The Creole Debate is, essentially, the question of whether or not creole languages constitute a typological class based on structural properties. One area that has figured prominently in this debate is their tense-mood-aspect systems, and, in particular, preverbal markers, which, according to the traditional view, have specific syntactic and functional roles that distinguish creole from noncreole varieties (Bickerton, Reference Bickerton1975, Reference Bickerton1981, Reference Bickerton1984; see Holm, Reference Holm1988:148–51 for discussion). This view holds that zero-coded, or stem forms, of creole verbs have “several different and quite distinct functions” than overtly-coded forms (Bickerton, Reference Bickerton1975:26). Variationist studies, on the other hand, have shown that “a number of grammatical markers typically alternate with zero in a number of the subsystems of [creole grammars]” (Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack and Tagliamonte1999:193; cf., Meyerhoff, Walker, & Daeszynska, Reference Meyerhoff, Walker and Daleszynska2009; Patrick, Reference Patrick1999: Chapters 6 and 7; Rickford, Reference Rickford, Denning, Inkelas, McNair-Knox and Rickford1987:390; Sankoff, Reference Sankoff1990; Walker, Reference Walker2010; Weldon, Reference Weldon1996; Winford, Reference Winford1992).

Although the variable interplay between overt and zero marking has been the focus of several studies, it is still noteworthy that “the debate about the typological status of creole languages has severely suffered from a lack of systematic empirical study” (Bakker, Daval-Markussen, Parkvall, & Plag, Reference Bakker, Davall-Markussen, Parkvall and Plag2011:6). What happens, though, when we combine typological insights with the empirical rigor of the variationist method and then apply our findings to the Creole Debate? For example, typological studies report that there is a strong crosslinguistic tendency for habituals, whether they are overtly or zero coded, to develop through grammaticalization and in accord with specific markedness constraints (see the next section for a definition of markedness) (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985:52, 53; Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994:245–8; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151–60). Do these broad findings apply to habitual marking in creoles? If so, how can they be tested using language specific data?

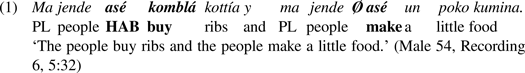

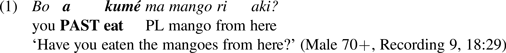

The current study brings quantitative methods to bear in order to test the applicability of crosslinguistic generalizations found in functional-typological literature. Specifically, I investigate whether Palenquero Creole, which has an emerging complex of preverbal forms and rampant zero-coded (bare) verb stems, conforms to presumed universals of typological markedness. Under the microscope are two linguistic variants—asé and zero—which are competing for dominance as habitual markers. In example (1), we observe that preverbal asé and a zero-coded verb stem may covary in the same (present) habitual context.

This situation is “habitual” because the interviewee was describing a particular annual festival wherein the locals customarily buy and prepare certain types of food as part of their tradition for that event. This paper addresses the following research questions:

• How is habitual meaning asymmetrically expressed across present and past tense—by the preverbal morpheme asé, or by a zero-coded (bare) verb stem?

• To what degree does the linguistic patterning of these forms conform to well-attested universals of typological markedness? How is habitual marking situated within the overall architecture of present and past temporal reference?

To answer the first question, quantitative analyses were conducted on more than two thousand tokens (total n = 2,543) of past and present temporal reference forms in order to implement a methodology to test previously established diachronic research for habituals (Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151–60). I considered two measures: to what extent does a given form actually express a given function, and to what extent is each function associated with any of the forms expressing it (Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack, Tagliamonte, Baker and Syea1996). The first measure would be the probability of speakers using asé or a zero-coded form in a habitual (relative to another) aspectual context, that is, the propensity of asé or zero to express habitual (as opposed to another) function. The second measure would be the absolute probability of speakers using asé, that is, the proportion of tokens of habitual meaning that appear with asé (as opposed to zero). As stressed by Poplack (Reference Poplack, Heiko and Heine2011:213), these measures, or form-function asymmetry, need not be coterminous.

To answer the second set of questions, the distributions of asé and zero are explained in light of strong crosslinguistic tendencies observed in the development of habituals, that is, asymmetries found in the expression of habitual grammatical expressions, or grams, across the present and past temporal reference domains. It is claimed that these asymmetries are manifestations of typological universals (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151; Croft, Reference Croft2003:87–8). By using the comparison of patterns in the past and present tense as a proxy for these diachronic tendencies, I test hypotheses regarding the trajectory of habitual development. Crucially, the way form and function are distributed and encoded across the temporal domains will also speak to Palenquero's typological status.

The results show that both asé and zero closely align with crosslinguistic predictions for habituals and give convincing evidence of typological markedness. Importantly, it was found that, despite Palenquero having widely cited creole features (e.g., preverbal markers and bare verb stems), this has no bearing whatsoever on the expression, distribution, or relative ordering of forms in the variable contexts as viewed from a typological markedness perspective.

The paper is organized as follows: the subsequent section discusses habitual and zero marking from a typological markedness perspective; next, I provide a sketch of the preverbal morphemes and postverbal suffixes in Palenquero; then I present the community, corpus data, and methods employed for this study; the following section presents the quantitative analysis of asé and zero as competing habitual markers in present and past tense; the last section takes a panoramic view in order to compare habitual markedness patterns with those found for progressive and state contexts; and finally, I state my conclusions.

Theoretical Considerations: Habituals, zeros, and typological markedness

Habitual marking

Broadly, habitual refers to any situation that is characteristic of an entire period of time or that is repeated on several occasions over a period of time (Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:27–8; Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:95). Studies in language typology and grammaticalization describe habitual meaning as being expressed crosslinguistically by an overt morpheme, or by no morpheme at all (Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151; Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:30; Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:100). Habituals often derive from erstwhile lexical verbs meaning ‘live’ and ‘know’ (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:154). In some languages, such as English, present habituals do not have a lexical source, but are derived through inference after the development of a progressive morpheme (Bybee, Reference Bybee2010:178-180) (see section on Zero marking, below). In Palenquero, habitual meaning is expressed by overt morphemes, the most frequent of which are asé and sabé, and which have the lexical sources (Spanish) hacer ‘do’ (Smith, Reference Smith, Narrog and Heine2018:382) and saber ‘know,’ respectively, and by a zero morpheme (Schwegler & Green, Reference Schwegler, Green, Holm and Patrick2007:275, 280, ftn.).

Typological markedness and habituals

“The essential notion behind typological markedness is the fact of asymmetrical or unequal grammatical properties of otherwise equal linguistic elements” and the apparent causal relationship between these elements and “how function is encoded into grammatical form” (Croft, Reference Croft2003:87–8). Markedness values are determined by comparing two paradigmatic alternatives, such as present and past tense, singular and plural number, or male and female gender, where one of the values is unmarked relative to the other one. In formal terms, markedness is measured by structural coding and distributional potential; thus, the unmarked value of a conceptual category will have no more morphological coding than the marked value and it will also be more frequent (Croft, Reference Croft2003:89–90).

For verbal categories, markedness asymmetries correlate with the distinct default meanings of present versus past tense. A default meaning is one that “is felt to be more usual, more normal, less specific than the other” (Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:111; cf., Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:19; Schwenter & Torres Cacoullos, Reference Schwenter and Torres Cacoullos2008:1–2). For example, the default meaning of present tense is not deictic, nor is it to signal an action ongoing at speech time (i.e., progressive), but, rather, to tell “how things are” (Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994:244; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151–3); therefore, present states and habituals, which perdure over time, are consistent with this meaning, and are unmarked members of this conceptual domain. To signal this relationship, they often have less morphological coding, more zero expression, and are more frequent than present progressives, which are anchored to the moment of speech, and, therefore, are the unexpected, or marked, members of the category. By contrast, the default meaning of past tense is to narrate completed events, or to tell “what happened” (Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994:244; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:158); thus, the presence of a habitual morpheme in this domain is marked, or unexpected, and therefore will contain at least as much, if not more, phonetic substance than perfectives or present habituals. These asymmetrical properties of habitual morphemes are not limited to synchronic states but are also related to processes of grammaticalization (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151).

