Gender representation is a pervasive problem in political science. Evidence highlights uneven representation of—and credit extended to—women as experts generally (Beaulieu et al. Reference Beaulieu, Boydstun, Brown, Dionne, Gillespie, Klar, Krupnikov, Michelson, Searles and Wolbrecht2017), in publications (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017), in overall citations (Jensenius et al. Reference Jensenius, Htun, Samuels, Singer, Lawrence and Chwe2018; Dion, Sumner, and Mitchell Reference Dion, Lawrence Sumner and Mitchell2018; Maliniak, Powers, and Walter Reference Maliniak, Powers and Walter2013), in graduate training (Colgan Reference Colgan2016), and in tenure and promotion (Monroe et al. Reference Monroe, Ozyurt, Wrigley and Alexander2008), as well as networks (Atchison Reference Atchison2018) and bias in student evaluations (Mitchell and Martin Reference Mitchell and Martin2018), to name only a few cases. Concerns about gender representation also are increasingly common in conference participation. Although we see growing interest in addressing gender and other forms of inequality at conferences and workshops—with neologisms like “manels” (i.e., all-male panels) and “wominars” (i.e., all-female seminars) making their rounds through social media and among subdisciplinary communities—we as a discipline still lack a comprehensive understanding of the problem. This lack of understanding, in turn, inhibits our ability to seek effective solutions.

Focusing on how we construct conference programs is important because conference presentations are a critical part of a scholar’s professional development. First, for many political scientists, political science conferences such as meetings of the American Political Science Association (APSA), the Midwest Political Science Association, and others may be the first or only place a new working paper or research project is presented—especially for scholars from small departments or distant universities. Second, these large political science conferences are where many graduate students have their first opportunity to meet people in their field beyond their own PhD program, as well as to observe what is showcased as the “cutting edge” or “latest work” in their field. Third, conferences are where political scientists engage with—and potentially extend—established social networks, which are instrumental in career development and, unsurprisingly, an additional source of disadvantage to women (Gersick, Dutton, and Bartunek Reference Gersick, Dutton and Bartunek2000). Given that many colleges and universities cover travel expenses only for scholars whose name actually appears on a conference program, representativeness matters not only for presentations but also for ensuring that the wider pool of attendees is as inclusive as possible.

A conference program that is unrepresentative thus affects the discipline in at least three distinct ways: (1) it disproportionately inhibits the professional development of some members of our profession; (2) it misleadingly signals to the next generation “who does what kind of work”; and (3) it limits access to networking that, in turn, produces meaningful, career-building opportunities. For these reasons, we join a host of voices across the discipline in affirming that representation matters in professional conferences as in other aspects of the discipline.

A conference program that is unrepresentative thus affects the discipline in at least three distinct ways: (1) it disproportionately inhibits the professional development of some members of our profession; (2) it misleadingly signals to the next generation “who does what kind of work”; and (3) it limits access to networking that, in turn, produces meaningful, career-building opportunities.

This article draws on evidence from the 2017 and 2018 APSA Annual Meeting programs to discuss different forms of representation, identify where our annual conference achieves representation and where it falls short, and outline strategies for increasing representation. We use data provided by APSA on participants’ self-reported gender identity and investigate the correspondence between gender composition in each section and across divisions in the conference program. We show that sections differ substantially in their gender representation: although some are representative of their membership, others are not, and some sections are particularly likely to feature manels. We present representation data by organized section, discussing what representation looks like (e.g., Does a female chair or discussant “break” a manel?) and engaging a debate over what representation goals should be (e.g., Measured as a percentage of section membership, given structural barriers that might undersubscribe women to a section?).

Finally, we draw on our own experience as program cochairs for the Comparative Politics division and feedback from other division chairs that we collected systematically through correspondence to outline challenges for achieving representation. A key lesson from our collective experience is that program organizers frequently want to prioritize diversity and representativeness but rarely communicate that to submitters—or have not found effective ways for doing so. We conclude by offering guidelines to increase gender representation for potential submitters and program chairs.

Although we tailored our discussion to target gender representation among conference and workshop organizers, it should be of interest more broadly to the political science discipline and to different categories of underrepresented and marginalized scholars. In particular, our discussion of the three goals of representativeness, equality, and diversity also may be applied to race, ethnicity, institutional affiliation, or any other characteristic that differentiates political scientists from one another. We chose to focus on gender as a first step because current debates on gender in academia highlight this as a central issue for political scientists and because of the availability of data. However, we welcome further research on other dimensions of diversity at political science conferences, as well as the challenges and opportunities of intersectional representation. In what follows, we periodically address other forms of identity to highlight areas in which future research may build on this work.

