Introduction

Advance Care Planning (ACP) “supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care. The goal of ACP is to help ensure that people receive medical care consistent with their values, goals, and preferences during serious and chronic illness” (Sudore et al., Reference Sudore, Lum, You, Hanson, Meier and Pantilat2016, p. 821). ACP empowers older adults to plan for a future when they can no longer make their own decisions (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2006). In addition to discussing one’s wishes and values with regard to medical care, ACP also encompasses creating and completing one or more of the following documents: enduring power of attorney, representation agreement, and advance directive (Government of British Columbia, 2023).

By 2036, it will be expected that approximately one fourth of the Canadian population will be 65 years of age or older, making ACP a more critical area for research than ever before (Meng & D’Arcy, Reference Meng and D’Arcy2014) given the age–mortality link (Dolejs & Maresova, Reference Dolejs and Maresova2017). ACP decreases the burden on the health care system, as it prevents unnecessary and undesired end-of-life care (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2019).

Although 92 per cent of physicians in a United States study (Fulmer et al., Reference Fulmer, Escobedo, Berman, Koren, Hernández and Hult2018) reported that ACP discussion is crucial, as it communicates the individual’s values and preferences, Kulkarni, Kulkarni, Karliner, Auerbach, and Pérez-Stable (Reference Kulkarni, Kulkarni, Karliner, Auerbach and Pérez-Stable2011) found that only 40 per cent of participants engaged in ACP discussion and that individuals from ethnic minorities, regardless of their ethnicity, education, and age, have a low rate of ACP engagement. Kwak and Haley (Reference Kwak and Haley2005) determined that ethnic groups, such as the South Asian (SA) community, the focus of our study, lacked awareness of ACP and were less likely to complete supporting documents associated with it, highlighting the need for culturally friendly approaches to engage ethnic minorities in ACP.

Under-representation and Misconceptions

SA communities, including Indian, Pakistani, and Sri Lankan, are among the largest visible minorities in Canada and the fastest-growing immigrant population in other Western countries (Biondo et al., Reference Biondo, Kalia, Khan, Asghar, Banerjee and Boulton2017; Statistics Canada, 2013; United Nations, 2015). Despite being one of the most populous minorities, SAs report far lower satisfaction with their health care than the general population, stating that their dissatisfaction is partly the result of their health care provider’s failure to understand their values (Periyakoil, Neri, & Kraemer, Reference Periyakoil, Neri and Kraemer2016; Yarnell, Fu, Bonares, Nayfeh, & Fowler, Reference Yarnell, Fu, Bonares, Nayfeh and Fowler2020) which are core to ACP.

The concept of ACP originated in the United States and has been heavily influenced by Western cultural norms, therefore making it less meaningful for ethnic minorities, such as the SA community, who are unfamiliar with these Western world concepts (Kwak & Haley, Reference Kwak and Haley2005; Sabatino, Reference Sabatino2010). Menon, Kars, Malhotra, Campbell, and van Delden (Reference Menon, Kars, Malhotra, Campbell and van Delden2018) found that although ethnic minority populations are interested in ACP, they face many barriers that stop them from completing it. These authors argue that minority populations are less engaged and accepting of ACP discussions because of cultural and religious norms, and that there is a tendency to deflect their decision making about end-of-life care onto physicians and family.

Whereas Biondo et al. (Reference Biondo, Kalia, Khan, Asghar, Banerjee and Boulton2017) found that the older SA population believes that physicians should initiate ACP discussion, which in turn may lead to document completion, Thorevska et al. (Reference Thorevska, Tilluckdharry, Tickoo, Havasi, Amoateng-Adjepong and Manthous2005) determined that only 7 per cent of patients (ages 19–97) created living wills in consultation with a physician compared with the 76 per cent of patients who had created one with their lawyers. Further, patients shared their end-of-life directives most frequently with their family (94%), followed by their lawyers (73%), whereas only 29 per cent of patients shared these with their physicians. Additionally, Thorevska et al. (Reference Thorevska, Tilluckdharry, Tickoo, Havasi, Amoateng-Adjepong and Manthous2005) found that patients with living wills failed to comprehend the “life-sustaining therapies” included in their advance directives. This failure may partly be the result of patients choosing to engage in ACP with their lawyers and families while leaving their physicians out of the discussion; therefore, they may be provided with unwanted care.

Physician and Patient Barriers

Periyakoil et al. (Reference Periyakoil, Neri and Kraemer2016) found that 91 per cent of Asian -American and 85 per cent of African American physicians reported barriers to conducting ACP discussions with patients in their practices. Of particular interest, 86 per cent reported difficulty conducting ACP discussions with ethnicities different from their own. The physicians cited the following as the most frequently experienced barriers to ACP delivery to ethnic minorities: the patient and family’s religious and spiritual beliefs surrounding death, cultural deviance from the norm during decision making, difficulty interpreting technical language, lack of knowledge, and lack of trust in physicians and the health care system. They also discussed their failure to address patients’ cultural beliefs, values, and practices as key barriers. Fulmer et al. (Reference Fulmer, Escobedo, Berman, Koren, Hernández and Hult2018) found that only 29 per cent of physicians were formally trained in ACP, and that only half felt educationally prepared to conduct ACP discussions. They also expressed reluctance to engage in ACP because of a lack of time availability and the desire to maintain patient’s hope while preventing any feeling of discomfort.