Crosslinguistic studies suggest a clear relationship between developing habitual grams and typological markedness. As suggested above, one important discovery has been that “habitual is not a homogeneous piece of imperfective, but is highly affected by tense” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151). One reason for this asymmetry is that habitual grams begin their development in the past tense first before gradually extending to the present tense. Further, as they “pass through” temporal domains, forms are affected by markedness constraints imposed on them by their environments. Thus, we would expect Palenquero habitual morphemes to show markedness patterns consistent with the domains—present versus past—in which they occur. By contrast, any anomalous behavior must be explained outside of typological markedness theory.

Zero marking

Zero morphemes express meaning, though they are not overt markers nor do they derive from one (Bybee, Reference Bybee2010:177, 180). In this paper, I distinguish between zero-coded morphemes that express open meanings, that is, meanings that overlap with overt morphemes, and zero-marked forms, whereby zero is the opposition of some overtly coded form (Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994). In contrast with open zeros, obligatory zero marking happens late in the grammaticalization process of an overt morpheme, which, after taking over one of the meanings once encoded by an older, zero-coded form, leaves zero as its opposition (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985:27; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:239; Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack, Tagliamonte, Baker and Syea1996:90).Footnote 1 A clear example of this taking place is the development of the present progressive in English (be + verb + -ing), which left bare verb stems that previously expressed both progressive and habitual functions to only mark habitual.

Typological markedness and zeros

Typological studies reveal that zero morphemes, like overt morphemes, are not randomly distributed over semantic space; rather, there exist systematic irregularities, which are manifestations of typological universals (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985:53–5; Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994; Croft, Reference Croft2003:92; Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1966). For example, it is predicted that certain meanings may never have zero expression, such as past habituals and progressives, while others can, such as general presents, present habituals, and past perfectives (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:52, 91–2, 131, 144, 151), given the default interpretation of the temporal conceptual domain in which they appear. Crosslinguistic studies variably correlate zero expression with present, but not past, habitual meaning (e.g., Bybee, Reference Bybee1985:53–4; Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151). For Palenquero, it is expected that there would also exist an asymmetrical, but predictable, coding of zero morphemes, as for overt morphemes, according to these typological universals (Smith, Reference Smith, Narrog and Heine2018:374).

Zero marking and creoles

During their nascency, creole languages do not develop zero morphemes in the ways mentioned in the preceding section (Sankoff, Reference Sankoff1990:295, 310). In these languages, the inflectional systems of the donor languages are often lost during creole genesis/formation, thus creating a lot of zeros in the process (Arends & Bruyn, Reference Arends, Bruyn, Arends, Muysken and Smith1995:116). Thereafter, overt morphemes are said to develop out of communicative necessity (Bryun, Reference Bryun, Baker and Syea1996:30). Additionally, zero-coded forms may transfer from a creole's super- or substrate languages. The plethora of zeros present during the earliest stages of creolization would be, in fact, zeros with open meanings, since their opposing tense-aspect forms would not have had time to develop (Sankoff, Reference Sankoff1990). There is no way of knowing how robust zero morphemes were during Palenquero's earliest stages of development. We do have, however, the current distributions of zero and overt morphemes across several contexts (Smith, Reference Smith, Carvahlo and Beaudrie2013, Reference Smith2014). The next section presents a sketch of the overt preverbal and postverbal forms.

Preverbal morphemes and suffixes in Palenquero

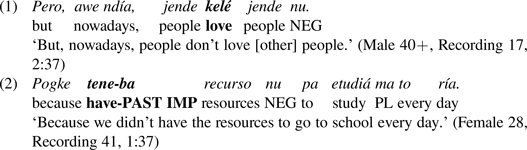

Palenquero has several preverbal morphemes with tense-aspect functions: asé (habitual), sabé (habitual), ta (progressive), a (past perfective/completive; in present unknown function); and two suffixes: -ndo (progressive), and -ba (past imperfect).

Traditional descriptions label asé as the primary marker of habitual aspect (Bickerton & Escalante, Reference Bickerton and Escalante1970:258; Holm, Reference Holm1988:149; Moñino, Reference Moñino2000; Schwegler, Reference Schwegler, Michaelis, Maurer, Haspelmath and Huber2013; Schwegler & Morton, Reference Schwegler and Morton2003:151). Asé is a general habitual morpheme, that is, one that is not limited by tense but occurs in both present and past tense (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151). Scholars have observed that other forms, such as preverbal sabé and zero-coded stems, may also express habitual meaning. For example, Schwegler and Green (Reference Schwegler, Green, Holm and Patrick2007:279) stated that, while habitual is “often not overtly expressed” in Palenquero, “the most common means of expressing habitual aspect is asé” (Schwegler & Green, Reference Schwegler, Green, Holm and Patrick2007:280).

Variationist studies on Palenquero asé report that, in the present tense, asé is not an obligatory or exclusive marker of habitual meaning but is in fierce competition with zero (Smith, Reference Smith, Carvahlo and Beaudrie2013). Sabé, on the other hand, occurs very infrequently as a habitual morpheme (Smith, Reference Smith, Carvahlo and Beaudrie2013:105). Additionally, it has been found that zero, while it does not represent the opposition of any overt morpheme, is such that “there are discourse-pragmatic preferences for zeros such as with copula verbs, statives, and in habitual contexts with non-stative verbs” (Smith, Reference Smith, Carvahlo and Beaudrie2013:107). Several other factors have also been found to constrain asé variation, such as stativity, aspectual meaning, and polarity (Smith, Reference Smith, Carvahlo and Beaudrie2013, Reference Smith, Narrog and Heine2018).

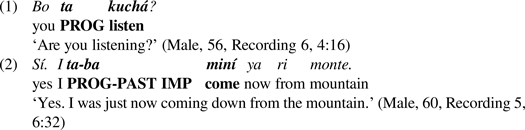

In the past tense, preverbal asé may variably combine with the past suffix -ba across the verb phrase to express habitual meaning (Schwegler, Reference Schwegler1992:224; Schwegler & Green, Reference Schwegler, Green, Holm and Patrick2007:280). As it does with preverbal auxiliaries (e.g., kele-ba ‘wanted’, pole-ba ‘was able to’) and other aspectual morphemes (e.g., ta-ba [PROG], sabe-ba [HAB]), suffixed -ba may attach either to preverbal asé (e.g., I ase-ba kumé ‘I used to eat’), the main verb (e.g., I asé kume-ba ‘I used to eat’), or to both the preverbal particle and the main verb (e.g., I ase-ba kume-ba ‘I used to eat’) (Davis, Reference Davis2000:567; Lipski, Reference Lipski2012:109–11). Early on, -ba was thought to be an anterior (i.e., remote past) marker (Lewis, Reference Lewis1970:115); however, more current analyses have shown that it is a past imperfective marker (Davis, Reference Davis1997, Reference Davis2000; Lipski, Reference Lipski2012; Schwegler & Green, Reference Schwegler, Green, Holm and Patrick2007:276; Smith, Reference Smith2014:106).

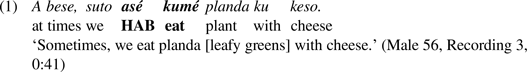

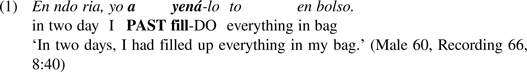

According to Schwegler and Green (Reference Schwegler, Green, Holm and Patrick2007:279), asé may be omitted when habitual meaning is already clear from the context, such as when there is an explicit asé present. Example (2) shows preverbal asé with past temporal reference covarying with a bare verb stem combining with the imperfective suffix -ba. This example raises the issue of whether the verb entraba is zero coded because the first asé has scope over the entire utterance, or if -ba alone has habitual functions, as it can in Spanish. In example (3), we see a past tense bare verb stem with no coding at all, preverbal or otherwise (meté). In this example, the bare stem is preceded by a coordinating verb (pasá) that has an explicit asé; this, along with the -ba case in (2), raises empirical questions about whether marker absence is restricted to cases of the presence of an explicit asé-marked habitual. This paper will be a first look at past tense zero marking on Palenquero habituals. We now turn to our main focus which is typological markedness as it relates to habitual expression. I begin with a brief outline of the community, the corpus, and data coding methods.

