The Reich Banking Law (Reichsgesetz über das Kreditwesen) was the first comprehensive legislation over the entire German banking sector. Its implementation in 1934 arose from extensive deliberations among officials—including those at the central bank (Reichsbank); the cabinet; and the finance, economics, interior, and justice ministries—to address the vulnerabilities of the financial sector. The legislation further marked a pivotal moment in the formation of a regulatory policy that standardized rules and established new supervisory functions. As this article argues, neither the 1931 banking crisis nor the 1933 Nazi seizure of power alone can fully explain the enactment of banking regulation, as one must also consider the longer-term structural factors that induced such a change. Above all, the Reich Banking Law was a reactionary political decision that was intended to protect the national economy from foreign withdrawals of capital and exchange-rate volatility. By identifying the Reich Banking Law as one of many possible configurations of intervention that could have arisen, the following analysis probes the relationship between the state and the economy.

Officials in prewar and interwar Germany had been greatly distressed by the vulnerability of the national financial sector. Specifically, they questioned whether banks were reporting adequate levels of liquidity—the volume of cash and cash equivalents (government securities, bills of exchange, or advances), often in proportion to bank deposits—on their balance sheets.Footnote 1 Here, liquidity can be interpreted as a measure of how resilient a particular bank might have been to a crisis of confidence or a bank run. Moreover, contemporary assessments connected this issue to other problems, such as the deficient supply of industrial credit or the heavy reliance on foreign sources of capital. As Reichsbank director Karl Nordhoff observed, the “liquidity question” (Liquiditätsfrage) undermined the stability of the entire German economy: “Insufficient liquidity causes not only distrust on the part of the bank's customers, [but] there is also the danger that such expressions of distrust . . . will spill over to other banks. For this reason, there can be no doubt that not only the banks themselves, but also the government authorities generally responsible for credit and monetary affairs and the central bank, as well as public criticism, must pay the greatest attention to questions of the liquidity of banks.”Footnote 2 Nordhoff's call for greater financial oversight in 1933 derived from the persistent fear of inadequate liquidity in the years prior. Not only were banks reporting low levels of cash reserves, but their balance sheets also revealed a significant dependence on foreign capital. Officials thus came to believe that the liquidity question was both a structural problem endemic to the banking sector and an outgrowth of global entanglements. From this perspective, protecting the economy from foreign volatility became a matter of national security.

As others have argued, the incentives for a state to enact banking legislation have varied widely, ranging from efforts to exert control over the economy to an interest in improving overall market efficiency.Footnote 3 Banking regulation, indeed, proved more difficult than simply imposing a standard set of rules on the entire financial sector. It was a deeply politicized project, subject to numerous debates on state involvement and public law. In the German case, officials considered the extent to which a supervisory authority needed to be independent from the government itself.Footnote 4 They were interested in identifying an enforcement mechanism for such legislation, as well as the necessary legal arguments for their actions.Footnote 5 At the same time, there was tension between these views and those that remained committed to classical-liberal principles of a limited state. From industrialists on government commissions to prominent bankers in Berlin, many groups advocated a model of indirect supervision over the banking system.

This article identifies the rationale that underpinned the state's regulatory policy. It argues that banking regulation was a product of protracted discussions over government intervention since the turn of the century. In contrast, historians have argued that the Reich Banking Law was a predominantly technocratic policy independent of the state, a direct outcome of the 1931 banking crisis, or the result of Nazi economic policy.Footnote 6 Some of these arguments were made by contemporary observers, too.Footnote 7 Meanwhile, Christoph Müller has shown how formal banking legislation arose from the economic problems facing Germany after World War I.Footnote 8 However, although such factors had contributed to overall banking instability, attempts to increase financial oversight more directly came from extensive debates in both the prewar and interwar years. First, prior to 1914, the government sought to protect the German financial sector from foreign crises. Banking regulation had certainly embodied the evolving legal paradigms of “liquidity” and “solvency” from the mid-nineteenth century onward.Footnote 9 Nevertheless, while there is no singular origin of an analysis of the liquidity question, the proceedings of the 1908 Bank Inquiry (Bankenquete) serve as one useful starting point since it was within recent institutional memory.Footnote 10 Second, in the 1920s, economists, lawyers, and bankers blamed the international situation—the burden of reparations, the dependence on foreign capital, and the gold-hoarding policies of other countries—as the primary reasons for low liquidity. They often resorted to indirect means of financial supervision, such as credit limits or alterations to the discount rate, which allowed the government to manage market instability without formal legislation. It was in this context that the foundation of a more interventionist regulatory policy emerged.

This argument also requires understanding the transnational elements of political debates, which determined the possible configurations of a regulatory policy. From the early 1900s onward, German officials noted the differences between their banking system and the British one. Because of the relatively weaker positions of their own banks, they became more committed to sweeping (albeit different) forms of regulation than their British counterparts, the latter often finding ways of regulating the banking sector through private meetings and informal pressure.Footnote 11 Moreover, comparisons with foreign banking systems serve a second purpose here: German officials observed how Germany had become exposed to economic and political vicissitudes abroad. There was criticism of other countries for causing volatility and, by extension, threatening national security. After the Panic of 1907, Reichsbank director Karl von Lumm claimed that a “stronger foreign-exchange portfolio” was a “valuable weapon” for the central bank in preventing future withdrawals of capital.Footnote 12 Similarly, with an influx of short-term foreign capital after 1924, officials believed they now had less control over domestic credit and price levels.Footnote 13 “Deflation is not dependent on our will but simply an inevitable consequence of international conditions,” stated Reichsbank president Hans Luther. “The liquidity question is the main issue.”Footnote 14

Even so, resolving the debate on the crisis that beset Germany in the summer of 1931 is not the goal here.Footnote 15 Recent scholarship has detailed how a “sudden stop” in foreign capital flows exacerbated the current-account deficits of Germany, Austria, and Hungary.Footnote 16 The crisis in central Europe posed a major problem for the British merchant banks that had significant continental holdings of acceptance credits.Footnote 17 Institutionalized efforts to resolve the liquidity shortage first emerged through financial-sector initiatives—the Acceptance and Guarantee Bank (Akzept- und Garantiebank, 1931), the German Financing Institute (Deutsche Finanzierungsinstitut, 1932), and the Amortization Fund for Commercial Loans (Tilgungskasse für gewerbliche Kredite, 1932)—and were later embodied by the 1934 Reich Banking Law. While efforts to expand the state apparatus in financial affairs certainly accelerated after the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the process had, in many ways, already been underway.