IS INCLUSION ENOUGH?

Few would probably disagree that participation at the APSA Annual Meeting should reflect the population of people who study political science. However, there are many different ways in which this might be achieved, including different types of objectives for program organizers: participation, representation, equality, and diversity. Female participation at APSA Annual Meetings has increased steadily in past decades (Gruberg Reference Gruberg1993; Reference Gruberg2006; Reference Gruberg2009). This is reassuring, but participation (or attendance) is different from representation, which necessitates visibility in the program.

A representative conference program matches the reference population of political scientists. In the case of gender representativeness, APSA’s total membership is about 37% female (according to the APSA website in early December 2018); therefore, the conference program would be representative if 37% of participants were women. However, this metric is immediately challenged by whether the conference program as a whole is the appropriate unit of analysis for gauging representativeness.Footnote 1

A second alternative to within-conference representation is to look for representativeness within divisions: that is, matching the proportion of women in each division’s allotment of panels with the proportion of women in each organized section. A third alternative is to achieve representativeness by section within panels. Each objective has different implications for program organizers; as the unit of analysis shrinks, the challenges of representativeness increase.

Our use of representation is consistent with what Pitkin (Reference Pitkin1967) termed descriptive representation, in which individuals are representative of their reference population if they share the same descriptive characteristics (in this case, the same gender). There are alternative ways of conceptualizing representation; descriptive representation most often is contrasted with substantive representation, in which representatives reflect the interests of their reference population (see Wängnerud Reference Wängnerud2009 for a review of descriptive versus substantive representation in legislatures). Acknowledging the importance of this distinction, we take no position on how to obtain substantive representation in the construction of conference programs or workshops. Focusing on manels, gender balance, and characteristics of conference or workshop participants reflects a concern among political scientists about descriptive representation, and it is this concern that this article addresses.

Equality is a separate objective: that is, balancing participation across group characteristics, such as equal numbers of women and men. Program organizers may prioritize the participation of particular groups even if they do not match the “supply.” For example, a section in which women comprise a relatively small proportion of its total membership may choose to increase the proportion of women in its program. This also may operate at different scales: equality within sections or within panels. Distinct from the objectives of equality and representativeness is an objective that we term diversity, which we reserve specifically to mean an objective that is neither equality nor representativeness but rather the avoidance of uniformity. The distinction between equality and diversity is important: for example, a panel with six participants, only one of whom is a woman, is diverse but not equal according to gender. When conference organizers consider the issue of manels, they are focusing on gender diversity even if they are not achieving gender equality.

For large disciplinary organizations such as APSA, achieving representativeness at the level of the entire conference is a minimal objective. Given that APSA’s membership sorts into organized sections according to interests, and recognizing that membership profiles differ substantially across sections, organizers also may seek to achieve representativeness within sections. Sections that are particularly unbalanced in terms of gender, race, or other characteristics may place greater weight on equality than on representativeness in an attempt to nurture greater balance, especially if they are smaller in membership and panel allotment. At the same time, however, research presentations happen in panels, and this is the formal locus of social interaction for most conference attendees. Recent discussions of manels reflect the common belief that diversity—if not necessarily representativeness—is a central objective within the space in which social interaction actually happens.

Recent discussions of manels reflect the common belief that diversity—if not necessarily representativeness—is a central objective within the space in which social interaction actually happens.

ARE WE REPRESENTATIVE? ARE WE DIVERSE? EVIDENCE FROM THE APSA PROGRAM

We drew on the 2017 and 2018 APSA Annual Meeting programs to see how recent conferences are faring in terms of these objectives. For this analysis, we focused exclusively on gender.Footnote 2 We obtained data from APSA on all formal events at the 2017 and 2018 Annual Meetings, including (anonymized) data on each participant in each panel, roundtable, and special event.Footnote 3 We aggregated the data by division and matched these data with additional APSA data on the gender breakdowns by organized sections.Footnote 4 This match was imperfect because not all APSA program divisions correspond to APSA organized sections—for example, there is no Formal Political Theory organized section or a Comparative Politics of the Advanced Industrial Democracies section. In what follows, therefore, we present only representativeness data for those divisions that we could match with organized sections.

