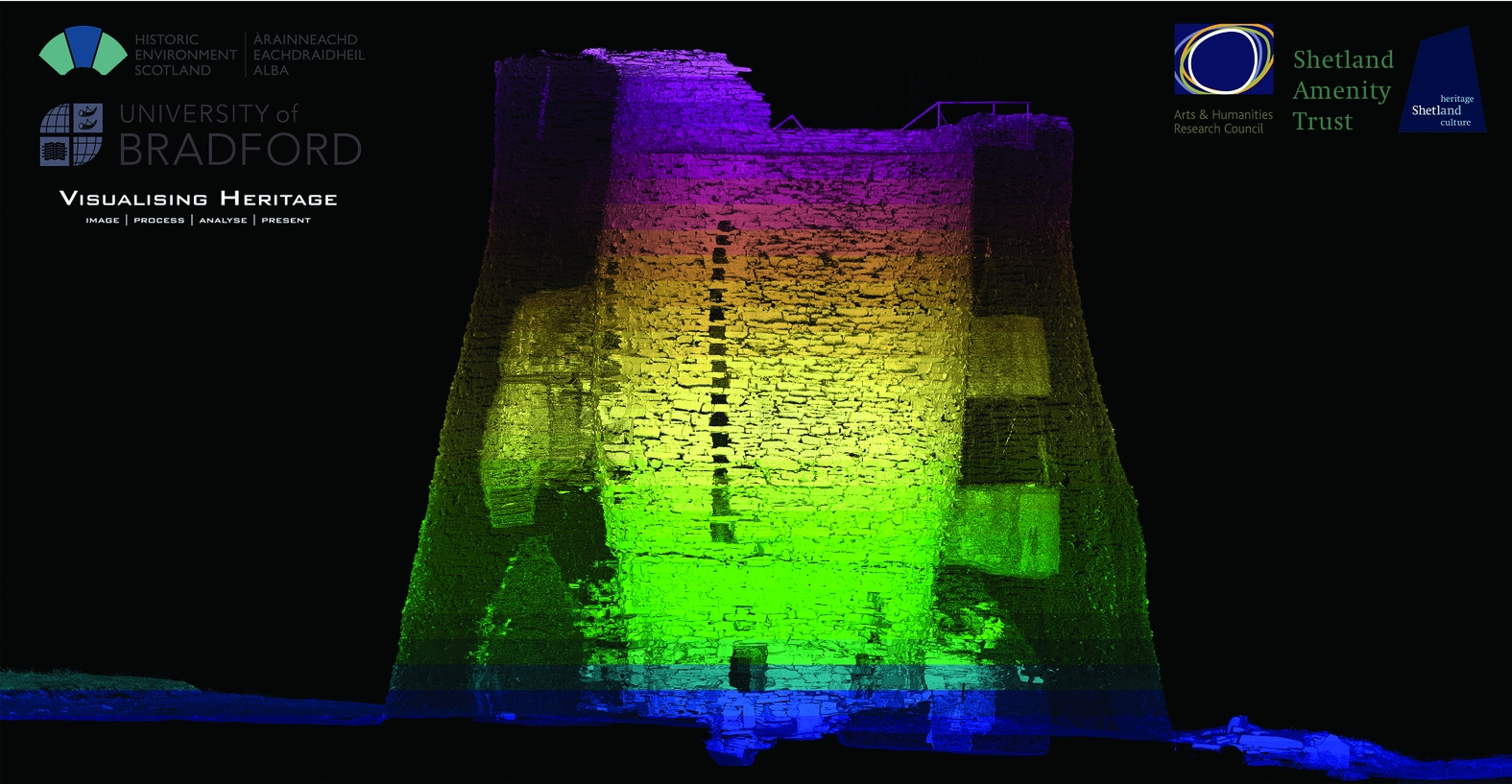

Frontispiece 1. Standing 13m high, the Broch of Mousa is exceptionally well preserved. The monumental drystone tower is located close to the shore of Mousa Island, overlooking the 1km-wide strait that separates the island from the east coast of Mainland, Shetland. Brochs such as this were constructed across Scotland between the fourth century BC and first century AD. Mousa Broch has been the subject of terrestrial laser scan surveys as part of the AHRC-funded doctoral project ‘Visualising the Crucible of Shetland's Broch Building’. This artificially coloured point cloud shows a cross-section of the broch, revealing details of its double-wall construction and various cells and galleries. Image: Li Sou and James Hepher. © Historic Environment Scotland and University of Bradford.