Yarnell et al. (Reference Yarnell, Fu, Bonares, Nayfeh and Fowler2020) found that ethnic minorities, such as SAs, experience significantly more extreme care measures (e.g., resuscitation, feeding tubes, cardiopulmonary resuscitation) than the general population. They attribute this to difficulty in patient–physician communication, reduced access to palliative care services, or varying end-of-life perspectives and understanding.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented many challenges for older adults, with greater risk and higher mortality rates among those with co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (Sanyaolu et al., Reference Sanyaolu, Okorie, Marinkovic, Patidar, Younis and Desai2020) diseases more common among older adults (Shahid et al., Reference Shahid, Kalayanamitra, McClafferty, Kepko, Ramgobin and Patel2020). Furthermore, a growing body of research has shown that the COVID-19 pandemic has more adverse consequences for older adults who belong to ethnic minorities, because they have a higher risk of COVID-related health concerns and inadequate health care access and quality (Garcia, Homan, García, & Brown, Reference Garcia, Homan, García and Brown2021). This ongoing pandemic has had a profound effect on the mental health of older adults, too, as many communities are following social and physical distancing rules to reduce the spread of the virus. Given that older adults are especially susceptible to the disease, they are advised to engage in strict isolation protocols leading them to report greater loneliness and higher depression rates following the onset of the pandemic (Krendl & Perry, Reference Krendl and Perry2021). The COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected older adults’ mental health and social well-being in the short term.

It could be speculated that engagement in ACP would have increased because of a higher perceived risk of disease and death in older adults resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, because of the extensive media coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic, older adults became more aware of the severity and potential consequences of COVID-19 and therefore, would be more likely to engage in ACP completion. For example, Jones (Reference Jones2021) found that 33 per cent of adults in the United States reported the pandemic as a trigger for end-of-life discussions. Alternatively, discussions and document completion might be delayed, as older adults prioritized social distancing and self-isolation. A survey of adults 55 years of age and older conducted by Gutman, de Vries, Beringer, Daudt, and Gill (Reference Gutman, de Vries, Beringer, Daudt and Gill2021) found that whereas 43 per cent of the total sample had engaged in ACP discussions prior to the pandemic, most of these discussions were with spouse/partners, with only 5 per cent being with a physician. The pandemic stimulated patient–physician ACP discussion, but this led only to an additional 2 per cent. Amongst the SA respondents, none reported ACP discussions with a physician before or during the pandemic (Gutman et al., Reference Gutman, de Vries, Beringer, Daudt and Gill2021).

Research Questions

This study aimed to understand initiation and participation patterns, topics covered, barriers, and facilitating factors that physicians encounter when initiating or conducting ACP discussions with SA patients. We also wanted to investigate physician training in ACP facilitation and the use of ACP tools by Primary Care (PC) physicians and hospitalists. And we were interested in the impact of COVID-19 on physicians with respect to ACP with the SA population. Specific research questions were:

-

• Do PC physicians and hospitalists adopt similar or different approaches when engaging in ACP discussions with SA older adults?

-

• Do PC physicians and hospitalists identify similar or different barriers and facilitating factors when conducting ACP discussions with this minority population than when conducting these discussions with white patients?

-

• Do PC physicians and hospitalists have comparable ACP training and use tools to the same extent?

-

• Do PC physicians and hospitalists report that the COVID-19 pandemic affected ACP discussions equally?

We speculated that there might be differences in approach used by the two types of physicians, because hospitalists have a shorter period of time with patients in which to build rapport and deal with patients’ concerns around ACP than do PC physicians.

This study is part of a larger national project entitled “iCAN-ACP.” Its objective is to increase uptake, impact, and access to ACP among older Canadians living with frailty across the PC, long-term care, and hospital sectors. In focus groups with SA and Chinese older adults (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Gutman, Beringer, Kwan, Jang and Vashisht2019a), the team has explored ways of increasing the cultural relevance of approaches and tools supporting ACP and challenges related to participating in ACP. Additionally, the team conducted interviews with physicians to obtain an understanding of their experience in engaging in ACP discussion with the SA, Chinese, and LGBTQ+ populations. This article describes findings from an expanded study of physicians serving the SA population.

Methods

Data for this research came from interviews with physicians with a practice comprising 15 per cent or more of SA patients 55 years of age and older, conducted at two points in time. The study commenced in 2020 with the first set of interviews (n = 12) conducted pre-pandemic between January and April. The sample was expanded, and a second set of interviews (n = 10) were conducted between May and October 2021. There was a total of 22 interviews, 11 with PC physicians and 11 with hospitalists, with one of the physicians interviewed twice, once as a PC physician and once as a hospitalist. The first author conducted one of the 2020 interviews and all of the 2021 interviews and had primary responsibility for the analysis of all interviews. This study was approved by the Simon Fraser University Research Ethics Review Board (approval number 2019s0302).

