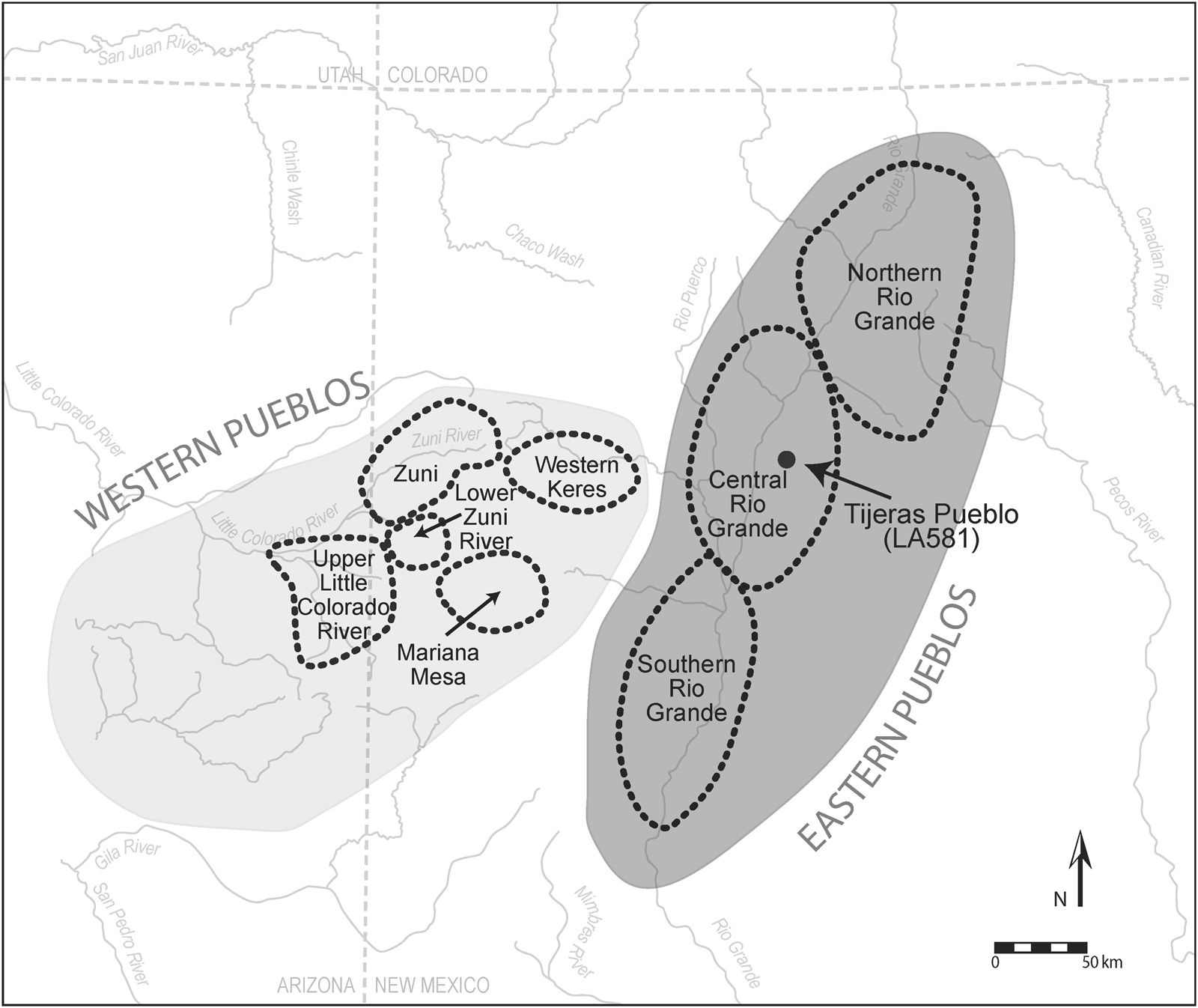

The concept of coalescent communities has been widely used by North American archaeologists and ethnohistorians as a framework for understanding cultural responses to social upheaval (Birch Reference Birch2010, Reference Birch2012; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Huntley, Brett Hill, Lyons and Card2013; Ethridge and Hudson Reference Ethridge, Hudson, Hill and Beaver1998, Reference Ethridge and Hudson2002; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Clark, Doelle and Lyons2004). We view coalescence as a series of agent-driven transformative processes among diverse indigenous societies (Kowalewski Reference Kowalewski, Pluckhahn and Ethridge2006). A coalescent community model emphasizes the creation of novel forms of social integration in the context of groups from different cultural backgrounds living together during periods of crisis (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Huntley, Brett Hill, Lyons and Card2013). Although this framework has been used effectively in the American Southeast (Ethridge Reference Ethridge2010; Ethridge and Hudson Reference Ethridge, Hudson, Hill and Beaver1998, Reference Ethridge and Hudson2002; Galloway Reference Galloway1995), Kowalewski (Reference Kowalewski, Pluckhahn and Ethridge2006, Reference Kowalewski, Gregory and Wilcox2007) has argued that it also has heuristic utility for understanding local responses to social upheaval in other times and places throughout the Americas, pointing specifically to the American Southwest (Figure 1). Archaeologists working in this region have implicitly and explicitly recognized the process of coalescence (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Huntley, Brett Hill, Lyons and Card2013; Duff Reference Duff2002; Ferguson Reference Ferguson, Gregory and Wilcox2007; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Clark, Doelle and Lyons2004; Wilcox et al. Reference Wilcox, Gregory, Brett Hill, Gregory and Wilcox2007), including creating the aptly named Coalescent Community Database (Wilcox and Gregory Reference Wilcox, Gregory, Gregory and Wilcox2007:12).

Figure 1. Map of Eastern and Western Pueblo regions in the American Southwest showing the location of Tijeras Pueblo (LA581) in the central Rio Grande Valley and those Western Pueblo districts where both White Mountain Red Ware and Zuni Glaze Ware were produced.

Here we explore how the concept of coalescence helps us understand the emergence of aggregated settlements and communities in the Albuquerque district (Eckert and Cordell Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004) in the Eastern Pueblo region around the turn of the fourteenth century. At that time, large villages consisting mostly of room blocks loosely arranged around plazas were constructed throughout the district, mirroring contemporaneous trends across much of the Pueblo Southwest (Adams and Duff Reference Adams and Duff2004). We argue that such communities emerged as strategic local responses to increasingly stressful and disruptive social and demographic trends on a macroregional scale.

The period one might think of as the long fourteenth century (AD 1275–1425) was a time of tremendous social change and cultural transformation. Drought, crop failure, malnutrition, the failure of existing social institutions, and occasional violence led to mass migration, the displacement of local communities, and the reorganization of regional and interregional social networks and alliances (Adams and Duff Reference Adams and Duff2004; Glowacki and Van Keuren Reference Glowacki and Van Keuren2011; Spielmann, ed. Reference Spielmann1998). Some areas were completely depopulated, whereas others saw substantial influxes of new populations. In many places, people from diverse ethnic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds chose to come together to remake anew their social worlds from the bits and pieces of existing cultural traditions (Habicht-Mauche Reference Habicht-Mauche, Habicht-Mauche, Eckert and Huntley2006).