The Community, Corpus, and Data Coding

The community

The Afro-Hispanic village of San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia (or, Palenque) is located some 70 km (43 miles) southeast of Cartagena de Indias. It was once a maroon community formed by enslaved people who escaped from bondage between 1655-1674 (Navarrete, Reference Navarrete2008:70). Currently, some 4,000 residents speak Palenquero Creole, or Lengua, a language with origins in Spanish and Kikongo. Its status as a creole is without question, though it was only identified as such around 1970 (Bickerton & Escalante, Reference Bickerton and Escalante1970; Granda, Reference Granda1968). The attraction of the world of scholars to Palenque is in direct relation to the “discovery” that the Palenqueros speak a bona fide creole language (Lipski, Reference Lipski2005:287, ftn.). However, due to widespread prejudice and discrimination from Colombians in the surrounding cities and towns, Palenqueros stopped speaking the language in public settings and at home, resulting in a break in intergenerational transmission among its speakers. In a fortuitous turn of fate, in 2005 San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia was declared a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO. This recent global attention has spawned language revitalization programs, activism, and education at the community level, and, as a result, the language has experienced a remarkable resurgence.

The corpus and participants

The data for this study were taken from The Bilingual Corpus of Palenquero Creole: San Basilio de Palenque, Cartagena, and Barranquilla, Colombia (Smith, Reference Smith2011-2014), a collection of sociolinguistic interviews conducted by the author throughout extended visits to the community from 2011 to 2014.Footnote 2 The sociolinguistic interview is a set of loosely structured dialogues that are designed to tap into the vernacular, which is now known to be the most structured of an individual's total speech repertoire (Labov, Reference Labov, Baugh and Sherzer1984:29). The consultants were thirty fluent adult speakers of Palenquero, males (n = 15) and females (n = 15), whose ages ranged from twenty-one to eighty-eight. Participants were selected with the aid of community members, who often participated in, and conducted, many of the interviews. At this time, I would like to express my gratitude for the hard work of my guides and participant observers, Rosalio Salgado, Florentino “Niño” Estrada, Ángel Valdez Herazos, Luís Hender Martínez, and Walberto Torres Pérez.

The recordings were transcribed using the transcription software program Elan (Lausberg & Sloetjes, Reference Lausberg and Sloetjes2009). For the current study, a total of ten hours (twenty minutes per participant) of audio recordings were transcribed by the author and reviewed by native and heritage Palenquero speakers who received training in sociolinguistics and transcription methods over the course of many months. A valuable feature of the present corpus is that long, uninterrupted, twenty-minute blocks of free-flowing speech were transcribed in their entirety, not selected paragraphs or small snippets (Poplack & Dion, Reference Poplack and Dion2012:280). The corpus, as it was not designed around specific linguistic features or research questions, has widespread usability and can serve as a language archive (cf., Torres Cacoullos & Travis, Reference Torres Cacoullos and Travis2018:39–49). I would like to thank Basilia Pérez Márquez, Juana Paula “Pavi” Tejedor, Estilita María Cassiani Obeso, and Cristina de la Hoz Márquez for their invaluable assistance with the transcription work.

Data coding: aspectual meaning

In addition to habitual, the data were coded for the following aspectual meaningsFootnote 3 that were found in the present and past temporal reference domains: nonstative predicates were coded as progressive, frequentative, perfective, perfect, or remote past; stative predicates were also included as a separate category.

Progressive

A progressive action takes place simultaneously with the moment of reference (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:317). Examples (4) and (5) illustrate present and past progressive, respectively.

Frequentative

A frequentative action occurs frequently, but not necessarily habitually (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:317). Frequentative can be viewed as a subset of habitual but whose meaning is more specific and from which more general habituals develop through grammaticalization (170). Example (6) was coded as frequentative due to the presence of the temporal adverbial a bese ‘sometimes.’

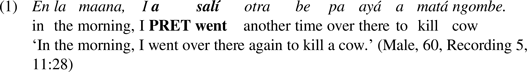

Perfective

Perfective aspect signals that a situation is construed as being bounded temporally or views a situation as a whole. Perfective aspect is used for narrating sequences of discrete events, and therefore, typically refers to situations in the past. (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:317; Comrie, Reference Comrie1976:16).

Perfect

Perfects are relational and their meaning “signals that the situation occurs prior to reference time and is relevant to the situation at reference time” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:54).

Remote past

Remote past indicates “a situation occurring temporally distant from the moment of speech” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:317).

State

“States characterize situations for a period of time that includes, but is not necessarily restricted to, the present moment.” It is claimed that the principal difference between habituals and states is minimal and that the difference between the two meanings “lies entirely in the lexical meaning of the predicate” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:152). Example (10) illustrates a present state and example (11) illustrates a past state.

The variationist method

The variationist method was used to uncover distributional patterns (Labov, Reference Labov1966). A key facet of this approach is the principle of accountability, which requires that we count every place where the variant under investigation occurs but also where it could have occurred but did not (Labov, Reference Labov1972:72). The variable context is defined as the largest domain within which variation of a particular set of variants can occur. Appropriately circumscribing the envelope of variation is always the goal; however, the theoretical rationale behind coding decisions is not always spelled out, as has sometimes been the case, for example, with past temporal reference contexts in African American English and Caribbean English Creoles (Hackert, Reference Hackert2008). For the current study, the variable contexts were chosen because they specifically test theories of grammaticalization and markedness that implicate developing habitual morphemes (e.g., Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994; Croft, Reference Croft2003; cf., Poplack & Tagliamonte, Reference Poplack, Tagliamonte, Baker and Syea1996; Walker, Reference Walker2001).

To that end, I appropriated all preverbal and zero-coded forms that appeared in the broad domains of present and past tense (Ø, a, asé, sabé, ta). The tokens (n = 2,543) were exhaustively extracted from the transcriptions and analyzed using Goldvarb X (Sankoff, Tagliamonte, & Smith, Reference Sankoff, Tagliamonte and Smith2005). For present tense, a second variable context was defined: alternating asé versus zero with states and habituals. For past tense, the preliminary results revealed that no further regression analyses could be conducted. I discuss both results in turn now.