Interview Guide

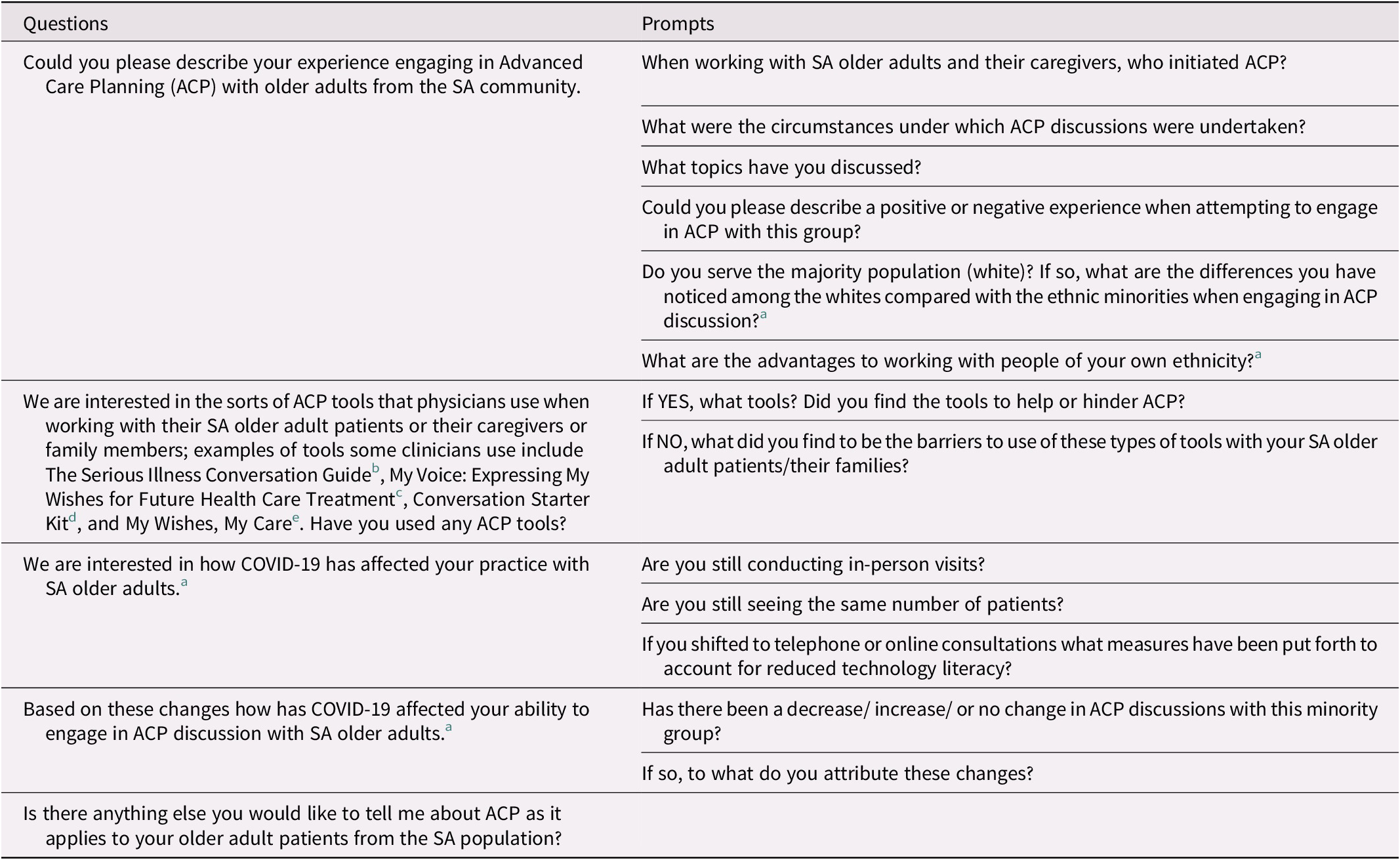

The 2021 interview guide consisted of the same three open-ended questions as the 2020 interview guide, with the addition of a question centred around culture congruence

between physician and patient and two centred around the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). The first three questions and prompts explored the physician’s experiences with SA older adults regarding ACP and their utilization of ACP tools. The additional questions aimed at understanding how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced physicians’ practice and its effect on their ability to engage in ACP discussions.

Table 1. Interview guide and prompts

Note.

a Question added to 2021 interview guide.

b © 2015, Ariadne Labs: A joint Centre for Health System Innovation (www.ariadnelabs.org) and Dana Farber Cancer Institute. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-CommercialShareAlike4.0 International Licenses http://Creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/Revised 22 May 2015

c My Voice:Expressing My Wishes for Future Health Care Treatment. Available at https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/family-social-supports/seniors/health-safety/advance-care-planning

d © 2021. The Conversation Project – an Initiative of the Institute for Health Care Improvement. http://www/theconversationproject.org

e British Columbia Centre for Palliative Care https://www.bc-cpc.ca/all-resources/community-organizations/mywishesmycaretoolkits/

