I Introduction

The United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) had been mandated by the UN Security Council to “support the efforts of the Government of Afghanistan in fulfilling its commitments to improve governance and the rule of law.”Footnote 1 In hindsight, after the irregular seizure of power by the Taliban government on August 15, 2021, this reads as being, misguided and naive. After all, the twenty-year-long, UN-led rule-of-law process in Afghanistan, including the adoption of a liberal constitution with intense UN (and US) involvement,Footnote 2 seems to have been annihilated.

UNAMA is only one example of the widespread rule-of-law-related activities by a range of international organizations at different places on the globe. This chapter spotlights their recommendations and prescriptions on constitution-making and reform – which involve the rule of law as a constitutional principle.Footnote 3 The explanation for focusing on constitution-making and reform is that the rule of law seems to be better protected when a given polity possesses a constitution. The UN Secretary-General’s 2008 Guidance Note on the Rule of Law posits as a “framework for strengthening the rule of law” a “Constitution or equivalent, which, as the highest law of the land,” must also possess certain ingredients, ranging from the incorporation of international human rights guarantees to upholding an independent judiciary.Footnote 4

The constitution-shaping activity of international organizations involves other constitutional principles besides the rule of law, notably human rights and democracy.Footnote 5 Depending on how it is conceptualized, the rule of law encompasses or complements these ideas.Footnote 6 Importantly, UN member states have embraced the rule of law as a lead concept for both domestic and international law:Footnote 7 the key General Assembly resolution expressly stipulates that “the rule of law applies to all states equally and to international organizations, including the United Nations and its principal organs.”Footnote 8 This statement indicates that the rule of law has a transnational or multilevel quality.Footnote 9

The chapter proceeds as follows: Part II gives some examples of how, since 1989, international organizations have sought to shape state constitutions and thereby the domestic rule of law. Part III briefly shows that, for the most part, these activities have not led to better operation of the rule of law on the ground. Next, in Part IV, the main critiques against constitutional assistance and advice by international organizations are listed. My response is that, in order to become more legitimate (which might then also improve effectiveness) constitution-shaping by international organizations needs to absorb postcolonial concerns and must be complemented by a much deeper social agenda with a global ambition (Part V). Thus revamped, international organizations’ constitution-shaping role could be reinvigorated so as to sustain the rule of law on the domestic level (Part VI).

II Constitution-Shaping in Various Guises

1 Membership Conditions

Since 1989, organizations such as the European Union (EU), the Council of Europe (CoE), and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) have stimulated serious constitutional reforms in those Eastern and Central European states that sought to accede. As a condition for membership, deep rule-of-law-related reforms had to be undertaken.

The most influential organization has probably been the EU. Twelve Central and Eastern European candidate states acceded to the EU in two main waves, in 2004 and 2007.Footnote 10 When the first Central Eastern enlargement was under discussion, the European Community, as the organization was then called (under the broader ‘roof’ of the European Union), did not yet possess substantive accession criteria in its primary law. Rather, the accession criteria were spelled out in the Presidency Conclusions issued at the European Council’s Copenhagen meeting in 1993 in which it was stated:

Membership requires that the candidate country has achieved stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities, the existence of a functioning market economy as well as the capacity to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union. Membership presupposes the candidate’s ability to take on the obligations of membership including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union.Footnote 11

Later, these so-called Copenhagen criteria for accession were written into the 2007 Lisbon version of the Treaty on European Union in Article 49, read in conjunction with the clause on the Union’s “values” in Article 2. These “values” include the rule of law.Footnote 12 As a result, accession of the new Central and Eastern European states to the EU implied transformations that affected “the very structure of the constitution” of those states.Footnote 13

Similarly, the CoE requested rule-of-law reforms. The accession standards are laid down in Article 3 of the organization’s founding treaty (the Statute of the CoE) and in secondary law. Article 3 requires acceptance of “the principles of the rule of law.” In accession practice, this provision has been interpreted as requiring ratification of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the establishment of a pluralist parliamentary democracy.Footnote 14 Membership is strictly conditioned upon having a liberal and democratic constitution that endorses the trinity of rule of law, human rights, and democracy.Footnote 15

Admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO) also had repercussions for the rule of law. The requirements for WTO membership are laid down in so-called accession protocols, which differ from one candidate state to another. A famous case was China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. In its accession protocol, China notably committed itself to transparency and judicial review.Footnote 16 Transparency and judicial review are key components of the rule of law. These principles must now be observed by China in trade and economic policy, because the state would otherwise not be fulfilling its treaty obligations.

These examples illustrate how the prospects of accession to various international and regional organizations have functioned as incentives for domestic constitutional reforms, including the improvement of rule-of-law-related institutions.

2 Conditionalities, Indicators, Benchmarking, Advice

Further and subsequent to preaccession incentives, the activity of international organizations has the potential to directly or indirectly shape the constitutions of states, which in turn has repercussions on the national rule of law. Rule-of-law promotion by international organizations that calls for constitutional reform often overlaps with other activity that does not directly address or imply specifically constitutional law. A famous example is the Venice Commission’s Rule of Law Checklist of 2016.Footnote 17 Also the UN Secretary-General has defined the rule of law in the context of transitional justice.Footnote 18

This chapter leaves aside those rule-of-law activities by international organizations that pertain to specific fields such as fighting impunity. Also, it leaves out the work of universal human rights bodies and regional human courts, although, as part of their human rights monitoring, they occasionally recommend or request not only individual measures toward specific victims or legislative reforms but also constitutional reforms to remedy human rights violations. A recent example is the response to the ongoing rule-of-law crisis in Hungary and Poland. Here, European courts have derived the states’ obligations to restore an independent judiciary from human rights obligations.Footnote 19 Another example of explicit and broad rule-of-law requests by a human rights body is the work of the Inter-American Commission concerning corruption – corruption (the rule of money) being the antithesis of the rule of law.Footnote 20

International financial institutions (IFIs), especially, have exercised pressure to reform state constitutions. Their activity (of both benchmarkingFootnote 21 and outright conditionalities) has included a focus on explicit requests for rule-of-law-related reforms, which in turn imply constitutional reform. For example, the worldwide governance indicators created by the World Bank and the Brookings Institution have always invoked the rule of law. And the World Bank country policy and institutional assessments (CPIA), which since 2005 have been made public, rate the recipient countries according to various criteria such as “property rights and rule-based governance” and “transparency, accountability, and corruption in the public sector.”Footnote 22

The next most relevant constitutional dimension affected by IFIs’ activities concerns the welfare and social provisions of state constitutions. World Bank and IMF policies, programs, and rules of the game, notably the conditionalities, may affect the recipient states’ bureaucracy and influence public spending (e.g., on state education).Footnote 23 As part of adjustment programs set up by IFIs, states have enacted legal reforms that have negatively affected the enjoyment of constitutionally (and internationally) guaranteed human rights, such as entitlements to pensions protected as property, the right to social security, the right to health, and the right to education. These rights form part of a “thick” and “social” vision of the rule of law.Footnote 24

