1. Introduction

English Medium Instruction (EMI) has been defined as ‘the use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions where the first language (L1) of the majority of the population is not English’ (Macaro, Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2018, p. 19). This definition has proved to be controversial but has underpinned the work of our research group, from whose collective perspective this article is written. Debates have centred on the role that English language development plays in EMI contexts, and whether this current definitional scope is too narrow in its exclusion of English medium educational practices in Anglophone settings. Pecorari and Malmström (Reference Pecorari and Malmström2018), for example, observe that some members of the EMI research community interpret EMI more broadly to include ‘contexts in which English is a dominant language and in which English language development is supported and actively worked for’ (p. 507). Similarly, Baker and Hüttner (Reference Baker and Hüttner2016, p. 502) state that excluding Anglophone contexts from EMI is ‘unhelpful’ by failing to include the experiences of multilingual students in Anglophone universities who learn through their second language (L2). A focus on multilingualism is also one of the driving forces behind the emergence of new terminology that seeks to shift focus towards the contexts of education, rather than instruction and pedagogy. Dafouz and Smit (Reference Dafouz and Smit2016), for example, prefer the term English-Medium Education in Multilingual University Settings (EMEMUS), because the ‘label is semantically wider, as it does not specify any particular pedagogical approach or research agenda’ (p. 399).

It is undeniable that internationalisation and global student mobility have meant that many Anglophone universities have seen huge increases in student populations who use English as their L2 in a multilingual university setting and where contact with local students is minimal (Humphreys, Reference Humphreys, Fenton-Smith, Humphreys and Walkinshaw2017), but we question whether this characteristic alone make such universities EMI contexts.

While we concur that international Anglophone universities share some of the same issues as international universities globally, we disagree with assertions that they should be unreservedly included in definitions of EMI. To widen the current definition of EMI to include all types of education in English threatens to conflate EMI-issues with wider internationalisation issues and general educational issues. While internationalisation and EMI are clearly connected, many of the issues that form a current research agenda of EMI do not, to date, appear to apply in the same way to universities where teaching through English is not a marked policy decision. If definitional issues are not resolved, the field will encourage poorly defined comparative research, where institutions of vastly different socio-historical, and sociolinguistic contexts are problematically grouped and compared under a pretence that all are English-medium. This may invite misleading conclusions about EMI drawn from data which flouts key tenets of comparative research, such as the principle of equivalence (Jowell, Reference Jowell1998). This principle demands that contexts need be functionally equivalent to be meaningfully compared (Esser & Vliegenthart, Reference Esser and Vliegenthart2017).

In this paper, we provide a research-informed defence for maintaining an explicit definition of EMI that refers to English medium educational practices in predominantly non-Anglophone contexts. Our proposed definition:

1. fortifies links to historical terminology in educational research;

2. acknowledges EMI as a designated policy decision, whether by top-down policy makers or grassroots educational stakeholders;

3. recognises contextual differences in students’ English language proficiency, and guides curriculum developers and practitioners to address language needs;

4. acknowledges differences in L1 use across settings;

5. reflects unique challenges of teacher competence and professional development (PD).

We now present each of these arguments in turn, drawing on EMI research as support for claims made. We also showcase several counterarguments and conclude with a tentative research agenda for comparative research across dimensions of EMI, from which parallels to Anglophone university settings could be drawn.

1.1. Historical terminology in educational research

Some scholars point to the expansion of English as a lingua franca (ELF) in internationalised universities as an argument to include Anglophone universities under the umbrella of EMI. Jenkins and Mauranen (Reference Jenkins and Mauranen2019) preface their edited collection of EMI research – of which two chapters focus on UK and Australian universities – with a contextualisation of how internationalisation brings together multilingual speakers. Similarly, Baker and Hüttner (Reference Baker and Hüttner2016) make assertations that Anglophone universities are of an ‘increasingly multilingual and multicultural nature … in which a significant percentage of students and staff are likely to be using English as a second language (L2)’ (p. 502). While we accept the point that internationalisation and ELF are intertwined, we believe such perspectives of EMI foreground recent developments, especially in Western educational contexts, while pushing historical models of EMI to the background.

