Background

Building on a scoping review framework developed by Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) and expanded upon by Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010), a scoping literature review was performed to examine what is known from existing primary studies, literature reviews and descriptive accounts about: the structures and processes required to build successful collaborations between primary care (PC) and public health (PH); outcomes of collaborations between PH and PC; and markers of successful PC and PH collaboration. This paper illustrates the five stages used to conduct a scoping literature review to highlight challenges encountered and ‘lessons learned’ including the use of enabling technologies to support each phase. This review applied an integrated knowledge translation approach involving a large interprofessional, geographically distributed team comprised of researchers and decision-makers. Recommendations are therefore also made for managing the challenges with a diverse team. In particular, we discuss the use of various technologies that facilitated knowledge development and exchange, including: Reference Manager 10® (The Thomson Corporation, 2009) and NVivo 8 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2008) qualitative analysis software to facilitate data management, analysis and report preparation; web conferencing – Elluminate Live! (Blackboard, 2010) – to support team communication; and a government-supported provincial PH portal – eHealthOntario.ca (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care, 2008) – to support team communication as well as secure storage and retrieval of documents used and developed in the review. Results of the review itself are found in an accompanying paper (Martin-Misener et al., Reference Martin-Misener, Valaitis, Wong, MacDonald, Meagher-Stewart, Kaczorowski, O'Mara, Savage and Austin2011). This methods paper describes the detailed processes used to conduct the review and reports on the yield at each stage to enable readers to assess the methodological rigor of the study and applicability of the processes for other research.

Why collaborate?

In 1978, the Alma Ata Declaration identified primary health care as a strategy to reach the goal of ‘Health for All by the Year 2000’ (World Health Organization, 1978). Primary health care principles were built on the foundational concepts of access to health care, social justice and equity. In 2008, the World Health Organization released the seminal report ‘Primary Health Care Now More than Ever’, which further challenged us to consider ways to improve healthcare systems (World Health Organization, 2008). The report sets out four reforms ‘that reflect a convergence between the values of primary health care, the expectations of citizens and the common health performance challenges that cut across all contexts’ (p. ix). Most relevant for this paper, the report calls for public policy reforms that support healthier communities through integrating PH actions with PC and pursuing healthy public policies. Frenk (Reference Frenk2009) argues that ‘to strengthen health systems and to achieve integrated care, we need integration between interventions, especially when a collection of distinct vertical programmes exists, and integration of primary health care with the rest of the health system’. Further, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) identified integrating PC and PH as a priority for strengthening the PH system (CIHR, 2003) and as an overall research priority (CIHR, 2007).

To date, health systems have largely failed to integrate individual and PH perspectives to improve people's health (van Weel et al., Reference van Weel, De Maeseneer and Roberts2008; van Weel and De Maeseneer, Reference van Weel and De Maeseneer2010). Worldwide, health systems are struggling to determine the best contexts and strategies for PC and PH to collaborate, as many nations organize these systems into silos. Particularly in PC, research has focused on interdisciplinary team collaboration (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Lewis, Ellis, Beckhoff, Stewart, Freeman and Kasperski2010; McPherson and McGibbon, Reference McPherson and McGibbon2010) rather than interorganizational collaboration. Some important work on this concept has been carried out (Lasker et al., Reference Lasker, Abramson and Freedman1998; Reference Lasker, Weiss and Miller2001; Sicotte et al., Reference Sicotte, D'Amour and Moreault2002; D'Amour et al., Reference D'Amour, Goulet, Labadie, Martin-Rodriguez and Pineault2008), but there has been no comprehensive synthesis of literature on PC and PH collaborations.

Scoping literature reviews

Scoping studies comprehensively review available literature to ‘map’ critical ideas within a topic guided by one or more general research questions (Levac et al., Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010). Their use is growing across many disciplines and involves mapping literature, concepts and policy (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Allen, Peckham and Goodwin2008). The notion of mapping can refer to the source of literature (ie, country of origin) as well as the exploration of the breadth of the topic of interest. In our scoping literature review, we aimed to get a sense of the breadth of information on the topic guided by specific research questions and to map the origin of the literature.

The scoping literature review approach differs from more commonly used systematic literature reviews that aim to answer more focused questions and also assess the methodological quality of studies where potential biases and limitations in study design are examined. Compared to systematic reviews, exclusion and inclusion criteria are determined based on relevance rather than the quality of studies. Similar to systematic reviews, scoping reviews use rigorous methods that seek all literature relevant to the topic being studied. Methods need to be comprehensive and transparent, so as to be replicable. Rumrill et al. (Reference Rumrill, Fitzgerald and Merchant2010) differentiate between scoping literature reviews and other types of reviews and note that the former tend to include a mix of qualitative and quantitative studies, as well as a wide range of non-research materials. They argue that these reviews can be exploratory examining the range and nature of a particular topic or they can be used to disseminate research findings on particular research questions and identify gaps in research. Anderson et al. (Reference Anderson, Allen, Peckham and Goodwin2008) conducted an analysis of scoping studies commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organization (NIHR SDO) in the United Kingdom, and found that 24 studies were conducted over six years. Among them were studies examining relationships between organizations, PH and outpatient services, as well as organizational factors and performance.