The Making of the Liquidity Question

Although prewar Germany did not implement nationwide banking regulation, it was responsible for an evolution in the political economy of financial-sector intervention. Initially, the monetary authorities grappled with the question of whether banks were reporting adequate levels of liquidity.Footnote 18 Germany's banking sector broadly comprised three main groups: private banks, including mortgage banks (Hypothekenbanken), provincial banks (Provinzbanken), and the Berlin-based “Great Banks” (Großbanken); public banks, such as state banks (Staatsbanken), regional banks (Landesbanken), and savings banks (Sparkassen); and cooperative banks (Genossenschaftsbanken), which supported farmers and other small to medium-sized businesses. Across these groups, published balance sheets revealed a decline in the cash-liquidity ratios since the early twentieth century (Table 1).

Table 1 Cash-Liquidity Ratios by Bank Type (as Percentages of Total Deposits)

Source: Compiled by the 1933–4 Committee of Inquiry in: “Liquide Mittel und Liquiditätsquoten” [Cash and cash equivalents and liquidity ratios], in Untersuchung des Bankwesens 1933, part 2 (Berlin, 1934), 88–97. Note: These figures include branches and are based on published balance sheets at year's end (except for 1933, which is based on the October balance sheet).

It was the multiplicity of institutions that complicated the task of implementing comprehensive regulation, hitherto confined to other areas of the financial system. Since the nineteenth century, the rapid growth of the banking sector depended on several factors: the state's demands for loans to fund wars, as well as new social programs; private-sector industrialization via railroads and other technologies; and the proliferation of overseas opportunities for investment.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, the German states maintained only a limited role in financial oversight. For instance, in 1838, Prussian savings banks were subject to some reporting requirements, but self-regulation was commonplace in their daily operations.Footnote 20 Subsequent governments enacted more reforms, such as the establishment of the Prussian State Bank (a private corporation under state ownership) in 1846. Yet even after unification in 1871, Germany did not impose nationwide regulation over the banking sector, in contrast to other areas of reform, including health insurance, pensions, and cooperative law.Footnote 21 This absence cannot be explained by a lack of awareness. Other countries, notably England and Sweden, had introduced legislative changes in the 1840s for new banking codes that outlined charter requirements and minimum capital ratios for private banks to operate.Footnote 22 Nor did the state struggle with an institutional incapacity to enact widespread regulation. While chambers of commerce and other private organizations had regulated the commodity and stock exchanges, most prominently in the agriculture sector, an imperial act in 1896 brought their supervision under state control.Footnote 23

There were, however, discussions on the idea of banking regulation at the turn of the century in response to financial instability abroad. In the United States, a collapse in public confidence led to a run on trust companies in 1907. Facing a liquidity crisis of their own, New York banks then decided to impose restrictions on withdrawals of bank deposits, prompting a rise in interest rates and a net inflow of gold to the United States of $85 million by year's end.Footnote 24 These developments, followed by a bailout from J.P. Morgan, instigated an examination into the crisis by the members of the National Monetary Commission, whose recommendations formed the basis of the Federal Reserve in 1913. Yet the Panic of 1907 had also been a transatlantic crisis, one wrought by the global interconnectedness of prewar money markets.Footnote 25 Subsequent capital outflows from Germany, as investors searched for higher interest rates abroad, forced the Reichsbank to raise its discount rate from 5.5 percent to 6.5 percent in October and 7.5 percent in November. Following the drain in gold, Reichsbank president Rudolf Havenstein announced to the German Parliament (Reichstag) his intention to oversee a public inquiry into the banking system.Footnote 26 He planned to investigate whether the banks were holding an adequate volume of “minimum reserves” across their nationwide branches, as well as the extent of the Reichsbank's responsibilities in setting the discount rate.Footnote 27

In the summer of 1908, the proceedings of the Bank Inquiry commenced with an opening statement by Havenstein that affirmed his interest in procuring advice from “this body of experts.”Footnote 28 The deliberations among economists, bankers, lawyers, and civil servants focused on, among many concerns, how to insulate the financial system from panic-induced outflows. Adolph Wagner, an economist whose 1901 proposal for a regulatory office had garnered little support, reiterated his belief that organized intervention was needed to alleviate “the ups and downs of economic life.”Footnote 29 Yet the general view of the commission was against sweeping reform. According to one industrialist, “we hear nothing but a clamor for state supervision and the creation of new officials in order to supervise where there is no need for supervision.” Alternative means for protecting the country's reserves, such as removing the tax on metallic imports, might have afforded temporary relief to the strains imposed by foreign crises.Footnote 30 Practicality was also important since, outside the commission, a professor from the University of Breslau claimed it would have taken “a large army of civil servants” to audit the Great Banks.Footnote 31

