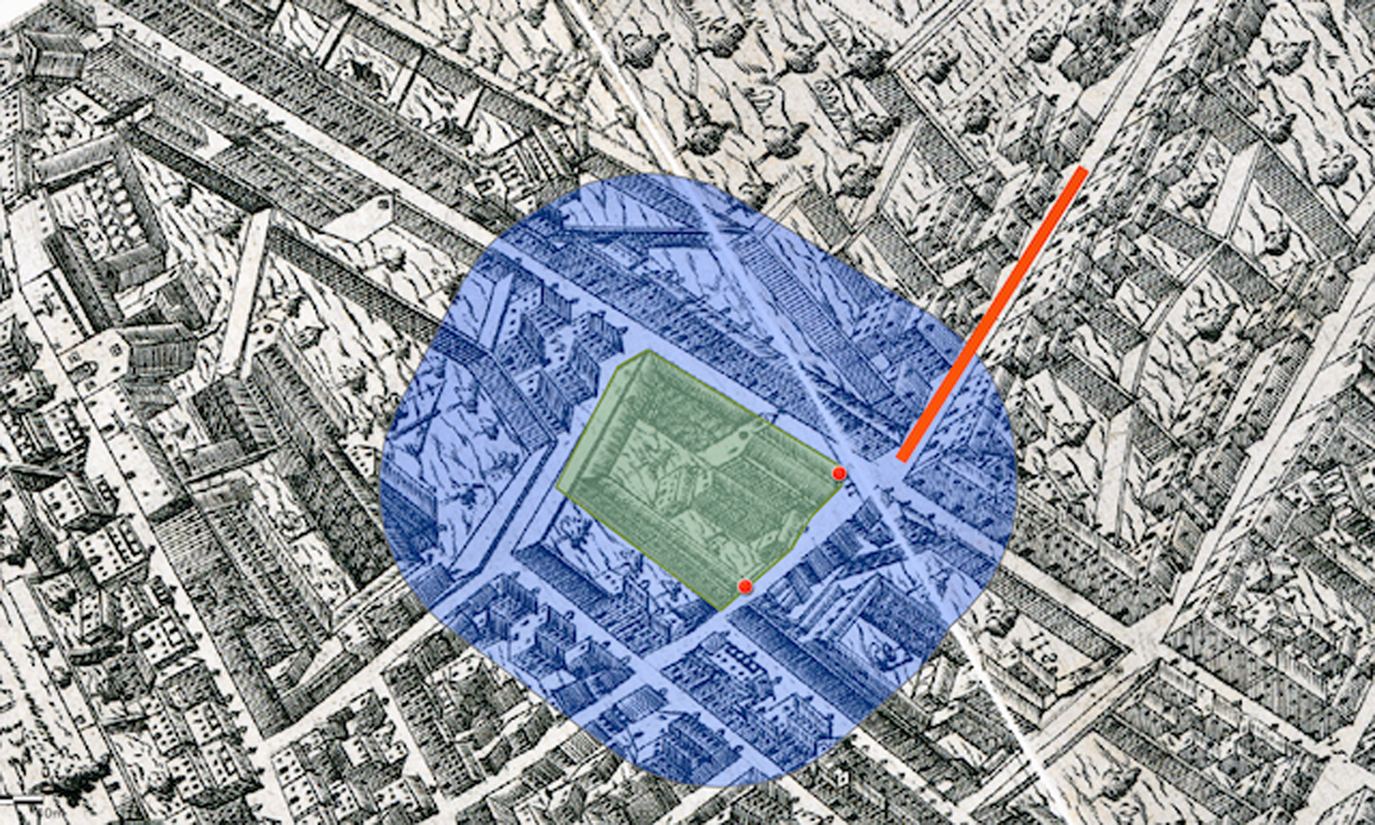

Two plaques placed near the San Barnaba convent in Florence's north end illustrate these sonic and spatial dynamics. The first plaque banned ‘prostitutes or similar women around the church and monastery of S. Bernaba within sixty metres according to the 1561 law’.Footnote 50 The second plaque prohibited ‘every sort of foulness, games or tumult around the church and walls of the nuns of S. Barnaba’.Footnote 51 Much of this perceived ‘tumult’ came from sex work. The Carmelite convent had opened in 1508 at the corner of via Mozza, one of the permissible sex work areas outlined in 1547 laws (see Figure 2).Footnote 52 As sex workers moved into the neighbourhood, complaints about noise near the convent rose. In 1572, the Onestà reported that the sex worker Sandra had been ‘found opposite from the convent of Santa Barnaba with two male youths, howling and saying dishonest words without respect to the space’.Footnote 53 A few years later, in 1575, ‘four women [sex workers] living in via Mozza’ were fined for ‘having made noise’ near the convent.Footnote 54

Figure 2. Via Mozza (red line), San Barnaba convent (green), plaques (red dots) and 60-metre sex worker exclusion zone (blue) (in colour online). Map created by author using ArcOnline and geo-referenced Stefano Buonsignori map courtesy of the Digitally Encoded Census Information Mapping Archive (DECIMA).

The Otto di Guardia's stone inscriptions aimed to delineate a sonic and spatial boundary separating ‘dishonourable’ sex workers from ‘honourable’ nuns. The plaques were meant to act as a bulwark protecting against sonic and social overspill. However, they also attest to the complex socio-sensory dynamics whereby sex workers and nuns often shared soundscapes. These material artifacts attune us to the unique hearing culture of the late Renaissance city. Florentines listened carefully to neighbourhood sounds and