Introduction

Bangladesh is an important South Asian country which has been neglected by political scientists and scholars of international security. This inattention is puzzling. With an estimated population of 164 million, 90% of whom are Muslim, Bangladesh is the eighth most populous country in the world and is home to about 10% of the world's Muslim population (Pew 2017; CIA 2021). Additionally, year after year, it is a top contributor of military and police forces to United Nations Peacekeeping Missions. As of October 2021, it was the largest contributor with 6,358 personnel deployed (United Nations 2021). Furthermore, Bangladesh hosts some 900,000 registered Rohingya Muslim refugees who escaped multiple waves of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar in a crowded warren of temporary, unplanned, and exposed refugee camps spread across 34 camps near the Bangladesh–Myanmar border. When one includes those who are not registered, the number of Rohingya in Bangladesh exceeds one million. With the February 2021 coup d'etat in Myanmar, prospects for a voluntary return to Myanmar are slim (Inter Sector Coordination Group 2020; 2021).

Of ostensible concern to social scientists, Bangladesh remains a site of competition between Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and the Islamic State (IS), both of which have perpetrated several attacks in Bangladesh using local cadres over the last 15 years. Pakistani-backed and based groups such as Lashkar-e-Tayyaba (LeT) and its various front organizations have also operated in and from Bangladesh at various times (Montero Reference Montero2010; Khan Reference Khan2017). Additionally, numerous Bangladeshi Islamist groups have operated in the country for decades (Fair et al. Reference Fair, Hamza and Heller2017; Lorch Reference Lorch2020). Despite both the significance of the country and the perduring presence of Islamist militant groups in it, there have been few empirical efforts to understand who supports terrorism in Bangladesh and why (Fair et al. Reference Fair, Hamza and Heller2017). We suspect this inattention is due to the paucity of publicly available, respondent-level data for the country apart from those surveys fielded by Pew. Pew, which aims to provide information about many countries using a common survey over time, consistently queries support for suicide attacks. There is evidence that suggests that this question, denuded of information about the attackers' identity, goals, or targets, elicits unstable preferences (Kull et al. 2007). This is in addition to concerns surrounding the integrity of Pew data (Bohannon Reference Bohannon2016; Kuriakose and Robbins Reference Kuriakose and Robbins2016). In this study, we are well-placed to cast light upon the lineaments of popular Bangladeshi support for both the goals and means of three contemporary Bangladeshi terrorist groups using novel survey data which were collected specifically for this purpose.

In this study, we employ regression analysis of survey data derived from a 2017 nationally representative, face-to-face survey of 4,067 Bangladeshis, fielded in Bangladesh's national language (Bangla). We derive our dependent variables from measures of public support for three terrorist organizations' stated goals as well as the violent means employed in three actual attacks in Bangladesh. Our covariates, derived from a review of the germane literature on individual support for Islamist violence, include participation in communal Friday prayer at a mosque as well as indexed measures of other pietic practices; beliefs about and preferences variously for the scriptural literalism of Shari'a as well as secularism; gender; in addition to several well-established control variables. In general, we find that participation in communal Friday prayers significantly correlates with diminished support for militant groups while having no effect upon support for their violent means. In four (of 10) models, we find that respondents who view Shari'a as being coterminous with scriptural literalism and harsh physical punishments are significantly more likely to support the groups' goals. We find women to be consistently more likely to support the goals and means of the militant groups.

We organize the remainder of this essay as follows: First, we briefly discuss the recent history of Islamist political violence in Bangladesh. Second, we review the germane literature on individual support for Islamist violence to draw out five testable hypotheses. Third, we describe the data and our empirical strategy. We then review our findings and conclude this essay with the implications of our analysis.

Background on Islamist Violence and Communal and Sectarian Strife in Bangladesh

There are several Islamist militant groups that have operated in the recent past or are currently operating in Bangladesh. Harkat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami Bangladesh (HuJI-B) was founded in 1992 and facilitated the development of many other Islamist groups in the country. HuJI-B is widely believed to be behind some of the earliest Islamist terrorist activities in Bangladesh, including the 1993 death threats against the feminist author Taslima Nasreen as well as attempts to assassinate Shamshur Rahman, a famed secular poet, and Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. This group was not included in the survey because it had not been active at the time, though by October 2019, it began to revivify (Hasan Reference Hasan2011; Roul Reference Roul2019; Lorch Reference Lorch2020).

The Jamaat-ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) is an indigenous, Bangladesh-based militant group which coalesced in 1998. The Jagrata Muslim Janata Bangladesh (JMJB) was once distinct from the JMB; however, the two groups merged after Shaikh Abdur Rahman and Siddiqur Rahman (also known as “Bangla Bhai”) began leading both groups. It is most well-known for its August 2005 attack when the group detonated 459 bombs simultaneously in 63 of Bangladesh's 64 districts to coerce the country to adopt Shari'a law. The group is linked to recent violence in Bangladesh and in India (Fair and Abdallah Reference Fair and Abdallah2017; Khan Reference Khan2017; Mazhar Reference Mazhar2020). Arrest data suggest that its leaders tend to be “educated in technical and vocational training colleges and born and raised in urban areas” (Riaz and Parvez Reference Riaz and Parvez2018).

The Ansarullah Bangla Team (ABT) is affiliated with Al-Qaeda and draws its inspiration from one of its former leaders, the late Anwar al-Awlaki. The organization first appeared in 2007, but it did not draw significant attention until 2013 when it began viciously attacking secular writers and bloggers. ABT tends to draw recruits from Bangladesh's middle class, educated youths. The government banned it in May 2015 but remains active under the name of Ansar al-Islam, which the government subsequently banned in 2017 (Riaz Reference Riaz2016; Khan Reference Khan2017). The group continues to operate despite the bans.