Although no immediate legislative changes were made to the financial system, notwithstanding a revision of the Reichsbank's own statutes in 1909, the Bank Inquiry had several important implications in expanding the role of the state in financial affairs.Footnote 32 Both the Reichsbank and interior ministry were concerned with the question of whether banks were holding an adequate volume of liquidity. Ensuring financial stability might have been possible, as Interior Minister Clemens von Delbrück hinted, if the state could have promoted transparency through the publication of their balance sheets.Footnote 33 Such projects of collecting economic statistics and preparing data for publication had long served an important purpose for the state.Footnote 34 From March 1909 onward, the largest banks agreed to share their financial statements on a bimonthly basis.Footnote 35 Indeed, statistics were vital for assessing conditions in the banking sector. As Nordhoff later argued, improving the quality of statistics helped officials make better “conclusions for the policy of the [central] bank.”Footnote 36

When in April 1911 the Agadir crisis in Morocco caused a run on German banks, officials again prioritized state intervention. The Reichsbank made bimonthly reporting a legal requirement and, two years later, organized a cartel under the auspices of the Stamp Association to stabilize interest rates among banks.Footnote 37 By June 1914, Havenstein, with support from Anton Arnold, the new head of the Reichsbank's statistical division, proposed a reform to raise liquidity by requiring banks to increase their own cash reserves among local associations or their accounts directly held by the central bank.Footnote 38 The goal was to “limit ourselves to minimal proposals that will not impose an excessive burden on any bank, that can be implemented without seriously disrupting economic life.”Footnote 39 By July, the liquidity ratios of German banks rose to around 7 percent.

The outbreak of World War I delayed the state's efforts to improve liquidity. Regular publications of bank balance sheets ceased, and the Reichsbank reported no longer having “a well-rounded picture of our economic situation.”Footnote 40 Throughout much of the conflict, Germany was able to maintain investors’ confidence even with the departure of the Reichsmark (RM) from the gold standard in 1914.Footnote 41 Yet, after the loss in 1918, the government had to confront the problems of both reparations and exchange-rate instability. Despite adjustments to the reparations bill, including the plan outlined by the London Schedule of Payments in May 1921, many officials still believed that any long-term financial stabilization was contingent on political negotiations.Footnote 42 Preserving national security remained part of this assumption. Following the assassination of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau and the Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr—the latter overburdening the government's budget through the continued payment of public pensions—a collapse in confidence engendered the subsequent hyperinflation.Footnote 43

Solutions to the hyperinflation emerged from both domestic and international reforms. An emergency currency (Rentenmark), backed by land mortgages, offered investors a guarantee against the issuance of further notes in November 1923, while an international consortium of bankers, economists, and state officials formulated the 1924 Dawes Plan for rehabilitating the German banking system and facilitating reparation payments through the Agent General.Footnote 44 An 800 million Goldmark loan achieved a temporary stabilization of the financial sector, in addition to guaranteeing transfer protection for commercial claims.Footnote 45 As foreign support helped to quell the hyperinflation, it also provided Germany with new legal institutions for managing domestic credit. In August 1924, a new bank law brought Germany onto a gold-exchange standard, thereby affirming the principles of the Brussels (1920) and Genoa (1922) Conferences. The Reichsbank itself obtained a monopoly over the issuance of notes.Footnote 46 Its general council (Generalrat), half of which was to be composed of non-German members, intended to formalize the central bank's independence from the national government, while also keeping public finance under foreign supervision.Footnote 47

The Reichsbank and Domestic Liquidity

While Wilhelmine Germany offered a potential framework for banking supervision, Weimar Germany added the institutional impetus. An interventionist policy was the government’s response to the unresolved problems facing the national economy. For one, public spending, as measured by real wages, continued to rise throughout the 1920s such that budget deficits after 1925 had to be financed by surpluses from prior years.Footnote 48 In the realm of monetary policy, the money supply increased rapidly following the Dawes Loan, which permitted foreign credits to be used as payment for German imports.Footnote 49 Germany, in contrast to much of the prewar era, had become a net importer of capital.

Consequently, the Reichsbank supported a wide range of tactics to ensure financial stability. Already on April 7, 1924, it had declared a credit freeze on the volume of discounted bills (except in certain industries) to prevent inflation.Footnote 50 Other measures, such as the Capital Flight Law (1919) and the Law on Deposit Banking (1925), addressed some of the state's existing concerns over liquidity, while also avoiding the implementation of regulations across the entire banking sector.Footnote 51 Additionally, there were opportunities to use less direct measures for encouraging the banks to limit their intake of foreign capital.Footnote 52 In 1926, for instance, the general council suggested an amendment to the 1924 Bank Law: if direct loans to businesses were not feasible, then the Reichsbank itself needed to help cover short-term loan requirements to banks by issuing additional Treasury bills.Footnote 53 This proposal was ultimately rejected by the Reich Economic Council.

Nevertheless, the need for financial-sector reform had begun to gain wider support. Nineteenth-century economists, including Gustav von Schmoller and Max Weber, had introduced the study of the economy as a unit of analysis, although they remained outside the direct channels of policymaking.Footnote 54 After World War I, Weimar Germany witnessed the continued endurance of “academic politics” (Gelehrtenpolitik), through which economic experts exerted greater influence.Footnote 55 One such individual was Nordhoff, who had joined the Reichsbank's statistical division in 1912. He had worked at a Hamburg-based bank prior to writing a dissertation at the University of Halle on the German bill of exchange. In October 1924, he wrote about the need for greater involvement by the central bank to limit speculative credit in the domestic economy. Doing so, he argued, was vital for controlling inflation that derived from the new inflows of foreign capital.Footnote 56