Analysis: Habitual marking in present tense

Overall distributions

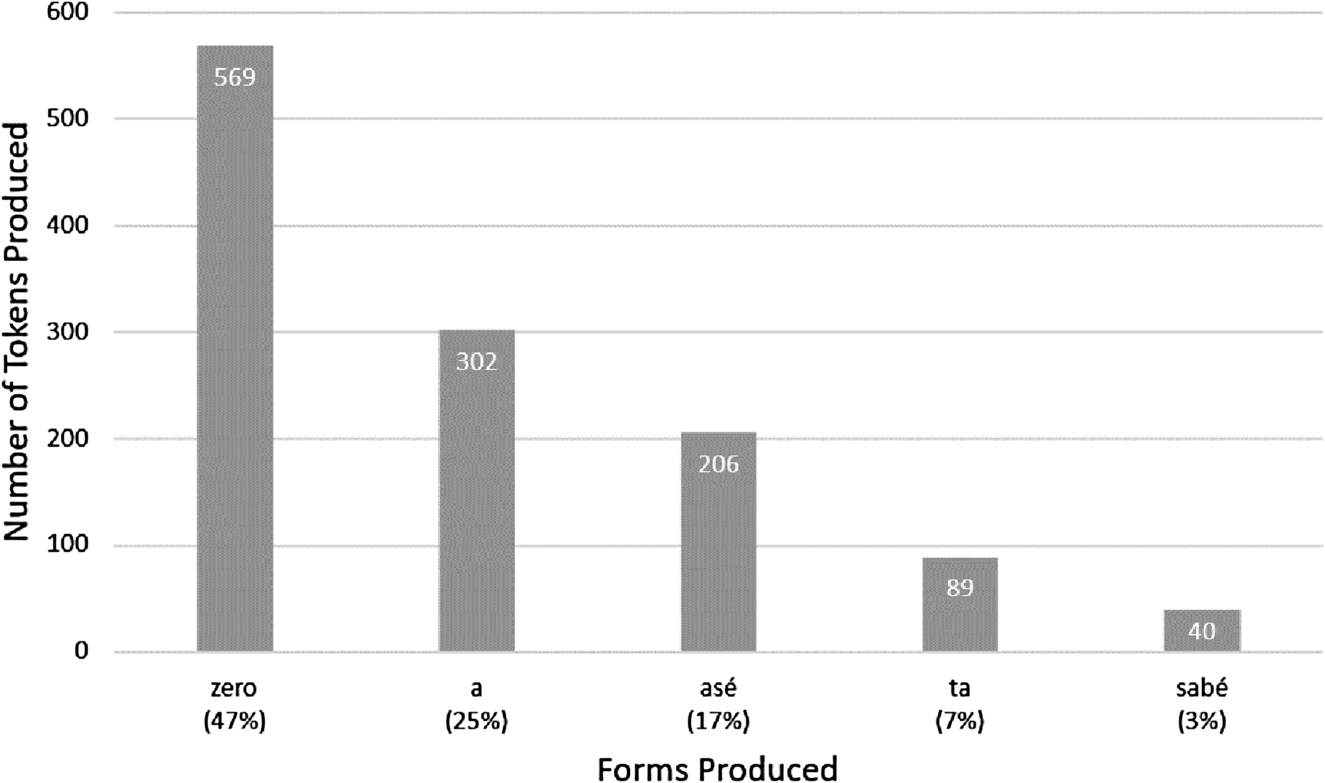

Figure 1 presents the overall distributions of aspectual forms in present temporal reference. We observe that zero-coded verb stems are more frequent than any one preverbal morpheme, as they take up nearly half of the data (47%, n = 569/1,206); preverbal a is the second-most frequent (25%, n = 302/1,206); asé ranks third (17%, n = 206/1,206); followed by ta (7.4%, n = 89/1,206) and sabé (3.3%, n = 40/1,206). Although the prominence of zeros is attention grabbing, it is actually form-function asymmetry that is most elucidating in terms of habitual expression. In what follows, the relationship between habitual meaning and its formal expression is explored.

Figure 1. Overall distribution of preverbal forms in present temporal reference in Palenquero Creole (n = 1,206).

Form-function asymmetry in present tense with a focus on asé and zero

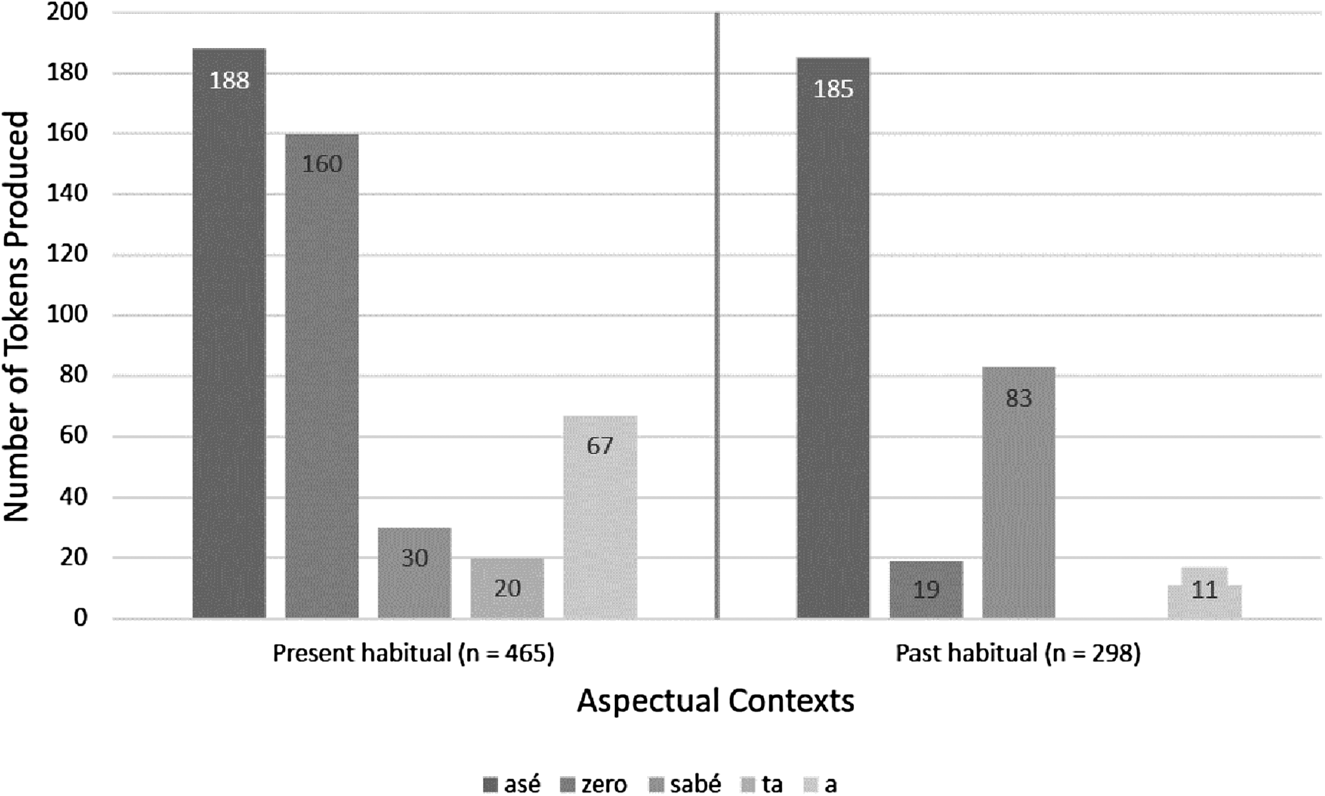

The accountability principle requires that we correlate habitual meaning and all available present tense forms. For that reason, the first variable context was exploratory, being circumscribed as the broad domain of present temporal reference. Figure 2 displays the distributions of preverbal and zero-coded forms across aspectual contexts: state, and for dynamic verbs, habitual and progressive. As seen in the graphic, the data do not reveal one-to-one form-meaning pairings; instead, form-function asymmetry is confirmed for all forms and meanings.

Figure 2. Distribution of aspectual meanings in present tense across preverbal forms (n = 1,186).

We observe that zero morphemes have open meaning; that is, state, habitual, and progressive meanings may all be expressed by a bare verb stem. Note that all five preverbal morphemes (asé, zero, a, sabé, and ta, respectively) may express present habitual meaning to varying degrees; however, it is primarily expressed by asé and zero compared to any of the other choices at a speaker's disposal. Habitual meaning is coded with asé 40% of the time (n = 188/465) and is zero coded one-third of the time (34%, n = 160/465), thus, establishing them as the two main competitors vying for habitual space (75%, n = 348/465) in the present reference temporal domain. It is noteworthy, however, that 60% of the time habitual meaning is not expressed by asé, but by some other means. This is interesting in light of the fact that the form asé itself is far more likely to express habitual over some other meaning (92%, n = 188/203). These last two facts, when taken together, highlight an important point regarding form-meaning pairings—they are not coextensive in scope (Poplack, Reference Poplack, Heiko and Heine2011:213).

The overall patterning of the data is consistent with crosslinguistic observations made about the architecture and function of present tense. For example, states (at 53%, n = 625) and habituals (at 38%, n = 456) together make up over 90% of all aspectual possibilities, which confirms the crosslinguistic observation that the default meaning of present tense is to simply express “how things are” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:153). Also consistent with crosslinguistic trends is that present progressive morphemes are quite infrequent (Bybee, Reference Bybee2010:180), making up only 8% of the data (n = 96/1,186).

The distributions of zero morphemes (the bottom bar in the stacked column graph of Figure 2) also accord with typological predictions for present tense, such that progressive aspect has higher proportions of overt coding (all nonbottom bars) than states and habituals, which show higher proportions of zero-coded verb stems. Hierarchically, zero makes up a greater proportion of states (60%, 373/625) than of habituals (34%, 160/465) and even less of progressives (24%, 23/96). We also observe that the smallest morpheme a is the second-most frequent way to express state meaning (36%, 227/625), after zero. Not to be overlooked is the fact that present progressives, in addition to being overtly coded more often, have more phonetic material than overtly-coded states and habituals, as they can be expressed by the preverbal particle ta and/or the suffix -ndo. This is because progressives are typologically marked in this environment.