Frontispiece 2. The latest commission for the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, ‘The Invisible Enemy Should not Exist’ by Michael Rakowitz, was unveiled on 28 March 2018. Fashioned from Iraqi date-syrup tins, it represents the Lamassu that guarded the Nergal Gate at Nineveh from c. 700 BC until its destruction in 2015 by ISIS. In 2016, Trafalgar Square hosted a reconstruction of another monument destroyed by so-called Islamic State, Palmyra's Triumphal Arch. The latter has subsequently visited New York, Dubai, Florence and the Archaeology Museum in Arona, Italy. Photograph: Robert Witcher.

SAA in Washington, D.C.

When John F. Kennedy described Washington, D.C. as a city of Southern efficiency and Northern charm, it was presumably not intended as a compliment. Nonetheless, like all good quotes, it captures a wider truth—a capital city as the pivot of a vast and diverse nation, a symbolic and political, if not geographic, centre. In this sense, the choice of Washington, D.C. to host the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (SAA), 11–15 April 2018, was more than coincidence. With a still relatively new administration in the White House making policy changes with significant implications for the nation's cultural heritage, the gathering of more than 5000 archaeologists from the USA and beyond offered the opportunity to lobby politicians and policymakers on their home turf. Delegates were accordingly encouraged to contact their elected representatives, and the SAA Government Affairs Program pursued meetings on Capitol Hill to press the case for the protection and promotion of cultural heritage. The theme was reinforced through the SAA Presidential Sponsored Forum, entitled ‘Bears Ears, the Antiquities Act, and the Status of our National Monuments’, where the panel reflected on the effectiveness of the Antiquities Act of 1906 (now safeguarding over one million square kilometres of US territory) and the emerging threats to the protection it provides. In particular, the unprecedented proposal by the new administration to reduce significantly the size of one of the most recent additions to the list, the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah (as well as Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument), has led to concerns—and lawsuits—over political interference and the weakening of the protection that the Act provides for sites and landscapes across the USA.

As if to reinforce the political slant of this year's SAA, the meeting coincided with the Second International March for Science on 14 April, with thousands descending on Washington, D.C., and 200 other cities around the world, to advocate to politicians and lawmakers the importance of evidence-based policies and the use of science for the common good. Despite a packed conference schedule, some SAA delegates were able to head downtown to join the march and to represent archaeology alongside other disciplines from astronomy to zoology.

As in previous years, Antiquity attended the SAA meeting with an exhibit stand, providing the opportunity to meet some of our editorial advisory board members, contributors (several of whom feature in this issue), reviewers and readers, and to discuss and encourage ideas for future submissions. We were also pleased to support the SAA Student Paper Award. The winning paper, ‘Untapped potential—why weren't ceramic arrowheads invented? Theoretical morphology for understanding the human past’, was commended by the judges for its elegant research design, flawless execution and thoughtful conclusions. Our congratulations to joint authors Michelle Bebber and Mike Wilson from Kent State University!

Mount Vernon

Attending a conference such as the SAA involves academic sessions and networking, but also offers the opportunity to explore the host city and to reflect on its heritage. The National Mall, in the heart of Washington, D.C., is a powerful example of nation-building through the commemoration of the many individuals, groups and events that shape US history: the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial; the Second World War and Vietnam War Memorials; and two of the more recent additions to the Smithsonian Institution, the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of African-American History and Culture. Each contributes, in its own unique way, to the complex story of the USA. A short boat trip down the Potomac River, however, is an altogether less monumental place, but one that is freighted with no-less-powerful symbolism. Mount Vernon, the Virginia house and estate of George Washington, is something of a national shrine. Through the figure of Washington, the history of Mount Vernon is that of the nation itself. It is, to borrow a term from the historian Pierre Nora, a ‘lieu de mémoire’, a place invested with material memory and symbolic meaning. The home of America's founding father, revolutionary patriot and the original citizen-soldier-farmer, Mount Vernon embodies and legitimises the political values of the USA. And this symbolism is not accidental, for Washington himself consciously set out to encode these values into the house and estate. The plants and trees selected by Washington, for example, were almost exclusively American species, and his garden design eschewed European planting schemes for a more informal design. The great political symbolism of the site was underlined less than a fortnight after the SAA meeting, when the current White House incumbent descended on Mount Vernon with the French president, Emmanuel Macron. A focus of attention was the Bastille Key, given by Lafayette to Washington and now on display in the house.

