Ah! I am fed up with the Eternal City, I feel I have been here for an eternity, and Paris, the people I love, a certain shop in the rue de Rome … all this does not seem to exist any more.

Debussy lived in Paris for most of his life, and apart from summers, which he often spent in seaside resorts such as Houlgate in Normandy, he left the ‘City of Light’ only with reluctance. Even Rome, the ‘Eternal City’, bored him. In many ways, Debussy epitomises the new confidence of the city as a centre of culture and good living. His life embraced both its old bohemian neighbourhoods and the new, smart boulevards that had replaced much of the medieval city in the years before the Commune. This chapter explores the City of Light, the city of the Belle Époque, a chrononym that emerged during the 1930s to single out the three decades preceding the First World War, often seen as a golden age.Footnote 1 From the point of view of its new town plan, its museums, its transport, and its exhibitions, it describes many aspects of the city that Debussy used, such as the local railway, situated close to the end of his garden, and the adoption of the motor car as a means of transport. Technological advances came raining down in these years; they included typewriters, piano rolls, recordings, new music-printing technology, and much more. This chapter will attempt to describe what it was like to live in this city, both for a struggling bohemian artist like the young Debussy and for the established, bourgeois figure of the later years.

From the Quartier de l’Europe to the Grands Boulevards: Debussy and the Modernisation of Paris

The list of Debussy’s Parisian addresses reveals that he lived in neighbourhoods marked by modernisation processes.

Until 1887: 13, rue Clapeyron (8th)

September 1888 to September 1890: 27, rue de Berlin (8th)

October to December 1890: 76, boulevard Malesherbes (8th)

January to May 1891: 27, rue de Berlin (8th)

June to 23 July 1891: 42, rue de Londres (8th)

24 July 1894 to December 1898: 10, rue Gustave Doret (17th)

January 1899 to September 1904: 58, rue Cardinet (17th)

October 1904 to September 1905: 10, avenue Alphand (16th)

October 1905 to 1918: 64 and 80, avenue du Bois de Boulogne [avenue Foch] (16th)Footnote 2

Until 1904, Debussy lived in or near the quartier de l’Europe (rue Clapeyron, rue de Berlin), the realisation of which (1820–39) was one of the most ambitious transformations made in Paris during the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 3 That Debussy moved into the 16th arrondissement in 1904, and the following year into a hôtel particulier located in the avenue du Bois de Boulogne, shows that he had achieved a bourgeois status, since this neighbourhood was the most expensive in Paris. Beyond this evolution, Debussy’s Parisian addresses reveal that he lived in modern parts of Paris and that he could indeed experience the modernisation of the city.

Between 1853 and 1870, Paris underwent the most spectacular renovation plan of its history. In order to reduce the spread of diseases and the criminality rate in a then overcrowded city, and to facilitate communications and interventions by the police and army troops in case of uprisings or revolutions, Napoleon III elevated Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann to préfet of the Seine, with the mission to carry out an impressive programme that completely transformed the central districts of the French capital, the plan of which had not changed significantly since medieval times. His new plan was based on the grande croisée de Paris, a grand, cross-facilitating east-west and north-south communication. This led to the creation of the rue de Rivoli, the boulevard de Sebastopol, and the boulevard de Strasbourg. In 1859, an official parliamentary report could boast that these first renovations works had ‘brought air, light and healthiness and procured easier circulation in a labyrinth that was constantly blocked and impenetrable’.Footnote 4 A second phase comprised the creation of a network of new boulevards (e.g. boulevards Magenta, Malesherbes, and Debussy’s boulevard du Bois de Boulogne, constructed in 1854), which were meant to connect the centre of Paris with the already existing boulevard ring built under Louis XVIII. This programme went hand in hand with the creation of squares, which served both as connecting nodes for the new boulevards and as a way to create more public spaces, such as the place de l’Étoile, the place du Château d’Eau (today place de la République), but also public parks for leisure and hygiene purposes, such as the parc Monceau, the parc des Buttes-Chaumont, and the Bois de Vincennes.

Facilitating communication inside the city was crucial, since in 1860, with the annexation of the suburbs, then composed of eleven communes (Passy, Auteuil, Batignolles, Montmartre, La Chapelle, La Villette, Belleville, Charonne, Bercy, Grenelle, and Vaugirard), Paris doubled in size. It now included all areas circumscribed by the Thiers walls built between 1841 and 1844.Footnote 5 Throughout his life, Debussy thus lived in a fortified city and it was not until 1919 that the Thiers wall was progressively demolished and replaced by the ring road we know today as the boulevards des Maréchaux, each segment being named after a First Empire marshal.