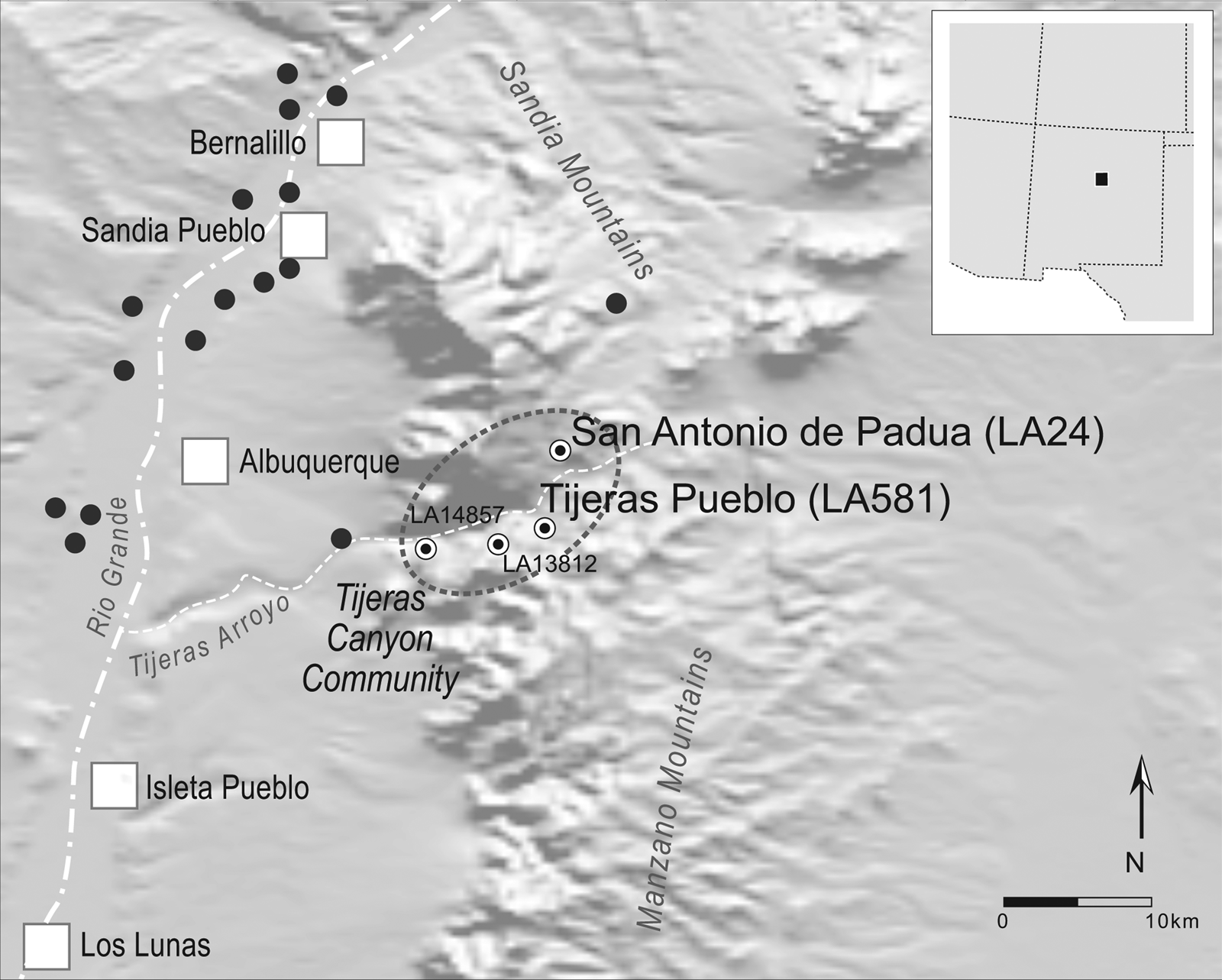

The goal of this study is to examine the processes of coalescence at Tijeras Pueblo (LA581), an Ancestral Pueblo site located along the eastern edge of the Albuquerque district (Eckert and Cordell Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004; Figure 2). As one of the earliest dated aggregated villages in the central Rio Grande Valley and one of the most extensively excavated and best-recorded fourteenth-century sites in the Albuquerque district, Tijeras Pueblo provides us with an excellent opportunity to study one such history of coalescence in greater detail. Specifically, we use ceramic provenance and settlement data from Tijeras Pueblo to explore how the amalgamation of immigrant and autochthonous people, technology, knowledge, and ritual creatively and radically transformed local and regional practices of community and identity formation.

Figure 2. Map of the Albuquerque district in the central Rio Grande Valley showing Tijeras Pueblo (LA581), the Tijeras Canyon Community, and the location of other fourteenth-century aggregated sites in the district (after Eckert and Cordell Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004).

Tijeras Pueblo (LA581)

Previous Work

Tijeras Pueblo is located within the archaeologically defined Albuquerque district. Eckert and Cordell (Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004) defined this district as one of three within the central Rio Grande Valley based on settlement clustering, ceramic design and technology, and historic records. The Albuquerque district correlates closely with the Ancestral Southern Tiwa World as conceptualized by their modern descendants at Sandia and Isleta Pueblos (Jojola Reference Jojola2019), who consider Tijeras Pueblo an ancestral villageFootnote 1 with a place name, Maud'-hued (Seashell Place). In the terminology of archaeologists working in the Eastern Pueblo region, Tijeras Pueblo dates to the transition from the Late Coalition (AD 1275–1325) to the Early Classic (AD 1325–1400) periods (Wendorf and Reed Reference Wendorf and Reed1955). This period corresponds to what is referred to as the Pueblo IV period by archaeologists working in the Western Pueblo region. Multiple academic and salvage archaeological projects have focused on Tijeras Pueblo (e.g., Amaro Reference Amaro1979; Cordell Reference Cordell1975, Reference Cordell1977, Reference Cordell1980; Judge Reference Judge1974; Peckham Reference Peckham1968). By far the most extensive work was undertaken by a series of University of New Mexico (UNM) field schools in the 1970s (Cordell Reference Cordell1975, Reference Cordell1977, Reference Cordell1980; Judge Reference Judge1974), which resulted in about one-third of the site being excavated. The archaeological import of the work done at Tijeras Pueblo cannot be understated; as one of the few Pueblo IV sites in the Albuquerque district not to have been dramatically impacted by historic development prior to excavation, it provides one of the best records of the processes of coalescence in the area.

When farming groups from the Albuquerque basin expanded their settlements eastward during the thirteenth century (Anschuetz Reference Anschuetz, Poore and Montgomery1987; Eckert and Cordell Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004), they strategically built Tijeras Pueblo within a pass between the Sandia and Manzano Mountains. It is here that Tijeras Canyon carves a natural route of travel between the plains of eastern New Mexico and the central Rio Grande Valley. Similarly, Tijeras Pueblo lies astride a major corridor that connected clusters of Early Classic pueblos to the north and to the south. Although the pueblo's upland setting has sometimes been interpreted as marginal, especially for maize production (see various chapters in Cordell Reference Cordell1980), more recent analyses suggest that its crossroads location gave the settlement unique access to diverse natural resources and potentially extensive social networks (Huckell Reference Huckell2019; Jones et al. Reference Jones, Conrad, Newsome, Kemp and Kocer2016; Kirk et al. Reference Kirk, Jones, Ainsworth and Meyer2019).