One reason we restrict our definition of EMI to jurisdictions where most of the population has an L1 other than English is to reinforce links to historical uses of the term. The term has been traditionally used to problematise the teaching of subject matter in English to student populations in colonial contexts, where other dominant languages are available. As Evans (Reference Evans2017) observes:

The flourishing of scholarly interest in EMI inadvertently conveys the impression that the use of English as a teaching medium in non-Anglophone contexts is a comparatively recent phenomenon and thus tends to overlook, or at least downplay, the long (and admittedly under-researched) history of English-medium teaching in schools and universities in post-colonial Africa and Asia. (p. 68)

Evans goes on to showcase policies in India from 1904 and Hong Kong from 1902 that uses the term English as a ‘medium of instruction’ to highlight language-related educational issues surrounding the teaching of subject matter in an L2, instead of a local language.

These historical policies highlight social and political pressures to teach through English, as well as point to the inherent challenges associated with implementing EMI in contexts where proficiency levels of students and teachers were very low. Many of the historical issues raised in Evans (Reference Evans2017) resonate with issues currently observed in many Expanding Circle contexts today, suggesting that:

… While the nature, origins and trajectory of EMI in Hong Kong and other Outer Circle societies differ markedly from those of its counterpart in Expanding Circle Europe, it is nevertheless possible to draw a number of parallels between developments in Hong Kong and emerging issues in European education, including concerns about the effectiveness of learning and teaching, the marginalisation of indigenous languages and the potentially adverse influence of university-level EMI on MOI [medium of instruction] policy at secondary level. (p. 69)

Li Wei (in Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Hultgren, Li, Tsui and Shaw2018, p. 702) observes that ‘understanding the historical and political dimensions of EMI is crucial to policy and practice, as these dimensions determine the parameters that in turn determine the differences between EMI environments’. We concur with the importance of these historical and political dimensions in guiding research into ‘medium of instruction’ issues in education to ensure EMI environments are comparable in research. This historical perspective on EMI development is much more difficult to use as a lens to explore issues surrounding education in Anglophone countries, where the teaching through English has not emerged in response to colonialism or internationalisation.

1.2. EMI policy decisions

A further distinction between EMI and other forms of English medium education in Anglophone settings relates to policy making. We agree with assertations that internationalisation and EMI in the twenty-first century are inextricably intertwined (Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick2011), as universities turn to English to internationalise (Galloway & Ruegg, Reference Galloway and Ruegg2020). Much research attention has been given to top-down policy making, as universities globally have incentivised the creation of EMI programs in regions such as Japan (Rose & McKinley, Reference Rose and McKinley2018), China (Lei & Hu, Reference Lei and Hu2014), and Taiwan (Lin, Reference Lin2020). These policies seek to create EMI programs to offer domestic students an ‘international’ education ‘at home’, which is seen to facilitate their language development and global competitiveness (Galloway et al., Reference Galloway, Kriukow and Numajiri2017).

These top-down policy trends have also been accompanied by bottom-up strategic decisions, where students and teachers have opted to teach and learn through English, sometimes owing to availability of materials in English (Mazak & Herbas-Donoso, Reference Mazak and Herbas-Donoso2014), or the presence of international students within the classroom for whom English is the preferred academic lingua franca (Lin, Reference Lin2020). In both top-down and bottom-up policy making, the result is a political decision to switch the medium of instruction from the local language into English. As Hultgren (in Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Hultgren, Li, Tsui and Shaw2018) observes, EMI is characterised by ‘the marked policy and practice of adopting English as a medium of instruction where this has not usually been the case’ (p. 703). No such marked shift exists in Anglophone countries, where the use of English as the medium of instruction is the status quo, and not the result of explicit or implicit policy making.