Another “defender of the rule of law” (to use the word of its former Director and Secretary Thomas Markert) is the Venice Commission.Footnote 25 This is a body operating within the framework of the CoE.Footnote 26 Since its creation in 1990, the Venice Commission has been heavily involved in constitution-making and constitutional reform, always upon a request from a member state, a body of the CoE such as the Committee of Ministers or the Parliamentary Assembly, or from an international organization such as the EU. The Venice Commission has issued opinions that concern the drafting of entire constitutions or significant parts of them, has provided assistance for constitutional reforms, and has made pronouncements on legislative projects that flesh out constitutional provisions in numerous cases. The Commission notably gives regular advice on the organization of the judiciary and on electoral law. Although the latter group of opinions formally rank as provisions of ordinary statutory law, they are eminently important for the practical functioning of the rule of law in the states concerned.Footnote 27

Outside Europe, regional organizations have been working to support the establishment, consolidation, and protection of democratic systems of government, and concomitantly the rule of law. The Organization of American States adopted the Inter-American Democratic Charter on the very day of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Article 2 of the Charter states that “[t]he effective exercise of representative democracy is the basis for the rule of law and of the constitutional regimes of the member states of the Organization of American States.”Footnote 28

In 2007, the African Union adopted the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.Footnote 29 Under this instrument, which entered into force in 2012, the Peace and Security Council (PSC) of the African Union can suspend governments that have come to power through an unconstitutional change in government. Such suspensions have most recently been put in place against Mali, Guinea, Sudan, and Burkina Faso after military coups in those states.Footnote 30

Given that many other rule-of-law-related activities of international organizations also, to a lesser or greater extent, involve state constitutions, the examples given in this section are incomplete. They must suffice to illustrate the claim that international and regional organizations have a track record of attempting to improve the “domestic” rule of law by shaping the constitutions of their member states. The intensity of their engagement has varied greatly, however, across the different regions of the world.

3 Constitution-Shaping by the United Nations

A special case is UN assistance in constitution-making and constitutional reform processes in the Global South (Africa, Latin America, the Near East, and Asia).Footnote 31 Since 1989, albeit with different degrees of intensity, the United Nations has been involved in constitutional processes in at least nine states, ranging from Yemen in 1991Footnote 32 to the Central African Republic in 2016.Footnote 33 The list includes Cambodia (1993),Footnote 34 Guinea-Bissau (substantial constitutional revision in 1996),Footnote 35 Afghanistan (2004),Footnote 36 Libya (2011),Footnote 37 and Côte d’Ivoire (2016).Footnote 38 The UN has also participated in the creation of two new states and their constitutions (East Timor (2002) and South Sudan (2011)).

a Constitution-Making as Peacemaking

All these constitution-shaping activities were set in the context of peace processes. The United Nations’ involvement was based on the understanding that peacemaking requires (inter alia) the creation of a state constitution which in turn implements the rule of law.Footnote 39 In 1992, the UN Secretary-General had already asserted that there was “an obvious connection between democratic practices – such as the rule of law and transparency in decision-making – and the achievement of true peace and security in any new and stable political order.” Once such a link is presumed, the United Nations are not only authorized by its membership but even “have an obligation” to provide “technical assistance” and give “support for the transformation of deficient national structures and capabilities, and for the strengthening of new democratic institutions.”Footnote 40

Next, in the 1996 Agenda for Democratization, Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali stressed a new, constitution-shaping role for peace missions: “The peace-keeping mandates entrusted to the United Nations now often include both the restoration of democracy and the protection of human rights. United Nations departments, agencies and programmes have been called upon to help States draft constitutions … .”Footnote 41 In 2001, the Secretary-General ascribed even a conflict-preventing role to the rule of law: “An essential aspect of conflict prevention is the strengthening of the rule of law, and within that the protection of women’s human rights achieved through a focus on gender equality in constitutional, legislative, judicial and electoral reform.”Footnote 42

In his annual report for 2005, under the heading “Achieving peace and security,” the UN Secretary-General made a point of mentioning rule-of-law promotion as a task of the peace missions:

The United Nations worked tirelessly around the globe throughout the year to prevent and resolve conflicts and to consolidate peace. … Peacekeepers deployed to conflict zones in record numbers and in complex multidimensional operations, working … to help war-torn countries, write constitutions, hold elections and strengthen human rights and the rule of law. United Nations agencies, funds and programmes tailored their assistance to the special needs of post-conflict societies.Footnote 43

In his 2006 progress report on conflict prevention, under the heading “Strengthening norms and institutions for peace,” the UN Secretary-General mentioned that “the United Nations and its partners offer a variety of important services, at the request of Member States. These include electoral assistance, constitutional assistance, human rights capacity-building,” and more. These important services are intended to help individual governments “ find their own path to democracy.”Footnote 44

In all instances, the United Nations had established peace missions on the ground, sometimes in collaboration with regional organizations. The transitional processes, including constitution-making, frequently involved those missions. In sum, the UN has consistently depicted its rule-of-law activities as a contribution to peace (broadly conceived) and as being instrumental not only in managing and terminating armed conflict but even preventing such conflict.

b UN Guidance on Constitutional Process and Substance

It took the United Nations several years of action on the ground to develop guidance notes for the processes of constitution-making and for the substance of the new or reformed constitutions. Building on the 2008 guidance note on the UN approach to rule of law assistance,Footnote 45 a specific guidance note on constitution-making processes was issued by the UN Secretary-General in 2009. In its own words:

The note sets out a policy framework for UN assistance to constitution-making processes derived from lessons learned from constitution-making experiences and from UN engagement in these processes. It is informed by the Guidance Note of the Secretary-General on United Nations Approach to Rule of Law Assistance. It outlines the components of a constitution-making process and identifies the expertise the UN will require to provide effective assistance.Footnote 46

As far as the constitutional processes are concerned, the 2009 note lists the following guiding principles:

1. Seize the opportunity for peacebuilding

2. Encourage compliance with international norms and standards

3. Ensure national ownership

4. Support inclusivity, participation and transparency

5. Mobilize and coordinate a wide range of expertise

6. Promote adequate follow-up.Footnote 47

In contrast to these procedural steps, the 2009 guidance note does not prescribe particular substance for the (new or amended) state constitution. The premium placed on “national ownership” gives the target state leeway in that regard. But this leeway is not boundless, because not only the constitutional process but also its substance need to satisfy “compliance with international norms and standards.”Footnote 48 Moreover, the earlier 2008 guidance note on the UN approach to the rule of law even refers to specific constitutional content: It quite precisely describes the principles and ingredients that a state constitution needs to display in order to conform to the rule-of-law ideal as defined by the UN. They range from the incorporation of international human rights treaties, to nondiscrimination and gender equality, to institutions based on and limited by law, to an impartial judiciary.Footnote 49

c Involvement of the Security Council

The Security Council, in particular, has placed normative demands on states. Security Council resolutions, sometimes adopted under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, have reiterated the principles of constitution-making, both with respect to process and constitutional substance. This activity overlaps with the Security Council’s rule-of-law agenda.Footnote 50 Importantly, China and Russia – to mention but these two powers with a right of veto – have regularly voted in favor of these resolutions. This practice shows that something like a transnational rule-of-law consensus is still alive – at least when the interests of the two anti-liberal powers, China and Russia, are not directly affected.