understood them to carry meaningful messages. The ‘quest for quiet’ rested on assertions of sound as a social cue and related assertions about who needed to be silenced.Footnote 55 Urban officials used sonic legislation to reinforce hierarchies of gender, claiming that sex workers and their sounds polluted urban space and assaulted cloistered girls and women. However, these same inscriptions also reveal how sex workers asserted their agency and resisted spatial, social and sonic marginalization. Consciously or not, when sex workers made these sounds they defied claims that they did not have a right to occupy public spaces.

Other plaques were primarily concerned with smell. An inscription from 1720 placed in via delle Conce, Tanners Street, in the city's working-class eastern district proclaimed that ‘leather and hide tanners of any sort cannot keep myrtle leaves, lime or other materials in the streets for longer than four days under penalty of 25 lire’.Footnote 56 Tanners stripped hair from hide in outdoor water-workshops and then soaked animal skins in vats of noxious bio-materials. Myrtle leaves and lime mortar were regularly used ingredients. Urine and guano were commonly used astringents in the process. This pungent work took months or even years and leathers then needed to be hung to drip-dry.Footnote 57 Tuscans complained about new tanning workshops that opened near them and bemoaned the smells they produced.Footnote 58 In 1887, Florentine historian Francesco Bigazzi discussed the 1720 stone inscription in via delle Conce, writing:

it is really a shame that in a city like Florence, in our time, one still has to allow a similar trade [tanning]. It is said that the sickly odour continually exhaling from that place is safe; but for me it could be as hygienic as you want, but I am unable to deny that those streets are the shame of the city; degrading it truly to the point of a being a sewer.Footnote 59

