1 Introduction

1.1 What Is Positive Deviance?

Generally speaking, the term ‘deviance’ can be used to refer to both:

a behaviour or practice that deviates from the norm and may not be socially acceptable

an individual or group that is an outlier in terms of their overall performance.

What we describe in this Element uses the second of these meanings. When we refer to positive deviance, we are describing an approach that involves identifying those who demonstrate exceptionally good performance on particular measures (the ‘positive deviants’) and then trying to understand what allows them to achieve this high level of performance. Their behaviours may differ from the norm, but more importantly they represent behaviours, practices, or systems that facilitate exceptional success.

1.2 The Origins of Positive Deviance and Its Underpinning Assumptions

The term ‘positive deviance’ was first used in the field of international public health in the 1960s. The approach was fuelled by a backlash against a perceived imperialist, professionalised view of public health interventions, and a move to recognise the knowledge and expertise that already exists within communities. For example, Wray, writing in 1972, describing mothers who were able to keep their children fed in the harshest conditions, proposed that:

Such mothers, it would appear, know more than we professionals do. They know how, in that incredible environment, to provide their children with basically adequate diets and to protect them from too frequent infections. Perhaps they can teach us. At the very least, we ought to search out the successful mothers in such circumstances, examine their child care practices, and try to identify what it is they are doing that makes the difference in their children. If we cannot teach these things to other mothers in that environment, perhaps they can.Reference Wray1

The approach is perhaps even more clearly articulated in one of the earliest papers to refer to positive deviance as an alternative approach to studying and improving public health:

[T]o identify those families in which a child between age six months and five years falls in the upper 25 per cent in height and weight measurements. These families are labelled as being ‘Positive Deviants’ from the undernutrition that prevails in the population. They are then studied anthropologically to uncover any practices related to food sources, storage, preparation, consumption, and content. The information would be used in designing food supplementation or other nutritional promotion in the population at large on the assumption that the observed ‘favourable’ practices, although atypical, are feasible and culturally acceptable because they are indigenously rather than extraneously derived.Reference Wishik2

Most famously, positive deviance was used in the 1990s to improve the nutritional status of children in Vietnam.3 In this case, an international charity, Save the Children, identified several positively deviant behaviours, including the unusual practice of feeding shrimps from the paddy fields to small children, and other more accepted behaviours, such as hygienic food preparation.Reference Sternin, Sternin, Marsh, Wollinka, Keeley, Burkhalter and Bashir4,Reference Sternin, Sternin, Marsh and Marchione5 Through an education programme to help others adopt these practices and behaviours, the organisation saw a 74% reduction in severe malnutrition among children under three years of age. This impact was sustained many years after Save the Children left the communities.Reference Mackintosh, Marsh and Schroeder6 Following this, the approach was scaled up to address childhood malnutrition locally and internationally, through a community-based nutrition rehabilitation model combining the positive deviance approach and ‘hearth’ education sessions.3 The hearth approach gathers communities around fireplaces or kitchen hearths for education and rehabilitation and to promote the wider adoption of positively deviant behaviours.Reference Bisits Bullen7,8 Since then, positive deviance has been used to address various public health issues such as pregnancy outcomes,9 the care of newborn children,Reference Marsh, Sternin and Khadduri10 weight control,Reference Stuckey, Boan and Kraschnewski11 and female genital mutilation.Reference Masterson and Swanson12

Although positive deviance can take different forms, its use in international public health is built on some underpinning assumptions:

that positive deviants succeed despite facing similar constraints as others

that solutions to common problems:

◦ already exist within communities (in healthcare, these communities are teams, groups, departments, and organisations)

◦ can be identified or uncovered by anthropological methods

◦ are acceptable, feasible, and sustainable within existing resources because they are already practised by people within the community

that these features increase the likelihood that the solutions are generalisable to, and can be adopted by, other communities.

1.3 Applying Positive Deviance to Healthcare Improvement

Use of the term ‘positive deviance’ has increased substantially in recent years, and many different definitions and applications have now emerged.Reference Herington and van de Fliert13 Since the early 2000s, it has expanded into healthcare and has been implemented in diverse ways. Two key frameworks are often used to help operationalise the positive deviance approach: the 4Ds framework and the Bradley et al. framework. These frameworks are explored in more detail next, although it is important to note that some studies offer only poor descriptions of how positive deviance has been implemented in healthcare.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton14

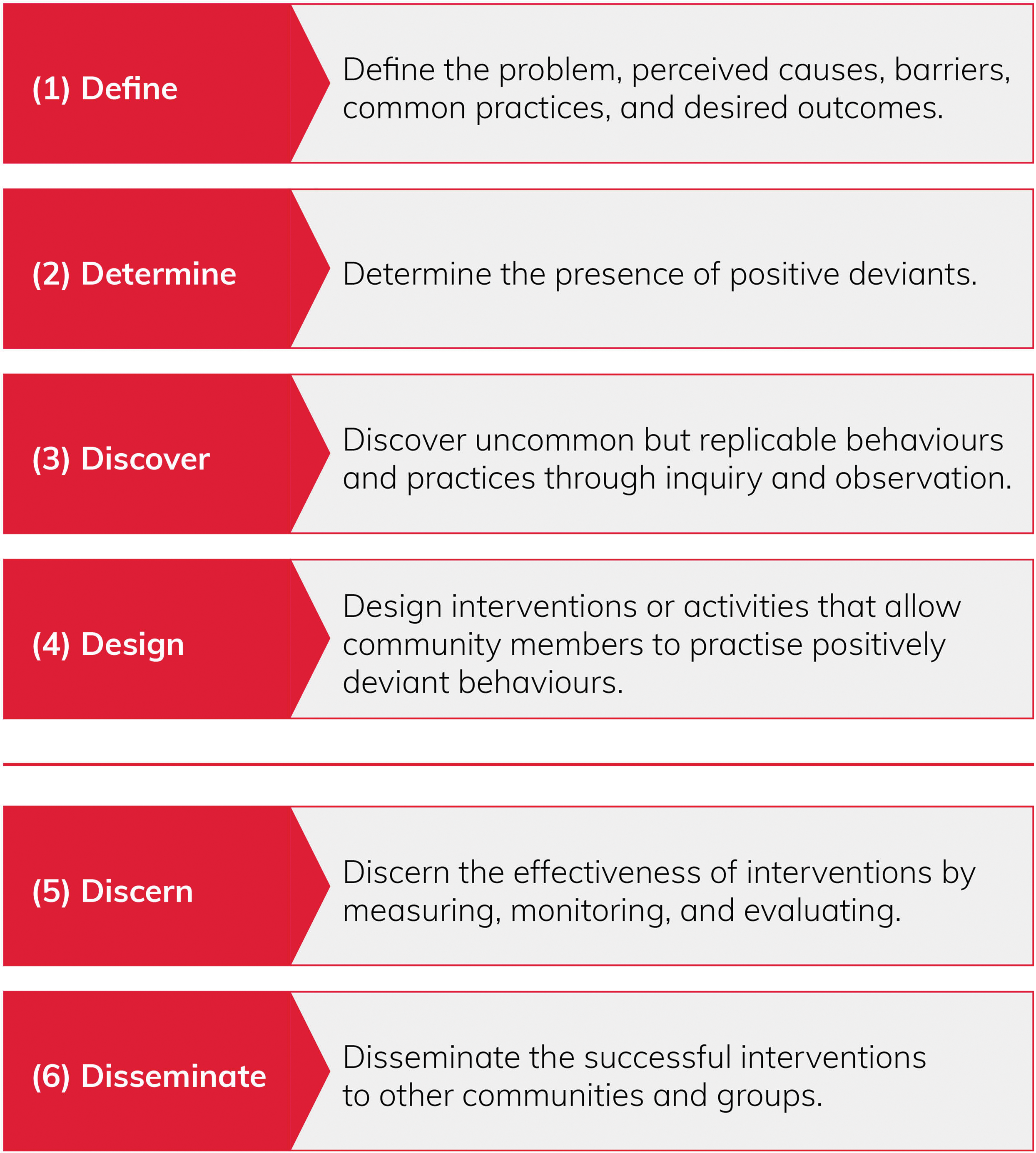

The 4Ds framework (see Figure 1), or variations of it, is most closely aligned to the approach’s origins in international public health. It centres around four steps:

defining the problem

determining the presence of positive deviants

discovering the uncommon but successful strategies

designing interventions to allow others to practise these strategies or behaviours.