Figure 1 plots the percentage of each section that is female against the percentage of each division’s female participants. The right-hand plot counts all panel participants; the left-hand plot counts only presenters and authors, thereby excluding chairs and discussants (see following discussions of these two panel roles). Sections with higher female-membership rates appear at the top of the figure. The vertical reference line corresponds to the 37% female APSA membership.

Figure 1 Representativeness by Division

Figure 1 shows that sections vary in representativeness. Political Methodology is the most gender-unequal section in terms of membership, but its conference program is representative of section membership. Other sections may surpass the 37% threshold but still underrepresent section membership on panels (e.g., Human Rights).

Patterns of underrepresentation are not new; in fact, parts have remained unaltered for decades. Writing of women’s participation in the 1992 APSA Annual Meeting program, Gruberg (Reference Gruberg1993) observed that “the sections with the strongest female representation were those on Law and Courts; Public Administration; Public Policy; Women and Politics; Race, Gender, and Ethnicity; History and Politics; and Politics and Life Sciences,” whereas among the weakest representation were “Formal Political Theory; Political Methodology; Presidential Research; Comparative Politics; Politics of Developing Areas; International Collaboration; International Security and Conflict; and Religion and Politics.” By the 2008 APSA Annual Meeting, repeat offenders included Formal Political Theory, Political Methodology, and International Security and Arms Control, as well as Comparative Politics of Advanced Industrial Societies, Conflict Processes, Legislative Studies, Public Opinion and Political Participation, and International History and Politics (Gruberg Reference Gruberg2009). Moreover, writing a decade later, almost 30 years after the original study, we see that many such patterns persist—however, the Comparative Politics division program is now representative of the Comparative Politics section and of APSA’s broader membership.

We also recognize a difference between integrated and siloed representation. As Breuning and Lu (Reference Breuning and Lu2010, 247) noted in their study of the International Studies Association (ISA),“[i]t is important to understand not just how many women participate…” but also “where they are located and whether, and to what degree, their scholarship intersects with that of the men participating in the meeting.” As the data suggest, panels that overrepresent women on the program (e.g., Women and Politics) may be large but siloed from sections that exhibit underrepresentation. This siloing effect at APSA also is not new. Gruberg wrote in his 1992 evaluation of APSA participation that the highest representation of women occurred in panels on gender studies, even when excluding panels in the Women and Politics section. The opposite effect—“lopsidedly stag panels”—includes a long and varied list across the discipline’s subfields.

This pattern also is visible in sister associations. In a study of participation in the Canadian Political Science Association’s annual conference, Tolley (Reference Tolley2017) observed a strong siloing effect in which gender-related research is “often presented in gender-focused panels and not incorporated across the discipline’s subfields.” Meanwhile, in a comprehensive multiyear study of ISA participation (a majority of whose membership consists of political scientists), Breuning and Lu (Reference Breuning and Lu2010, 252) found that women not only over-participate as a percentage of membership but also that “participations are unevenly distributed across the various organized sections.”

Looking beyond descriptive patterns of representation, a second question that emerges from the data is whether smaller sections are less representative because they are constrained by a smaller number of panels. If this is generally true, then larger sections should be more representative than smaller sections: that is, a positive correlation between the number of panels in a section and its gender representativeness. We created a measure of representativeness by calculating the ratio of female participation in a division to female membership in a section, where values greater (less) than one indicated that women are over- (under-)represented in the program relative to the section. Figure 2 compares representativeness and division size as measured by the number of panels, highlighting those divisions whose representativeness value is less than 0.8.

We found that, on average, smaller sections actually tend to be more representative than larger sections. Section size alone does not explain why some sections are less representative than others.

Figure 2 Division Size and Representativeness

We found that, on average, smaller sections actually tend to be more representative than larger sections. Section size alone does not explain why some sections are less representative than others.

