‘Enkido is dead, but I live! Why? Enkido is dead, but I live – but shall die! I am afraid!’Footnote 1 With this anguished cry, the protagonist of Per Nørgård's Gilgamesh (1972) abandons his world, shattered emotionally by the death of his friend, to seek life's hidden meaning. Although Gilgamesh eventually returns home, the principal character in Nørgård's next opera, Siddharta (1979/83), does not. At its conclusion, Siddharta discovers evil and death, and resolves to leave all of his human attachments behind so that he can search for the truths that underlie existence: ‘I was always just a foreign guest – a vagrant and a prattler in that kingdom you built of life's vanished whole.’Footnote 2

All six of Nørgård's operas portray a quest for those hidden truths (Table 1). His worldview was strongly affected by his traumatic experiences as a child during World War II, which undoubtedly prompted his later spiritual explorations.Footnote 3 In this article, I focus on the two operas by Nørgård that situate his spiritual quest within the context of his childhood traumas: Gilgamesh (1972) and Nuit des hommes (1996). After briefly summarising Nørgård's biography and influences for context, I analyse these works as mirror images embodying visions of universal harmony and discord, and spiritual wholeness and disintegration. I then consider Nørgård's use of dialectical polarities and parallels in the two pieces. Joseph Campbell's mythic paradigms and Carl Jung's concept of individuation prove fruitful means by which to place Nørgård's formal strategies within larger frameworks of meaning and structure.Footnote 4

Table 1. Per Nørgård's operas

Born in 1932, Nørgård studied with Vagn Holmboe at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in 1952–5, before spending a year in Paris as a pupil of Nadia Boulanger in 1956–7. Nørgård taught at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in 1960–5, and at The Royal Academy of Music in Aarhus in 1965–94. In recent years, he has received international recognition for his work, including the Wihuri Sibelius Prize (Finland, 2006), the Marie-Josée Kravis Prize for New Music (United States, 2014) and the Ernst von Siemens Music Prize (Germany, 2016). In addition to his operas, Nørgård has written eight symphonies, ten string quartets and many works for percussion and for chorus.

Nørgård's music is characterised by an extraordinary sensitivity to timbre and texture. It often conveys a sense of the movement of sound in space, as in the aptly named percussion solo Waves (1969), for example. As a young Scandinavian composer, Nørgård was deeply influenced by the sounds and structures of Sibelius's music, which have had a lasting impact on his style.Footnote 5 His work on electronic music during the late 1960s also had a formative influence on his compositional thinking.Footnote 6 Like many of his contemporaries, Nørgård took an interest both in the burgeoning early music movement of the 1970s and 1980s – see, for example, Nova Genitura for soprano, violin, recorder, gamba, lute and harpsichord (1975)Footnote 7 – and in Asian music – the opera Der göttliche Tivoli (The Divine Circus) (1982) and percussion works including Gendhing (1980) and A Light Hour (2008). Both sound worlds have expanded the palette of European modernism.

Nørgård's fascination with theosophy and astrology as a means of understanding the universe is comparable to Stockhausen's interest in The Urantia Book, which served as a conceptual source for Donnerstag aus Licht (1977–80).Footnote 8 Many works of both composers embody a turn to esotericism, a search for hidden wisdom and spiritual transcendence. These ideas are common to other composers of Nørgård's generation, including R. Murray Schafer (1933–2021), Philip Glass (b. 1937) and Jonathan Harvey (1939–2012).Footnote 9 Schafer's Ra (part six of Patria) (1982), an eleven-hour musical/theatrical ritual about the death and rebirth of the Egyptian sun god Ra,Footnote 10 shares narrative structures with Gilgamesh, in which Nørgård symbolically depicts the protagonist's death and rebirth. Glass's Akhnaten (1983) portrays both ancient Egyptian rites and the birth of a monotheistic conception of religion. Harvey composed several works that express his interest in Buddhism, including Body Mandala for Orchestra (2006) and the chamber opera Wagner Dream (2007). Atlas (1993), by the slightly younger Meredith Monk (b. 1942), also depicts a search for Eastern wisdom, using as its basis Magic and Mystery in Tibet, a memoir by explorer Alexandra David-Néel (1868–1969) that was popular during the 1960s.Footnote 11 In comparison to these composers, Nørgård's distinctiveness lies in his use of esotericism to explore the disintegration of the human spirit as well as the quest for transcendence.

Mythic paradigms and Jungian archetypes

The Epic of Gilgamesh was compiled during the second millennium BCE. In the mid-nineteenth century, cuneiform clay tablets containing fragments of the epic were discovered in Mesopotamia during archaeological excavations. Scholars have continued the work of reconstructing the text throughout the last century and a half, and many writers, artists and composers have employed the epic as the basis for their own creative efforts.Footnote 12

Per Nørgård wrote Gilgamesh in 1971–2 as a commission from the Stockholm Musikdramatiska Skola (Academy of Music Drama, now the University College of Opera), with Nordisk Musikfond (NOMUS) providing additional financial support. Nørgård wrote his own libretto, employing both Danish and Swedish. Gilgamesh was premiered by Jutland Opera on 4 May 1973 in Aarhus, Denmark. After the first performances, Nørgård revised the score, and the new version was presented in Stockholm on 15 November 1973.Footnote 13

The ancient epic recounts the story of Gilgamesh, king of the city-state of Uruk, who rules despotically over his people. The gods send the hero Enkido to earth to moderate Gilgamesh's tyranny. After the two become friends, they travel together to the Cedar Forest and kill the demon Huwawa.Footnote 14 Gilgamesh then rebuffs the goddess Ishtar's offer of marriage. In revenge, the enraged Ishtar sends the Bull of Heaven to kill Gilgamesh, but Gilgamesh and Enkido kill the Bull. Afterwards, the gods meet in council and decree Enkido's death as punishment for the killing of Huwawa and the Bull. When Enkido dies, Gilgamesh makes a long journey in search of the secret of eternal life, which he learns from the sage Utnapishtim. After failing Utnapishtim's test of wakefulness, Gilgamesh reconciles himself to his mortality and returns to Uruk.

Joseph Campbell's mythic paradigms and Carl Jung's concept of individuation provide powerful tools to interpret the symbolism embedded in Nørgård's opera. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces,Footnote 15 Campbell cites The Epic of Gilgamesh as an example of a universal paradigm that he labels the ‘hero's journey’ or ‘monomyth’.Footnote 16 Campbell's description closely resembles the Gilgamesh story. Like Gilgamesh, Campbell's hero ‘ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder’ and encounters ‘fabulous forces’.Footnote 17 He ‘comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man’.Footnote 18 Similarly, Gilgamesh travels to the end of the world to learn secret knowledge, then returns to Uruk and resumes his duties as king.

Campbell summarises his intellectual model with the cyclic formula ‘separation or departure – initiation – return’.Footnote 19 From Campbell's perspective, the first stage of the Gilgamesh narrative, that of separation or departure,Footnote 20 includes the ‘call to adventure’Footnote 21 and the hero's ‘crossing of the first threshold’Footnote 22 to slay Huwawa. In the second stage, that of initiation, Gilgamesh embarks on the ‘road of trials’.Footnote 23 He confronts the goddess Ishtar, kills the Bull of Heaven, and journeys to the end of the earth to seek the ‘ultimate boon’, the elixir of immortality, to which he is guided by the sage Utnapishtim.Footnote 24 Gilgamesh then reaches the third stage, the ‘hero's return from the mystic realm’Footnote 25 to human society. Although Gilgamesh loses the elixir, a plant with magical properties, during his journey back to Uruk, he reconciles himself to his mortal fate, having ‘[learnt] of everything the sum of wisdom’Footnote 26 during his adventures.

Campbell relates two further concepts to his theory of the ‘hero's journey’. First, the ‘cosmogonic cycle’, which he defines as the ‘mythical image of the world's coming to manifestation and subsequent return into the nonmanifest condition’Footnote 27 – its creation and ultimate destruction. This converges with the ‘hero's journey’ at the moment when the hero transcends the limits of human consciousness and grasps the timeless reality that lies beyond it.Footnote 28 Second, the Jungian concept of individuation: ‘the synthesis of conscious and unconscious elements in the personality’,Footnote 29 accomplished through mastering of the content of ‘archetypes’ that lie within the unconscious.Footnote 30 For Campbell, this provides the ‘hero's journey’ with an additional layer of meaning: the hero withdraws from the world to the psyche, then breaks through to the direct experience and assimilation of ‘the archetypal images’.Footnote 31

Among the archetypes in Jung's individuation process are the shadow, the anima/animus, and the wise old man/woman. Jung defined the ‘personal shadow’ (or ‘individual shadow’) as the subject's dysfunctional personality traits.Footnote 32 He also employed the concept of the ‘collective shadow’, associated with collective evil.Footnote 33 In contrast to the shadow, the anima/animus represents the opposite gender in both its positive and negative manifestations within the human psyche.Footnote 34 Finally, when a person has resolved the inner conflicts produced by the shadow and the anima/animus, a new stage is initiated in which guides or guardian figures appear.Footnote 35