In addition to these Bangladesh-based groups, there are several regional Islamist militant groups that operate in Bangladesh such as the Pakistan-based LeT and its various front organizations, including Jamaat-ud-Dawa and Falah-e-Insaniat Foundation (Khan Reference Khan2017). Two trans-national groups, AQIS and IS, have also become increasingly active in Bangladesh in recent years. AQIS has taken responsibility for numerous murders, including murders of secular publishers and bloggers. IS has taken responsibility for other attacks on foreigners, gay people, Shia, Ahmadis, Sufis, and religious minorities, among others. In July 2016, several Bangladeshi terrorists attacked Dhaka's Holey Artisan Bakery killing 20 people over the course of more than 12 h. The attackers were in touch with the IS and dedicated the attack in their name, although there is no evidence that the IS aided or abetted the terrorists in question (Fair and Abdallah Reference Fair and Abdallah2017; Khan Reference Khan2017). In recent years, dozens of Bangladeshi nationals have joined Da'esh (ISIS). In 2016, the group's English-language magazine Dabiq offered a tribute to a Bangladeshi militant who died in Syria (Dabiq 2016; Khandake Reference Khandake2016).

Drivers of Individual Support for Islamist Violence: What the Literature Says

The body of scholarly literature examining support for violent groups has traditionally focused on ethnic conflicts (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1985); state repression (Scott Reference Scott1976); grievances (Gurr Reference Gurr1970; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1981; Ross Reference Ross1993; Hafez Reference Hafez2003; Treistman Reference Treistman2021); the discredited Clash of Civilization thesis (Huntington Reference Huntington1993; Reference Huntington1996); and myriad studies of individual-level explanatory factors and motivations such as, inter alia, piety or other aspects of personal religiosity; preferred level of religious influence on political systems; beliefs about and tastes for democracy; political or social beliefs; participation in communal religious practices, among other germane personal attributes (e.g., Tessler and Nachtwey Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998; Tessler and Robbins Reference Tessler and Robbins2007; Clingingsmith et al. Reference Clingingsmith, Khwaja and Kremer2009; Ginges et al. Reference Ginges, Hansen and Norenzayan2009; Shafiq and Sinno Reference Shafiq and Sinno2010; Chiozza Reference Chiozza2011; Blair et al. Reference Blair, Christine Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2013a; Reference Blair, Lyall and Imai2013b; Ciftci et al. Reference Ciftci, O'Donnel and Tanner2017; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Littman and Nugent2018a; Arikan and Bloom Reference Arikan and Bloom2019). Here we review this considerable literature, informed by specialized knowledge of Bangladesh, to identify five testable hypotheses.

Participation in Communal Religious Practices

There is a growing and substantial literature that examines the effects of participating in communal religious practices upon political motivation and beliefs across faiths, employing different research methods and empirical commitments. Arikan and Bloom (Reference Arikan and Bloom2019), using data from the World Values Survey, found that involvement in religious social networks fosters individuals' propensity to protest. Calhoun-Brown (Reference Calhoun-Brown1996) found that among African Americans, attending a political church was a strong predictor of political involvement and motivation to engage in political concerns. Harris (Reference Harris1994), studying religion and political behavior among African Americans, found that participation in church acts as both a psychological resource for individuals and facilitates collective action by decreasing the transactional costs of organizing (see also Layman Reference Layman1997; Jones-Correa and Leal Reference Jones-Correa and Leal2001). Campbell (Reference Campbell2004), in his study of evangelical Christian political behavior, found that the tight social networks formed through intensive church participation and other church-related activities facilitate rapid and intense political mobilization.

Clingingsmith et al. (Reference Clingingsmith, Khwaja and Kremer2009) studied Pakistanis who undertake the Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) to exposit how participation in the Hajj effected communal, sectarian, and ethnic attitudes. They found that Hajjis (those who did the Hajj) were more inclined toward peace and harmony with non-Muslims, with Muslims of different sects, and different ethnic groups. While undertaking Hajj is correlated with inclinations toward concord among different Pakistanis; Ginges et al. (Reference Ginges, Hansen and Norenzayan2009), using survey data for Palestinians, found that attending communal religious services positively correlated with support for suicide attacks, likely because it enhanced coalitional commitments among attendees. They also studied the impact of participating in regular religious service in six religions across six countries and found that while regular, individual prayer had no impact upon beliefs about martyrdom or out-group hostility, attending communal religious services did. Hoffman and Nugent (Reference Hoffman and Nugent2017), using survey data from Lebanon, found communal prayer increased individual support for arming political parties among those groups engaged in conflict while religious practice tended to foster opposition to militarization among non-combatants. They propose that communal religious practice increases the salience of group interests both through informational mechanisms as well as identity formation.

Ahsan Butt (Reference Butt2016) examined the impact of communal Friday prayers upon street mobilization in the large Pakistani port city of Karachi. He found that street mobilizations were far more likely on Friday than any other day of the week. One of the reasons Butt proposes for this is the content of the khutba, or Friday prayer sermons.Footnote 1 It is common for Friday sermons to be provocative. Sometimes they focus upon international actors (i.e., various U.S. invasions of Muslims countries, Israeli oppression of Palestinians, various European papers' publications of cartoons of the Prophet, France's ruling on Islamic head coverings, etc.). At other times, the khutba may focus upon domestic political actors or issues (the government, the government opposition, specific policies such as the content of curricular or textbook reforms, sales of alcohol, etc.). The khutba may dilate upon conflicts with sectarian or communal minorities such as the Ahmadis, Sufis, Hindus, etc.Footnote 2