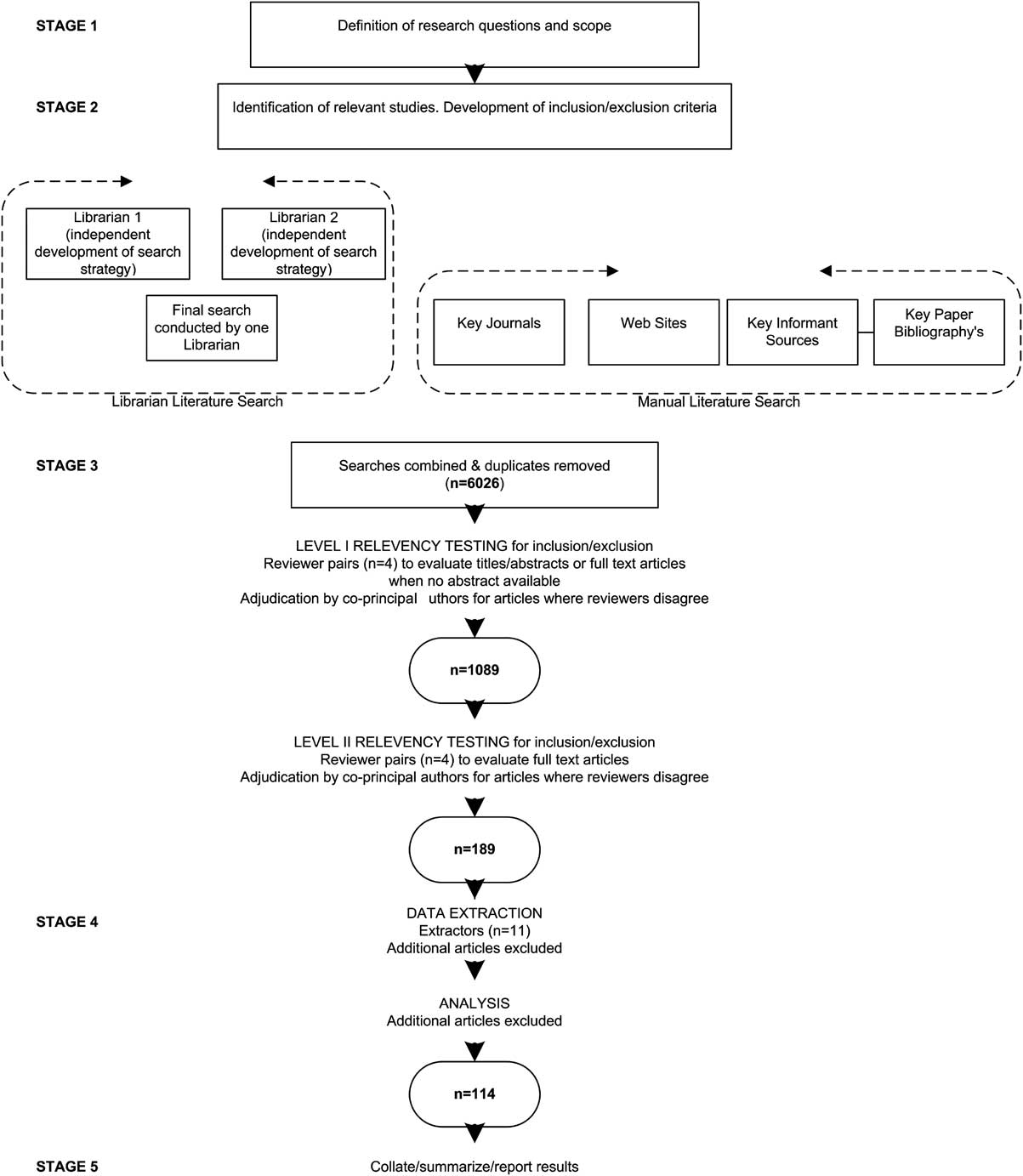

Arksey and O'Malley (Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005) describe a five-stage framework for conducting a scoping review that was used in the current study (Figure 1). In a scoping review, papers are included regardless of their research design and methodological quality. This, of course, presents challenges for interpretation. Levac et al. (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010) build on Arksey and O'Malley's work by describing common challenges experienced conducting such reviews. They also recommend a sixth stage involving consultation with stakeholders as a knowledge translation component. Both argue that consultation with policymakers, practitioners and service users can enhance results. Levac et al. suggest that consultations with stakeholders can be conducted when sharing findings to offer a deeper understanding of results and obtain content expertise. They also describe using focus groups, interviews and surveys for feedback on scoping review results for knowledge transfer and exchange to enhance uptake of findings. Our study involved decision-makers at all stages of the review from stage 1 – definition of the research questions to stage 5 – report preparation, thus moving beyond knowledge translation to iterative integrated knowledge translation (CIHR, 2010).

