Antipsychotic polypharmacy and the use of higher than the recommended doses of antipsychotics continue to be practised in psychiatry. Reference Tranulis, Skalli, Lalonde, Nicole and Stip1,Reference Clark, Bartels, Mellman and Peacock2 A nationwide audit in the UK involving 32 mental health services revealed that 34-36% of in-patients were prescribed high-dose antipsychotic medications and 39-46% were on antipsychotic polypharmacy 1 year apart. Reference Paton, Barnes, Cavanagh, Taylor and Lelliott3

Polypharmacy and high-dose antipsychotic use has been associated with a number of unfavourable outcomes such as increased side-effects, Reference Carnahan, Lund, Perry and Chrischilles4 increased cost, Reference Zhu, Ascher-Svanum, Faries, Correll and Kane5 and possibly increased mortality; Reference Ray, Chung, Murray, Hall and Stein6 interestingly though, it was noted in a population-based, nested case-control study that combining antipsychotics was not associated with increased mortality. Reference Baandrup, Gasse, Jensen, Glenthoj, Nordentoft and Lublin7 Although there have been a number of studies on this subject, most are based on patients who are acutely ill and who are treated in acute psychiatric wards. Little is known about the extent of this practice among patients who are being discharged from the acute wards. 8 An audit was set out to examine the extent of polypharmacy and high-dose prescribing at the time of discharge from a psychiatric in-patient unit at Penn Hospital, Wolverhampton. We aimed to determine: (1) the prevalence of antipsychotic polypharmacy; (2) the prevalence of high-dose antipsychotics and the associated factors at the time of discharge; and (3) what other medications are commonly given to take home after a period of in-patient stay.

Method

Study design

Discharge summaries are routinely completed for all patients at the time of discharge from in-patient units. This is also true for those who discharge themselves against medical advice. In our trust, one copy of the discharge summary is kept in the patient case note, one goes to the general practitioner, another goes to the hospital pharmacy and one copy is given to the patient. A lot of useful information can be deduced from the discharge summary such as gender, age, diagnosis, a list of medications and their doses, and the duration of admission. This study focused on those discharge summaries available at Penn Hospital pharmacy in which an antipsychotic was given as one of the prescribed medications at the time of discharge. The trust audit committee approved the study.

Inclusion criteria

Discharge summaries of all the patients under the care of the younger adult psychiatric service (18-65 years) who were discharged from the acute psychiatric wards between 2005 and 2008 were examined. Discharge summaries for the over-65-year-olds were only included if the individuals were still being cared for by the younger adult services. The names and doses of antipsychotics prescribed were recorded. Other psychotropics and any medications for physical complaints given were also recorded. Other information such as marital status, history of admission and ethnicity was supplemented from the patients’ case notes.

High-dose antipsychotics

Individuals were considered to be on a high dose of antipsychotic medication if the daily-defined dose of one antipsychotic prescribed was above the maximum British National Formulary (BNF) recommendation (i.e. above 100%) or when the percentage aggregate of two or more antipsychotics prescribed added to more than 100%. The percentage of the maximum BNF recommended dose for antipsychotics highly correlates with other antipsychotic dosage measures such as the World Health Organization daily-defined dose and chlorpromazine equivalent. Reference Nosè, Tansella, Thornicroft, Schene, Becker and Veronese9 It is accepted by the Royal College of Psychiatrists 8 and is widely used in studies. This was the only standard considered in this study.

Data analysis

Analyses were performed using SPSS version 17 on a Mac. Categorical variables were tested by chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test. Binary logistic regression was performed to assess the impact of a number of variables on high-dose antipsychotics. Statistical significance was set at two-tailed P>0.05.

Results

A total of 1001 copies of discharge summaries were available, with 651 individuals (65%) sent home on antipsychotics. The group discharged on antipsychotics formed the basis of this study and comprised 405 males (62.2%) and 246 females (37.8%). The mean age at the time of discharge was 40.2 years (s.d. = 12.1, range 16-69); 75.9% of all patients discharged on antipsychotic medications were between 25 and 54 years of age. Schizophrenia and its related disorders was the most common clinical diagnosis (56.7%), followed by bipolar disorder (26.3%). The majority of patients (67.9%) were single; only 17.1% were either married or cohabiting. For 21.5% of patients, this was their first hospital admission, whereas 78.5% had had a hospital admission in the past. The ethnic constitution of the group was 59.9% White, 18.1% Black, 15.8% Asian and 5.2% mixed.