With regard to constitutional process, the Security Council has restated principles of “national ownership.”Footnote 51 Frequently, the Security Council has urged free and fair elections as part of a transition and reconciliation process (such as for Cambodia in 1992,Footnote 52 East Timor in 2001,Footnote 53 Afghanistan in 2005,Footnote 54 Libya (most recently in 2020),Footnote 55 Yemen,Footnote 56 South Sudan,Footnote 57 and the Central African Republic (CAR)).Footnote 58

Many more Security Council resolutions imply the need to organize elections or a referendum, such as in Somalia in 2012, where the UN mission was tasked with giving strategic policy advice on peace-building and state-building, including a “referendum on the constitution; and preparations for elections.”Footnote 59 This is not a phenomenon of the past but is ongoing. The Security Council asked the Integration Peacebuilding Office in Guinea-Bissau and the special representative to “support, through good offices,” democratic elections in Guinea-Bissau in 2019.Footnote 60 In the same year, the Security Council asked the UN Secretary-General to establish in Haiti a UN office whose key tasks was to include assisting the government to “plan and execute free, fair, and transparent elections.”Footnote 61

The Security Council has also – and this is related to the democratic principle – encouraged “inclusive” and participatory processes of constitution-making and constitutional reform (for South Sudan in 2011,Footnote 62 Libya in 2011,Footnote 63 Yemen in 2012,Footnote 64 and Guinea-Bissau in 2019Footnote 65). It also asked for transparent procedure (for example, in YemenFootnote 66). Finally, the Security Council has frequently and explicitly voiced its expectation that women participate in the constitutional process, such as in South Sudan 2011,Footnote 67 the Central African Republic in 2014,Footnote 68 Guinea-Bissau in 2019,Footnote 69 Haiti in 2019,Footnote 70 and Libya in 2020.Footnote 71

Another set of Security Council propositions concerns the substance of the constitution. The normative advice covers all three limbs of constitutionalism’s trinity. First of all, the Security Council inevitably required the new constitution to be built on the rule of law, as it did for Afghanistan in 2011,Footnote 72 Somalia in 2013,Footnote 73 and Mali in 2013.Footnote 74 With regard to the constitution of Guinea-Bissau, the Security Council asked for the separation of powers and access to the judiciary (2019).Footnote 75 Second, the Security Council has often suggested that the new constitution must be democratic, such as in East Timor in 2001,Footnote 76 Afghanistan in 2005,Footnote 77 Libya in 2011,Footnote 78 South Sudan in 2011,Footnote 79 and Mali in 2013.Footnote 80 Third, human rights protection has been explicitly required, as for Afghanistan.Footnote 81 Finally, the Security Council recommended a federal system for Somalia in 2013.Footnote 82

The Security Council’s intense engagement with the rule of law (broadly conceived) is tempered by the fact that of the resolutions mentioned only four were adopted under Chapter VII.Footnote 83 Of those, to the best of my knowledge, only Resolution 2149 (2014), on technical assistance to elections in the Central African Republic, employs mandatory language.Footnote 84

The other resolutions, even if the resolutions as such were based on Chapter VII, couch the principles on process and substance of constitution-making in soft language, often placed in the resolutions’ preambles. Most resolutions were based on Chapter VI. These, like the majority of the Chapter VII resolutions, merely “stress” the importance of constitutional principles, and they “encourage”, “support”, and “assist” the states concerned, but do not “request” or “impose” anything.

III Have International Constitution-Shaping Efforts Led to Domestic Rule-of-Law Improvements?

Part II has shown that the rule of law has been espoused and disseminated through the constitution-shaping activities of international organizations in all regions of the world. The rule of law has thereby become part and parcel of the web of international norms and standards that forms a benchmark for state constitutions. It has become a global principle of constitutionalism, or a principle of transnational ordering – at least on paper. However, the real effects of international organizations’ constitution-shaping so that the rule of law benefits people on the ground are very difficult to measure.Footnote 85 The situation is further obscured by the continued tendency of recipient states to point to international organizations as convenient scapegoats in order to hide their own policy choices. The question of effects and limits can therefore not be answered in a definitive way. We can only take snapshots.

1 Universal Organizations

With regard to international financial institutions, their impact on recipient states’ tax revenues, public sector wages, and the like has been corroborated by recent studies.Footnote 86 This impact partly concerns the states’ constitutions and the domestic rule of law. However, it has mostly been evaluated as being negative for the concerned populations.Footnote 87

The effects of accession to the WTO on the Chinese constitution and rule of law have been variously assessed. Eight years after accession, Esther Lam found that the WTO requirements formed an important model for further changes in non-WTO-related areas “such as uniformity of laws and legal administration, non-discrimination, transparency, and impartial mechanisms for challenging government decisions and actions.”Footnote 88 Lam also claimed that “[a]lthough the enforcement of laws remains weak, legal rules are assuming an unprecedented level of prescriptive power in post-WTO accession China.”Footnote 89 According to Lam, the result was, inter alia, “legal guarantees to individual freedom of actions and the right to trade, and it [the enhanced role of law] restricts political power from arbitrarily encroaching onto spheres where law does not prescribe it to do so.”Footnote 90 In contrast, more recent studies have downplayed or denied the impact of WTO membership on China’s rule of law.Footnote 91

2 European Organizations

The constitution-shaping by the two European regional organizations – the EU and the CoE – has only in part produced deep and lasting effects. Political scientists found that the EU’s political accession conditionalities had a “tremendous impact” on what they called the “Europeanization” of Central and Eastern Europe.Footnote 92 It has also been said that “[h]uman rights, liberal democracy, and the rule of law are the fundamental rules of legitimate statehood in the European Union.”Footnote 93

However, the EU’s preaccession “pull” toward the rule of law is by no means guaranteed. Since Croatia’s accession to the EU in 2013, other Eastern European states (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia) have not moved closer to accession. Montenegro and Serbia have been conducting accession talks since 2012 and 2014, respectively, but the prospect of accession does not seem to have initiated a further dynamic of constitutional reform in those states.

With regard to the actual constitutional reforms triggered by accession to the EU, Anneli Albi found that the constitutional amendments in Central and Eastern European countries “remained relatively minimal” – often contrary to initial enthusiast rhetoric.Footnote 94 From the outset, “international socialization” through the EU (and the CoE) did not work in those states that had been clearly antiliberal, such as Belarus, Ukraine, Serbia, or Russia.Footnote 95 For those states that had already been on the path to liberalism before the accession to the CoE (Estonia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovenia), it first looked as if the liberal constitutional principles required by both organizations for membership would work well. But thirty years later, some of these states have turned away from the international standards and are becoming illiberal democracies, such as Hungary and Poland.

Current events in the EU seem to confirm that once a state has been admitted to the international organization, there is no longer any leverage to press for reforms, as the carrot of membership that was the incentive for reform has gone. This then leads to a loss of effectiveness of any further constitutional intervention. Whether new tools such as the EU’s so-called rule-of-law mechanism can bring illiberal member states back in line and up to constitutionalist standards is unknown for the time being.Footnote 96

For the CoE, it is obvious that the actual application and implementation of these imperative constitutional principles on the ground have been only weakly monitored. Russia, which was excluded from the Council in March 2022, is an example – the organization had arguably not properly responded to Russia’s continual disregard of the rule of law until it turned into extreme violation when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022.

All this suggests that the European organizations’ impact on strengthening the rule of law in accession candidates and member states has been uneven.

3 UN Impact on Constitutions in the Global South

The lack of effectiveness of rule-of-law building through constitutional assistance is especially palpable in the Global South. Once the constitution is made, with international assistance and following international standards, it needs to be put to work by domestic actors. But this generally does not function well. The lofty constitutional principles adopted under the influence of the United Nations or other foreign actors have frequently not been translated into concrete rules that are followed by state officials.