Figure 1 Stages of the scoping literature review methods and results

The research team

The research team involved 14 researchers and 14 decision-makers from three Canadian provinces (Nova Scotia, Ontario and British Columbia), covering five time zones. Researchers were located at five universities and decision-makers included senior policymakers, managers and practitioners in PC and PH working at national, provincial and local levels. They represented federal and provincial governments as well as PH, PC, home health organizations and associations. The team was interprofessional (ie, nurses, physicians, nurse practitioners, an epidemiologist, a medical sociologist, a dietician, and a PH dentist) and had a range of experiences in conducting literature reviews; some had conducted systematic literature reviews while others had no previous experience. Therefore, mentoring and training in conducting a review was required. In Canada and internationally, there are growing expectations to build practitioner decision-maker/scientist partnerships to promote integrated knowledge translation practice (Lapaige, Reference Lapaige2010) with the aim of optimizing evidence-based practice, policy and management. Using this approach, decision-makers on our team were involved in conceptualizing the scope of the review, relevancy assessment, completing extractions, interpreting results and commenting on report drafts. There were varying degrees of involvement by decision-makers and researchers throughout all stages. The team was supported by five research staff, most working part-time, and nine students (undergraduate, Masters and PhD). In total, 42 people were on the team. A central team set out processes, led training and set up technological tools to assist in the review.

Methods and results

In the following section, methods for each of Arksey and O'Malley's five stages of conducting a scoping literature review (Figure 1) are described and integrated with results, along with a discussion of challenges experienced and recommendations to address them. Expanding on Levac et al.'s (Reference Levac, Colquhoun and O'Brien2010) recommendations for conducting scoping reviews, we discuss the strategies and tools, and enabling technologies that we used to work with a large geographically dispersed team involving researchers and decision-makers (summarized in Tables 1–3).

Table 1 Stage 1 – determining the research questions and stage 2 – identifying relevant studies

PC = primary care; PH = primary health.

Table 2 Stage 3 – study selection

PH = primary health.

Table 3 Stage 4 – charting the data and stage 5 – collating, summarizing and report preparation

Stage 1: identifying the research question

Research questions

Researchers and decision-makers attended a face-to-face meeting to launch a four-year program of research to explore PC and PH collaborations. Goals were to get acquainted with each other and begin to focus on the first study – the scoping literature review – and to determine the research questions for the review. Decision-maker input was particularly valuable in determining these questions, because it ensured greater relevance of the study for practice and policy and thus a greater chance of uptake of the results. Following the launch, members met regularly using teleconferencing combined with web conferencing (Elluminate) to refine the scoping review research questions. Using an ‘application sharing’ feature in Elluminate, software applications, such as Microsoft Word, can be opened, shared and manipulated live during web conferences. This feature was useful for document reviews and editing, training and general communication. Although Elluminate Live! web conferencing supports audio transmission, teleconferences tended to be used alone or in addition to web conferences when decision-makers were involved in meetings, as some organizations’ firewalls restricted web conferencing access.

Defining terms

The scope and complexity of the topic of collaboration between PC and PH introduced a number of challenges. The first challenge was the need to clarify definitions; this was necessary to develop a common understanding of the research questions by the team. As others have noted, there have been numerous debates surrounding the terms ‘primary care’ and ‘primary health care’ (Bhatia and Rifkin, Reference Bhatia and Rifkin2010). Rather than to resurrect and solve these debates, it was critical to determine shared definitions that were understood by the team. Debates occurred during the face-to-face launch, and continued during teleconferences and web conferences that followed where definitions were suggested by the overall program of research lead and other members for consideration. The diversity of team members added to the challenge of arriving at agreed upon understanding of terms. With equal representation of researchers and decision-makers from PC and PH sectors, we engaged in lengthy, rich discussions and eventually reached consensus. The team chose terms that were generally accepted by each sector and were felt to be well understood by service providers and policymakers. We also needed to define the term ‘collaboration’, which also has numerous meanings. The final agreed upon definitions are given in Table 4.

Table 4 Definitions

Stage 2: identifying relevant studies

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In stage 2, inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. Papers published between 1988 and 2008 were included. Since the Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care was released 10 years earlier (World Health Organization, 1978), we expected to see changes resulting from it by 1988. We included papers originating from the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand to ensure healthcare system comparability and applicability of research findings to jurisdictions with organizationally similar health systems to Canada. Papers had to address at least one of the following:

-

• Structures to build collaboration between PC and PH (eg, models, settings, roles, policy, legislation, regulation).

-

• Processes to build collaboration between PC and PH (eg, communication, skills, linkages, outreach, facilitators, barriers).

-

• Outcomes of collaboration between PC and PH (eg, accessibility, quality of care, satisfaction, cost).

-

• Markers of successful collaboration between PC and PH (eg, health-related improvements, new and sustained programs, improved access to services).