Early modern efforts to regulate tanning smells were rooted in concerns about public health. While Bigazzi referenced prevailing nineteenth-century medical theory to begrudgingly claim these smells were safe, albeit unpleasant, sixteenth-, seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century Italians were adamant that such smells were dangerous pollutants and inimical to good health. In Bernardino Ramazzini's 1745 occupational health text, The Diseases of the Trades, the Modenese physician discussed the dangers of tanneries, writing ‘every time I set foot in such places I confess that I felt quite upset in my stomach and I could not suffer that bad smell for long without a headache’.Footnote 60 Late Renaissance medical theory went further and claimed that putrid odours prompted the miasmic vapours thought to spread plague and disease.Footnote 61 In 1622, Florentine officials declared: ‘in well-ordered places there are statutes and orders which prohibit the keeping of rubbish in the streets, squares and other places; since this rubbish tends to give off smells and stenches which are so damaging to health’.Footnote 62 Regulating odiferous trades like tanning was a commonly implemented public health practice throughout Italy, particularly during plague outbreaks. In August 1576, Milanese civic officials, confronting a severe plague, decreed that ‘for the next two months no one is allowed to tan any leathers in Milan’.Footnote 63 In 1630, when northern Italy was gripped by another deadly plague, Florence ordered that ‘in public streets and places no one will be allowed filth nor to make waste nor to tan leathers’.Footnote 64 In 1630, Bologna published similar laws to ‘keep the streets and houses of the city clean and purged’ and ordered that ‘every night all tanners…must take away any waste they will extract from leathers they will tan’.Footnote 65 The 1720 plaque in via delle Conce, erected in the wake of a centuries-long fight against plague, referenced the intersecting sensescapes and healthscapes that shaped urban experience in this eastern quarter of the city. The plaque, alongside those prohibiting public urination, waste and ‘foulness’, testify to the intimate links between smell, space and well-being in the pre-modern city.

Plaques regulating sex work and tanning show how social and environmental pollution were linked concepts with direct spatial implications. Though not as denigrated as sex work, tanning was nonetheless undesirable and putrid odours often made it an unwelcome trade. Both of these ‘polluting’ sensory groups were pushed to the outskirts of the city and urban officials were tasked with regulating these peripheral sensescapes. Indeed, the physician Ramazzini advised that tanneries should be ‘located near the city walls along with other sordid trades’.Footnote 66 Much like how plaques regulating sex work clustered in the urban outskirts where sex workers were forced to work, the 1720 tanning plaque was located near the city walls in the eastern Santa Croce quarter, an area long associated with tanning, dying, butchery and the odorous materials these trades relied on.

According to Florence's 1561 census five tanners lived in Santa Croce, alongside three tanning workshops in via delle Conce.Footnote 67 The area was also densely populated with dyers. Of the city's 99 listed dyers, 60 lived in the Santa Croce area and the majority clustered on Volta dei Tintori, Dyer's Way, near the Arno river which provided access to the water tanners and dyers needed to mix dyes, soak skins and dispose of pungent liquids.Footnote 68 In the 1632 census, for which occupational records are incomplete, 9 tanners were listed in via delle Conce and a total of 19 tanners lived in the Santa Croce district, suggesting that more tanneries operated in the area as the grand ducal period progressed.Footnote 69 Similar sensory and spatial dynamics existed in other early modern cities. William Tullet has shown how in eighteenth-century London and Manchester concerns about malodorous tanneries became more acute as part of the ‘sensory crisis of industrialization’, building on centuries of ‘distaste for offensive trades’.Footnote 70 Tullet has also noted how increasingly bureaucratic eighteenth-century governments publicized and recorded these sensory concerns in greater detail, at the same time that emerging medical models were critiquing classical theories of miasma.Footnote 71 Similarly, the 1720 inscription regulating tanneries in Florence connects to the long olfactory history of the city's eastern working-class district, alluding to smells that defined the area before, during and after the carved stone was first created. Together, plaques referencing sex work and tanning reveal how Florence's sensescapes and social geographies were fundamentally shaped by dynamics of class, gender and labour; dynamics that became increasingly publicized in the plaques over the course of the grand ducal period.