While the general literature reviewed above suggests that participation in Friday communal prayers may increase individual support for Islamist militant groups' goals or means, Bangladesh is one of many countries which has sought to regulate the content of khutba as a tool to mitigate Islamist violence. Prime Minister Hasina has long worried about Islamist extremism in her country in part because of HuJI-B's attempt to assassinate her. Following the IS' Holey Bakery attack in July 2016, Hasina's government began regulating these sermons across hundreds of thousands of mosques in the country. Her government shuttered television channels that promoted ideologies that were sympathetic to that of Islamist militant groups and began monitoring the sermons as well as social media to prevent dissemination of messages in support of Islamist militant groups' goals and means. The government enlisted the state-run Islamic Foundation, which is an oversight group for mosques and religious establishments, to prepare the Friday sermon in the national mosque and asked other mosques to use it as well (Express Tribune 2016, also see U.S. Department of State 2018). Additionally, in December 2015, the country's ulema issued a specific fatwa (religious decree) against the IS to counter the threat it posed. According to Maulana Fariduddin Masoud, chairman of Bangladesh Jamiatul Ulama (BJU), a national body of Islamic scholars in the country, “The fatwa is to be jointly signed off by 100,000 Islamic scholars from across the country…It identifies IS and its local Islamist militant supporters—who are killing people and indulging in terrorist activities in Bangladesh and elsewhere—as not just the ‘enemies of Islam’ but also ‘enemies of the Muslims’” (Asian News 2015). Moreover, the BJU took the lead in organizing and training clerics and scholars to support the fatwa and take the campaign to the grassroots level.

Bangladesh is not the only country to attempt to regulate the content of khutba to align it with state goals: states across the Middle East and North Africa as well as Central, South, and Southeast Asia have also done so (e.g., Wiktorowicz Reference Wiktorowicz1999; Epkenhans Reference Epkenhans2009; Errihani Reference Errihani2011). Niger, since 1974, has done it with varying degrees of success over the ensuing decades and regimes (Elischer Reference Elischer2015). In Iran, the government determines the content of the khutba and clerics are directly employed by the state while marginalizing or even prosecuting dissident clerics in the Special Court for Clerics (Tezcür Reference Tezcür2012, 124). Turkey has variously regulated Friday prayers to promote Islamist populism and violence under Erdoğan (Yilmaz and Erturk Reference Yilmaz and Erturk2021) as well as Kemalist secularism (Köker Reference Köker2010). Malaysia too has developed legal and administrative infrastructure to shape the ways in which Malaysians understand Islamic law itself including exclusive control over all existing mosques and the erection of new ones, the appointment and discipline of imams (religious leaders) while federal and state agencies dictate the content of Friday sermons (Moustafa Reference Moustafa2014).

While such efforts may be popular among governments seeking to assert control over religious activities, there is limited evidence attesting to the efficacy of these efforts much less evidence of salubrious impacts upon individuals. After all, persons who distrust state-sponsored khutba can always choose not to attend or, where possible, find alternative arrangements beneath the prying eyes of the state. Conversely, those who do attend may do so because they support the state's effort. Equally notable are the conclusions of Henne (Reference Henne2019), who combined data from the Religion and State Round 3 (RAS3) dataset, which provides measures of several types of government control over religious institutions, and data from the Global Terrorism Database's (GTD), which measures the impact of government interference upon incidence of terrorism, to study the effects of the former upon the latter. He finds that government efforts to exert control over religious institutions increase the incidence of terrorism. This finding complements that of Saiya and Scime (Reference Saiya and Scime2015) who present evidence that religious terrorism derives from a paucity of religious liberty.

Because it is not obvious a priori what—if any—correlation may obtain in the case of Bangladesh, we posit the following Hypothesis:

H1: Participation in Friday prayer is not correlated with support for the goals or means of Islamist militant groups, ceteris paribus.

This discussion requires an additional caveat: in South Asia, as a rule, women do not pray in mosques. Since most mosques do not have reserved places for women to pray inside, the rare woman who chooses to participate must pray upon carpets which are distributed outside of the mosque and endure the immodesty of this arrangement. This does not mean that women cannot listen to the khutba. In Bangladesh—as is the norm throughout South Asia—mosques loudly broadcast the khutba through speakers and/or other public address systems. Both because mosques tend to be small and distributed across the localities they serve and because they employ such public-address systems, many women can hear the khutba, despite the distance and the often-garbled nature of the sound. They may also hear second-hand accounts of the contents of the khutba from the male household members who attended. They may also perform their prayers albeit in privacy or with other female household members. Nonetheless, most women will not experience the communal aspects of Friday prayer in a mosque. Our survey data comport with this general phenomenon in South Asia: only 11 of the 1,752 who attended congregational Friday prayers were female.

Piety and Support for Islamist Militancy

Despite some lingering enthusiasts for Samuel Huntington's “clash of civilizations” thesis (Huntington Reference Huntington1984; Reference Huntington1993; Reference Huntington1996), which posits a fundamental conflict between the Christian West and the so-called Islamic World and asserts that Muslim support for Islamist violence is moored in adherence to Islam itself (Laqueur Reference Laqueur1999; Stern Reference Stern2003; Mendelsohn Reference Mendelsohn2005), as Jonathan Fox (Reference Fox2005, Reference Fox and Haynes2021) observed, most empirical studies of support for Islamist violence find little association between simply believing in Islam and supporting violent politics (Tessler and Nachtwey Reference Tessler and Nachtwey1998; Esposito Reference Esposito2002; Tessler and Robbins Reference Tessler and Robbins2007; Clingingsmith et al. Reference Clingingsmith, Khwaja and Kremer2009; Ginges et al. Reference Ginges, Hansen and Norenzayan2009; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2012; Ciftci et al. Reference Ciftci, O'Donnel and Tanner2017; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Littman, Malhotra and Shapiro2018b; Piazza Reference Piazza2021). In fact, several studies using different data and research methodologies consistently find that Muslim respondents who described themselves as more religiously observant were less supportive of Islamist militant groups and/or Islamist violence (Jo Reference Jo2012; Zhirkov et al. Reference Zhirkov, Verkuyten and Weesie2014; Ciftci et al. Reference Ciftci, O'Donnel and Tanner2017; Piazza Reference Piazza2021). At least two scholars have presented limited evidence that individuals with greater knowledge of Islam, obtained through Quranic study groups and other pietic practices, are better able to resist the arguments of militant thought leaders and thus less likely to support Islamist militant politics (Wiktorowicz Reference Wiktorowicz2005; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Goldstein and Hamza2016).