Recruitment

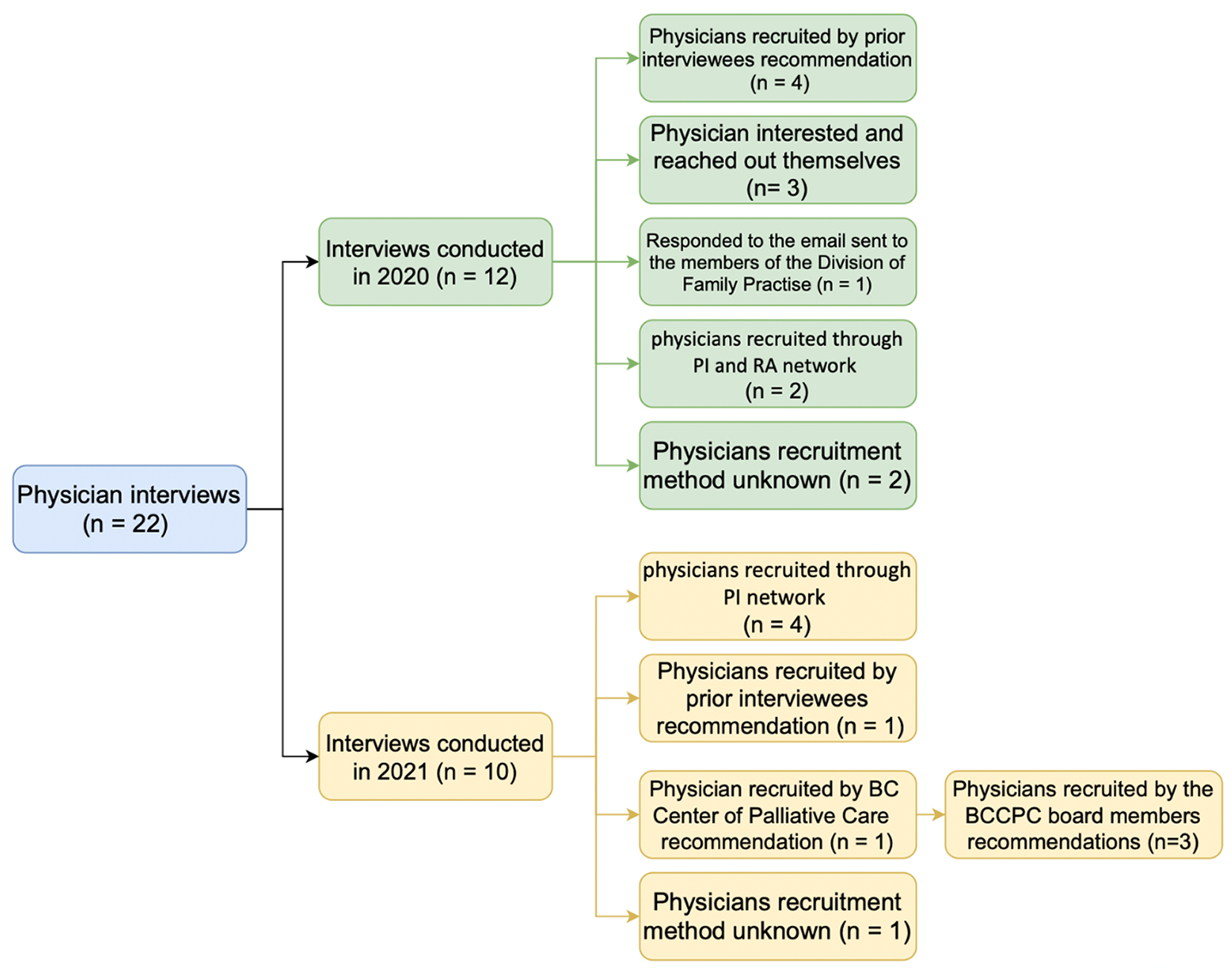

Various recruitment methods were utilized in both the 2020 and 2021 interviews (Figure 1). These included approaching the research staff’s social networks to connect with physicians willing to participate. Some physicians expressed interest in participating after coming across the study’s recruitment flyer e-mailed to them by the University of British Columbia Division of Family Practice or through other physicians’ recommendations. Additional recruitment took place through the “snowball method,” whereby previously interviewed physicians were asked to e-introduce the research team to their colleagues or provide contact information for colleagues whom they thought might be interested in the study.

Figure 1. Flow chart depicting the recruitment method for the 22 interviewees

The British Columbia Centre for Palliative Care was also approached to assist with recruitment. They connected the research team with a SA physician who provided e-introductions to 18 physicians. The British Columbia Community Response Network was also approached for assistance with recruiting; e-introductions to six physicians were obtained.

In both 2020 and 2021, following an expression of interest by a physician, there were generally several back-and-forth e-mails between the research staff and the physician to schedule an interview time and complete the required paperwork (consent form and participant profile). If a physician failed to respond to the first e-mail, a second e-mail was sent with “second try” in the subject line. In 2021 a third e-mail was sent with “last try” in the subject line.

Physicians were deemed eligible to participate in the study if they practised in Canada and their practice comprised a minimum of 15 per cent of SA adults 55 years of age or older, as self-reported by the physician. Both PC physicians and hospitalists were approached with the belief that PC physicians have a continuing relationship with their patients, whereas hospitalists frequently see patients for a shorter period and address more acute health concerns. Consequently, it may be inferred that ACP engagement would be different.

Interview Process

Initially, study participants could choose to have their interview conducted in person, by telephone or by videoconference over Zoom. In-person interviews subsequently were prohibited with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic. The recruitment materials indicated that participation was “by their own choice and on their own time” as an individual and not as an employee of an organization, thus obviating the need to obtain their employer’s permission. Two of the 2020 interviews were in person, four were by telephone, and six were by Zoom. Two of the 2021 interviews took place by telephone and eight took place by Zoom. All were audio recorded. The interview duration was, on average, 30 minutes. Study participants received a $25 gift card as a thank you for contributing their time and insights.

Analysis

A blended, mixed-method approach to content and thematic analysis used in prior research by members of the research team (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Gutman, Humble, Gahagan, Chamberland and Aubert2019b; de Vries & Megathlin, Reference de Vries and Megathlin2009) was utilized to analyze the physicians’ responses to the open-ended questions posed during the interview. The approach, which involved the development of a detailed codebook, includes both inductive and deductive coding, “in which an initial, a priori content analysis coding scheme based on theoretical and practical considerations was supplemented by additional codes derived in an iterant, emergent process of thematic analysis” (Neundorf, Reference Neundorf and Brough2019, p. 219). This method was applied to the 10 interviews conducted with SA physicians in 2021 and the 12 previously conducted in 2020. In terms of process, the recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim by the research staff. These transcripts served as the “raw data,” with six used to develop and test the codebook. In total, three persons coded the interviews, following establishment of reliability during the test coding. Over the course of coding, coders regularly checked in with each other to ensure and verify adherence to the codebook; discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

IBM SPSS version 22 was implemented for quantitative analysis using χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests (when assumptions of χ2 were not met) and the Mann–Whitney U Test, with α = 0.05 considered as the level of significance.

