Telugu (tel) belongs to the Dravidian family of languages and is spoken by 7.19% of the population of IndiaFootnote 1 (Census of India 2001b). At different stages of its development over centuries, the vocabulary of Telugu has been considerably influenced by various languages, such as Sanskrit, Prakrit,Footnote 2 Perso-Arabic and English. A major consequence of this influence is that the phonemic system of Telugu has been extended by additional sets of sounds. Thus, the aspirates /pʰ bʱ tʰ dʱ ʈʰ ɖʱ ʧʰ ʤʱ kʰ ɡʱ/ and fricatives /ʃ ʂ h/, absent in the native phonemic system, entered the language through Sanskrit borrowings. Similarly, /f/ entered the language through Perso-Arabic and English borrowings. Some of the sounds from Perso-Arabic and English sources were nativized, for example, Perso-Arabic and English phoneme /ʃ/ was rendered as /ʂ/, which had already entered the language through borrowings from Sanskrit/Prakrit; Perso-Arabic phonemes /q x ɣ z/ were rendered as /k kʰ ɡ ʤ/ respectively; and the English phoneme /θ/ was rendered as /tʰ/. English borrowings also resulted in re-phonemicization. In native Telugu vocabulary, [ɛ] and [ӕː] are allophones of /e/ and /eː/ respectively, but they acquire phonemic status when words borrowed from English are included in the total vocabulary of the language.

This extended phonemic system came to be reflected in the formal speech style of well-educated people, while the native phonemic system, devoid of the additional phonemes, is reflected in the speech of the uneducated (Krishnamurti & Gwynn Reference Krishnamurti and Gwynn1985). Sjoberg (Reference Sjoberg1962) observes that while the educated speakers (of the ‘East Godavari dialect’) use the full set of the extended phonemic system in formal domains like ‘public lectures, over the radio, in worship, occasionally by professors in classroom’ Sjoberg (Reference Sjoberg1962: 270); in informal domains like ‘at home, in conversation with friends, relatives and inferiors’ they make use of a rather smaller set which exclude some aspirate sounds like /pʰ ʧʰ ʤʱ kʰ ɡʱ/, thereby establishing the ‘coexistence of two distinctive phonemic systems’ Sjoberg (Reference Sjoberg1962: 269).

From the above sources (Sjoberg Reference Sjoberg1962, Krishnamurti & Gwynn Reference Krishnamurti and Gwynn1985) it can be deduced that the formal speech of educated speakers would provide the maximal inventory of phonemes of the language. Hence, the present analysis is based on the phonemic system as reflected in the formal speech of an educated Telugu speaker from the eastern dialect area,Footnote 3 specifically from the Vizianagaram area.

Consonants

An explanation of two of the above places of articulation is necessary. The stricture for dentialveolars is formed by laminal contact across the alveolar region and touching the base of the upper front teeth. In the case of palato-alveolars, the closure stricture is formed over a wide area comprising the postalveolar region, whereas for the palatal approximant, the stricture is palatal.

Phonotactics of consonants

Aspirates are available mostly in Tatsama (Sanskrit borrowings) and Tadbhava (Prakrits borrowings) words. In addition, /tʰ/ as a reflex of source /θ/ is available in words borrowed from English, as in the case of Eng. /θɪn/ ‘thin’ > Tel. /tʰi n n u/. The only aspirated plosive that is found in native words is /dʱ/ which is limited to just a couple of compound numeralsFootnote 5 in careful speech, e.g. /pɐd dʱe n i m i d i/ ‘eighteen’ and /pɐdʱnɐːl uɡu/ ‘fourteen’. Of the other aspirates, /ʈʰ ɖʱ ʤʱ/ occur very rarely.Footnote 6 A majority of the occurrences of /dʱ/ are reflexes of the source /tʰ/ in Tatsama words e.g. Skt. /pɑn tʰ/ ‘to travel’ is realized as /pɐn dʱɐː/ ‘method’ in Telugu. This change is reflected in writing as well (except by those who are well-versed in Sanskrit) and it often makes it difficult to recover the original /tʰ/ in words like /ɐr dʱɐ/ ‘meaning’ (< Skt. /ɑr tʰɑ/) as opposed to /ɐr dʱɐ/ ‘half’ (= Skt. /ɑr dʱɑ/). Source /tʰ/ is retained when it occurs as the second member of a cluster beginning with /s/, as in /s tʰɐlɐm/ ‘place’ and /p rɐs tʰɐːnɐm/ ‘departure’.