The expansion of Paris also raised the question of public transportation. The first tramway service (horse-cars) was created by Haussmann in conjunction with his renovation plan. It was augmented with the Chemin de fer de Petite Ceinture (1852–9) which, in the 1860s, was mainly used by workers. It peaked during the 1900 Exposition Universelle (also known as the 1900 Paris Exposition, a World’s Fair), before being progressively abandoned in favour of engineer Fulgence Bienvenüe’s Métropolitain, which entered into service during the Exposition.Footnote 6

The plan of the Parisian subway was an underground reproduction of the map of Paris and reflected the importance of modern arts in the French capital,Footnote 7 since Hector Guimard’s édicules made for the entranceways were heavily influenced by Art Nouveau. Until his death in 1918, Debussy witnessed the birth of ten Métro lines, which transported a total of 467 million people in 1913, the year during which hippomobile tramways and omnibuses were replaced by motorised transportation.Footnote 8 No doubt Debussy was interested in these changes, which also aroused the curiosity of Joris-Karl Huysmans, who depicted an omnibus drive in a chapter of his Croquis parisiens,Footnote 9 one of Debussy’s favourite readings during his stay at the Villa Medici.Footnote 10

The 1900 Exposition Universelle was also key to the modernisation of Paris’s public transportation system in that it hosted the first Congrès international d’automobilisme. The simultaneous appearance of the subway network and motor cars marked a dramatic evolution and the dawn of a modern era for Paris. In 1900, there were 618 registered private cars in Paris, and most of the owners lived in the 8th, 9th, 16th, and 17th arrondissements,Footnote 11 all of which were part of Debussy’s daily life. Seven years later, the number of cars had multiplied by ten, in addition to autobuses, which began service in 1906. This development brought important changes in the French capital. From then on, new streets were to be adapted to the circulation of cars while preserving the cachet of Parisian urbanity.Footnote 12 Pedestrian movement had to be controlled in order to avoid congestion and accidents. Stefan Zweig wrote: ‘Paris has become frightening … the stink of petrol invades the streets, and crossing them is now an adventure.’Footnote 13

The Paris in which Debussy lived was certainly a city marked by spectacular modernisation processes, but what about Debussy’s Paris – his own experience of the city? In his correspondence, he does not speak much about the way he gets from one place to another. However, in the 1890s and before his move to the 16th arrondissement, he frequently mentions cafés and brasseries where he meets his friends and takes lunch or dinner. Most of these cafés were located in or next to the quartier de l’Europe – for example, the Café Passerelle, in the Saint Lazare railway station; and the Brasserie Mollard (rue Saint Lazare), where he used to meet his close friend Pierre Louÿs (1870–1925). Debussy’s frequentation of cafés also served the purpose of artistic discussions and networking. In the late 1880s and 1890s, he regularly met friends and artists at the Brasserie Pousset, then the Parisian hub of the Symbolist group comprising the poet Catulle Mendès, playwright René Peter, painter Paul Robert, fellow composer André Messager, and actor André Antoine, director of the Théâtre Libre. Two other Symbolist gatherings were the ‘Mardis de Mallarmé’ in the poet’s apartment (rue de Rome) and Edmond Bailly’s Librairie de l’Art indépendant (rue de la Chaussée d’Antin) close to the quartier de l’Europe, where Debussy met writers such as Henri de Régnier, Paul Claudel, and André Gide. At the Librairie, he also often played new music (both popular and art repertoires), together with his fellow composer Erik Satie (1866–1925). The latter was the link between Debussy’s two Parises – the modern one, where he lived, and Montmartre, where they met, thanks to their common taste for café-concerts. Debussy often went to the Chat NoirFootnote 14 and also, at the bottom of the Butte (avenue Trudaine, where Maurice Ravel and Ricardo Viñes often came in the 1890s to play at Emmanuel Chabrier’s apartment), L’Âne Rouge and the Auberge du Clou, where he performed with Satie. Debussy’s La plus que lente (1910) can be heard as a souvenir of café-concerts, as well as his ‘La Belle au bois dormant’ (1890), to a poem by chansonnier Vincent Hyspa. One last important location in Debussy’s artistic Paris was the salon of Marguerite de Saint-Marceaux (boulevard Malesherbes), where he could meet fellow composers Ravel, Chabrier, Gabriel Fauré, and Reynaldo Hahn, among others. Saint-Marceaux’s hôtel particulier was close to his apartments before 1904 and later his house in the avenue Foch was directly connected to it via the Arc de Triomphe. This proximity between Debussy’s homes up to 1904 and the venues he frequented on a daily basis can be explained by the fact that, until 1900, most Parisians were pedestrians and thus lived in the quartier where they worked rather than in the entire city.Footnote 15