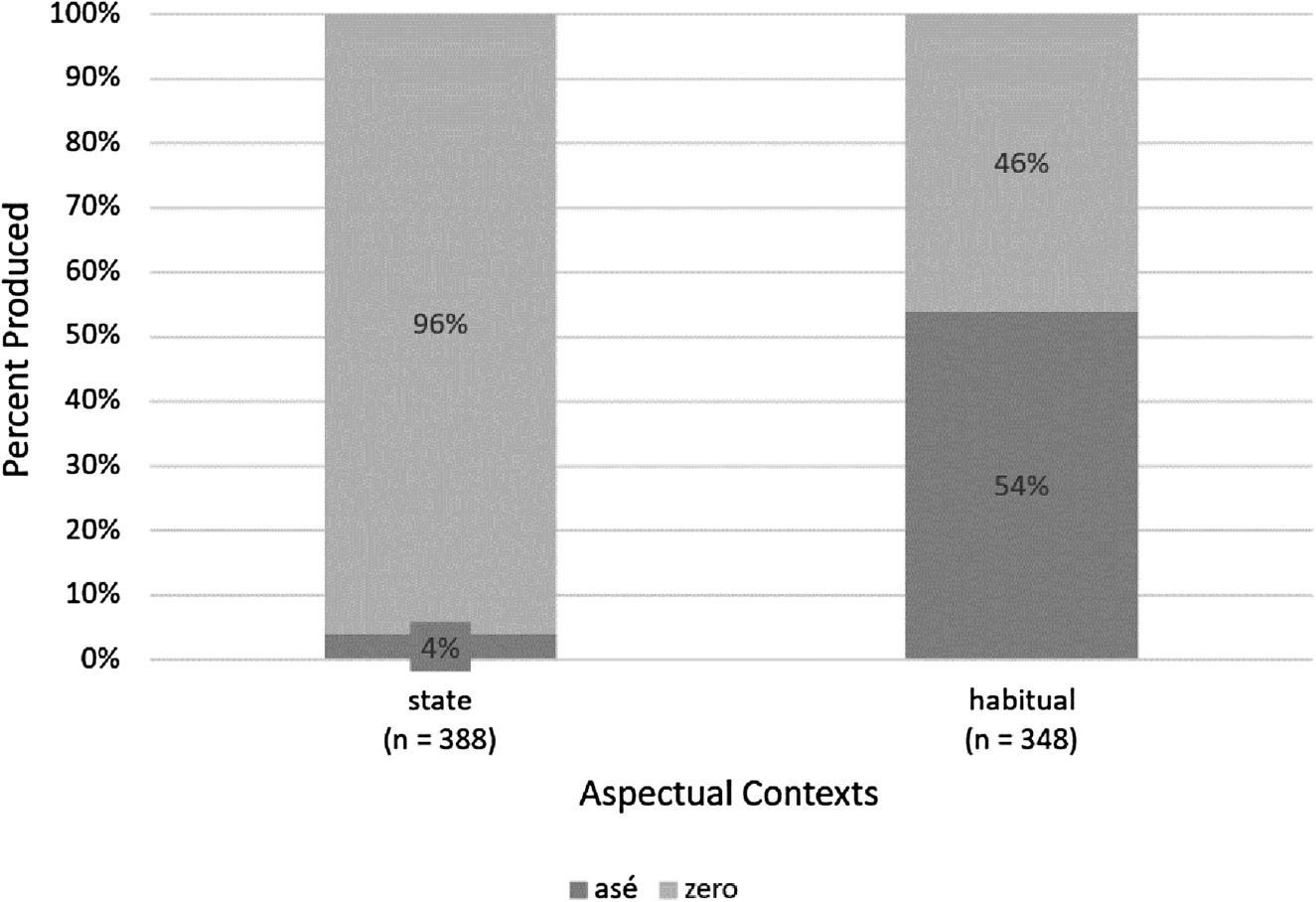

Analysis: narrowing the envelope to asé versus zero

The second variable context was restricted to asé versus zero in state and habitual aspectual contexts, the two most frequent present-tense domains (n = 736). The overall rate of asé is 28% (n = 203/736) compared to zero. As seen in Figure 3, asé is favored in habitual contexts, where it occurs 54% of the time (n = 188/348), whereas state contexts are the stronghold of zero (94%, n = 373/388). A zero morpheme being a major contender with an overt morpheme in terms of frequency is consistent with predictions for habituals in present tense. However, one might also expect to see a zero morpheme favored in this environment, since habitual is one of the default readings of present tense and since zero expression is often associated with basic members of conceptual categories (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985:52). Do these results present a challenge to typological markedness? No.

Figure 3. Percentage of asé versus zero in state versus habitual contexts (present tense) (n =736).

First, it is still unclear how widespread zero-marked habituals are crosslinguistically given the typological data available; nevertheless, it appears that overtly coded habituals are more frequent crosslinguistically than zero-marked ones, though they are consistently less marked in present than past (Bybee, Reference Bybee1985:52; Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151; Dahl, Reference Dahl1985:95–6). For this reason, there is no a priori reason why creoles should not have overt habitual expression in the present tense as do other languages. Second, in these data, zero predominates in state contexts more than it does in habitual ones; so, although existing states and habituals are both part of the default meaning of present tense, it appears that, given the distribution of zeros, present state may be the more basic of the two meanings. We find, then, that although there are similarities between stative and habitual meanings, there are clear differences in how they are coded even with respect to the same morphemes (cf., Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:152). This patterning relates to the overall tendency for statives to be zero coded more than other present tense aspectual categories.

Considering verbs according to their lexical aspect, when asé versus zero were compared in the subcontext of nonstative (dynamic) verbs, the overall likelihood of asé to occur as opposed to zero was higher, at 49% (n = 376/735) (Smith, Reference Smith, Carvahlo and Beaudrie2013:106). In this subcontext, there is a clear tendency for asé to be favored with frequentatives (93%, 13/14), whereas with habituals asé shares the space with zero (52%, n = 91/175).

These data show many patterns consistent with typological markedness in present tense. However, as discussed earlier, an unmarked value is established only in relation to its paradigmatic alternative (Croft, Reference Croft2003:90). We now turn to the distributions in past temporal reference.

