Introduction

As we enter the era of the fourth industrial revolution, there are great concerns about jobless growth. For this reason, interests in the new income security policy is on the rise. This may be why there has recently been a lot of debate about basic income around the world. Even founders of high-tech companies like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg are calling for a basic income in the case of a jobless world. The onset of the Covid-19 pandemic adds to interests in the basic income (Nettle et al., Reference Nettle, Johnson, Johnson and Saxe2021). Andrew Yang in the 2020 US presidential election and Lee Jae Myung, the ruling party’s presidential candidate in the 2022 Korean presidential election, has made a basic income as one of their major electoral pledges.

Various basic income experiments are underway. In Finland, although limited to the long-term unemployed, the central government conducted an experiment in which basic income was paid out in lieu of unemployment benefits. In addition, many basic income experiments at the local government level and in the private sector are taking place in developed countries such as the United States, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, and Spain, as well as developing countries such as Kenya, Namibia, and India (Karakas, Reference Karakas2016; Samuel, Reference Samuel2020).

Yet in Sweden, as Zamboni points out, “the idea of introducing a basic income scheme, either in its full form or a partial version, is rather absent from the political and legal agenda of the Swedish legislator….the very thought of introducing such reform into the political debate is considered political suicide” (Le Moine Reference Le Moine2019; Zamboni, Reference Zamboni2021: 343). Zamboni may somewhat exaggerate the current state of silent talks over basic income in Sweden. Nevertheless, it seems clear that all of the parliamentary parties in Sweden dismiss the idea of basic income as unrealistic and ineffective except the Green Party (Birnbaum, Reference Birnbaum2013). Moreover, Swedish people generally do not support basic income and have a negative perception (Ekstrand, Reference Ekstrand and Borg2013; Müller, Reference Müller2013; Wetterstrand, Reference Wetterstrand2017; Lee, Reference Lee2018).

According to the results of the European Social Survey (ESS) conducted in 2016, only 37.6 per cent of Swedish citizens supported basic income while 62.4 per cent opposed it. Swedish people’s opposition to basic income is second only to Norway and Switzerland in Europe (Fitzgerald, Reference Fitzgerald2017). As Müller argues, the Swedish welfare model characterised by high decommodification, universal solidarity, and strong social relationship seem to be a key factors that would make a meaningful effect on the Swedish people’s averse perception of the universal basic income (Müller, Reference Müller2013).

On the other hand, in South Korea, discussions over basic income are relatively active in academia and in politics as well. Even an ardent advocate of universal basic income (UBI), Lee Jae Myung had gained popularity by introducing a youth basic income to Seongnam City, paving the way to the governor of Gyeonggi Province, the largest regional government in Korea. He finally made a UBI for all citizens as one of his presidential electoral pledges of the ruling party in 2022. In fact, most opinion poll results show that Koreans are more supportive for a UBI than against (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yun and Jang2021).

Why are the people’s attitudes towards basic income so different and the degree of discussion as a policy alternative also different? We believe that an individual-level survey of people’s attitude in a representative small welfare state, South Korea, and an exemplary big welfare state, Sweden, would give us a clue to identify the cause of contrasting attitudes towards basic income (Yang, Reference Yang2017). Korea could be dubbed as a small welfare state in that social welfare programmes have been introduced belatedly, coverage is limited, and benefits are modest. In 2021, Korea’s public social expenditure is 14.9 per cent of the gross domestic product (GDP) while that of Sweden is 24.9 per cent. In terms of tax burden, Korea is a small government. In 2021, Korea’s tax revenue as percentage of GDP is 29.9 whereas that of Sweden is as high as 42.6. In this most different system design, we could effectively confirm common determinants of attitudes for or against the basic income (Lijphart, Reference Lijphart1971). Also, key features differentiating the Korean small welfare state from the Swedish big welfare state, such as levels of social security and tax burden, could be identified as factors behind people’s different attitudes towards UBI. In order to figure out differences within similarities we conducted surveys in Sweden and Korea with the same questionnaire in 2020 and 2021.