Results

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

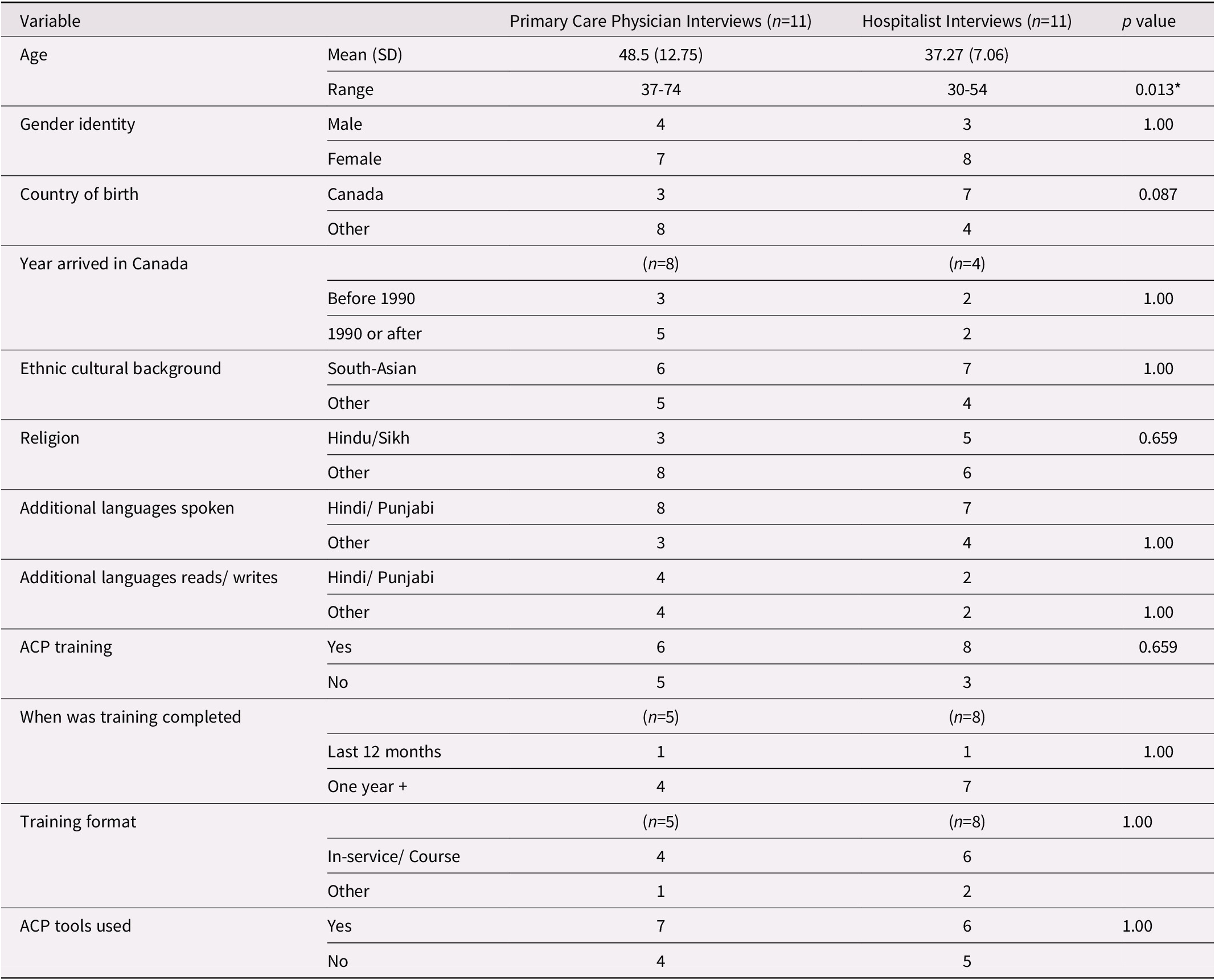

Prior to the interview, participants were asked to complete an informed consent form and a participant profile to collect demographic information as well as information concerning experience with ACP tools. As shown in Table 2, 7 of the 22 interviews were with male and 15 were with female physicians. Their ages ranged from 30 to 74 (mean age = 42.6 years; standard deviation (SD) = 10.9). The participants were born in Canada (n = 11), India (n = 5), Hong Kong (n = 2), Taiwan (n = 2), and Pakistan (n = 2). Those born outside of Canada immigrated to Canada in 1960–1969 (n = 1), 1970–1979 (n = 3), 1980–1989 (n = 1), 1990–1999 (n = 3), and 2000–2010 (n = 3). They identified their ethnocultural backgrounds as white (n = 1), Chinese (n = 5), South Asian (n = 14), Southeast Asian (n = 1), West Asian (n = 1), and Italian (n = 1). Religions practiced by the participants included Roman Catholicism (n = 3), Hinduism (n = 4), Islam (n = 3), Sikh (n = 4), Protestantism (n = 1), Buddhism (n = 2), Jainism (n = 1), and Sanatan Dharma (n = 1), with a subset reporting having no religion (n = 3), Some participants spoke Cantonese (n = 3), Mandarin (n = 3), Hindi (n = 5), and Punjabi (n = 9), in addition to English. Some participants also were able to read and write Traditional Chinese (n = 3), Hindi (n = 4), Punjabi (n = 5), Urdu (n = 3), French (n = 2), Gujrati (n = 1), Vietnamese (n = 1), and Taiwanese dialect (n = 1) in addition to English. Three participants had received specialty training in geriatrics, and one each had received specialty training in laboratory and medicine policy, hematology, medical ethics, family medicine, and general internal medicine. In addition to working in PC settings (n = 11) and as hospitalists (n = 11), participants reported working in long-term care facilities (n = 1), assisted living (n = 1), community laboratory (n = 1), community youth clinic (n = 1), and urgent care (n = 1). On average, the physicians’ practice consisted of 28.5 per cent SA older adults.

Table 2. Socio-demographic characteristics of interviewed physicians with a practice of 15 per cent or more of SA patients by type of practice

Note. *Difference statistically significant p < 0.05.

Training in ACP and ACP Tools Used

In total, 14 (64%) had received some ACP training, 2 in the past 6 months and 11 more than a year ago. For the majority (n = 6), the training was in-service or through a course (n = 5), and for the remainder, through workshops and reading (n = 3) or as part of their residency or specialty training. The training ranged from a few hours within their specialty training to a full-day workshop. ACP tools used included Serious Illness Conversation Guide (n = 10), My Voice: Expressing My Wishes for Future Health Care Treatment (n = 6), Conversation Starter Kit (n = 4), and My Wishes, My Care (n = 1).

Comparison of Primary Care Physicians and Hospitalists

PC physicians were significantly older than the hospitalists (mean age = 48.5 and 37.3, respectively, p = 0.013). More hospitalists than PC physicians were born in Canada, but the difference was not statistically significant. Additionally, more hospitalists (73%) than PC physicians (58%) had some ACP training (Table 2).

Comparison of 2020 and 2021 Interviewees

More hospitalists were interviewed in 2020 (n = 7) than in 2021 (n = 4). The 2020 physicians were younger than the 2021 physicians (mean age = 36.3 and 51.0, respectively; p = 0.002). Unlike the 2021 interviewees, Canada was the primary country of birth for most of the 2020 interviewees. Whereas more of the 2021 interviewed physicians had received specialty training, more of the 2020 interviewed physicians had received ACP training. Only the age difference, however, was statistically significant.