Mount Vernon also holds a significant place in the history of conservation and heritage management in the USA. By the mid nineteenth century, the Washington family could no longer afford the upkeep of the house and estate, and the growing numbers of visitors were becoming a problem. With the powerful men of D.C. distracted by affairs of state, it fell to a group of women from Virginia, spearheaded by Ann Pamela Cunningham, to raise funds and buy the estate. Having acquired the site, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA)—who still own the site today—set to work preserving it for future generations. Cunningham's stirring words have guided conservation work at the site down to the present:

Ladies, the Home of Washington is in your charge. See to it that you keep it the Home of Washington! Let no irreverent hand change it; no vandal hands desecrate it with the fingers of—progress! Those who go to the Home in which he lived and died, wish to see in what he lived and died! Let one spot in this grand country of ours be saved from change! Upon you rests this duty. Footnote 1

With this philosophy in mind, successive generations of the MVLA have organised the careful restoration of the estate's extant buildings. They have also overseen the reconstruction of others, ranging from Washington's greenhouse, drawing on documentary evidence for the original 1792 structure, and, based on archaeological excavations, a dung repository or stercorary (the on-site interpretation panel announces this to be “the first known structure in the United States devoted to composting”!). Today, the visitor can also experience a blacksmith's workshop, a pioneer farm, a distillery and a gristmill amongst other attractions.

Mount Vernon was also the focus of pioneering conservation work to protect the visual setting of the site. During the 1950s, proposed development on the opposite shore of the Potomac threatened to blight the view that Washington had enjoyed from his verandah. It was through the efforts of local residents that the National Park Service and Congress reached an agreement to protect the view from developments by placing easements on private properties in the Piscataway Park. Although not perfect, the approach has effectively preserved the original setting of Mount Vernon, and the model has been adopted or advocated elsewhere in the USA.

Lives bound together

Washington's home has been a place of pilgrimage of more than two centuries, and visiting Mount Vernon today, it is difficult not to detect the hagiographic atmosphere. But there is much more to this place than its association with a single man. Not least, integral to every aspect of life at Mount Vernon was slavery. By the time of Washington's death, the estate owned over 300 enslaved people who laboured in the fields and house alike. Today, the existence of these enslaved people is increasingly acknowledged and actively promoted as a core part of the visitor experience. School parties and tourists can step inside the reconstructed barracks to experience where, and how, some of the enslaved people lived, visit the kitchens where they prepared meals for the Washington family, and see monuments, erected in 1929 and 1983, at the slave cemetery, just a few metres from Washington's own burial place.

Archaeology has been integral to reinserting slavery into the Mount Vernon narrative—and, by extension, into the national narrative as well. Excavations, past and ongoing, have discovered a wealth of material culture that attests to the burgeoning trade networks of the eighteenth-century estate, including imported ceramics from Britain and Germany, Chinese porcelain, glass vessels and tobacco pipes. That new global economy and its commodities was built substantially on slavery, yet it is the locally made ceramics, such as colonoware (Figure 1), that speak most directly to the presence of enslaved people at sites such as Mount Vernon. Handbuilt from local clays and never enumerated in the estate's extensive inventories, these vessels attest the presence of African (as well as Native American) groups, maintaining their familiar and distinct cultural forms. But they also point to the complexities of interaction between different communities and traditions; some colonoware vessels, for example, imitate or creolise European forms, and the general presence of these wares in kitchen middens at Mount Vernon may suggest informal exchange networks.

Figure 1. A colonoware bowl from the South Grove Midden excavations at Mount Vernon. The bowl (rim diameter 160mm) dates to Phase 1 (c. 1735–1758) and therefore probably relates to the household of Lawrence Washington, who passed the estate via his widow to his younger half-brother, George. Photograph © Mount Vernon Preservation.