Several cross-national studies on people’s attitudes towards basic income have analysed and tested both individual-level socioeconomic factors and country-level differences. Focusing on European countries, these studies have discovered that variations in people’s attitudes towards basic income across nations can be attributed to differences in national-level welfare benefits. Across European countries, individuals who currently benefit from generous national welfare provisions or express satisfaction with existing welfare policies tend to hold unfavourable attitudes towards basic income. Conversely, those facing limited national welfare benefits or expressing discontent with existing welfare policies, particularly in relation to reducing poverty and income inequality, tend to exhibit more favourable attitudes towards basic income (Lee, Reference Lee2018; Parolin and Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020; Roosma and Van Oorschot. Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2021; Choi, Reference Choi2021; Busemeyer and Sahm, Reference Busemeyer and Sahm2022; Laenen and Gugushvili, Reference Laenen and Gugushvili2023).

This study builds upon prior research by contributing to the existing body of knowledge in several distinct ways. Firstly, through a comparison of Sweden and South Korea, this study expands its scope beyond European countries to comprehend people’s attitudes towards basic income. Secondly, in contrast to existing literature, which predominantly explored attitudes towards basic income alone (Lee, Reference Lee2018; Parolin and Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020; Roosma and Van Oorschot. Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2021; Choi, Reference Choi2021; Busemeyer and Sahm, Reference Busemeyer and Sahm2022), this study introduces a nuanced approach by distinguishing between attitudes towards basic income and attitudes towards the necessary tax increases for funding. Thirdly, this study includes a variable for perceived tax burden, often overlooked in prior research, to elucidate the contrasting attitudes towards both basic income and the associated tax increases in Sweden and South Korea.

Furthermore, previous comparative studies, which predominantly focused on European countries, either analysed the correlation between individual-level support for basic income and country-level differences in social spending using multilevel analysis or explained attitudes towards basic income based on satisfaction with national welfare provisions (Parolin and Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020; Roosma and Van Oorschot. Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2021; Busemeyer and Sahm, Reference Busemeyer and Sahm2022). In contrast, by comparing two divergent welfare states, Sweden and South Korea, this study explores how tax burdens and the preparedness for social risks, shaped by their respective national welfare systems, directly influence individuals’ attitudes towards basic income and related tax increases at the individual level.

What is basic income and who support it?

Definition and argument for and against basic income

According to a definition by the BIEN (Basic Income Earth Network), which is an international centre of UBI movement, a basic income is a periodic cash payment unconditionally delivered to all on an individual basis, without means-test or work requirement. The basic income has five characteristics (BIEN, 2022). First, it is paid on an individual basis – and not, for instance, to households. Second, it is paid in cash, allowing those who receive it to decide what they spend it on. It is not, therefore, paid either in kind (such as food or services) or in vouchers dedicated to a specific use. Third, it is paid at regular intervals (for example, every month), not as a one-off grant. Fourth, it is paid without a requirement for work-age people to work or demonstrate a willingness to work. Five, it is paid to all, with neither means-test nor needs-test.

Currently, no country has implemented a UBI with all of the five elements mentioned by BIEN. The recipients of basic income experiment in Finland were the long-term unemployed, not the entire nation. Alaska’s oil dividend is not a monthly payment, only paid once a year. The Youth Basic Income of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea, is a one-year programme, limiting beneficiaries to those who turns twenty-four years old only. In addition, it is paid out in a local currency usable only in Gyeonggi Province.

Nevertheless, all of these are called basic income. It is because, as Philippe Van Parijs eloquently points out, what constitute the basic income is ‘unconditional[ity] in a strong interpretation of this adjective’ (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2017: 8). In other words, it should be called a basic income if distributed unconditionally regardless of income, assets, capability of work, and above all whether or not there is demonstrable and abject needs (Janson, Reference Janson2003).