Variations of this framework include a fifthReference Initiative15 and sometimes sixth step,Reference Singhal and Dura16 which typically focus on monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of solutions to support wider dissemination (Figure 1). This framework and its variations have been used across a range of studies, for example to reduce MRSA infections,Reference Singhal and Dura16 help smoking cessation among prisoners,Reference Awofeso, Irwin and Forrest17 and to improve how medical students acquire clinical skills.Reference Zaidi, Jaffery and Shahid18

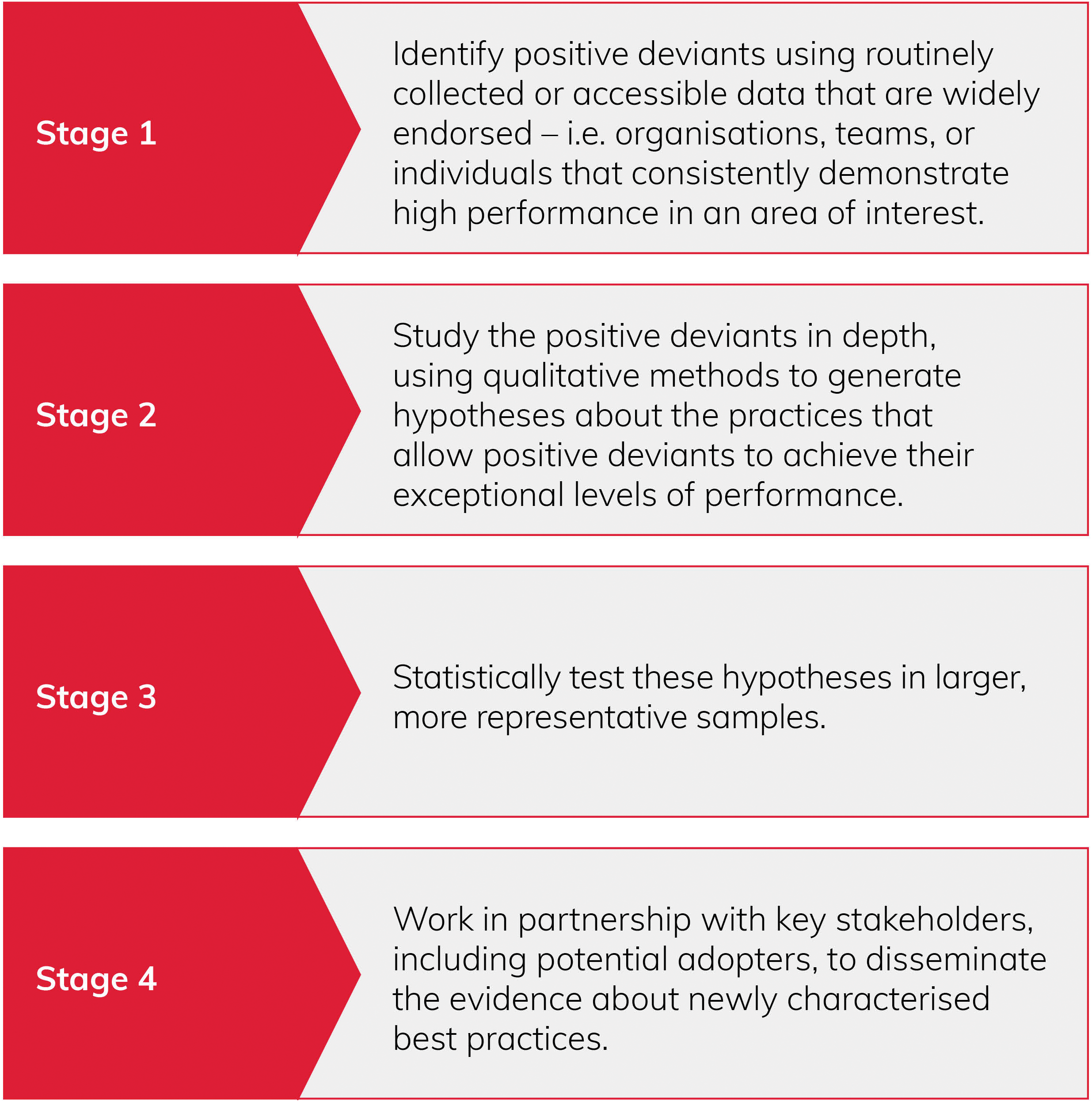

Box 1, highlighting research by Bradley et al.,Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19 describes one of the most well-known examples of a positive deviance study in healthcare. It led to the development of another four-stage framework (Figure 2) designed to support the positive deviance approach in healthcare organisations specifically. Bradley et al. recommend identifying positive deviants using concrete, routinely collected, and widely endorsed data (stage 1). Qualitative methods should then be used to generate hypotheses about the positively deviant strategies used to succeed (stage 2). These hypotheses can be tested in larger, more representative samples (stage 3), and the newly characterised best practice disseminated to others with the help of key stakeholders (stage 4).

Figure 1 The 4Ds/6Ds framework for implementing the positive deviance approach

Box 1 Improving door-to-balloon times for patients with acute myocardial infarction in the USAReference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19–Reference Bradley, Roumanis and Radford21

The Problem

Prompt treatment is critical for the survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction. During 2004–05, a national guideline stated that the door-to-balloon time – the time from the patient arriving in hospital to a stent being inserted to reopen their blocked artery – should be within 90 minutes.Reference Antman, Anbe and Armstrong22,Reference Van de Werf, Ardissino and Betriu23 Yet less than 50% of patients received care that met this target. Door-to-balloon performance had remained static for several years, even though other key cardiac care indicators had improved and some hospitals were managing to meet the target.

How Was Positive Deviance Used?

A team of academics, clinical academics, and clinicians used national registry data to identify 35 US hospitals that achieved median door-to-balloon times of 90 minutes or less for their past 50 cases. These 35 hospitals were ranked according to improvements in this measure over the previous four years, and 11 positively deviant hospitals that demonstrated the greatest improvement were sampled. Researchers used in-depth visits (tours and open-ended interviews) at these 11 sites to explore multidisciplinary staff members’ perspectives and experiences of improving door-to-balloon times. From their qualitative analysis, the team identified contextual factors (e.g. senior management support, shared goals, physician leaders, and interdisciplinary teams) and specific clinical strategies (e.g. activation of the catheterisation laboratory by emergency medicine physicians instead of cardiologists) that they thought were related to top performance in the positively deviant hospitals.Reference Bradley, Roumanis and Radford21

These qualitative findings were then used to develop a web-based survey, which 365 US hospitals completed. For each hospital, survey data were combined with data on door-to-balloon times, and regression modelling was used to identify six specific clinical strategies that predicted lower door-to-balloon times:Reference Bradley, Herrin and Wang20

activation of the catheterisation laboratory by emergency medicine physicians instead of cardiologists

using a single call to activate the catheterisation team

activating the catheterisation team while the patient was still en route to hospital

expecting staff to arrive in the catheterisation laboratory within 20 minutes of being paged

always having an attending cardiologist on site

having real-time feedback for staff on door-to-balloon times.

The American College of Cardiology disseminated these findings to other US hospitals via the Door-to-Balloon Alliance – a public campaign supported by 38 professional associations and agencies. Around 70% of hospitals treating acute myocardial infarction signed up to the alliance and, by 2008, the number of patients receiving treatment within 90 minutes had increased by 25%.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19

Figure 2 Bradley et al.’s four stages to implementing the positive deviance approach in healthcare organisations

The Bradley et al. framework is more data-driven than the 4Ds/6Ds framework, which rarely tests associations between the behaviours and practices identified and the outcomes of interest. It is also more often used at an organisational, regional, or national level (e.g. see studies by Bradley et al., Gabbay et al., and Klaiman et al.Reference Bradley, Byam and Alpern24–Reference Klaiman, O’Connell and Stoto28). Perhaps as a function of this, the framework appears to be predominantly implemented from the top-down, marking a recognisable shift from the original bottom-up applications, where members of the community were integral to all stages of the approach.