Drawing on some of this archaeological evidence, the ‘Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington's Mount Vernon’ exhibition (Figure 2), on show from October 2016 to September 2019, presents a powerful insight into the links between the lives of Washington and his family and the enslaved people who laboured on the estate. Alongside archaeological artefacts are objects handed down to the descendants of Mount Vernon's enslaved people, as well as paintings, costumes and a range of documents. The latter include some of the many legal papers dealing with the purchase and sale of individual enslaved people, as well as letters between members of the Washington household and their staff, providing glimpses into daily life. These give us the names of some of the enslaved people—Caesar, Caroline, Christopher, Doll, Hercules, Ona, William—and occasionally clues to physical appearance and the briefest of biographical details: about running away, being caught and punished, and, for some, being freed. Visitors moving through the exhibition encounter these individuals, and as much of their personal stories as we have, in the form of evocative silhouettes and interactive screens. Running parallel to these biographies are thematic displays detailing work and life on the estate, including farming and gardening, clothing and personal ornaments, and, woven throughout, an overview of Washington's own evolving attitude to slavery. ‘Lives Bound Together’ is an eloquent and vital companion to the other displays at Mount Vernon, clearly speaking to contemporary concerns, not least the Black Lives Matter movement. Visitors to the site, whether school parties or presidents, should be sure to spend some time at this exhibition—as well as enjoying the splendid views of the Potomac preserved by the creative partnership of government agencies and local communities.

Figure 2. The ‘Lives Bound Together: Slavery at George Washington's Mount Vernon’ exhibition. Photograph © George Washington's Mount Vernon.

In this issue

Following his defeat of the British, Washington declined the opportunity to declare himself monarch, returning (briefly) to private life at his Virginia estate and earning the title of the ‘American Cincinnatus’. Fittingly, therefore, when he was laid to rest at Mount Vernon, first in the family vault and then in a bespoke tomb, these modest structures were less than regal. In contrast, two of the papers in this issue of Antiquity deal with more extravagant tomb sites. The first of these, by Hassett and Sağlamtimur, takes us to Mesopotamia and a large cist burial at the third-millennium BC site of Başur Höyük. Here, analysis of grave goods and human bone suggests a retainer burial, which the authors argue reflects a wider trend for human sacrifice during the unstable periods associated with the emergence of stratified—possibly royal—societies. The second paper, by Mizoguchi and Uchida, moves to China and the site of Yinxu. Drawing on the 1930s excavations of the royal Shang cemetery of Xibeigang (Hsi-Pei-Kang), the authors present a new chronological sequence—linking each tomb to a king named in the ancient sources—and explore how the location and orientation of the tombs physically and symbolically positioned both the deceased and the living in relation to the ancestors.

In addition, as ever, we have papers that range widely across time, space and topic, from the harvesting of wild cereals in the Upper Palaeolithic of the Yellow River Valley, China, through to a detailed analysis of the background to one of the key early twentieth-century articles on Stonehenge and the provenance of its bluestones. There is also enormous variation in scale, ranging from an examination of the impact of climate change on the thousands of archaeological sites across the Arctic, to the biography of a single Russian prisoner of war as evidenced through an aluminium canteen from Czersk, Poland. We also return to Çatalhöyük where a new suite of radiocarbon dates for the West Mound permits a wider re-evaluation of shifting settlement and population during the late seventh and early sixth millennia BC. We trust that all of our readers will find something of interest in this issue.

Antiquity prizes 2018

Finally, it is a pleasure to announce the winners of the 2018 prizes for the two best articles published last year in Antiquity, as voted for by our editorial advisory board members, directors and trustees. The Antiquity Prize goes to ‘Identifying ‘plantscapes’ at the Classic Maya village of Joya de Cerén, El Salvador’ by Alan Farahani, Katherine L. Chiou, Anna Harkey, Christine A. Hastorf, David L. Lentz and Payson Sheets.Footnote 2 Thanks to preservation by volcanic ash, the authors were able to examine in extraordinary detail the use of plants in gardens, fields and households at this Classic Maya site. The winner of the Ben Cullen Prize is ‘The Ypres Salient 1914–1918: historical aerial photography and the landscape of war’ by Birger Stichelbaut, Wouter Gheyle, Veerle Van Eetvelde, Marc Van Meirvenne, Timothy Saey, Nicolas Note, Hanne Van den Berghe and Jean Bourgeois.Footnote 3 Coinciding with the centenary commemorations of the Battle of Passchendaele, this paper demonstrates the insights that aerial photography can provide for our understanding of the archaeological landscape of the Western Front. Congratulations to all! You can read both of these articles, and all of the previous winners, for free at www.antiquity.ac.uk/open/prizes. While you are there, we invite you to explore the rest of the website and to discover a variety of other content from the world of Antiquity.