When a positive correlation between embracing Islam and violence does exist, the relationship is driven by a particular understanding or interpretation of Islam and the concomitant personal obligations they believe Islam establishes for Muslims (Haddad Reference Haddad2004; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Malhotra and Shapiro2012; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Littman and Nugent2018a; Berger Reference Berger2019).

This literature gives rise to our second testable hypothesis:

H2: Piety and support for Islamist violence will be uncorrelated, ceteris paribus.

Shari'a and Support for Islamist Militancy

Empirical studies come to mixed conclusions about the posited relationship between preferences for Shari'a and support for Islamist violence. Fair et al. (Reference Fair, Littman and Nugent2018a) identify and tweeze out several factors that are usually collapsed into survey items querying respondent “support for Shari'a.” They found that support for the physical punishment prescribed by Shari'a explains support for Islamist militancy.

Piazza (Reference Piazza2021) has further elaborated upon the connections between support for Shari'a and support for Islamist violence. He theorizes that a person's beliefs about the compatibility of Shari'a and democracy would be a key predictor in respondent support for Islamist militant groups. He employed 2017 survey data from six Arab countries to understand the support for violence perpetrated by the IS. He found that respondents who favor both the implementation of Shari'a and believe Islam is incompatible with democratic principles are more likely to support the IS. In contrast, those who believe that Shari'a is compatible with democracy are significantly less likely to support the IS.

In the context of Bangladesh, Bangladeshi militants make specific appeals to Shari'a generally and Hudood punishments as part of the IS they wish to establish. For these three groups, democracy and Shari'a are not mutually compatible. To achieve their goals of establishing Shari'a in Bangladesh, all the groups under study here have used violence in hopes of coercing the state to abandon its judicial system and democratic character and replace both with Shari'a law and institutions to enforce it (Bhattacharyya Reference Bhattacharyya2017) while generally making no appeals to public service provisions as the Afghan Taliban claim to do.Footnote 3 This discussion gives rise to our third hypotheses:

H3: Preferences for scriptural literalism and support for Islamist violence will be positively correlated, ceteris paribus.

As noted above, Bangladesh's Islamist militant groups have been arguing for a government based upon their interpretation of Shari'a for decades and they have specifically targeted Bangladesh's secularists and liberal activists presumably because they oppose the Islamist agenda of rendering Bangladesh an Islamist state. It is important to understand what secularism means in the Bangladesh context. In Bangla, secularism is reflected in the phrase “dharmo niropekhkhota,” which literally means “religiously neutral.” Sheikh Mujibur Rehman, who led Bangladesh's independence movement, explained that “secularism [dharma niropekhkhata] does not mean absence of religion. Muslims will observe their religion and nobody in this state has the power to prevent that. Hindus will observe their religion, and nobody has the power to prevent that. Buddhists and Christians will observe their respective religions, and nobody can prevent that. Our only objection is that nobody will be allowed to use religion as a political weapon” (Government of Bangladesh 1972, cited by Uddin Reference Uddin2015, 44).

The historical role that the struggle over secularism has played in Bangladesh's civil and not-so-civil society (Khondker Reference Khondker2006) along with the scholarly works discussed above gives rise to our fourth testable hypotheses:

H4: Support for secularism will negatively affect support for Islamist violence, ceteris paribus.

Gendered Support for Islamist Violence

There is a growing and increasingly sophisticated body of scholarship that seeks to explain women's support for religious and political ideologies that undermine women's equality of access to opportunities and/or outcomes, inclusive of violence against women and girls. Setzler and Yanus (Reference Setzler and Yanus2018); Tien (Reference Tien2017), among others, used survey data to understand why some women—overwhelmingly white—supported Donald Trump despite his overt misogyny and appeals to male supremacy. Others have sought to explain why some women support restrictions on women's access to reproductive justice (e.g., Jelen et al. Reference Jelen, Damore and Lamatsch2002; Swank Reference Swank2021), equal rights legislation (Burris Reference Burris1983; Young Reference Young2007), or fundamentalist versions of religious beliefs which actively promote theological justifications for depriving women and girls of equal opportunities and even violence against the same (e.g., Blaydes and Linzer Reference Blaydes and Linzer2008; Gerami Reference Gerami2012). Many of these studies conclude that women derive social capital or other private benefits from supporting policies that undermine the collective interests of women and girls. There is also an ever-growing literature on female direct and indirect participation in the perpetration of violence (inter alia, Parashar Reference Parashar2011; Lahoud Reference Lahoud2014; Pearson and Winterbotham Reference Pearson and Winterbotham2017; Bodziany and Netczuk-Gwoździewicz Reference Bodziany and Netczuk-Gwoździewicz2019; Huey et al. Reference Huey, Inch and Peladeau2019; Sela-Shayovitz and Dayan Reference Sela-Shayovitz and Dayan2019). These studies too draw out the ways in which such participation in violence bestows upon women different forms of agency as well as social capital.

In contrast, there is a paucity of scholarly studies of respondent-level, female support for political violence generally or Islamist violence specifically. In fact, gender remains both under-theorized and under-studied as a potential explanatory factor in support for violence in empirical studies. If scholars include gender as a variable in their empirical studies at all, almost all do so as a control variable rather than a study variable. Depending upon the countries studied, the research methodology employed, the dependent variable selected, and the nature and character of the survey data used in these studies, among other considerations, scholars exposit differing impacts of gender as a control variable. The various scholars who have used Pew's surveys of the Muslim World to study respondent support for suicide attacks that kill civilians find that when gender is statistically significant, males are more supportive than females (e.g., Shafiq and Sinno Reference Shafiq and Sinno2010; Cherney and Povey Reference Cherney and Povey2013; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Hamza and Heller2017; Fair et al. Reference Fair, Hwang and Majid2019). Notable exceptions include Wike and Samaranayake (Reference Wike and Samaranayake2006) and Fair and Shepherd (Reference Fair and Shepherd2006).