Indeed, the main concern was the declining levels of cash and gold reserves in the domestic banking system, coupled with the high degree of dependence on foreign capital. Improving domestic liquidity was operationally possible through the Gold Discount Bank (Golddiskontbank), which had provided credits to German companies since 1924. At a meeting of the general council on 27 May 1927, Reichsbank president Hjalmar Schacht, advised by Sir Charles Addis (a director at the Bank of England), advocated altering the Gold Discount Bank's responsibilities.Footnote 57 After a series of discussions on the legality of its operations, which overlapped with those of the Reichsbank, its role was expanded in response to the liquidity issue.Footnote 58 It planned to continue financing the import of raw materials alongside its new responsibilities: granting sterling-based credits; providing emergency relief to agriculture; and discounting one-signature, short-term bills.Footnote 59 Schacht further envisioned the Gold Discount Bank establishing greater control over the domestic money market.Footnote 60

Later that month, a stock market crash tested the Reichsbank's ability to manage the organization of national credit. According to Hans-Joachim Voth, Schacht was misguided in his attempts to control the inflows of foreign investments through interest rate hikes since they only further contracted the supply of credit in the money market.Footnote 61 The justification, however, came from a widespread interest to curb speculative investments and stop the diversion of capital from the real economy.Footnote 62 Schacht also wanted to make banks hold more liquid assets. He often noted that while short-term capital inflows were important for rebuilding industry, they destabilized the domestic economy if used for nonproductive investments.Footnote 63 Thereafter, the Reichsbank publicly campaigned for additional credit rationing as a means of controlling foreign borrowing.Footnote 64

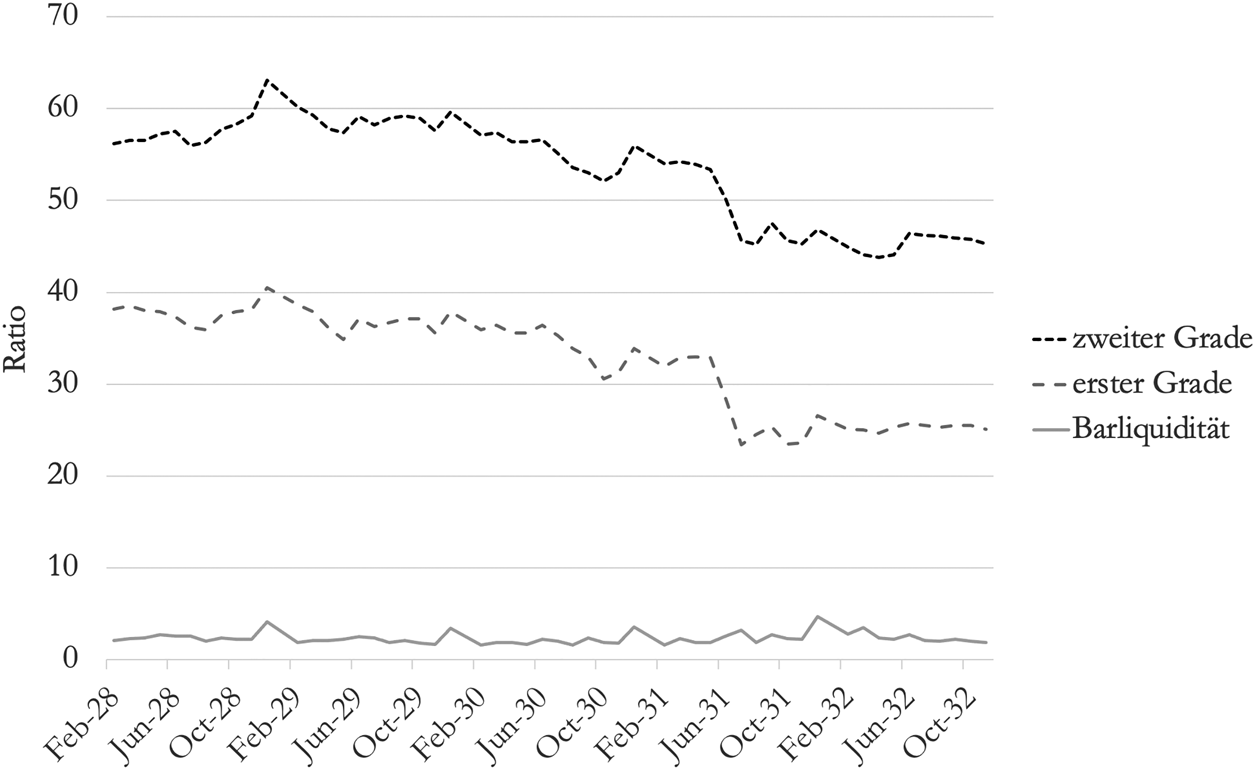

In these instances, liquidity emerged as a more defined object of analysis. A desire to gain a better understanding of liquidity in the banking sector coincided with efforts to expand the role of the state in economic affairs. Already in 1925, the Reichsbank had recommenced the publication of its own balance sheets. Given the inadequacy of existing statistics, it sought to procure additional data from banks, including more detailed information on their assets, such as the quality of bills and their maturity dates. As Nordhoff wrote, “bimonthly balance sheets as a barometer of economic activity . . . provide a picture of the general German credit-market position . . . and, thus, clues for the general direction of the monetary policy to be adopted.”Footnote 65 By March 1928, the government (at the behest of the economics minister) once again required the banks to publish interim balance sheets.Footnote 66 Data from the monthly reports of the Great Banks showed a continued decline in several liquidity ratios (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Liquidity ratios of the Great Banks. Note: The liquidity ratios of the Great Banks are calculated as follows: the cash liquidity (Barliquidität) ratio = cash/deposits; the first-degree liquidity (erster Grade) ratio = (cash + bills of exchange)/deposits; the second-degree liquidity (zweiter Grade) ratio = (cash + bills of exchange + advances + marketable securities)/deposits. (Sources: Karl Nordhoff, “Über die Liquiditätsfrage” [On the liquidity question], in Untersuchung des Bankwesens 1933, part 1, vol. 1 [Berlin, 1933], 491; Erich Schneider, “Die Liquidität der Berliner Großbanken in den Jahren 1928 bis 1932” [The liquidity of Berlin's Great Banks in the years 1928 to 1932] [Ph.D. diss., Universität Rostock, 1934], 33.)