Analysis: Habitual marking in past tense

Overall distributions

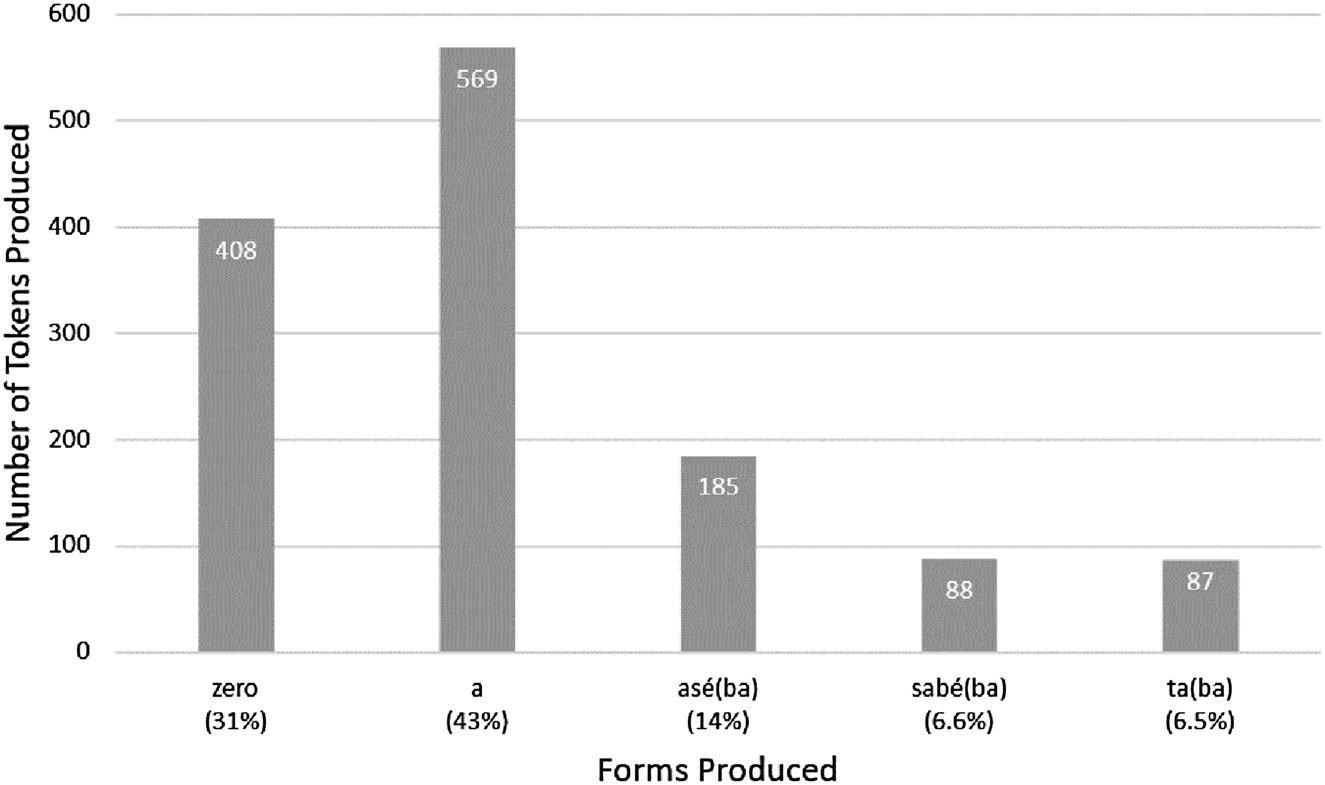

Figure 4 presents the overall distribution of aspectual forms with past temporal reference. In this context, the preverbal form a, the marker of perfective (and related meanings), is the most frequent of all the aspectual forms (43%, n = 569/1,337). Next are zero-coded verb stems, which make up 31% (n = 408/1,337) of the data. The remaining 27% (n = 360/1,337) is distributed among imperfective morphemes, such as asé, which accounts for 14% (n = 185/1,337) of the overall data, and sabé and ta, which make up 6.6% (n = 88/1,337) and 6.5% (n = 87/1,337), respectively. When we compare asé and zero only (total n = 593), we find that the relative frequency of preverbal asé compared to zero is 31% (n = 185/593). In what follows, the relationship between habitual meaning, which is a marked aspectual category in this domain, and the consequences for its formal expression, are explored.

Figure 4. Overall distribution of tense-aspect forms in past temporal reference (n = 1,337).

Form-function asymmetry in past tense with a focus on asé and zero

As was the case for present temporal reference, the first measure was to determine correlations between the preverbal and zero-coded forms and their respective functions. The variable context was circumscribed as the broad domain of past temporal reference, which consisted of perfective and related meanings (perfect and remote past), states, progressives, and habituals.

Figure 5 shows the distributions of aspectual distinctions by preverbal and zero-coded forms.Footnote 4 First, we observe that the preverbal morpheme asé is confined to habitual meaning, expressing that meaning 100% of the time (n = 185). By contrast, habitual meaning itself is expressed by asé tokens only 62% of the time (n = 185/298), thus confirming form-function asymmetry. The rest of the habitual domain is made up of sabé (28%, n = 83/298), and less frequently by zero (6%, n = 19/298), and a (4%, n = 11/298), but never by the progressive morpheme ta, as in present tense. These distributions reveal an important fact about habitual expression: for present tense, asé and zero were the main candidates vying for habitual space; whereas, in the past tense, asé and sabé—not zero—are doing most of the habitual work.

Figure 5. Distribution of aspectual meanings in past tense across preverbal forms (n = 1,327)Footnote 6.

Past reference zero morphemes are doing different work, and a different amount of work, compared to zeros in the present tense. In some cases, a past zero morpheme represents one of only two options available to express a conceptual category, such as perfective, perfect, and remote past meanings (which are collapsed in Figure 5). In other cases, zero competes with several preverbal morphemes, as with habitual, state, and progressive meanings. One marked similarity between past and present tense bare verbs, though, is that in both cases a zero preverbal morpheme is most closely associated with existing states, though no such symmetry exists between zero coding and habituals across tense (cf., Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:152).

In fact, there were very few cases of verb stems expressing habitual meaning that contained only the -ba suffix (n = 6) (see section above on Palenquero verb forms) or no coding at allFootnote 5 (n = 13). Striking was that all examples in the sample had an explicit asé present in the immediate discursive context, as examples (2), (3), and (12)-(14) illustrate. So, in these instances, preverbal asé is either “deleted,” or simply not needed, when there is another asé present. When -ba co-occurs with asé in the verb phrase, its primary function seems to be to mark past tense, since habituality already entails duration. In some cases, it is unclear whether the verb stem suffixed with -ba is simply borrowed from Spanish (as with entraba in example [2]). In any case, given the small number of tokens, further analysis is needed.

The overall patterning of the data is consistent with crosslinguistic observations made about the structure and function of past tense. For example, the overwhelming majority of past tense predicates are nonstative verbs (75%, n =1,007), the vast majority of which express perfective meaning (n = 611). We observe that all perfective-related meanings (perfective, perfect, and remote past) are expressed only by the smaller morphemes a and zero; whereas, imperfective meanings such as habitual and progressive are primarily expressed by a bulkier morpheme (e.g., asé(ba), sabé(ba), and ta(ba)), which are, in turn, bulkier than their present tense counterparts, asé, sabé, and ta. This result coincides with the crosslinguistic tendency for perfectives to be zero coded, or at least to be less coded with respect to past habituals (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:245).

Past imperfectives were expected to always be overtly expressed (Bybee et al.,1994:154); therefore, the fact that there is zero expression at all may seem to contradict the logic of typological markedness. Yet, as these data show, there is a very strong tendency for past habituals to be overtly coded (94%, n = 279/298), and the few bare stems that do appear in these data are always found in the company of an overtly coded form. Given markedness expectations, to the extent that past habituals were ever truly zero marked at an earlier stage in Palenquero's history, I theorize that overt forms would have begun developing right away.

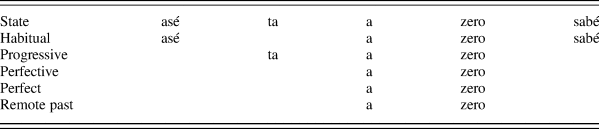

As schematized in Table 1, the size and number of morphemes expressed by aspectual categories in past tense suggest this markedness hierarchy (in ascending order): perfective-related meanings < progressives < habituals < states. In addition to being the smallest of the overt morphemes, we observe that a also has more distributional potential than all of the other forms, with the exception of zero, as it is distributed orthogonally across all aspectual categories. The data so neatly conform to markedness patterns for past tense, a regression analysis of asé versus zero could not be conducted. In configuring the data, it was not possible to exclude or combine groups for the Varbrul analysis in a linguistically sound way, because there were many *knockouts* or *singletons* in the factor group Aspectual Meaning. Though this situation presented methodological problems, it proved to be a boon for the hypothesis.

Table 1. Aspectual morphemes showing conformity to typological predictions

While these findings for habituals are impressive, it is important that they are put into a broader context. When the baseline habitual data are compared with progressives and states, we see a creole language that is in lock step with crosslinguistic markedness universals.