Beyond these two frameworks, applications of positive deviance can also broadly be considered to sit on a continuum ranging from those that are ‘community driven’ to those that are ‘externally led’. Positive deviance studies at the community-driven end of the continuum tend to share similarities with those conducted in international public health. Members of the community (i.e. healthcare staff) are typically heavily involved in leading the studies and are central to identifying and creating their own solutions. These studies tend to involve more participatory methods (e.g. discovery and action dialogues or improvisational theatre – see stage 2 of the positive deviance approach in Section 2.2). Though quantitative data can be used, less emphasis is placed on statistically identifying positive deviants and assessing the extent to which their behaviours improve outcomes. Box 2 describes a rigorously conducted community-driven controlled trial in which healthcare staff were integral to identifying positive deviants and how they succeed.Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo31

Box 2 Using the positive deviance approach to address healthcare-associated infections

The Problem

Healthcare-associated infections such as Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are a common cause of ventilator-associated pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and surgical site infections. These infections result in protracted hospital stays and treatment, costing US hospital inpatient services up to $45 billion a year (as estimated in 2007).Reference Buscell, Singhal, Buscell and Lindberg29,Reference Jain, Kralovic and Evans30 Good hand hygiene effectively prevents healthcare-associated infections, yet behavioural interventions are rarely successfulReference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo31 and compliance rates remain relatively low, at around 50%.Reference Buscell, Singhal, Buscell and Lindberg29

How Was Positive Deviance Used?

Marra et al. conducted a controlled trial to improve hand hygiene compliance in two comparable step-down units.Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo31 After a period of baseline data collection, positive deviance was implemented in one unit, while the other acted as a control. In the intervention unit, nurse managers initially identified positively deviant staff who displayed good hand hygiene compliance. Additional positive deviants were then identified over time. The approach was implemented via twice monthly meetings involving staff who worked across a variety of shifts. Meetings provided opportunities to discuss feelings about hand hygiene, what needed to improve, and examples of good practice. Staff created videos, shared healthcare-associated infection rates, and decided to assess individual performances across shifts to create comparison and competition within the team.

After implementing the positive deviance approach, there was a statistically significant, nearly twofold increase in hand hygiene episodes and a significantly lower infection rate between the intervention and control units.Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo31 The success of the interventions led to the extension of positive deviance to the control unit after three months of the trial. Throughout, hand hygiene compliance was evaluated using electronic handwashing counters and the incidence of healthcare-associated infections was monitored.

Following this, an observational study explored the sustainability of the positive deviance intervention.Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo32 For an additional year, staff continued to implement positive deviance on both units and to measure healthcare-associated infections and hand hygiene compliance. Amid concerns that the twice-monthly meetings would become tedious, staff employed motivational techniques (e.g. the parallel thinking process Six Thinking Hats), held interactive sessions to discuss controversial infection control issues, and retained competition among team members. Compared with baseline, each of the two units observed at least a twofold increase in hand hygiene episodes, as well as a significant reduction in the incidence of healthcare-associated infections, suggesting that the improvements gained were sustainable.Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo32

By contrast, at the other end of the continuum, externally led applications tend to be much more concerned with accurately identifying positive deviants using quantitative data. This means that these studies are often conducted by outsider experts (e.g. academics, clinical academics, or clinical/national leads), with perhaps less community or frontline participation. These externally led applications may also use rigorous research methods, such as interviews or observations, to understand what is contributing to positive deviance. Broadly, community-driven applications tend to steer more towards applying the 4Ds framework, while externally led applications favour the Bradley et al. framework. However, it is important to note that this is not a dichotomy. Some externally led applications have extensive clinical stakeholder involvement, while some community-driven applications are conducted rigorously and published in peer-reviewed journals.

1.4 What the Approach Is (and What It Is Not)

Traditionally, healthcare has taken a deficit-based, find-and-fix approach to safety management, using methods such as incident reporting and root cause analysis, and producing guidelines and procedures to eliminate the risks identified.Reference Mannion and Braithwaite33 This approach to managing safety, now commonly referred to as Safety I, seeks to identify the causes of error and harm to eliminate or contain them. The effectiveness of Safety I has been questioned in recent years,Reference Mannion and Braithwaite33,Reference Dixon-Woods and Martin34 resulting in the emergence of the so-called Safety II approach to managing safety.Reference Hollnagel, Wears and Braithwaite35,Reference Hollnagel, Braithwaite and Wears36 Rather than focusing on error and harm, Safety II seeks to understand everyday performance to ensure that as much as possible goes right – that safe care is delivered as frequently as possible under both expected and unexpected conditions.Reference Hollnagel, Wears and Braithwaite35 Furthermore, asset-based approaches, such as Learning from Excellence37 and appreciative inquiry,Reference People38 are increasingly used to improve both the quality and safety of care. Safety II and asset-based approaches share elements in common with positive deviance: they focus on identifying and learning from what goes right rather than being dominated by what has gone wrong and, broadly speaking, they seek to understand ‘work as done’ rather than ‘work as imagined’.

The positive deviance approach is distinctive, however (Table 1). For example, Safety II seeks to generate learning from everyday performance, rather than focusing on extreme performance outliers.Reference Hollnagel, Wears and Braithwaite35,Reference Hollnagel, Braithwaite and Wears36 Acknowledging the complexity of healthcare, Safety II assumes that good and bad outcomes occur in the same way and that safe care is created by people constantly adapting and adjusting to the variable conditions and situations that they face.Reference Hollnagel, Wears and Braithwaite35,Reference Hollnagel, Braithwaite and Wears36 By contrast, positive deviance takes a more linear approach assuming that it is possible to identify and then spread the causes of exceptional performance – the behaviours or processes that reliably lead to exceptional outcomes. Although positive deviance shifts our gaze to the opposite end of the performance spectrum, it could, in essence, be considered akin to a Safety I approach, albeit one that focuses on finding and fixing (i.e. spreading) the causes of sustained positive performances rather than one-off negative incidents or events.

Table 1 Key differences between Safety I, Safety II, and the positive deviance approach

| Safety I | Safety II | Positive deviance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underpinning premise | To ensure that as few things as possible go wrong. Focus on negative outliers. | To ensure that as many things as possible go right. Focus on everyday performance. | To learn from those who demonstrate exceptional performance on outcomes of interest. Focus on positive outliers. |

| Safety management principle | Reactive – respond when something happens or risk is deemed unacceptable. | Proactive – continually try to anticipate developments and events. | Either reactive or proactive – learn from those who overcome specific problems or learn from those who achieve excellence. |

| View of human factors | Humans are predominantly seen as a liability or hazard. They are a problem to be fixed. | Humans are seen as a resource for system flexibility and resilience. They provide flexible solutions to potential problems. | Humans are seen as a source of exceptional performance – they have developed solutions to overcome problems as individuals or within groups. |

| Investigations | Accidents are caused by failures and malfunctions. The purpose of an investigation is to identify the causes. | Things go wrong for the same reasons that they go right. The purpose of an investigation is to understand how care usually goes right, as a basis for explaining how care occasionally goes wrong. | Exceptional performance is caused by positively deviant behaviours. The purpose of an investigation is to identify these behaviours and learn from them. |

Similar distinctions can be drawn between positive deviance and approaches such as Learning from Excellence and appreciative inquiry. Learning from Excellence aims to improve quality of care and staff morale through peer-reported episodes of success, which are shared and, in some instances, discussed or analysed in more depth to generate learning.Reference Kelly, Blake and Plunkett39 Despite its name, Learning from Excellence typically focuses on discrete episodes of everyday success that arise through workarounds, improvisations, and the generosity of staff.40 By contrast, positive deviance focuses on exceptional performance outliers who typically sustain exceptional performance over time.