Per Nørgård reconceived the Gilgamesh epic to create a parable about the growth of human consciousness,Footnote 36 fashioning a version of the story that can be construed as a dramatisation of both Campbell's mythic paradigms and the process of individuation.Footnote 37 From a Jungian perspective, Nørgård's retelling of the Gilgamesh narrative is a highly schematic descent into the unconscious. Gilgamesh first clashes with Enkido, who represents his personal shadow. He then slays Huwawa and the Bull of Heaven, who represent the collective shadow,Footnote 38 enacting the hero's battle with a dragon.Footnote 39 The victory over Huwawa leads to Gilgamesh's confrontation with the goddess Ishtar, who represents his negative anima.Footnote 40 The death of Enkido prompts Gilgamesh to embark on the quest that leads to his meeting with the ‘wise old man’, his spiritual guide Utnapishtim. Gilgamesh's journey through the darkness to gain wisdom represents Jung's Nekyia, the ‘descent into the cave’, which Jung describes as the ‘introversion of the conscious mind into the deeper layers of the psyche’.Footnote 41

While the ancient epic begins with a description of the seemingly invincible protagonist, Nørgård begins his portrayal of Gilgamesh with the character's creation by the goddess Aruru. When Gilgamesh makes his entrance, he is as verbally incoherent as an infant, though fully formed physically. Only gradually does he learn to express himself and communicate with others. Nørgård's modification of the Gilgamesh narrative parallels extensions of Jung's theories by the latter's disciples, who applied the concept of individuation to the psychic processes that take place at the beginning of life.Footnote 42 According to Edward F. Edinger, ‘We are born in a state of inflation. In earliest infancy, no ego or consciousness exists … The latent ego is in complete identification with the Self.’Footnote 43 Edinger's analysis neatly describes Nørgård's depiction of Gilgamesh's initial attempts to speak on the second and third days of the opera (discussed below), which are devoted to self-assertion and garbled attempts to pronounce his name. By altering the ancient epic narrative to dramatise Gilgamesh's acquisition of language, Nørgård is able to engage the concept of individuation on a deeper psychological level than would have been possible if he had simply transferred the epic unchanged to the operatic stage.

Re-envisioning the hero's journey: structural polarities and parallels in Nørgård's Gilgamesh

From a schematic perspective, the plot of Gilgamesh is organised around polarities of creation and death, the human and the divine, and self and others (Table 2),Footnote 44 subjects that have preoccupied Nørgård throughout his career. By employing these polarities within the larger context of the hero's voyage of spiritual discovery, Nørgård resolves the dissonance of alienation and death into a cosmic harmony, a scenario that recalls his first opera, Labyrinten (1963).Footnote 45 Nørgård uses the polarities of creation and death to generate the opera's central narrative, Gilgamesh's ‘hero's journey’. On a more intimate level, the polarities of self and others permit the composer to dramatise the stages of Gilgamesh's path to individuation. Mediating between the two levels, Nørgård's depiction of human–divine relationships enables him to portray the cosmic and social disruption created by the protagonist's violation of divine law, and its repair at the opera's conclusion.

Table 2. Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh (1972): narrative structure

While the theme of creation frames the entire opera, the drama pivots on the three confrontations with death that lie at its centre: the battle with Huwawa, Ishtar's attempted seduction and the battle with the Bull of Heaven. Nørgård neatly orders his drama by creating palindromic symmetry between his presentation of the themes of creation, instruction, travel and friendship before and after the three confrontations with death:

Creation: Gods, demons, animals and men; Gilgamesh; Enkido

Instruction: Ishara teaches Enkido

Travel: Enkido's journey to Uruk

Friendship: Gilgamesh and Enkido become friends

Confrontations: Huwawa, Ishtar, Bull of Heaven

Friendship: Enkido's death and Gilgamesh's grief

Travel: Gilgamesh's journey to Utnapishtim

Instruction: Utnapishtim teaches Gilgamesh sacred wisdom

Creation: Creation Symphony; Gilgamesh created anew

In the palindrome's first half, the themes of instruction, travel and friendship define the stages of Enkido's psychic and physical journey from the natural world to the human realm. In the second, they define stages on Gilgamesh's path to individuation, as he journeys from the human realm to seek the divine. The opera's final scenes portray the beginning of a new cycle of creation, in which the harmony of the Universe is restored. Enkido takes his original place in the forest,Footnote 46 while Gilgamesh is reborn ‘on a different plane’Footnote 47 as an enlightened ruler.

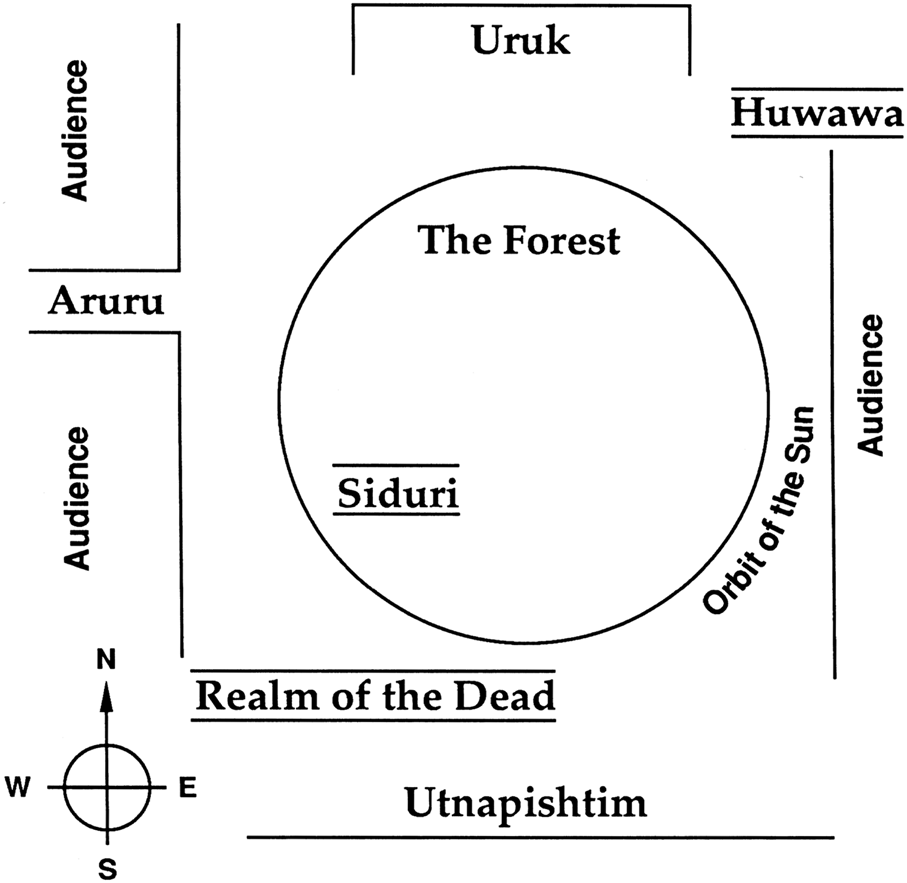

Nørgård expresses the opera's symmetrical structure in its staging. The audience sits to the right and left of the performers, while the conductor moves back and forth between the north and south ‘poles’ of the auditorium, the city of Uruk and the home of Utnapishtim. He fills the role of the sun god Shamash, ‘traveling his cyclic orbit in space once a day’.Footnote 48 Gilgamesh also circles the stage, completing the journey from Uruk to Utnapishtim's home and back. His movements underscore the cyclic paradigm that underlies Nørgård's dramatic conception (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Dramatic diagram for Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh. Footnote 49

In her review of Swedish Opera's 1976 production of Gilgamesh, Eva Redvall noted some of the many dialectical polarities upon which the opera is grounded, discussed the unusual staging requirements and described aspects of the production – including the sets, the costumes and the choreographed movements of the chorus – that highlighted the ancient epic's archaic character (Figure 2):Footnote 50

Per Nørgård's Gilgamesh … deals with the eternal questions of life and death, good and evil, and also with problems of nature and civilisation … Since Gilgamesh demands a special setting, with an arena stage, the crew moved into a big exhibition hall in the Stockholm Museum of Technical Science, where designer Peter Berggren built a stage surrounded by platforms and grandstands … [Director Donya] Feuer focused on the primitive touch and turned the show into something of a rite, led by the high priest Shamash, who was at the same time conductor of the performance … The inhabitants of Uruk wore ritual paint and moved in ceremonial patterns.Footnote 51

Figure 2. Gilgamesh triumphantly raises aloft the severed head of Huwawa, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh (1972), Day 5. The Swedish Opera, Stockholm, 1976. Gilgamesh: Helge Brilioth. Photo: E. M. Rydberg.Footnote 53

Creation and death

Nørgård employs the opera's many structural polarities and parallels to transform the ancient epic from a parable about human mortality to an allegory of human spiritual development. By adding elements to the plot and modifying others to change their symbolic meaning, he builds upon the narrative symmetries already present within the epic to project his didactic message. The most important element in Nørgård's revision of the epic narrative is his handling of the polarities of creation and death.Footnote 52 His emphasis of these polarities underscores the opera's depiction of the ceaseless process of creation, destruction and renewal within the universe – Campbell's ‘cosmogonic cycle’.Footnote 54

Nørgård inserts many creation stories into the plot, as well as incorporating the symbolism of creation. The primacy of this topos within the work is underlined by its subtitle, ‘Opera in Six Days and Seven Nights’, which echoes the book of Genesis. Unlike the ancient epic, the opera begins with the creation of the world and concludes with a second creation story, the physical and spiritual rebirth of the protagonist. Nørgård also modifies the epic narrative by adding Gilgamesh's creation by the Mother Goddess Aruru.Footnote 55 In the epic, Gilgamesh is the adult son of Ninsun, queen of Uruk.