Maintaining a distinction along policy lines is also important to map regional and global growth of EMI programs, as well as to debate critical issues surrounding this global trend. For example, several reports have mapped the exponential growth of EMI in Europe over the past two decades (Brenn-White & Faethe, Reference Brenn-White and Faethe2013; Sandström & Neghina, Reference Sandström and Neghina2017; Wächter & Maiworm, Reference Wächter and Maiworm2008, Reference Wächter and Maiworm2014). One report observes ‘a heated debate’ over the provision of EMI ‘in non-English-speaking European countries’ (Wächter & Maiworm, Reference Wächter and Maiworm2014, p. 15) – a type of debate that is markedly absent in Anglophone contexts. All reports exclude the European nations of Ireland and the United Kingdom from their surveys owing to the impossibilities of attributing growth to EMI policy. In short, in Anglophone nations, there is no marked policy decision to switch the medium of instruction to English, nor is there any substantial controversy surrounding decisions to teach through English. This sets language policies at Anglophone universities apart from EMI policies elsewhere.

This distinction, however, does not negate the importance of research to compare student mobility in English-medium higher education institutions across Anglophone and other EMI universities. In our review of EMI in 52 lower- and middle-income nations, we warned of a Matthew Effect in that if EMI is shown to ‘lead to greater internationalisation of universities, then successful universities [in certain countries] may grow in economic strength at the expense of others – attracting students from the latter.’ (Sahan et al., Reference Sahan, Mikolajewska, Rose, Macaro, Searle, Aizawa, Zhou and Veitch2021, p. 14). We concede that if the purpose of research is to explore phenomena through a lens of internationalisation, then such comparison between Anglophone and non-Anglophone contexts may be warranted, so long as researchers are able to establish that their sample universities are functionally equivalent in their drive for internationalisation, rather than being driven by local or glocal ambitions (such as meeting local demands or producing globally competitive domestic graduates).

1.3. Students’ English proficiency in EMI contexts

We also see stark differences in language proficiency concerns faced by L2 English users in Anglophone universities compared with those observed in EMI contexts. EMI programs may not always explicitly specify English language criteria, in contrast to their Anglophone counterparts, who often require L2 English offer holders to submit English language test results (Lam et al., Reference Lam, Green, Murray and Gayton2021).

The absence of explicit language criteria for universities we characterise as EMI may result in admitting more students with low levels of English language proficiency. For example, Ali (Reference Ali2013) identified vague criteria for students’ English language proficiency in EMI university policy documents in Malaysia, claiming that students must have achieved ‘excellent English proficiency’, and ‘the ability to communicate in English through their academic courses’ (p. 80) to be admitted to EMI programs. Aizawa and Rose (Reference Aizawa and Rose2019) found evidence that policy guidance is ignored in practice, such as a case university in Japan that stated an explicit linguistic threshold (IELTS 6.5) in their university policy guideline, which student and teacher participants largely disregarded. Furthermore, 70% of the EMI students (75 out of 108 participants) who participated in their questionnaire had not achieved the threshold of IELTS 6.5 while still being allowed to attend EMI courses at the university. Owing to heterogeneous levels of student proficiency in EMI, research has reported that many EMI students have not reached the requisite academic English level for adequately comprehending academic content and technical vocabulary (e.g. Cho, Reference Cho2012; Ellili-Cherif & Alkhateeb, Reference Ellili-Cherif and Alkhateeb2015; Evans & Morrison, Reference Evans and Morrison2011; Kırkgöz, Reference Kırkgöz2005, Reference Kırkgöz2014; Sert, Reference Sert2008).

Given that variation is part and parcel of the uniqueness of EMI, we propose (adapting from Macaro, Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2018) four main models of language support in EMI that encapsulate different ways institutions around the world conceive and structure their programmes. In the first of these, the ‘Multilingual Model’, students entering ‘partial EMI institutions’ are offered some access to L1 medium of instruction through a structured system for multilingual practice to occur at the classroom level. Also, in partial EMI institutions, we may find a ‘bilingual model’ of delivery, where EMI courses are offered within bilingual programs alongside other courses in the L1. A second model of EMI embeds language support provision into the programs themselves to combat variability in students’ levels of English proficiency by providing supplementary English courses (of the English for Academic Purposes (EAP) and/or English for Specific Purposes (ESP) type) to aid learning of the chosen academic disciplinary content. We refer this approach to as the ‘Concurrent Support Model’. A third model, the ‘Preparatory Year Model’, is designed to enable students to upgrade their language skills prior to embarking on an EMI program. A fourth model is the ‘Selection Model’, where enrolment on an EMI course is dependent on passing an English language proficiency test with no or little additional required language support. Of these models, Anglophone universities almost universally operate under a ‘Selection Model’, where they offer little English language instruction within the curricula of a university program. Of note, the pre-selection model is widely derided in EMI research as being inadequate for most students’ needs, representing another point of departure between the two contexts.