Appreciative inquiry is a participatory approach that generates organisational change by reframing problems, building on positive ideas, and fostering learning.Reference People38,Reference Richer, Ritchie and Marchionni41 Although appreciative inquiry is used in some applications of positive deviance to uncover success (particularly those that are community-driven or conducted in international public health), it does not specifically seek to learn from those who demonstrate exceptional performance.Reference Trajkovski, Schmied, Vickers and Jackson42

2 The Positive Deviance Approach in Action

Positive deviance has been applied to healthcare improvement at different levels of the system and to address a variety of different problems. This section is structured around Bradley et al.’s framework, as it is thus far the only one that has been designed specifically for healthcare settings.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19 We present cases that exemplify each stage, while also drawing on examples of community-driven applications. Cases are used to highlight some of the challenges and the opportunities of using the positive deviance approach.

2.1 Stage 1: Identifying Positive Deviants

Identifying positive deviants is fundamental to the positive deviance approach, regardless of which framework is followed. Bradley et al. suggest using routinely collected, accessible data to do so.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19 Three major challenges must be overcome at this stage of the approach: measurement, which is notoriously difficult in healthcare; how to analyse the available data to identify exceptional performers; and making like-for-like comparisons to identify true positive deviants.

2.1.1 Measurement in Healthcare Is Notoriously Difficult

The quality and safety of patient care is measured via outcomes and processes. Outcomes relate to observed measures of morbidity and mortality and so are of greatest interest to patients, clinicians, improvers, and policy-makers. However, process measures, which measure performance based on adherence to established clinical standards, are often more sensitive to differences in the quality of care.Reference Lilford, Mohammed, Spiegelhalter and Thomson43 When looking to apply the positive deviance approach to some improvement problems, routinely collected or accessible outcome data simply do not exist.Reference Dixon-Woods, Leslie, Bion and Tarrant44–Reference Woodcock, Liberati and Dixon-Woods46 Where outcome data do exist, they may not be useful. This may be because clinical outcome data represent a measure that is too blunt (e.g. ‘all’ rather than ‘avoidable’ readmissions) or distal (e.g. mortality). In these situations, process measures may provide a more accurate measure.Reference Lilford, Mohammed, Spiegelhalter and Thomson43,Reference Pronovost, Nolan, Zeger, Miller and Rubin47 For example, if assessing the success of a public health campaign, bowel cancer screening rates could be measured rather than bowel cancer cases.

Furthermore, the expression ‘garbage in, garbage out’ is highly relevant to data issues in applications of positive deviance. Through our own workReference O’Hara, Grasic and Gutacker48 – to explore what routinely available data are available to compare the safety performance of wards, units, and services – we identified some of the pitfalls. They include problems with the measures used to collect data, such as a mandatory staff survey question that asks: ‘When errors, near misses or incidents are reported, my organisation takes action to ensure that they do not happen again.’ At first sight, this item seems reasonable. But, if the organisation’s action is to discipline everyone who makes a mistake, a positive value on this item does not necessarily indicate an organisation that demonstrates safety. Likewise, if reported incidents are used to measure safety, the motivations to report are likely to skew the outcome. People may not report incidents because they are fearful, while others might report incidents, including near misses, in an attempt to get something done about a problem they experience regularly (e.g. short-staffing). Self-reported data are subject to many influences that can make them unreliable for comparing organisations.

To be useful, data also need to be accessible. Data are not always publicly available or collected in a standardised way (e.g. clinical coding can vary across organisations), making it difficult to compare performances across organisations. Furthermore, data may not be available at a level that is relevant to the aims of the study. For example, hospital readmission data are published at speciality level, making it difficult to explore how ward teams achieve exceptionally safe hospital discharges. Though some data are available at team or individual level (e.g. for surgical outcomes49 and national clinical audits50), it is often sparse, unavailable, or very difficult or costly to obtain.

2.1.2 How to Analyse the Available Data to Identify Exceptional Performers

Many applications of positive deviance rank performance data and identify positive deviants as those who perform best.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton14 However, rankings (e.g. in league tables) may not actually identify the best and worst performers.Reference Austin, Jha and Romano51–Reference Rothberg, Morsi, Benjamin, Pekow and Lindenauer53 It is also important to consider the time frame over which positive deviants demonstrate exceptional performance. Some studies identify and learn from one-off successes,Reference Zaidi, Jaffery and Shahid18 while in others positive deviants must sustain their performance over a period of time.Reference O’Hara, Grasic and Gutacker48,Reference Baxter, Taylor and Kellar54 Since a one-off outlying status may not be a reliable indicator of success, it may be preferable to learn from those who have demonstrated excellence over a longer period of time.

A variety of sophisticated statistical techniques can be used to identify high performers, but statistical process control methods are increasingly promoted as an accessible way of measuring variation within healthcare.Reference Pronovost, Nolan, Zeger, Miller and Rubin47,Reference Benneyan, Lloyd and Plsek55,Reference Mohammed, Worthington and Woodall56 These methods combine statistical rigour with the ability to sensitively measure performance variation – they distinguish between variation that is to be expected (noise) and variation that may have an assignable cause (e.g. variation that may result from the presence of positive or negative deviants). The methods are sensitive to small sample sizes, can facilitate temporal analysis, and the visual rather than tabular presentation of data makes it easier to identify performance outliers.Reference Marshall, Mohammed and Rouse57 For more information, see the Element on statistical process control.Reference Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic58

2.1.3 Making Like-for-Like Comparisons to Identify True Positive Deviants

The third challenge relates to an underpinning assumption of the approach – that positive deviants succeed despite facing similar constraints as others. This is important, because, for example, some apparent high performers may succeed simply because they care for a less complex or acute patient population, or because the service is better funded. It is important that study samples are carefully selected to account, control for, or minimise confounding variables so that, as far as possible, like-for-like comparisons are made. Nevertheless, accurate case-mix adjustments are often extremely difficult and, depending on how they are made, different high and low performers may be identified. Some confounders will also always remain unmeasured and thus unaccounted for within the adjustments. For a more detailed discussion of this, see Lilford et al.Reference Lilford, Mohammed, Spiegelhalter and Thomson43

2.1.4 Could a Non-Data-Driven Method Be a Solution?

If the positive deviance approach is to be distinguished from other asset-based improvement approaches, based on its premise of learning from exceptional performers, then positive deviants should represent an outlying population. To overcome the challenges above, several studies have identified positive deviants in non-data-driven ways, for example by selecting award nominees.59,Reference Sheard, Jackson and Lawton60 Marra et al.Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo31,3Reference Wishik2,6Reference Wray1 identified positive deviants using tacit knowledge rather than data (see Box 2 for an overview of the study). Initially, nurse managers identified healthcare workers who they considered to be positively deviant and, over time, these individuals identified other positive deviants within their team. Positive deviants displayed good hand hygiene compliance, had a desire to change and develop ideas, and stimulated compliance across the team.3Reference Wray1 Alternatively, some projects, predominantly those that are community-driven, do not identify positively deviant individuals or teams. Instead, discovery and action dialogues (see stage 2 in Section 2.2) are used to define and generate ownership of problems and to identify uncommon behaviours or practices. When positive deviants are identified in non-data-driven ways, it is not known whether they truly display exceptional performance. However, despite this, Marra et al. were able to demonstrate significant improvements in hand hygiene compliance and associated outcomes.Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo31,Reference Marra, Guastelli and de Araujo32,Reference Marra, Noritomi and Westheimer Cavalcante61

2.2 Stage 2: Generating Hypotheses about How Positive Deviants Succeed

In this stage, qualitative methods are used to generate hypotheses about the positively deviant strategies that facilitate exceptional performance.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19 In our own work, we have explored how positively deviant older people’s medical ward teams deliver exceptionally safe patient care, as measured by the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) Safety Thermometer data – a routinely collected measure of four commonly occurring harms.Reference Baxter, Taylor and Kellar54,Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton62,Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton63 We conducted multidisciplinary focus groups and informal observations on four positively deviant and four above-average comparator wards to gather a wide range of perspectives and generate discussion about how teams successfully deliver safe patient care. We also made brief field notes following each focus group to capture factors such as team dynamics. In total, 14 positively deviant characteristics were identified, such as knowing one another well, working together, having integrated allied health professionals, and team stability. These characteristics were either present only on the positively deviant wards or enacted in a substantially different way on the positively deviant wards compared with the comparators.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton63

This study illustrates some important considerations for undertaking stage 2 of the positive deviance approach: what lens should be applied and should a framework be used to guide data collection; do teams have the skills and capacity required; how might sampling and comparators influence the hypotheses generated; and are there other ways to create opportunities for discussion to generate learning?