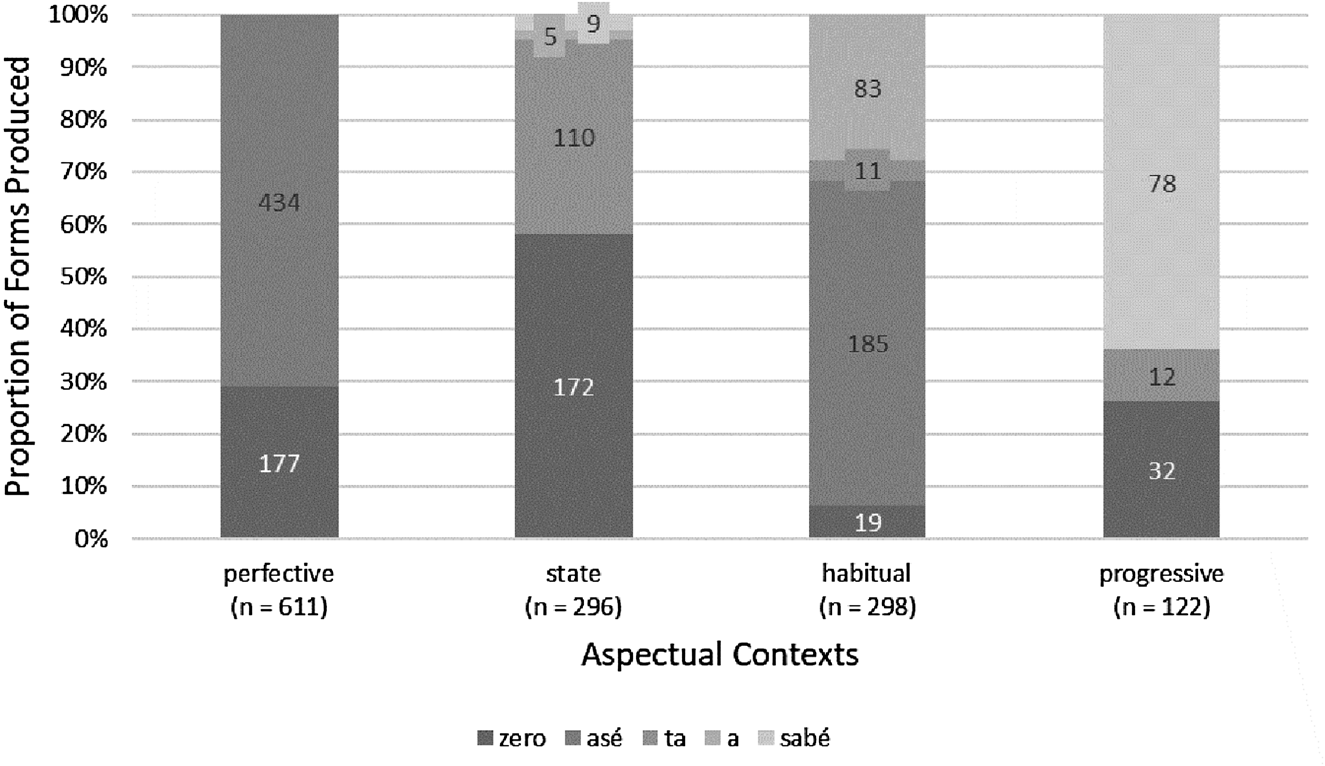

Comparison of typological markedness patterns of habituals versus progressives and states

Baseline: expression of habitual in present versus past

Figure 6 summarizes the discussion and establishes a baseline for comparison; it illustrates the typological markedness asymmetries in habitual expression across present and past tense. Habitual meaning is expressed by all five of the variants in present tense but by only four of the five in past tense. As we have discussed, zero coding is dramatically more frequent in the present than in the past. Smaller morphemes, such as a, play a greater role as habituals in the present, while larger morphemes, such as sabé, are ranked higher in the past. Though not seen in the graph, all habitual morphemes have more phonetic bulk in the past than they do in the present.

Figure 6. Side-by-side comparison of habitual morphemes in present and past tense (n = 763).

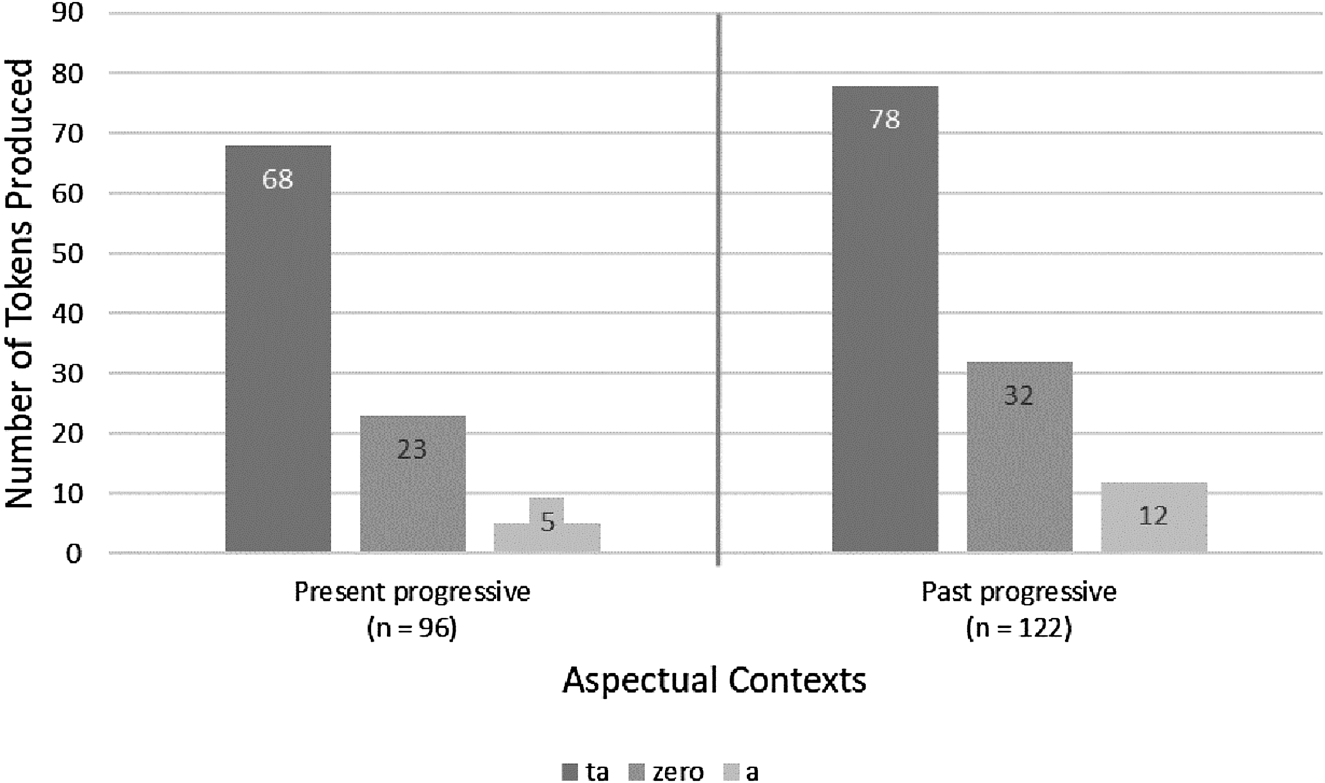

Comparison 1: expression of progressive in present versus past

Progressives (Figure 7) are equally marked across present and past tense. They are expressed by three morphemes (if you include zero), which occur in the same order and with similar relative (and absolute) frequencies. Given the greater phonetic bulk of past temporal reference progressives (compare examples 4 and 5), we can say that progressives are only slightly more marked in the past, since imperfectivity is less consistent with the default meaning of past tense than present tense. Also striking is the overall paucity of progressive morphemes (n = 218) compared to states (n = 922) and habituals (n = 763). Yet, present and past progressives are neck-and-neck in all other respects, which also makes sense, given that progressive meaning is not part of the default meaning of either past or present tense.

Figure 7. Side-by-side comparison of progressive forms in present and past tense (n = 218).