Tracking patterns in the stone laws

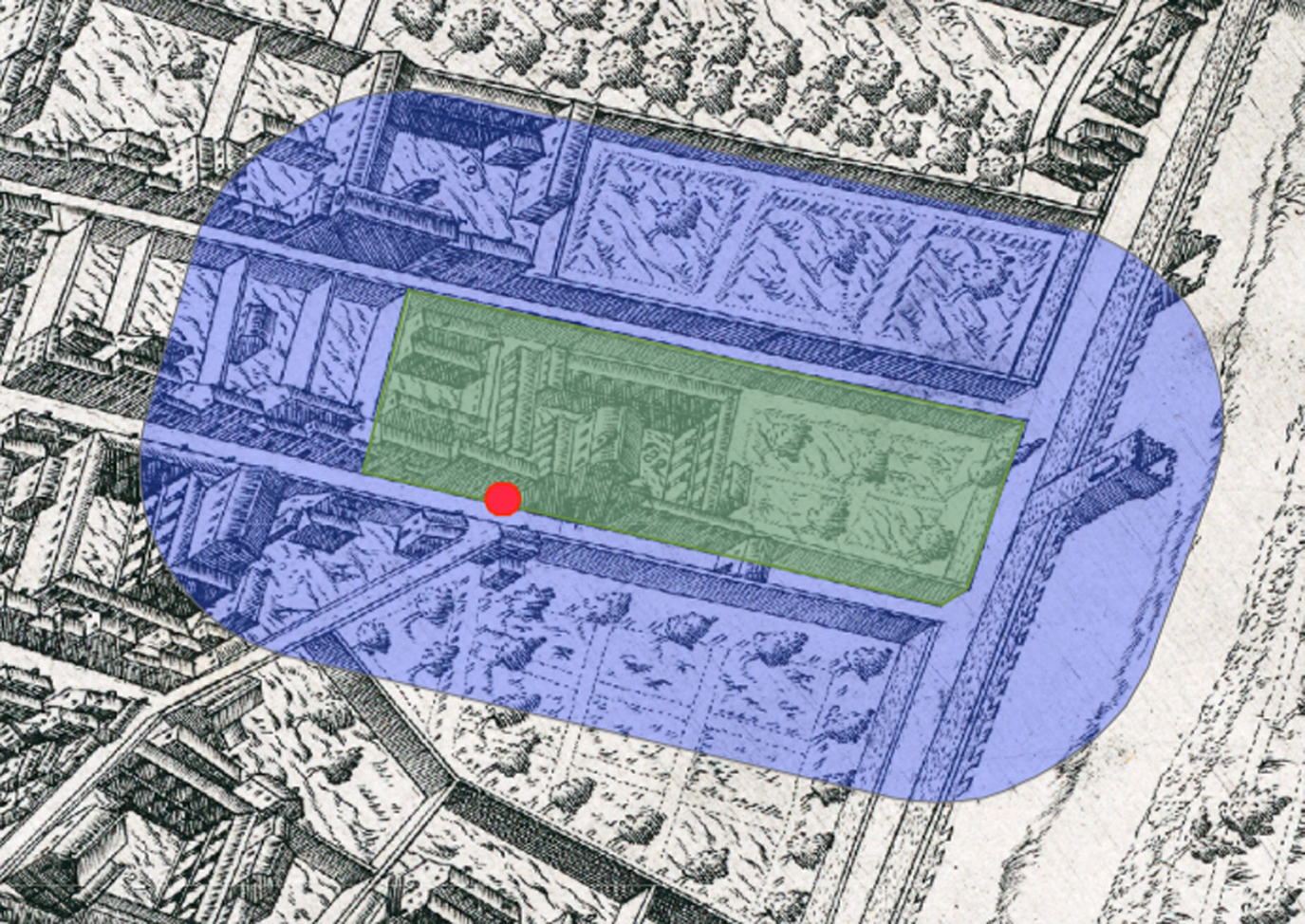

Mapping all 83 plaques offers a broad view of the socio-sensory regulations that proliferated across the late Renaissance city and shows how stone inscriptions were spread throughout Florence over the course of three centuries, appearing in each of the city's four quarters and dotting the cityscape in a fairly even distribution (see Figure 3). By the mid-1700s, the Otto had posted sensory legislation in virtually every neighbourhood. A particularly valuable element of the plaques is their regular inclusion of precise sensory measurements. For example, an inscription from 1616 near the Le Murate convent on the eastern edge of the city prohibited ‘children playing ball games or any other kind of game, and at night instruments and singing songs [are prohibited] around the convent and within sixty metres’ (see Figure 4).Footnote 72 These spatial measurements reveal how Florentine officials conceptualized the reach of sensory productions and outlined measured prohibition zones throughout the city.

Figure 3. Surviving Otto di Guardia plaques from Medici grand ducal period (in colour online). Map created by author using ArcOnline.