2.2.1 Consider What Lens to Apply to Qualitative Data Collection

Many studies focus on specific processes and outcomes of care, such as providing weight loss adviceReference Kraschnewski, Sciamanna, Pollak, Stuckey and Sherwood64 or anticoagulation control.Reference Rose, Petrakis and Callahan65 Bounding the scope of studies may make it more feasible to generate an in-depth nuanced understanding of the behaviours or processes that facilitate success, particularly if time and resources are limited. However, in doing so, it is still important to apply a broad lens so as to explicate the wider contextual influences (e.g. policies, leadership, and culture) that facilitate success and to illuminate any unintended consequences (positive or negative) that may arise from the positively deviant strategies. If trying to improve narrow processes or outcomes of care, it is important to think broadly about the factors that may influence exceptional performance and direct the qualitative gaze appropriately.

Alternatively, studies may want to explore how positive deviants succeed on broad outcomes of care to deliver high-quality or safe care in the round. For example, rather than focusing on specific harms (e.g. falls or pressure ulcers), our study on medical wards for older people explored how teams deliver exceptionally safe care across a range of measures.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton63 By looking at those who succeed across a bigger picture, it may be possible to uncover latent factors that facilitate their success – the upstream, system-level factors that are more difficult to observe, such as staffing and skill mix, leadership style, culture, and physical environment. In doing so, it may be possible to target these latent factors to generate improvement across a range of outcomes.

2.2.2 Consider Using a Framework to Guide the Collection of Qualitative Data

Regardless of which lens is taken, qualitative data collection and analysis in positive deviance studies may benefit from using a theoretical framework to help ensure that factors underpinning exceptional performance are comprehensively assessed.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton14,Reference Davidoff, Dixon-Woods, Leviton and Michie66,Reference Rose and McCullough67 For example, Rose et al. structured their qualitative enquiry in anticoagulation clinics around nine key domains that were considered essential to establishing and maintaining a high-quality anticoagulation control.Reference Rose, Petrakis and Callahan65 For patient safety research, the Yorkshire Contributory Factors FrameworkReference Lawton, McEachan and Giles68 or the Manchester Patient Safety Framework69 might be useful.

Beyond safety, researchers or improvers could use frameworks such as the COM-B behaviour change wheelReference Michie, van Stralen and West70 or the PARIHS (Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services) framework.Reference Rycroft-Malone, Harvey and Seers71 Nonetheless, care must also be taken. Positive deviance is inherently an inductive (i.e. emergent) approach.Reference Stuckey, Boan and Kraschnewski11 If applied rigidly, the use of a theory or framework might bias the data generated and blind the observer to those unusual, perhaps deviant practices or factors that might have been identified inductively or that fall outside the scope of the particular theory or framework used.

2.2.3 Tailor the Method to the Skills and Capacity of the Teams Involved

In choosing a method to generate hypotheses about how success is achieved, those conducting a positive deviance study should consider the skills and capacity within their teams. Particularly among externally led applications of positive deviance, a common approach to generate hypotheses about success has been to use ethnographic methods such as extensive observations and formal or informal interviews. These methods facilitate a robust in-depth inquiry and may be well suited to uncovering the beliefs, values, and assumptions that underpin success on broad outcomes of care. For example, Liberati et al.Reference Liberati, Tarrant and Willars72 conducted an ethnography consisting of approximately 143 hours of observation, semi-structured interviews, and focus groups to explore how a maternity unit in England achieved and sustained exceptional safety outcomes.

Yet these methods are rarely accessible to frontline clinicians and improvement organisations (e.g. national audit teams, clinical commissioning groups) that may lack the capability and capacity required to conduct them. If positive deviance is to be used for healthcare improvement, as distinct from research, it may be necessary to challenge one of the underpinning assumptions of positive deviance: that success should be uncovered anthropologically. Our study on older people’s medical wardsReference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton63 tested pragmatic methods that were more (although not completely) accessible to an improvement community. We found that relationships across the multidisciplinary teams enabled people to know one another socially, as well as understand and value each other’s roles. The teams worked to extremely high standards and expectations, and staff could raise safety concerns or ask for emotional and technical help when needed. These findings share similarities with those produced by the more extended investigations undertaken by Liberati et al.Reference Liberati, Tarrant and Willars72 and so, given this, it may be possible to develop a method that is both feasible within an improvement context and sufficient for generating robust hypotheses about how positive deviants succeed. Future research could usefully explore the extent to which different methods can generate robust hypotheses at stage 2, and what the resource implications of these different methods are.

2.2.4 Consider How Sampling and Comparators May Influence the Hypotheses that Are Generated

Having a comparator is a useful addition to a positive deviance study, not least because it is important to understand how positive deviants differ from the rest of a population. Many positive deviance studies do not sample comparators during stage 2 and, where they do, they tend to be negative deviants – the worst performers in a population.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton14 The stark comparison provided by sampling positive and negative deviants may make it easier to identify very obvious differences between the two groups. However, this comparison does not necessarily help identify behaviours and strategies that distinguish positive deviants from those in a population who simply perform well – those with average performances. Sampling comparators that demonstrate good or average performances may help uncover how positive deviants differ from the majority of a population in order to achieve truly exceptional performance.

It is also important to consider how many positive deviants and comparators to sample. Sampling multiple positive deviants and comparators (e.g. Baxter et al.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton63 and Curry et al.Reference Curry, Spatz and Cherlin73) may lead to more generalisable hypotheses, whereas sampling a single positive deviant (e.g. Liberati et al.Reference Liberati, Tarrant and Willars72 and Hughes et al.Reference Hughes, Sheard, Pinkney and Lawton74) may help generate an in-depth picture of exceptional performance within that particular context.

2.2.5 Create Opportunities for Discussion to Generate Learning

Many positive deviance studies do not necessarily use rigorous research methods to uncover positively deviant strategies. Particularly when following the 4Ds framework, some, as we noted above, use discovery and action dialogues. For these dialogues, interested people are brought together for facilitated discussions to uncover positively deviant practices (and positive deviants in some cases), to generate new solutions for improvement, and to identify ways of overcoming existing barriers.75 For example, in trying to reduce bloodstream infections, Lindberg et al.Reference Lindberg, Downham and Buscell76 used discovery and action dialogues to discuss infection causes, strategies and barriers to prevent infection, whether certain people frequently overcame these barriers, other improvement ideas, and how these ideas might be initiated. Other studies use improvisational theatre in which short dramas and scenarios are acted out, providing frontline staff with a social, sensory, and collaborative way to learn and discover together.Reference Hughes, Sheard, Pinkney and Lawton77

2.3 Stage 3: Testing Hypotheses in Larger Samples

In stage 3, the hypotheses generated during stage 2 can be tested in larger, more representative samples to explore their associations with improved outcomes.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19 Few publications explicitly report this stage of the framework; we use Bradley et al.’s original researchReference Bradley, Herrin and Wang20 to exemplify this stage.

2.3.1 Using a Survey to Test the Hypotheses

Box 1 outlines Bradley et al.’s use of national registry data to identify 11 positively deviant US hospitals that had consistently achieved and shown improvements in the 90-minute door-to-balloon time target. After identifying several processes and organisational contextual factors that were thought to facilitate exceptional performance,Reference Bradley, Roumanis and Radford21 the researchers conducted stage 3 by creating a web-based survey to explore the extent to which hospitals within the wider community implemented the processes that had been identified.Reference Bradley, Herrin and Wang20 The survey addressed 28 key hospital strategies that could be objectively and reliably measured using close-ended, multiple choice questions (e.g. the process for activating the catheterisation team). It was piloted for clarity and comprehensiveness, and then distributed to 500 hospitals across the USA.

Hierarchical generalised linear modelling was used to identify six hospital strategies that were associated with significantly faster door-to-balloon times (e.g. the emergency department activating the catheterisation laboratory while the patient is en route to hospital, and always having an attending cardiologist on site). Some of these associations were particularly strong and were estimated to save 10–15 minutes. Hospitals with faster door-to-balloon times had implemented more of the effective strategies.