One interpretation of declining levels of liquidity was less credit available to the industrial and agricultural industries.Footnote 67 Steel companies, for instance, depended on external financing to pay their relatively high wages and tax burden.Footnote 68 Such was the case for the industrial behemoth Thyssen AG, which had to procure loans primarily from private US banks.Footnote 69 After the hyperinflation, debt financing became more difficult as banks were increasingly reluctant to extend loans, with the board of Deutsche Bank even considering the existing terms of their loans to be far too generous.Footnote 70 Yet even if German industrial finance had become more reliant on foreign sources of capital, Reichsbank officials were more concerned with the stability of the financial sector. There was certainly a dilemma between increasing liquidity and lowering the influx of foreign funds in an attempt to curb speculation. The former involved lowering interest rates to make credit more available, while the latter necessitated raising rates to deter another speculative boom. Accordingly, the government needed to find a policy that reconciled the seemingly contradictory goals of improving banks’ liquidity ratios and limiting their dependence on foreign capital. In an effort to reduce the balance-of-payments deficit, the Reichsbank began to offer liquidity through domestic channels. To this end, the purchase of 240 million RM in mortgage securities through the Gold Discount Bank aimed to support the agricultural sector.Footnote 71

Yet a reliance on overseas capital persisted. Reichsbank vice president Friedrich Dreyse noted the ineffectiveness of discount policy due to the lack of domestic sources of capital.Footnote 72 Since 1924, banks had welcomed the influx of foreign loans, the total volume of which outpaced the Reichsbank's gold- and foreign-exchange reserves, as well as the volume of bills of exchange circulating in Germany, by 1926.Footnote 73 The Reichsbank estimated that the total short-term foreign credits between 1924 and 1930 were around 14 billion RM, half of which were debts held by the commercial banks.Footnote 74 As Isabel Schnabel has shown, this dependence increased the risk of a liquidity crisis because withdrawals by foreign depositors would have further destabilized the exchange rate.Footnote 75 Additionally, investors held accounts denominated in foreign currencies (primarily to lower the exchange-rate risk associated with foreign investments) and usually with short-term maturities (between one and three months), factors which raised the possibility of a sudden withdrawal of funds at the first sign of a crisis.Footnote 76

To what extent, however, was the liquidity problem a product of conditions abroad? Even if contemporaries criticized the apparent “foreignization” of German companies, many of the banks’ problems stemmed from developments at home. The savings banks had since 1908 cleared transactions through a network of clearing bank houses, and by 1927 the cooperative banks had established their own similar giro system.Footnote 77 These innovations, in tandem with the development of a system of cashless payments, permitted banks to hold lower cash reserves at any given moment, thereby decreasing their reported levels of liquidity.Footnote 78 Some cooperative banks also chose to invest their excess cash reserves through the Prussian Central Cooperative Fund, which suffered its own liquidity crisis at the end of 1927.Footnote 79 While the movement of funds allowed for more flexibility by transferring credits between customers’ accounts, it also exposed the system to greater risks. A significant asset–liability mismatch arose as short-term withdrawals of cash began to surpass long-term holdings of debt.

Yet because the savings banks and cooperative banks primarily served domestic borrowers and depositors (including households, farmers, and small businesses), it was instead the private, Berlin-based Great Banks that bore the brunt of criticism. They had by far the largest proportion of capital from foreign depositors, and the Statistical Office estimated that foreign investors comprised 30 percent of all their bank deposits at the end of 1929.Footnote 80 The short-term foreign debts of the Great Banks had also increased from 2.18 billion RM in April 1927 to 3.74 billion RM in September 1928.Footnote 81 These adverse developments were worsened by structural changes in the banking system, namely a series of mergers that led to the consolidation of the Great Banks from nine institutions in 1913 to six by 1929.Footnote 82 Additionally, competition among the banks had forced them to declare higher dividends throughout the 1920s, thereby weakening their liquidity base.Footnote 83 From 1926 to 1929, Deutsche Bank and Dresdner Bank had offered dividend rates of 10 percent, Commerzbank of 11 percent, and Darmstädter und Nationalbank (Danatbank) of 12 percent.Footnote 84 They later defended these rates as a way of raising investors’ confidence. As one representative from the Central Association of German Bankers later reported, “the banks . . . must attach great importance to the greatest possible continuity and stability of dividends. This principle is unchallenged in all cultured countries and particularly pronounced in England, where high dividend rates were maintained in the crisis to the end.”Footnote 85

By the late 1920s, confidence in the economy, both at home and abroad, began to deteriorate. German officials were convinced of the need for reform but were divided over the means of achieving it. For some, reparations exacerbated the liquidity problem. During a cabinet meeting in 1928, Schacht ascribed the strains of industrial performance to the burden of reparation payments outlined under the Dawes Plan.Footnote 86 For him, financial stability was closely linked with geopolitics. That the government had an incentive to prove its financial difficulties is apparent from the political controversy over reparations in accordance with the new terms of the 1929 Young Plan.Footnote 87 Due to the plan's provisions that gave priority to reparation payments over commercial credits, Germany's standing on international markets was effectively weakened.Footnote 88 At the same time, the possibility of losing access to foreign credit prevented Chancellor Brüning from pursuing more countercyclical policies.Footnote 89 Even though a supplementary internal loan of 500 million RM, as proposed by Finance Minister Rudolf Hilferding, offered an attractive 7.5 percent interest rate and additional tax incentives, it remained severely undersubscribed at only 183 million RM.Footnote 90