In some cases, cash benefits of the existing social security system are paid unconditionally. This is the case with demogrants, such as tax-based basic pension and child allowance. But it is not called basic income because it is paid to a certain demographic group only who are deemed incapable of work. Under the current social security system, there is no unconditional income transfer to working-age population regardless of social risks or needs. Cash benefits are usually paid on a condition of training or willingness to participate in the labor market. Also, the amount of social welfare benefits is not the same unlike basic income. Adequacy is the norm. High-income earners receive relatively higher social insurance benefits than low-income earners. On the contrary, those under the poverty line receive more public assistance than those above the line. However, UBI does not give such consideration to people in need (Yang, Reference Yang2020).

Basic income is often justified as a way to strengthen social security. But also highlighted are (i) baseline for freedom, (ii) the advent of a jobless society due to the spread of robots and artificial intelligence, (iii) the increase in atypical work such as platform labor, and (iv) citizens’ right to the commonwealth such as land and underground resources (Van der Veen and Van Parijs, Reference Van der Veen and Van Parijs1986; Standing, Reference Standing2011; Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2017, Geum, Reference Geum2020: 186).

The logic against basic income is also clear (Minogue, Reference Minogue2018; Yang, Reference Yang2020; Chui et al., Reference Chui, Manyika and Miremadi2015). First, as equally splitting available resources indiscriminately, basic income could neither be large enough to provide income protection nor to promote freedom of those in need. Second, jobs are not disappearing; they are changing. It is necessary to use available resources to develop vocational skills in advance rather than spending money inefficiently on ex post cash payments. Third, it is more desirable to use the profits generated by the commonwealth according to national priorities rather than equally splitting into dividends.

Attitudes towards basic income and related tax increases

To understand individuals’ attitudes towards basic income, existing empirical studies have often examined the effects of economic interests, personal values, and ideological inclinations at the individual level (Parolin and Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020; Roosma and Van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2021; Choi, Reference Choi2021). Regarding economic interests, according to Meltzer-Richard’s model (Meltzer and Richard, Reference Meltzer and Richard1981), people with high incomes and stable positions in the labor market are likely to pay more taxes than the amount of basic income they would receive. Thus, they would be unfavourable to basic income. The more progressive the tax structure, the greater this tendency would be. On the other hand, the low-income class with unstable employment in the labor market pay less tax than they would receive from basic income. Therefore, the low-income class is expected to show a more favourable attitude towards basic income (Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2021; Lasen, Reference Larsen2008). Personal values and ideological inclinations matter as well. Political leftists, or people with progressive ideologies, are more likely to show a favourable attitude towards basic income and related tax increases since they favour redistribution and equality over achievement and freedom (Edlund, Reference Edlund2003; Svallfors, Reference Svallfors2011; Fernández-Albertos and Kuo, Reference Fernández-Albertos and Kuo2018).

In addition to economic interests and ideological factors, this study explores how individuals’ perceptions of the social security system and tax burden contribute to varying attitudes towards basic income and associated tax increases in the contexts of Sweden and South Korea. Previous research examined the influence of country-level social spending on individuals’ attitudes towards basic income, revealing that those in countries with higher social spending tend to hold less favourable views of a new income transfer system like basic income (Müller Reference Müller2013; Lee, Reference Lee2018; Parolin and Siöland, Reference Parolin and Siöland2020; Roosma and Van Oorschot, Reference Roosma and van Oorschot2020; Vlandas, Reference Vlandas2021; Busemeyer and Sahm, Reference Busemeyer and Sahm2022). In contrast, this study investigates the impact of individual-level preparedness for income loss on attitudes towards basic income, shifting the focus from country-level social spending. Differences in preparedness for income loss between Sweden and South Korea, arising from disparities in their income security systems, are expected to elucidate the contrasting attitudes towards basic income in these two countries. It is worth noting that the existing income security system may influence citizens’ attitudes towards basic income. The more people believe that the existing social security system functions effectively and thus feel protected against income loss, the less favourable their attitude will be towards basic income.