Several scholars who have used data from non-Pew surveys to examine support for various kinds of Islamist violence arrive at different conclusions when they include gender as a control variable. LaFree and Morris (Reference LaFree and Morris2012), using START data to study support for anti-American violence in Egypt, Morocco, and Indonesia, found no statistically significant gender relationship while Kaltenthaler et al. (Reference Kaltenthaler, Miller and Christine Fair2015), using a novel 2013 dataset for Pakistan, found females were statistically more likely to support some Islamist terrorist groups than males. Unfortunately, none of these studies dilate upon gender as a significant consideration.

One of the rare empirical studies which include gender as a primary study variable is Afzal (Reference Afzal2012), who used 2008 START data for Pakistan. Afzal sought to exposit the relationship between gender and support for terrorism with education as a mediating variable. Afzal found that as women's education increased, they became less likely to support Islamist violence relative to comparably educated men all else equal. In contrast, uneducated women were more likely than comparably uneducated men to support Islamist militancy, all else equal. However, women in Pakistan are far less likely to be educated than men: 63.9% of females over the age of 10 are illiterate compared to 32.2% of men (Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, n.d.).

Another exception is a study by Fair and Hamza (Reference Fair and Hamza2018) in which the authors employed data derived from a large national survey of Pakistanis fielded in 2011 to exposit the impacts of gender upon support for two militant groups operating in and from Pakistan, namely: the sectarian group Sipha-e-Sahaba-Pakistan (SSP) and the Afghan Taliban. They found that while women were more likely to support the SSP, gender did statistically explain support for the Taliban. They too fail to propose a mechanism through which gender would exert different effects upon support for violence apart from considering the varying opportunity structures afforded by the groups.

Blaydes and Linzer (Reference Blaydes and Linzer2008), in their study of female support for Islamist fundamentalism and concomitant support for practices that are anti-women, posit that women are making a rational trade-off between returns in the labor and marriage markets. Women with fewer labor market options may invest in their attractiveness in the marriage market, in which fundamentalist views may result in better marriage options. Women with greater labor market opportunities may eschew fundamentalism because some behaviors associated with fundamentalism will diminish labor market opportunities (i.e., wearing a face covering). This differentiation is strongest in countries where the disparity between male and female wages is greater. While Blaydes and Linzer are interested in female support for Islamic fundamentalism rather than Islamist terrorist violence, their framework makes a compelling case for including gender as a study variable rather than a control.

Finally, while Littman et al. (Reference Littman, Marks and Zakayo2021) have also sought to theorize gendered differences in support for violence. They put forward a “female guardian hypothesis,” to explain why women are often observed to be aggressive toward outgroups. They contend that “women's psychology can be characterized by social vigilance and indirect aggression (exclusionary attitudes and behavior) when they perceive a communal threat.” Using data from a survey of 6,000 Nigerians they find compelling support for their theory: women were more likely to perceive a threat and those who have such perceptions are more likely to support discriminatory behaviors toward outgroups. While our data do not permit us to test for gendered threat perceptions, there is an extensive literature on the role of South Asian women policing communal boundaries often by controlling women, whose bodies are the bearer of respectability of the family and community, variously defined (Jayawardena and de Alwis Reference Jayawardena and De Alwis1996). In post-colonial South Asia, women continue to be seen as the repositories of religious beliefs and the “keepers of the purity and integrity of the community” (Basu Reference Basu, Jeffery and Basu2012, 4). While some women have mobilized against such communal politics and the salience attached to women's bodies and behaviors, others have derived power from being invigilators of the same.

This discussion prompts the following hypothesis:

H5: Females are more likely to support militant politics, ceteris paribus.

Data and Analytical Methods

Here we describe the data, model, and method we use to test the above-posited hypotheses as well as the empirical methods we use to do so.

The Data

We use a dataset derived from a face-to-face, nationally representative survey of 4,067 Bangladeshis, fielded in Bangladesh's national language (Bangla), by gender-appropriate teams. We conducted this survey under IRB supervision on behalf of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and executed by the RESOLVE NETWORK, under the auspices of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP). Two co-principal investigators (XXX and YYY) led the survey effort, developed the instrument, oversaw the quality control of the translation, identified, and worked with a highly regarded Bangladeshi survey firm (which wishes to remain un-named due to Bangladesh's political environment) to conduct focus groups about the instrument and pre-test it to ensure that it performed as expected. The instrument they developed collected demographic information for the respondents as well as their beliefs about an array of issues including religion, governance, and violent extremism. The firm conducted the survey between April 12 and 30, 2017.

The local contractor employed a stratified random sampling design that was nationally representative at division levels. Bangladesh has eight divisions. Sample ratios were 50% male and 50% female and 75% rural and 25% urban, which are in accord with the 2011 Bangladesh Population Census. The firm defined samples at the division level which were proportionate with the distribution of the population, per the 2011 Census (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics 2015). The survey response rate was 70%, which is comparable to other surveys in Bangladesh which have a recorded response rate of 75%. The study team originally sought to sample 8,000 respondents; however, halfway through the survey effort, local authorities objected to survey questions about the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami (BJeI) and insisted that they be removed as a condition of permitting the study to continue. The team discontinued further enrolments both for scientific reasons and because the distribution of the sample that had been collected was representative of Bangladesh's eight administrative divisions with reference to gender, religion, and urban/rural residence. The original margin of error for the survey with a sample size of 8,000 was about 1.10% at a 5% level of significance. The margin of error for the reduced sample was 1.54% at a 5% level of significance. While the resultant sample is smaller than planned, it is still four times larger than other publicly available surveys, including Pew's Global Attitudes Survey (Pew 2014).