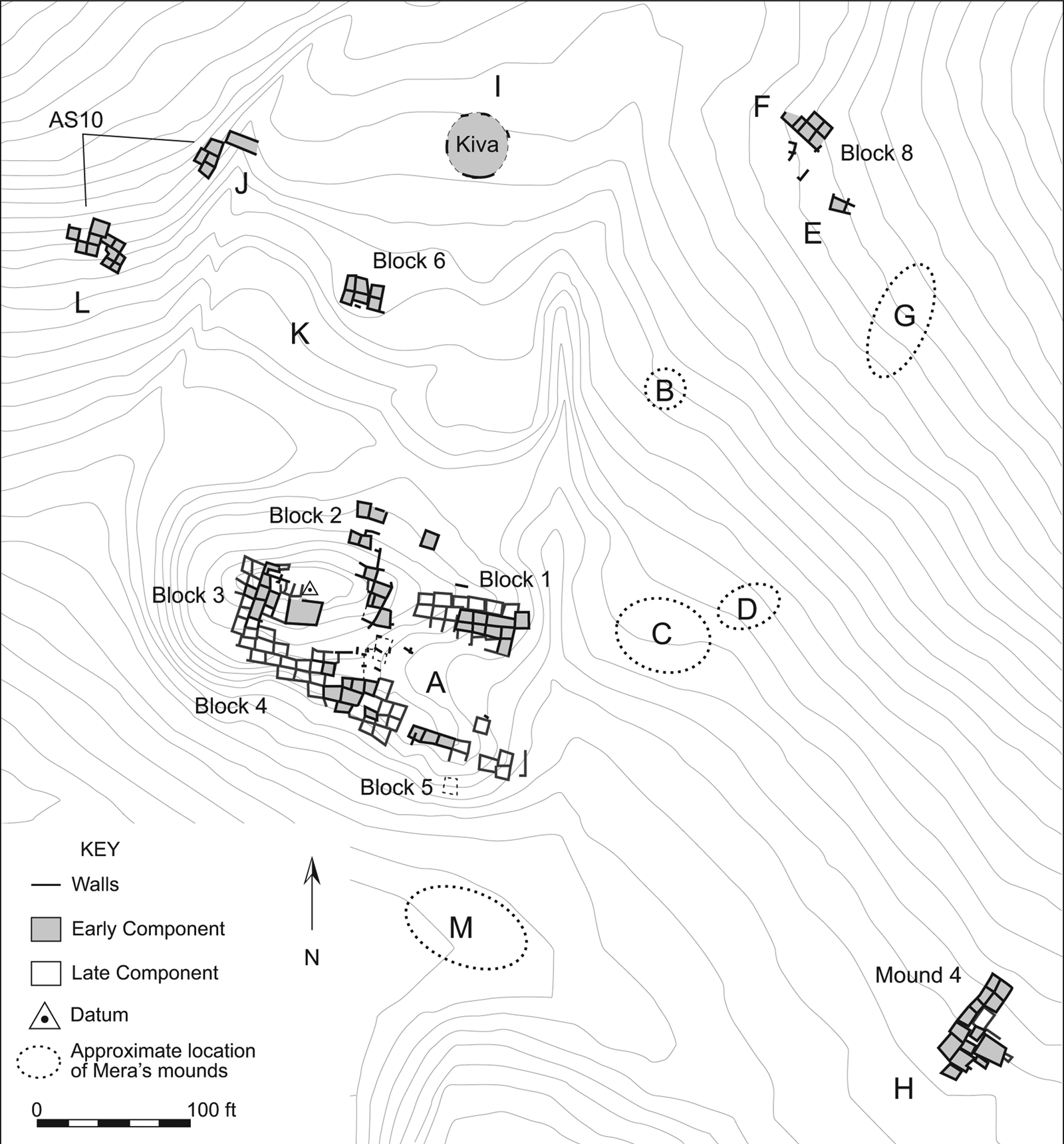

The site consists of a central nucleated structure (Mound A) of approximately 125 rooms and 10–12 smaller outlying room blocks (Cordell and Damp Reference Cordell, Damp, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2010; Cordell et al. Reference Cordell, Deyloff, Mitchell, Snow, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2009). Even though the site has been described as a rather loose collection of adobe room blocks (Peckham Reference Peckham1968:1), a composite plan of the site (Figure 3) shows that in fact residents structured the room blocks into two distinct groups: (1) a north group clustered around a large circular kiva and plaza and (2) a south group focused on the room blocks and rectangular kiva on Mound A, opening out to an east-facing plaza. The presence of multiple tree-ring cutting dates from the latter half of the 1280s and continuously for every decade through the mid-1390s, combined with ceramic cross-dating, indicates that the founding of Tijeras Pueblo lay in the Late Coalition period and that it was continually occupied throughout the Early Classic period (Cordell and Damp Reference Cordell, Damp, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2010). The overall structure of the village, including the north plaza–south plaza/round kiva–rectangular kiva duality, was established by about AD 1315 and appears to have been maintained throughout its occupation into the early fifteenth century.

Figure 3. Composite plan of Tijeras Pueblo (LA581) showing excavated rooms and kivas. Areas of the site that are associated with early component (before AD 1370) construction dates are shaded in gray (based on Cordell and Damp Reference Cordell, Damp, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2010:Figure 2). Unexcavated room blocks or excavated room blocks for which there are no known plans are shown in their approximate location using H. P. Mera's original mound designations (based on Judge Reference Judge1974:Figure 1).

Prior to AD 1325, Tijeras Pueblo appears to have been part of a cluster of early aggregated settlements in Tijeras Canyon (Cordell Reference Cordell1980; Dart Reference Dart1980; Eckert and Cordell Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004; Oakes Reference Oakes1979; Wiseman Reference Wiseman1980). Around AD 1325, the canyon's residents left their smaller settlements in favor of consolidating into the canyon's two largest villages, Tijeras Pueblo and San Antonio de Padua (LA24). A spike in cutting dates during the 1330s (Cordell and Damp Reference Cordell, Damp, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2010) probably corresponds to the expansion of Tijeras Pueblo resulting from this consolidation. At this time, occupation on Mound A consisted of a loose configuration of detached room blocks clustered around a large rectangular kiva (Cordell and Damp Reference Cordell, Damp, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2010). The nucleated U-shaped pueblo that currently dominates Mound A was the product of a major rebuilding effort in the 1390s (see Figure 3). During the early decades of the 1400s, residents of both Tijeras Pueblo and San Antonio de Padua probably moved to join larger nucleated towns in the Albuquerque district or possibly other parts of the Eastern Pueblo region (Cordell and Damp Reference Cordell, Damp, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2010; Eckert and Cordell Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004).

The Current Research

This article summarizes our interpretations of provenance data from glaze-painted pottery recovered at Tijeras Pueblo. Glaze-paint technology is thought to have begun in the Western Pueblo region around AD 1275 (Eckert Reference Eckert, Habicht-Mauche, Eckert and Huntley2006a). The beginning of the Rio Grande Classic period around AD 1325 was initially characterized by the abrupt introduction and rapid spread of red-slipped, glaze-painted pottery into the Eastern Pueblo region. However, at Tijeras Pueblo, Rio Grande Glaze A Red pottery (Figure 4) was recovered from floor contexts in rooms with cutting dates as early as AD 1313 (Cordell Reference Cordell1977), suggesting that the development of the Rio Grande version of glaze-painted pottery may have been an earlier and more complex process than initially conceived. Some early researchers (Reed Reference Reed1949; Shepard Reference Shepard1942; Warren Reference Warren and Snow1976) argued that the seemingly sudden appearance of glaze-painted pottery in the Eastern Pueblo region represented a migration of people from the west. In contrast, other early researchers (Mera Reference Mera1935; Snow Reference Snow and Snow1976; Wendorf and Reed Reference Wendorf and Reed1955) viewed the adoption of Rio Grande Glaze Ware as having resulted primarily through diffusion, possibly accompanied by the movement of a small number of people. We do not find the semantic distinction between “migration” and the “movement of a small number of people” to be particularly productive, because researchers on both sides of this debate concurred that the introduction of glaze-paint technology in the Eastern Pueblo region probably required close contact and extended interactions with knowledgeable actors, most likely from the Western Pueblo region (Herhahn Reference Herhahn, Habicht-Mauche, Eckert and Huntley2006).

Figure 4. An early Rio Grande Glaze Ware bowl (Agua Fria Glaze-on-red) from Tijeras Pueblo (LA581). Catalog No. 78_67_518_DSC_446 (courtesy of Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico). (Color online)

The earliest stratigraphic levels at Tijeras Pueblo, those associated with the founding of the village, are characterized by a predominance of carbon-painted black-on-white pottery typical of contemporaneous sites in the Albuquerque district. This pottery is mixed with an unusually high percentage of either Western Pueblo glaze wares or Western-style glaze-painted polychromes (Judge Reference Judge1974:33–34; see Figure 5). This distinction is an important one, because the prior type assumes production in the Western Pueblo region, whereas the latter assumes production in the Eastern Pueblo region. The site's pottery assemblage, then, hints at its potential for examining the relationship between the spread of people and glaze-paint technology from the Western Pueblo region and processes of coalescent community formation in the central Rio Grande Valley (Eckert Reference Eckert, Habicht-Mauche, Eckert and Huntley2006b).

Figure 5. Zuni Glaze Ware bowl (Heshotauthla Glaze Polychrome) from Tijeras Pueblo (LA581). Catalog No. 78_67_47_DSC_449 (courtesy of Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico). (Color online)

The Western Pueblo glaze ware or Western-style glaze-painted polychrome assemblage recovered from Tijeras Pueblo is dominated by slip colors and designs that match early glaze-painted types in the Zuni Glaze Ware series (Eckert Reference Eckert, Habicht-Mauche, Eckert and Huntley2006a). Sherds that could be identified as associated with early Zuni Glaze Ware series types made up 15% of the analyzed glaze ware assemblage from Tijeras Pueblo, compared to 23% identified as early Rio Grande Glaze A. Specifically, the most common early Western-style glaze-painted pottery types that occur at Tijeras Pueblo parallel the slip colors, designs, and layouts of Heshotauthla Glaze-on-red and Glaze Polychrome. Although often associated with the Zuni district, Zuni Glaze Ware types with Heshotauthla-style designs—Heshotauthla Glaze-on-red and Glaze Polychrome and some Kwakina Glaze Polychrome—were actually produced over a large swath of the Western Pueblo region from about AD 1275 to 1425 (Duff Reference Duff2002; Eckert Reference Eckert, Habicht-Mauche, Eckert and Huntley2006a).

In addition to the Heshotauthla-style Zuni Glaze Ware, a small number of sherds (N = 30, or 1% of the glaze ware assemblage) identified as White Mountain Red Ware types were recovered from Tijeras Pueblo. Most (N = 26) were typed as glaze-painted St. Johns Black-on-red or Polychrome (AD 1275–1300), which were also made widely throughout the Western Pueblo region. Although St. Johns Polychrome is generally categorized as part of the White Mountain Red Ware series (Carlson Reference Carlson1970; Colton and Hargrave Reference Colton and Hargrave1937), the glaze-painted variant is also considered a precursor to the Zuni Glaze Ware series (Carlson Reference Carlson1970).

The abundance of Western Pueblo glaze wares or Western-style glaze-painted sherds in the earliest stratigraphic levels at Tijeras Pueblo raises some interesting research questions that we attempt to address in this article. First, were any of the Western-style glaze-painted pots imported from the Western Pueblo region, and if so from where? Or, conversely, were any of the Western-style glaze-painted pots produced locally in the Albuquerque district? Second, what does the presence of these Western-style pots suggest about how interregional networks may have facilitated the migration of people from the west to the east? Third, and finally, how does tracing the movement of pots and the specialized knowledge required to make and use them allow us to better understand processes of coalescent community formation as they played out at Tijeras Pueblo and more broadly within the Albuquerque district?

