Hypertrophic olivary degeneration (HOD) occurs secondary to a lesion in the dentato-rubro-olivary pathway (DROP), such as hemorrhage or a tumor.Reference Gu, Carr, Kaufmann, Kotsenas, Hunt and Wood 1 , Reference Konno, Broderick, Tacik, Caviness and Wszolek 2 Listerial rhombencephalitis is a rare etiology of HOD.Reference Gu, Carr, Kaufmann, Kotsenas, Hunt and Wood 1 – Reference Chhetri, Dayanandan, Bindman, Mathur and Mills 4 We report the case of a patient with delayed-onset HOD following listerial rhombencephalitis.

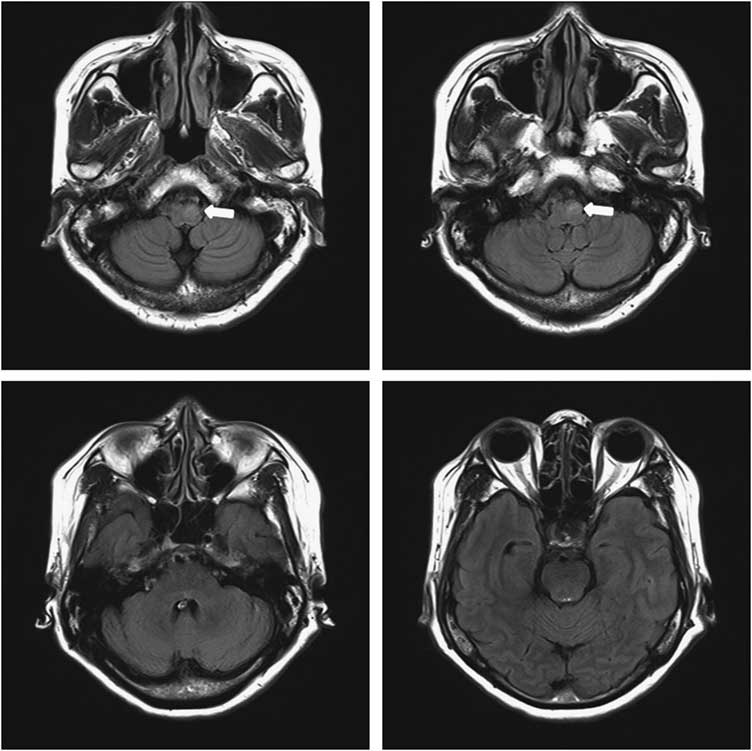

A 48-year-old woman visited the emergency room with a 4-day history of fever and diminished consciousness manifesting as mild drowsiness, ptosis of the left eyelid, and complete bilateral ophthalmoplegia. MRI of the brain showed hyperintense lesions on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences extending from the midbrain to the lower brain stem (Figure 1). The CSF pressure was elevated (305 mm H2O; normal 70-180 mm H2O), with increased leukocytes (365/mm3: 30% neutrophils, 70% lymphocytes) and protein 122.0 mg/dL, and slightly low glucose 44 mg/dL (serum glucose level was 172 mg/dL). The patient’s adenosine deaminase level was increased to 12.9 U/L, which was highly suspicious for tuberculous meningitis. Anti-tuberculosis therapy was started empirically with isoniazid (300 mg/day), rifampicin (600 mg/day), pyrazinamide (1500 mg/day), and ethambutol (1000 mg/day). In all, 2 days after admission, respiratory failure occurred, and intubation was performed. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and was maintained on the existing therapy.

Figure 1 MRI of the brain at the first admission. Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequence shows hyperintense lesions extending from the midbrain to the lower brain stem.

Listeria monocytogenes was confirmed by CSF culture on day 7, and ampicillin (12 g/day) and gentamicin (260 mg/day) were administered under the diagnosis of rhombencephalitis due to L. monocytogenes. After 12 days, the slight hearing loss was suspected, and the gentamicin was discontinued, although the ampicillin was continued for a total of 4 weeks.