Banking in Germany and Britain

When evaluating the exposure of the national economy to foreign capital, German officials frequently contrasted their own banking system with foreign ones. As the Reichsbank viewed it, if German banks “were forced to hold 15 percent cash, which is the custom in England,” then “the credit volume of the economy would be reduced accordingly.”Footnote 91 Comparisons made, notably to the British banking system, accelerated the prospect of reform at home. To be sure, on June 25, 1930, Jakob Goldschmidt, a German banker, revealed the limits of such observations: “a tendency has shown itself in Germany to consider the English system of banking to be the real goal of bankers, while in England the view has often been expressed that the German banking system is more suitable for present conditions.”Footnote 92 This opinion was in reference to the German system of universal banking, which supported industrialization by combining the traditional work of deposit banks with the long-term financing of businesses.Footnote 93 In contrast, British banks were more specialized institutions: merchant banks (private businesses that financed international trade), clearing banks (joint-stock corporations that settled transactions at a central clearing house), and discount houses (buyers and sellers of bills of exchange and government bonds). Yet the structures and problems of banking systems in both countries had begun to converge. Similar to their German counterparts, British firms reported on the widespread shortage of funds, a deficiency coined the “Macmillan gap.”Footnote 94 The British government was also concerned with whether small and medium-sized firms had been able to access sufficient capital, as well as the extent to which finance had “failed” industry.Footnote 95 This view was confirmed in the final report of the Committee on Finance and Industry (the Macmillan Committee), which aimed to investigate whether such a funding gap had contributed to overall industrial stagnation.Footnote 96

In response to concerns of inadequate lending to industry, central banks across Europe endeavored to identify new channels for improving economic statistics. The Bank of England identified itself as the institution primarily responsible for compiling such data, including the cash balances of the clearing banks.Footnote 97 Yet it would have been a mistake to rely too much on their estimates. A common and well-known practice of “window dressing” allowed the banks to move funds among one another prior to reporting their liquidity positions on different days of the week.Footnote 98 The problem of distortionary data also occurred in German reports, albeit through different means. Whereas the British banks reported on different days of the week, German banks reported at month's end, allowing them to transfer funds before the reporting date and appear more liquid than they actually were. They were, as a result, able to manipulate their annual balance sheets “to show a picture of the most fluid balance possible.” Even so, requiring balance sheets on a weekly (as done by British banks) or even a daily basis would have been “wholly impossible” to sustain from a practical standpoint.Footnote 99

The weaknesses of German banking relative to other countries, as public statistics revealed, became readily apparent to officials who continued to weigh the possibility of reform. On May 30, 1931, Nordhoff met with representatives from the economics ministry, the Prussian trade ministry, and the Association of Savings Banks. Although the attendees considered ways of supporting financial institutions, such as by lowering interest rates or amalgamating failing banks, they also expressed doubts that mergers in the eastern regions would have helped ease credit conditions. Nordhoff was opposed to any proposal that included rationalization because of the adverse “psychological effect” of exposing additional problems.Footnote 100 Instead, the emergency ordinance introduced by President Paul von Hindenburg on June 5 only ordered the banks to reduce their expenditures and lower administrative costs.Footnote 101 Yet this legislation, followed by the Reichsbank's decision to raise the discount rate on June 13, failed to prevent the ensuing liquidity crisis. As capital outflows began to undermine the gold standard, it became increasingly clear that the Reichsbank was unable to maintain adequate reserves to back the currency.Footnote 102 Even though foreign aid to Germany in the form of a $100 million loan had already been exhausted by early July, the Reichsbank rejected any plans for providing additional emergency loans to the banks.Footnote 103 Danatbank (Germany's second-largest private bank) was forced to close its doors on July 13.Footnote 104 Alongside the Great Banks, other financial institutions across the country, from cooperative banks to state banks, similarly faced the threat of bankruptcy.Footnote 105

Abroad, British merchant banks—in contrast to the clearing banks, which did not have a significant volume of acceptances in Germany—were soon vulnerable to the crisis.Footnote 106 Paul Einzig, a financial journalist, later remarked that it was “common knowledge that British banks were heavily involved in German credits.”Footnote 107 Further pressure on the British pound derived from a crisis in public finance. The final report of the Committee on National Expenditure, released on July 31, revealed the government's budgetary problems and projected a deficit of nearly £120 million in the next fiscal year.Footnote 108 Despite attempts to sustain confidence in the pound—the sale of foreign-exchange reserves, the announcement of a bank holiday, and the procurement of an emergency loan—the Bank of England was forced to abandon the gold standard in September.Footnote 109

Retrospective examinations of 1931 have debated whether Germany suffered a banking crisis or a currency crisis. Several scholars have identified how the liquidity problem exacerbated both a domestic bank run in Germany and the subsequent sterling crisis.Footnote 110 Since 1924, structural weaknesses among German banks, notably the Great Banks, had come from their speculative investments in high-risk and low-profit industries.Footnote 111 Still other explanations for the crisis have focused on domestic politics: Germany suffered from a currency crisis that was worsened by political choices, namely the decision to remain on a gold standard.Footnote 112 Had Brüning made different policy choices, according to these arguments, the crisis might have been resolved sooner or been less severe. Yet it is difficult to reconcile this thesis in light of the fragility of the banking sector, especially when compared with other countries that also adopted the gold standard or ran budget deficits. Since the prewar years, nearly all financial institutions in Germany reported declining levels of liquidity, and it was widely known that they had been much less liquid than their foreign equivalents.Footnote 113 The cash-liquidity ratio of the Great Banks decreased from 7.4 percent in 1913 to 5.3 percent by 1931 and 3.5 percent the following year, while that of the British clearing banks consistently remained around 11 percent.Footnote 114 Estimates by the League of Nations showed that the liquidity ratios of banks in France and the United States were also relatively high and even increased after 1931.Footnote 115 Moreover, German banks were particularly susceptible to bank runs since foreign depositors were more likely to withdraw their short-term funds (“hot money”).Footnote 116 Officials thus speculated that a sudden devaluation of the Reichsmark might have precipitated fear-induced capital outflows, which could have culminated in another hyperinflation.Footnote 117