Methods

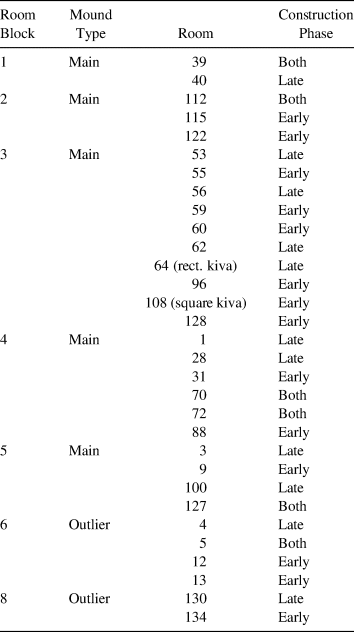

Habicht-Mauche selected a sample of pottery to analyze from the 1970s UNM field school excavations, focusing on fill from excavated rooms with tree-ring dates that spanned the entirety of the villages’ occupation and that were broadly distributed across all room blocks and room types (Table 1). Sherds from one of the deep stratigraphic test units (30N/20W) that showed evidence for the gradual introduction and increased use of Rio Grande Glaze A Red at the site were also analyzed. This sample yielded approximately 3,000 decorated vessel fragments and more than 12,000 utility ware fragments. Habicht-Mauche recorded values for around 30 specific technological, formal, and stylistic attributes for each sherd (tDAR id: 458589; DOI:10.6067/XCV8458589). Every decorated sherd was examined using a 40× binocular microscope to make preliminary visual temper/paste identifications. A nonrandom sample of utility ware sherds was also examined under low-power magnification. Two sherds from each of the major temper/paste groups were thin-sectioned for petrographic analysis.

Table 1. UNM Field School Proveniences Sampled for Pottery Analysis from Tijeras Pueblo (LA581).

Notes: Samples are from both the main mound (room blocks 1–5) and the outliers (room blocks 6 and 8). Early Construction phase is AD 1289–1369; Late Construction phase is AD 1370–1395.

Petrographic slides were made at the UCSC Mineral Preparation Laboratory, and thin sections were qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed using an Olympus BH-2 optical microscope set up for transmitted polarized light microscopy. With few exceptions petrographic identifications matched well with initial binocular sorting categories. Approximately 30 sherds from the six most common glaze ware paste/temper groups, plus 30 utility ware sherds, were selected for neutron activation analysis (NAA) and sent to Texas A&M University (TAMU), College Station. In addition, chips from all thin-section and NAA voucher sherds were refired in an electric kiln in an oxidizing atmosphere to a maximum temperature of 900°C with a hold time of 60 minutes. This was done to standardize paste colors for comparison with local clays and to correlate paste colors with petrographic and NAA results.

We chose NAA because it is generally considered the most powerful chemical characterization technique for pottery analysis (Arnold et al. Reference Arnold, Neff, Bishop, Glasscock and Chilton1999; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Canouts, DeAtley, Qöyawayma and Aikens1988; Duff Reference Duff1999, Reference Duff2002; Glowacki and Neff Reference Glowacki and Neff2002; Huntley Reference Huntley2004, Reference Huntley2008). In addition, NAA has been the pottery sourcing method of choice of archaeologists working in the Western Pueblo region (Duff Reference Duff1999; Huntley Reference Huntley2004; Mills Reference Mills, Gregory and Wilcox2007a; Peeples Reference Peeples2018; Schachner Reference Schachner2012; Triadan Reference Triadan1997). As a result, there is an extensive existing dataset with which we could compare the Tijeras Pueblo material (Peeples et al. Reference Peeples, Duff, Huntley, Schachner, Laumbach, Glascock and Ferguson2018). Initially, 220 sherds were selected for NAA from the Tijeras Pueblo assemblage. All samples from Tijeras Pueblo were processed by Eckert at the TAMU Center for Chemical Characterization and analyzed using NAA at the TAMU Nuclear Science Center's 1 MW TRIGA research reactor. Sample preparation and analysis were conducted according to established EAL methods (James et al. Reference James, Brewington and Shafer1995), which follow procedures outlined at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR). Initial results reported concentrations for 33 elements: Al, As, Ba, Ca, Ce, Co, Cr, Dy, Eu, Fe, Hf, K, La, Lu, Na, Nd, Ni, Mg, Mn, Sb, Sc, Sm, Sr, Rb, Ta, Tb, Th, Ti, U, V, Yb, Zn, and Zr. Quality control determined that one sample was problematic, and early rounds of statistics determined that another sample was an outlier. Both samples were removed from the analyses discussed in the next section.

Parts-per-million (ppm) elemental data collected from the NAA were quantified using an approach thoroughly outlined by many (but see Glowacki [Reference Glowacki2006] for an exceptionally clear discussion). Briefly, Eckert performed all statistical analyses and created figures using XLSTAT 2018.6. The raw ppm data were converted to base 10 logarithms to compensate for differences in magnitude between major and trace elements and to produce a more nearly normal distribution. A standard suite of statistical techniques was used to explore patterning in the data, to assign sherds to compositional groups, and to evaluate group membership probabilities. These techniques included bivariate scatter plots, k-means clustering, principal components analysis (PCA), discriminant analysis (DA), and Mahalanobis distances (MD). Although not the only statistical methods used in compositional studies (Baxter Reference Baxter2003; Bishop et al. Reference Bishop, Rands, Holley and Schiffer1982), these techniques are commonly used and were selected as the best suite of techniques given our sample size. Most of these techniques are not conducive to graphical display, and even those that are conducive often fail to adequately summarize multivariate relationships involving hundreds of cases and up to 33 variables. As such, we provided figures and summary tables that speak to the evidence relevant to the discussion at hand.

Results

Petrography and Refiring Experiments

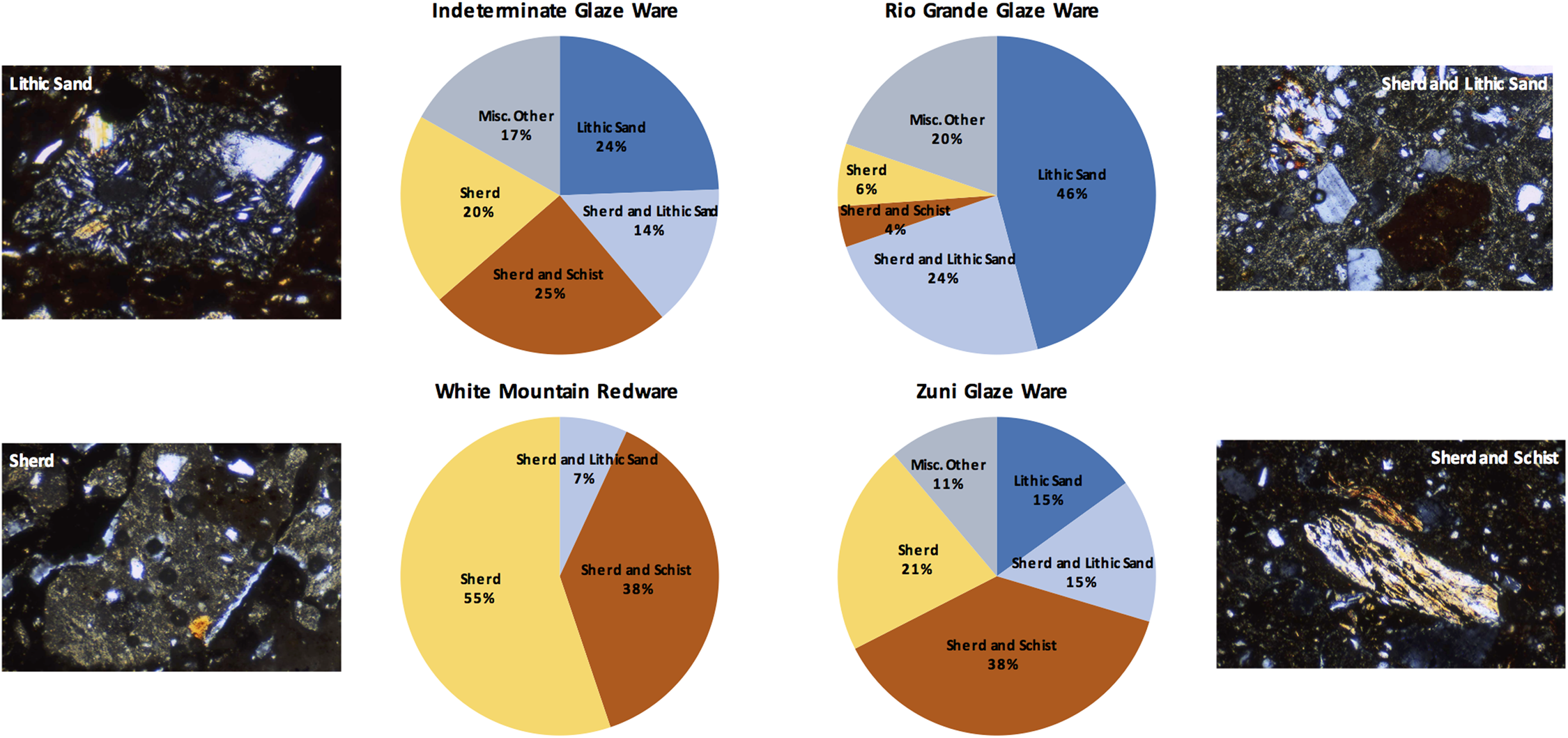

Visual sorting of ceramic pastes, verified by petrographic identification, demonstrated that the overwhelming majority (more than 80%) of glaze-painted pottery recovered from Tijeras Pueblo could be assigned to one of four temper groups: lithic sand, sherd and lithic sand, sherd and schist, or sherd (Figure 6). All refired chips could be assigned to one of two broad paste color categories: red (Munsell 5YR5/6-8; 5YR6/6-8; 7.5YR6/6-8; 7.5YR7/6) or white (Munsell 7.5YR8/3-4; 10YR8/3-4). Although the four major temper categories were identified across all three glaze ware categories—Zuni Glaze Ware, White Mountain Red Ware, and Rio Grande Glaze Ware—combined refired paste color and temper patterns were noted that we interpret as reflecting possible regional preferences in resource selection and processing strategies (Table 2).