Published or unpublished primary studies, theses and literature reviews were included as were papers that included descriptive accounts of collaboration with or without an explicit study design in order to comprehensively map the literature. Papers were excluded if they addressed PH or PC alone, were book reviews, commentaries or editorials, or were not published in English.

Search strategy

The search strategy involved five separate activities including: (i) an electronic database search; (ii) a web search; (iii) a hand search of relevant journals; (iv) connecting with key informant contacts; and (v) a search of reference lists of literature reviews on the topic. In the electronic database search, relevant databases were searched as shown in Table 5. MeSH headings were used as free text key words that were applicable to three areas of interest – PC, PH and collaboration – in combinations using the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ (Table 6). Two librarians – a specialist in PH and a health sciences librarian – independently conducted separate searches of electronic databases, compared results and refined their search strategy to obtain the highest and most relevant yield. They used two reviews (Ciliska et al., Reference Ciliska, Ehrlich and DeGuzman2005; Stevenson Rowan et al., Reference Stevenson Rowan, Hogg and Huston2007) to determine key words.

Table 5 Electronic databases searched for scoping literature review

Table 6 Keywords for electronic database search

A web search was conducted including 52 websites from various governments, associations, research networks and repositories known to the team and key informants. For example, the Center for Public Health and Primary Care Research in the UK; the National Primary Care Research and Development Center, Manchester, England; the North American Primary Care Research Group; and the Public Health Agency of Canada. A general internet search using GOOGLE was also conducted.

The hand search involved 18 key journals that were identified by the team (Table 7). Searches were restricted to six months before June 2008 for monthly journals and one year before for quarterly journals. When journals contained relevant papers, hand searches were extended to three years for monthly and five years for quarterly journals. This search was conducted independently by two team members. The first author and two reviewers worked through two journals together discussing how to distinguish collaboration between PC and PH from other related concepts. This training was needed to assist reviewers who initially were not always clear about determining the nature of collaborations. For example, we were not interested in interprofessional collaboration, but specifically in inter- or intraorganizational collaborations between PC and PH and systemic, organizational and interactional influences on them. Clarity was required to distinguish particular collaborations from collaboration as a concept. The yield of relevant papers from hand-searched journals was small but valuable.

Table 7 Hand-searched journals

Key authors in the fields of PC and PH collaboration in Canada and the United States were contacted to suggest key papers. Reference lists were also reviewed from two bibliographies of two review papers (Ciliska et al., Reference Ciliska, Ehrlich and DeGuzman2005).

All retrieved searches were imported into Reference Manager 10, a bibliographic database program; duplicate references were identified and discarded using the ‘check for duplicates’ command. Duplicates were not always recognized using this command, as databases used to download citations and referencing were inconsistent. Therefore, a manual search for duplicates was also needed. A total of 6125 unique papers were identified for relevance assessment.