Interventions and Reform

Precisely because the banking system had been susceptible to foreign withdrawals of capital, the German monetary authorities advocated a sharp response through financial-sector reforms. Already in place were capital controls, enacted on July 15, 1931; bank holidays lasting until August 5; and the first two Standstill agreements, which froze the repayment of short-term foreign claims.Footnote 118 At a meeting of the Friedrich List Society in September, Wilhelm Lautenbach from the economics ministry proposed a reflationist policy of credit expansion and wage reductions. This internal devaluation—whereby lower prices made goods more competitive abroad—meant Germany would have been able to maintain parity with gold, a policy viewed as a self-stabilizing mechanism.Footnote 119 Even more radical than the Lautenbach Plan was the proposal of Ernst Wagemann, president of the Statistical Office, who advocated a major restructuring of the banking system and a greater expansion of credit, much to the dismay of the anti-inflationary Reichsbank and cabinet.Footnote 120 Meanwhile, British officials offered less urgent assessments of their own banking system. One of the Bank of England's economists, Henry Clay, reported that, if anything, “[the banks] have been too generous, too ready” to offer loans.Footnote 121 Thus, industrial support through rationalization had been prioritized over financial-sector reform (Table 2).Footnote 122

Table 2 Select Interventions in Germany and Britain

Sources: On German interventions, see Hasse, “Die Krisenmaßnahmen des Jahres 1931,” 74–76; Born, Die deutsche Bankenkrise, 118; Manfred Pohl, “Die Liquiditätsbanken von 1931” [The liquidity banks of 1931], Zeitschrift für das gesamte Kreditwesen 27, no. 20 (15 Oct. 1974), 929. On British interventions, see Committee of Treasury, Minutes, 30 Jan. 1929, G8/58, Bank of England Archives, London; Henry Clay, Lord Norman (London, 1957), 336–338; R. S. Sayers, The Bank of England, 1891–1944, vol. 1 (Cambridge, UK, 1976), 318–327; Carol E. Heim, “Industrial Organization and Regional Development in Interwar Britain,” Journal of Economic History 43, no. 4 (1983), 937–941; Michael Collins, Banks and Industrial Finance in Britain, 1800–1939 (Cambridge, UK, 1991), 78–79.

Contrary to the non-statutory interventions in Britain, Germany implemented several financial-sector reforms. The new Acceptance and Guarantee Bank, established on July 28, 1931, provided endorsements on bills of exchange that were then rediscounted by the Reichsbank. By extending credits to Danatbank and other banks, it effectively deterred the implementation of more radical proposals of reflation. At the same time, German officials wanted to avoid imposing an overly stringent system of regulation as had been established elsewhere. Although the United States, for instance, appeared to have “the longest history of banking supervision and strict banking legislation,” the rules exercised by the federal and state governments were “quite inconsistent.”Footnote 123 Thus, only an emergency ordinance followed as a temporary expedient to address the liquidity shortage by requiring savings banks to hold a certain percentage of their deposits in liquid assets.Footnote 124 These more conservative efforts had an important precedent, as the tools of the Acceptance and Guarantee Bank in 1931 mirrored those of the Gold Discount Bank in 1927, which included discounting bills and providing industrial credits. Other projects, such as the German Financing Institute and the Amortization Fund for Commercial Loans in December 1932, aimed to increase liquidity by purchasing additional assets from private banks.Footnote 125

Additional impetus for legal reform came at the behest of Schacht in June 1933.Footnote 126 A formal examination of the banking sector commenced later that year through the hearings of the Committee of Inquiry into the Banking System. For more than a year, both the internal proceedings and the external testimony from 123 experts covered a wide range of issues, including the conditions for instilling trust in the system, the organization of the banking sector, and the national shortage of liquidity.Footnote 127 The investigation effectively brought bankers, lawyers, economists, and civil servants together to discuss the extent to which insufficient liquidity had exacerbated the crisis. A preliminary draft of the Reich Banking Law, written by the Reichsbank in November, addressed the most important provision from the hearings, namely the requirement of banks to maintain (after a transition period) a minimum cash-liquidity ratio of 10 percent.Footnote 128 To limit speculation, new prohibitions on the savings banks sought to distinguish between their operations (accepting deposits and providing savings accounts) and the investment activities of the Great Banks (underwriting securities for larger firms), a separation analogous to the one defined by the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act in the United States.Footnote 129

In May 1934, a more comprehensive version of the Reich Banking Law returned to the liquidity concern by stating that “sufficient cash liquidity is an absolute requirement for the credit system.”Footnote 130 More concretely, it delineated the responsibilities of the new Credit Supervisory Office, such as setting new reporting requirements and enforcing penalties for noncompliance.Footnote 131 By November, Schacht folded many of these clauses into a single law, which he planned to present to the cabinet.Footnote 132 There were relatively few changes between the November report and the December legislation that Hitler's government enacted. Aside from a few minor adjustments, the new draft now stipulated that the Reichsbank was able to issue its own rules regarding the publication of the banks’ monthly balance sheets.Footnote 133 It also included more details on new licensing and disclosure requirements for banks.