Among the fricatives, /f/, /ʃ/, and /ʂ/ are available only in borrowed vocabulary e.g. /kɐːf iː/ ‘coffee’, /fɐlɐːnɐː/ ‘particular’; /ʃɐk t i/ ‘energy’, /ɐːʃɐ/ ‘desire’; /kɐːʂɐːj i/ ‘ochre-coloured’. In addition, Tatsama source /pʰ/ is often realized as /f/ in ‘anglicized’ pronunciation, e.g. Skt. /pʰɑl i tɑm/ ‘result’ > Tel. /fɐl i tɐm/.

A few native words such as /hɐːj i/ ‘pleasantness’ and interjections /ɐːhɐː/ ‘expressing appreciation’, /oːh oː/ ‘expressing surprise’ contain /h/. All the other words having the phoneme /h/ are borrowed. Of the affricates, /ʦ/ and /ʣ/ are available only in native words. Since only the native vocabulary allows these two affricates, their aspirated counterparts are not available in the language as aspiration is essentially a feature found in borrowed vocabulary.

Among the retroflexes, /ɳ/ and /ɭ/ do not occur word-initially. They occur in intervocalic position and when adjacent to a retroflex consonant, e.g. /ʋɐːɳiː/ ‘tippet’, /kɐʈɳɐm/ ‘dowry’, /pɐɳɖu/ ‘fruit’; /kɐɭɐ/ ‘art’, /bɐːɭʈi/ ‘bucket’.

However, the rest of the retroflex sounds are attested in word-initial position in a few words, e.g. /ʈɐk k u/ ‘pretence’, /ʈʰiːʋi/ ‘grandeur’, /ɖi p pɐ/ ‘half of a spherical object’, /ɖʱoːkɐː/ ‘danger’, /ʂoːk u/ ‘fashionable appearance’.

/j/ occurs in word-initial position only in borrowed words, e.g. /jɐnɡu/ < Eng.‘young’, /jɐʃɐs s u/ < Skt. /jɑʃɑs/ ‘fame’.

Consonant clusters are more common in borrowed than in native vocabulary. In borrowed vocabulary, most of the consonant clusters of the source language are retained in formal educated speech. The fricatives /f ʂ ʃ h/ and the nasal /ɳ/ do not contrast for gemination. Contrast for gemination is limited to words of the syllabic structure #(C₁)VC₂V. . ., where C₁ is optional and C₂ contrasts for gemination. A few examples include /ɡɐd

i/ ‘room’ – /ɡɐd

d

i/ ‘throne’, /ɐʈu/ ‘that side’ – /ɐʈʈu/ ‘pancake’, /m

oɡɐ/ ‘male’ – /m

oɡɡɐ/ ‘bud’, /nɐmɐkɐm/ ‘a vedic hymn’ – /nɐm

mɐkɐm/ ‘belief’, /kɐn

u/ ‘to give birth to’ – /kɐn

n

u/ ‘eye’, /kɐlɐ/ ‘dream’ – /kɐl

lɐ/ ‘falsehood’, /mɐr

i/ ‘again’ – /mɐr

r

i/ ‘banyan tree’. In geminated plosives (including affricates), the first component has no audible release and as a result, in that position, aspiration and affrication are not realized since these two features are dependent upon release; for example, /kʰkʰɐ/ is realized as [k