2.3.2 How Useful Is Stage 3?

Bradley et al.’s studyReference Bradley, Herrin and Wang20 highlights the benefits of conducting stage 3 of the positive deviance approach. By testing hypotheses in larger, more representative samples, they demonstrated which strategies were associated with improved outcomes and dismissed those that were not, allowing them to focus on the most important strategies. Stage 3 complements an evidence-based approach to medicine and enables resources to be directed in ways that are most likely to generate improvement. Quantitative evidence, such as this, can also provide a powerful motivator for change by convincing others that strategies are worth adopting.Reference Michie, Richardson and Johnston78

Nonetheless, there are various challenges to conducting stage 3. First, cross-sectional surveys only demonstrate correlation – not causation – and so implementing strategies may not improve outcomes. Furthermore, the direction of the relationship between strategies and outcomes is not always clear. In some cases, exceptional performance may lead to the positively deviant factors observed, rather than the other way round; for example, exceptional performance may generate high levels of job satisfaction within positively deviant teams.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton63

Second, positively deviant strategies are not always amenable to measurement. Routinely collected data are rarely available to adequately assess the hypotheses that are generated through stage 2. It can be difficult to simplify positively deviant strategies into discrete survey items, and to generate valid and reliable questions that sufficiently measure the hypotheses. Furthermore, asking people to rate themselves, their teams, or their organisations presents its own challenges. Survey questions are open to interpretation, especially if they have not been validated. These problems are most pertinent if the survey is assessing contextual or cultural factors, rather than whether specific processes, policies, or procedures are in place. In this case, the contribution of latent factors (e.g. leadership, psychological safety) in facilitating success may be downplayed.

Some community-driven applications of positive deviance collect data to continually monitor performance throughout the life cycle of improvement. This allows improvers to observe the effects of positive deviance strategies on performance,Reference Singhal, Greiner, Singhal, Buscell and Lindberg79 although it is not always clear from the published research articles which changes in practice actually produced any improvements in performance (e.g. when bundles of interventions are implemented). In addition to measuring processes and outcomes, many community-driven applications use social network analysis to measure the impact of positive deviance. This does not provide a measure of the effectiveness of specific positively deviant practices, but can provide an indicator of culture change, which often accompanies the ability to overcome ‘wicked issues’: challenges that are complex and multifaceted, and are therefore beyond the ability of any one organisation to handle in isolation.Reference Lindberg, Downham and Buscell76,Reference Singhal, Greiner, Singhal, Buscell and Lindberg79,Reference Singhal, McCandless, Buscell and Lindberg80

Given the difficulties of measurement and testing associations between positively deviant strategies and outcomes – particularly when these strategies represent latent or upstream factors (e.g. culture and leadership) rather than more concrete processes or strategies – further critical appraisal of the worth of this stage of the framework is needed. While it is important to develop improvement strategies and processes based on rigorous evidence, qualitative evidence may be sufficient when identifying cultural factors (e.g. trusting relationships, people who know one another) that serve to underpin good outcomes.

2.4 Stage 4: Disseminating Positively Deviant Strategies to Others

In stage 4, positively deviant strategies are disseminated to others in the wider population with the help of key stakeholders.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19 There are very few published examples of this stage. One possible explanation is that articles simply do not refer to a positive deviance framework and so dissemination activities cannot be linked to applications of the approach, or it may represent a time lag between completing and publishing this final stage. Another interpretation is that the positive deviance studies may have failed to produce generalised improvement.

2.4.1 Different Approaches to Dissemination

Due to the dearth of literature on this stage, we refer again to the work of Bradley et al., who disseminated their positively deviant strategies with the support of a group of highly influential organisations.Reference Krumholz, Bradley and Nallamothu81 The American College of Cardiology, in partnership with the American Heart Association and 37 other organisations, implemented a well-coordinated and highly promoted national campaign called the Door-to-Balloon Alliance. When healthcare organisations signed up to the alliance, they committed to treat at least 75% of patients within the 90-minute window, and benefitted from a toolkit and change programme based on the positive deviance evidence, individually tailored actions plans, educational initiatives (e.g. workshops, seminars, and an online community), and regional champions to help motivate and facilitate change. Contextually the alliance was set up at a time when national reporting and financial incentives were also being implemented. Evaluation of the alliance showed significant three-year improvements in door-to-balloon times, whereby 25% more patients received treatment within the 90-minute window than before.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19

By contrast, Sreeramoju et al.Reference Sreeramoju, Dura and Fernandez82 took a different approach to spread practices to reduce healthcare-associated infections. Researchers implemented a positive deviance intervention on three randomly selected wards. They conducted interviews and focus groups, collected data via graffiti boards and drop boxes, and identified 12 positively deviant individuals. To disseminate their findings and generate improvement (equivalent to stage 4), the positive deviants, along with the ward managers, infection preventionists, and a research team member, created an action planning group to help spread and implement some of the ideas. The group used the data that had been gathered to sort, prioritise, implement, and evaluate the improvement ideas that had been generated, often through plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycles. Importantly, it was the healthcare staff, rather than the researchers, who owned these plans. Compared with three randomly selected control wards, the positive deviance intervention significantly impacted a trend in patient safety culture (prevented a decline), although no differences were found in social network maps or healthcare-associated infections.

2.4.2 Top-Down versus Bottom-Up Dissemination

These two examples highlight the different ways in which positively deviant strategies can be disseminated. Bradley et al.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19,Reference Krumholz, Bradley and Nallamothu81 took a top-down approach – national organisations created the alliance. By contrast, Sreeramoju et al.’s approachReference Sreeramoju, Dura and Fernandez82 was more bottom-up – although external researchers supported the earlier qualitative work, findings were acted upon and improvement projects were owned by members of the ward teams. There is limited evidence to say which approach is the most effective, and in what circumstances.

Top-down approaches may be better suited to organisation and system-level applications of positive deviance, where influence is required to instigate change at a regional or national level. A bottom-up approach to dissemination is more aligned with the original international public health and community-driven applications of positive deviance. They may suit individual or team level applications, where it is easier to promote the meaningful community involvement. A bottom-up approach may also be better suited to disseminating positively deviant strategies that are less concrete and tangible (e.g. cultural factors), as bringing communities together may enable them to gather a more nuanced understanding of how success is achieved, making it more likely that they will adopt the strategies and appreciate the relevance to their own context. When planning positive deviance studies, greater attention should be given to the role of communities (e.g. staff and patients) and how they can be effectively involved in the approach without it becoming too burdensome.

2.4.3 How Closely Should Others Replicate the Strategies?

A further unanswered question relating to stage 4 is whether other individuals, teams, organisations, and so on should seek to replicate and mimic positively deviant strategies, or instead adopt only their underlying premise. The importance of context in quality improvement is well recognised.Reference Bate, Robert, Fulop, Øvretveit and Dixon-Woods83 Many successful interventions have failed to scale: they do not achieve the same impacts in wards or organisations that were not involved in the original improvement project (e.g. Bion et al.Reference Bion, Richardson and Hibbert84 and Dixon-Woods et al.Reference Dixon-Woods, Leslie, Tarrant and Bion85). Again, the extent to which positively deviant strategies should be mimicked or adapted (and in what ways) may depend on whether it is a procedural or cultural strategy that is being disseminated. In either situation though, it is important that the qualitative inquiries (stage 2) explore not just what positively deviants do to succeed, but also how they achieve these things, and the contextual factors that support or hinder them.

To summarise the four stages in this section, Table 2 outlines some of the key barriers to implementing the positive deviance approach and offers potential strategies to mitigate them.