Take the constitutions of Cambodia (1993, as amended up to 2008), South Sudan (2011), and the Central African Republic (2016), to name but three constitutions that were recently adopted with UN and other international actors’ assistance. They all contain catalogues of fundamental rights that on the whole faithfully mirror international human rights standards and are complemented by features specific to each region.Footnote 97 However, constitutional rights are hardly applied on the ground due to a lack of infrastructure, impunity of violators, dictatorship (as in Cambodia), and armed conflict (as in the Central African Republic).Footnote 98 In extreme cases, constitutional rights exist only on paper. In all cases, a gap of greater or lesser glaringness persists between the constitutional document and its effects on the political, legal, and administrative practice of public institutions.Footnote 99

4 Observations

In conclusion, both in Europe and in the Global South, the external constitutional assistance lent by international organizations has produced only moderate positive effects – if any at all – for the functioning of the rule of law.

Already in 2011, a consultative process on rule-of-law assistance organised by the UN found that rule-of-law assistance was “too often executed in an ad hoc manner, designed without proper consultations with national stakeholders, and absent exacting standards of evaluation.” It inquired how “rule of law assistance can be better channelled to deliver results.”Footnote 100

Probably, the advising and accompanying organizations would need to pay much more attention to the matter of practical application and transposition of constitutional and rule-of-law principles into (ordinary) domestic law. It has been asserted that in recent instances of UN constitutional assistance, the question of implementation was barely touched on at the stage of constitutional negotiations.Footnote 101

However, implementation depends first of all on the states themselves. A chief reason for the constitutions having little impact is probably the fragility of the institutions in the states concerned. Many factors contributing to this fragility are (and properly so) beyond the reach of the international organizations.

Also, it is unlikely (although – as a counterfactual – not verifiable by empirical investigation) that the constitutions would work better in practice had they been adopted without any external assistance. It must remain a matter of speculation whether purely home-grown constitutions in those countries would be (or have been) more socially acceptable because of a stronger sense of ownership and because of a better fit to local norms. Social acceptance normally leads to better compliance. But the price to pay might be deficiencies in substance and an even larger distance from the constitutional ideal of the rule of law.

IV Critiques

“[O]n the whole,” external influence (including, but not limited to, that of international organizations) on constitution-making and -shaping processes is said to have been “enormously useful in the development of constitutional law in countless countries in recent decades.”Footnote 102 At the same time, the sentiment lingers that international organizations’ various techniques of cajoling, persuading, and motivating states to adopt constitutions that embody the rule of law constitute an unlawful intervention into the domestic affairs of the receiving states, a risk of infringement of state sovereignty and national self-determination, or simply unfairness and normative inappropriateness due inter alia to selectivity and hypocrisy. Accordingly, constitution-shaping and other forms of rule-of-law promotion by various international organizations have been denounced as an illegitimate exercise;Footnote 103 they have been condemned as “evangelization,”Footnote 104 “meddling,”Footnote 105 and legal imperialism.Footnote 106

In the context of the reception of European human rights standards disseminated by the EU and the CoE in Central and Eastern European states, Romanian scholar Alexandra Iancu, already in 2014, diagnosed a prevailing “double standard sentiment” that held a “backlash potential.”Footnote 107 This potential seems now to have become fully realized.Footnote 108 All international organizations, and especially IFIs, have come under heavy fire for pursuing neoliberal policies that manifest the preferences and interests of the states of the North at the expense of the Global South.Footnote 109

Vijayashri Sripati criticizes especially the United Nations’ constitutional assistance from the perspective of Third World Approaches to International Law (TWAIL).Footnote 110 She perceives a historical continuity in constitutional assistance from colonialism to the post-1945 involvement of the UN Trusteeship Council in nonsovereign territories and to the revival of constitutional assistance after 1989, offered to formally sovereign states.Footnote 111 Sripati’s key claim is that a kind of internationalization of state constitutions has been brought about through the combined interventions of the United Nations and international financial institutions (World Bank and International Monetary Fund) against the background of poverty and high indebtedness of the receiving states. According to Sripati, the underlying political and economic agenda is to create a constitutional environment that is favorable to the West (and to investors). Ultimately, Sripati claims, “powerful Western states create within developing states constitutional regimes that have the effect of throwing open the latter’s resources for the transnational capitalist class (TCC), that is, the banks, investors, corporations, and geopolitical/imperialist strategists.”Footnote 112 The reproach is that the international organizations themselves are captured by global capitalist interests. Moreover, this strategy of “creating within developing states a constitutional environment that is not inimical to the West, but officially explaining it as being intended to modernize the former – is reminiscent of the imperial civilizing mission.”Footnote 113 The receiving states are, once again, “entrapped in an imperial relationship, although this time they are ostensibly sovereign.”Footnote 114 The constitutional assistance extended by the United Nations, in tandem with the Bretton Woods institutions, is thus a form of “legal imperialism.”Footnote 115

Another source of illegitimacy concerning the constitutional interventions of international organizations might be the cultural inaptness and lack of local roots of the rule of law and other constitutional principles. The shallowness of the normative consensus on constitutional substance might also explain the deficient implementation of constitutional law in receiving countries. With regard to human rights, it has been argued that domestic and external actors have often agreed only on a narrow set of rights, leaving out other matters. Inaptness might also arise in relation to further constitutional features such as the separation of powers or the independence of the judiciary.

Alexandra Iancu, who examined the Europeanization of human rights protection in the Eastern and Central European countries in the postaccession period, painted a gloomy picture of “limited substantial transformations,”Footnote 116 “shallow Europeanization,”Footnote 117 and “post-accession decline … reversing or distorting the very essence of newly created institutions.”Footnote 118 She pointed out that the Europeanization process “failed in producing the cultural background of the law providing the proper meaning of new provisions.”Footnote 119 She also deplored that European norms had been imposed “with no reference to value-systems, traditions, or practices” in the region of Central and Eastern Europe.Footnote 120 This situation, she wrote, is “conducive to a polarization of the national legal culture and a legalistic Babel in which each side selectively quotes European standards or the ECHR jurisprudence.”Footnote 121

Another set of critiques against constitution-shaping by international organizations points out that it has neglected the necessities of economic development in the target countries. It highlights that the institutions which must implement the rule of law (a functioning administration, courts, democratic electoral system, and so on) expend resources that should first be used for the economic development of a state. A related point is that the actual enjoyment of the supposed benefits of the rule of law (ranging from the exercise of political and civil rights to informed participation in elections) presupposes a certain level of economic development and material security for the population. According to the critique, these material factors are neglected or even worsened by the international organizations.

V Responses

The critical assessment of international organizations’ constitution-shaping is timely and necessary. However, it needs to be nuanced. An accusation that all constitution-shaping exercises serve only the global capitalist class yet again presents a master narrative explaining the world. Ultimately, it is as simplistic as the story of the selfless and humanitarian promotion of the rule of law for the benefit of the local population that it seeks to dispel.

1 Respecting State Sovereignty

Constitutional assistance by international organizations would violate the principle of non-intervention if the organizations intruded upon the domaine réservé of the target state and, additionally, the means of interference amounted to “coercion.” However, the rule of law no longer pertains to the domaine réservé. Rather, like human rights and democracy, it has become a familiar topos in international legal discourse – not the least through the constitutional assistance of international organizations. The approval and continuity of such practices has created a loop by which these issues (respect for the rule of law, human rights, and democratic processes) have been lifted out of the domaine réservé of states – they have been transnationalized.Footnote 122 Although somewhat circular, this process now means that the constitutional assistance afforded by international organizations can no longer be categorically dismissed as unlawful intervention. Rather, the practice has created the space for examining the extent to which the objectives of constitutional assistance justify the means employed by the organizations, and whether the means–ends relationship is proportionate.