In contrast to plot elements that represent the theme of creation, the opera is punctuated by depictions of death as well as its symbolism: the killing of Huwawa and the Bull of Heaven; the attempted seduction of Gilgamesh by Ishtar; Enkido's death; Gilgamesh's journey in thick darkness to meet Utnapishtim; and Gilgamesh's encounter with the sage, including the week-long slumber that precedes his rebirth. Unlike most of the opera's creation stories, all of these episodes are included in the ancient epic.

While Nørgård begins and ends the opera with the theme of creation, he places the concept of death at its formal centre. Ishtar's attempted seduction of Gilgamesh – her failed effort to lure him to his death – is the work's most disturbing moment.Footnote 56 In recognition of her true character, Gilgamesh calls her ‘Temptress, Witch!’Footnote 57 Ishtar's ominous music expresses the threatening character of her offer of marriage, and her sinister intent is clarified by her violent actions after Gilgamesh rejects her advances. In the epic, Gilgamesh is given compelling reasons for his behaviour. Tzvi Abusch has demonstrated that Ishtar's verbal ambiguity conceals a death warrant: ‘Ishtar's marriage proposal constitutes an offer to Gilgamesh to become a functionary of the netherworld … Our text describes a funeral ritual.’Footnote 58 Abusch comments, ‘Gilgamesh was not deceived … [H]is speech … makes sense only if he is responding to an offer of death.’Footnote 59 After his encounter with Ishtar, Gilgamesh spends the remainder of both the epic and the opera trying to forestall his inevitable death.Footnote 60

Although Gilgamesh's encounter in the epic with Utnapishtim is similarly emblematic of death, Nørgård endows it with a strongly positive symbolic meaning. In the epic, Gilgamesh's hope to transcend human fate is dashed by Utnapishtim's stern advice that he is subject to the same cosmic laws as all men and women.Footnote 61 After the sage guides him to the rejuvenating plant that serves as the hero's ‘ultimate boon’, it is stolen by a snake. Nørgård, however, alters the meaning of Gilgamesh's meeting with Utnapishtim by making it representative not only of death, but of life. For Nørgård, Utnapishtim serves as the archetypal ‘wise old man’ in Jung's schema of individuation. While he hands the physically rejuvenating plant to Gilgamesh (which is quickly stolen, just as in the epic), he also dispenses transformative wisdom.Footnote 62 Nørgård reinterprets Utnapishtim's teaching as a call to a kind of Nietzschean self-overcoming. He interpolates the advice that Gilgamesh should master himself: ‘You should have conquered your world – with insight … found your direction … adjusted its course … grasped your fate and awoken as a New [man].’Footnote 63 Nørgård may have been indebted to a contemporary novel, Guido Bachmann's Gilgamesch (1966), in which a priest tells the protagonist, a young composer, ‘Go on building! Be yourself, become and grow! Climb from step to step … from success to success: from truth to truth all the way to eternal truth.’Footnote 64 Gilgamesh's implicit acceptance of Utnapishtim's teaching is the prerequisite for his rebirth as an enlightened ruler, the polar opposite of the despot who oppresses the people of Uruk in the opera's opening scenes. While the epic can be described as a depiction of Gilgamesh's confrontation with, and acceptance of, the concept of mortality, Nørgård creates a drama focused on the mystery of creation and spiritual renewal.

Nørgård underlines the significance of Utnapishtim's transformative teaching by coupling it with Gilgamesh's abortive attempt to rescue Enkido from the netherworld. Nørgård based the scene loosely on the Sumerian poem ‘Bilgames and the Netherworld’, which predated the Gilgamesh epic and was later incorporated into it as the concluding Tablet XII.Footnote 65 In the poem, Gilgamesh implores the gods Ea and Shamash to bring his servant Enkido back to life after Enkido dies while travelling to the netherworld. In response, the gods permit Enkido's ghost to visit Gilgamesh.

On a superficial level, Nørgård's insertion of Gilgamesh's attempt to rescue Enkido from the netherworldFootnote 66 creates an analogue to the Orpheus myth; he later dramatised the story of Orpheus in the opera Den Uendelige Sang [The Unending Song] (1988). Among works by Nørgård's contemporaries, the second act of Sir Harrison Birtwistle's opera The Mask of Orpheus (1984) provides the closest parallel to Gilgamesh's effort in the opera to free Enkido from the realm of the dead. Birtwistle depicts the trip to the netherworld as an elaborate dream sequence in which Orpheus travels through seventeen arches in order to rescue Eurydice.Footnote 67 Nørgård's dramatic treatment of Gilgamesh's effort to rescue Enkido depicts the protagonist in a negative light, however. Unlike Orpheus, Nørgård's Gilgamesh does not attempt to abide by divine law when he visits the netherworld. He quickly becomes violent, attacking Huwawa and the Bull of Heaven while a chorus of citizens of Uruk exclaims ‘Kill the Bull! Kill Enkido! Kill Huwawa!’ Nørgård juxtaposes this scene with Utnapishtim's exhortations to Gilgamesh to master himself. This contrast of the two actions encapsulates the opera's didactic message: rather than attempting to conquer the external world by force, Gilgamesh (symbolising all of humanity) needs to turn inward – to conquer his [own] world with insight – in order to reach personal fulfilment and create societal harmony.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Nørgård and Birtwistle were not alone in dramatising ancient myths about the mysteries of creation and death. In the music drama Ra, Schafer employed both dramatic and musical techniques that recall Nørgård's depiction of the cycle of death and rebirth in Gilgamesh. Schafer discarded the performer/audience dichotomy in favour of a scenario in which seventy-five participants enact Ra's musical rituals;Footnote 68 similarly, a chorus of citizens, not present in the Gilgamesh epic, accompanies Nørgård's protagonist when he embarks on his journey to enlightenment. In both operas, turning points in the spiritual journey are demarcated by the striking of pitched percussion.Footnote 69

Both Nørgård and Birtwistle add a related concept to the polarity between creation and death: the opposition between light and darkness. Nørgård's work begins with an invocation to the sun god Shamash.Footnote 70 After Gilgamesh's journey through darkness and his prolonged slumber, Aruru creates him anew as the sun rises. By linking the polarities of creation and death, and light and darkness, Nørgård transforms the epic narrative, overlaying ideas reminiscent of the ancient Egyptian religious beliefs about the afterlife that Schafer invokes in Ra.Footnote 71

The human and the divine

Nørgård's minimalist depiction of human–divine relationships is one of his most radical modifications of the Gilgamesh narrative. He limits Gilgamesh's direct contact with the gods to the confrontation with Ishtar and brief appearances by the sun god Shamash. Nørgård omits Shamash's crucial role in the slaying of Huwawa, although the god abruptly appears in order to assist in killing the trombone-playing Bull of Heaven, a scene recalling Michael's slaying of Lucifer's manifestation as a dragon (doubled by a tap-dancing trombone-player) in Stockhausen's later Donnerstag aus Licht (III, 1). In the epic, characters regularly appeal to benevolent deities for protection and counsel. They commune with them directly, through dreams and in religious ceremonies.Footnote 72

While Nørgård curtails Shamash's role in the opera, he endows the dispute between Gilgamesh and Ishtar with far greater import than does the ancient epic.Footnote 73 The women of Uruk seemingly interpret Gilgamesh's rebuke of the goddess as an attack on the rights and privileges of women within the sphere of sexual relations. Such an attack betokens the breakdown of society as a whole. Gilgamesh's effrontery generates such rage among the women of Uruk that they demand his death and that of Enkido, even before he kills the Bull of Heaven. After the Bull is slain, the women ‘turn their backs towards the men’, a gesture reminiscent of Aristophanes's Lysistrata.

The goddess Aruru, Ishtar's polar opposite within the operatic plot, plays only a limited role in the work. She participates in the chorus during Gilgamesh's journey through darkness and his lengthy slumber, and sings a brief, wordless solo in the penultimate scene. Nevertheless, her all-powerful presence hovers over the action. During the opera's early scenes, Aruru creates both Gilgamesh and Enkido. At the opera's conclusion, she creates Gilgamesh anew, bringing both his ‘hero's journey’ and his process of individuation to completion. Aruru's approach to the sleeping Gilgamesh during the Creation Symphony, together with the goddesses Ishtar and Siduri, can be interpreted as a representation of the idea that the process of individuation is essentially a product of the unconscious, rather than a series of choices directed by the conscious mind.Footnote 74

Focus on self and others

Nørgård presents Gilgamesh's great accomplishments as builder and lawgiver as timeless elements of the story that predate his appearance. Rather than focus on the public aspects of Gilgamesh's identity, Nørgård emphasises the story's private, personal element, constructing a polarity between the self and the world that determines the manner in which he develops the operatic plot.Footnote 75 Nørgård's Gilgamesh begins as a solitary, superhuman figure (‘two-thirds god, one-third man’Footnote 76) who considers himself superior to those around him. Through painful experience, he eventually learns to respect and care for others. Gilgamesh's relationship with Enkido is central to his transformation.

Nørgård reconceives the inception of Gilgamesh's friendship with Enkido in order to focus on the protagonist's human relationships. In both epic and opera, the gods create Enkido in order to check Gilgamesh's abuse of power.Footnote 77 In the epic, Enkido wrestles with Gilgamesh in order to prevent the latter from exercising the droit du seigneur.Footnote 78 Nørgård eliminates the physical combat between the two men. Instead, they engage in a verbal battle over their names, its political subtext unstated.