From the Music Hall to the Museum: A Capital of Culture and Leisure Entertainment

One other major aspect of the modernisation of the capital that Debussy could observe and experiment with was the arts and entertainment industry.Footnote 16 That Napoleon III and Haussmann articulated the renovation of the capital’s architecture and urbanism with the development of the arts was illustrated by the presence of two theatres: the Nouveau Théâtre-Lyrique (now Théâtre de la Ville) and the Théâtre du Châtelet, at the crossroad of Haussmann’s grande croisée, which was the new heart of Paris. Another central feature in the plans of Napoleon III and Haussmann to enhance the prestige of the renovated city was the construction of a new building to host the Théâtre national de l’Opéra. Designed by Charles Garnier (1825–98), it was inaugurated in 1875. Debussy was a habitué, but used the best of his irony to denigrate both the building and the repertoire: ‘for an unsuspecting passer-by, it [the Opéra] still resembles a railway station; when inside, you could take it for a Turkish bath. Peculiar noise continues to be made therein, which people who have paid for it call this music.’Footnote 17

The Paris in which Debussy lived was a capital where theatre had a central place. Since Emperor Napoleon I’s 1807 law on the rationalisation of theatrical activities in Paris, only six theatres in addition to the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique were officially recognised (Théâtre-Français, Théâtre de l’Impératrice, Théâtre du Vaudeville, Théâtre des Variétés, Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin, and Théâtre de la Gaîté). The creation of any other establishment (for instance, those located on the boulevard du Temple) had to be authorised by the government. This situation spiralled in 1864, when Napoleon III’s decree on the liberalisation of theatres triggered a boom in their construction during Debussy’s early life, including such theatres as the Bouffes Parisiens (1855), where Debussy discovered Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelléas et Mélisande in 1893, and the Bouffes du Nord (1876).Footnote 18 Such an environment must certainly have nurtured his ambitions as, in the 1890s, he aspired to create a literary journal and wrote three comedies together with his friend René Peter.Footnote 19

The circus, which had its French golden age during the 1870s and the Belle Époque, was also part of Debussy’s daily life in Paris. Paris could then boast five permanent circuses, including the Cirque Molier (1880–1933), which was a five-minute walk from Debussy’s hôtel particulier in the avenue Foch.Footnote 20 Circus shows had a double impact on Debussy. On the one hand, he used them as a reference point in his music criticism, as when he compared the attraction instrumental virtuosity had for audiences to the fascination exerted by circus acrobats,Footnote 21 and Strauss’s Till Eulenspiegel to a clown act.Footnote 22 On the other hand, Debussy also loved clowns, which had a direct impact on his music. ‘General Lavine – eccentric’ portrays one of the most famous American clowns in Paris, Edward Lavine. The parody of Wagner’s Tristan in ‘Golliwogg’s Cake Walk’ also stems directly from an act in which a band played tunes from the opera as a comic accompaniment.Footnote 23

In a similar way, Debussy was influenced by the music hall when composing ‘Minstrels’. Developed in London, music hall had its Parisian heyday during the Belle Époque, which was marked by a wave of Anglophilia. Debussy participated in this trend, not only in the French vogue of Pre-Raphaelitism and anglicising the titles of five of the pieces from Children’s Corner, but also by frequenting the Irish and American Bar (rue Royale) and going to music halls.

He witnessed the construction of major French establishments of this type, including the Folies-Bergère (1886), Moulin Rouge (1889), Olympia (1893), and Alhambra (1904). At the Folies-Bergère he saw minstrel acts (Fig. 1.1), which he evoked in ‘Minstrels’ (Préludes, book 1, 1909–1910). Music-hall shows integrated any new type of novelty, artistic or technological, which could have public appeal. This is the reason why, after the first Parisian cinematographic projection organised by the Lumière brothers in the Grand Café (28 December 1895), the cinématographe developed as an attraction within music-hall shows. It was not until 1904 that the first cinemas opened in Paris with the Petit Journal (1904), followed by the Théâtre cinématographe Pathé (1906). The success of this new form of popular entertainment was spectacular, for within a year more than a hundred cinemas had blossomed in the capital. Although Debussy did not write specifically about cinema, it was on his mind, since he compared Richard Strauss’s rapid succession of musical sequences in Ein Heldenleben (1898) to film.Footnote 24

Figure 1.1 Poster promoting Les Marionettes Minstrels at the Folies-Bergère (between 1882 and 1888) [Illustrator unknown], Musée Carnavalet, AFF463.