The second prong of a prohibited intervention (coercion) is not an all-or-nothing concept. Only when interference in state affairs reaches a certain intensity or “magnitude”Footnote 123 will it leave the realm of lawful pressure and cross the threshold of “coercion.”Footnote 124 This threshold is defined by relying on reasonablenessFootnote 125 or through balancing: the interference amounts to an unlawful intervention when either the means or the ends are per se unlawful, or when means and ends in combination become unlawful, notably because the means–ends relationship is not appropriate (i.e., disproportionate).Footnote 126 Factors to take into account are the depth of the interference with interests of the target state, the breadth (effects on third states), the duration of the measure, and the objectives of the interference.Footnote 127 It is often stated that the aim of bringing about a regime change is “the most coercive form of political interference.”Footnote 128 The adoption of a new constitution, especially when combined with elections, can be seen as a regime change, and therefore could be accused of having crossed the red line to become unjustified intervention.

However, in formal terms, constitutional assistance by international organizations is generally not coercively imposed. Constitution-making assistance has been offered only on request. For example, the 2009 UN guidance note on constitution-making emphasizes that UN assistance will be offered only “when requested by national authorities.” In line with this, UN bodies should “recognize constitution-making as a sovereign national process, which, to be legitimate and successful, must be nationally owned and led.”Footnote 129

Coercion may nevertheless be present informally, due to economic dependency. The formal voluntariness of consenting to constitutional assistance, and especially to austerity programs with constitutional repercussions, might only be a sham. With regard to UN assistance, Vijayashri Sripati has argued that receiving states consent only “technically speaking” to the adoption of a new constitution. In reality, they are faced with no choice because they are “groaning under mountains of debt.”Footnote 130 Their consent is therefore, according to Sripati, “utterly compromised.”Footnote 131

In a similar way, the acceptance of pre- or postaccession conditions for membership of a given organization, and the signing of memorandums with international financial institutions might be made de facto inevitable by economic and political circumstances. Formally, states apply to the World Bank for project financing, and they ask the international monetary fund for a credit. States wish to join the EU – they could also stay out. However, strong factual constraints push the states to apply “voluntarily.”

Do these constraints lead to “imposition” by the international organizations? I submit that this is not the case as long as the pressure does not amount to coercion or military threat. Relevant legal thresholds have been developed in practice and in scholarship regarding “coercion,” not only for the definition of “intervention,”Footnote 132 but also in the context of the conclusion of treaties (Articles 51 and 52 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties)Footnote 133 and the use of force prohibited by Article 2(4) of the UN Charter. Although the thresholds differ in detail, they all convey the legal message that constraints resulting from an unfavorable economic and political position, weak bargaining power, and even a situation perceived by a state as leaving it with no choice do not undermine the state’s “free” decision. These thresholds and delimitations can also be applied to situations where constitutional assistance is invited. It is “free” and “voluntary” in the eyes of international law as long as the inviting state has not been pressured by military threats.

However, this answer of international law is formalistic and reflects the interests of the most powerful states of the North. Therefore, the assessment of lawfulness does not obviate the need to examine the broader issues of legitimacy.

2 Respecting Local Rule-of-Law Cultures

The critiques mentioned above suggest that when constitutional assistance is provided by international organizations care needs to be taken to avoid legal imperialism, double standards, capitalist capture, and cultural imposition. At this point, we need to distinguish between radical repudiation of the rule of law as such and the less profound problem of a lack of culture-specific adaptations. While a radical repudiation of the rule of law is nowhere to be found, assistance that is applied schematically and without adequate consideration of the need for local adaptations in the rule of law seem to be real issues.

As far as UN activity is concerned, after some years of experimenting with transitional justice, the UN Secretary-General admitted: “Unfortunately, the international community has not always provided rule of law assistance that is appropriate to the country context. Too often, the emphasis has been on foreign experts, foreign models and foreign-conceived solutions … .”Footnote 134 He continued that “we have learned” that the transitional justice processes need to be based on a thorough analysis of the local situation, based preferably on “expertise resident in the country,” and that the processes must be based on “active and meaningful participation of national stakeholders … while leaving process leadership and decision-making to the national stakeholders.”Footnote 135 “Pre-packaged solutions are ill-advised. Instead, experiences from other places should simply be used as a starting point for local debates and decisions.”Footnote 136 Although these “lessons learned” pertained to transitional justice processes, they would seem equally to apply mutatis mutandis to constitutional assistance.

Because law is a product of culture and society, difficulties arising from deep differences in legal culture (and culture more generally) are serious. The identification of the problem, the “lesson” drawn, is only the first analytical step, and in no way guarantees that a remedy is at all possible. We need to acknowledge that the rule of law is so abstract that it cannot “deliver” anything in and of itself.Footnote 137 The tension between the vagueness of the rule of law and the fact that it is contingent on concrete and context-dependent, bottom-up action on the ground remains irresolvable.

The next big problem is the rule of law’s Eurocentric and colonial baggage. In order to overcome this, the international organizations need to take up the ideas flowing from non-European constitutionalist thought.Footnote 138 For example, the Latin American concept of a “social rule of law” could be inspiring.Footnote 139

3 A More “Social” Rule of Law

The aforementioned idea of a “social rule of law” underlines the spreading insight that the neoliberal constitutional frame that has been pursued by a number of international organizations is not enough. A key problem in constitution-shaping has been the neglect of the social dimension of constitutionalism, in line with an exclusively formal conception of the rule of law. However, this neoliberal tilt – especially when it comes to IFIs – is not inevitable and not historically entrenched.Footnote 140 The IFIs’ policies could change (and are arguably in the process of doing so).Footnote 141 In the face of rising material inequality in wealth and income that is exploited by populist and authoritarian leaders, it is no longer sufficient to wait for the developmental benefits of a formal and “thin” rule of law.

International organizations – at least since the 1990s – have insisted on the positive feedback loop (as opposed to antagonism) between economic/social development and constitutionalism/rule of law.Footnote 142 This can be seen from the World Summit Outcome Document of 2005 stating that “rule of law at the national and international levels [is] essential for sustained economic growth, sustainable development and the eradication of poverty and hunger.”Footnote 143 Accordingly, the UN General Assembly Agenda 2030 (adopted in 2015) deals with development but embraces a strong rule-of-law component: “The new Agenda recognizes the need to build peaceful, just and inclusive societies that provide equal access to justice and that are based on respect for human rights (including the right to development), on effective rule of law and good governance at all levels and on transparent, effective and accountable institutions.”Footnote 144

This passage and Sustainable Development Goal 16 advocating for rule of law were controversial and one of the “hotly debated topics” in the process of adopting Agenda 2030.Footnote 145 The outcome has been called a “sea change”Footnote 146 in the area of law and development. Goal 16 seeks to “promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.” More specifically, subgoal 16.3 seeks to “promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all.” A Washington-based think tank has written: “Global declarations and persuasive research demonstrate that there is a connection between the rule of law and sustainable development. Some have questioned both the strength and the causal direction of this connection. But the correlation between a society’s adherence to the rule of law and its progress toward stability and development is beyond question.”Footnote 147

Contrary to what the think-tank wrote, the alleged correlation between the rule of law and economic growth does continue to be questioned.Footnote 148 Skeptics are probably right in asking for incremental improvement of developmental governance capabilities on a small scale (by experimentation and trial and error), taking into full account the political, economic, and institutional conditions in each country.Footnote 149

A different story is that the fixation on economic growth is not sustainable and might need to be complemented or replaced by more ecology- and climate-friendly strategies of development such as “degrowth.” In the end, the economic problems point to the limits of the law as a factor of order, less powerful than economic factors. A moderate capacity to shape reality attaches to the law in general, to constitutional law in particular, and to the rule of law as a principle, too.