Stage 3: relevance testing

Level-I review

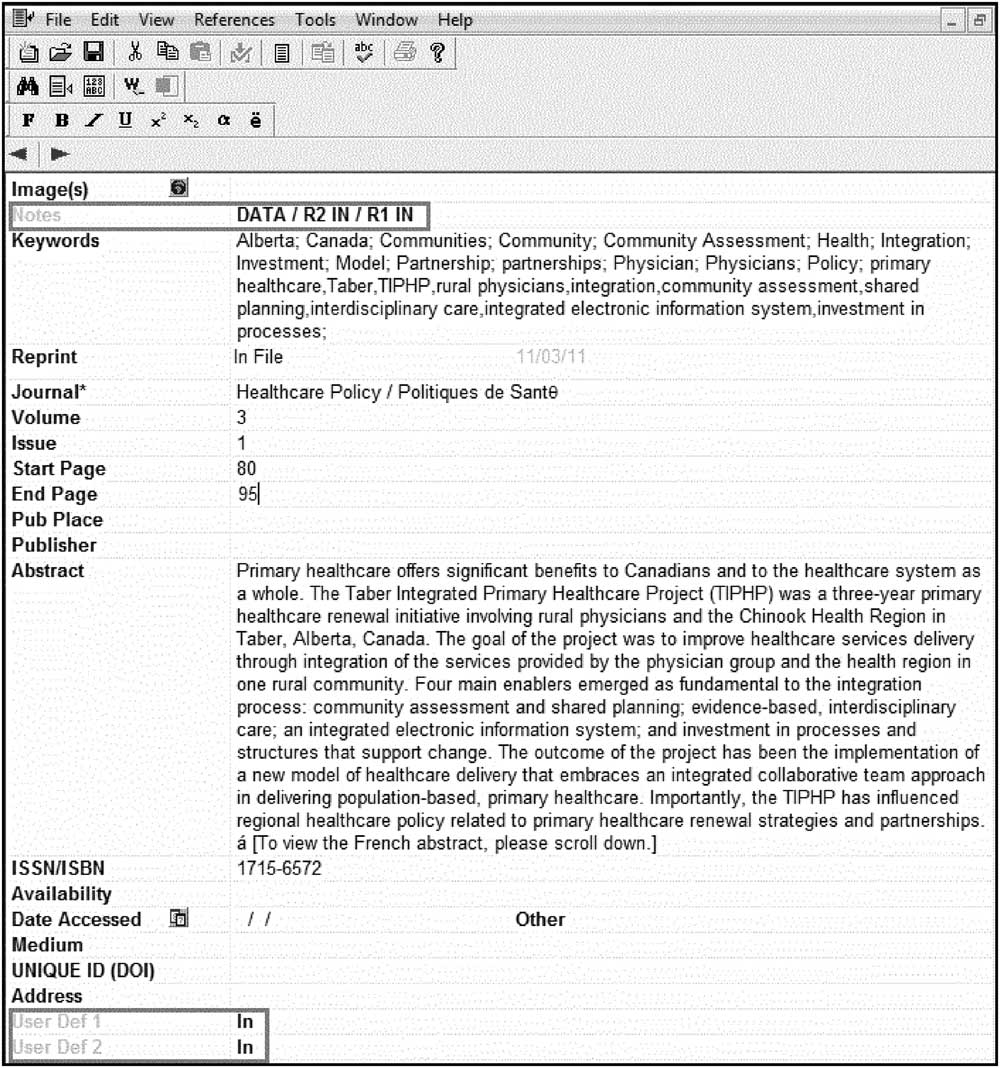

Team members participated in training sessions on two levels of review to assess relevance of papers. Training was conducted using face-to face sessions in each province and Elluminate Live! for the whole team where abstracts were reviewed by a large group. For the level-I review, each title and abstract retrieved from the library database search was independently evaluated by two team members (four teams of two reviewers each). Paired reviewers were assigned to User 1 or User 2 and indicated if the paper was ‘in’ or ‘out’ in Reference Manager's ‘User Defined 1’ field in and ‘User Defined 2’ field for later comparison. To track ratings, independent ratings for each paper were marked by entering ‘R1 In’ (Relevance level I included) or ‘R1 Out’ (Relevance level I excluded) in the master file's ‘notes’ field. The note was edited at various points in the review process, for example, ‘excluded at extraction’ or ‘excluded at analysis’. The use of consistent language in notes fields permitted efficient use of the search function to generate numbers to report the yield.

Other software programs such as DistillerSR (http://systematic-review.net/) can track ratings of reviews and avoid problems with software incompatibility among the team and manual entry of ratings. It also instantly shows areas of disagreement between reviewers. However, costs for such software can be prohibitive and requires training in yet another program. The use of Reference Manager to track relevance ratings significantly reduced our costs; however, coordination of processes was time consuming. Research teams need to take time and cost issues into consideration.

Reviewers were instructed to include papers when there was insufficient information to judge relevance or if they were unsure. Reviewing international literature introduced a challenge because some team members required training in how different healthcare systems are organized. For example, the terms PC and PH did not have the same meaning in all countries. ‘Public health’ was used in the traditional sense as defined by this review in some instances, but referred to a system of publicly funded health care in others, in the United States in particular. Because of the complex nature of these contexts, and inconsistent terminology used to describe healthcare systems and collaborations [ie, Community-oriented Primary Care (United States), Primary Care Trusts (United Kingdom), Community Health Centres (Canada)], it was not surprising that some relevancy rating disagreements occurred.

To assist reviewers, a glossary by Hill et al. (Reference Hill, Griffiths and Gillam2007) was found to be valuable to interpret papers from the United Kingdom, resulting in more accurate ratings and more meaningful extractions in stage 4. Although likely not feasible for many, inclusion of international team members could be helpful. Publications that described healthcare systems for additional background reading were uploaded to a portal (https://ehealthOntario.ca), which among its many functions served as a password-protected secure shared ‘digital filing cabinet’ for the distributed team who were heavily engaged in the review. Review teams can benefit from the provision of key papers describing healthcare systems with which they lack familiarity. Decision-makers were valuable in clarifying healthcare systems within their own provinces as well as other nations. Information technology tools, such as eHealthOntario portal, have been set up to support the government's health strategies. Such portals can be extremely valuable for collaborative research teams to manage data and communicate in a secure fashion. We encourage research teams to approach their governments to inquire about information systems that may be available to them; if not available, researchers are encouraged to request access to such tools especially where research aims align well with government strategic directions.

To further add to challenges in relevance ratings, PC and PH each has their own terminology. Generally, authors tended to assume that readers understand the healthcare sector and thus rarely provided or were brief in descriptions. Therefore, it was essential to have extensive training and opportunities for team members to clarify questions regarding relevancy throughout the review. This and having an interprofessional team increased rigor in selection of papers for inclusion.

As a result of these challenges, all papers required careful review by two team members. It was useful to pair team members from different disciplines or sectors, students with experienced professionals and decision-makers with researchers. When possible, reviewers should be assigned papers that match their area of expertise. To ensure that as many relevant papers as possible proceeded to Level-II review, papers assessed as ‘unsure’ or ‘relevant’ for inclusion by at least one team member progressed to the next level. Using Reference Manager's ‘find’ function, all records containing ‘R1 In’ in the User Defined fields 1 or 2 were identified (Figure 2). As each reviewer entered his/her ratings in separate Reference Manager files, the central team merged them and created a Reference Manager master file. A total of 1089 papers were included at this stage.