Enkido's death shocks Gilgamesh into empathetic identification with the fate of others. Overcome by grief, Gilgamesh undertakes the long and arduous journey to meet Utnapishtim in order to discover the secret of immortality. In the epic, Gilgamesh travels alone, his reclusiveness motivated by his fear of death.Footnote 79 In the opera, Gilgamesh journeys together with citizens of Uruk, suggesting that the quest for enlightenment has a communal character. Nørgård's stress on Gilgamesh's relations with others during the journey recalls the initial encounter with Enkido.

At the end of the opera, Gilgamesh broadens his empathy for Enkido to achieve a sense of comradeship with his subjects. Gilgamesh's symbolic embrace of all humankind constitutes the triumphant conclusion of the hero's journey. The final circle dance, accompanied by the celestial harmonies of the overtone series, represents a perfected reenactment of the celebration in which the male citizens of Uruk dance around the triumphant Gilgamesh after he slays Huwawa and the Bull of Heaven on Day 5. In that scene, the ecstatic Gilgamesh sings, ‘Who shines among men? Who shines among heroes?’ while the citizens exclaim, ‘Gilgamesh! Enkido!’, accompanied by alternating fifths and clapping reminiscent of Stockhausen's recent Momente (1962–9).Footnote 80 By way of contrast, at the opera's close, Gilgamesh steps into the circle as only primus inter pares. Nørgård's depiction of celestial and human harmony is comparable to Stockhausen's vision at the end of Donnerstag aus Licht, in which Michael sings, ‘I became a Human … to bring celestial music to humans and human music to celestial beings.’Footnote 81

The final scenes of Tippett's The Midsummer Marriage (1955) present a vision of human and divine love comparable to Nørgård's concluding circle dance. Like Nørgård, Tippett employs Jung's concept of individuation as a dramatic tool.Footnote 82 In The Midsummer Marriage, both Mark and Jenifer engage in a voyage of self-discovery (including descent into a cave and an encounter with guardian figures) that resembles Gilgamesh's spiritual awakening over the course of Nørgård's opera.Footnote 83

In broader cultural terms, Nørgård's vision of universal harmony clearly reflects the popular culture of the period, in which he took a serious interest. For example, Nørgård borrowed the title of his orchestral piece Voyage into the Golden Screen (1968) from a song by pop singer Donovan (Donovan Leitch, b. 1946) that opens with the image of the ‘golden garden Bird of Peace’. The stage directions for the opera's concluding dance (Gilgamesh ‘seizes the hands of the surrounding men and smiles at all of them’) recall the song ‘Aquarius’ from the rock musical Hair (1967), which was performed in Copenhagen in 1968:Footnote 84 ‘Harmony and understanding / Sympathy and trust abounding . . . / Mystic crystal revelation / And the mind's true liberation’. The dance also brings to mind another contemporary work, Leonard Bernstein's Mass (1971), with its imperative, ‘Pass the peace!’

Nørgård has described Gilgamesh as ‘a person lacking in self-control, who nevertheless acquired it through experiencing loss – thereby breaking through to a new level of consciousness, that of brotherly love’.Footnote 85 His analysis of the implicit message of the Gilgamesh epic corresponds closely to recent scholarship on the subject. According to Tzvi Abusch, ‘To be a just and effective ruler requires more than just energy and heroism; and Gilgamesh must learn that a just kingship, a caring shepherdship of his people, is a greater good in peacetime than the heroism of the warlord.’Footnote 86

Text and music in Nørgård's Gilgamesh

Nørgård constructs his operatic setting of the ancient Gilgamesh epic by employing mythic images and symbols that interact in changing combinations. He couples names with epithets reminiscent of Homeric poetry, ensuring constant text repetition; two examples are ‘Gilgamesh, eleven cubits tall’Footnote 87 and ‘giant Huwawa’.Footnote 88 Nørgård also creates musical leitmotifs that have symbolic meaning: the ‘Creation music’, the ‘Evening Howl’, the ‘City music’ and the ‘Forest music’.

The opera displays two divergent tendencies. Nørgård begins with simple musical ideas and progresses gradually towards melodic and harmonic complexity. As the opera unfolds, he elaborates on the motifs presented in the opening scenes, underlining the work's structurally processive character. Gilgamesh's solo vocal lines trace a unique trajectory, however. In the second half of the opera, he frequently employs recitative and speech, rather than song.

The central elements of Nørgård's compositional technique in the opera are the melodic ‘infinity series’ and the natural overtone series. In 1959, Nørgård developed the melodic ‘infinity series’, a formula later rationalised by mathematicians, to generate note sequences in a manner related to fractal geometry.Footnote 89 Nørgård has specified that the melodic infinity series is not linked to a particular scale type;Footnote 90 rather, it is rooted in axial symmetry.Footnote 91 Every version of the series is initiated by stepwise motion from a central pitch in both directions. The chromatic infinity series begins with a semitonal unfolding. Nørgård creates diatonic variants of the series by adapting it to the major/minor key system as well as the church modes.Footnote 92 He employs both diatonic and chromatic versions of the series in Gilgamesh.

During the 1960s, Nørgård applied the concept of the infinity series to harmony and rhythm as well as melody. He conceived the natural overtone series and its mirroring undertone or ‘subharmonic’ series (Nørgård's term) as a ‘harmonic infinity system’,Footnote 93 and applied golden section proportions to rhythm.Footnote 94 In Gilgamesh, Nørgård employed all three facets of his technique in a single work for the first time.Footnote 95 He fully integrated his use of these procedures in the following years, most notably in Symphony No. 3 (1972–5).Footnote 96

The creation music and its variants

The music of Gilgamesh is divided between symbolic representations of the natural and the civilised worlds. Nørgård employs the overtone series as the basis of his depiction of nature, and the melodic infinity series to portray human society.Footnote 97 Gilgamesh is unique among his works for the use of the infinity series as a means of dramatic characterisation.Footnote 98