The patient was discharged after completion of the treatment, at which time the ophthalmoplegia and diplopia were mostly resolved except for lateral gaze palsy, ptosis of the left eyelid, and dysarthria.

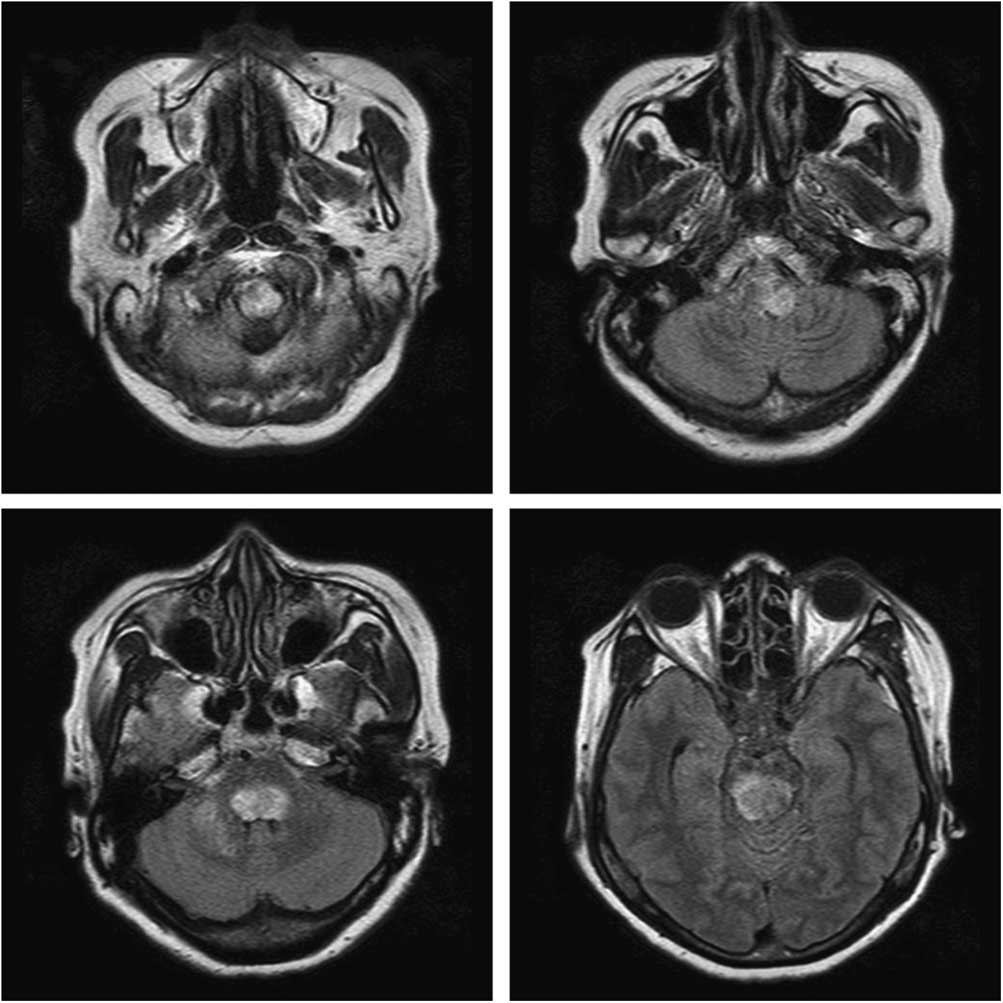

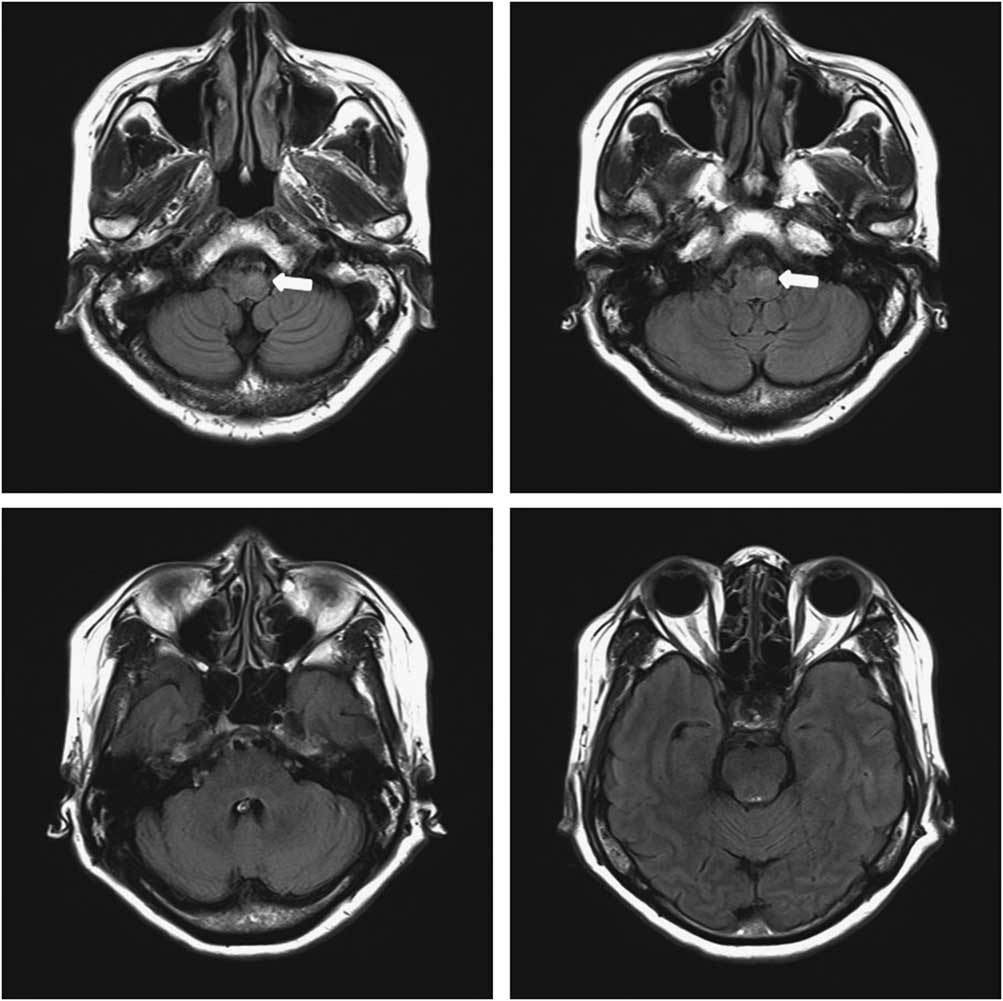

In all, 4 months after discharge, she complained of a foreign body sensation in her neck, accompanied by an altered, harsh voice. She underwent laryngoscopic examination, which indicated possible gastroesophageal reflux disease, and was treated with a proton pump inhibitor. The symptoms persisted for 2 months, however, and tremor of the soft palate was observed. A second laryngoscopic examination revealed the oscillating movement of the left vocal cord. Her follow-up MRI scans exhibited an increased signal in the left inferior olive (Figure 2). She was then diagnosed as having HOD secondary to rhombencephalitis. It was treated unsuccessfully with clonazepam and baclofen.

Figure 2 Follow-up brain MRI 6 months after treatment. Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image demonstrated hyperintensity with enlargement of the left inferior olive (arrow) and disappeared state of the previous lesion on the pons and midbrain.