That educational models of many Anglophone universities differ from other EMI universities does not repudiate the importance to address the language needs of all students learning through their L2. There is clear evidence of a disadvantage for students studying in L2 English even above the required thresholds in Anglophone contexts such as the UK (see, for example, Trenkic & Warmington, Reference Trenkic and Warmington2019). Comparative research of Anglophone and EMI universities such as Baker and Hüttner's (Reference Baker and Hüttner2019) contrast of a UK and Thai university, seek to adopt a critical stance of language support at Anglophone universities, such as their conclusion that:

… in the UK support for English is also needed by students and offered at the university. However, the degree to which this is recognised by lecturers and incorporated into programme aims in the same way as in Thailand is less clear. (p. 91)

While we would accept their critical message that students at Anglophone universities require increased levels of language support, we would urge caution to draw conclusions from comparisons of universities that are not functionally equivalent (by accounts of the researchers themselves) in terms of the language proficiency of students, and the models of language integration they offer because of these differences.

1.4. Use of the L1 in EMI contexts

Many advocates of including Anglophone universities under the umbrella of an EMI context, draw on multilingual practices across contexts as a primary justification (e.g. Baker & Hüttner, Reference Baker and Hüttner2016; Jenkins & Mauranen, Reference Jenkins and Mauranen2019). Most of these researchers are established scholars of ELF – a field that has increasingly foregrounded multilingualism as a central construct (see Cogo, Reference Cogo2017).

While there is no denying the multilingual nature of many EMI classrooms, the presence of an L1 or official language other than English in non-Anglophone countries alters the dynamics of language use in EMI classrooms. In many EMI contexts, most students and their teachers share knowledge of an L1 other than English. In such contexts, research has found that EMI teachers and students generally view the L1 as a facilitative resource for content teaching and learning (e.g. Alkhudair, Reference Alkhudair2019 in Saudi Arabia; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Kweon and Kim2017 in South Korea; Qiu & Fang, Reference Qiu and Fang2019 in China). Research has suggested that teachers and students use the L1 to overcome low levels of English proficiency (e.g. Hahl et al., Reference Hahl, Järvinen and Juuti2016; Hu & Lei, Reference Hu and Lei2014), translate technical terminology (Costa, Reference Costa2012; Wang & Curdt-Christiansen, Reference Wang and Curdt-Christiansen2019), and explain academic concepts (Macaro et al., 2020b; Tarnopolsky & Goodman, Reference Tarnopolsky and Goodman2014). In contrast, a shared language other than English is not a commonly used pedagogical resource in university classes in Anglophone contexts, which largely maintain a ‘monolingual habitus’ (Liddicoat, Reference Liddicoat2016), despite having a multilingual student body. Here, we are not arguing that this practice should go unchallenged in critical research but rather we are pointing to an observed distinction in multilingual pedagogical practices.

L1 use also has implications for social interaction in EMI settings. Kuteeva (Reference Kuteeva2019, p. 296) found that L1 Swedish was commonly used in student discussions, creating an ‘elite’ group of students with proficiency in both English and Swedish. In Taiwan, Lin (Reference Lin2020) found that English was used as a lingua franca when international students were present but that L1 Chinese otherwise served as the primary language of communication among local teachers, students, and administrators. Additionally, research has found that EMI teachers both used (e.g. Costa, Reference Costa2012; Hahl et al., Reference Hahl, Järvinen and Juuti2016) and were reluctant to use (e.g. Roothooft, Reference Roothooft2019) the L1 in lectures when international students were present. These dynamics regarding language choice – for example, to use ELF with international students and the L1 with home students – are different from those found in typical (admittedly, not all) Anglophone universities.