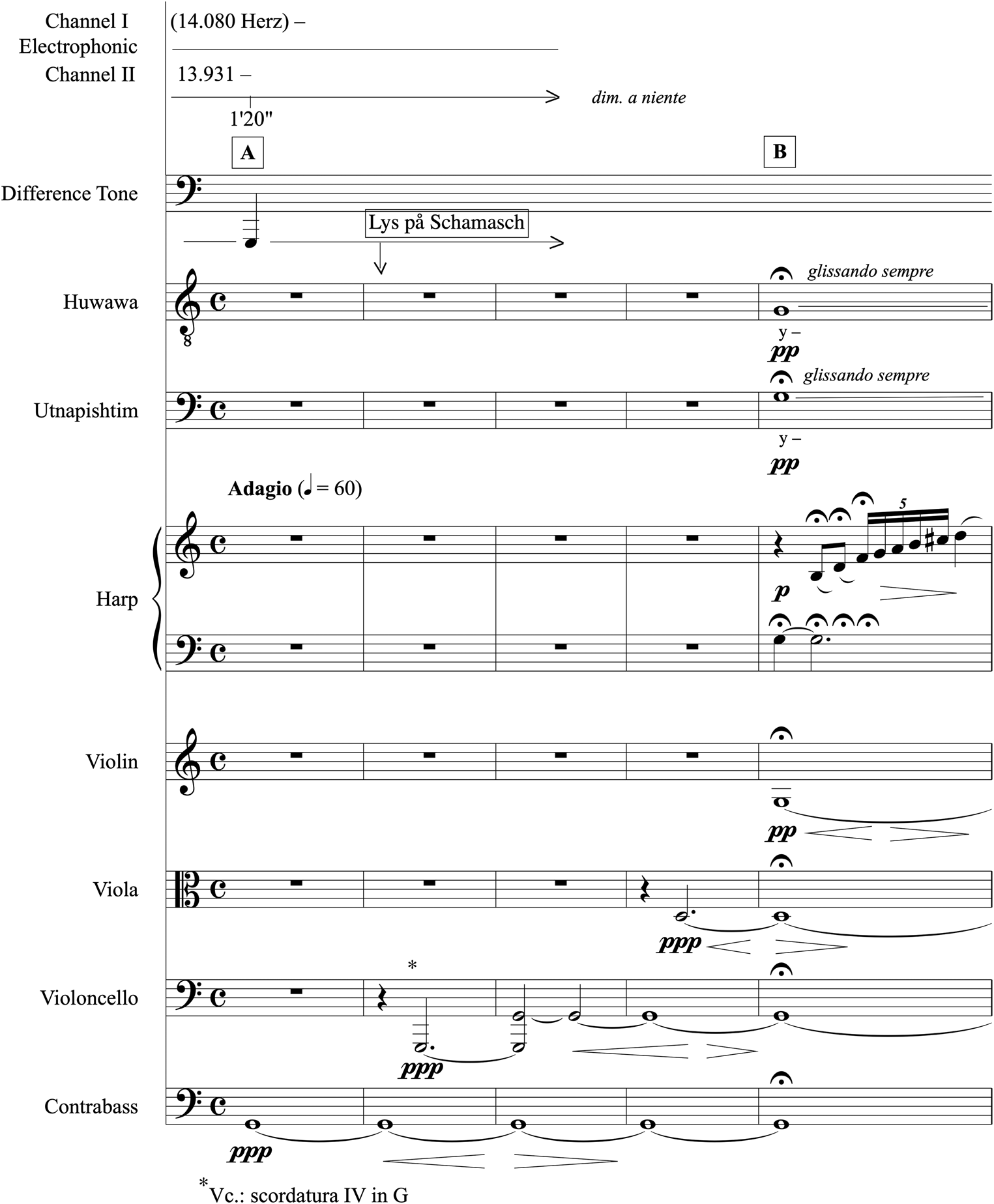

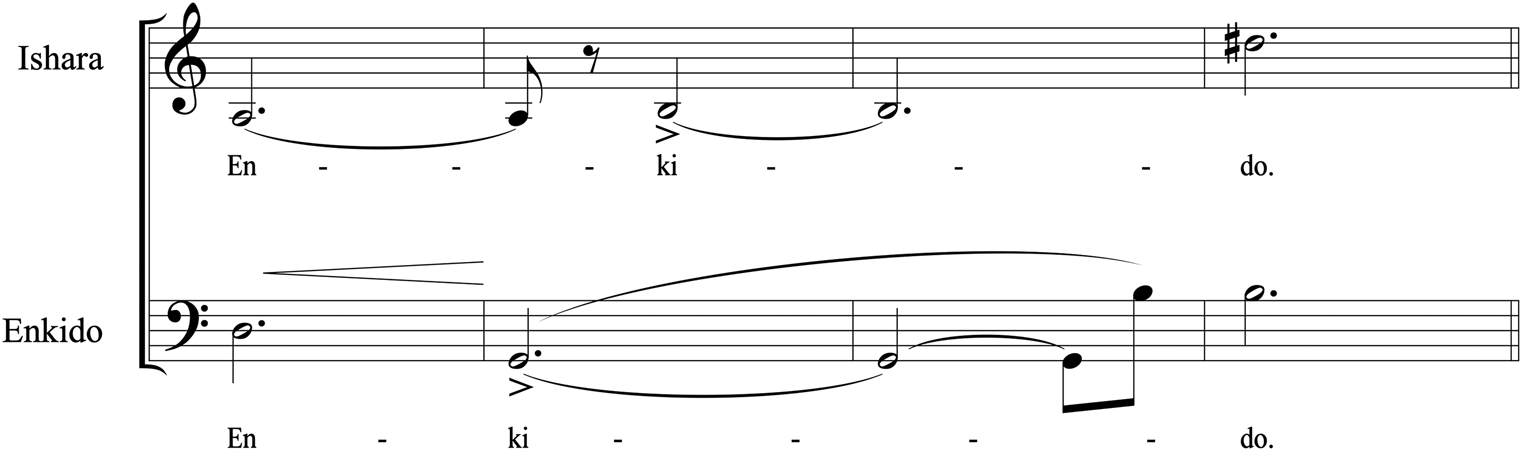

The Creation music provides the musical framework for the drama. At the beginning of the opera, Nørgård uses the overtone series on G, rising from the low bass into the treble register, to symbolise the creation of the world (Example 1).Footnote 99 Enkido is the human representative of the natural world. At his first appearance, he sings the overtone series on G, echoing the Creation music (Example 2). When Gilgamesh first encounters Enkido, their duet begins with triadic patterns based on Enkido's musical leitmotif (Example 3). Enkido's encounter with the sacred prostitute Ishara reflects the consonant character of his music as well. Nørgård begins the Enkido/Ishara scene with tritones, but gradually introduces fifths and thirds between the parts, in a musical tuning of their relationship (Examples 4a and 4b).

Example 1. The unfolding of the harmonic series symbolises the creation of the world, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 1 letters A–B. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 2. Enkido attempts to speak, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 4 letter J, Enkido only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 3. Permutation of the ‘Creation Music’: meeting of Gilgamesh and Enkido, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Day 4 letter A+10. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 4a. Tritones at the beginning of the Ishara–Enkido duet, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 4 letter W−1. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 4b. Consonance in the Ishara–Enkido duet, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 4 letter Z+26. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Utnapishtim's music is the obverse of the Creation music. For his speech about the inevitability of death, Nørgård employs a descending diatonic series, proceeding by thirds, that contrasts with the Creation music's ascending overtone series (Example 5). The pattern of thirds can be conceived as a combination of the overtone and undertone series based on G, the Creation music's fundamental throughout most of the opera. The polarities of the Creation music's ascending patterns and Utnapishtim's descending patterns complement Nørgård's extensive use of textual polarities in Gilgamesh.

Example 5. Utnapishtim teaches Gilgamesh sacred wisdom, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 6 letter A−4, Utnapishtim and wife only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Gilgamesh: between song and speech

Nørgård depicts the growth of human consciousness in both the libretto and music, with the protagonist's own utterances defining the work's central narrative. The circumscribed speech and musical patterns of the opera's other characters serve as foils to his verbal, musical and spiritual evolution. In the opera's first scene (Night 1), Nørgård introduces the ‘City music’, the leitmotif associated with the anonymous mass of Uruk's citizens. It consists of a four-note segment of the diatonic infinity series, C#–D–B–E, continuously rearranged in symmetrical configurations to symbolise their unchanging status (Example 6a).Footnote 100 In contrast, Nørgård uses both diatonic and chromatic versions of the infinity series to portray Gilgamesh, altering the character's musical representation during the course of the opera to depict his spiritual awakening. The weaving pattern associated with Gilgamesh's initial attempt to speak is a diatonic form of the infinity series.Footnote 101 The music conveys Gilgamesh's distinctive individuality from the moment of his first appearance. He initially has great difficulty in verbally articulating his sense of selfhood and babbles, expressing only his self-consciousness as a superior being, the Jungian ‘state of inflation’:Footnote 102 ‘I, I! Gilgamesh, Gish, Gishbil, Gishgibil, Gishbilgamesh, Gishbilgamash – mish’ (Example 6b).

Example 6a. The ‘City music', in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Day 1, beginning, marimbas I and II only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 6b. Gilgamesh attempts to speak, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Day 2 letter E+8, Gilgamesh only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Like Gilgamesh, the operatic Enkido at first expresses himself in a rudimentary manner by repeating his name in uncertain fashion: ‘Är jag Enkido?’ [Am I Enkido?].Footnote 103 In both epic and opera, Enkido is initially portrayed as a kind of primal innocent without human skills.Footnote 104 Although both Gilgamesh and Enkido begin with the primal ‘I’, they soon progress to the first linguistic steps of social differentiation, ‘you’ and ‘we’. Discussing Gilgamesh's initial encounter with Enkido, Jens Brincker cites Jean Gebser's theory of the evolution of human consciousness: ‘Having traversed his own soul … mythical man finds the “other” person … The awakening toward the self proceeds circuitously through the awakening toward the “Thou”; and in the “Thou” the entire world opens up, a previously egoless world of total merging.’Footnote 105 Bo Marschner describes the verbal battle between Gilgamesh and Enkido as a ‘re-creation [Neuschöpfung] of both characters’.Footnote 106

After the two heroes become friends, Nørgård portrays Enkido as a laconic character in order to focus on the development of Gilgamesh's personality. When Enkido senses his approaching death, he is silent. Nørgård's depiction is at variance with the epic, in which Enkido is both voluble and eloquent. He jeers at Ishtar after Gilgamesh kills the Bull of Heaven,Footnote 107 and laments his fate at length as he is dying.Footnote 108 Nørgård's departure from his literary model in reinventing Enkido is underlined by Huwawa's angry assertion in the epic that Enkido ‘know[s] all the arts of speech’.Footnote 109

While Nørgård restricts Enkido's verbal utterances to a minimum, Gilgamesh speaks at length during the latter stages of the opera. He becomes fully coherent only when he abandons song to permit his ‘suffering consciousness’Footnote 110 to express the fear of death. When Gilgamesh addresses Ishtar, he moves between widely spaced, lyrical lines to describe her qualities (‘Lovely Ishtar, Goddess, Beautiful Woman, Temptress, Witch!’) and rapid speech to denounce her treachery (‘You are a castle which crushes the garrison, a pitch that blackens the bearer’).Footnote 111

At the beginning of his initial lament for Enkido, Gilgamesh expresses his distress by singing widely spaced dissonant lines, in which the chromatic infinity series is disguised by the technique of octave displacement (Example 7). In this outburst, Gilgamesh reaches the musical limits of his expression of grief. When he decides to seek out Utnapishtim, Gilgamesh speaks rather than sings as he mourns for Enkido: ‘Should I not fear death? Shall I not – like Enkido – die? … Death is dreadful and inevitable.’ Gilgamesh returns to song, however, when he discusses Utnapishtim's transcendence of death: ‘No, one man searched for life and entered into the company of the gods for eternity. Utnapishtim, behind the sun he lies, man-and-woman’ (Example 8).Footnote 112

Example 7. Gilgamesh: ‘Enkido is dead, but I live! Why?' in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 6+3, Gilgamesh only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 8. Gilgamesh: ‘Utnapishtim, behind the sun he lies, man-and-woman', in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 6 letter B. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Nørgård creates a structural parallelism between Gilgamesh's initial lament for Enkido and the scene in which he expresses his fear of death to Utnapishtim. Just as Gilgamesh speaks of death but sings about Utnapishtim during the earlier scene, Utnapishtim and his wife respond with song to Gilgamesh's recitative and rapid speech.Footnote 113 In the opera's original version, however, Nørgård highlighted the polarity between song and speech by presenting the entire interchange between Gilgamesh and Utnapishtim as spoken dialogue.Footnote 114