During Debussy’s life, Paris hosted three Expositions Universelles – in 1878, 1889, and 1900. They contributed to asserting the cultural and economic influence of France in the world. They helped to transform Paris: the Palais du Trocadéro was built for the 1878 edition, the Eiffel Tower was the landmark of the 1889 edition, and the 1900 Exposition gave Paris the Grand Palais and the Petit Palais. They confirmed Paris’s status as one of the most important cultural centres in the world. For Debussy, attending these exhibitions was not just a matter of leisure and curiosity. His visits to the Exposition Universelle of 1889 had at least two major consequences for his artistic evolution, since it brought Russian and Oriental music to the forefront of his musical imagination (though he had already encountered Russian music when he spent two summers, 1880 and 1881, with Nadezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky’s sponsor). Three concerts were organised – one devoted to popular Russian music, and the two ‘Concerts russes’ under the direction of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (1844–1908) at the Palais du Trocadéro. The programme featured works by members of The Five, plus Alexander Dargomyjsky, Alexander Glazunov, Mikhail Glinka, and Anatoly Liadov. Four years after these concerts, in 1893, Debussy could tell the journalist Alfred Mortier (1865–1937): ‘Chabrier, Mussorgsky, Palestrina, those are the ones I like!’Footnote 25 But oriental music was Debussy’s most striking discovery during the 1889 Exposition, notably the Javanese gamelan, presented during dance shows in a reconstituted Javanese village. The experience proved formative for Debussy who, five years later, tells Pierre Louÿs, ‘Remember Javanese music, which contained every nuance, even those that we cannot name any more, where the tonic and the dominant were only vain ghosts for naughty children.’Footnote 26 Pieces such as ‘Pagodes’ (Estampes, 1903) and ‘Le Vent dans la plaine’ (Préludes, book 1, 1910) bear testimony to the influence of Gamelan music on Debussy’s stylistic evolution.

The Exposition Universelle of 1900, which was visited by fifty-one million people, also exerted influence on Debussy and other French composers, including Ravel and Maurice Delage. Debussy discovered ragtime and cakewalks – played by John Sousa’s American band – two genres from which he borrowed characteristic features in ‘Golliwogg’s Cake Walk’ and Le petit nègre. Debussy was also fascinated by the Danseuses de Delphes (a Greek sculpture also known as the Acanthus Column), recently discovered by the École française d’Athènes and exhibited in facsimile in the Pavillon de l’archéologie française. Debussy evoked them in his piano preludes (book 1).

Expositions Universelles were only one part of the cultural policy of the Third Republic, which gave priority to the development of museums. The Musée du Louvre (founded in 1793), the topic of one of Debussy’s piano pieces (‘Souvenir du Louvre’, Images oubliées, 1894), was profoundly renovated and enlarged after suffering from fire and destruction during the Commune (1871). The Expositions coincided with the development of new museums, which were also places of high interest in Debussy’s Paris. He could nurture his passion for the Far East in the two Asian art museums founded during the Belle Époque, in addition to the Musée indochinois, which opened in 1878 in the Palais du Trocadéro. The first was the Musée Guimet, built in 1889 on the place d’Iéna (16th arrondissement). The second, the Musée Cernuschi, was founded in 1898. More broadly, Debussy witnessed a glut of new museums in Paris, with the inauguration of the Musée Carnavalet (1880), the Musée Gustave Moreau (1897), devoted to one of his favourite painters, and the Musée des arts décoratifs (1905). The opening of the latter was a landmark. Like the World’s Fairs, it legitimised the association of art and industry, of artworks and goods.

Technological Advances in Paris: Commodification of the Arts and Artification of Commodities

Debussy’s taste for Japonism and Art Nouveau led him to frequent the shops of art dealers such as Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), whose Maison de l’Art Nouveau played a major role in developing functional art and the accessibility of artworks through technological innovations in the fields of lithography and similigravure.Footnote 27 Debussy bought prints there, and he attended the sale of Bing’s Chinese, Korean, and Japanese collections at the Galerie Durand-Ruel on 5 May 1906.Footnote 28

The trilogy of art, technology, and commerce presided over music printing, which adapted to the emergence of mass culture, epitomised in the rise of the music hall. Publishers like Hachette, Marchetti, and Salabert developed illustrated sheet music in colour, allowing covers to play a similar role to advertisement posters: they used catchy designs and colours, insisted that the songs were already popular successes, and exploited the celebrity of the singers who popularised them.