Figure 4. Plaque (red) and 60-metre quiet zone (blue) around Le Murate convent (green) (in colour online). Map created by author using ArcOnline & DECIMA.

Creating a precise chronology of the stone plaques proved difficult because only 39 plaques bear dates. The 44 remaining plaques have been assigned to date ranges corresponding to three general periods of grand ducal rule.Footnote 73 The assignment of each undated plaque within these periods was based on its content, references to specific legislation and similarity in content and quality to dated stones from that period. Determining measured legislative zones for each plaque raised similar issues. A total of 50 plaques explicitly outline sensory measurements like the 60-metre quiet zone around the Le Murate convent while 33 remain vague. These were assigned exclusion zones corresponding with those most commonly stipulated according to the type of regulation. Laws concerning sex work most often outlined a 60-metre exclusion zone; ball playing, gaming and music laws usually stipulated a minimum of 60 metres and ‘racket’ and noise prohibitions usually outlined a minimum of 30 metres. Despite these methodological challenges, mapping the plaques uncovers interesting patterns and new information about grand ducal Florence. In particular, mapping reveals how sensory legislation became progressively more specific, more spatially focused and encompassed larger geographical areas over time.

The oldest surviving dated plaques are from 1596 and 1598. Both plaques, along with most of the other oldest surviving stone laws, are located in the urban centre near the Ponte Vecchio and the government offices (Uffizi), at the city's political and cultural heart. Like many surviving plaques in this central area, the oldest dated and undated plaques simply stated that ‘the Gentlemen of the Otto have prohibited filth’ (see Figure 5).Footnote 74 Prohibitions against ‘filth’ could include a wide variety of activities that often combined social and environmental notions of pollution: the noises of the sex trade, boisterous homo-social gatherings, public urination, waste disposal and game-playing and gambling. In their earliest iterations, surviving stone laws were unspecific, generalized and geographically confined to the centre of the city.

Figure 5. Earliest plaques in city centre with 12-metre ‘filth’ prohibition zones (in colour online). Map created by author using ArcOnline & DECIMA.

Beginning in the seventeenth century, the content of the plaques began to change. Sensory prohibitions became more specific and the varieties of sensory impropriety more clearly articulated. This is particularly observable in sonic laws. Inscriptions from the 1610s, 1620s and onwards began to parse sonic productions with new specificity. Rather than repeating catch-all laws against ‘filth’, these plaques outlined detailed prohibitions against tumult, noise, singing, instrument playing and clamour. For example, a plaque from 1664 is markedly more specific than the 1596 plaque prohibiting generalized ‘filth’. The 1664 inscription, placed near the Santa Maria di Candeli convent in the central eastern area of the city, banned ‘games, songs, and instruments and other sort of racket or noise around this convent and within 60 metres in all directions’.Footnote 75 There is a direct spatial correlation to these more specific inscriptions. Many of the later and more precise laws were located in the city's outer neighbourhoods. While nineteenth-century redesign of the city centre and the subsequent destruction of many plaques may partially account for this pattern, this spatial shift also reflects how social and sensory discipline was increasingly focused on the areas of the city where ‘problematic’ socio-sensory groups like sex workers and tanners clustered. Social and spatial peripherality were linked and the city's resulting sensory geographies were publicized via stone inscriptions.