Gilgamesh repeatedly laments Enkido's death during the lengthy journey in search of Utnapishtim, the culmination of his ‘road of trials’. He stands apart musically from the chorus, alternately expressing his grief in song, recitative and speech. In one passage, Nørgård employs a descending octatonic motif for Gilgamesh's lament that resembles Ishtar's ominous music in the parameters of pitch, rhythm and contour, linking Ishtar's death-symbolism with Gilgamesh's fear of death (Examples 9a and 9b).Footnote 115

Example 9a. Octatonic motif, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Day 5 letter H, Ishtar only. Text: ‘I love you, Gilgamesh.' Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 9b. Octatonic motif, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 6 letter H−1, Gilgamesh only. Text: ‘Enkido is dead.' Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

For the music of Gilgamesh's companions during the journey, Nørgård adapts and expands ideas borrowed from movement II of Voyage into the Golden Screen for Chamber Orchestra (Examples 10a and 10b), his musical response to Donovan's vision of a journey to a ‘celestial shore’. The alternating diatonic and chromatic patterns are variants of the infinity series. At the beginning of the scene, a chorus of Uruk's citizens sings the chromatic infinity series while describing the impenetrable darkness (Donovan's ‘the forest thick’) through which they travel.Footnote 116 But he uses the diatonic form of the infinity series when the citizens, spirits of the forest and the goddesses Aruru, Siduri and Ishtar call to Gilgamesh, imploring him to return to life and light (Night 6 letters I–M). This use of the diatonic infinity series for the goddesses and spirits of the forest suggests a reweaving of the web of human–divine relationships that had been shattered by the killing of Huwawa and the Bull of Heaven.

Example 10a. Per Nørgård, Voyage into the Golden Screen for Chamber Orchestra (1968), II, letter A. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 10b. Gilgamesh travels under the mountain to meet Utnapishtim, in Per Nørgård, Gilgamesh, Night 6 letter C+4, voices only. Text: ‘The darkness is thick, there is no light, behind me all is black.’ Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

The Creation Symphony portrays Gilgamesh's dream journey of the soul,Footnote 117 the continuation and conclusion of the voyage that began with his journey through the physical world in search of Utnapishtim. Nørgård's use of the infinity series here creates a musical parallel between the two episodes that reinforces the correspondence between their subject matter. At the end of the opera, Nørgård constructs an additional musical symmetry, recalling the work's beginning by employing the Forest music and the Creation music to accompany Aruru's creation of the ‘new’ Gilgamesh. He also shifts the Creation music's fundamental down a fifth from G to C.Footnote 118 Just as the opera opens with the creation of the earth and its inhabitants, Nørgård's use of the Creation music with a new fundamental symbolises a new beginning, not only for Gilgamesh, but for the world.Footnote 119

Nuit des hommes (1996): the challenge of modernity and the hero's failure

Almost twenty-five years after the composition of Gilgamesh, Nørgård returned to its underlying themes in a new opera, Nuit des hommes, but he now expressed a darker vision. In place of the earlier opera's mythical setting, Nørgård substituted the contemporary reality of modern war. Nørgård collaborated on the work's conception with Dutch artist and director Jacob F. Schokking. Nuit des hommes was premiered on 9 September 1996 at the Musikteatret Albertslund, Copenhagen. Nørgård later reused five sections of the opera in his String Quartet No. 8, Natten sænker sig som røg [Night Descending Like Smoke] (1997).

Working together with Schokking, Nørgård constructed the entire libretto from poetry by Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918). Nørgård primarily employed poems from Calligrammes (1918),Footnote 120 which deals with Apollinaire's experiences of World War I. In this way, Nuit des hommes constitutes a selective interpretation of Apollinaire's poetic vision. To create an effective dramatic structure, Nørgård also drew upon Karl Kraus's World War I drama The Last Days of Mankind.Footnote 121 In particular, he used Kraus's satirical depiction of Austrian journalist Alice Schalek as his model for the demonic female war correspondent kAli.Footnote 122

Portraying catastrophe

Nuit des hommes is divided into two acts, preceded by a Préambule and Prologue, followed by an Epilogue, and bisected by an Entr'acte. The first act is a depiction of peacetime, the second of war. At the beginning of the opera, Vilhelm, the archetypal man, and Alice, the archetypal woman, enjoy ordinary pleasures before sensing the threat of the approaching conflict. Within this evolving situation, the characters are transformed (Act I scene 11). They do not, however, morph into completely different people, in a manner comparable to Fred Madison's transformation into Pete Dayton in Olga Neuwirth's opera Lost Highway (2003). Rather, their new identities embody morally debased versions of their original personalities; in Jungian terms, they represent the ‘collective shadow’, manifested in the militarist psychosis that engulfed Europe and produced World War I.

Vilhelm becomes an anonymous soldier, while Alice becomes kAli, a war correspondent. Her new name alludes to the Hindu goddess Kālī, whose persona links cosmic processes of creation and destruction.Footnote 123 Nørgård provides Alice with this secondary appellation to indicate the world-shattering significance of World War I, just as John Adams quotes the Bhagavad Gita in Doctor Atomic (2005) to convey the epochal nature of the invention of the atom bomb.Footnote 124 Significantly, Alice/kAli's given name is identical to that of journalist Alice Schalek, while Vilhelm's name echoes Apollinaire's legal name of Wilhelm Apollinaris de Kostrowitzky.Footnote 125 At the end of Act II, the characters reassume their original identities, but both have been permanently traumatised by their wartime experiences.Footnote 126 During the composition of Nuit des hommes, Nørgård described the nature of the operatic characters: ‘[I]n the opera it isn't simply “Stupid man, suffering woman”. The woman is also partly responsible: both are ambiguous … So we have [Vilhelm] and Alice: real people, not just mouthpieces for Apollinaire's poems.’Footnote 127

While Gilgamesh embodies a successful realisation of the hero's journey, Nuit des hommes represents its antithesis, the hero's journey aborted. At the end of the opera, the characters become directionless wayfarers in a hostile world. Similarly, Nuit des hommes embodies Campbell's cosmogonic cycle, but in its maleficent aspect.Footnote 128 The operatic narrative focuses on destruction and dissolution rather than creation and transcendence. By the work's conclusion, the ‘harmony of the universe’ has been shattered so thoroughly that a new equilibrium is unreachable. Apollinaire's poetry expresses the ideology of Futurism, in which violent processes of creation and destruction are intertwined.Footnote 129 They generate technological progress, but moral and societal chaos: ‘Don't weep for the horrors of war / Before the war we had only the surface / Of the earth and the seas / After it we'll have the depths / Subterranean and aerial space / Masters of the helm.’Footnote 130

In his 1999 Aldeburgh lecture, Nørgård elaborated on the underlying premise of Nuit des hommes:

[C]atastrophic interruptions, in the face of all known cultural development, occurred then [around 1914], and at the same time a flood of new ideas developed: destructive–constructive, disrespectful, awe-inspiring, and world-remodeling scientific revolutions, such as Einstein's and Bohr's … [T]o regard a new departure such as this as a challenge to humanity that requires many centuries to answer and master is inevitable.Footnote 131

Nørgård has labelled Nuit des hommes an ‘opera(torio)’, acknowledging that the work lacks a conventional plot. As in Gilgamesh, the composer carefully calibrates all aspects of the music and its staging to serve his ideological vision. In Nuit des hommes, however, he treats his characters with a much higher degree of abstraction. Their relations are strictly premised on the necessity of articulating the symbolism of each scene, and they often seem to exist in parallel universes. Reviewing the opera's 2014 German production, critic Ute Grundmann described Vilhelm and Alice as ‘simultaneously prototypes, proxies’.Footnote 132 According to Nørgård, ‘[t]he opera portrays [the characters’] interaction as a kind of intensity shared in their common search for the limits of their experience’.Footnote 133 The spare and abstract set design of the original production included graphics projected above and behind the performers, who were positioned at opposite ends of the stage throughout much of the opera (Figure 3).Footnote 134

Figure 3. Vilhelm and Alice express common sentiments in isolation, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes (1996), Act I scene 10, ‘La douce nuit lunaire' [The sweet moonlit night], excerpts from the first four performances at Albertslund Music Theatre, September 1996, vimeo.com/49189809. © 1996 Bent Ryberg/Holland House.

All of the early performances of Nuit des hommes employed Schokking's staging, including the 1996 world premiere in Copenhagen, and the UK and German premieres in 2000.Footnote 135 When the opera was restaged in Germany in 2014, however, the director, Kay Kuntze, placed it within an ostensibly more realistic but highly stylised setting. He paradoxically positioned a work about the immediate pre-World War I period and the war itself within the context of post-World War I German culture.Footnote 136 Kuntze set the opening and closing scenes of Nuit des hommes in a military hospital, while treating the relationship between the characters in a manner reminiscent of Brecht and Weill (Figures 4 and 5).Footnote 137 At the opera's beginning, Alice removed the bandage that covered Vilhelm's head. Insofar as the two acts of Nuit des hommes contrast the characters’ pre-war naïveté and their later disillusionment, Kuntze's staging undercut the work's inherent dramatic logic.

Figure 4. Vilhelm and Alice look at the red wine, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes (1996), Act I scene 1, ‘Le repas’ [The meal]. Theater und Philharmonie Thüringen, Gera, conducted by Takahiro Nagasaki, directed by Kay Kuntze (2014). Photo: Stephan Walzl. https://www.ioco.de/2014/07/18/gera-theater-und-philharmonie-thueringen-nur-noch-eine-auffuehrung-nuit-des-hommes-20-07-2014/.