![]() kʰɐ] and /ʤʤi/ is realized as [ɟ

kʰɐ] and /ʤʤi/ is realized as [ɟ

![]() ʤi] and /ʣʣɐ/ as [d

ʤi] and /ʣʣɐ/ as [d

![]() ʣɐ]. A few native words have intra-word consonant sequences, e.g. /ɐːs

t

i/ ‘wealth’, /kɐːs

tɐ/ ‘a little’, /ɡu

r

t

u/ ‘mark’. Several derived verbal bases contain consonant sequences formed by the addition of the causative suffix /ʦu/, e.g. /p

eːlʦu/ ‘to burst (something)’, /d

i

nʦu/ ‘to bring down’. A syllable boundary separates all these consonant sequences. Similarly, as detailed in Bhaskararao (Reference Bhaskararao1982), within the native vocabulary, several consonantal clusters arise out of extensive morphophonemic processes such as short vowel deletion and consonant assimilation, e.g. /ʋɐːɳɭoːpɐl

i

k

i

p

i

lʧeːn

u/ (<ʋɐːɖi-ni loːpɐlɐ-ki pili-ʧeː-nu) ‘I called him in’.

ʣɐ]. A few native words have intra-word consonant sequences, e.g. /ɐːs

t

i/ ‘wealth’, /kɐːs

tɐ/ ‘a little’, /ɡu

r

t

u/ ‘mark’. Several derived verbal bases contain consonant sequences formed by the addition of the causative suffix /ʦu/, e.g. /p

eːlʦu/ ‘to burst (something)’, /d

i

nʦu/ ‘to bring down’. A syllable boundary separates all these consonant sequences. Similarly, as detailed in Bhaskararao (Reference Bhaskararao1982), within the native vocabulary, several consonantal clusters arise out of extensive morphophonemic processes such as short vowel deletion and consonant assimilation, e.g. /ʋɐːɳɭoːpɐl

i

k

i

p

i

lʧeːn

u/ (<ʋɐːɖi-ni loːpɐlɐ-ki pili-ʧeː-nu) ‘I called him in’.

The only consonants that can occur word-finally in the native vocabulary are /m/ and /j/. Otherwise words in native vocabulary end in vowels. /j/ occurs word-finally in non-polite imperative verbs, e.g. /k

o

j/ ‘(you sg) cut it!’, /ʧe

j/ ‘(you sg) do it!’. In emphasized or careful speech these two words may be rendered as /k

o

j

j

i/, /ʧe

j

j

i/ respectively. As explained later, /m/ is phonetically [

![]() ] in word-final position. It is interesting to note that the phonetic representation of both /j/ and /m/ (i.e. [j] and [

] in word-final position. It is interesting to note that the phonetic representation of both /j/ and /m/ (i.e. [j] and [

![]() ]) are basically vocoids. Hence, one can generalize that at phonetic level all native words in Telugu end in vocoids.

]) are basically vocoids. Hence, one can generalize that at phonetic level all native words in Telugu end in vocoids.

Allophones of consonants

Phonetic realization of /m/ as [m] and [

![]() ] has been noted by Lisker (Reference Lisker1963: 6), Bhaskararao (Reference Bhaskararao1972: 76), Subrahmanyam (Reference Subrahmanyam1974: 12), and Krishnamurti & Gwynn (Reference Krishnamurti and Gwynn1985: 9). /m/ is realized as [

] has been noted by Lisker (Reference Lisker1963: 6), Bhaskararao (Reference Bhaskararao1972: 76), Subrahmanyam (Reference Subrahmanyam1974: 12), and Krishnamurti & Gwynn (Reference Krishnamurti and Gwynn1985: 9). /m/ is realized as [

![]() ] or [m]. In intervocalic position, both the realizations vary freely, e.g. [ʧɪː