Interview Themes and Sub-themes

Thematic analysis of the interviews resulted in the following nine themes: fostering ACP discussions, forms and content of ACP discussion, tools and resources, physician evaluation of ACP discussion, culture, family dynamics, COVID-19, comparisons, and suggestions. Several of these, it will be noted, are over-arching or cross-cutting issues and do not reference SA culture.

Fostering ACP discussions

A majority of PC physicians and hospitalists reported that they, rather than the patient, most commonly initiated discussions, and stated “[they’ve] never ever seen a patient who would themselves bring up the topic.” They reported engaging in ACP discussions primarily “when there [is] … an indication that [patient’s] health is following a [downward] pattern … [usually] cancer patients [and] patients who have multiple comorbidities.” The second most common time ACP discussions were initiated – mentioned more frequently by PC physicians than by hospitalists – was when the physician completed government billing forms for PC services that patients had received.

Form/content of ACP discussion

Both types of physicians reported engaging in patient-centred discussions while prioritizing the patient’s wishes, goals, personal values, and meaning/ pleasure in life. “The human condition is respected when [physicians] understand … [and] listen to the person’s story and respect … their wishes” one PC physician stated. Most PC physicians discussed the longitudinal and iterative nature of ACP discussions, with one stating that “patients can change their mind, their opinion, their decisions and they’re allowed to do it at any point in time even if it’s written in writing.” Both PC physicians and hospitalists identified physician-directed conversation as an essential aspect of ACP discussion with the SA population.

Identification of the patient’s representative/temporary substitute decision maker (TSDM) was commonly mentioned as a topic of discussion by both types of physicians; however, more hospitalists than PC physicians reported discussing concrete plans for care and legal/formal processes such as document completion, whereas more PC physicians reported raising patient awareness of the ACP process and the general need for it. Both physician groups informed patients of the consequences of delayed discussions, and both reported that discussion is often initiated too late and that “[delayed] communication becomes very difficult and time consuming.” They further stated that “[ACP conversation] should be done at the right time [and] when it’s too late, then things don’t work out” because delay causes a lack of knowledge of treatment or ACP options. The physicians also discussed the manipulation of language to increase ACP engagement with one PC physician stating “don’t… say [Dr is] putting [their] mom in a nursing home - that just doesn’t sound very good. It’s better to say, [the nursing home] provide[s] the support so she can have a better quality of life.”

Tool use

Two thirds of physicians reported using tools to facilitate ACP discussions, most commonly as templates and to help structure discussions. More physicians discussed the barriers to using ACP tools (n =17) than discussed the advantages of tool use (n = 11). ACP tools were reported as being advantageous as they offered a template to structure discussions with patients. One PC physician stated they “use the Serious Illness Conversation Guide and … base discussions off of [it] mostly … it’s always good to have a format but also to be flexible with the format.” When discussing barriers, some physicians reported that they “didn’t know [ACP tools] existed,” and their lack of knowledge about the available tools was a hurdle that prevented them from using ACP tools with their patients. With respect to feedback on the available tools, they discussed a need for culturally effective tools rather than the generic ones that exist today as “having … culturally effective and efficient tool is always better than generic tool” when engaging ethnic minorities. More PC physicians stated a preference for discussion over the use of tools as “from a culture perspective, [Dr.] think[s] [patient] desire[s] [to] talk about it rather than journaling.”

Physician evaluation of ACP discussion

Both types of physicians mentioned their negative and positive experiences when engaging in ACP with older SA adults and their families. The two most common influences on ACP discussion reported were practice context, specifically that they “wish they had more time to actually have a deeper conversation with [their] patients” and a lack of awareness/knowledge surrounding ACP because the “[patients] think that [Dr. is] bringing [ACP discussion] up because [Dr.] thinks [the patient is] dying.” Following these, framing, medical context and conditions, and physician–patient relationship were reported to influence the discussion. Both types of physicians reported on their backgrounds, including their competencies and specialties, as influencing ACP discussion. Notably, two thirds of PC physicians stated that ACP being a taboo topic for the SA population influenced discussion.

Physicians interviewed in 2020 and 2021 commented that “[ACP is] really a responsibility of family doctor.” One of the 2020 interviewees commented on the importance of the patient taking ownership.

Culture

As noted, a majority of the physicians were SA. Several spoke about the influences of religion/spiritual factors on ACP discussion, stating that “spiritual inclination or religious factors [were] playing behind their [ACP] decisions not just the poor health or the graph of the health going down.” One PC physician commented that “…[ACP] conversation is more challenging in South Asians…it isn’t talked about in the community…people might be offended…and interpreted like it’s a negative prognosis” and noted that “ACP is a sensitive topic [for SA] which is not brought up for discussion in regular visits.” Another noted that “the concept of ACP is not as common as [for the] ethnic minority community. So, oftentimes it can be the first time the subject has been broached.” PC physicians commented that family translators were an issue when engaging in ACP discussions with SA. The physicians identified the SA deflection of decision making onto physicians with one stating that the “[doctor] usually [is] able to tell [patients] what their code status should be and make them agree with it.”

Patient–physician cultural congruence

When asked explicitly about cultural congruence, just under two thirds reported it as an advantage because “people of South Asian descent … feel more comfortable speaking with someone who is of their cultural background and might understand the cultural significance of things a little bit more.” On the other hand, not all reflected this position, one stating “the cultural individuality is very varied in [SA] group[s], and it’s [important to acknowledge that] not all brown people have the same cultural background and …to dig deeper.” Another physician furthered this point by stating that “sometimes it’s better to bring someone from outside of the community [to do ACP].”

Family dynamics

Approximately two thirds of both types of physicians discussed the impact and perspectives of SA families. They most frequently discussed the effects of living arrangements/ support in the household and the family’s control over decision making as the “South Asian population … often will take care of their elders in their homes, and know their health very well, and are up to date on all their medical issues.” PC physicians noted that having SA family members working in health care was beneficial, as these “[family members] … see how important… [it] is to have a plan in [patient’s] record in case something was to happen.” Alternatively, some reported it as a disadvantage as the “[family members] know about all [the] different options for care, so they always ask for things that maybe, [the physician] don’t have ready access to, or they’ll know about … experimental treatments…so it’s harder.”