Figure 5. Vilhelm and Alice embrace, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes (1996), Act I scene 8, ‘O portes de ton corps' [O gates of your body]: ‘I dream of having you night and day in my arms.’ Theater und Philharmonie Thüringen, Gera, conducted by Takahiro Nagasaki, directed by Kay Kuntze (2014). https://www.ioco.de/2014/07/18/gera-theater-und-philharmonie-thueringen-nur-noch-eine-auffuehrung-nuit-des-hommes-20-07-2014/.

Despite Nørgård's assertions about the formal singularity of Nuit des hommes, it has antecedents in works by his contemporaries, such as Nono's opera Intolleranza 1960 (1961) and Kobo Abe's novel The Woman in the Dunes (1962), later adapted as a film by Hiroshi Teshigahara with a score by Toru Takemitsu (1964). Intolleranza 1960, like Nuit des hommes, is a drama about a ‘Man’ and a ‘Woman’, the male Emigrant and his female Comrade. According to Michael Hall, ‘Structurally [Intolleranza] replaces narrative with a series of episodes that take the worker and his female companion from one example of intolerance to the next … [A]ll attention is focused on the situations in which they find themselves.’Footnote 138 Similarly, Abe's novel and Teshigahara's film depict the developing relationship between a man and a woman who remain nameless throughout their lengthy encounter. Nono presents a partisan political statement about contemporary events, while Abe offers a vision of the limits of human autonomy heavily laden with symbolism.Footnote 139 In contrast, Nørgård offers an idiosyncratic theosophical interpretation of the world's ills. He does not, however, present his perspective as a quietist evasion of political action. Rather, he rejects purely materialist explanations in order to give what he perceives as equal importance to both the psychic and physical aspects of human existence.

Peter Maxwell Davies's opera Taverner, op. 45 (1970), displays structural resemblances to Nuit des hommes that differ in kind from those in Intolleranza 1960 and Woman in the Dunes. Both Davies and Nørgård divide their operas into two mirroring acts. In each work, positive images in the first act are linked to negative images in the second. Davies begins with the fictional trial for heresy of the sixteenth-century English composer John Taverner (c.1490–1545). In Act II, Taverner embodies all of the intolerant traits of those who had previously persecuted him.Footnote 140 At the end of the first act, Davies depicts Taverner's spiritual disintegration, picturing the composer's soul transformed into ‘a coal-black raven with shining red eyes’ (Act I scene 4). Like Davies, Nørgård places the turning point of his opera at the end of Act I (Act I scene 11), when Vilhelm and Alice imitate the sounds of cows and sheep to symbolise their own spiritual disintegration and dehumanisation.Footnote 141 In Act II of Nørgård's opera, the Soldier and kAli represent morally debased versions of Vilhelm and Alice, in parallel with Taverner's moral debasement in Act II of Davies's opera.

The soundscape of modern war

Nørgård's portrayal of war in Nuit des hommes embodies his visceral response to a formative experience in his early life, his ‘end of innocence’. In 1945, an RAF bomber crashed into a school building near his home: ‘I remember the German soldiers arriving, the bombings. A girls’ school beside my own school was completely destroyed. For many years I would tremble every time I heard an airplane.’Footnote 142

Nørgård employs electronics as well as instrumental and choral techniques to evoke the soundscape of war. In the Préambule, he attempts to recreate the sound world of World War I, using slow electronic glissandi that recall Luigi Russolo's Futurist instruments, the intonarumori.Footnote 143 Nørgård's musical language is simultaneously indebted to composers such as Xenakis and Penderecki who attempted to capture the sounds of World War II during the 1950s and 1960s. His desire to imitate the sounds of war is characteristic of composers who experienced its horrors. Nouritza Matossian notes,

Everyone had recollections, images, experiences and impressions involving the different senses, but especially recollections of extraordinary sounds heard during air raids, sirens, explosions, bombing … The war had accustomed them to a sound world which had never seemed possible before … This assimilation took many forms, it explains why, for instance, musique concrète was so quickly accepted by this generation as a perfectly natural extension of the sound continuum they had perceived.Footnote 144

When he composed Nuit des hommes, Nørgård recalled ‘the glissando motifs of the sirens and the low, rumbling bass-note rhythms of the aircraft’.Footnote 145 In the Entr'acte, he imitates the rumbling, rushing sound of airplanes. Act II's first and third scenes include loud, explosive sounds, high-pitched whistling sounds, and sounds like breaking glass. The sound of a wailing siren underlies the action of Act II scene 4. Nørgård also employs vocal and string glissandi, buzzing strings and non-synchronised choral shouting.

The two episodes of choral shouting in Act II scene 1 (‘Méditation coupée’) symbolise both the firing of weapons and the onslaught of modern ideas and technologies: ‘Afterward we will take hold of all joys: Women, Games, Factories, Business, Industry, Agriculture, Metal, Fire, Crystal, Speed.’Footnote 146 Before each episode of choral shouting, kAli exclaims, ‘On tire!’ [they are shooting], underlining the link between societal transformation and war. Just as Nørgård's evolving musical processes in Gilgamesh reflect the opera's ultimately hopeful message, the threatening soundscape of Nuit des hommes expresses existential despair in the face of a frightening and incomprehensible new world.

Conceptual polarities in Nuit des hommes

Nørgård structures Nuit des hommes through a network of conceptual polarities comparable to those that undergird Gilgamesh. As in the earlier work, Nørgård employs these polarities to develop the plot within the larger context of the hero's quest. The most important polarity in Nuit des hommes is the contrast between peacetime and war. All of the others are subservient to this primary division within the narrative. They include light and darkness; sensory oppositions, including seeing and hearing, and sight and blindness; human and subhuman; physical love and war; and birth and death. While Nørgård uses parallelisms in Gilgamesh to create palindromic symmetry between the plot's two halves, he arranges the polarities of Nuit des hommes so that the second act becomes the conceptual inverse of the first (Table 3).

Table 3. Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes (1996): narrative structure

The brilliant sunlight of the opera's first act is juxtaposed with the darkness of its second, in which the only lights are exploding rockets. Similarly, birds are transformed into bullets, and sight is replaced by blindness. The hero's journey and its triumphant conclusion are replaced by the atomisation of the damned.

Light and darkness

In Gilgamesh, Nørgård employs the polarity of light and darkness, the sun and its absence, to depict the cycle of life, death and rebirth. In Nuit des hommes, Nørgård again employs these polarities, but in a way that negates their symbolic meaning in the earlier opera. He frames the action of Nuit des hommes with images of the dawn of day. In the Prologue, he employs an abbreviated version of Apollinaire's poem ‘Aurore d'hiver’ [Winter Dawn] to present a seemingly optimistic vision: ‘Adolescent dawn who dreams of the sun … Dawn dreams of the golden sun.’Footnote 147 The dark timbre and ominous character of the music belie the words, however. In the Epilogue, Nørgård presents the poem in full, clarifying its meaning. The hopeful dawn gives way to a cold winter sun: ‘Adolescent dawn who dreams of the sun … A winter sun without bright flames.’Footnote 148 Apollinaire's bleak image of a ‘cold winter sun’ inverts the symbolism of Gilgamesh's concluding scene, the beginning of a harmonious new era, bathed in sunlight.

Nørgård links the characters’ gradual loss of illusions to images of darkness. At the end of Act I (scene 12, ‘La nuit descend’) Vilhelm and Alice sing ‘Night descends without a smile’.Footnote 149 Again, Nørgård reverses the symbolism of Gilgamesh, in which the impenetrable darkness of the pathway through the mountain during the protagonist's journey to meet Utnapishtim is the prelude to spiritual enlightenment.

The opera's title, Nuit des hommes [Night of Men], refers to the second act's frequent associations between night and war. Scenes 1 and 3 present the ironic image of the ‘lovely night’, in which rockets light up the sky.Footnote 150 In scenes 3 and 4, Apollinaire's text describes the ‘night of men only’ as the ‘violent night’ (‘nuit violente’). In the act's final scene (II, 5, ‘Du coton dans les oreilles’), Nørgård offers the image of a desolate moonlit battlefield that contrasts with the depictions of bright sunlight at the beginning of Act I.

Sensory oppositions

In addition to the polarity between light and darkness, Nørgård employs sensory oppositions between seeing and hearing, and sight and blindness. In Act I, he focuses on the theme of sight, primarily the sight of beautiful things, both Bonnard-like domestic scenes and the body of the beloved. In Act II, kAli and the Soldier repeatedly listen (‘écoute!’) to perceive the firing of weapons (II, 1, ‘Méditation coupée’). At the end of the opera, Nørgård again brings back the directive ‘écoute’ (II, 5, ‘Du coton dans les oreilles’) in connection with the sound of gently falling rain. The two characters sing of soldiers, blinded by poison gas attacks (‘blind soldiers in agony, lost … under the liquid moon of Flanders’),Footnote 151 who wander aimlessly through the battlefield. While Gilgamesh ‘finds [his] direction’ and ‘grasps [his] fate’, the blind soldiers symbolise twentieth-century humanity's loss of the beliefs and values that provide life with purpose and meaning.