] or [m]. In intervocalic position, both the realizations vary freely, e.g. [ʧɪː

![]() ɐ] ‘ant’, [ʋɐːm

i] ‘haystack’. In word-final position, its preferred realization is [

ɐ] ‘ant’, [ʋɐːm

i] ‘haystack’. In word-final position, its preferred realization is [

![]() ], e.g. [pɔlɐ

], e.g. [pɔlɐ

![]() ] ‘agricultural field’. In addition, [

] ‘agricultural field’. In addition, [

![]() ] is the preferred pronunciation of /m/ when it occurs before the consonants /r

f

s ʃ h

l ʋ/: [sɑ

] is the preferred pronunciation of /m/ when it occurs before the consonants /r

f

s ʃ h

l ʋ/: [sɑ

![]() ɾɑkʂɑɳɐ

ɾɑkʂɑɳɐ

![]() ] ‘protection’, [pӕː

] ‘protection’, [pӕː

![]() f

l

eʈʈu] ‘pamphlet’, [mɑː

f

l

eʈʈu] ‘pamphlet’, [mɑː

![]() sɐ

sɐ

![]() ] ‘meat’, [ʋɑ

] ‘meat’, [ʋɑ

![]() ʃɐ

ʃɐ

![]() ] ‘lineage’, [sɪ

] ‘lineage’, [sɪ

![]() hɐ

hɐ

![]() ] ‘lion’, [sɑ

] ‘lion’, [sɑ

![]() lɑɡnɐ] ‘well-joined’, [sɑ

lɑɡnɐ] ‘well-joined’, [sɑ

![]()

![]() ɑt

sɑɾɐ

ɑt

sɑɾɐ

![]() ] ‘year’ (</sɐmʋɐt

sɐɾɐ

] ‘year’ (</sɐmʋɐt

sɐɾɐ

![]() /). /m/ is realized as [

/). /m/ is realized as [

![]() ] before /j/ in words like [sɐ

] before /j/ in words like [sɐ

![]()

![]() ɔːɡɐ

ɔːɡɐ

![]() ] ‘combination’(</sɐm

j

oːɡɐm/).Footnote

7

] ‘combination’(</sɐm

j

oːɡɐm/).Footnote

7

Elsewhere /m/ is realized as [m], e.g. [mɑːʈɐ] ‘word’, [ɑm mɐ] ‘mother’, [ɡu m p u] ‘crowd’, [ɑːt mɐ] ‘soul’, [kɐmʧiː] ‘whip’, [ʧɐm k iː] ‘glittering embroidery’, [ʧɪmʈɐː] ‘tongs’, [ʧɑmɽɐː] ‘leather’.

/n/ has a palatal allophone [ɲ] when it is adjacent to a palato-alveolar consonant, a velar allophone [ŋ] before a velar consonant and a dental allophone [n] elsewhere: [sɐɲʧiː] ‘bag’, [mʊɲʤɐ] ‘tender jelly like kernel of palm fruit’, [ɑːʤɲɐ] ‘command’; [ɐŋk

e] ‘number’, [rɐŋɡu] ‘colour’; [ɑn

dɐ

![]() ] ‘beauty’, [n

i

p

p

u] ‘fire’, [n

eːn

u] ‘I’, [kɐn

n

u] ‘eye’.

] ‘beauty’, [n

i

p

p

u] ‘fire’, [n

eːn

u] ‘I’, [kɐn

n

u] ‘eye’.

In intervocalic position the pronunciation of singleton /ɳ/ i

s

t

h

a

t

o

f

a

f

l

a

p, e.g. [ʋɐː

![]() iː] ‘tippet’. Intervocalic singleton /ɖ/, /ɖʱ/ and /ɭ/ also have flap pronunciation, e.g. [ʋɐːɽu] ‘he’, [m

uːɽʱuɽu] ‘foolish man’, [tɑː

iː] ‘tippet’. Intervocalic singleton /ɖ/, /ɖʱ/ and /ɭ/ also have flap pronunciation, e.g. [ʋɐːɽu] ‘he’, [m

uːɽʱuɽu] ‘foolish man’, [tɑː

![]() ɐ

ɐ

![]() ] ‘lock’.Footnote

8

/ɖ/ occurs after the nasal /m/ in a few borrowed words, where it is realized as a flap, e.g. [ʧɑmɽɐː] ‘leather’.

] ‘lock’.Footnote

8

/ɖ/ occurs after the nasal /m/ in a few borrowed words, where it is realized as a flap, e.g. [ʧɑmɽɐː] ‘leather’.