Figure 2 Reference manager screen capture of ‘Notes’ field used to mark relevancy ratings for level-I and level-II relevance

It was vital for the central team to provide leadership and support on the use of all technologies early on and throughout the process. Numerous emails, teleconferences and Elluminate Live! web conferences were conducted to orient the team and clarify issues on an ad hoc basis. Web conference recordings of training and review sessions were made available. However, more frequent group meetings aimed at jointly reviewing a larger sample of papers may have helped increase rater congruency and reduced the number of papers moving forward for full-text review.

Level-II review

The next stage of relevance testing consisted of a full-text review of each paper and independent ratings by two members. All required materials were uploaded to folders located on the eHealthOntario portal. A variety of portal features were valuable at this stage, most notably an email notification feature. A notification was sent to reviewers’ emails to provide direct links to specific documents or folders containing required materials for Level-II assessments (eg, forms, instructions and links). This was highly effective for file management, tracking and avoiding personal email overload.

Each review pair was provided with papers included from stage 1, reviewed and marked them as ‘R2 In’ or ‘R2 Out’ for level-II review in Reference Manager. This resulted in 189 papers selected for inclusion. Where there was disagreement between two reviewers, RV and RMM reviewed the papers and made a consensus-based decision. Even with two independent reviewers at each level of relevancy testing, some papers were included that ultimately proved not to meet the inclusion criteria in the final stage. In many cases, this problem was attributable to a lack of clarity in papers and complexities involved in discerning PC and PH collaboration. In a number of instances, relevancy was questioned even in the abstraction stage (stage 4). Therefore, RV and RMM reviewed all included papers and made final decisions about relevance. Despite challenges, we ensured that our process was rigorous by having two levels of review by two independent reviewers, resolution of disagreements by consensus and a final review by RV and RMM. After all review processes were completed, 114 were deemed relevant.

Stage 4: charting the data

In the fourth stage, nine research team members including a number of decision-makers extracted data from relevant papers using a common abstraction form previously piloted with three papers and two authors (RMM and RV; form available on request). We attempted to match papers to extractors’ level of expertise; for example, students were given Canadian papers from their own province where possible. To aid in tracking files, each extraction was assigned a file name corresponding to the bibliographic Reference Manager ID number. A naming convention was developed including the authors’ surname and Reference Manager ID number (eg, Ref ID 0012 Harrison). This was very helpful for report writing (stage 5) to link results to specific document sources for easy referencing.

Using a narrative approach (Arksey and O'Malley, Reference Arksey and O'Malley2005), extractors took a broad view recording details of structures and processes of programs or interventions to contextualize results. The extraction form was derived directly from detailed research questions. These related to the purpose of the collaboration, types of participants in the collaboration, research methods used, the site or context of where the collaboration occurred (eg, urban, rural), theoretical framework applied when related to a collaboration or partnership, the precipitators and or motivators for collaboration, activities of professionals and disciplines, organizations involved, collaboration barriers and facilitators, results/outcomes and indicators of success. Each reviewer had a folder assigned in the portal where extractions were regularly uploaded or downloaded; these were made available to team members to encourage review and feedback. RV and RMM were readily available to team members throughout the extraction phase to clarify questions and consult on process. This enabled the principal investigators to oversee the quality of extractions and monitor daily progress through the portal. When needed, extractions were revised by a second extractor. Although we conducted training sessions on how to complete extractions using Elluminate Live!, it may have been helpful to have given team members a sample of extractions showing the depth and quality expected. A compendium of all extractions is available by contacting the corresponding author.

Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results

Every extraction was imported as a separate document into NVivo 8 (QSR International Pty Ltd., 2008), a qualitative data analysis program maintaining the file names as noted above. Each document (a ‘source’ in NVivo) was imported as an NVivo ‘case’ in read only format: the ‘case’ was assigned ‘attributes’ (eg, year of publication, type of study, country of origin), which was useful for running queries. The coding structure was developed by the first two authors in consultation with the team, guided by the research questions. Content analysis consisted of a two-step process. First-level coding was completed followed by categorizing minor codes into larger themes. A complied list of extractions and the coding structure was shared with team members and reviewed in small groups at four meetings held by audio and web conferences. The main goal was to: obtain team members’ perspectives on emerging themes; determine implications for Canada; and identify future research questions to guide the next phases of the program of research. Each meeting lasted 90 minutes, was audio-taped and subsequently transcribed to assist in analysis and interpretation of results. Web conferencing was extremely helpful to show the coding structure live during meetings where nodes could be expanded and collapsed. However, not all decision-makers could access Elluminate Live! and many found the code book too long and detailed to review. Providing decision-makers with a collapsed coding structure would have been more helpful.