Sensory prohibition zones also expanded over time. The earliest inscriptions banning ‘filth’ that clustered in the urban centre did not reference any physical boundaries, and the earliest dated measurement is from 1603 in a plaque outlining a 12-metre sanitation zone where any ‘foulness’ was prohibited.Footnote 76 As the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries progressed, a general trend emerged whereby measured sensory zones became more common and encompassed progressively larger areas. Of the plaques containing explicit measurements, none are dated to the sixteenth century and 22 can be definitively dated after 1621.Footnote 77 From this period on, sonic prohibition zones grew in size at a steady pace. For example, a 1634 plaque outlined a 120-metre area where playing instruments, singing and games were prohibited.Footnote 78 A 1635 sex work plaque tripled the traditional 60-metre sex work boundary, stipulating a 180-metre exclusion zone around the Ognissanti church in the city's western quarter, an area densely populated with sex workers.Footnote 79 Expanding sensory measurements culminated in 1700 with an inscription that prohibited ‘games and racket’ within 480 metres in all directions around the San Pietro in Gattolino church located in Florence's southernmost corner near the city gates.Footnote 80 Mapping this nearly half-kilometre zone reveals that it encompassed much of the southern quadrant of the city and even extended beyond the city walls, once again confirming a growing sensory focus on Florence's peripheral spaces (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Plaque from 1700 near San Pietro in Gattolino church with 450-metre quiet zone extending beyond city walls and boundaries of the Buonsignori map (in colour online). Map created by author using ArcOnline & DECIMA.

The emergence of expansive sonic exclusion zones raises questions about the extent to which sensory legislation was enforced. It would have been all but impossible to monitor the half-kilometre soundscape around San Pietro in Gattolino in any absolute sense. Moreover, there is no archival evidence that the Otto consistently monitored areas around the stone plaques. Nor is there evidence that officers of the Otto regularly collected the fines outlined in many of the plaques, fees most Florentines would have been unable to afford.Footnote 81 While late Renaissance Florence was a highly policed space with guards stationed at gates, institutional entrances and civic buildings, the city had a limited number of roaming neighbourhood police. The 1632 census listed 44 policemen, birri, but most were assigned exclusively to specific gates and main market squares.Footnote 82 In large part, the Otto relied on neighbourhood informants to monitor local spaces, a process that likely explains how many plaques were erected in the first place.Footnote 83 In the same way that the plaques preserve a record of the sounds and smells they aimed to limit, their very presence gestures towards the limited influence of the Otto at the highly localized level. In daily life, many Florentines likely ignored or were unaware of these sensory laws. Despite these realities, the increased specificity of sensory prohibitions and expansive exclusion zones reflects the grand duchy's heightened investment in the idea of sensory regulation as a means to discipline urban space and sociability. The plaques reflect the sensory aspirations of the Otto and some neighbourhood locals, but not the realities.

Conclusions

Florentine officials relied on sonic and olfactory cues to mediate space and sociability. Mapping the Otto di Guardia's surviving stone plaques from the grand ducal period visualizes the late Renaissance city in a new way. These material artifacts testify to the profound importance Florentines invested in the immaterial world of the senses. The sounds of sex work and the smells of tanning communicated important messages about gender, class, health and urban space. Over the course of the Medici grand ducal period, sensory legislation became more pervasive, more specific and more public. Grand ducal officials increasingly used sensory legislation in an effort to discipline space and sociability, with particular emphasis on the urban outskirts where working-class and marginalized groups gathered – often at the behest of civic authorities. The stone plaques were material efforts to make the immaterial world of the senses trackable, measurable and definable while publicizing social hierarchies. Publicized sensory legislation was a product of the centralizing and bureaucratic grand ducal government, shifting urban dynamics that saw groups like sex workers pushed to urban peripheries and labelled ‘offensive’ and a broad early modern investment in the power and impact of the senses. However, sensory legislation was never enforced in any absolute sense and Florentines continued to produce dynamic sensescapes.

Thinking sensorially unsettles the urbanist priority on optics, drawing our attention towards the layered acoustics and aromas that animated spaces. Analysing ‘sensuous geographies’ reveals how the late Renaissance cityscape came to life.Footnote 84 Shouts, talking and ‘howling’ reverberated through the city's squares and drifted over walls. Likewise, narrow streets prevented the quick dispersal of pungent aromas. By embedding sonic and olfactory regulations into the city walls, urban officials acknowledged built space as both the culprit and the potential solution to a noisy and smelly city. Traces of idealized and dissonant sensescapes are preserved in Florence's public spaces, binding textual and ephemeral histories together. Ultimately, the plaques reflect an inherent paradox as bureaucratic attempts to regulate sounds and smells are deeply at odds with the shifting and subjective nature of sensory experience.