Similar to the 1908 Bank Inquiry, the 1933–4 Committee of Inquiry confronted the longstanding debate over the state's responsibilities in private affairs. “It cannot be the task of the state to restrict the management of the credit institutes to such an extent that the state determines the business policy of the credit institutes,” proclaimed Schacht, “but leaves the responsibility and bearing of risk to the credit institutes themselves.”Footnote 134 Even so, the general view of regulation became linked to the wider effort of financial modernization. At the Reichsbank, Nordhoff stressed the importance of improving the liquidity of domestic banks to the level of banks in Britain, where the liquidity ratio “averages around 11–12%.”Footnote 135 These comparisons served to justify intervention by the German monetary authorities. Banking supervision abroad often fell under the authority of the finance ministry or a separate government authority, while a few countries—for instance, Italy and the United States—conferred regulatory powers to an independent central bank.Footnote 136 Elsewhere, such as in Sweden, an independent body enforced liquidity requirements and standardized reports.Footnote 137 Through these comparisons, some onlookers were inclined not to emphasize the well-developed nature of regulation in other countries but rather to cite the lack thereof. “A comprehensive legal regulation of the deposit banking system,” wrote one Reichsbank official, “exists as little abroad as in Germany.”Footnote 138 State intervention, in this regard, might have allowed Germany to be a leader for others.

In many respects, the Reich Banking Law preserved numerous aspects of the financial system. The government planned to keep the existing banking network largely intact—as opposed to separating the system into regional banks, as some suggested—while also setting minimum-liquidity requirements, maximum limits on lending, and licensing requirements.Footnote 139 These features sought not to eliminate private banking but rather to establish a general system of state oversight. For Hans Rummel of Deutsche Bank, the Reich Banking Law had “far-reaching effects” yet also improved the functioning of the overall banking system by treating all financial institutions “equally” under the law.Footnote 140 Moreover, officials were able to adapt the new regulation into the existing legal framework of the Weimar Republic. The position of the Reich Commissioner for the Banking Industry, having been created in September 1931, reported to the economics ministry. While the new office was meant to be for the state (“an institution under public law that exercises economic administrative powers”), it had yet to be determined whether it was to be of the state, directly beholden either to a government ministry or to the banking sector.Footnote 141 Subsequent compromises with Nazi politicians thus featured into the legislation, such as the Reich Commissioner being chosen by the Führer (head of the Nazi Party) and by the Reichskanzler (head of government) only after consultation with the Reichsbank president.Footnote 142

Despite its timing, the Reich Banking Law was not a product of Nazi policy.Footnote 143 Had the Third Reich been fully in control of reform efforts in 1934, there could have well been a nationalization of the entire banking system.Footnote 144 Instead, for one official, the political shifts provided the Reichsbank with an opportunity to justify its control over domestic credit: “In the National Socialist state, . . . the reawakening of the sense of honor, the emphasis on personality values, [and] the tight structure of the state . . . give the opportunity to reevaluate the character traits of the borrower to a greater extent as a basis of credit.”Footnote 145 Banking regulation institutionalized existing efforts to address inadequate liquidity and foreign dependency, a solution made compatible with Nazi rhetoric over state intervention. Only separately were there attempts to subsume the new legislation under the apparatus of the Third Reich, notably when the Academy for German Law began its investigation into “whether the legal areas of the banking and stock exchange law . . . correspond to the basic views of the National Socialist state.”Footnote 146

Conclusion

The German monetary authorities crafted the Reich Banking Law to bring once-indirect forms of financial supervision into a new regulatory framework. Although regulation at a fundamental level might have aimed to maintain financial stability, the structures that could have been designed had depended on changing perspectives regarding state involvement. The existing statistics on deficient cash reserves and the prevalence of foreign exposure not only encapsulated the anxieties of officials who sought to measure the liquidity of the financial sector but also directly led to the construction of a regulatory policy. Having confronted the liquidity problem in the pre-crisis years—and only later influenced by the events of 1931 and 1933—German officials made the state responsible for credit policy and oversight. For Leopold Scheffler, an adviser at the Reichsbank, a new chapter in state intervention had been written: “The importance of the Reichsbank as the central bank for economic life is based on its given possibilities to expand or narrow credit volume. As the last liquidity reserve of the German organization of credit, it is therefore referred to as the ‘bank of banks.’”Footnote 147

Banking regulation thus evolved from an amalgamation of legal reasoning, foreign comparisons, national security, and institutional impetus. It was not a given that the state needed to regulate the banking sector in response to a singular financial (or political) crisis. Nor was there even a perpetual desire to assert more state control given the persistence of classical liberalism, which continually converged around the idea of limited state involvement. An alternative policy might have been drawn from comparisons with Britain, where the government avoided imposing banking regulation. Similarly, there were some commonalities with the federalized financial system in the United States, where state and national jurisdictions conflicted with one another.Footnote 148 Yet, more specific to Germany, the creation of a regulatory policy was based on the extensive national security debates over concerns of an illiquid banking sector, one that was increasingly vulnerable to foreign crises. Both the 1908 and 1923 crises demonstrated the possible use of informal financial-sector supervision as an extension of domestic security. By 1934, the Third Reich had inherited a range of supervisory instruments and legal frameworks, which determined the structure of its own politico-economic governance. Attempts by the government and central bank to address the inadequate levels of liquidity persisted well into the postwar years, particularly when minimum-liquidity ratios became a widespread tool for banking supervision.Footnote 149

Further research may consider placing the development of German banking within the wider literature on the history of capitalism. Numerous regulatory configurations, ranging from the decentralized Federal Reserve System to the Bank of England's continued use of informal pressure, were possible. Werner Plumpe has theorized about a particular variant of German capitalism, which arose from an enduring tradition of the state to maintain order in crises.Footnote 150 In line with this theory, the emergence of a regulatory policy may appear not as a product of economic rationality but rather as an outcome of historic traditions and cultural practices specific to Germany. This interpretation, along with other recent works on this topic, offers a compelling way of assessing the many conceivable levels of political involvement.Footnote 151 A study of regulation must consider the array of options before civil servants, bankers, lawyers, and economists in determining policy. By contending with the various proposals for greater financial supervision, whether direct or indirect, German officials enacted a series of reforms that redefined the role of the state in the economy.