Antipsychotics given on discharge

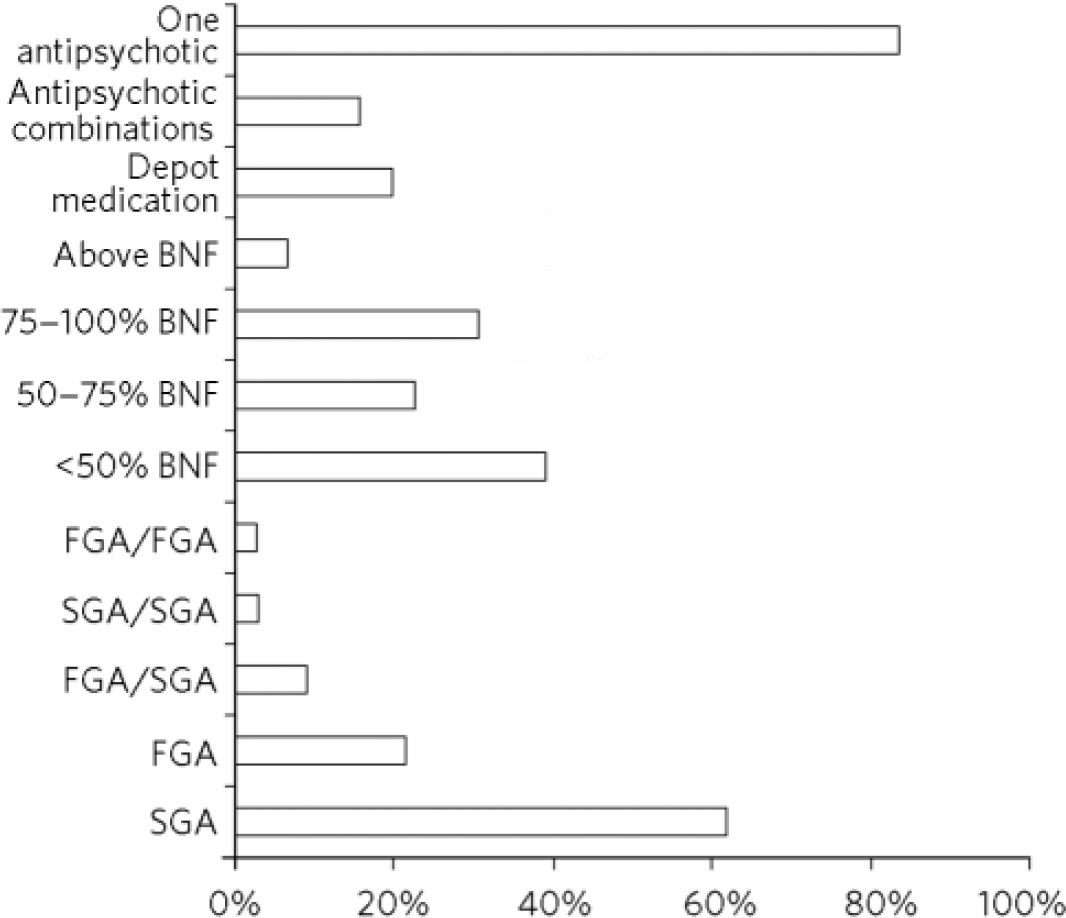

Figure 1 shows the types of antipsychotics and the BNF dose ranges given on discharge. A large proportion of patients (84%, n = 547) were discharged on one antipsychotic, whereas 104 (16%) were sent home on two or more antipsychotics. Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs), either alone or in combination with first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs), were given to 487 patients (74.8%), and FGAs formed part of the discharge antipsychotics to 225 patients (34.6%). A very small proportion (4%, n = 26) was discharged on clozapine. The majority of patients (93.2%, n = 607) were discharged on antipsychotic doses within the BNF limits, with 40% being on antipsychotic doses that were less than 50% of the BNF ranges. Antipsychotics without any other psychotropics were prescribed to 226 patients (34.7%), although only 155 individuals (23.8%) were discharged on one antipsychotic as the sole medication to take home.

Fig 1 Types and dose ranges of antipsychotics given at discharge (n = 651). BNF, British National Formulary; FGA, first-generation antipsychotic; SGA, second-generation antipsychotic.