EMI universities must also make decisions concerning the English proficiency of administrative staff and other university employees. International students at an EMI university could face issues communicating with program administrators and support staff who lack English skills, a concern that is unlikely to be considered in Anglophone contexts. Furthermore, as noted earlier under models of EMI, many programs offer bilingual or partial EMI tuition. EMI programs in China are often labelled as Chinese–English bilingual programs (e.g. Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Zhang and May2019; Rose et al., Reference Rose, McKinley, Xu and Zhou2020). Bilingual programs in other contexts have been found to involve the use of English written resources with lectures and discussions conducted in the L1 (e.g. Chou, Reference Chou2018 in Taiwan; Mazak & Herbas-Donoso, Reference Mazak and Herbas-Donoso2014 in Puerto Rico).

Partial EMI programs might include some classes taught in English with the rest offered in the L1 (e.g. Başıbek et al., Reference Başıbek, Dolmacı, Cengiz, Bür, Dilek and Kara2014 in Turkey; Poon, Reference Poon2013 in Hong Kong). As such, the amount of EMI tuition varies across EMI programs, and international students might be expected to possess proficiency in both English and the local language to be able to engage fully in the program. University programs in Anglophone contexts are almost exclusively taught in English, with little expectation that instruction will be bilingual or multilingual. Thus, to label all such contexts ‘EMI’ collapses important categories of multilingual language use at these universities – and may create false platforms for comparative research.

1.5. EMI teachers, pedagogy, and PD

Research shows that many EMI teachers complain they lack linguistic competence to deliver their courses effectively (Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Tian and Chu2020b), particularly to students whose own level of English is often too low (Fortanet-Gómez, Reference Fortanet-Gómez2012). An example of the challenges facing EMI teachers is the range of vocabulary used in content lectures, where no assumptions can be made by the teacher that students will be familiar with ‘everyday language’ and different genres outside of the EMI discipline (Macaro, Reference Macaro2020). Further, teachers’ English proficiency in EMI universities in non-Anglophone contexts may pose challenges to the quality of content teaching (Jensen & Thøgersen, Reference Jensen and Thøgersen2011; Pecorari et al., Reference Pecorari, Shaw, Irvine and Malmstöm2011). Teachers in EMI classrooms have been reported to reduce classroom interaction and elaboration (Sert, Reference Sert2008; Vinke et al., Reference Vinke, Snippe and Jochems1998); ask questions that are both linguistically and cognitively simple (Hu & Duan, Reference Hu and Duan2019); lower the quality of classroom discourse (Pecorari et al., Reference Pecorari, Shaw, Irvine and Malmstöm2011); and water-down content (Hu et al., Reference Hu, Li and Lei2014; Macaro & Akincioglu, Reference Macaro and Akincioglu2018). In other words, it is concerns regarding levels of English of both the teacher and the students in combination that particularly makes teaching EMI the designated pedagogy. Although EMI teaching comes with unique pedagogical concerns, research has shown that PD is rare and pre-service training is even rarer in EMI contexts (Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Akincioglu and Han2020a). There is currently no international certification of EMI teachers, and this is the case also at the national level (see Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Jiménez-Muñoz and Lasagabaster2019 in Spain; Macaro & Han, Reference Macaro and Han2020 in China).

There is growing literature on the approaches and types of PD from which EMI teachers would most benefit. Some of this literature bases its underlying rationale on the need to integrate content and language into teaching (Macaro et al., Reference Macaro, Akincioglu and Dearden2016). It is therefore not surprising Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in the secondary sector should become a reference point for PD courses in higher education (Escobar Urmeneta, Reference Escobar Urmeneta2013; Lo, Reference Lo2020; Park, Reference Park2013), rather than the practices at Anglophone universities. Indeed, there are now regular academic conferences with the title ‘Integrating Content and Language in Higher Education’ (ICLHE) (see Wilkinson & Walsh, Reference Wilkinson and Walsh2015). This drive to foreground the role of language learning through greater interaction in higher education has sprung essentially from the growth in EMI. This focus on comprehension and development of language in relation to content does not feature to anywhere near the same extent in PD programmes in Anglophone countries (Peat, Reference Peat2015). We believe that research revealing good EMI practices in PD could benefit internationally oriented Anglophone universities, so that universities can better support their students. This transfer of knowledge, however, should only be endorsed once the two contexts’ needs are established, via research, as comparable in terms of teachers’ pedagogical needs.