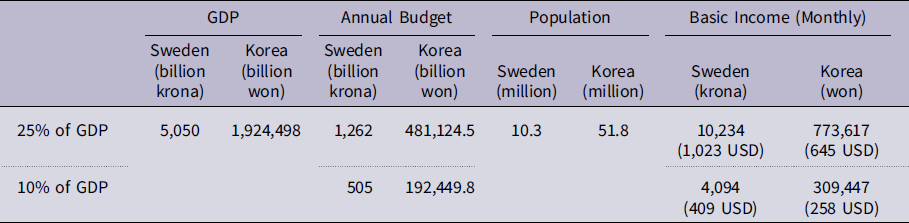

People who perceive that they bear a heavy tax burden are also likely to hold negative attitudes towards basic income. Since basic income is an unconditional payment of regular cash benefits to all citizens, it requires huge financial resources. For example, Van Parijs proposed a start of UBI with 10 per cent of GDP and gradually increase the payment up to 25 per cent of GDP (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2017: 11). As shown in Table 1, at 25 per cent of GDP, Sweden would have a basic income of 1,0234 kroner per month (about 1,023 the United States dollar (USD) as of 2019). To achieve this, the total tax burden should be raised from the current 42.8 per cent to 67.8 per cent of GDP. In Korea, the total tax burden should be raised from current level of 28 per cent of GDP to 38 per cent and 53 per cent, respectively. All of the projections exceed the average total tax burden of OECD countries: 33 per cent of GDP. Even if some existing cash programmes are to be replaced with basic income, the cost would still be enormous.

Table 1. Amount of basic income and required budget

Note: year 2019; 1,200 won = 1 USD; 10 krona = 1 USD.

Source: OECD Statistics, 2022.

UBI proponents argue that basic income would not have as much tax resistance as the tax increases for social welfare (Kang, Reference Kang2019). Unlike social welfare benefits, everybody receives basic income regularly. You can easily calculate the difference between the tax money you pay and the basic income you receive. Therefore, the majority of citizens know that the basic income they receive is higher than the additional taxes they pay (Francese and Prady, Reference Francese and Prady2018). This is why UBI proponents expect more people to support tax increases for basic income than in the case of social welfare. In addition, by levying a tax on the commonwealth such as land and data, and discovering new alternative tax sources such as a robot tax or a carbon tax, it would be possible to minimise the increase in income tax to which people are most resistant (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2017).

However, even though raising taxes for basic income may be relatively easier than social welfare, as prospect theory predicts, humans tend to be more sensitive to losses than gains (i.e., loss aversion) (Kahneman and Tversky, Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979). No matter how beneficial the basic income is, there is a high possibility that they would take a negative attitude towards the tax increases, by which money is immediately took out of one’s pocket. And even those who acknowledge the need for tax increases for the introduction of basic income would try to avoid their own tax burden as much as possible. They would prefer to raise taxes on the rich and corporations rather than themselves. In short, so-called NOOMP (Not Out Of My Pocket) phenomenon is expected (Yang et al., Reference Yang, Yun and Jang2021).

What kind of attitudes will Swedish and Koreans have towards basic income and allied tax increases? We will look at the results in the next section.

Survey results

Data and variables

We utilised the results of two nationwide surveys carried out in South Korea and Sweden. Using same questionnaires, Research and Research of South Korea and Norstat of Sweden, which are public opinion polling companies, surveyed opinions on UBI and related tax increases in 2020 and 2021, respectively. A proportionate quota-sampling procedure was used to gather a representative sample of those aged eighteen years or over across gender, age, and region. The number of total observations (N) are 2,502 and 2,027, respectively. The survey data of Sweden are weighted using random iterative method (RIM) weighting to adjust sample proportions to reflect population proportions for gender, age, and regions.