We also can measure diversity within panels across sections. To do so, we coded whether each panel at each APSA Annual Meeting is a manel (i.e., every participant is male). We excluded the role of chair from evaluating composition, recognizing this role to be procedural and non-substantive. We acknowledged, however, that there can be a difference of opinion about whether or not inviting a woman to serve as discussant achieves diversity. Is a discussant a role that confers prestige or an onerous task that prevents scholars from presenting their own independent research? The answer to this question likely varies by conference and by discipline as well—in some venues and for some disciplines. Thus, we present two measures of manels: one with discussants and chairs (“all participants”) and one without (“authors and presenters”). Finally, we note that APSA participation rules also make it possible that a panel comprised of papers with diverse coauthor teams nevertheless features only male presenters because female coauthors register as “nonpresenting coauthors.”

Figure 3 compares the number of panels in each division with the percentage of those panels that are manels, labeling each division or related group with more than two panels and whose “manel rate” is greater than 20%. We calculated manel rates for every division and related group at APSA.

Figure 3 Manels by Division or Related Group

The figure shows that some divisions and related groups, including some especially large ones, are particularly likely to feature manels and that there is consistency across years (i.e., American Political Thought, Canadian Politics, the Claremont Institute, Eric Vogelin Society, Formal Political Theory, and Political Methodology). We noted also that there are many related groups allocated only one panel, which is a manel, although we did not label them here.

As a final exercise, we investigated the relationship between the gender of the division organizer and panel diversity. Specifically, we combined the previous data on manel rates by division with data on division program (co)chairs and determined whether divisions with one or more female program chairs were more likely to avoid manels.Footnote 5 In addition to testing this bivariate relationship, we also controlled for the total number of panels per division, as well as the gender diversity of the corresponding organized section (where available). The results are in table 1.

Table 1 Predicting Manels

Notes: OLS regressions with robust t statistics in parentheses. *p<0.1, **p<0.05. The dependent variable is the percentage of panels in each division that are manels. Data are from the 2017 APSA Annual Meeting.

Models 1–4 show that having a female chair or cochair predicts about 8% fewer manels when we adopted our narrower definition of manels, which only checks authors and presenters. This result held even when we controlled for the number of panels in the division and the gender composition of the corresponding section. Model 4 drops two sections—Women and Politics Research and Sexuality and Politics—and the results remain substantively identical.Footnote 6

Models 5–8 repeat models 1–4 but for all participants rather than only authors and presenters. The previously mentioned correlation between program (co)chair gender and manel rates did not survive. We interpreted this as suggesting that female program chairs are attuned to substantive and meaningful participation in panels (i.e., authors and presenters) and paying less attention to chairs and discussants.

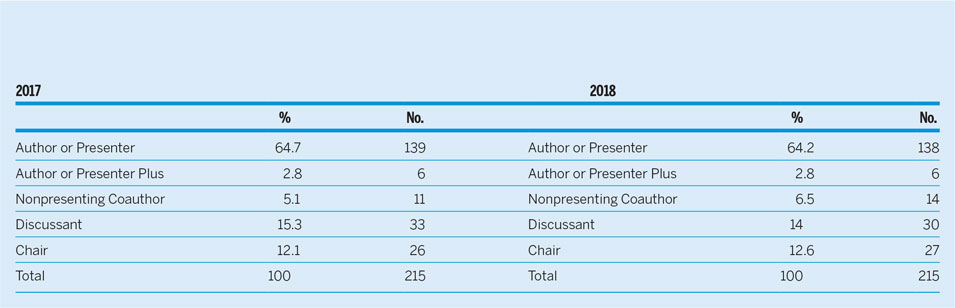

We also can examine which roles women play in panels that have only a single woman. To do so, we classified participants in one of five roles: nonpresenting coauthor (i.e., on the program but not presenting in the panel); author or presenter; author or presenter “plus” (i.e., also serving as discussant or chair); discussant; and chair (see table 2).

Table 2 Women’s Participation in Single-Woman Panels

We found that among these panels in which a single woman’s participation prevents it from being a manel, around two thirds of participants were presenting their own research. The remaining third were women who performed service roles or did not actually present their own research. Further analysis (available on request) did not reveal any clear patterns across divisions in what types of roles women are playing in these single-woman panels. We noted that in 2017, women were 43% of all chairs, 40% of all discussants, and 41% of all authors and presenters; in 2018, those figures changed slightly to 46% of all chairs, 41% of all discussants, and 40% of all authors.Footnote 7 These percentages compare favorably to the roughly 37% of APSA’s membership who are women.

Figure 4 examines whether there are differences in rates of participation by gender, counting the number of distinct panels (rather than roles) in which each attendee appears on the program. The comparison between frequency of participation for men and women is instructive.