Figure 6. Relative ratio of the major temper/paste groups by ware among glaze-painted pottery from Tijeras Pueblo (LA581). All images were photographed at 200× magnification in cross-polarized light (photomicrographs taken by Judith A. Habicht-Mauche). (Color online)

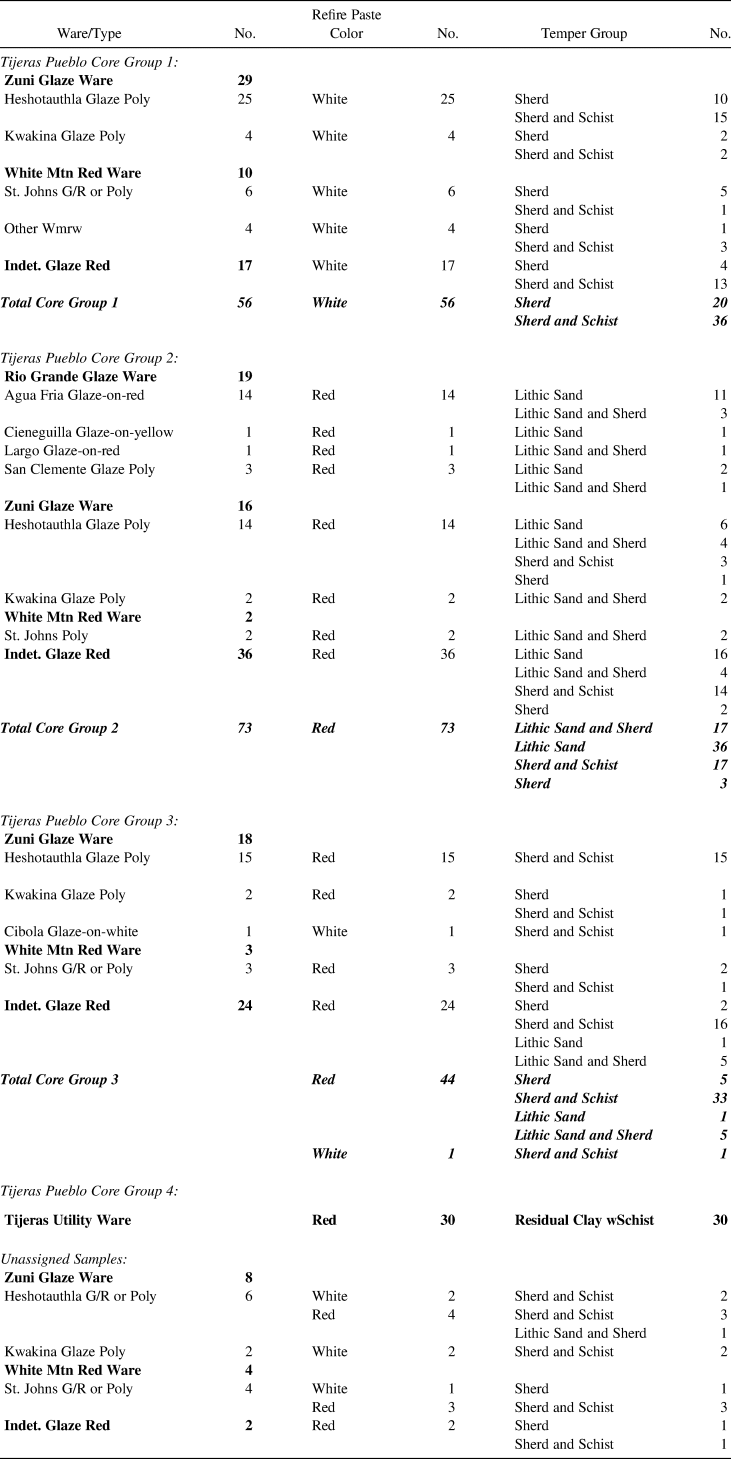

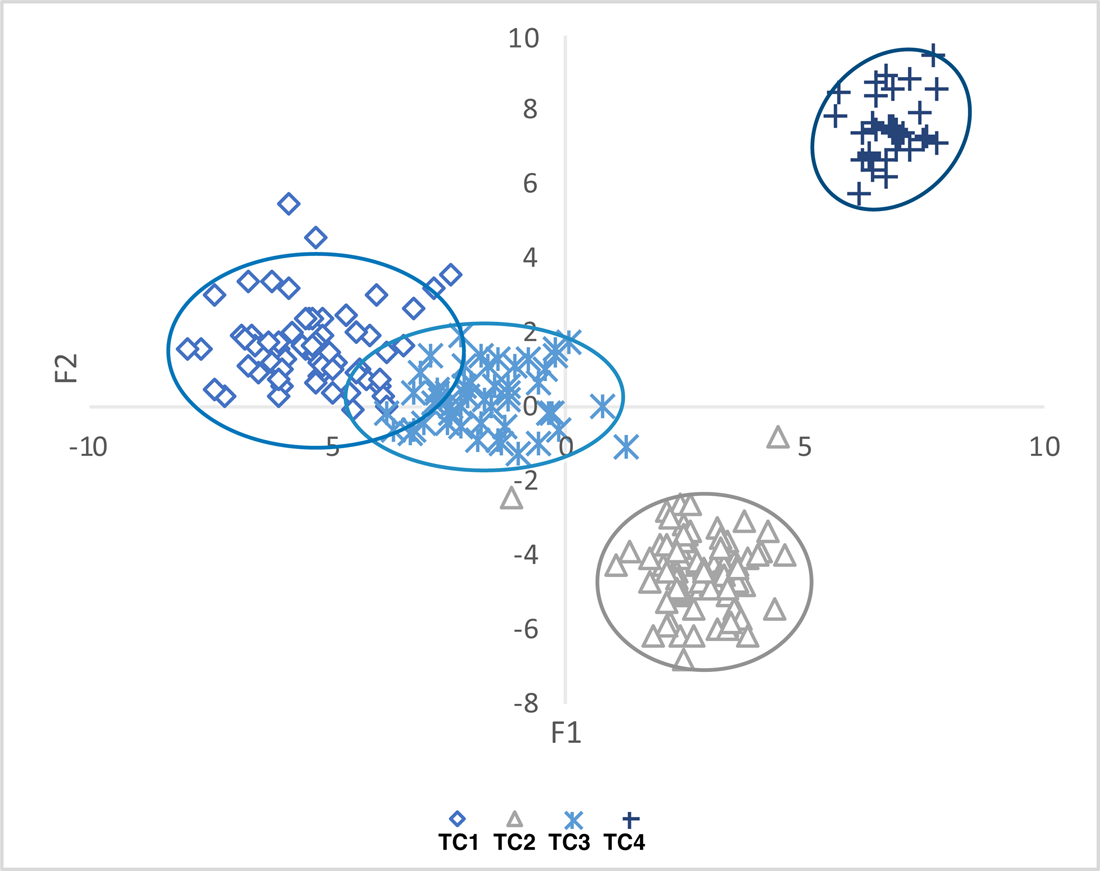

Table 2. Summary of Tijeras Pueblo (LA581) NAA Core Group Characteristics.

Notes: White = 7.5YR8/3–4 and 10YR8/3–4; Red = 5YR5/6–8, 5YR6/6–8, 7.5YR6/6–8, and 7.5YR7/6.

The overwhelming majority of Rio Grande Glaze Ware types recovered from Tijeras Pueblo are characterized by the use of red-firing sedimentary clays with moderate to coarse mixed lithic sand inclusions, often but not always tempered with ground sherd. These sherds are from pots that were produced locally in the Albuquerque district, possibly at Tijeras Pueblo (Shepard Reference Shepard1942; Warren Reference Warren and Snow1976). All the Rio Grande Glaze Ware sherds selected for NAA from Tijeras Pueblo had this paste and temper combination. Among the Rio Grande Glaze Ware sherds recovered from Tijeras Pueblo, various other miscellaneous tempers were also noted, including an eclectic mix of ground rock tempers that are associated with known sources of glaze ware production in other districts of the Rio Grande region (Eckert Reference Eckert2008; Habicht-Mauche Reference Habicht-Mauche1993: Shepard Reference Shepard1942; Warren Reference Warren and Snow1976).