Dependent variables are attitudes towards basic income and related tax increases. Attitudes towards basic income are measured by asking respondents to how much they favour or oppose the introduction of UBI.Footnote 1 Attitudes towards tax increases for basic income are measured with a question that asks respondents whether they will agree or disagree if the introduction of basic income means tax increases. For dependent variables, the scale of measurements goes from one (strongly disagree) to four or five (strongly agree).

To account for attitudes towards UBI and allied tax increases, this study assesses four independent variables, which are household income, political ideology, preparedness for social risks, and perceived tax burden. The measure of household income is an ordinal scale variable. Household income is classified into twelve groups with intervals of 1,000 won in South Korea and 20,000 kronor in Sweden. Political ideology is measured by asking respondents to indicate where they would place their ideological views on a five-point scale ranging from ‘far right (1)’ to ‘far left (5)’. Preparedness for income loss is assessed by asking respondents how much prepared they are for income loss due to illness, unemployment, and retirement. The responses scale ranges from ‘not at all prepared (1)’ to ‘very prepared (5)’. Perceived tax burden is measured on a five-point scale, indicating whether respondents’ tax burden is ‘very low (1)’ to ‘very high (5)’.Footnote 2

This study includes a set of control variables to control for other potential effects, which are related with attitudes towards basic income and related tax increases. Gender is coded 0 for female and 1 for male. Age is a continuous variable measured by year of birth. The survey asks respondents to indicate their marital status with three options (1 = single, 2 = married and living together, and 3 = married but not living together because of divorce or separation, etc). Marital status is re-coded with a binary variable to differentiate individuals who are currently married and living together (1) from others (0). Education is measured on a six-point scale from elementary education (1) to postgraduate education (6). Employment is a dichotomous variable that equals 0 if the respondent is without a job and 1 if the respondent is working.

Descriptive statistics: contrasting people’s attitudes

Figure 1 presents a comparison of attitudes towards the introduction of basic income in Sweden and South Korea. Ample variation in support for basic income is observed between the two countries. In Sweden, only 17 per cent of respondents agree with the introduction of basic income (strongly agree = 4.3 per cent and agree = 12.7 per cent), but 45.7 per cent of them disagree with it (21 per cent = strongly disagree and 24.7 per cent = disagree). Korean respondents show different preferences for UBI. In South Korea, there are much more respondents who favour basic income than those who are against it; 42.9 per cent of respondents agree with the introduction of UBI (strongly agree = 9.7 per cent and agree = 33.2 per cent), while only 26 per cent of them disagree with it (strongly disagree = 10 per cent and disagree =16 per cent).

Figure 1. Attitudes towards basic income in South Korea and Sweden (per cent).

Figure 2 depicts a variation in attitudes towards tax increases for basic income in Sweden and South Korea. There is a clear difference in attitude between Sweden and Koreans towards a basic income-related tax increase. In Sweden, few respondents (27.2 per cent) are supportive for tax increases for basic income (strongly agree = 2.3 per cent and agree = 24.9 per cent), and the largest share of respondents (72.8 per cent) are against tax increases (strongly disagree = 35.2 per cent and disagree = 37.6 per cent). On the one hand, in South Korea, more than half of respondents (54.8 per cent) agree with tax increase to introduce basic income (strongly agree = 6 per cent and agree = 48.8 per cent), while 45.1 per cent of them do not want to raise their taxes (strongly disagree = 14.6 per cent and disagree = 30.5 per cent).

Figure 2. Attitudes towards tax increases for basic income in South Korea and Sweden (per cent).