/r/ has two allophones, tap [ɾ] in intervocalic position and trill [r] elsewhere e.g. [p eːɾu] ‘name’, [r eːp u] ‘tomorrow’, [kɑr rɐ] ‘stick’.

If only native vocabulary is considered, [ʦ] and [ʧ] stand as allophones of /ʦ/, and [ʣ] and [ʤ] as allophones of /ʣ/. While [ʧ] and [ʤ] occur before front vowels, [ʦ] and [ʣ] occur before non-front vowels. However the influx of Tatsama words brought [ʦ] and [ʣ] (in native words) into phonemic contrast with [ʧ] and [ʤ] (in Tatsama words) respectively (Sjoberg Reference Sjoberg1962), as is evident in pairs like /ʦɐːpɐ/ ‘mat’ – /ʧɐːpɐm/ ‘bow’ and /ʣɐːɾu/ ‘sharpness’ – /ʤɐːt i/ ‘race’.

Each of the voiced phonemes /ʤ/ and /ʣ/ have a fricative allophone and an affricate allophone. Their distribution is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Distribution of the allophones of /ʤ/ and /ʣ/.

The phonetic realizations of /ʋ/ are [ʋ] and [w], which freely vary in many contexts. However, [w] is the preferred realization when it is adjacent to a rounded vowel. It should be pointed out that this allophone, [w], may not possess the velar approximation to qualify to be an archetypical ‘labial-velar approximant’ but may be rendered as [

![]() ], a ‘voiced bilabial approximant’.

], a ‘voiced bilabial approximant’.

/ʋ/ is realized as [

![]() ] when it is preceded by the allophone [

] when it is preceded by the allophone [

![]() ] of /m/, e.g. /sɐmʋɐt

sɐrɐm/ > [sɑ

] of /m/, e.g. /sɐmʋɐt

sɐrɐm/ > [sɑ

![]()

![]() ɑt

sɑɾɐ

ɑt

sɑɾɐ

![]() ] ‘year’. Similarly, /j/ is realized as [

] ‘year’. Similarly, /j/ is realized as [

![]() ] when preceded by the allophone [

] when preceded by the allophone [

![]() ] of /m/, e.g. /sɐm

j

oːɡɐm/ > [sɐ

] of /m/, e.g. /sɐm

j

oːɡɐm/ > [sɐ

![]()

![]() ɔːɡɐ

ɔːɡɐ

![]() ] ‘combination’.

] ‘combination’.

Vowels

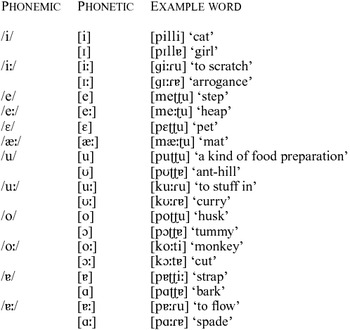

Figure 1 enumerates the vowels of Telugu pronounced in isolation by a single speaker. All the vowel phonemes except /ɛ/ and /æː/ contrast for length.

Figure 1 Vowels pronounced in isolation.

Phonotactics of vowels

All short vowels occur in all positions of a word, with the exception of /o/, which does not occur word-finally. Native lexical items do not end in a long vowel. However, native words ending in certain particles (that are represented solely by a long vowel) contain long vowels in the final position. The long vowel of the particles in turn causes elision of the original final short vowel of the base, e.g. /ɐdӕː/ ‘is that?’ (</ɐd i/ ‘this’+/ɐː/ ‘interrogative particle’), /ɐd oː/ ‘possibly it’ (</ɐd i/ ‘this’+/oː/ ‘dubitative particle’), /ɐd eː/ ‘it only’ (</ɐd i/ ‘this’+/eː/ ‘emphatic particle’).