Human and subhuman

Nuit des hommes presents a symbolic continuum from human to subhuman, produced by the corrosive effects of war. At the beginning, Vilhelm and Alice display aggressive sentiments that lead quickly to the corruption of human feeling. Like the new-born Gilgamesh, both characters arrogantly aspire to divine status. In ‘L'homme dieu!’ they sing ‘And the coming god was made flesh in me’,Footnote 152 as Vilhelm dons a military uniform. Nørgård quickly disabuses his listeners about the characters’ sense of invincibility. He juxtaposes ‘L'homme dieu!’ with a textless scene, ‘L'homme animal’ (I, 5), the title of which suggests that the characters’ hubris leads to the debasement of their personalities. Nørgård connects the symbolism of the title ‘L'homme animal’ to militarism by extending the scene's boisterous music through the following scene, ‘La musique militaire’ (I, 6). Later in Act I, the characters imitate animal sounds as they undergo metamorphosis to their new personae as the Soldier and kAli. Their descent into spiritual degradation and animality – the loss of selfhood symbolised by Vilhelm's transformation into an anonymous ‘Soldier’ – constitutes the antithesis of Gilgamesh's rebirth. The word ‘amour’ is fragmented and permuted as both ‘mou’ [moo] and ‘meh’ [baa].Footnote 153 In the opera's initial production, Vilhelm's plight was dramatised by having him crawl along the stage (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Vilhelm is dehumanised, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes (1996), Act I scene 12, ‘La nuit descend' [Night falls], excerpts from the first four performances at Albertslund Music Theatre, September 1996, vimeo.com/49189809. © 1996 Bent Ryberg/Holland House.

Love and war

Nørgård also illustrates the degradation of the human spirit by creating a polarity between positive and negative sexual images. He creates symmetry between the two acts of Nuit des hommes by employing Apollinaire's transformation of images of sexual desire and physical love into images of war. Nørgård places a graphic love poem, ‘O portes de ton corps’ [O gates of your body], at the centre of Act I (I, 8). In Act II (II, 2), Apollinaire's poem ‘La tranchée’ [the trench] provides a grotesque reinterpretation of the meaning of the earlier scene: ‘Come with me, youth, into my sex / longer than the longest snake.’Footnote 154 The anthropomorphised trench serves a role akin to that of Ishtar in Gilgamesh. According to Sarah Montin, ‘The rare overt sexualisations of the space of war (the earth, the ground, the trench) [in the literature of World War I] always portray fearsome feminine sexuality and perverted fecundity.’Footnote 155

Nørgård extends the sexual metaphor in Act II scene 3, with the Soldier's exclamation ‘Je désire’, derived from Apollinaire's poem ‘Désir’, about a French attack on the German lines in September 1915.Footnote 156 He reinterprets the concept of male sexual desire as a lust for killing and conquest (Example 11a). Nørgård employs a motif that he had previously used in Act I to portray the romantic love of Vilhelm and Alice (Example 11b), creating musical as well as verbal symmetry with the first half of the opera. The exclamation ‘Je désire’ is repeated throughout Act II scene 3, as a refrain within the two characters’ celebration of the grotesque beauty of war. In addition, Nørgård employs Apollinaire's imitation of automatic gunfire, ‘le tac tac tac monotone et bref’, to evoke the symbolic association of the male sex act with the firing of weapons (Example 12).

Example 11a. Desire for conquest, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes, Act II scene 3, ‘Pléthore’, bb. 1–2, Soldier only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 11b. Romantic love, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes, Act I scene 10, ‘Voyage’, b. 64, Alice only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 12. Automatic gunfire, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes, Act II scene 3, ‘Pléthore’, bb. 42–4, Soldier only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Nørgård reinforces Apollinaire's military metaphors by employing waltz rhythms to link love and war. In the opera's first scene, he interrupts the lyrical vocal lines with a purely instrumental passage, marked ‘Wie ein Mächt'ger Walzer’ [like a powerful waltzer] in the score (Example 13). He reuses the waltz motif in parodic form in Act I scene 6, ‘La musique militaire’. He adds bongos and tom-toms, both to underline the warlike associations of the poetry and to link the dance to post-World War I European modernism, which borrowed from vernacular musics of the Americas as well as from African art and music.Footnote 157 In Act II scene 3, he restates this version of the motif while depicting a battle, accompanied by the text ‘Nuit violente et violette et sombre’ [Violent night violet and dark] (Example 14).

Example 13. ‘Wie ein mächt'ger Walzer', in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes, Act I scene 1, ‘Le repas’, bb. 46–50. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Example 14. Parodic form of the waltz motif, in Per Nørgård, Nuit des hommes, Act II scene 3, ‘Pléthore’, bb. 83–7, voice and strings only. Published by Edition Wilhelm Hansen AS, Copenhagen.

Birth and death

Nørgård inverts the meaning of birth and death, with birth portrayed as sterile and death as the source of life. In the Epilogue, he uses the repeated references to death in Apollinaire's ‘Aurore d'hiver’ to underline his polemical message about the spiritual imbalance that governs our chaotic age: ‘les cieux morts’ [dead skies], ‘sans vie’ [without life], ‘l'aurore joyeuse … meurt’ [the joyful dawn dies]. The opera concludes with the jarring image of a ‘stillborn’ sun (‘un soleil mort-né’), in which birth and death are fused.Footnote 158

In the climactic battle scene (II, 4), Nørgård presents Apollinaire's apocalyptic female image of the ‘violent night’ of war,Footnote 159 depicted as a woman in labour: ‘Night screaming like a woman giving birth’.Footnote 160 By using microtones and electronics, Nørgård heightens the effect of Apollinaire's disturbing language in a grotesque reconception of Gilgamesh's journey through the mountain in search of Utnapishtim. Apollinaire's vision of mass death and cosmic rebirth – the inception of a new cosmogonic cycle – counterbalances masculine images in earlier scenes that convey Futurist ideas about the onset of a new era of technological progress.Footnote 161 By employing Apollinaire's vivid metaphors, Nørgård symbolically portrays the traumatic beginning of a new age for humankind.

Gilgamesh and Nuit des hommes: variations on a theme

In Nuit des hommes, Nørgård reimagines Gilgamesh's journey in darkness to enlightenment as Apollinaire's night of war and destruction, ‘screaming like a woman giving birth’. He similarly reimagines the bright morning at Gilgamesh's conclusion as a second grotesque birth image, the ‘still-born sun’. At the opera's midpoint, Nørgård links the degradation of the characters to sub-human status and their presentation as ‘new’, diminished personalities. Here again, Nuit des hommes offers a scenario that inverts the terms of Gilgamesh's saga of spiritual awakening.

Gilgamesh is the central figure in a rigidly hierarchical society. He first abandons, then resumes his divinely appointed role, ‘conquer[ing] his world with insight’ and ‘find[ing] his direction’.Footnote 162 In contrast, Vilhelm and Alice begin Nuit des hommes in a fast-disappearing world of familiar certainties and are plunged into a whirlwind of incomprehensible societal transformation. Nørgård symbolises their cognitive difficulties by rendering the choral ‘insights’ of Act II scene 1 as a near-unintelligible babble, effectively conveying the idea that change occurs so quickly and bewilderingly that it cannot be grasped by either the ear or the mind. Similarly, the blinded soldiers of Act II scene 5 are unable to ‘find their direction’. Instead, they move haphazardly through moonlit battlefields.

Under the sign of kAli, the journalist/goddess, Vilhelm's journey through the experience of war becomes a parody of the hero's trials and eventual triumph. Vilhelm's plight is expressed through his new anonymity as the ‘Soldier’. Deprived of his sense of selfhood, he is incapable of enacting the process of individuation that lies at the core of the hero's journey. The Soldier is psychologically destroyed by the trials that he undergoes, which are comparable to those that purify and elevate Gilgamesh's personality. While Gilgamesh is able to resist the overtures of the threatening Ishtar, kAli/Kālī – kālarātri, the ‘night of death’ – dominates the second act of Nuit des hommes without challenge.

In Nuit des hommes, Nørgård limns a vivid metaphorical portrait of our disordered age. The opera's real tragedy is not, however, the confusion attending radical change, nor the mass destruction caused by modern warfare, but society's moral failure. Vilhelm and Alice begin their spiritual decline by focusing selfishly on themselves and asserting a sense of transcendent personal power. In contrast, Gilgamesh first disrupts the social order by disregarding the needs of his subjects, but eventually completes his successful traversal of the hero's journey by embracing his fellow men and women as equals.

Not long after Gilgamesh's premiere, Nørgård asserted, ‘[a]ll “unmusicality” must be banished; sensitivity towards each other's nature is a revolutionary duty’.Footnote 163 Nørgård's Levinasian ethics of the encounter with the OtherFootnote 164 recalls the conclusion of Gilgamesh as well as the Ishara–Enkido and Enkido–Gilgamesh duets, both of which musically portray a gradual process of ‘attunement’ between characters.Footnote 165 More recently, a chastened Nørgård reiterated his belief in the fundamentally harmonious nature of the universe while bemoaning human cruelty and intolerance in comments about the cantata Lygtemænd i Byen [Will-o’-the-Wisps in Town] (2004/05).Footnote 166 Will-o’-the-Wisps in Town includes a brief musical allusion to Vilhelm and Alice's moral disintegration in Nuit des hommes.Footnote 167

Nørgård's artistic journey has taken us full circle. The social critique of Nuit des hommes can be related directly to his use of the overtone series in Gilgamesh to illustrate both spiritual and physical harmony. Ultimately, for Per Nørgård, to heal humanity's dysfunction requires nothing less than the tuning of the world.