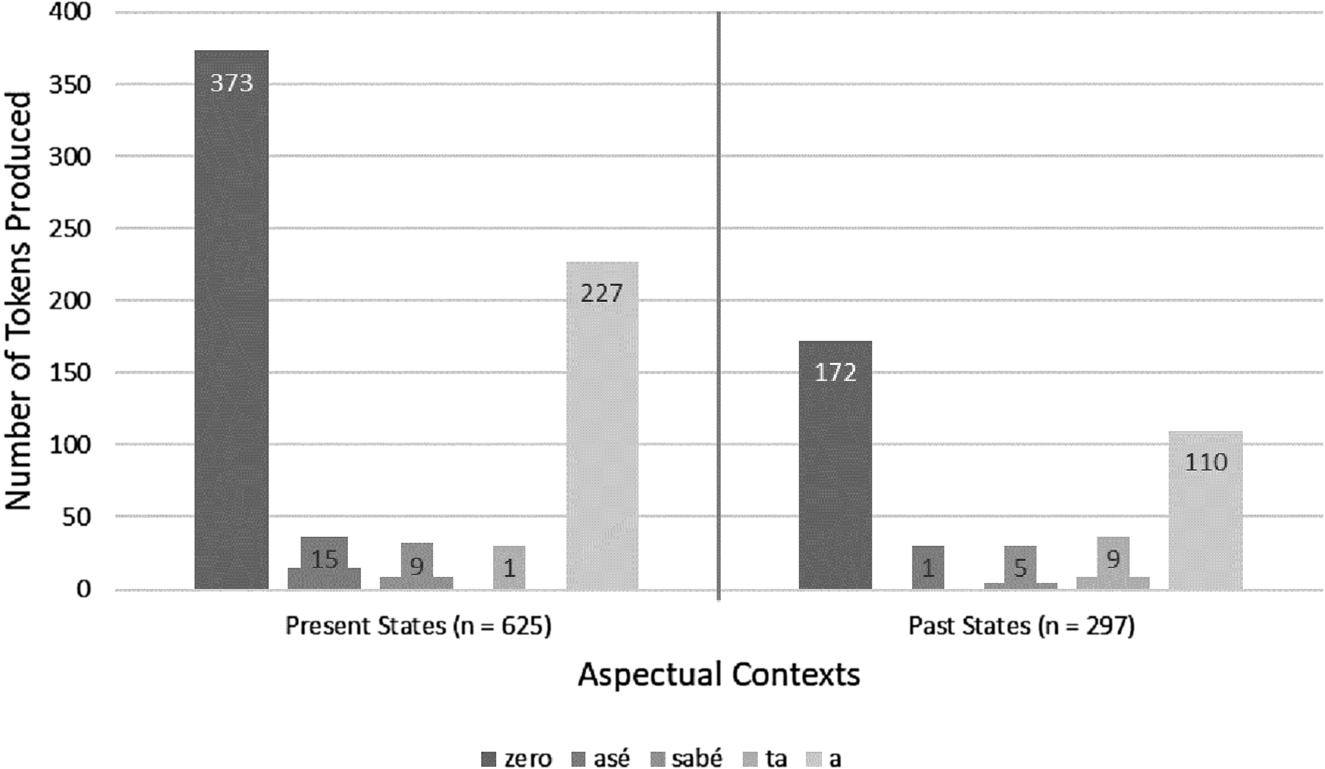

Comparison 2: expression of state exists in present versus past

States show very similar markedness patterns in present and past tense (Figure 8). For example, zero occurs at similar rates in both present (60%, n = 373/625) and past tense (58%, n = 172/297), followed by a, which also shows near equal rates of expression in present (36%, n = 227/625) and past (37%, n = 110/297), and the other three variants are negligible. States are expressed by the same amount of (and the same) morphemes across temporal domains; they are also expressed by the same morphemes as present habituals. This seems to be consonant with the similar meanings of states and habituals, but it also highlights clear differences between the two domains, because past habituals differ in distributional potential from present and past states and from present habituals (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:152). Additionally, the similarity in markedness patterning across present and past tense supports the claim that the default meaning of creole statives is “state concurrent with reference time” (Bybee, Reference Bybee and Pagliuca1994:251). As with progressives, we do find that past states have more morphological coding than present states (compare examples 10 and 11), and are thus slightly more marked in the past over present. In line with markedness predictions, the two habitual morphemes, asé and sabé, are more frequent than progressive ta in present state contexts, but the patterning of these three morphemes is reversed in the past. Also, and not surprisingly, states are more frequent in the present.

Figure 8. Comparison of state exists forms in past and present tense (n = 922).

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that Palenquero exhibits features that conform to broad typological patterns. In the present tense, asé and zero were the main contenders for habitual space. An analysis of state and habitual contexts revealed that asé was strongly favored over zero with habituals. However, in the subcontext of nonstative (dynamic) verbs, considering frequentatives versus habituals, the correlation between asé and habitual meaning was notably weak. The fact that zero was robust is because habitual is “one of the basic or default aspectual readings of present tense” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:191). However, given the closer association of zero with states than habituals, it may be that state meaning is the more congruous of the two with the default meaning. The distributions of present tense aspectual morphemes revealed this markedness hierarchy: states and habituals were more frequent, contained less overt coding, and more zero expression, than progressives (Figure 2). This finding upholds the insight from typological studies that the default meaning of present tense is to state “how things are.”

An examination of past tense revealed that asé and sabé were doing most of the habitual work. Zero, on the other hand, was more closely associated with perfectives and states, and only appeared a handful of times in past habitual contexts. There were only a few instances of verb stems that were coded only with the -ba suffix or that were truly bare. In each of those cases, habituality was made explicit in the immediate context. Overall, past habitual forms were typologically marked: they had more overt coding, hardly any zero expression, and were less frequent than perfectives and present tense habituals (Figure 5). This confirms that the entire structure of past tense is consistent with typological markedness predictions. In fact, the forms and functions were so well behaved that a binomial regression could not be conducted. The few anomalies that were found, such as zero-coded past habituals, do not contradict typological markedness, but can be explained by discourse pragmatics.

Finally, a comparison of habitual markedness patterns with progressives and states revealed that, while habituals showed asymmetries, progressives and states showed near equal marking across tense, being only slightly more marked in the past (Figures 6, 7, and 8). This finding confirms the crosslinguistic generalization that habituals are indeed “highly affected by tense” (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:151, emphasis mine) and that tense asymmetries are truly a hallmark of this conceptual domain.

In sum, these data overwhelmingly suggest that, in the domain of verbal categories, Palenquero Creole strictly adheres to typological markedness universals. These findings have implications for the Creole Debate. In this case, since creoles are often typologized based on their structural properties, it was important to look not only at structure (i.e., +, − preverbal markers), but at the close relationship between form, distributions, and external function. In fact, it was form-function asymmetry that allowed us to discern markedness patterns in the expression of habitual meaning.

However, Palenquero's compliance to typological universals is not limited to the verbal domain. A recent study of number marking found that the prenominal plural marker ma was favored with plural count nouns that were both specific and in subject position, while bare nouns were favored with nonspecific objects. These results are consistent with a discourse-typological framework, as there is a well-attested correlation between valency, discourse/information flow parameters, and morphological coding (Cassiani Obeso & Smith, Reference Obeso, María and Smith2020). These findings, when considered together with the results from the current study, suggest that assertions made about a creole's typological status, instead of encompassing the entire grammar, may be better stated in terms of one feature over another.

Of course, some creole grammatical features may pattern differently from crosslinguistic trends along some qualitative or quantitative dimension, in which case explanations for these anomalies need to be sought. That said, observed deviations need not be judged immediately to be indications of a creole prototype, as there may be discourse-pragmatic factors at work that do not contradict the logic of typological markedness (as was the case with zero-coded past habituals), as well as social or other considerations to be factored into the analysis.

Crucially, the methods employed in addressing longstanding questions regarding the typological status of creole languages constrain the outcome of any analysis. For example, some researchers have used statistical modeling and computational tools of quantitative typology to compare clusters of creoles to other languages (Bakker, Daval-Markussen, Parkvall, & Plag, Reference Bakker, Davall-Markussen, Parkvall and Plag2011). However, in this approach creoleness (as measured by simplicity, similarity, and degree of language mixing) is defined by modeling the clustering of broad structural features already associated with creoles. The result was that these authors came to an entirely different conclusion than the one stated in this paper. In contrast, the current study took a different approach: using both formal and functional criteria, fine-grained analyses of just one grammatical feature from a single creole language were used to measure, not creoleness, but conformity to patterns observed in other world languages.

To conclude, then, I submit that an important contribution of this project was that it enabled systematic quantitative analysis of natural speech community data from an exhaustively transcribed corpus in order to test a methodology for typological research. In answer to repeated calls for interdisciplinary research, an innovative component of the study was its theoretically eclectic, empirically rigorous approach, which, it is hoped, will contribute to—and, indeed, marry—such seemingly disparate areas as variationist, typological, and creole studies (Bybee et al., Reference Bybee, Perkins and Pagliuca1994:32; Sankoff, Reference Sankoff1990:296, 310). Furthermore, this research aims to counter the stigmatization of Afro-Hispanic varieties by showing the systematicity of this creole language's preverbal particles, whose distributions adhere to crosslinguistic typological markedness patterns. Since the belief in language universals is not a necessary fact or a universally held opinion, the overarching goal of this experiment was to explore the viability of statements affirming the existence of a conceptual space that transcends cultural, linguistic, and ethnic boundaries, such as this one: “The categories defined by constructions in human languages may vary from one language to the next, but they are mapped onto a common conceptual space, which represents a common heritage, indeed the geography of the human mind” (Croft, Reference Croft2003:139). Indeed, then, given human cognition filtered through usage (what people talk about and how often), which is what actually propels grammaticalization, there is no reason for any language (or set of languages, such as creoles) to exhibit overall patterns that differ from one another.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I gratefully acknowledge the insightful comments from Joan Bybee and anonymous reviewers that greatly improved this paper.