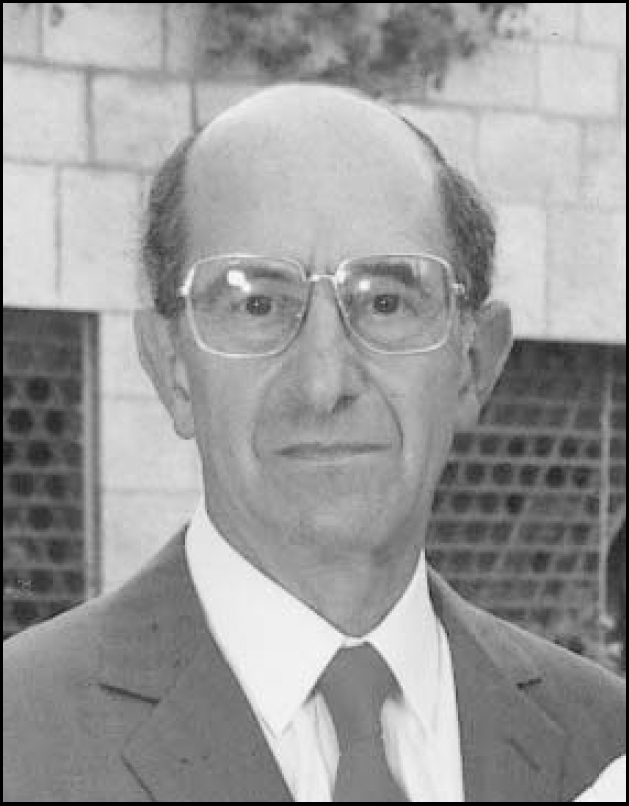

Samuel (Sam, as he was popularly known) Cohen was Professor of Psychiatry at the Royal London Hospital from 1984 to 1990, but he had been on the clinical staff of the hospital from 1961.

He was born in 1925 in South Wales, and studied medicine in Cardiff. He won the Gold medal in anatomy, and after taking a degree in physiology he qualified MB BCh in 1948. He gained the MD (Lond) in 1953 and was elected FRCP (Eng.) in 1994. After house jobs in Cardiff, he took further training in medicine at the Hammersmith and at the Brompton Chest Hospitals in London, before returning to Cardiff as a lecturer on the medical unit. He had contracted tuberculosis as a medical student and his career was interrupted in 1950 by a flare-up of pulmonary tuberculosis, for which he was hospitalised at Frimley Hospital, and underwent therapeutic pneumothorax.

He began psychiatry in 1956 at the Maudsley Hospital during the era of Professor Sir Aubrey Lewis and obtained the DPM in 1958. He was elected to the Foundation Fellowship of the Royal College of Psychiatrists in 1971. He developed a particular interest in psychosomatic disorders and in the pathophysiology underlying somatic symptoms. He was one of the first psychiatrists on the staff of the London Hospital who worked in Whitechapel, and helped to incorporate and develop the site at St Clement's in Bow when it became part of the London Hospital.

He was in the forefront of developments in what became known as liaison psychiatry. His greatest administrative achievement, however, was to persuade ten surgeons and physicians at the Royal London Hospital to surrender two beds each, in order to open Rachel as a psychiatric ward within the general teaching hospital. There he fostered liaison psychiatry as well as playing his part in the catchment area service for psychiatry in the Tower Hamlets district of East London. He encouraged psychotherapeutic approaches alongside physical treatments, and Rachel ward was in many ways a therapeutic community.

He was invited to Israel in 1968 and devoted a year to moving and reestablishing the Ezrath Nashim Hospital in Jerusalem as a modern psychiatric centre. He was opposed to policies of ‘seclusion’ of disturbed patients and was proud to remove restraints that had been commonly used on patients. The hospital, later renamed the Herzog Hospital, became internationally renowned for psychiatric research.

As a clinician, he was especially gifted at helping people with complex psychosomatic problems, which had baffled a succession of other specialists. He was always on the lookout for problems arising from marital difficulties, from misuse of alcohol, tranquillisers or cannabis, as well as alert to those symptoms arising from the abrupt discontinuation of prescribed drugs or alcohol. As a teacher, Sam was respected for his attention to detail, his thoroughness in gathering and understanding the patient's history and summarising it as a formulation. As chairman of the department of psychiatry from the late 1970s, he assembled an outstanding group of clinicians. He was keen to integrate the psychiatric departments of the London and St Bartholomew's Hospitals, an inevitable process, which initially met with much resistance. He was an impressive committee chairman, not least for his sense of time. He was known for his integrity, warmth, and loyalty. His respect among senior medical staff of all disciplines was recognised by his election as Chairman of the Medical Council of the Royal London Hospital, in which capacity he threw his weight into operating the helicopter emergency service. Furthermore, he supported Professor Wendy Savage at a time when community obstetrics faced daunting accusations; his sympathy, warmth and calm persistence were invaluable.

Sam was strengthened by the support of his marriage to Vivienne. Their meeting in 1948, at a hotel in Eastbourne, while Vivienne was still a medical student had been engineered by his grandmother; they married in 1955.

He enjoyed hill walking in Scotland and travelled widely. He maintained a youthful, down-to-earth quality and a sense of humour, well suited to working with the serious mental health problems in London's East End. He was a good listener and made people feel valued and interesting.

His lasting legacy lies in the trainees who joined the rotation to work with him, who later themselves became famed for liaison and other branches of psychiatry.

After retirement Sam continued to do clinical work as a visiting professor, for a few months each year until 1998, in Australia and New Zealand. Sam was a scholar, for example, he continued to study and publish papers concerning the Book of Psalms and their structure.

He had suffered from lymphatic leukaemia for several years, but his health deteriorated while in St Petersburg in 2003. During chemotherapy, he suffered a series of infections, including a recurrence of the tuberculosis from his youth; he was nursed at home in London until his death on 9 September 2004.

Sam was devoted to his family and is survived by Vivienne, their son and daughter, twelve adoring grandchildren, and one great grandchild.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.