Why are Swedish respondents less receptive to the introduction of basic income and tax increases to pay for it than South Korean respondents? According to Supplementary Table 1 in the Appendix, the distribution of survey respondents by variable was by and large similar across both Sweden and South Korea, but household incomes and preparedness for income loss varied. As for household income, more Swedish respondents were placed in the low-income bracket than the Korean. Another larger difference was seen at the social security level. As shown in Table 2, 69.2 per cent of Swedish people responded that they were prepared for income loss like unemployment, while only 19.8 per cent of Korean respondents answered that they were protected against income loss.

Table 2. Household income and preparedness for income loss in Sweden and South Korea

Note: Monetary unit of household income: Sweden (kronor), South Korea (1,000 won).

The fact that more Swedish respondents are distributed in the low-income brackets than Koreans may likely to increase the proportion of positive respondents for basic income in Sweden. On the other hand, a higher number of respondents in Sweden who believe they are already well-prepared for an income loss leads them to less support for basic income than in Korea. Which variable would be more critical in determining people’s attitude on UBI? In the lowest income stratum, 45 per cent of Swedish respondents indicated they are prepared for income loss, as opposed to only 8.2 per cent of Korean respondents. In the second lowest income stratum, as much as 69.8 per cent of Swedish respondents are prepared to lose income, while 15.5 per cent of Korean respondents are prepared. It strongly suggests that social security is a decisive variable that makes the difference between Swedish and Korean people’s contrasting attitude on basic income.

Meanwhile, the perceived tax burden among Swedish and Korean people also varies. As shown in Table 3, the overall percentage of respondents who consider the tax burden to be high is quite similar in Sweden and South Korea, standing at 47.2 per cent and 47.5 per cent, respectively. However, the disparities in the perceived tax burden become evident when examining income strata across the two nations. In Sweden, respondents across all income strata tend to think the tax burden as high, with even the lowest income group having 49.1 per cent of respondents perceiving it as such. In contrast, South Korea displays a distinct pattern, where the percentage of individuals perceiving a high tax burden increases with higher income levels. In the lowest income stratum, only 34.6 per cent consider the tax burden to be high, but this percentage gradually rises with income levels, reaching 52.1 per cent. Consequently, in South Korea, individuals with lower incomes, coupled with a lower perceived tax burden, are more inclined to support basic income and agree with tax increases to fund it. On the other hand, in Sweden, the perception of a high tax burden remains consistent across income levels, implying that even lower-income groups may exhibit less enthusiasm about basic income and the associated tax increase.

Table 3. Household income and perceived tax burden in Sweden and South Korea

Note: monetary unit of household income: Sweden (kronor), South Korea (1,000 won).

Regression results: common factors deciding people’s attitudes

Since the dependent variables are ordinal, this study uses an ordered logistic regression model to assess people’s attitudes towards basic income and related tax increases. Figure 3 visualises the key findings of the ordered logistic regression model, in which we analyse the relationship among four independent variables and attitudes towards the introduction of basic income across Sweden and South Korea, controlling for control variables.Footnote 3 As theoretically expected, all four independent variables exhibit statistically significant relationships with attitudes towards the introduction of basic income. However, the substantive sizes of their relationships differ somewhat between the two countries.

Figure 3. Attitudes towards the introduction of basic income.

Note: average marginal effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals of four independent variables in an ordered logistic regression; control variables: gender, age, marital status, education, and employment. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

This study expects the high-income class to possess unfavourable attitudes towards basic income. We find support for this expectation. The coefficients of household income are negative and statistically significant for both Sweden and South Korea. However, household income has stronger negative effects in Sweden than in South Korea. The higher the income level, the more negative the attitudes are towards basic income in Sweden than in South Korea.

As expected, political ideology is positively and significantly related to attitudes towards basic income. Political leftists are more likely to favour the introduction of basic income in both countries; however, the effect of leftist political ideology advocating basic income is stronger in Sweden than in South Korea.

We observe that preparedness for income loss is negatively and significantly related to attitudes towards basic income in both Sweden and South Korea. However, the negative relationship is much stronger in Sweden than in Korea. This finding shows that, compared to Koreans, Swedish people tend to be far less supportive of basic income as they know that they are well prepared for an income loss because their social security system provides seamless income security during periods of illness, unemployment, or retirement.