Paste and temper patterning for the Western-style glaze-painted types is more complex than that observed for the Rio Grande Glaze Ware types. Sherds identified as St. Johns types, along with the other rare White Mountain Red Ware sherds, are characterized predominantly by sherd temper, often in white firing pastes, although examples of red firing pastes with sherd, sherd and schist, or sherd and lithic sand tempers are also present. More than half (57%) of the White Mountain Red Ware sherds selected for NAA refired white; the rest (43%) refired red. All the White Mountain Red Ware sherds that refired red were identified as St. Johns types; the few sherds possibly identified as later White Mountain Red Wares all refired white.

The Zuni Glaze Ware sherds are the most diverse in terms of both paste color and temper. A plurality (38%) of the Zuni Glaze Ware examined was characterized by red-firing pastes with ground sherd temper and finely divided schist fragments. However, almost an equal amount (30%) was characterized by red-firing pastes with lithic sand or sherd and lithic sand temper, suggesting local production in the Albuquerque district. In addition, some (11%) of the Zuni Glaze Ware sherds were tempered with various materials that are typically associated with production in other areas of the Eastern Pueblo region. Overall, almost 40% of the Zuni Glaze Ware sherds appear to have been from pots that were actually produced at a variety of Eastern Pueblo communities. About 20% of the remaining Zuni Glaze Ware sherds were tempered with sherd, often with white-firing pastes. The Zuni Glaze Ware sherds represented in the NAA sample were a mix of red-firing pastes (53%) and white-firing pastes (47%).

In sum, the presence of Western-style glaze-painted types at Tijeras Pueblo with a paste (red-firing) and temper (lithic sand, sometimes mixed with sherd) combination associated with local production in the Albuquerque district suggests that many of the sherds recovered from the site were very competent locally made copies of early red-slipped Western Pueblo types. However, based on our current understanding of paste colors and temper preferences among Albuquerque district potters, it seems unlikely that the white-firing glaze-painted sherds recovered from Tijeras Pueblo were made locally. The source of the red-firing pastes with sherd temper or sherd and schist temper was also impossible to pinpoint using only refiring, visual paste sorting, and petrography. It seemed highly probable that at least some of this pottery had been imported from the Western Pueblo region. As such, we turned to NAA to explore in greater detail the provenance of Western-style glaze-painted sherds recovered from Tijeras Pueblo.

Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA)

Tijeras Pueblo. The dataset of 218 samples characterized by 27 elements can be divided into four composition clusters (TC1, TC2, TC3, and TC4) based on the “best solution” for k-means analysis. Samples plotted by k-means cluster analysis using the first two PCA components and the first two DA factors (Figure 7) show comfortable agreement between the methods. Examination of bivariate plots by element further confirms the separation between the k-mean clusters. These four compositional clusters align well with the paste refire color and temper patterns by ware described earlier (Table 2). All the sherds that clustered in TC1 refired white and were tempered with sherd or sherd and schist temper; only Western-style glaze-painted sherds were included in this cluster. With one exception, the few non-St. Johns type White Mountain Red Ware sherds analyzed fell in this group. TC2 is composed entirely of sherds with red pastes and lithic sand or lithic sand and sherd temper; all sherds analyzed that could unambiguously be identified as Rio Grande Glaze Ware clustered in TC2, along with some Western-style glaze-painted sherds. All the sherds, except one, that clustered in TC3 also had red-firing pastes but with predominantly sherd or sherd and schist temper; the identifiable sherds in this cluster include only Western-style glaze-painted sherds. TC4 consists entirely of the 30 utility ware sherds, which were made using a very distinctive coarse micaceous residual clay found widely throughout the Sandia and Manzano Mountains.

Figure 7. Plot of NAA results for Tijeras Pueblo (LA581) glaze ware sample. First two functions of DA analysis plotted by k-means 4-cluster solution. Ovals represent 95% confidence interval for membership. (Color online)

We interpret these results as demonstrating that the sherds that cluster in both TC2 and TC4 are from pots that had been made locally in the Albuquerque district by potters working either at or near Tijeras Pueblo. The sherds that cluster in TC1 and TC3, in contrast, are more likely to have been imported from outside the Albuquerque district. Given that all the identifiable sherds in these two clusters are associated with Western-style glaze ware series types, that sherd temper was the dominant practice among Western Pueblo potters, and that white-firing pastes are more common in the west, it seemed likely that these clusters represented sherds that came from pots produced by potters working in the Western Pueblo region. With that in mind, we decided to compare the chemical compositional data for these two clusters with NAA data for pottery with Western Pueblo provenances.

Comparison with Western Pueblo Data. The second step in our NAA study was to compare the chemical compositional data for Western-style glaze-painted sherds recovered from Tijeras Pueblo with NAA data for pottery recovered from the Western Pueblo region. We initially ran TC1 and TC3 against the entire Western Pueblo NAA dataset (Duff Reference Duff1999; Eckert et al. Reference Eckert, Hill and Habicht-Mauche2017; Huntley Reference Huntley2004; Peeples Reference Peeples2018; Schachner Reference Schachner2012; Triadan Reference Triadan1997). The 1,859 samples represented 31 statistically defined core groups; these core groups have been assigned Western Pueblo provenances by previous researchers. Values for Ni, K, Na, Ti, and V were removed from the combined analysis, because measurements of these elements were not consistently reliable across studies. Tijeras Pueblo samples were compared to the entire database, as well as subsamples of the database (including only decorated wares or only Western Pueblo glaze wares). Regardless of the comparative subsample, our K-means, PCA, and DA results consistently created new core groups that crosscut statistical core groups defined in earlier studies, making it difficult to assign any specific Western Pueblo district provenance to the Tijeras Pueblo samples.

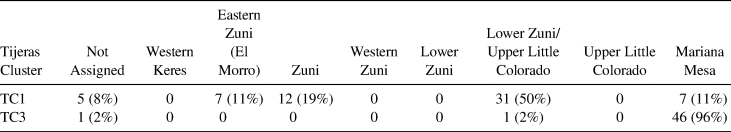

To attempt to establish more specific production provenances for TC1 and TC3, we decided to combine statistical core groups from the Western Pueblo region by archaeological district. In addition, we only included data from glaze-painted decorated pottery types. The resulting database consisted of 857 samples grouped into seven districts. These samples sorted into 10 compositional groups based on the “best solution” for k-means analysis. Samples plotted by k-means cluster analysis using the first two PCA components and DA factors show comfortable agreement between the methods, although DA seems to separate some groups more clearly. Using MD, the k-means 10-cluster solution was pared down to “core members” by setting criteria for group membership at 95% confidence of belonging to one group and less than 1% chance of belonging to any other group. Examination of only the core members in the remainder of the analysis provides more confidence in the robustness of observed patterns.

In some instances, the 10-cluster solution separated samples from the same archaeological district; this is not surprising, because we combined statistical core groups from previous studies into the same district. In other instances, the 10-cluster solution grouped samples from different districts into the same cluster; this is also not necessarily surprising given that some clay-bearing geological formations crosscut these districts. Ultimately, though, we are concerned here with the Tijeras Pueblo samples and so focus only on those clusters that have Tijeras Pueblo samples as core members. TC3 provides the clearest results (Table 3), occurring in a cluster that consists only of TC3, TC1, and samples from Techado Spring Pueblo (LA6010) in the Mariana Mesa district; 96% of the TC3 samples, 68% of the Techado Spring Pueblo samples, and 11% of the TC1 samples group in this cluster. We are currently comfortable interpreting these results as suggesting that the majority of the TC3 samples were produced in the Mariana Mesa district. TC1 is more diverse, but 50% of the samples cluster with the combined Lower Zuni River (Jaralosa Draw)/Upper Little Colorado core group samples. We interpret these results as suggesting that most of the TC1 samples are from pots that were likely produced in either or both geologically similar districts. The rest of the TC1 samples can be assigned to the Zuni district (19%), the El Morro district (11%), and the Mariana Mesa district (11%).

Table 3. Comparison of Nonlocal NAA Core Compositional Groups from Tijeras Pueblo and Those from the Western Pueblo Database.

Discussion

The overwhelming majority of Rio Grande Glaze Ware sherds from Tijeras Pueblo are characterized by the use of red-firing sedimentary clays with moderate to course mixed lithic sand inclusions, often but not always tempered with ground sherd. This material preference has long been associated with decorated pottery known to have been produced in the Albuquerque district of the central Rio Grande Valley (Eckert Reference Eckert2008; Shepard Reference Shepard1942; Warren Reference Warren and Snow1976). Alluvial sediments with varying mixes of schist, granite, basalt, and rhyolite are common throughout the area, although not in the immediate vicinity of Tijeras Pueblo. The nearest source of these sediments would have been 10–12 km away at the western end of Tijeras Canyon, which exceeds Arnold's (Reference Arnold1985) ethnographically modeled threshold of 7 km for the local acquisition of clays and tempers. Travel through the Tijeras Canyon pass to the valley, however, would have been relatively easy and probably quite common; given that many of the original residents of the coalescent Tijeras Canyon Community likely came from the Albuquerque Valley, potters would have been familiar with these sources and comfortable with their use. It is also possible that the inhabitants of Tijeras Pueblo and the broader Tijeras Canyon Community were obtaining some or even most of their glaze-painted pottery from neighboring communities in the Albuquerque Valley.