Listerial infection occurs mostly in immunocompromised hosts, being uncommon in the general population.Reference Carrillo-Esper, Carrillo-Cordova, Espinoza de los Monteros-Estrada, Rosales-Gutierrez, Uribe and Mendez-Sanchez 5 – Reference Jubelt, Mihai, Li and Veerapaneni 7 Clinically, it appears most frequently as acute bacterial meningitis, less commonly as meningoencephalitis, and least commonly as septicemia or gastroencephalitis. But, unlike classical listerial infection in the central nervous system, listerial rhombencephalitis often occur in immunocompetent patients.Reference Carrillo-Esper, Carrillo-Cordova, Espinoza de los Monteros-Estrada, Rosales-Gutierrez, Uribe and Mendez-Sanchez 5 – Reference Jubelt, Mihai, Li and Veerapaneni 7 In the process of listerial rhombencephalitis, it has been proposed that invasion of L. monocytogenes via neural retrograde transport along the cranial nerves, rather than invasion from the bloodstream, is the most likely to occur.Reference Disson and Lecuit 6 Neurologic sequelae in affected patients are common, even when the patient survives. L. monocytogenes infection should be evaluated as a treatable etiology of rhombencephalitis, as in cases of enterovirus infection, herpes simplex virus infection, multiple sclerosis, and Behçet’s disease.Reference Jubelt, Mihai, Li and Veerapaneni 7 , Reference Moragas, Martinez-Yelamos, Majos, Fernandez-Viladrich, Rubio and Arbizu 8 Arriving at a proper diagnosis of rhombencephalitis is essential but challenging because the clinical symptoms and laboratory findings are atypical for a bacterial infection.Reference Carrillo-Esper, Carrillo-Cordova, Espinoza de los Monteros-Estrada, Rosales-Gutierrez, Uribe and Mendez-Sanchez 5 , Reference Jubelt, Mihai, Li and Veerapaneni 7 , Reference Moragas, Martinez-Yelamos, Majos, Fernandez-Viladrich, Rubio and Arbizu 8

Hypertrophic olivary degeneration is a form of trans-synaptic degeneration caused by disruption of the DROP, also known as the Guillain–Mollaret triangle (GMT), connecting the ipsilateral inferior olivary nucleus, the dentate nucleus of the contralateral cerebellum, and the ipsilateral red nucleus.Reference Gu, Carr, Kaufmann, Kotsenas, Hunt and Wood 1 – Reference Blanco Ulla, Lopez Carballeira and Pumar Cebreiro 3

The epidemiology and etiology of HOD are not fully understood. The most common causes of injury to the GMT are intraparenchymal hemorrhage, arteriovenous malformation, an infarcted tumor, surgery, and multiple sclerosis,Reference Gu, Carr, Kaufmann, Kotsenas, Hunt and Wood 1 – Reference Blanco Ulla, Lopez Carballeira and Pumar Cebreiro 3 but HOD following listerial rhombencephalitis is very rarely reported.Reference Chhetri, Dayanandan, Bindman, Mathur and Mills 4

The proposed mechanism of HOD is that is an atypical form of trans-synaptic degeneration thought to be due to the loss of synaptic, afferent input to the inferior olivary nucleus, resulting in hypertrophy, initially of the affected neurons, followed by subsequent atrophy. Typical MRI findings include initial hypertrophy and T2 hyperintensity evolving over time to atrophy with residual hyperintensity on T2-weighted images. A lesion on the afferent dentato-rubro-olivary fibers result in unilateral or bilateral HOD, depending on its location along the pathway.Reference Gu, Carr, Kaufmann, Kotsenas, Hunt and Wood 1 – Reference Blanco Ulla, Lopez Carballeira and Pumar Cebreiro 3 In the case reported here, however, accurate identification of the primary focus of HOD was difficult because lesions appeared throughout the brain stem.

Disruption of the GMT results in a varied clinical presentation, including palatal tremor, dentatorubral tremor (Holmes tremor), and ocular myoclonus.Reference Gu, Carr, Kaufmann, Kotsenas, Hunt and Wood 1 – Reference Chhetri, Dayanandan, Bindman, Mathur and Mills 4 Although this patient underwent an otolaryngologic examination for globus pharyngeus and an altered voice, it was difficult to diagnose HOD. Delayed neuronal degeneration, such as HOD, may be diagnosed in patients who have been treated for rhombencephalitis that displays only vague symptoms, such as the sensation of a foreign body in the neck.

In conclusion, rhombencephalitis due to listerial infection has been very rarely reported as a cause of HOD. Based on our report, HOD should be considered in the differential diagnosis of rhombencephalitis patients with late-onset neurological sequelae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the 2018 Inje University research grant. There is no conflicts of interest in this study.