Perceived tax burden is negatively and significantly related to attitudes towards basic income in both countries. As expected, people who feel burdened by taxes are more likely to oppose basic income, but the negative effect of perceived tax burden is a bit more prominent in South Korea than in Sweden.

Figure 4 presents the effects of four independent variables on attitudes towards tax increases for basic income in graphical form.Footnote 4 As theoretically expected, the level of household income is negatively related to attitudes towards tax increases, but the relationship is not statistically significant in both countries.

Figure 4. Attitudes towards tax increases for basic income.

Note: average marginal effects with 95 per cent confidence intervals of four independent variables in an ordered logistic regression; control variables: gender, age, marital status, education, and employment. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

Political ideology supports our expectations. In South Korea and Sweden, more people with leftist political ideology favour raising taxes for basic income. In Sweden, leftist ideology influences attitudes a bit more strongly than in South Korea towards tax increases for basic income.

As we expected, preparedness for income loss is negatively and significantly related to basic income tax increases in Sweden. It is more likely that people who believe they have already prepared for social risks will disapprove of tax increases. However, preparedness for income loss does not significantly affect attitudes towards tax increases for basic income in South Korea, while its relationship with attitudes towards the introduction of basic income is statistically significant in Fig. 3.

Finally, as we expected, as people perceive their tax burden to be high, their attitudes towards tax increases for basic income turn negative. The negative effect is stronger in Sweden than in South Korea. Perceived tax burden causes Swedish people to be more strongly opposed to tax increases for basic income than Korean people.

Discussions

Our survey results affirmed the contrasting attitudes of Swedish and Korean people regarding basic income. Koreans are relatively supportive of basic income and related tax increases while Swedes showed the opposite. Yet, the analysis of ordered logistic regression models revealed similarities within the difference as well. Those with high income, political right orientation, high protection against income loss, and high tax burden would be more unfavourable towards introduction of basic income no matter which country they live in. Regarding a tax raise for basic income, peoples in the two countries showed similar patterns except preparedness for income loss due to unemployment, retirement, and etc. Income security proved not statistically significant in South Korea.

Along with high tax burden, Sweden’s income security system is one of the most developed in the world in terms of comprehensiveness and benefit levels, whereas Korea’s income security system is not yet fully developed. Unlike Swedes, most Koreans are either weakly protected by income security or have no protection at all. Indeed, only 19.8 per cent of respondents in South Korea, which is a third of Sweden’s, think that they are protected from loss of income. Those who feel under-prepared for income loss by existing social security system would be tempted to alternative income protection measures like basic income. Policy makers often have to devise makeshifts to make up for the lack of infrastructure for income security during economic crisis while politicians often use that niche to mobilise political supports.

In the midst of the economic crisis caused by the Covid-19, the emergency income security measures taken by the Korean government were different from those of Sweden. While Sweden responded to the loss of income by temporary changes within existing income security system rather than new measures, the Korean government chose to provide basic income-type emergency disaster allowances (hereafter EDA).

In Sweden, both tiers of unemployment benefit (i.e. contribution-based earning-related benefit and tax-based basic benefits) were raised in value, waiting days abolished, and eligibility criteria relaxed for all unemployed people including the self-employed, part timers, and gig workers. The ‘five-year rule’, under which the self-employed are banned from the programme for five years after the receipt of benefits to reduce excessive use or fraud, was abolished in 2020 to protect the self-employed hit by social distancing. Employers could receive job retention benefits not only for regular workers but also for part-time and temporary contracts. Sick pay deduction was also removed to support all people with symptoms, including the self-employed and irregular workers. Temporary parental benefits for sick children were expanded to cover healthy children who enrolled in schools that were closed due to the pandemic. Families with children automatically got an extra housing allowances up by 25 per cent of the regular payment (Fritzell et al., Reference Fritzell, Nelson, Heap and Palme2021).