VI Conclusions

The current backlash against the “international liberal order” with the rule of law at its coreFootnote 150 must be taken seriously. In this constellation, international organizations’ constitution-shaping requires “[a]n effort for ‘being earnest’” imposing “the need to recognize the political dimension of this agenda and its limits.”Footnote 151 This remark by Valentina Volpe on democracy-promotion applies equally to rule-of-law promotion by international organizations.

It is, at this juncture, not sufficient to point to the fact that the rule-of-law standards used by international organizations as benchmarks derive their legitimacy from state consent and ultimately from state sovereignty. Indeed, the international organizations’ constitutional assistance has not been formally imposed or coerced. However, once a state has decided to take advice, the “national owners” must then comply with the international standards.Footnote 152 This pathway often fuels a sentiment of loss of control that risks backfiring. Therefore, the international organizations’ constitution-shaping activity must pay attention to deeper issues of legitimacy, and must interrogate also the substance and scope of the transnationalized rule of law à fond.

One possible strategy would be to cut back the work of international organizations to the so-called “classic” interstate principles, such as territorial integrity and military security, and leave aside all work on the rule of law (including democracy and human rights). However, this option is not viable, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows. Had the rule of law (including protection of fundamental rights, free elections, and proper dealing with crimes of the past) been guaranteed in Russia, that state would most likely not have engaged in a blatant violation of international law. A transnational rule of law, cutting across the “levels” of governance (entailing both domestic and international law), thus remains a necessary legal principle in order to safeguard international peace and security in their most basic form. For this reason, the constitution-shaping rule-of-law agenda pursued by international organizations should not be abandoned.

However, it needs to be revamped. For the constitution-shaping (and probably all other forms of rule-of-law assistance) to become more legitimate, all international organizations (and their member states) need to avoid the pitfalls of lopsided political human-rightism, abandon double standards, and pursue a much deeper global social agenda. Only then will respect for the rule of law (including access to justice) help with realizing development objectives. Only then will international organizations be able to respond to the current postcolonial sensibility and convince non-Western participants in the transnational ordering process that, indeed, “international law can be transformed into a means by which the marginalized may be empowered” and that “law can play its ideal role in limiting and resisting power.”Footnote 153

I Introduction

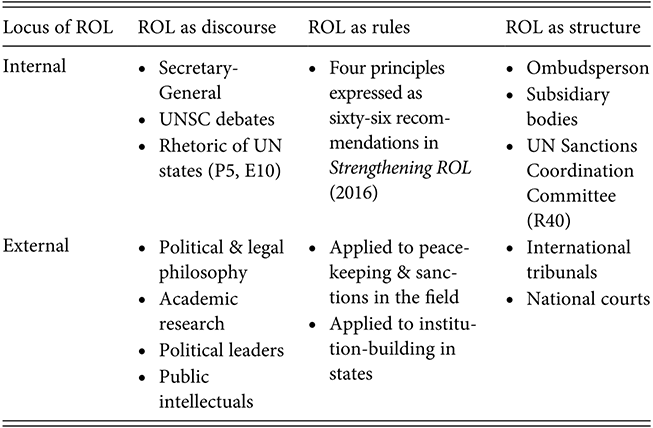

The rule of law is a core concept of modern governance, central to discourses of constitutionalism, good governance, and democracy. It is also increasingly the subject of a transnational discourse, and a “transnational legal order” (TLO) has emerged around the issue, promoting it in national discourse as well as supranational contexts.Footnote 1 The “international rule of law” transposes the idea to the international legal system.Footnote 2 We thus have an ideal, operating at multiple levels of law that interact in complex ways. Enmeshment can take various forms. As regional and international institutions play a greater role in supporting the rule of law on the national plane, the different levels of legal order can be complements to each other toward advancing rule-of-law values. But they might, in some instances, also be institutional substitutes for each other.Footnote 3 This might occur when rule-of-law practices at one level undermine those at another level.

In this chapter we examine efforts to uphold the rule of law by transnational authorities tasked with protecting it. This reflects the general orientation of this collective socio-legal project toward institutional instantiations of the rule of law, rather than pure philosophical definitions.Footnote 4 How, exactly, is the rule of law defended at the international or transnational level, and are these efforts substitutes for or complementary to domestic efforts?

To answer this question, we examine the practices of regional courts and organizations. Regional trade regimes and human rights systems were initially set up with specific goals in mind, for which the rule of law was an implicit requirement but not explicitly stated. Rule-of-law norms crept in through the back door, as it were. But in the past two decades, regional organizations in Africa, Latin America, and Europe have taken on a thicker set of obligations toward protecting the rule of law (along with democracy and other related concepts.) The result is that supranational and international organizations have institutions – courts, commissions, bureaucracies – confronting real-world threats to the rule of law. It is the institutional work that gives actual content to rule-of-law values, and so an appropriate place to look for data on how the concept operates.

The chapter is organized as follows. We briefly sketch definitions. We then briefly survey the use of the rule of the law in the normative architecture and actual case law of major regional organizations, beginning with Latin America, moving to Europe and then Africa. This sequence is determined by the age of the relevant regional system rather than any sense of ontological priority. (We do not devote a separate section to Asia, which is a region notable for its absence of any kind of enforceable framework outside the level of the nation-state. The Charter of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations does mention strengthening the rule of law as part of its object and purpose,Footnote 5 but there has self-consciously been little effort to develop any deeper structure at the regional level.Footnote 6)

We conclude with some reflections on what is learned through the exercise. Courts and other bodies outside the state, in following their own rules, will sometimes find themselves butting up against national-level authorities that are following the dictates of the rule of law according to their own conception, whether or not in good faith. Some tension is to be expected, especially when international regimes are powerful. When one level exercises sufficient power to have an impact on others, it can serve as a substitute or complement in buttressing the rule of law, but interactions can create dynamics that can change the relationship. The region with the least powerful and effective institutions, Africa, is one in which the tensions between the two levels are also absent. This suggests that while harmonious relations across levels of legal order seems intuitively desirable on the surface, such harmony might actually indicate a situation in which the substantive values underpinning the rule of law are too weakly enforced to generate tension.

II The Rule of Law: Trans-, Supra-, Inter-, and National

Definitions of the rule of law are varied, as it is something of an “essentially contested concept.”Footnote 7 Definitions tend to be categorized in relatively thinner, procedural versions and thicker substantive versions. We follow Sandholtz and Shaffer in adopting Krygier’s general conception of the rule of law, whose purpose is to “oppose the ‘arbitrary exercise of power’ by setting boundaries on, and channeling, power’s exercise through known legal rules and institutions that apply to all.”Footnote 8 This ideal can be applied to any exercise of power, including by, most obviously, national-level authorities that must abide by the constitution, but also those authorities operating at the supra- and international levels. We can characterize as international or supranational rule of law the idea that authorities above the level of the nation-state must themselves be bound by rule-of-law principles. National rule of law refers to domestic authority; supranational refers to regional institutions; international to international or global ones.