The more exciting finding is that about 30% of the identifiable Zuni Glaze Ware and around 7% of the White Mountain Red Ware samples analyzed from Tijeras Pueblo were made locally as well. These locally produced Zuni Glaze Ware and White Mountain Red Ware are very credible copies of Western-style glaze ware types. Their appearance in some of the earliest stratigraphic levels and room contexts at Tijeras Pueblo would seem to provide at least circumstantial evidence that Western Pueblo immigrants were present in the Albuquerque district by the late thirteenth century and may have been among the original settlers at Tijeras Pueblo.

The clearest link between Tijeras Pueblo and the Western Pueblo region, as revealed by the comparative NAA analysis, appears to have been with the Mariana Mesa district (see Figure 1). Virtually all (96%) of the samples in NAA core group TC3 clustered with a sample of sherds recovered from Techado Spring Pueblo. In addition, our paste and temper descriptions compare favorably with limited published descriptions of paste and temper local to the Mariana Mesa district (McGimsey Reference McGimsey and Charles1980; Smith and Robertson Reference Smith and Robertson2009). This district seems to have been rapidly, and possibly violently, depopulated around the turn of the fourteenth century (McGimsey Reference McGimsey and Charles1980; Peeples Reference Peeples2011, Reference Peeples2018; Smith and Robertson Reference Smith and Robertson2009). As residents of this district were seeking to emigrate, at least some of them may have turned toward communities in Tijeras Canyon where they had already established relationships.

Our results also suggest that very little of the Heshotauthla-style Zuni Glaze Ware pottery recovered from Tijeras Pueblo actually came from the Zuni district. Our findings conform with Duff (Reference Duff2002), who showed that most of the Zuni Glaze Ware circulating among communities in the Western Pueblo region during the early Pueblo IV period came from the Upper Little Colorado district. In particular, most of the white-firing Western-style glaze ware sherds associated with the TC1 core group from Tijeras Pueblo clustered statistically with pottery argued to have been made in either the Upper Little Colorado district or the nearby Lower Zuni River district (see Figure 1). Glaze wares from both districts are characterized by light-firing pastes, probably made from nonferrous clays derived from nearby Cretaceous formations. Habicht-Mauche has been able to visually compare TC1 cluster sherds from Tijeras Pueblo with voucher sherds from both districts that had been analyzed using NAA by Duff (Reference Duff1999, Reference Duff2002), confirming close similarities among these samples in terms of slip color, paste refire color, and paste/temper composition.

Coalescence and the Origin of Rio Grande Glaze Ware

Immigration

The predominance of carbon-painted Rio Grande white wares at all Late Coalition sites in Tijeras Canyon, including the lowest levels of the middens at Tijeras Pueblo, suggests that most of the earliest inhabitants of this new community were drawn locally from among existing thirteenth-century settlements in the Albuquerque district. However, we present evidence here for the presence of both imported and locally made copies of Western-style glaze wares, including in contexts associated with the earliest occupation of Tijeras Pueblo. We argue that the locally made copies are so exact as often to be indistinguishable from the imports, which points to the direct immigration of potters with the technical knowledge to produce them. Our NAA data suggest that the inhabitants of Tijeras Pueblo had strong ties to people living in some of the more ephemeral areas of the Western Pueblo World, including the Mariana Mesa district that was largely depopulated by AD 1300 (McGimsey Reference McGimsey and Charles1980; Smith and Robertson Reference Smith and Robertson2009) and the Upper Little Colorado region, which experienced substantial settlement reorganization, likely with some outmigration, around AD 1275–1280 (Duff Reference Duff1999, Reference Duff2002).

We argue that immigrants from these districts were present in the Albuquerque district by the late thirteenth century and that at least some of the founders of the Tijeras Canyon Community were immigrants from these marginal areas. It makes sense that these immigrants did not come from one of the better-known districts of the Western Pueblo region, such as Zuni or the Western Keres (Acoma) districts. These districts are known to have had large, relatively stable communities that flourished throughout the fourteenth century and beyond (Adams and Duff Reference Adams and Duff2004). Rather, immigrants to the Albuquerque district were from places that, for whatever reason, failed to endure. The community that came together at Tijeras Pueblo and within Tijeras Canyon around the turn of the fourteenth century was likely an eclectic, multiethnic mix of people from diverse origins and with differing cultural beliefs and practices. This is the very definition of coalescence.

Coalescence

Even if one does not accept our argument for Western Pueblo immigrants at Tijeras Pueblo, the village was clearly founded around AD 1290 as one of a cluster of aggregated settlements of modest size in Tijeras Canyon (Cordell Reference Cordell1980; Dart Reference Dart1980; Eckert and Cordell Reference Eckert, Cordell, Charles Adams and Duff2004; Oakes Reference Oakes1979; Wiseman Reference Wiseman1980), which we argue functioned as a single emergent coalescent community. We have found the coalescent communities framework (Kowalewski Reference Kowalewski, Pluckhahn and Ethridge2006) to be particularly productive for understanding the processes of settlement aggregation occurring in Tijeras Canyon during the fourteenth century. This concept emphasizes the diverse origins and cultural histories of the groups that come together to form new communities and novel cultural identities in ways that focus on collective survivance and highlight the complexity of interactions as they play out historically in any particular emergent community.

Part of the founding population of this new community probably came from small farming settlements that had existed in the canyon since at least AD 1100. Even though its upland location may have limited maize production (Cordell Reference Cordell1980; Van West Reference Van West, McBrinn and Huntley2022), additional settlers from outside the canyon may have been drawn to the Tijeras Canyon Community because of the area's unique access to economically and ritually significant resources from a variety of elevational and environmental settings (Ferguson and Hart Reference Ferguson and Richard Hart1990; Huckell Reference Huckell2019; Kirk et al. Reference Kirk, Jones, Ainsworth and Meyer2019). The strategic location of this new cluster of small, aggregated settlements at the intersection of major east–west and north–south cultural corridors may have provided its inhabitants with the opportunity to develop and control expansive intra- and interregional economic and social networks, linking people up and down the Rio Grande and from the Western Pueblos to the Great Plains.

Tijeras Pueblo underwent a building boom in the 1310s (Cordell and Damp Reference Cordell, Damp, Brown, Armstrong, Brugge and Condie2010; Judge Reference Judge1974), as processes of aggregation and coalescence in the canyon continued. By 1313, Tijeras Pueblo had taken on its distinctive dual structure, with a northern section consisting of detached room blocks clustered around a large circular kiva and open plaza and a southern section focused on a tighter agglomeration of rooms adjacent to a large square kiva and lacking as clearly a defined plaza (see Figure 3). As with other coalescent communities in the American Southwest (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Huntley, Brett Hill, Lyons and Card2013; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Clark, Doelle and Lyons2004), these changes in spatial organization may reflect the presence of residents of diverse origins with varied interregional connections. Specifically, these two distinct sections of Tijeras Pueblo may reflect the presence of people with different ideas about proper settlement structure living among each other in the same village.

This north–south duality might also be linked to the historical emergence of the Southern Tiwa moiety system, which continues to structure ritual and social life at the Pueblo of Isleta up to the present day (Ellis Reference Ellis and Ortiz1979). Fowles (Reference Fowles2005) has argued that Eastern Pueblo moiety systems emerged within the context of diverse local histories of migration and coalescence in the Rio Grande region around the turn of the thirteenth century. The variability in religious architecture and integrative space within the two halves of the site is particularly intriguing, suggesting the presence of multiple and perhaps complementary ritual complexes. We argue that one of these complexes was probably introduced to the Albuquerque district by Western Pueblo migrants and was associated with the production and use of Heshotauthla-style Zuni Glaze Ware. We thus refer to this complex as the Heshotauthla Ritual Complex.

The Heshotauthla Ritual Complex

In the American Southwest, social aspects associated with the development of coalescent communities include the formation of meta-identities (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Huntley, Brett Hill, Lyons and Card2013), demographic reorganization (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Clark, Doelle and Lyons2004), and ideologies that emphasize world renewal and inclusion (Adams Reference Adams1991; Crown Reference Crown1994). Ritual practices associated with this last aspect have often been considered in terms of the spread of pan-regional ideologies such as Katsina ceremonialism (e.g., Adams Reference Adams1991) or the Southwest Regional Cult (e.g., Crown Reference Crown1994). Although sharing many features of ideology and iconography, these emergent ritual practices have proven to be more prolific, diverse, and localized than initially recognized (e.g., Duff Reference Duff2002). Thus, we envision the Heshotauthla Ritual Complex as one of many interrelated ritual complexes that were associated with the production, distribution, and use of a variety of diverse, yet similar, polychrome traditions throughout the Ancestral Pueblo World during the Pueblo IV period.