In preparing the final report, RV and RMM used the version control feature in eHealthOntario to ‘check in’ and ‘check out’ draft reports, which provided the option to revert back to or review previous versions of drafts when needed. Although this portal feature was found to be valuable, it was generally only used by the first two authors and project coordinator. The file naming convention described above enabled highly efficient linking of abstracted data from NVivo 8 to Reference Manager 10 citations when writing the report.

Authorship issues were discussed early with regard to a report to funders, but details such as author order proved to be challenging due to: the large team; the decentralized nature of much of the work; and the changing nature of team members’ contributions throughout the process. Typically decision-makers were not as concerned as academics about authorship. Discussions about authorship should begin early in any research process, as others have recommended. In large teams, it may be useful to track participants’ contributions systematically (eg, contributions to development of research questions and tools for the review, number and complexity of reviews and/or extractions completed, number of meetings attended, contributions in report preparation). Although papers related to managing authorship are helpful, (Osbourne and Holland, Reference Osbourne and Holland2009) with the trend to include decision-makers on teams, this task has become more complex, especially when team size is large. The process to conduct the review was also labor and time intensive. It took approximately one and a half years to complete from the program of research launch in early 2007 up to the submission of the first report to funders in September 2008. The time required to complete the review may have been shorter and less complicated to complete if conducted by a smaller local team. Despite these challenges, there was significant value in involving decision-makers on the team. Their assistance in developing meaningful research questions, helping the team to understand complex healthcare systems, interpreting and assisting in the development of implications from results were well worth the effort needed to involve them. Their involvement also supported our aims to increase the relevance of the review for practice and policy, thereby increasing research uptake and the research capacity of all team members. Finally, there is a critical added benefit from having built strong ongoing relationships with decision-makers through the review process; these relationships can be leveraged in future research studies that are grounded in current and relevant practice and policy issues.

The yield

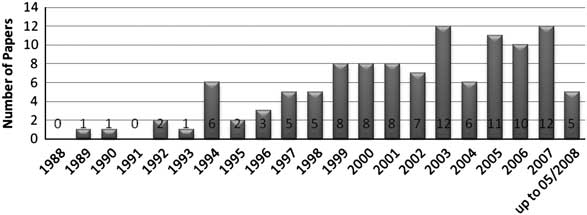

The number of papers (n = 114) related to PC and PH collaboration has grown steadily since the mid-1990s, with the largest growth from 2003 to 2007 (Figure 3). The review included papers up to May 2008 and mapped the origin of the sources of literature on collaboration. The majority of papers originated from the United Kingdom (38%), the United States (34%) and Canada (19%). The remaining papers were from Australia (6%), New Zealand (1%), Finland (1%) and one was an internationally authored review paper (1%). Excluding literature reviews, discussion papers and some research papers, 80 (70%) papers reported on specific collaborations. Settings were identified or surmized in 51 cases. Of these, most reported on collaborations in urban settings (53%) followed by rural (31%), mixed urban and rural (10%) and remote settings (6%). Of 80 papers reporting on collaborations, most were descriptive reports (51%). Research studies accounted for 34 (43%); the remaining publications were program evaluations (31%), literature reviews (9%) or discussion papers (9%). Of 34 papers that reported on research studies, cross-sectional surveys (26%), mixed methods (21%) and qualitative descriptive methods (21%) prevailed. The ‘other’ category included two case reviews, two before and after studies, a case study and a rapid appraisal. In addition, each of the following study approaches was reported: case study, rapid appraisal, grounded theory, action research, historical cohort and randomized controlled trial.

Figure 3 Number of relevant papers published since 1988 (n = 113*). *one report missing date

Conclusions

This scoping review provided a synthesis of literature on PC and PH collaborations as a baseline for a larger program of research aimed to inform health systems on ways to integrate PC and PH perspectives to improve health services and health outcomes. It was not surprising that the frequency of papers published gradually increased 10 years following the Alma Ata Declaration (World Health Organization, 1978) to 2008. With renewed and growing interest in interdisciplinary as well as intersectoral work to improve health (World Health Organization, 2010), it is expected that the knowledge base on collaboration between PC and PH will grow. Although many descriptive papers were included in this scoping review, they were important to include as the topic was relatively uncharted. It is necessary to expand our understanding of what constitutes evidence; it has been argued that colloquial evidence has value (Culyer and Lomas, Reference Culyer and Lomas2006). However, the acceptance of colloquial evidence presents other challenges – what papers should be excluded, how to extract data from them and then analyse the results? These designs do not really allow us to say much about the effectiveness of collaboration on outcomes – yet we can report on a large range of common outcomes.