Table 2 Barriers to implementing the positive deviance approach (as designed by Bradley et al.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19) and potential strategies for mitigation

| Barrier | Potential mitigation |

|---|---|

| Routinely collected data are not available at the level required (e.g. hospital or individual level) to assess the outcome that I am interested in. |

|

| I don’t have much confidence in the quality of the data. |

|

| I don’t have the specialist skills that are required to analyse the data. | Although skills in statistical process control were rare a few years ago, now many data managers in healthcare and research organisations have these skills. Ask for help. |

| I am concerned that the organisation(s), units, or people identified as positive deviants might not be. | With good data and analyses, and by controlling for factors that are known to lead to greater success (e.g. higher amounts of funding, a younger patient population, fewer comorbidities), you can largely avoid this risk. However, it is important to involve the community you are interested in. For example, you might identify five maternity units as positive deviants, but then the doctors and midwives in your community tell you that site four (of these five) is a specialist centre, with higher levels of funding that attracts all of the best junior doctors. Formally then, this site does not succeed despite facing similar constraints as others. It is useful to know this and to understand what resources impact performance, but it should not be included as a positively deviant site for further investigation. |

| I am worried that excellence might not actually be excellence (related to the barrier above). | This is a trap that everyone working in this field needs to be aware of and is why working with the community is so important. Say, for example, you were conducting a study that focuses on injury during restraint in mental health settings. You identify three sites where injury from restraint is much lower. The problem here is a lack of denominator (i.e. the number of restraints), but more worrying is that without assessing the use of anti-psychotics you do not know whether lack of injury is simply a function of fewer restraints due to over-medication. So, always be aware of these balancing measures in your analysis. |

| I don’t have a theory to frame the qualitative work. |

|

| I don’t know which qualitative method to use. |

|

| I am not sure how to test the hypotheses that I have generated about factors leading to success. | As part of a Safety I approach to safety management, it is rarely possible to test hypotheses about factors leading to failure before implementing interventions based on these ideas, so, at one level, you could argue that stage 3 is not essential. There is also little evidence about the importance of this stage or the rigour with which it can be conducted. In some cases, it is very simple to conduct, for example, if you have routinely collected data (e.g. audits) that assess outcomes relating to the specific hypotheses you have generated. However, this is not always possible. As a minimum, we recommend checking the face validity of the hypotheses with members of the population that you are working with – do clinicians and/or patients think the hypotheses are likely to be associated with improved outcomes? |

| Implementing or spreading the ideas is difficult. |

|

We use ‘community’ to refer to the group of people who deliver (and receive) the care under investigation, and staff who deliver care, have patient contact, or administer the process of patient care.

3 Critiques of the Positive Deviance Approach

The use of positive deviance as an improvement approach in healthcare is relatively new, with much of the research published in the past 10–15 years. It is also fair to say that most positive deviance studies in the field are reported in a largely uncritical way. As we have described elsewhere,Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton14 limitations include limited detail on how positively deviant individuals or teams were identified, under-use of comparisons and controls, and absent or poorly reported involvement of staff and patients. Despite the lack of critical reflection in the studies themselves, some opinion and thought pieces that espouse the value of positive deviance do acknowledge its limitations and the difficulties of applying it at scale.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19,Reference Rose and McCullough67,Reference Lawton, Taylor, Clay-Williams and Braithwaite90 Here we describe the key issues to consider before choosing to adopt a positive deviance approach.

3.1 Robust Discoveries Require Robust Data

When embarking on a positive deviance project, it is vital that someone in the team understands data, and that all involved are encouraged to adopt a critical stance on the data, identifying only those measures that are reliable, valid, and meet a set of previously agreed criteria. These problems with poor quality data are not unique to positive deviance.Reference Woodcock, Liberati and Dixon-Woods46 Many improvement approaches (e.g. see the Element on audit, feedback, and behaviour changeReference Ivers, Audit, Dixon-Woods, Brown and Marjanovic91) rely on data either to drive the improvement or to evaluate its impact. Indeed, these same data are used to identify, and take action against, negative deviants.

Given the challenges of identifying positive deviants accurately, it is important to consider the extent to which we should prevent the perfect from being the enemy of the good. If we can improve by learning from those who perform well, rather than from those who perform exceptionally well, perhaps a more pragmatic approach should be embraced. It could be argued that the risk of promoting a practice that is not definitively associated with the highest performing teams or services may be lower than reconfiguring or closing down a service that has been identified to be a negative deviant. Nonetheless, caution should be applied: focusing on the wrong positive deviants may lead to learning that is actually counterproductive for improvement.

3.2 Using Positive Deviance in Healthcare Is Unlikely to Uncover Surprises

Using positive deviance in healthcare organisations in high-income countries is very different from its origins in international public health. The solutions identified in studies of healthcare are rarely exceptionally deviant. They are not, typically, like shrimps in the paddy fields, the unusual practices so often associated with early positive deviance work in Vietnam.Reference Sternin, Sternin, Marsh, Wollinka, Keeley, Burkhalter and Bashir4,Reference Sternin, Sternin, Marsh and Marchione5 Solutions identified in positively deviant healthcare teams and organisations are often things that are acceptable to others; they may be commonly known or evidence based, but perhaps just not uniformly adopted. For example, using alcohol gel in addition to soap and water rather than relying on just one or the other when ensuring hand hygiene prior to central line insertion.Reference Cohen, Gesser-Edelsburg, Singhal, Benenson and Moses92 Alternatively, the hypotheses generated by qualitatively studying positive deviants in depth (stage 2 of the Bradley et al. framework) may be structural or cultural. They might be about psychological safety and trust in multidisciplinary teams, common goals, and transformational leadership. In fact, what these findings might suggest, and it is difficult with the current evidence to deny, is that positive deviance in healthcare may be synonymous with the ability to identify good practice and the contexts that facilitate their achievement.

3.3 The Positive Deviance Approach Must Account for the Complexity of the Healthcare System

Healthcare organisations are complexReference Plsek and Greenhalgh93 and, as such, systems often act in unpredictable ways to produce emergent outcomes. International public health and some of the more community-driven positive deviance studies have been cognisant of this complexity. They have, for example, used participatory methods that engage frontline staff, foster relationships/networks, encourage diverse participation and perspectives, and empower staff to make decisions (see Lindberg and SchneiderReference Lindberg and Schneider94 for further discussion). Through this, the positive deviance approach is able to influence the parameters that shape self-organisation in complex adaptive systems – the natural and local emergence of order, innovation, and progress. Namely, it improves information flow, enhances the number and quality of connections, includes diverse perspectives, and shifts power differentials.Reference Lindberg and Schneider94 However, it might be argued that positive deviance, particularly as conceptualised in Bradley et al.’s framework or by externally led applications, fails to recognise this complexity.

Limited community involvement risks a loss of engagement, connections, diversity, and empowerment, instead reducing the approach to simply finding specific solutions and spreading these to others to fix problems – a somewhat reductionist and linear approach to generating improvement. For positive deviance, key qualities are its asset-based character and its commitment to learning from the bottom up. It is important, then, that the underpinning principle that communities themselves hold the expertise and skill is not lost in a hierarchical healthcare system where policies, targets, and regulation are externally driven.

3.4 Applications Need to Explore the Mechanisms of Change

At the beginning of this Element, we outlined a set of underlying assumptions of positive deviance: solutions exist within communities; positive deviants succeed despite facing similar constraints; and this tacit knowledge can be generalised to others. In addition, Marsh et al. have proposed that the approach facilitates three important mechanisms of change:Reference Marsh, Schroeder, Dearden, Sternin and Sternin95 social mobilisation, whereby communities are motivated to engage with the approach; information gathering, to identify behaviours that facilitate good outcomes; and behaviour change, whereby the wider community adopts these new behaviours. The way that positive deviance has been operationalised in healthcare, a sector where quantitative evidence is central to decision-making, may mean that the mechanisms of social mobilisation and behaviour change have been lost in translation. For example, social mobilisation (bottom-up community involvement) has a central role in many of the typically community-driven studies, but, in the externally led studies, particularly at organisational level, this aspect is typically missing almost completely. If improvers are to stay true to the origins of positive deviance, then it is important that studies clearly align with the underlying assumption of actively involving positive deviants in identifying solutions and spreading them to others. Without social mobilisation, behaviour change becomes something that has to be done at the end of the project to ensure the spread of practices, rather than being an integral part of the process of conducting positive deviance. As such, applications of positive deviance that lack community involvement may face the same implementation challenges, including behaviour change, of any other quality improvement approach.