Complicating this framework is the transnational dimension. The “rule of law revival” of the past two decades has created another phenomenon: a transnational movement to promote the rule of law at the national level.Footnote 9 This movement is best understood as a TLO in Shaffer and Halliday’s terms.Footnote 10 It has normative content, institutional manifestations, and is articulated in a decentralized network that involves actors below, inside, and above the state. Examples include “law and development” work, funded by foreign donors or regional development banks, to build up domestic legal institutions; the World Justice Project’s effort to incentivize improvements through ratings; and transnational movements of judges and lawyers, such as the International Commission of Jurists. These projects seek to bolster and improve the rule of law at the domestic level, playing a complementary role.

Yet another transnational manifestation is the way in which international investment arbitration enforces norms of legality and antiarbitrariness against national authorities. International investment regimes also can require the exhaustion of domestic remedies before seeking international relief. Here, we see the logic of complementarity at first glance: the pressure from outside the country is designed to improve local performance, while deferring in the first instance to national authorities. Of course, the empirical effects are not always so straightforward, and scholars have identified a “substitution effect” from bilateral investment treaties, as they can reduce domestic pressure for reform or provoke backlash.Footnote 11 A transnational rule of law, in this example, might actually undermine domestic rule of law.

When international legal institutions themselves slip from rule-of-law values, supranational or national institutions may be playing the role of buttressing and complementing. For example, in the Kadi line of cases, the European Court of Justice found that fundamental rights in the European Union superseded a Security Council counter-terrorism regime that lacked basic guarantees of due process.Footnote 12

Achieving any vision of the rule of law outside the level of a nation-state requires an institutional architecture. But the design of institutions immediately raises questions of the tension between national-level norms of democracy and the rule of law. The law constrains and orders the will of the demos, and is most necessary when that will is attempting to ride unchecked over minorities. Democracy, as has been suggested elsewhere, requires bureaucracy, in particular an administration that can deliver policies on the basis of politically driven choices, and this bureaucracy must follow principles of legality.Footnote 13 So, the rule of law is built into democracy as a concept.

But the reverse is only partly true. For advocates of a thin, procedural definition of the rule of law, there is no requirement that it be democratically legitimated. Authoritarian states might follow principles of legality and procedural order, which might even constitute “an unqualified human good” in E.P. Thompson’s famous phrase.Footnote 14 Ideals of global administrative law posit a set of stand-alone technocratic principles of legal process that could be applied against international institutions themselves, but also enforced by those institutions against national democratic majorities.Footnote 15 In the former case, the “international” rule of law is a complement to the domestic version; in the latter case, it may be a substitute for it, in the sense that it is most necessary when the domestic version is under threat. But it is also possible that, by undermining the zone of democratic will formation, authorities outside the state can contribute to backlash against the rule of law in its thicker formulation. In short, trans-, supra-, and international institutions can be constitutive of the rule of law, or their antithesis. They can buttress the rule of law at the nation-state level, they can substitute for it, and in some cases their actions will spur backlash against it. For this reason, we are starting to see some scholars concerned with national rule of law and related norms reacting against the transnational rule-of-law complex.Footnote 16

We now turn to several regional institutions to examine their role in protecting the rule of law at the national level – an inquiry especially important in our era of democratic backsliding.

III Latin America and the Caribbean

The Organization of American States has a long history grounded in the protection of democracy in a region in which it has historically been fragile. The normative architecture includes the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, the American Convention on Human Rights, the Inter-American Democratic Charter of 2001, and several other instruments. The primary bodies tasked with implementing these norms are the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Commission) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR).

The rule of law received explicit attention as an overarching goal in the Inter-American Democratic Charter, which identified it as an essential element of representative democracy in multiple articles.Footnote 17 Even before that, however, the jurisprudence of the Commission and IACtHR addressed rule-of-law issues, particularly through the lens of threats to judicial independence. In Castillo Páez v. Peru (judgment on merits of November 2, 1997), the IACtHR defined the content and scope of Article 25 of the Convention, which covers the right to judicial protection. The Court concluded that recourse to courts “is one of the fundamental pillars not only of the American Convention, but of the very rule of law in a democratic society in the terms of the Convention.”Footnote 18 The Court has also focused on Article 23, which is on the right to political participation, but includes the right and opportunity “to have access, under general conditions of equality, to the public service of his country.”Footnote 19 While apparently focused on public employment, the provision has provided a hook for protecting judicial independence, particularly against efforts by leftist Bolivarian governments to pack the courts with their own supporters by dismissing judges appointed by prior regimes.Footnote 20 Because the rule of law requires respect for legal authorities, and because populists tend to view courts as “the most dangerous branch” requiring control, protecting the integrity of courts is a central task for rule-of-law defenders.Footnote 21 This is a good example of a case in which the regional level serves as a backstop and complement to the national level.

There are other cases, however, in which the two levels are in tension. Take, for example, the IACtHR’s doctrine of “conventionality control,” announced in 2006 when it declared that all courts in the member states were obligated to review domestic actions for conformity with the Convention, as interpreted in the jurisprudence of the Court.Footnote 22 Remarkably, this extended to countries in which the domestic constitution did not automatically incorporate international law or give the Convention higher rank. In this sense, the doctrine both advanced regional rule of law (by pushing for uniform application) and undermined domestic rule of law as conceived within autonomous constitutional orders.Footnote 23 This ambitious move led to significant backlash. As Alexandra Huneeus has shown, national courts were leaders in pushing back against the doctrine, raising the issue of exactly whose vision of the rule of law was to be followed.Footnote 24 Substituting for a national process raises significant questions of efficacy and invites backlash, and the IACtHR has tempered its approach in recent years.Footnote 25

Another regional body, the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ), also has confronted the rule of law through the lens of judicial independence. The CCJ has become a kind of regional constitutional court, able to enforce guarantees from national constitutions against the member states. In Bisram v. Department of Public Prosecutions, a Guyanese citizen successfully challenged the procedure used in a murder inquiry.Footnote 26 The Public Prosecutions Act allowed the Director of Public Prosecutions to order a magistrate to reopen an inquiry after an initial finding that no prima facie case had been made. Rather than simply address the procedural errors in the instant case, the CCJ relied on the guarantee of judicial independence in Guyana’s constitution.Footnote 27 Judges at all levels should be free from interference by the executive in their decision-making; the CCJ noted that the constitution “expresses the hallowed, overarching principle of judicial independence, which is described by the Bangalore Principles as a prerequisite to the rule of law and a fundamental guarantee of a fair trial.”Footnote 28

Finally, we can turn to the international rule of law proper, the application of the principles before international institutions. In at least one case, the IACtHR has conceptualized the state as having an obligation to respond to and appear before the Court itself, as a requirement of the international rule of law. The case concerned Trinidad and Tobago, which had a practice of corporal punishment that was alleged to violate the American Convention on Human Rights. An applicant, Winston Caesar, challenged his punishment as well as significant trial delays in the 1990s.