2. Reconciling definitions: Implications and recommendations

In this paper, we have thus far attempted to establish an argument to maintain a clearer definition of EMI based on several key points. While arguing that EMI remains confined to countries or jurisdictions where the L1 of most of the population is not English, we are not stating that EMI provision in such regions is uniform. Nor are we arguing that research that explores English-medium educational challenges in Anglophone contexts is not relevant or needed. Indeed, we would propose that a productive way of providing evidence to the debate underlying the current paper is to carry out preliminary research between Anglophone and non-Anglophone contexts, with the explicit acknowledgement that such research carries with it limitations and caveats. Explorations could, we suggest, be carried out using the following research questions (among others) to establish comparable dimensions:

1. What reasons do students give for embarking on a course taught through their L2?

2. What similarities are there in the interaction patterns found in content classes, including use of the L1, if any?

3. What levels of L2 English competence are required of students?

4. How do students deal with the challenges posed by learning content in L2 English?

5. How much and what type of English language support is offered to students?

6. To what extent are teachers selected to teach content based on their (attested or otherwise) proficiency in English?

7. What amounts, and types, of PD are offered to/required of teachers?

Until research has established equivalency for comparative research, we argue that widening the current definition of EMI might not be the best direction for the field, especially when more appropriate labels exist.

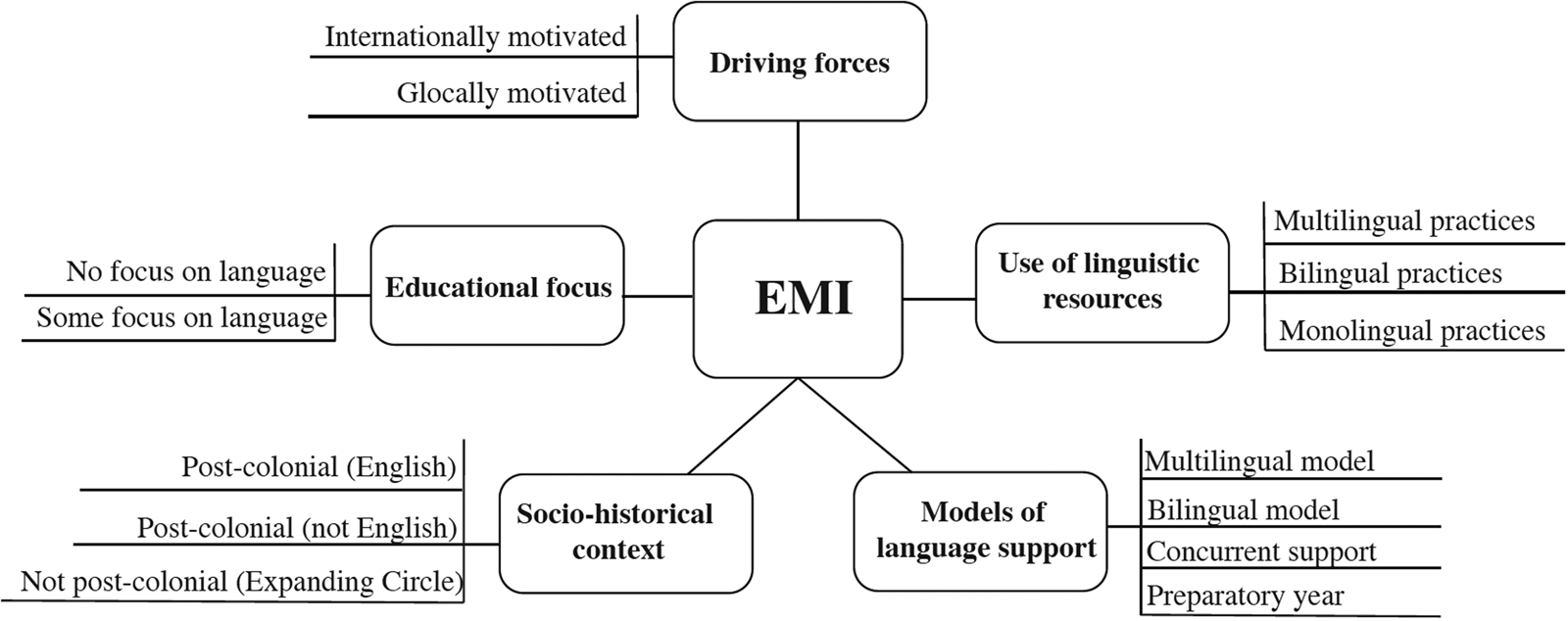

While we agree there is no such thing as a typical EMI setting, we think it is more cautious, for the time being, to demarcate dimensions of EMI to ensure we compare like with like in international comparative studies. Establishing classifications and typologies are cornerstones of comparative research methods, which ‘seek to reduce the complexity of the world by grouping cases into distinct categories with identifiable and shared characteristics … … that allow for a theoretically meaningful differentiation between systems’ (Esser & Vliegenthart, Reference Esser and Vliegenthart2017, p. 4). Several dimensions, as covered in this paper, are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Dimensions of EMI for comparative research