The Heshotauthla Ritual Complex—with what we imagine to be associated sacred knowledge, songs, ritual performances, and paraphernalia—may have linked communities, west to east, across a broad area of the Ancestral Pueblo World from Zuni to the Upper Little Colorado, Mariana Mesa, Western Keres, and central Rio Grande districts; these were all areas where Heshotauthla-style glaze-painted pottery was dominant around the turn of the fourteenth century. The spread of these ideologies and ritual practices has most often been discussed in functionalist terms, emphasizing the role that new religious institutions played in integrating populations with different backgrounds, stabilizing recently nucleated settlements, and preventing social disintegration (Adams Reference Adams1991; Crown Reference Crown1994). Also significant, however, may have been how these diverse ideas and practices came together historically within the unique context of specific coalescent communities in ways that creatively catalyzed the emergence of novel local identities.

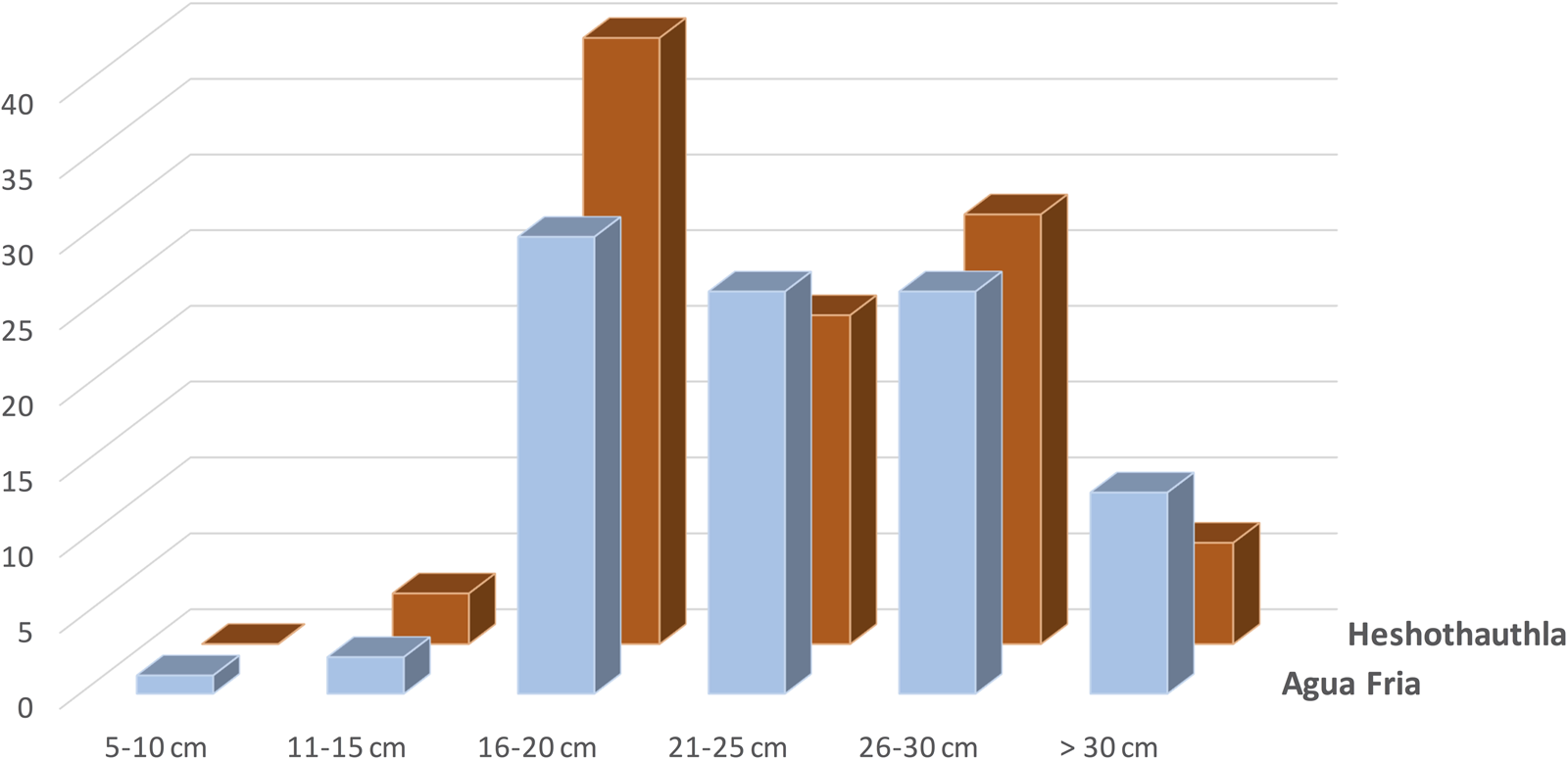

One practice that appears to have been shared across many of these diverse sects, including the Heshotauthla Ritual Complex, is the importance of communal feasting (Eckert Reference Eckert2008; Mills Reference Mills2007b; Potter Reference Potter2000; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Spielmann1998). The widespread adoption of glaze-painted and other polychrome wares across the Ancestral Pueblo World has been argued to reflect communal feasting practices in part because these wares are often associated with the production of a whole new class of large serving bowls (>25 cm diameter; Crown Reference Crown1994; Mills Reference Mills2007b; Potter Reference Potter2000; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Spielmann1998). This large bowl size is clearly present in both the Heshotauthla-style and early Rio Grande-style glaze-painted bowl fragments recovered from Tijeras Pueblo (Figure 8). Following Spielmann (Reference Spielmann2002:202), we argue that smaller glaze ware bowls were probably used as everyday household serving bowls, but it was the technical craftsmanship and distinctive physical characteristics of these glaze-painted wares—their bright colors, highly burnished surfaces, glossy paint, and iconographic designs—that made them suitable for use in ritual contexts such as communal feasting. The presence of significant numbers of both imported and locally produced Heshotauthla-style glaze-painted feast bowls at Tijeras Pueblo suggests that at least some members of the community understood the proper use and display of these vessels and their symbolic significance; in other words, they were competent and knowledgeable participants in the Heshotauthla Ritual Complex.

Figure 8. Comparison of the relative distribution of bowl rim diameters (in centimeters) between Agua Fria Glaze-on-red (83 measurable rims) and Heshotauthla Glaze Polychrome (60 measurable rims) vessel fragments from Tijeras Pueblo (LA581).

Conclusion

Sometime before AD 1320 a local version of red-slipped, glaze-painted pottery began to be made throughout the Albuquerque district. The recovery of the earliest dated Rio Grande Glaze A Red (Agua Fria Glaze-on-red) pottery from the floor contexts of two rooms at Tijeras Pueblo suggests that the coalescent Tijeras Canyon Community participated, along with neighboring communities in the Albuquerque Valley, in the early development and use of this new style. This innovation possibly reflects the emergence of a distinctly local variant of the Heshotauthla Ritual Complex that, while sharing knowledge and practices introduced by Western Pueblo immigrants, was collectively reshaped and reinterpreted within a wholly new local context. At about the same time as the development of this new local style of glaze-painted pottery, the population of the Tijeras Canyon Community appears to have further aggregated into Tijeras Pueblo and San Antonio de Padua. These two large, nucleated pueblos dominated the Tijeras Canyon landscape throughout the rest of the fourteenth century. This transition happened within one generation of the initial occupation of Tijeras Pueblo and may reflect the emergence of a more unified collective cultural identity, one that may have come to be shared with other coalescent communities throughout the Albuquerque district. These communities, with their shared histories, ideologies, knowledge, and practices, came to define the historical and cultural landscape of the Southern Tiwa World, as it was encountered by the Spanish in the sixteenth century and as it largely continues to be conceived by the people of Sandia and Isleta pueblos today.

Acknowledgments

This article builds on research previously presented at several conferences (Habicht-Mauche and Eckert Reference Habicht-Mauche and Eckert2013, Reference Habicht-Mauche and Eckert2019; James et al. Reference James, Eckert and Habicht-Mauche2013). We would like to thank Habicht-Mauche's team of UCSC graduate and undergraduate research assistants, especially Emma Britton, Samantha Linford, and Suzanne Millward; the Friends of Tijeras Pueblo, particularly Kym Campbell, Kath Linn, Bruce Walborn, and the late Lu Kantz; Dr. William D. James; Bruce Tanner, Physical and Biological Sciences Division, UCSC Mineral Preparation Laboratory; Matthew Peeples and Jeffery Ferguson; Marion Coe; Claire Barker; Michael Brescia; the Cibola National Forest, Sandia Ranger District; the staff and volunteers at the Maxwell Museum, especially Dr. David Phillips; the Cultural Heritage Committee of Isleta Pueblo; three anonymous reviewers; and the late Dr. Linda Cordell for all her inspiration, assistance, and support. Funding for the Tijeras Pueblo Ceramics Project was provided by a research grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF 0912154), the UCSC Academic Senate Committee on Research, and the Division of Social Sciences at UCSC.

Data Availability Statement

The NAA data used in this article are available at tDAR id: 458499; DOI:10.6067/XCV8458499. The attribute data generated by the Tijeras Pueblo Ceramics Project are available at tDAR id: 458589; DOI:10.6067/XCV8458589. Excavation materials and records from the University of New Mexico Field Schools in the 1970s are curated at the Maxwell Museum, Albuquerque, New Mexico.