Operationalization of Variables

Dependent Variables

We have five dependent variables. Our first three variables measure respondent support for the goals of three Islamist militant groups in Bangladesh included in the survey, namely: Bangla Bhai, the Al-Qaeda affiliate; ABT; and the IS. To do so, we first presented the respondent with a summary of an actual attack perpetrated by each group. This vignette specifically identified the goals of the attack and the means the group employed. After each scenario, the survey asks respondents whether they heard of the attack prior to this survey; whether they support the stated goals of the attackers; and whether they support the means (see Appendix A for the questions used (Q700–Q709)). The remaining two dependent variables, support for the goals and support for means, are aggregated measures. We do not use support for the means for any singular group because of the meagre support for the violent means.Footnote 4 We coded all five dependent variables as dichotomous, where zero indicates no support at all and one indicates some level of support. The responses of any participant who did not hear about the attack prior to this survey are coded as a missing observation.

Independent Variables

To evaluate the impacts of attending Friday prayer upon support for Islamist violence (H1), we use a survey item (Q051) which specifically queries the respondent “How many times did you pray Namaz in congregation in the Mosque last Friday/Jumma?” We call this variable “Pray Friday Namaz?.” Answers to this question range from zero to a maximum of five. We recode this variable as 0 for any respondent who did not pray Namaz last Friday and 1 if they did pray Namaz last Friday in the mosque at least once.

To evaluate the effects of personal pietic activities, which are distinct from participation in large congregational Friday prayers in a mosque, upon support for Islamist violence (H2), we construct an additive index for piety that necessarily excludes participation in Friday prayer. To do so, we use the following variables: Whether the respondent attends classes for understanding the Quran (Q030); the number of times the respondent prays Namaz anywhere (Q050); and whether the respondent prays “Tahajjud Namaz,” which is a non-obligatory prayer that happens in the early hours of the morning (Q052). We scaled this index to range from 0 to 1 (higher values indicate higher piety).Footnote 5 Note that we also confirmed that the variables that comprise the piety index are not highly correlated with our Pray Friday Namaz variable (The correlations are all under 0.2). This measure of piety reflects private practices that are in addition to attending communal Friday prayers. We created an additional piety measure (Piety2) which combines these practices along with Friday prayer, which we also scaled from 0 to 1 with higher values indicating higher piety. We use this variety for an additional robustness check discussed below.

To evaluate the impact of support for scriptural literalism and physical punishments on the one hand and support for Islamist political violence on the other (H3), we created an additive index of support for scriptural literalism. We did so by taking the average of each response to the following binary questions: Do you favor or oppose death penalty for Bangladesh Muslims who leave the Muslim religion? (Q975); Do you favor or oppose punishments like whippings and cutting off hands for crimes like theft and robbery (Q985); Do you favor or oppose stoning people who commit adultery? (Q990); Some people say a government under Shari'a should use physical punishments to make sure people obey the law. Do you agree or disagree with this? (Q140).Footnote 6 We rescaled this variable from zero to one, where zero represents complete opposition to scriptural literalism and the punishments it prescribes, while one represents complete support for the same.

To assess whether there is any relationship between support for secularism and support for Islamist militancy (H4), we created another additive index for respondent support for secular values using several survey items, namely: In your opinion how much influence should religious leaders have in matters of political governance? (Q915); and Do you favor or oppose giving Muslim leaders such as Imams the power to decide family and property disputes? (Q970).Footnote 7 We transformed both variables such that zero represents support for a large role of religious leaders (Q915) and complete support for giving leaders such roles and where one represents no support at all. This secularism index ranges from 0 to 1 with higher values representing more support for secularism.

Finally, to assess the effects of gender (H5), we use a dichotomous gender variable, which is coded as 0 for males and 1 for females.

We also include three control variables. To proxy socio-economic standing, we use the educational level of the respondent as a proxy as we were concerned about the reliability of both reported income (Moore et al. Reference Moore, Stinson and Welniak2000; Meyer and Sullivan Reference Meyer and Sullivan2003) and expenditures (Meyer and Sullivan Reference Meyer and Sullivan2003; Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Beegle, De Weerdt and Friedman2014). Survey researchers consistently report that respondents are wary of reporting actual income while household respondents may not be knowledgeable about household expenditures. We also included respondent age and whether the person lives in a rural or urban area.

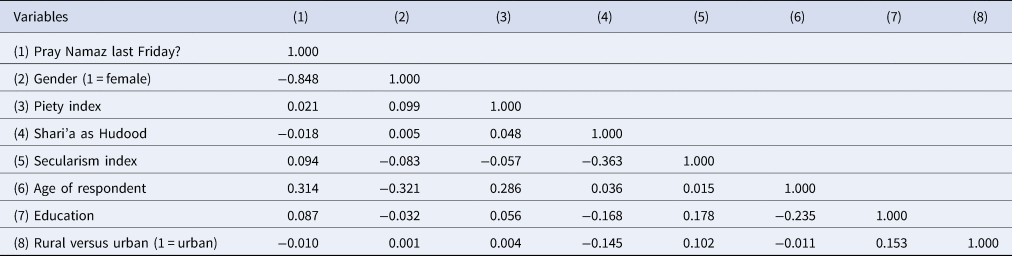

The survey items used in the construction of all variables are available in the Appendix. Below, in Table 1, we present the summary statistics of all dependent, independent, and control variables. Of note is that among the three groups, support for Bangla Bhai's goals is the highest. This may be due to the fact that of the three groups, Bangla Bhai is truly indigenous and is not a partner of either al-Qaeda or IS. Also of note is that overall support for the violent means is extremely low, a full order of magnitude less than support for the goals. In Table 2, we provide a correlation matrix for our independent variables.

Table 1. Summary statistics of variables

Source: In-house tabulations of survey data.

Methods

We estimate two sets of models for each of the five dependent variables. Because women do not attend Friday prayers in our data, gender and participation in communal prayers are highly correlated (see Table 2). For this reason, in one set of models (1a–5a), we include gender while excluding Friday prayer participation. In the other set of models (1b–5b), we include Friday prayer participation while excluding gender. In both sets, our five dependent variables are: support for the goals of Bangla Bhai, support for the goals of Ansar Bangla Team, support for the goals of the IS; a combined measure of support for any of the goals of any of the three groups and a combined measure for support of the means employed by any of the three groups.