Some borrowed words can contain word-final long vowels. These long vowels are optionally but preferably replaced by their short counterparts when the word is pronounced in isolation. However, the underlying final long vowel is recalled in pronunciation when the word is inflected by the addition of a suffix, e.g. /ʋɐːʧiː/ ~ /ʋɐːʧi/ ‘wrist watch’ but /ʋɐːʧiːl u/, not /ʋɐːʧi l u/ for ‘wrist watches’. Had the underlying form been /ʋɐːʧi/, with a short final vowel, its plural would have wrongly become /ʋɐːʦu l u/ by the application of a morphophonemic rule which converts final short /i/ to /u/ before the plural suffix /l u/. Similarly, /h iːr oː/ ~ /h iːr o/ ‘hero’ – /h iːr oːl u/ ‘heroes’ (not /h iːr o l u/).

An underlying final /e/ of a word preferably alternates with /i/ when it is pronounced in isolation. However, when the word is inflected with certain suffixes, the underlying /e/ is recalled, e.g. /ɐd d e/ ~ /ɐd d i/ ‘rent’ – /ɐd d e l u/ ‘rents’ but not /ɐd d i l u/. If the /ɐd d i l u/ option is chosen, then it would have to undergo a further process of vowel harmony, where the /u/ of the plural suffix /l u/ would have converted the final /i/ of the noun to /u/, wrongly resulting in /ɐd d u l u/. Similarly /sɐːr e/ ~ /sɐːr i/ ‘post-wedding gift’ – /sɐːr e l u/ ‘post-wedding gifts’ (compare /sɐːr i/ ‘an instance’ – /sɐːr u l u/ ‘instances’).

Allophones of vowels

The vowel of a syllable is lowered when followed by a syllable with the low vowel /ɐ/ or /ɐː/ (Subrahmanyam Reference Subrahmanyam1974; see Figure 2). Thus, /ɛ/ and /æː/ are allophones of /e/ and /eː/ respectively in native vocabulary (e.g. [p eʈʈi] ‘box’ vs. [pɛʈʈɐ] ‘hen’, [p eːɽu] ‘wood splinter’ vs. [pӕːɽɐ] ‘cattle dung’), but these pairs stand in contrast when considering borrowed vocabulary together with native vocabulary (e.g. [sɛɳɖu] ‘to send’ vs. [sӕːɳɖu] ‘sand’). Thus, when both the native and borrowed vocabularies are combined (as in the speech of educated speakers) we find all the four sounds, /e eː ɛ æː/ in contrastive distribution e.g. /b eɳɖu/ ‘cork’ – /bɛɳɖu/ ‘bend’ (<Eng.) – /bæːɳɖu/ ‘band’ (<Eng.) and /m eːʈu/ ‘heap’ – /mæːʈu/ ‘mat’ (<Eng.).

Figure 2 Vowel allophones.

Vowel allophones are illustrated by the following examples:

Post-sandhi changes in vowels and consonants

Telugu uses extensive sandhi processes involving both consonants and vowels at morpheme junctures (Krishnamurti Reference Krishnamurti1957, Kelley Reference Kelley1959, Lisker Reference Lisker1963, Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson1974, Bhaskararao Reference Bhaskararao1982). Several of the sandhi processes can be both internal and external (Kelley Reference Kelley1963), as illustrated in Table 2. Steps 1A–G illustrate application of sandhi changes word-internally and 2A–D illustrate sandhi changes applied word-externally. It may be noted that ‘short vowel elision between homorganic consonants’ and ‘regressive consonant assimilation’ can be applied both word-internally and word-externally.

Table 2 Examples of internal and external sandhi processes.

As explained earlier, an /ɐ/ or /ɐː/ lowers a vowel in the preceding syllable. This process is applicable only within a word which could be either uninflected or inflected. In other words, the controlling vowel /ɐ/ or / ɐː/ is either present inherently in the lexical form of the word or occupies the appropriate controlling position as a result of internal sandhi processes.

Table 3 gives examples of this phenomenon (for abbreviations and notation see the list at the end of the Illustration). In the case of the example for internal sandhi (traced through steps 1A–E), in the formation of ‘negative imperative form of a verb’ given in column II, vowel /ɐ/ which originally belongs to the inflectional suffix /ɐk u/ occupies the V₂ position and lowers the [o] in the preceding syllable to [ɔ]. In the formation of a ‘past participle’ of a verb, vowel /i/ of the inflectional suffix occupies the V₂ position and since it has no lowering effect on V₁, the V₁ retains its original height.