Approximately two thirds of the PC physicians and one third of hospitalists had experienced differences in the perspectives of family and patients concerning ACP, one noting that “sometimes the older person can be more open to the discussion…than the child.”

COVID-19

Only the interviews conducted in 2021 included questions about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their practice. Most PC physicians reported hybrid consults as their primary consultation method, followed by virtual and in-person consults. As one stated “medication refills or discussing [patients] blood reports and [continuing] their care… can be done on the phone easily." These physicians also discussed the advantages, which included the ability to “diagnose very serious problems on the phone … because [they] have more time, [they] relax [and] talk … at [their] own pace and have time to review files” and the disadvantages of telemedicine including “sometimes…on the phone you can miss the problems.” Although most commented that patients were fearful of contracting COVID-19 and of visiting hospitals, three PC physicians and one hospitalist noted that neither they nor their patients were afraid to see the other during the pandemic. About half of the physicians discussed changes in the number of visits and diagnoses, most commonly during operational hours; one physician stated that “primary care took a back seat for…practices… there’s going to be a wave of cancer because so much preventive surveillance was not done.” Half of the PC physicians reported that ACP discussion increased because of COVID, one stating the “[pandemic was] a reason to speak [of ACP] … in case [the patient] had got infected… it’s been kind of a way of opening up that type of discussion.” Most hospitalists reported that the frequency of ACP discussions was unaffected by COVID-19, because “the inpatient setting [the number of ACP discussions] has not changed because…the type of patients we’re seeing are pretty sick and need a lot of ACP discussions in hospital.” They further identified a need for the “government/ministry to…recognize and support [them] and the infrastructure that [they] are using…because…the [MSP billing] funds doesn’t always cover the cost of business."

Ethnic comparisons

Both types of physicians compared SA acceptance and the likelihood of engaging in ACP to that of other ethno-cultural groups. Approximately half of the physicians stated that the white population is more accepting, aware, and engaged with ACP, and that people of colour are less likely to initiate ACP discussion, as “White Europeans are much more aware of [ACP] than brown South Asians.” Less commonly, they reported no difference in ACP discussion across cultural groups. Compared with PC physicians, more hospitalists reported that whites are more likely to have made an ACP plan or to have communicated their wishes, and that the SA population is less accepting, aware, and engaged with ACP than other groups. More hospitalists also compared the difference in physician and patient/family perspectives. Both types of physicians indicated that ethnic families have greater involvement in patients’ health care than whites, as “the…matriarch/patriarch are so important in the family, that…not doing everything even if it’s futile [is a] challenging decision for South Asian families,” and that family dependency and children dominating the patient’s rights are barriers to ACP discussions. Furthermore, both types of physicians stated that there are more communication barriers in the Chinese population than among SA.

2020 Interviews versus 2021 Interviews

Two differences were seen between the interviews conducted in 2020 and those conducted in 2021. First, 2021 physicians reported utilizing other colleagues as a resource to have ACP discussions, which may be the result of increased reliance on teamwork as the pandemic progressed. This inference is further supported, as one of the physicians stated that their team had one “physician … who was fully gowned and had PPE on … [and they] examined the patient … if needed.” Additionally, a much greater number of the physicians interviewed in 2021 discussed cultural congruence. This was mainly because they were directly asked about the advantages and disadvantages of working with a population with the same ethno-cultural background as theirs.

Suggestions

Both types of physicians suggested that “[ACP discussion] just has to become more routine … [so that] it becomes so commonplace that everybody just expects it.” It was also suggested to put the onus on PC physicians and utilize social workers when conducting ACP discussions. The physicians also suggested partnering with third-party organizations, like “their [patient’s] religious organizations,” to increase ACP in the SA population.

Discussion

This study explored PC physicians and hospitalists’ experience with ACP discussion with SA older adults, one of Canada’s largest minorities, difference in physicians’ training and use of tools, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on ACP facilitation. Key findings from our analysis are discussed in the following sections.

Role of Physicians in ACP Discussion

Physicians from this study reported that they often take on the role of educating patients about their rights and decision-making process and are incumbered with initiating and introducing ACP discussion. These findings are consistent with Bernard et al.’s (Reference Bernard, Tan, Slaven, Elston, Heyland and Howard2020) findings that patients from the general population do not initiate ACP discussions and expect the physician to initiate them. They may be reluctant to initiate discussion out of fear of disagreement about ACP and its negative impact on their patient–physician relationship or fear that if their values and beliefs do not align with the physician’s, they may be forced into treatment that does not align with their wishes. Biondo et al. (Reference Biondo, Kalia, Khan, Asghar, Banerjee and Boulton2017) note that SA may have overconfidence in their physician’s abilities and feel that physicians would better know when and how to start these discussions. In our study, one physician reported adopting a paternalistic approach to better reach SA patients.

Yarnell et al. (Reference Yarnell, Fu, Bonares, Nayfeh and Fowler2020) note that more SAs than individuals from the general population die in the intensive care unit (ICU). They suggest that these differences may be the result of difficulty in patient–clinician communication and reduced access to palliative care services or other end-of-life options. Our findings support their contention with respect to difficulty in patient–clinician communication. They also support the suggestion by Sharma, Khosla, Tulsky, and Carrese (Reference Sharma, Khosla, Tulsky and Carrese2012) that physicians determine with whom the patient feels most comfortable, communicating the patient’s preferred care plan and facilitating conversation between the two.

Samanta (Reference Samanta2013) determined that physicians’ personal beliefs hold significant power in influencing ethnic minorities’ willingness to engage in, and beliefs surrounding ACP discussions, causing them to reflect the physician’s values instead of forming their own. Physicians may need to mask their faith and beliefs during ACP discussions to avoid influencing the patient’s decisions and reduce discrimination when caring for the patient. However, physicians in our study reported using this dynamic by manipulating the framing in which ACP was introduced to produce favourable reception. In particular, almost a third of those interviewed reported manipulating language to increase ACP engagement with SA older adults.