We include in each model the above-noted independent variables and controls for the age and education of the respondent and whether the respondent lives in an urban area. We estimate the models using division fixed effects for a dichotomous dependent variable using a logit link. We estimate:

where p ij represents support for goals or means (or the probability that the dependent variable equals 1) for individual i in district j, αi represents the fixed effects, and r ij represents the error term.

As a robustness check, we estimate another set of models in which we use Piety2 (an index that combines the piety index and Pray Friday Namaz), described above. In this model, we run Piety2 and gender as well as the other variables noted above. As the correlation matrix for these independent variables shows, this is justified because gender is not highly correlated with Piety2. We estimate another version of this model for females only.

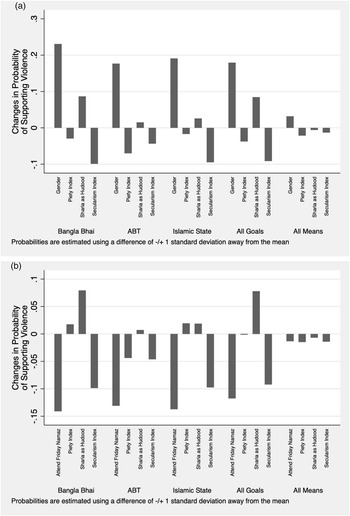

We place estimates for Models 1a–5a and 1b–5b in Tables 3 and 4 below.Footnote 8 We place estimates for Models B1–B5 in Table B21 in Appendix B (Table B2) as well as the correlation matrices for all independent variables used in those models (Table B1). The estimates for the female-only respondent model are also in Appendix B (Table B3). For ease of interpretation, we also depict predicted probability for each variable for both sets of models. Doing so permits us to compare the impact of each variable with each other. In Figures 1a and 1b, we depict the change in predicted probabilities of each variable, when its value is taken at +/− one standard deviation away from the mean while holding all other variables constant at their mean. Figure 1a is based upon the estimations for Models 1a–5a whereas Figure 1b is based upon the estimations of Models 1b–5b.

Figure 1. (a) Changes in probability of supporting violence in models that include gender (Models 1a–5a). Source: In-house tabulations of survey data. (b) Changes in probability of supporting violence in models that include Friday prayer (Models 1b–5b). Source: In-house tabulations of survey data

Table 3. Estimates for Models 1a–5a

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Table 4. Estimates for Models 1b–5b

Standard errors in parentheses.

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Discussion of Results

How do these empirical results compare with our hypothesized relationships? We find mixed support for H1, which posited no relationship between support for militant politics and attending Friday prayer. As the estimates in Table 3b show, participation in Friday prayer is significantly (at the 0.001 level) and negatively correlated with every measure of support of militant goals; however, it is insignificant for support of the means.

In H2, we hypothesized that piety and support for Islamist violence will be uncorrelated, ceteris paribus. In all but two models (2a and 4a), this piety measure is uncorrelated with any measures of support. In Models 2a and 4a, the estimates are negatively correlated with support (at the 0.05 significance level). These estimates provide compelling evidence that both measures of piety, the indexed measure and attending communal prayers, do not increase support for militant politics. If they have any impacts upon support, it is negative. As noted, we also ran an additional set of models as a robustness check which used Piety2 and the other covariates, including gender. As the results in Appendix B show, this is a consistent finding.

In H3, we argued that persons with higher preferences for Shari'a and the physical punishments prescribed by scriptural literalism will be more likely to support the goals and means of the militant groups in question, ceteris paribus. Our estimates provide mixed support for this claim: in Models 1a and 1b (support for the goals of Bangla Bhai) and Models 4a and 4b (combined measure of support), higher preferences for Shari'a are positively correlated with support (at the 0.001 level). In the other three models, the coefficients are also positive, but they are not statistically significant. We find no correlation with support for the groups' violent means in any model.

In H4, we proposed that support for secularism will be negatively correlated with support for Islamist violence, ceteris paribus. Our estimates provide considerable support for this claim. In six models (1a, 1b, 3a, 3b, 4a, 4b), secularism is negatively and significantly (at the 0.001 level) correlated with measures of support for the groups' goals.

In H5, we asserted that females are more likely to support militant politics, ceteris paribus. Our estimates in Table 3a provide strong and significant support for this claim. In all models, females are significantly more likely to support militant groups' goals (at the 0.001 significance level) and violent means (at the 0.01 significance level), despite the overall low level of support for the means. To further understand and evaluate female support for the goals and means of the groups in question, as described above, we ran an additional model for female-only respondents and Piety2, the combined piety index. This is appropriate because gender is not highly correlated with this measure even though it is highly and negatively correlated with the attendance of Friday prayer. As the results in Appendix Table 3b show, in this model, variation in the piety index does not significantly explain variation in the dependent variables. Support for Shari'a significantly correlates with support for the goals of Bangla Bhai (at the 0.001 level) and IS (at the 0.05 level) as well as the combined measure of support for the goals (at the 0.001 level). Secularism is a significant and negative predictor of support for the goals but not the means. Age in most models for support of the goals negatively and significantly correlates with support of goals but not means and education is negative in significance in explaining support for the goals of ABT and the IS.

In Figures 1a and 1b, we present the changes in predicted probabilities of supporting the goals and means for each variable evaluated at +/− one standard deviation away from the mean while holding all other variables constant at their mean. We created Figure 1a from the estimates for Models 1a–5b, which includes gender but excludes Friday prayer attendance. Figure 1a demonstrates that the variable with the biggest impact on supporting the goals of the militant groups (Models 1a–4a) is gender. We derive Figure 1b from estimates for Models 1a–5b, which includes Friday prayer attendance but excludes gender. As the data in Figure 1b show, Friday prayer attendance has the biggest impact on supporting the goals of violence (Models 1b–4b).