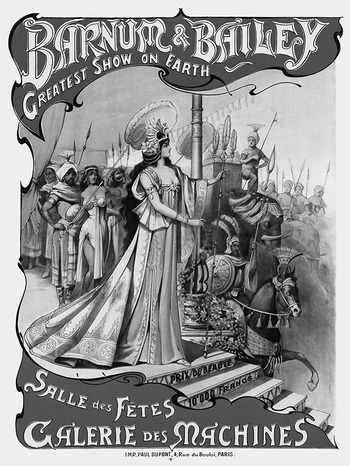

Reciprocally, posters made by Jules Chéret epitomised the blurring of the frontier between artistic works and commodities, between utilitarian goals and aesthetic ideals, in a way similar to Hector Guimard’s édicules. Debussy, whose La Damoiselle élue was published by Bailly’s Librairie de l’art indépendant with an illustration by Nabi painter Maurice Denis (1870–1943), was fond of this type of poster. In 1901, he spent one night ‘beholding the posters of the Barnum Circus (then located on the Champ de Mars); at 3:00 am we had only looked at half of them’Footnote 29 (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Poster of the Barnum and Bailey show (Paris, 1901) [Illustrator unknown], Bibliothèque nationale de France, ENT DN-1 (STROBRIDGE2)-ROUL.

Illustrated sheet music was also used to promote recordings at a time when the recording industry was beginning to prosper. In Paris, the recording industry was first dominated by Pathé, which began selling recordings made by American labels such as Columbia, and from 1896 made its own recordings. The Compagnie française du Gramo-phone followed in 1898. Debussy was well aware of the development of the recording industry, since in 1904 he recorded four 78 rpm discs with singer Mary Garden (1874–1967, the first Mélisande) for the Compagnie française du Gramophone. Unfettered by the restricted range of acoustic gramophone recordings, Debussy could also listen to what was then called musique mécanique on the reproducing pianos (among other mechanical instruments) commercialised by the Aeolian company from 1885 and popularised in France by the Welte-Mignon reproducing piano (1904). This invention consisted of capturing the pianists’ performances on perforated strips. Debussy recorded six piano rolls of this type, containing fourteen of his piano pieces:

WM 2733: Children’s Corner (complete);

WM 2734: D’un cahier d’esquisses;

WM 2735: ‘La Soirée dans Grenade’ (Estampes);

WM 2736: La plus que lente;

WM 2738: ‘Danseuses de Delphes’, ‘La Cathédrale engloutie’, and ‘La Danse de Puck’ (Préludes, book 1);

WM 2739: ‘Le Vent dans la plaine’ and ‘Minstrels’ (Préludes, book 1).

That even Debussy’s performances were for sale shows how new technologies played a decisive role in blurring and redefining the boundaries between art and commodity.

* * *

Paris was never a subject in Debussy’s music, as it was in that of Pierre-Octave Ferroud (Au parc Monceau, 1921), Frederick Delius (Paris: The Song of a Great City, 1900), and George Gershwin (An American in Paris, 1928). However, the city was not just his home; as Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) pointed out, it contributed to shape his artistic culture, perception, and sensorial experience.Footnote 30 More than his city, Paris was Debussy’s world. As such, he interacted with it, and this interaction undeniably bore fruits in his music.

Author’s Recommendation

‘Golliwogg’s Cake Walk’, Children’s Corner (1906–8).

‘Golliwogg’s Cake Walk’ is part of Children’s Corner, a suite that Debussy composed for his daughter Claude-Emma (Chouchou), born in 1905. The association between cakewalk and childhood may be critically understood as a patronising perspective on African-American music and dance. But thinking that way would also imply that Debussy had only condescension for other music traditions conveyed in Children’s Corner (piano exercises in ‘Gradus ad Parnassum’ and Chinese music in ‘Serenade for the Doll’, for instance). The link between cakewalk and childhood came from the famous circumstances of its first Parisian presentation in 1902, in the pantomime Les Joyeux Nègres by Rodolphe Berger, at the Nouveau Cirque. The public was struck by the fact that it starred two children: Rudy and Fredy Walker. Hence Debussy’s association between the cakewalk and Golliwogg, a black child doll from Florence Kate Upton’s The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a ‘Golliwogg’ (1895). This short piece in ABA′ form is also part of a wider French tradition of mocking Wagner and Wagnerism, from Gabriel Fauré and André Messager’s quadrille Souvenirs de Bayreuth (1888) to front pages of satiric journals such as L’Assiette au beurre showing ‘Du caporal Lohengrin’ in the middle of a circus act (22 April 1905). Similarly, Debussy introduces the main leitmotif from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in the central part of his piece. Such an encounter between high art and cakewalk creates a burlesque effect and desecrates the quasi-religious dimension of Wagner aesthetics.