PC Physicians versus Hospitalists as Initiators of ACP

Both PC physicians and hospitalists spoke to the form and content of ACP discussion, emphasizing PC practice’s longitudinal and iterative nature. Patients more frequently visit PC physicians, allowing them to form relationships and revisit topics multiple times. When hospitalists engage in ACP discussion, it is a time-sensitive discussion; therefore, they must focus on imminent decision making rather than on increasing patient ACP awareness. Therefore, PC physicians were viewed to hold the ideal position to introduce ACP.

Cultural Congruence

Physicians reported that cultural congruence served as an advantage when engaging in ACP discussion with older SA adults. This may be because a culturally congruent physician is more receptive to their patient’s values and knows how to initiate ACP topics with cultural and religious sensitivity, to optimize effective engagement (Samanta, Reference Samanta2013). Previous research (Periyakoil et al., Reference Periyakoil, Neri and Kraemer2016) has determined that physicians with the same ethnicity as their patients report decreased barriers in conducting ACP discussions compared with physicians engaging with ethnicities different from their own. However, Samanta (Reference Samanta2013) notes that health care providers with a strong faith in their religious teachings have a reduced probability of discussing end-of-life care options associated with death. In our study, one third of physicians reported cultural congruence as being either neutral or a disadvantage.

Barriers to ACP

Similar to the findings of Fulmer et al. (Reference Fulmer, Escobedo, Berman, Koren, Hernández and Hult2018), physicians in this study reported a lack of time as a main barrier to engaging in ACP discussion with their patients. Previous studies reported language and medical interpretation, religious/spiritual beliefs, physicians’ ignorance of patients’ cultural beliefs and values, patients’ limited health literacy, and patients’ mistrust of physicians and the health care system as the most commonly experienced barriers to ACP engagement (Periyakoil, Neri, & Kraemer, Reference Periyakoil, Neri and Kraemer2015). Consistent with their findings, physicians in this study reported that cultural and communication barriers are common.

Similarly to Kwak and Haley (Reference Kwak and Haley2005) and Menon et al. (Reference Menon, Kars, Malhotra, Campbell and van Delden2018), our physicians reported that SA older adults lacked awareness of ACP and were less likely to engage in ACP discussion than whites as “the concept of ACP is not as common” amongst the SA population; “White Europeans are much more aware of [ACP] than brown SAs.” Additionally, physicians reported that SA older adults have an increased tendency to deflect their decision making onto physicians. This coincides with Menon et al.’s (Reference Menon, Kars, Malhotra, Campbell and van Delden2018) results, which found that SAs deflect decision making onto physicians. However, they reported that SA older adults are less engaged and accepting of ACP discussions, primarily because of cultural and religious norms. Only a few of our physicians attributed the reluctance to engage in ACP to these factors. Furthermore, it was suggested by one of our physicians that SA’s transfer of decision-making power to physicians is not out of fear or trust but rather is a default decision because of the community’s lack of knowledge about ACP.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

One of the unique facets of this study was investigating how physicians serving ethnic minorities and their patients adapted to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of new forms of ACP delivery that this necessitated. Virtual appointments became an integral practice in many PC physicians’ offices, as they mitigated risk of exposure and fears about the COVID-19 virus. Most of the PC physicians interviewed reported engaging in some sort of hybrid model of appointments, as most consults could be conducted virtually. Telemedicine, in particular, proved popular as it gave physicians more access and insight into patients’ family dynamics and significant influencers. It also allowed them an increased amount of time with patients something that is not possible during in-person consults. However, others noted that virtual consults using Zoom were difficult to conduct with older patients who lacked technological literacy.

Furthermore, the Ministry of Health’s lack of compensation and infrastructure further exacerbated the physicians’ communication challenges, as they only had so much time and energy to deal with such non-medical issues. At such a time of unprecedented obstacles, physicians stressed the need for support and infrastructure from the Ministry of Health, which essentially left physicians to develop a technological understanding independently. As a result, some physicians expressed concerns that PC took a back seat, with preventative surveillance declining.

Whereas Jones (Reference Jones2021) found that the pandemic triggered end-of-life discussion, most physicians in this study reported no change in engagement and acceptance of ACP discussion. One notable reason was that these discussions had been infrequently conducted before the pandemic, and physicians had even less time to conduct them during the pandemic. Furthermore, in the hospital setting, the occurrence of ACP discussions did not change during the pandemic because the level of patient illness severity did not change and therefore, there was no change in the frequency of ACP discussions. Overall, COVID-19 was a catalyst for physicians to adopt and implement more virtual consultation systems (i.e., telemedicine), making medical consultations “more accessible” and beneficial if physicians knew their patients well. However, it had little impact on increasing engagement in ACP.

Study Challenges/ Limitations

The most significant challenge to conducting this study lies in the recruitment phase. Physicians were reluctant to participate, citing their busy schedules and being wary of having their concerns documented. This reluctance was further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited our interviews to being conducted virtually only. However, no significant differences in the data were seen among those interviews conducted in person, online, or over the phone.

Conclusion

Key implications of the study are that ACP discussions should be engaged in regularly by more PC physicians, and perhaps especially by those who work with the SA population given its lack of familiarity with the concept. Half of the participants had little to no experience engaging in ACP discussion with their SA patients. Because physicians and patients expect PC physicians to initiate the discussion, those who work with the SA population should be formally trained in ACP, including how best to raise the topic and navigate such discussions. Although most of our interviewees see cultural congruence as an asset, not all agree. Where all do agree is that all physicians serving the SA population (and, by extension, those serving other cultural minorities) should strive to understand and consider the patient’s culture. We speculate that although COVID-19 was a catalyst for physicians to adopt and implement more virtual consultation systems (i.e., telemedicine), making medical consultations “more accessible,” the pandemic had little impact on increasing engagement in ACP.

Funding

This study is part of a larger project (iCAN-ACP) funded by a grant from the Canadian Frailty Network (formerly Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network), which is supported by the Government of Canada through the Networks of Centres of Excellence (NCE) program.