In response to adverse decisions on the death penalty, Trinidad and Tobago had denounced the Convention in 1998, and refused to participate in the proceedings. The IACtHR, however, took the view that the withdrawal did not affect prior cases, for which it had continuing obligations. In a concurrence, Judge Jackman noted:

[Trinidad and Tobago’s] contumelious refusal to acknowledge its continuing obligations under a treaty that remained in force for it when the violations in this case took place represents a gratuitous attack on the Rule of Law, all the more astonishing in a State that, like other Commonwealth Caribbean states, prides itself on its Common Law traditions, where respect for human rights and for the Rule of Law are deeply embedded in the legal culture.Footnote 29

In his separate opinion, Judge Antônio Cançado Trindade criticized Trinidad and Tobago for repeatedly failing to respond to or appear before the Court.Footnote 30 He then discussed the importance of the international rule of law, nonappearance before an international tribunal, and the duty of compliance with its judgment. He noted:

The precedent – among others – set up by the United States, of “withdrawal” and non-appearance before the ICJ, after a Judgment adverse to it on preliminary objections (in 1984) in the Nicaragua versus United States case, would be a very bad example for Trinidad and Tobago to follow. On the occasion, the United States earned much criticism from distinct corners of the international community, including from some of its own most distinguished jurists (like the late Keith Highet), for its disservice to the international rule of law.Footnote 31

This places a duty of good faith appearance at the core of the rule of law, and one that applies to states in their international relations with each other. It is a perfect statement of the demands of the international rule of law, but also illustrates how difficult it is to advance those demands against recalcitrant states.

Together, these IACtHR and CCJ cases focus on several discrete aspects of the rule of law: the duty to provide for independent judicial recourse; the tricky question of impunity; and the duty to comply with commands of international courts, without the possibility of escaping international obligations through denunciation of international instruments. These various discrete applications of the rule of law help us to construct a coherent concept, and to understand the institutional dynamics. In the first, the regional body is a complement or backstop to domestic institutions; in the second, it substitutes for them in its judgment about the rule of law; and in the third, it is implementing a truly international rule of law, directed at the institutions of the regional body itself.

IV Europe

The rule of law is a cornerstone of today’s European legal architecture. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), like its counterpart in the Americas, speaks of related values. Article 2(1) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) cites the rule of law as one of the core values on which the Union is founded. And yet, the rule of law remains one of Europe’s most contentious topics, both politically and legally: Poland (for a period of time) and Hungary built what many describe as “illiberal democracies.” This has led to a series of responses by various European supranational institutions. These responses show the possibility – and the limits – of international institutions in backstopping the rule of law in the face of sustained pressure.

The European experience has been central to articulating a core concept of the rule of law. Ideas related to the rule of law emerged in midcentury as something of an overlapping consensus between ordoliberals, who valued transnational protection of property interests, and social democrats, who were concerned with rights more broadly.Footnote 32

At the same time, the European example illustrates why TLO theory emphasizes the networked nature of the legal concepts on the international plane. It is a story of cooperation among supranational actors with different epistemic bases and institutional structures. They include all European Union institutions, as well as the European Court of Human Rights, which is a traditional interstate human rights court. While their respective understandings may differ at the fringes,Footnote 33 all the European institutions acknowledge a clear core set of principles, including respect for democratic values, human rights, and an independent judiciary, as part of the rule of law.Footnote 34 This understanding emerged as a product of a gradual process that mirrored wider trends: In its early years, the predecessor of what is today the European Union considered itself a trade bloc, without any perceived need or a set of values of its own. But things changed after the Soviet Union fell, when the rule of law became a cornerstone of the legal and political thinking of the time.Footnote 35 Equally, the European Union has evolved beyond being a mere trade bloc.Footnote 36 What it has evolved into (and how it actually protects its values) is less clear. This of course is the underlying question behind many dynamics in today’s rule-of law-discussions.

Finally, the European example shows how difficult it is to operationalize even a robust understanding in light of actual threats to the rule of law. While the European Court of Human Rights has far-reaching powers over the signatory states of the European Convention on Human Rights, it has little leverage to enforce its judgments against a government that is unwilling to abide by its international human rights duties. This is different from the European Union and its institutions, which may be better equipped to handle unwilling member states. But it is much less clear to what extent they can police the member states in areas not expressly governed by the European treaties. European Union involvement therefore adds another layer of complexity when evaluating the supranational response to rule-of-law backsliding: Conflicts about the rule of law are now also domestic constitutional conflicts. They touch on the very nature of the European project.

1 Developing Core Rule-of-Law Principles through the European Courts

On the EU level, rule-of-law thinking is usually traced to Les Verts, a 1987 judgment of the European Court of Justice.Footnote 37 The Court explained that the European Community (as it was known as the time) is “based on the rule of law inasmuch as neither its member states nor its institutions can avoid a review of the question whether the measures adopted by them are in conformity with the basic constitutional charter, the Treaty.” This implicates what we have called the supranational rule of law.

Even earlier, the Court of Justice had established the principle of legal certainty and protections against retroactive laws in what is now European Union law.Footnote 38 In addition, it recognized the principle of legality – that is, the requirement that rules are set in a transparent, accountable, democratic, and pluralistic process: “In a community governed by the rule of law”, the Court said, “adherence to legality must be properly ensured.”Footnote 39 Similar ideas were to be found in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights.Footnote 40 One by one, the European Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights acknowledged the principles that constitute the rule of law. When the European institutions developed today’s more comprehensive definitions, they only had to aggregate the courts’ jurisprudence on those building blocks.Footnote 41

In 1989, for example, the European Court of Justice acknowledged that in all member states any government intervention needs to have a legal basis and needs to be justified on grounds laid down by law:Footnote 42 “The need for such protection must be recognized as a general principle of [what is today European Union] law.” This prohibits the arbitrary use of government powers. In keeping with TLO theory’s emphasis on the networked nature of the legal concepts on the international plane, the Court’s argument mirrored the preamble of the ECHR, which refers to the rule of law as part of the “common heritage” of its signatory states. This is, of course, strikingly different from today’s rule-of-law discussions: In this early stage, the rule of law was enshrined in national (constitutional) law and then “borrowed” by the supranational level. The idea that supranational, European rule-of-law principles may need to be enforced against a nation-state seemed far-fetched at the time.

Nonetheless, at this early stage the European courts also dealt with what would become today’s main battleground: judicial independence. In a Union based on the rule of law, the European Court of Justice ruled, effective judicial review, including respect for fundamental rights, is of central importance.Footnote 43 The right to effective judicial protection is again described as “one of the general principles of law stemming from the constitutional traditions common to the Member States.”Footnote 44 The Court links this idea then to the ECHR and its protection of a fair trial in Article 6 – and to the right to an independent tribunal thereunder.Footnote 45 This is yet another example of how the two supranational European courts acted in concert to erect today’s rule-of-law edifice.

2 Entrenching and Defining the Rule of Law in Treaty Texts and through Reports by Supranational Institutions

By the beginning of the 1990s, the European courts had spelled out most of the core principles that fall within the broader concept of the rule of law. While the Council of Europe institutions, in both the Convention preamble and Article 3 of the Statute of the Council of Europe, specifically mention the rule of law, European Community documents did not do so until 1992.Footnote 46 But very much in line with a greater focus on democracy and human rights, this marked the beginning of a legal order in which the rule of law is deeply enshrined in all treaty texts. Not only is it a value on which the Union is founded (see Article 2(1) TEU). Respect for and the willingness to promote the rule of law are required to apply for membership in the European Union under Article 49(1) TEU. Also, in its external relations, under Article 21(1) and (2) TEU, rule-of-law considerations are paramount. But one crucial element continued to be missing: No text offered a clear definition of what is meant by the rule of law, let alone one that is actionable in court. Developing such a definition fell to Europe’s supranational institutions.