Implications and Conclusions

Many of our findings align with extant scholarship. Piety is generally uncorrelated with any measures of support and when it is correlated, it is negative. We find mixed support for the notion that Shari'a and the physical punishments prescribed by scriptural literalism will correlate with higher support for militant politics. In several models, higher preferences for Shari'a are positively correlated with support of group means (at the 0.001 level) while in the remainder, the coefficients are also positive, but they are not statistically significant. We find no correlation between support for Shari'a and support for the groups' violent means in any model. In contrast, in several models, we find that support for secularism is associated with diminished support for group goals while having no impact upon support for means. Among the controls, age and education are significantly and negatively related to support for group goals in most models.

Overall, in our sample, support for the goals of the three terrorist groups range from 28% for ABT to 38% for Bangla Bhai with about 42% of the sample supporting the goals of least one group. However, support for the means is much lower with less than 8% supporting the means for at least one group. This is considerably lower than Pew's measure of support for suicide bombing among Bangladeshis which has ranged from 47% in 2014 to 44% in 2002. In fact, Bangladeshi respondents consistently are among the most supportive populations surveyed by Pew (Fair et al. Reference Fair, Hamza and Heller2017). While registering high levels of support for “suicide bombing and other forms of violence against civilian targets…in order to defend Islam from its enemies,” Bangladesh has experienced only 12 confirmed suicide attacks between November 2005 and October 2018 out of over 5,030 suicide attacks that occurred globally in the same period (Global Terrorism Database). The relatively high support for this tactic—denuded of politics—may in fact be high because so few suicide attacks have occurred in Bangladesh (Michael and Scolnick Reference Michael and Scolnick2006; Fair Reference Fair2009; Pew Research Center 2013).

While several findings align with previous studies, there are two significant findings from the study that merit further study. First, attendance of Friday prayer is strongly correlated with diminished support for militant goals. This measure differs from other pious activities because it is communal. Bangladesh under Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, like many other Muslim-majority states, has co-opted Islamic institutions to institute the Friday sermon as an explicit messaging opportunity to delegitimize the goals and violent means of Islamist militant groups. It may be tempting to conclude that the state efforts to regulate khutba content explain this diminished support for the groups' means; however, such an inference is premature. This result may also derive from a selection effect: those who agree with the government's instrumentalization of khutba content may attend Friday prayer disproportionately more often than those who oppose it. This finding is in stark contrast to extant work which generally finds that participation in communal religious activities is correlated with increased support for militant politics. We cannot unpack the causal mechanism for this finding with extant data. Understanding the nature of this correlation and any putative causality would likely require extensive observation of a significant sample of khutba across Bangladesh and coding of their contents as well as interviews with attendees. Another empirical strategy may involve a random assignment of individuals to attend a khutba which is known to be regulated following a methodology similar to that of Clingingsmith et al. (Reference Clingingsmith, Khwaja and Kremer2009). Alternatively, ethnographic study methods may also provide some insight into the same or a similar survey which explicitly queries respondents about their knowledge of and support for the government's effort to use the khutba as a strategy to counter violent extremism.

The second important finding is that women are significantly more likely to support militant goals and violent means than are men. Much of the cited literature suggests reasons why women may do so; however, with these data we cannot proffer a causal pathway that accounts for this finding. Our findings are consistent with the “female guardian hypothesis” proposed by Littman et al. (Reference Littman, Marks and Zakayo2021) as well as by the framework of Blaydes and Linzer (Reference Blaydes and Linzer2008). The estimates for our female-only model find that as education increases (in two models), support for militant goals decreases, which also aligns with Blaydes and Linzer (Reference Blaydes and Linzer2008).

Curiously, Fair et al. (Reference Fair, Hamza and Heller2017), using 2011–2012 data for Bangladesh from Pew's World's Muslims Data Set, found that men were more likely to support suicide bombing. In fact, most scholars who have used Pew data and control for gender find that men are more likely to support the tactic. It is not clear how much significance we should attach to the findings about this question for at least three reasons. First, Kull et al. (Reference Kull, Ramsay, Weber, Lewis, Mohseni, Speck, Ciolek and Brouwer2007) report that this question, denuded of politics, does not yield stable preferences. Second, it is likely that support for the tactic is higher in a country which has little experience with its brutalities. Third, scholars who use other survey data to query support for more highly specified terrorist attacks come to different conclusions as well. What is clear is that the females in our survey are more likely than men to support both the goals and means of the three terrorist groups in our survey. Future surveys of Bangladesh or other countries may wish to include the Pew question on suicide attacks for benchmarking purposes but querying about groups and attacks that are relevant to the populations being surveyed may be a more productive avenue of inquiry.

Unfortunately, there are few studies that posit explanations for gendered support for militant politics. However, there are several reasons why scholars should consider gender as a study variable. Since the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States and the concomitant spread of Islamist terrorism, many governments have pursued what can be called “counter-violence extremism” programming. Such programming tends to focus upon the “males of military age” in the hopes of deterring them from embracing violent politics or perpetrating acts of violence. This overt focus upon males disregards the important roles that women play as the primary care provider of children and their considerable influence in their children's decisions to actively or passively support violent politics. Some groups such as LeT even demand that operatives secure the blessings of their mother before they are dispatched upon operations (Abou Zahab Reference Abou Zahab, Rao, Bollig and Bock2007; Haq Reference Haq2007; Fair and Hamza Reference Fair and Hamza2018; Fair Reference Fair2019). This is in addition to the actual participation of some women in the militant groups themselves (Davis Reference Davis2017; Rinehart Reference Rinehart2019). Indeed, Bangladesh has witnessed the emergence of the female suicide bomber (Mohsina Reference Mohsina2017; Roul Reference Roul2018).

This study buttresses those of Ladbury (Reference Ladbury2015); Afzal (Reference Afzal2012); Fair and Hamza (Reference Fair and Hamza2018); Littman et al. (Reference Littman, Marks and Zakayo2021); as well as Blaydes and Linzer (Reference Blaydes and Linzer2008) and suggest that there is an urgent need to understand the lineaments of female support for Islamist violence both to inform scholarly theoretical and empirical understandings of support for violent politics as well as policy initiatives to counter support for violent extremism.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755048322000116.