Figure 4 Participation by Gender

Many more men than women appear only once on the program. However, looking at those participants who appear twice or even more frequently, there are smaller differences between men and women in both years.

The preceding discussion entertains three explanations for differences in gender diversity and representation across APSA divisions: section membership, division size (in terms of panel allocation), and gender of the division (co)chair. There obviously are other factors that explain differences across sections. One possibility is that certain sections have earned a reputation for being unfriendly or unwelcoming to women. Another is that subdisciplinary “cliques” that happen to be unrepresentative of a section’s broader membership have captured the leadership of a particular section. Still another is that particular sections or divisions have members who are not interested in achieving diversity. Each factor would imply patterns of inequality or lack of diversity that persist across multiple years. Our quantitative approach is not well suited to identifying the specific causal factors that might explain individual section or division performance. Still, we suspect that these factors explain why some divisions are consistently less representative and less diverse than others.

However, across APSA divisions, manels are less common in more gender-balanced sections and when there is a female program (co)chair.

A VIEW FROM THE PROGRAM SIDE

The data reviewed here show that as a discipline, we still have a long way to go. Our experience as Comparative Politics program organizers—the largest section at the 2017 APSA Annual Meeting with the largest panel allocation (i.e., 56 panels)—invites us to reflect on and offer a series of heuristics for how organizers may increase representation at different units of analysis. For program chairs, we suggest three deliberate steps: (1) prioritization a priori, (2) promotion, and (3) assembly awareness, as follows:

1. Prioritization invites program chairs and conference organizers to identify inclusion objectives prior to the call for submission. In other words, goals should not emerge organically once proposals have been received but rather should be announced before the call is distributed.

2. Promotion requires not only circulating the call itself but also clearly communicating the goals of inclusion and expectations of proposed panel composition. This may be in explicit messaging that manels would not be accepted. Goals also can be communicated by expanding the networks in which the call is circulated.

3. Programs and panels can be assembled with awareness to representation needs. Organizers may strive for diversity within each panel or panel diversity within each section. In other words, achieving diversity within each panel may be difficult, particularly for sections with few panel allocations. Organizers also may choose to prioritize certain panels to be representative, such as high-attendance panels and panels featuring senior scholars.

The supplemental online appendix discusses these perspectives in greater depth and also proposes institutional best practices that might foster the long-term goal of inclusion across future meetings.

CONCLUSION AND MOVING FORWARD

This analysis offers a panoramic overview of representativeness, equality, and diversity at APSA Annual Meetings, across both divisions and panels within divisions. First, some divisions with lopsided gender ratios are nevertheless fairly representative of the organized sections that represent their key constituencies. Second, there is variation across years in how representative APSA divisions are; individual organized sections may want to take note of those sections and years that are particularly unrepresentative. Third, we uncovered some correlates of manels: they are common among APSA related groups that have only one panel allocated to them. However, across APSA divisions, manels are less common in more gender-balanced sections and when there is a female program (co)chair. We found no evidence that smaller divisions tend to be less representative; neither did we find that smaller divisions or organized sections have more manels.

We can do better as a discipline, and we believe that it is our collective responsibility to strive for greater inclusivity in our annual meeting.Footnote 8 One possibility is to implement a “no manels” rule, as some British universities and the Political Studies Association have done. However, we recommend instead that the community of APSA members collectively encourage conference and program organizers to do the actual work and to be deliberate in achieving representation rather than implementing a hard-and-fast rule.

Building on the role of the APSA community in fostering a diverse and representative annual meeting, we conclude with recommendations on how “submitters” and the disciplinary community more broadly can help conference organizers to achieve representation goals. When submitting panel proposals, panel organizers should look outside of their “disciplinary hierarchy” (Lake Reference Lake2016) and think deliberately about panel construction and prioritize invitations to women and underrepresented minorities as paper presenters first before extending invitations for discussant and chair. This should ensure that underrepresented communities have a greater substantive role at APSA Annual Meetings. It also is easier than ever to reach out to new communities and identify new scholars, with efforts by Women Also Know Stuff and People of Color Also Know Stuff to organize scholars by expertise. It also helps to volunteer to be a discussant or chair (APSA allows scholars to sign up when they submit a proposal) and to be searchable online. These small steps taken by APSA members can go a long way in ensuring that our annual meeting is both diverse and representative of our community.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519000908