Table 3 Comparison of operation of internal sandhi and external sandhi in identical environments.

In the case of the example for external sandhi (traced through steps 2A–C), in the forms given in column II, although vowel /ɐ/ which originally belongs to the following word, now occupies the V₂ position, it does not lower the V₁ of the preceding word. Thus, the scope of lowering effect of /ɐ/ is word-internal but not word-external.

If, after a word-internal process is completed, there arises a word-external condition that has the potential to influence the word-internal condition, then this potential influence is nullified. This is illustrated in Table 4. In B2, vowel /ɐ/, which is in the V₂ position, lowers /o/ to [ɔ] in the V₁ position whereas in B1, the V₁ /o/ is not lowered since it is not followed by /ɐ/ in V₂ position. This is a word-internal process. Column C contains forms juxtaposed for the operation of a word-external process of vowel deletion by which the original V₂ of the word is replaced by /ɐ/ (of the word /ɐd i/). Forms in column D include the forms after the external sandhi process is completed. The final output of the process results in a condition where the earlier allophonic variants [o] (in [p oʈʈu] ‘husk’) and [ɔ] (in [pɔʈʈɐ] ‘tummy’) now stand in contrast in [p oʈʈɐd i] ‘It is husk’ and [pɔʈʈɐd i] ‘It is a tummy’.

Table 4 Examples of external sandhi changes not influencing word-internal phonetic realization.

Among consonants, as noted earlier, the phoneme /m/ has the allophones [m] and [

![]() ], and the phoneme /ʋ/ has the allophone [ʋ]. However, in the case of some inflected verbal paradigms, in their post-sandhi forms, the allophones of /m/ as well as the allophone of /ʋ/ emerge in contrastive distribution (Lisker Reference Lisker1963), as shown in Table 5.

], and the phoneme /ʋ/ has the allophone [ʋ]. However, in the case of some inflected verbal paradigms, in their post-sandhi forms, the allophones of /m/ as well as the allophone of /ʋ/ emerge in contrastive distribution (Lisker Reference Lisker1963), as shown in Table 5.

Table 5 Forms illustrating post-sandhi changes in consonants.

The underlying string for Form1 is /k

oʈʈu

m

u ɐn

nɐːn

u/ ‘Hit (imperative singular) – I said’. In this form, the /k

oʈʈu

m

u/ portion, meaning ‘hit (imperative singular)’, is available only in literary Telugu and is preserved in such constructions in contemporary language. But speakers of contemporary colloquial Telugu do not have access to this historical information. Its contemporary reflex is /k

oʈʈu/ ‘hit! (verb_root)’. After the ‘short vowel deletion’ and ‘vowel copying’ rules are applied, the resulting form would be /k

oʈʈɐmɐn

nɐːn

u/. This form is morphologically reanalysedFootnote

9

in contemporary Telugu as /k

oʈʈɐ-mɐn

nɐːn

u/. Now /k

oʈʈɐ/ is reanalysed as /k

oʈʈu-ɐ/, where /ɐ/ is treated as an infinitive suffix. This enables /ɐ/ to cause the V₁ /o/ to be realized as [ɔ]. Further, /m/ now occupies initial position of the remnant /mɐn

nɐːn

u/ and hence gets realized as [m] but not as [

![]() ].

].

Suprasegmentals

Telugu does not have lexically contrastive stress or pitch. However, pitch changes are used in forming intonation patterns.

Transcription of recorded passage: ‘The North Wind and the Sun’

Phonemic transcription

Orthographic rendering

Abbreviations and notation

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Kishore Prahallad and S. Rajendran for their helpful suggestions of the initial versions of the paper. The meticulous criticism and comments by the two anonymous reviewers and by the editor of the Journal, Adrian Simpson, are appreciated. We are thankful to K. Sudarshan and P. Gangamohan for their help with signal processing issues.