We see the term English medium instruction as the established central term that captures marked educational practices of teaching through English and has historically been applied to describe postcolonial contexts such as Hong Kong (see Evans, Reference Evans2000; Lo & Lo, Reference Lo and Lo2014), and Expanding Circle contexts such as China (Hu, Reference Hu2009). It has also been used as a label to capture a range of educational models, such as bilingual education (Hu, Reference Hu2009). For researchers looking for a central term, English medium instruction offers the most definitional freedom, but comparative research must ensure sociohistorical factors underpinning EMI contexts are considered. It is also important to stress that not all post-colonial contexts are the same: EMI in Hong Kong remains a marked policy decision compared with postcolonial Singapore where English is now a dominant Ll for most Singaporeans. In other contexts such as India, Nepal and Bangladesh, there are huge debates surrounding social inequalities and injustices created by EMI (see, for example, Pramod, Reference Pramod2020). In non-English post-colonial contexts, there are further complications when English is introduced in competition with local languages and former colonial languages such as French and Spanish. While justice and equality issues are intertwined in all educational systems, those present in many postcolonial EMI contexts are manifested differently than in most non-postcolonial EMI contexts.

A further dimension, which may be appropriate to apply to specific university contexts, is the role of multilingualism. EMEMUS (Dafouz & Smit, Reference Dafouz and Smit2016) foregrounds multilingualism in higher education, and thus places focus on the wider linguistic context of the university within which EMI courses are located, and has been used to explore educational practices across international universities that have a large population of international students. However, not all EMI contexts are necessarily multilingual; indeed, many ‘internationalisation at home’ programs specifically cater to a domestic population and are bilingual in presentation. Likewise, many universities that are characterised as EMI may not have a large international student body. As Tsui (in Coleman et al., Reference Coleman, Hultgren, Li, Tsui and Shaw2018) notes:

When learners do not share an L1, EMI becomes a must in an educational setting and English therefore is a lingua franca among speakers of different first languages … When learners do share a common L1 but by choice enrol in an EMI class, the use of English for communication is a conscious, effortful decision, yet easily disturbed by situational factors such as learners’ proficiency levels, content materials, and instructor's adaptability. (p. 715)

Therefore, in largely bilingual EMI contexts, the label of EMEMUS may be misleading, placing as it does greater emphasis on the role of multilingualism and ELF than is actually the case. Thus, this label should be reserved for demonstrable multilingual universities where ELF plays a dominant role in instruction, and in the greater context of the university. For other comparative EMI research, it will be important for researchers to demonstrate comparable linguistic practices, whether multilingual, bilingual, or monolingual in nature.