Doses above the BNF limits

Only a small proportion (6.8%, n = 44) was sent home on antipsychotic doses beyond the maximum BNF limits. High-dose antipsychotic use was associated with male gender, history of admission, use of depot medications, use of any antipsychotic combinations, use of FGA/SGA or SGA/SGA antipsychotic combinations, provision of antimuscarinics, prescription of physical medications, being on any two or more different medications and being admitted over 36 days. No association was observed with other factors such as specific age ranges, diagnoses, and the use of antidepressants, benzodiazepines or mood stabilisers.

Binary logistic regression was performed with nine variables (gender, admission history, depot medications, antimuscarinics, medications for physical illness, admission over 36 days, receiving FGA/SGA or SGA/SGA combinations, being on any combination, receiving a total of any two or more different medications). Only four variables significantly contributed to the model: being on a combination of any antipsychotics (odds ratio (OR) = 24.9, P>0.002, 95% CI 3.22-193.41), being prescribed SGA/SGA or SGA/FGA combinations (OR = 8.6, P>0.004, 95% CI 1.98-37.53), being admitted over 36 days (OR = 4.5, P>0.002, 95% CI 1.76-11.59) and having medications for physical illnesses (OR = 2.9, P>0.046, 95% CI 1.05-8.36).

Antipsychotic combinations

Combinations of antipsychotics were prescribed to 104 patients (16%), with 62 of these (9.5% of total) being discharged on doses within the BNF limits. The remaining 42 patients (6.5%) were sent home with doses beyond the BNF upper limits. The most common combination was FGA/SGA, which was prescribed to 61 patients (9.4%); SGA/SGA and FGA/FGA combinations were given to 22 and 21 patients (3.4% and 3.2%) respectively.

Out of 104 individuals on a combination of antipsychotics, 62 (59.6%) had a depot antipsychotic as one of the medications used in the combination. In 8 patients (7.7%), clozapine was combined with another antipsychotic, and the remaining 34 patients (32.7%) received a combination of other oral antipsychotics.

Other medications

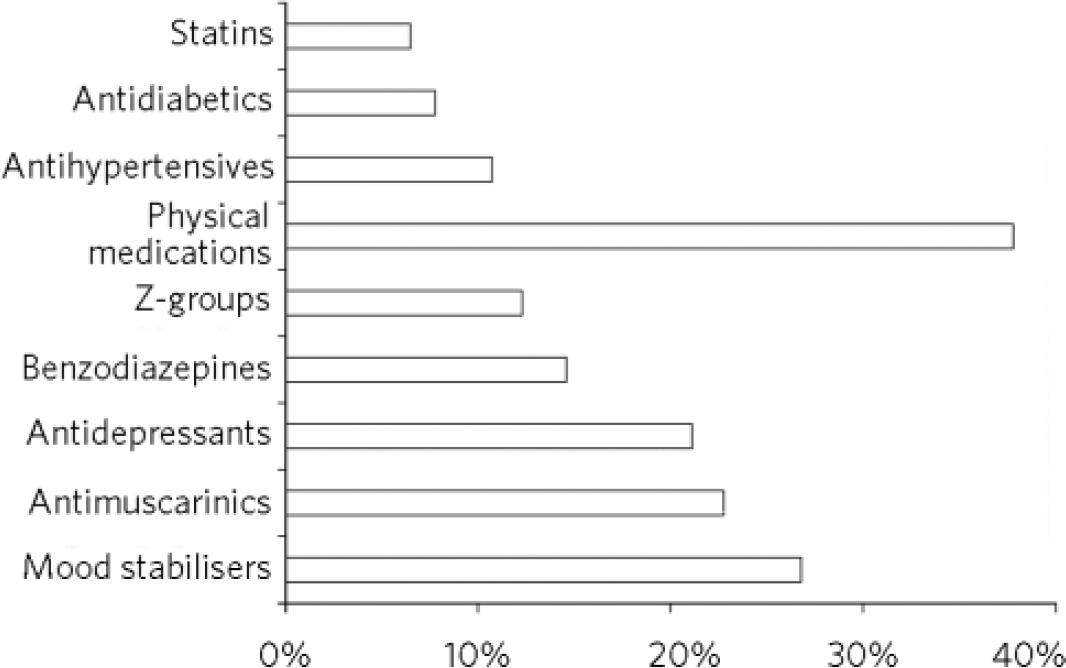

Figure 2 shows what other psychotropics and medications for physical complaints were given on discharge. Medications for physical health problems were prescribed to 247 individuals (37.9%). Antiglycaemics and cholesterol-lowering agents were given to 7.8% and 6.6% of those discharged respectively. Nearly two-thirds (65.3%) had psychotropics other than an antipsychotic. The number of psychotropics given varied from one to five. Just over half (54%) had one or two psychotropics, whereas 11.3% had between three and five. The total number of different medications given to take home (antipsychotics, other psychotropics and medications for physical complaints) varied from 1 to 24 (median 2). There were nine individuals each of whom had ten or more medications. Of these individuals, one had 14 different types of medications, another had 16 and another 24.