3.5 There Is a Lot We Do Not Yet Know about Positive Deviance

The use of positive deviance in healthcare is very much in its infancy, meaning there are many questions about its use and effectiveness still to be answered. Much more needs to be understood about how positive deviance works and what the mechanisms of action are. For example, given our aforementioned comments, how critical are social mobilisation, information gathering, and behaviour change? In what ways is positive deviance distinctive or advantageous compared with other improvement approaches? For example, a comparative study that explores the processes and outcomes of audit and feedback versus, or perhaps combined with, positive deviance is one possible avenue for further research.

Future research also needs to test different ways of conducting the qualitative stage of positive deviance. It is important to identify what level of effort is sufficient for generating reliable hypotheses about the factors underpinning excellence. This is even more critical if these hypotheses will not be tested in larger samples before implementation. To what extent should we learn from those who truly outperform? What is the most appropriate comparator group? How important is the wider testing of hypotheses? What do we spread – specific practices, or contextual and relational factors, or both?

One other important but unanswered question is the extent to which the learning from one context can be applied to another. This applies both to specific practices and processes as well as to the structural and cultural features of organisations. In our work in two very different settings (elective hip and knee surgeryReference Hughes, Sheard, Pinkney and Lawton74 and older people’s careReference Baxter, Taylor and Kellar54,Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton62,Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton63) we have found that while some of our findings were similar in both settings (strong multidisciplinary teams and psychological safety), other factors were entirely different, reflecting the nature of these two services. In the more predictable elective service, reliability and standardisation of process were key, whereas in the more unpredictable older people’s service, personalisation and adaptability were critical. Based on these and other findings, we would hypothesise that there will be some fundamental and transferable learning about cultural and structural factors that facilitate excellence across settings and that the growing evidence base will allow, through systematic review, identification of these. But, in addition, there will be other factors (practices, processes, and ways of working) that are not generalisable beyond the service, specialty, or client group.

4 Conclusions

Positive deviance offers a set of core ideas: expertise being held within communities, the importance of learning from communities that succeed, and mobilising communities to spread the learning. Positive deviance resonates with the changing landscape of quality and safety research and improvement, particularly in its growing attempt to understand ‘work as done’ rather than ‘work as imagined’ – a distinction that is at the fore of Safety II thinking. Adopting positive deviance enables learning from the experts doing the work rather than those who commission or regulate the work. This is attractive in conditions where the strain on healthcare resources is high and approaches to improvement based on what is imagined are likely to be increasingly removed from the reality of what is achievable.

Despite its challenges, positive deviance remains promising, particularly as the availability of good quality and cross-sector data grow. As with any relatively new approach, however, many questions remain to be answered about its optimal use and the extent to which findings in one domain are generalisable to another. We must also be prepared to be more critical in applying and evaluating this approach than we have been to date. Finally, it will be important to reflect on the way that positive deviance is being applied in healthcare, with its strong focus on rigorous research methods and data. This may mean losing some of the espoused benefits of community involvement and mobilisation. This tension between rigour and community engagement is likely to be enduring.

5 Further Reading

Several applications of the positive deviance approach have been presented as cases and/or referenced throughout this Element. The following further reading is for those who want to find out more about the approach.

Positive Deviance Collaborative3 – a website containing tools, manuals, case studies, and publications, and that helps to connect people who are implementing the approach. It predominantly aligns with an international public health approach of positive deviance and covers applications from a variety of counties and settings, including nutrition, education, business, and healthcare.

Bradley et al.Reference Bradley, Curry and Ramanadhan19 – a summary of the four-stage framework for applying the positive deviance approach in healthcare organisations, and work to improve door-to-balloon times for patients with acute myocardial infarction.

Lawton et al.Reference Lawton, Taylor, Clay-Williams and Braithwaite90 – a critique of positive deviance as a new approach to improving patient safety within healthcare organisations.

Marsh et al.Reference Marsh, Schroeder, Dearden, Sternin and Sternin95 – a commentary introducing the positive deviance approach and describing evidence for its effectiveness.

Rose and McCulloughReference Rose and McCullough67 – a narrative review of the authors’ experiences of applying the positive deviance approach in healthcare organisations, including potential applications in healthcare and methodological guidance.

Baxter et al.Reference Baxter, Taylor, Kellar and Lawton14 – a systematic review of healthcare applications of positive deviance, exploring how positive deviance is defined, the quality of existing applications, and the methods used within them.

Hibbert and TrubacikReference Hibbert and Trubacik96 – a report detailing how the National Audit for Intermediate Care has used positive deviance to identify and learn from home-based and bed-based intermediate care services in the UK.

Rebecca Lawton and Ruth Baxter conceptualised the outline for this Element together. Both authors contributed to the drafting and reviewing of the Element and have approved the final version.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank the peer reviewers for their insightful comments and recommendations to improve the Element. A list of peer reviewers is published at www.cambridge.org/IQ-peer-reviewers. We also thank all the staff and patients who have participated in our positive deviance studies.

Funding

This Element was funded by THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute, www.thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk). THIS Institute is strengthening the evidence base for improving the quality and safety of healthcare. THIS Institute is supported by a grant to the University of Cambridge from the Health Foundation – an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and healthcare for people in the UK. Our positive deviance studies were funded by the Health Foundation (via a PhD for Improvement Science) and by the NIHR Yorkshire and Humber Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC – under the Evidence-Based Transformation Theme).

About the Authors

Ruth Baxter is a THIS Institute post-doctoral fellow in the Yorkshire Quality and Safety Research Group. Her research interests include the positive deviance approach, adopting a resilient healthcare and Safety II approach to improving healthcare, and involving patients to improve the quality and safety of healthcare services.

Rebecca Lawton is a health psychologist with two main research interests: patient safety and behaviour change. She is Professor, Psychology of Healthcare, at the University of Leeds, founder member of the Yorkshire Quality and Safety Research Group, and Director of NIHR Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translational Research Centre, with a focus on delivering research that makes healthcare safer.

The online version of this work is published under a Creative Commons licence called CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0). It means that you’re free to reuse this work. In fact, we encourage it. We just ask that you acknowledge THIS Institute as the creator, you don’t distribute a modified version without our permission, and you don’t sell it or use it for any activity that generates revenue without our permission. Ultimately, we want our work to have impact. So if you’ve got a use in mind but you’re not sure it’s allowed, just ask us at enquiries@thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk.

The printed version is subject to statutory exceptions and to the provisions of relevant licensing agreements, so you will need written permission from Cambridge University Press to reproduce any part of it.

All versions of this work may contain content reproduced under licence from third parties. You must obtain permission to reproduce this content from these third parties directly.

Editors-in-Chief

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Mary is Director of THIS Institute and is the Health Foundation Professor of Healthcare Improvement Studies in the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the University of Cambridge. Mary leads a programme of research focused on healthcare improvement, healthcare ethics, and methodological innovation in studying healthcare.

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Graham is Director of Research at THIS Institute, leading applied research programmes and contributing to the institute’s strategy and development. His research interests are in the organisation and delivery of healthcare, and particularly the role of professionals, managers, and patients and the public in efforts at organisational change.

Executive Editor

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Katrina is Communications Manager at THIS Institute, providing editorial expertise to maximise the impact of THIS Institute’s research findings. She managed the project to produce the series.

Editorial Team

RAND Europe

Sonja is Director of RAND Europe’s healthcare innovation, industry, and policy research. Her work provides decision-makers with evidence and insights to support innovation and improvement in healthcare systems, and to support the translation of innovation into societal benefits for healthcare services and population health.

RAND Europe

Tom is Head of Evaluation at RAND Europe and President of the European Evaluation Society, leading evaluations and applied research focused on the key challenges facing health services. His current health portfolio includes evaluations of the innovation landscape, quality improvement, communities of practice, patient flow, and service transformation.

THIS Institute (The Healthcare Improvement Studies Institute)

Ellen supported the production of the series during 2020–21.

About the Series

The past decade has seen enormous growth in both activity and research on improvement in healthcare. This series offers a comprehensive and authoritative set of overviews of the different improvement approaches available, exploring the thinking behind them, examining evidence for each approach, and identifying areas of debate.