But in South Korea, there were no tax-based unemployment assistance, no sickness allowance, no parental leaves for sick children, and no housing allowance. Although unemployment insurance provides unemployment benefits to the unemployed and job retention benefits to employers, it covers about 50 per cent of workers only. The self-employed, part-time, and temporary workers, who were hit hardest by the Covid-19 economic crisis, had little support to rely on. Previously the Korean government widely used public works to provide jobs and income support to the vulnerable whenever mass unemployment occurred during economic crises (Yang, Reference Yang2017). However, public works were a risky alternative to choose during the pandemic, which required social distancing. Accordingly, EDA similar to the basic income was provided five times. Disaster allowances were provided to households below the median income three times, regardless of whether income was reduced or damaged due to the pandemic. In the other two times, the allowance was distributed to 100 per cent of all citizens in May 2020 and to all households except for the top 10 per cent in July 2021 (Jung et al., Reference Jung, Lee and Yun2021).

There was a big debate over whether to provide EDA to nearly all citizens indiscriminately or to provide more targeted support to the people in need. However, ahead of the 2020 general election and the 2022 presidential election, the then-ruling party made a political choice to respond to the Covid-19 economic crisis through a policy of paying more voters in cash. Moreover, the ruling party presidential candidate, Lee Jae Myung, promised universal basic income as one of his top electoral pledges. Although Lee lost to the opposition party candidate who insisted on more targeted support, it showed that an idea of basic income could appeal to the people in South Korea where social security is weak and tax burden is low.

In Korea, about 40 per cent of income earners are exempt from income tax.Footnote 5 Moreover, the income tax rate for the lowest bracket is mere 6 per cent. This is in stark contrast to Sweden, in which most people pay local tax on their income as high as 28.98 per cent to 35.15 per cent. This may be why lower-income Koreans seem to be less opposed to a basic income tax increase than Swedes, while Swedes, regardless of income level, are strongly opposed to a tax increase for basic income. All in all, there is little room for the introduction of basic income in Sweden, which has a highly developed income security system for all citizens, and they already pay high taxes for it.

Conclusion

The basic income has drawn more and more international attention and academic interests since the advent of the fourth industrial revolution. Economic instability caused by the Covid-19 has amplified interest in basic income. Whether positive or negative, the discourse on basic income varies widely across countries. In Sweden, public opinion is generally negative even in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, and it is barely discussed on the public policy table. On the other hand, in Korea, public opinion is not as negative as Sweden, and basic income is actively raised as a policy agenda and even already implemented at some regional and local government levels.

This study reinforces the findings of previous literature, demonstrating that the contrasting attitudes towards basic income and related tax increases in the two countries arise from different perceptions of the social security system and tax burden. It is certain that unconditional cash payment of UBI is useful in mobilising political support. But if the fear of losing income is well covered by social security systems, gaining political support with basic income would be harder than expected. What’s more, because UBI requires an unprecedented amount of fiscal commitment, in countries with high tax burdens, the idea of introducing UBI becomes rather a losing strategy.

As such, it influences policy discourse as well. Basic income is expected to be discussed more actively in developing countries where social security is underdeveloped and the tax burden is low. This may be also true from a technical point of view. Targeted cash benefits and service programmes are surely a better use of scarce resources. But as Banerjee and Duflo (Reference Banerjee and Duflo2019) argues, in developing countries lacking well-developed and clean bureaucracy, even a very small amount of UBI, what they call ‘universal ultra basic income’, may be more effective in reducing poverty and improving health. It seems that UBI is a policy tool worth experimenting in developing countries where poverty is widespread and bureaucracies are underdeveloped rather than in the highly developed societies.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746423000507

Financial support

This research has been funded by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2020K2A9A2A1200023612).