E-research has been described as the use of advanced information and communication technology (ICT) such as, broadband communication networks, software and infrastructure services that enable secure connections and interoperatability, information data management and collaboration tools to support research activities (Allan, Reference Allan2009). Technology has tremendous potential to assist complex research endeavors especially when research teams are geographically distributed and span many disciplines (Sagotsky et al., Reference Sagotsky, Zhang, Wang, Martin and Deisboeck2008). Virtual Research Environments (VREs) can help researchers conduct and manage the complexity of research activities through the provision of a secure and trustworthy infrastructure to support large- and small-scale teams (Allan, Reference Allan2009). Large research teams supported through VREs can help members manage a multitude of research tasks (Hilyer, Reference Hilyer2010). For example, myExperiment – a VRE-supported collaboration and sharing of experiments, provides a workflow management system (De Roure et al., Reference De Roure, Goble and Stevens2009). Using technology was essential in conducting this scoping literature review to manage the process, especially since the research team was large, distributed geographically and comprised a mixed group of decision-makers, researchers and staff. In our study, the collaborative portal proved to be useful as a confidential shared filing cabinet, although such technologies may be more effective for researchers than for decision-makers who may not be as engaged in the detailed review process. Web conferencing was essential to support ongoing training and communication, although it was important to be cognizant of various comfort levels with technology among team members. Although the use of various synchronous and asynchronous communication tools presented challenges, they facilitated the team to draw on individuals’ strengths, areas of expertise and ways of thinking about issues and the content area. Moffit et al. (Reference Moffit, Mordoch, Wells, Martin-Misener, McDonagh and Edge2009) reported the value in having a project manager on their research team who was responsible to troubleshoot and pilot test technological issues. It is essential to hire staff with strong technology skills and build in extra time for technology training into scoping literature review budgets.

The use of technology was useful, but was it effective? There are a number of lessons that can be learned from our experience. Technologies added benefits by increasing inclusivity of team members and thus gaining interprofessional expertise to inform our ‘yield’ and interpretation of results. Technologies helped engage decision-makers on the team, thereby supporting integrated knowledge translation and capacity building among team members in conducting a scoping literature review – all important secondary goals in our project.

It is not surprising that our team had ICT challenges; the literature supports that there are challenges and generally poor uptake of new technologies by researchers and practitioners. A three-year UK study of Generation Y doctoral students including science, technology and medicine students born between 1982 and 1994 were surveyed around their research and information-seeking behaviors (Exploration for Change, 2009). Few students received training in advanced technology-based tools and resources for seeking literature or conducting research, although their use showed growth over time (Exploration for Change, 2011). The majority did not use emergent technologies such as Web 2.0 tools, VREs or e-portfolios. The authors identified possible reasons for this including inadequate or ineffective use of institution's information technologies to engage students as well as students’ lack of interest in technology training opportunities. Barriers to ICT uptake continue to prevail among practitioners including: work demands, poor computer access, lack of information technology support (Eley et al., Reference Eley, Fallon, Soar, Buikstra and Hegney2008), poor practitioner attitudes to ICT and lack of education and training (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Stevens, Brentnall and Briddon2008; Bhattacherjee and Hikmet, Reference Bhattacherjee and Hikmet2007). Given these barriers, concepts from the Technology Acceptance Model (Holden and Karsh, Reference Holden and Karsh2010) may be helpful to address when incorporating technology to support large research teams. Concepts include perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, social influence/subjective norms and perceived behavioral control/facilitating conditions.

Owing to the size of the team, it was necessary to put measures in place to ensure the quality of the review. The two principal investigators (RV and RMM) and co-investigator provincial site team leads (SW, MM, DMS and LO) had to monitor and review much of the work. The time required for training and consultations was substantial. As conducting a scoping literature review is an iterative process, it is not surprising that the more people involved, the more time it will take. Orientation of research teams is critical with regard to definitions, area of study and context, especially when reviewing international literature.

Given the geographic dispersion of the team, a governance structure that engaged and supported the research team was needed. In this case, RV, who had the most familiarity with all technologies used, had a ‘central’ team that managed the electronic information, such as creating file folders, managing portal access and determining naming protocols for documents. In addition, the ability to successfully use the various technologies was due, in part, to the support of a core group who were available for training, learning and trouble-shooting; these members had sufficient technological skills and were content experts.

Caution needs to be taken not to over burden teams. The learning curve can be significant to get comfortable with several new technologies in a short period of time, the process of conducting a scoping literature review and getting familiar with potentially new content. Involvement of decision-makers in the review process was exceedingly beneficial, because it enabled the scoping review to be more relevant for PC and PH practitioners, managers and policymakers through the knowledge translation process. Although our work did not explore how decision-makers and researchers felt about their engagement on the team, research to explore this question would be beneficial for future large, distributed, interprofessional, research teams with decision-makers and researchers.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the following sponsors for their financial and in-kind support for this program of research: the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; Health Services and Policy Research Support Network (HSPRSN) Partnership Program; the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research; McMaster University, School of Nursing and the Faculty of Health Sciences; the Public Health Agency of Canada; Huron County Health Unit; Victorian Order of Nurses Canada; Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario; Capital District Health Authority, Nova Scotia; Canadian Alliance of Community Health Centres Association; Somerset West Community Health Centre (SWCHC); Canadian Public Health Association; and Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant Local Health Integration Network.