Fig 2 Medications for physical illness and other psychotropics given on discharge (n = 651).

Discussion

There is a dearth of information on doses of antipsychotics being prescribed at the time of discharge from acute psychiatric wards. We observed that a small proportion of patients (6.8%) were sent home on high doses of antipsychotics beyond the BNF limits. Our findings are markedly different from an in-patient observation by Paton et al Reference Paton, Barnes, Cavanagh, Taylor and Lelliott3 where up to 36% of patients were prescribed high doses of antipsychotics. Studies from other countries also report higher rates of high-dose antipsychotics given to patients at the time of discharge. About 33% were discharged on high doses in Italy Reference Biancosino, Barbui, Marmai, Dona and Grassi10 and 27% (of patients with schizophrenia) were discharged on high doses in Japan. Reference Ito, Koyama and Higuchi11 Studies based on patients in the community also report higher rates. A study involving four European countries observed that 28% persistently received high-dose antipsychotics, Reference Barbui, Nosé, Mazzi, Thornicroft, Schene and Becker12 whereas Tungaraza et al Reference Tungaraza, Gupta, Jones, Poole and Slegg13 observed that 14% of their UK-based study group were similarly treated.

Why the observed low rate? We can only speculate at this time that a number of factors - most likely operating together - may have accounted for this. First, it is expected that at the time of being discharged, patients are well enough to be managed in the community so much so that medications as needed (p.r.n.) - known to contribute significantly to high doses Reference Paton, Barnes, Cavanagh, Taylor and Lelliott3 - are no longer required. Second, the presence of a number of active teams in the community, for example the crisis and home treatment team, may have helped to maintain in the community individuals with severe illnesses who would otherwise have been admitted to hospital. Finally, high-dose and polypharmacy antipsychotic use varies depending on the population studied, the setting and study design. In our study group, schizophrenia-spectrum disorder was diagnosed in 56.7% and a fifth of the group had never been admitted to hospital before. This mixture may account for the observed low rate.

Factors associated with high-dose antipsychotic use

We observed that the risk of being discharged on high-dose antipsychotics was 5 times higher for patients who spent 36 or more days in hospital compared with those with a shorter duration of hospital stay. A relationship between illness severity, longer in-patient stay and receiving high doses of antipsychotics has been observed in the past. Reference Centorrino, Goren, Hennen, Salvatore, Kelleher and Baldessarini14 This suggests that, all other conditions being equal, patients with severe illness tend to stay in hospital longer and are more likely to require higher doses of antipsychotics. Compared with those who did not receive antipsychotic combinations, the risk of receiving high dosages was 9 times higher if prescribed FGA/SGA or SGA/SGA combinations, increasing to 25 times greater if any combination of antipsychotics were used. This is in agreement with previous observations. Reference Paton, Barnes, Cavanagh, Taylor and Lelliott3,Reference Biancosino, Barbui, Marmai, Dona and Grassi10

Antipsychotic polypharmacy

About 16% of our study group were discharged on antipsychotic polypharmacy. Internationally, the rate of polypharmacy in discharged individuals was 28% in Italy, Reference Biancosino, Barbui, Marmai, Dona and Grassi10 27.5% in Canada, Reference Procyshyn, Kennedy, Tse and Thompson15 35.6% in Norway Reference Kroken, Johnsesn, Ruud, Wentzel-Larsen and J⊘rgensen16 and 40% in the Medicaid group in the USA, Reference Ganguly, Kotzan, Miller, Kennedy and Martin17 all higher than what we observed. However, our finding was similar to that of Centorrino et al Reference Centorrino, Eakin, Bahk, Kelleher, Goren and Salvatore18 in the USA and Barbui et al Reference Barbui, Nosé, Mazzi, Thornicroft, Schene and Becker12 in Italy where 15.8 and 13% respectively were on polypharmacy.