In this paper, we have emphasised the important role of language support in models of EMI, so it is also worth considering the role of English language development when defining an EMI context. The labels of CLIL and ICLHE have been previously used to describe curriculum models that have a dual focus on language and content development; however, truly integrated language and content curricula are rare in institutes of HE. When language support exists at all in EMI settings, it varies in terms of its integration (Rose et al., Reference Rose, McKinley, Xu and Zhou2020), or serves a preparatory function, rather than holding a dual role (Macaro, Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2018). The labels of CLIL or ICLHE, thus, may be misleading when used to describe EMI models that are not actually dual in focus. Nonetheless, they embody an important dimension of EMI classification—that is whether EMI programs offer an explicit place for a focus on language development in their curriculum structures.

A final issue is how to definitionally separate other forms of EMI that have emerged in response to globalisation. As Pecorari and Malmström (Reference Pecorari and Malmström2018) rightly note, complexities arise in ‘any attempt to present a simple categorisation of the status of English in a particular location’ (p. 502). Nonetheless, in globalised contexts, we see two main types of EMI emerge: internationalised EMI programs, which are driven by neo-liberalist internationalisation forces and are often designed to attract international students; and glocalised EMI programs, which mainly cater to local needs to build-up a domestic student knowledge base and to develop graduates into globally-competitive human resources. Both these contexts are more socio-historically free from colonial ‘baggage’ but nonetheless need to deal with their own discourses concerning a myriad of issues such as domain loss in the national language, anti-globalisation, and, in many contexts, anti-Westernisation.

3. Conclusion

In this paper, we have attempted to untangle some of the contextual complexities surrounding what we see as ballooning definitions of EMI. Baker and Hüttner (Reference Baker and Hüttner2019) have previously argued that ‘separating Anglophone international universities from other international EMI programs, as for example Macaro et al. (Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2018) do, appears unhelpful’ (p. 92). We would counter this observation by arguing that eroding historical definitions of EMI is equally unhelpful, as it muddies the field by creating a catch-all term of educational practices where English is used and invites problematic comparative research where equivalency has not been established. However, there is no denying that models of EMI are diverse (Macaro, Reference Macaro, Curle, Pun, An and Dearden2018), and that there is not a ‘one size fits all’ EMI archetype. This point has been demonstrated not only in this paper, but also in other recent conceptual EMI work that has sought to categorise EMI into typologies (see Richards & Pun, Reference Richards and Pun2021), of which Anglophone contexts are also notably omitted. To place Anglophone contexts within taxonomies of EMI without first establishing equivalency threatens to unravel the connections of an educational phenomenon shared by contexts where English is part of practices emerging from marked policy connected to, but distinct from, globalisation. While we argue that most Anglophone settings are definitionally excluded from what is a global educational trend, this does not devalue research that aims to compare practices across these contexts, especially when efforts are made to match contexts on key dimensions to ensure universities and EMI programs are compared like to like. Unless such concerted efforts are made, research that compares universities and stakeholders’ experiences merely on the basis that teaching and learning is conducted through English creates false associations between research contexts.

Heath Rose is Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics at the University of Oxford and the coordinator of the EMI Oxford Research Group. His research explores the curriculum implications of the globalisation of English. He is author of several books, including Global Englishes for Language Teaching.

Ernesto Macaro is Emeritus Professor of Applied Linguistics at the University of Oxford in the Department of Education. His research focuses on second language learning strategies and on the interaction between teachers and learners in second language classrooms or in classrooms where English is the Medium of Instruction.

Kari Sahan is a Lecturer in Second Language Education at the University of Reading, and an Honorary Fellow of the EMI Oxford Research Group at the University of Oxford. Her research focuses on language policy, teacher–student interaction, and the use of the L1 in EMI classrooms.

Ikuya Aizawa is a researcher in the EMI Oxford research group at the University of Oxford. His EMI-related research focuses on Japan, and has most recently appeared in the journals Higher Education, Studies in Higher Education, and International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism.

Sihan Zhou is a Lecturer in the English Language Teaching Unit at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and, prior to this, a doctoral researcher in the EMI Oxford research group. Her research focuses on EMI and self-regulation in Chinese higher education, appearing in System, ELT Journal, Applied Linguistics Review, and RELC Journal.

Minhui Wei is a researcher in the EMI Oxford research group at the University of Oxford. Her research focuses on second language vocabulary learning, second language learning strategies and language use in classes, especially those using English Medium Instruction in universities in China.