About 60% of those on combination antipsychotics in our study were on combinations involving long-acting depot medication, possibly reflecting a history of poor adherence, a feature that has been repeatedly shown to be associated with patients prescribed injectable antipsychotics. Reference Olfson, Marcus and Ascher-Svanum19,Reference Shi, Ascher-Svanum, Zhu, Faries, Montgomery and Marder20 Interestingly, however, like other forms of antipsychotic polypharmacy, combining depot and oral antipsychotics is widespread among patients with schizophrenia. Around 86% of in-patients who were admitted in the hospitals operated by New York State Office of Mental Health in the USA between 2004 and 2006 were on a combination involving oral and depot antipsychotics. Reference Citrome, Jaffe and Levine21 A study of over 2600 out-patients in California (2001-2004) observed that between 30 and 90% concurrently received oral and injectable antipsychotics. Reference Olfson, Marcus and Ascher-Svanum19 Antipsychotic polypharmacy in whatever form remains a matter of controversy and concern.

A third of individuals on two antipsychotics in our study group were prescribed oral medications. It is possible that some of them could have benefited by switching over to clozapine or clozapine augmentation. Reference Kane, Honigfeld, Singer and Meltzer22,Reference Karunakaran, Tungaraza and Harbone23 However, studies on the use of clozapine augmentation remain inconclusive. Meta-analyses looking at clozapine augmentation with antipsychotics for treatment-resistant schizophrenia have arrived at differing conclusions. One study concluded that the combination ‘is worthy of an individual clinical trial’, Reference Paton, Whittington and Barnes24 another concluded that the augmentation may have a marginal effect, Reference Taylor and Smith25 and yet another indicated that it might have a modest to absent effect. Reference Barbui, Signoretti, Mulè, Boso and Cipriani26 Interestingly, one meta-analysis that looked at combining clozapine and lamotrigine Reference Tiihonen, Wahlbeck and Kiviniemi27 concluded that a ‘substantial proportion… appeared to obtain clinically meaningful benefit from this combination treatment’. Both antipsychotic and non-antipsychotic clozapine augmentation strategies have not shown clear-cut benefits and still warrant further investigation.

Although there are a number of ‘good reasons’ for combining antipsychotics, Reference Langan and Shajahan28,Reference Sernyak and Rosenheck29 the use of antipsychotic combinations is generally discouraged as it is poorly understood and poorly researched. Reference Langan and Shajahan28 A review by Gören et al Reference Gören, Parks, Ghinassi, Milton, Oldham and Hernandez30 observed that ‘limited data’ support the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy for patients with treatment-resistant illness. However, in a double-blind randomised study Reference Lin, Kuo, Chou, Chen, Chen and Huang31 a small group of patients with schizophrenia were randomised to receive either risperidone monotherapy or a combination of low-dose risperidone and low-dose haloperidol. Although no significant difference was observed between the two groups in symptom response, the result favoured the polypharmacy group in terms of the side-effect profile. Those who received risperidone monotherapy had more raised prolactin levels and received more anticholinergic medication than the polypharmacy group. A meta-analysis Reference Correll, Rummel-Kluge, Corves, Kane and Leucht32 of randomised studies involving combination antipsychotics against monotherapy concluded that in a subgroup of patients a combination of antipsychotics was associated with significantly greater efficacy than monotherapy and was also less likely to be discontinued. However, this study heavily relied on Chinese studies, most of which have since been scored as being of low quality. Reference Barbui, Signoretti, Mulè, Boso and Cipriani26 It can be concluded that based on the evidence available, the strategy of combining antipsychotics in its various forms is still in its infancy. It is too early to advocate the use of combinations of antipsychotics routinely; however, lessons can be drawn from other disciplines of medicine where combining medications is a well-known and accepted treatment option. This area needs urgent and serious consideration in psychiatry.

Limitations

The study involved a group of patients from one location and thus may not reflect what takes place in other hospitals. Studies based in several hospitals may be able to provide more generalisable information. Further, our finding applies only to the time of hospital discharge. Longitudinal studies examining the use of antipsychotics from the point of admission to discharge will be able to provide more information on how polypharmacy and high-dose antipsychotic use develops.

The strength of our study is that we had a large sample and our findings are based on real ward activities.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Surendra Singh for his help in statistical analysis, Dr Nilamadhab Kar for helping in the preparation of the initial draft and Hannah Nyakwesi Tungaraza for helping with data input.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.